Abstract

Objectives

To investigate how many general practitioner (GP)-referred venous thromboembolic events (VTEs) are diagnosed during 1 year in one geographical region and to investigate the (urgent) referral pathway of VTE diagnoses, including the role of laboratory D-dimer testing.

Design

Historical cohort study.

Setting

GP patients of 47 general practices in a demarcated geographical region of 161 503 inhabitants in the Netherlands.

Participants

We analysed all 895 primary care patients in whom either the GP determined a D-dimer value or who had a diagnostic work-up for suspected VTE in a non-academic hospital during 2015.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcomes of this study were the total number of VTEs per year and the diagnostic pathways—including the role of GP determined D-dimer testing—of patients urgently referred to secondary care for suspected VTE. Additionally, we explored the use of an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off.

Results

The annual VTE incidence was 0.9 per 1000 inhabitants. GPs annually ordered 5.1 D-dimer tests per 1000 inhabitants. Of 470 urgently GP-referred patients, 31.3% had a VTE. Of those urgently referred based on clinical assessment only (without D-dimer testing), 73.8% (96/130) had a VTE; based on clinical assessment and laboratory D-dimer testing yielded 15.0% (51/340) VTE. Applying age-adjusted D-dimer cut-offs to all patients aged 50 years or older resulted in a reduction of positive D-dimer results from 97.9% to 79.4%, without missing any VTE.

Conclusions

Although D-dimer testing contributes to the diagnostic work-up of VTE, GPs have a high detection rate for VTE in patients who they urgently refer to secondary care based on clinical assessment only.

Keywords: general medicine (see internal medicine), primary care, epidemiology, thromboembolism

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study that explored the actual use of D-dimer tests in venous thromboembolic events suspected patients in general practice and the diagnostic pathways of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in one demarcated geographical region during 1 year.

We carefully investigated the patient flow of all general practitioner-referred patients and investigated the D-dimer use in all primary care patients in this region.

We were unable to create a clear overview of the non-referred patients and to reliably determine some aspects of the consultation and patient history from the medical records.

Introduction

The annual incidence of venous thromboembolic events (VTEs)—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE)—in high-income countries is approximately 70–270 per 100 000 people.1–3 It is vital to quickly recognise a VTE and initiate treatment, in order to prevent further morbidity, disability or death.3 4 However, diagnosing VTEs is a challenge in general practice, as symptoms may be non-specific and the clinical presentation can vary strongly.5 6

In the current diagnostic pathways for suspected VTE, it is recommended that general practitioners (GPs) combine clinical decision rules with a D-dimer test in patients with a low clinical pretest probability for VTE.6–10 A low Wells score combined with a D-dimer value below 500 µg/L can safely exclude a VTE. Furthermore, using an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off in patients ≥50 years seems to be safe.11–18 Currently, GPs in the Netherlands have access to D-dimer through routine laboratory tests with results available within a few hours. Using a point-of-care test (POCT) might speed up the diagnosis and inform the decision to refer to secondary care, as the results can immediately support clinical decision-making during the consultation. Many GPs would like to use a D-dimer POCT, although GPs express concerns about the reliability of POCTs in general.5 19 Moreover, user-friendliness of existing D-dimer POCTs varies.20

The actual use of routine laboratory D-dimer testing by GPs has not been investigated and might provide useful insights in how GPs currently test and refer VTE suspected patients (both low-risk and high-risk patients) and may inform possible future D-dimer POCT implementation. The primary aim of this study is to assess how many GP-referred VTEs are diagnosed during 1 year in one geographical region and to investigate the (urgent) referral pathway of VTE diagnoses, including the role of laboratory D-dimer testing. Moreover, we want to evaluate the possible effect of implementing an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off.

Method

Study design and setting

This is a historical cohort study (2015) in a demarcated geographical area in the Netherlands served by one non-academic hospital and primary care being provided by 47 general practices (83 GPs) to 161 503 inhabitants. Patients are primarily referred to this hospital and GPs in this area order laboratory tests via one local diagnostic primary care centre ‘MCC Omnes Centre for Diagnostics and Innovation’.

Patient selection

We analysed all patients who were diagnostically worked-up for suspected VTE in hospital or in whom the GP determined a D-dimer value in the year 2015. The cohort was constructed based on data from two sources: the medical registration archives of the hospital and the diagnostic testing database of the local diagnostic centre. From the hospital medical registration archives we selected all patients with a diagnosis-treatment code for DVT and/or PE in the study period. From the diagnostic testing database of the local diagnostic centre we selected all patients of whom the GP requested at least one D-dimer test in the study period. We excluded patients who were registered with a GP working outside the postal code area of the study region or who were not referred by a GP, for example, patients who were already admitted to hospital or were translocated from another hospital. Self-referrals and referrals from nursing home physicians were included and analysed as referrals from primary care.

Combining the two data sources resulted in three populations available for the analyses: patients urgently referred to hospital, patients non-urgently referred to hospital and patients in whom the GP determined a D-dimer but were not referred to hospital. Urgent referrals were defined as referral within 7 days. All referred patients could be divided into patients referred for suspected VTE based on GP clinical assessment only (hence without D-dimer) and patients referred for suspected VTE based on GP clinical assessment and D-dimer testing.

Data extraction and outcomes

For all urgently referred patients, data were extracted from digital clinical medical records by one researcher (EM) through accessing each patient record and recording data on the final diagnosis, diagnostic work-up and medical history of patients on a prespecified case record form. In case of doubt, patients were discussed with another researcher (AS). When more than one D-dimer test was performed or more than one diagnosis-treatment code was assigned in referred patients, we evaluated the clinically most relevant event, with the highest suspicion of a PE or DVT. In case a patient had more than one VTE in 2015 this was noted. Diagnoses reported in discharge letters were noted as exactly as possible and subsequently pooled into groups. The number of GP-requested D-dimer tests and D-dimer results in non-referred patients was extracted from the diagnostic testing database of the local diagnostic centre. All data were collected from October to December 2016.

The primary outcomes of this study were the total number of DVTs and PEs per year and diagnostic pathways of patients urgently referred to secondary care for suspected VTE (referred based on clinical assessment only or based on clinical assessment and D-dimer). Therefore, we registered the total number of GP-requested D-dimer tests, the D-dimer values, the time between D-dimer testing and the hospital visit, the final diagnoses after referral and patient characteristics. For the D-dimer value we used a cut-off of 500 µg/L. Additionally, we explored the use of an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off, defined as age x 10 within patients ≥50 years.13–16

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Data Editor V.23. Analyses consisted primarily of descriptive analyses to describe the study population, patient flow and D-dimer values, using frequencies, averages, medians or percentages. The total population size of 161 503 inhabitants was calculated by adding the number of patients of all included general practices, based on list sizes of practices provided by MCC Omnes. The incidence rate was calculated by dividing the total number of VTEs by the total population size.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or public were involved in the design and execution this study.

Results

Patient characteristics and VTE incidence

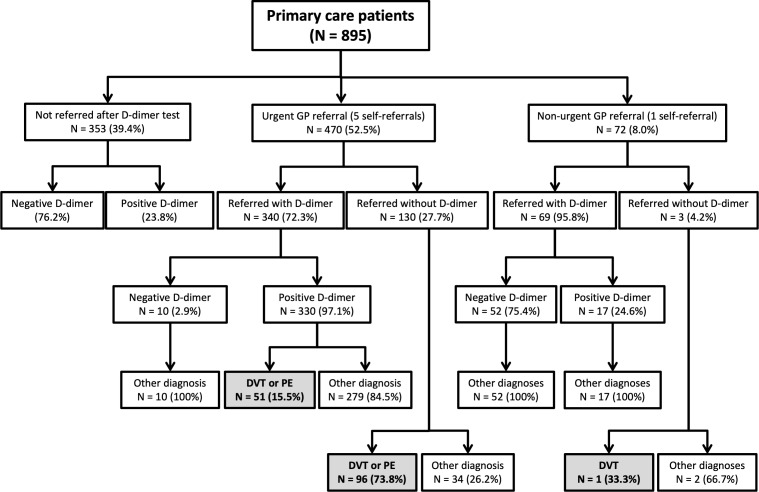

Figure 1 illustrates the patient flow of all included patients. We included 895 primary care patients, of which 148 were diagnosed with VTE in a total population of 161 503 inhabitants. Three (2.0%) patients had more than one VTE during 2015. The annual incidence of GP-referred VTE was 0.9 per 1000 inhabitants. GPs requested 821 D-dimer tests; two times in 34 patients and three times in 5 patients. An average of 5.1 D-dimer tests per 1000 inhabitants were performed by GPs.

Figure 1.

Patient flow and GP use of D-dimer test. In this figure only one D-dimer test and one clinical event per patient is shown. When more than one D-dimer test was performed or more than one diagnosis-treatment code was assigned in referred patients, we evaluated the clinically most relevant event, with the highest suspicion of a PE or DVT. DVT, deep vein thrombosis; GP, general practitioner; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Referral pathways

Four hundred and seventy (52.5%) patients were urgently referred to secondary care, 72 patients (8.0%) were referred non-urgently and 353 patients (39.4%) were not referred to secondary care (figure 1). Of all non-urgently referred patients, one self-referred patient was diagnosed with a DVT. About a quarter (23.8%) of patients not referred to secondary care had a positive D-dimer, with a median D-dimer value of 648.5 (501–3386).

Urgently referred patients

A total of 470 patients were urgently referred to secondary care for suspected VTE, which is 52.5% of all patients in this cohort. On average, these patients were 63 years old, and 38.9% were male (table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of urgently referred patients (n=470)

| Patient characteristics and D-dimer use | |

| Mean age, years (range) | 63 (18–95) |

| Gender, male (%) | 183 (38.9) |

| Number of GP determined D-dimer tests (%) | 340 (72.3) |

| Number of positive D-dimer tests, >500 µg/L (%) | 330 (97.1) |

| Median of D-dimer tests, µg/L (range) | 1041.5 (256–22 863) |

| Use of medication when referred to hospital | |

| Oral anticoagulation* (%) | 11 (2.3) |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitor (%) | 45 (9.6) |

| Medical history when referred to hospital | |

| Pregnancy* (%) | 5 (1.1) |

| Previous DVT/PE (%) | 100 (21.3) |

| Malignancy* (%) | 36 (7.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 61 (13.0) |

| Cardiac disorders* (%) | 96 (20.4) |

| Previous CVA/TIA (%) | 34 (7.2) |

| Hypertension (%) | 135 (28.7) |

| COPD (%) | 38 (8.1) |

| Renal insufficiency (%) | 16 (3.4) |

*Use of anticoagulants consisted of coumarin derivatives, heparins and direct oral anticoagulants; malignancy was defined as active malignancy, malignancy treated within past 6 months or palliation; pregnancy as current pregnancy or postpartum period (6 weeks postpartum); cardiac history included any cardiac disorder, for example, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction and bundle branch block.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Urgently referred patients based on clinical assessment and D -dimer

The majority of urgently referred patients (n=340, 72.3%) were referred based on the GP’s clinical assessment plus a D-dimer test (table 1). Of these patients 330 (97.1%) had a positive test (>500 µg/L), with a median D-dimer of 1072 µg/L (502–22,863) (table 2). In 51 of these 340 patients a VTE was diagnosed (15.0%), of which 19 (37.3%) patients had a PE, 21 (41.2%) a DVT and 11 (21.6%) a PE and DVT. No VTE was found among the 10 patients with a normal D-dimer test. Three hundred and twenty two patients (94.7%) were seen within 1 day after a D-dimer test was requested; average time between D-dimer test and hospital visit was 0.62 days.

Table 2.

GP determined D-dimer values of all urgently referred patients with a positive D-dimer value (>500 µg/L) (n=330)*

| Diagnoses | Median D-dimer value (range, µg/L) |

| All urgently referred patients (n=330) | 1072 (502–22 863) |

| VTE (n=51) | 3321 (982–21 345) |

| PE (n=19) | 1799 (1113–20 492) |

| DVT (n=21) | 4449 (1223–16 782) |

| Combination of PE and DVT (n=11) | 5718 (982–21 345) |

| Alternative diagnosis (n=279) | 928 (502–22 863) |

*Of all urgently referred patients (n=470), 340 were referred based on GP clinical assessment and D-dimer and 10 of those were negative (<500 µg/L).

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; GP, general practitioner; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolic events.

Urgently referred patients based on clinical assessment only

One hundred and thirty (27.7%) patients were urgently referred to secondary care based on clinical assessment only, hence without a D-dimer test. Of these, 96 (73.8%) were diagnosed with a VTE; 28 (29.2%) patients with a PE, 45 (46.9%) with a DVT and 23 (24.0%) patients had a combined diagnoses of PE and DVT.

VTE and alternative diagnoses in urgently referred patients

Hence in total, of all 470 urgently referred patients (both based on clinical assessment only and clinical assessment plus D-dimer) 147 (31.3%) were diagnosed with a VTE (table 3). Frequent alternative diagnoses were musculoskeletal disorders (14.9%), respiratory tract infections or other pulmonary disorders (11.3%) and oedema, and other vascular disorders (10.2%) (table 3).

Table 3.

Final diagnoses in patients urgently referred (within 7 days) to secondary care (n=470), based on hospital medical records.

| Final diagnoses | No of patients (%) |

| VTE | 147 (31.3) |

| PE | 47 (10.0) |

| DVT | 66 (14.0) |

| Combination PE and DVT | 34 (7.2) |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 70 (14.9) |

| Respiratory tract infections or other pulmonary disorders | 53 (11.3) |

| Pneumonia | 12 (2.6) |

| Oedema and other vascular disorders* | 48 (10.2) |

| (Skin)Infections of leg | 20 (4.3) |

| Erysipelas/cellulitis | 18 (3.8) |

| Thrombophlebitis | 28 (6.0) |

| Baker’s cyst | 20 (4.3) |

| Cardiac disorders | 10 (2.1) |

| Other diagnoses | 13 (2.8) |

| Unclear diagnosis/no diagnosis | 47 (10.0) |

| More than one differential diagnosis | 14 (3.0) |

*Including one mesenteric vein thrombosis.

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolic events.

Applying age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off in urgently referred patients

Among urgently referred patients with a D-dimer test, 287 patients were ≥50 years. Using a cut-off of 500 µg/L, 281 (97.9%) patients had a positive D-dimer value. Applying an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off value to this group would leave 228 (79.4%) patients with a positive D-dimer value; a reduction of 18.5%. No VTE would have been missed.

Discussion

Main findings

In this historical cohort study in a well-defined geographical area, we found an annual incidence of 0.9 VTE per 1000 inhabitants. GPs requested annually 5.1 D-dimer test per 1000 inhabitants. Of all urgently referred patients to secondary care, 31.3% was diagnosed with a VTE. Of those urgently referred based on clinical assessment only, 73.8% had a VTE, while in those referred based on clinical assessment and D-dimer 15.5% had a VTE. The use of an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off could have resulted in a reduction of 18.5% of positive D-dimer tests (97.9% to 79.4%) in the group of urgently referred patients ≥50 years, without missing any DVT or PE.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study that explored the actual use of D-dimer tests in general practice and the diagnostic pathway of DVT and PE in one demarcated geographical region during 1 year. We not only carefully investigated the patient flow of all GP-referred patients, we also investigated the D-dimer use in all primary care patients in this region.

Unfortunately, we were unable to create a clear overview of the non-referred patients, as we did not have patient’s permission to access GPs’ patient records. We can only speculate as to what reasons GPs had to not refer patients with a positive D-dimer test, for example, GPs may have used age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off values or reconsidered the appropriateness of performing the test in that particular patient, the patient may have refused to go into hospital or was sent to another hospital outside of the study region, or the patient might have died before arrival into hospital. This may have led to a slight underestimation of the number of VTEs in the study population. We tried to reduce this chance by selecting a specific demarcated geographical region where almost all GPs refer their patients to one hospital and where all GPs do all diagnostic tests in one diagnostic centre. We assume the number of potentially missed VTE cases will be less than approximately 10 cases (<7%), assuming the percentage of VTE in this group will not be higher than in referred patients with a positive D-dimer. We were unable to reliably determine some aspects of the consultation and patient history in the medical records, for example, components of the Wells score were missing in discharge letters of many patients and some aspects of the medical history might have been underestimated as these are not always fully reported in the records. Moreover, the final diagnosis was determined based on medical records instead of a uniform predefined assessment or adjudication committee. Some minor selection bias may have occurred as we only evaluated the most clinically suspected event in each patient.

Comparison with existing literature and recommendation in GP guidelines

We found an annual incidence of approximately one VTE per 1000 person-years at risk, which is comparable with incidence rates in other studies.1–3 In this study we found that of all urgently referred patients based on clinical assessment only, almost 75% of patients indeed had a VTE. This suggests that GP’s judgement in high-risk patients is remarkably good, which supports the current recommendation in the Dutch national guidelines that requesting a D-dimer test in these high-risk patients is not advisable and will only delay referral to secondary care.6–10 Of those urgently referred after D-dimer testing, 15.5% of patients was diagnosed with a VTE.

Nonetheless, it is important to note that, although almost 85% of patients urgently referred to secondary care with a positive D-dimer test did not have a VTE, a significant portion of these patients may still have had another clinically relevant diagnosis for which referral may have been wise or needed. A study by Erkens et al,21 found that 28.9% of patients suspected of a PE but in whom a PE was eventually ruled-out received another clinically relevant diagnoses; a positive Wells rule or a positive D-dimer test were positively associated with a higher probability of another clinically relevant disease.21

Applying the age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off to our primary care population again shows that VTE can be safely ruled out with the age-adjusted cut-off value in patients ≥50 years and may reduce the referral rate in patients aged 50 years and older by 18.5%.13–18

Implications for research and/or practice

Looking at the patient flow, we can see that the D-dimer test contributes significantly to the diagnostic work-up of VTE, but two-thirds of patients diagnosed with a VTE were found after clinical assessment only. We may speculate, although we did not have access to GP medical records, that these were patients with a high probability of VTE as estimated by the consulting GP and these patients were rightfully directly referred, in line with recommendations in the GP guidelines. Taking into account that a GP will infrequently use a D-dimer test in daily practice and the finding that GPs have a high detection rate for highly suspicious VTE, one might argue that replacing the laboratory D-dimer test by a D-dimer POCT is not directly necessary. Moreover, a D-dimer POCT may be used more often in patients without a clear or evidence-based indication, which will most likely—especially in the case of a non-specific test—lead to an increase in referrals to secondary care due to false positive tests. The closer proximity to a D-dimer POCT may also lead to a lower threshold for testing in high probability patients, which is not recommended by guidelines and may lead to a delay in referral.6–9 This effect of non-evidence-based testing (for other indications) has previously been seen with the introduction of the CRP POCT.22–24 Excessive test use and a possible increase in referrals in turn may lead to an increased number of patients being anticoagulated inappropriately, due to an increased number of false positive cases with leg ultrasonography and an increased number of overdiagnosis in patients with clinically insignificant subsegmental PEs.25 26 Furthermore, the low frequency of test use and potential excessive use of a D-dimer POCT also raises questions with regards to training and cost-effectiveness of such a POCT. Additionally, the use of D-dimer POCTs in routine clinical practice is insufficiently evaluated (in randomised studies) and qualitative and semi-quantitative test results pose additional challenges in interpretation. However, if a D-dimer POCT were to be implemented, careful monitoring is essential to assess its effect on the diagnostic work-up of patients with suspected VTE and the referral rate to secondary care.

Conclusion

Although D-dimer testing contributes to the diagnostic work-up of VTE, GPs have a high detection rate for VTE in patients they urgently refer to secondary care based on clinical assessment only.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been previously presented at the DEGAM-Kongress 2017 on 22 September in Düsseldorf and was included in the PhD dissertation of AMRS.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS, EM, G-JD, MK and JC created the research protocol and EM extracted data from digital clinical medical records and in case of doubt discussed patients with AS. AS, EM and JC performed the data analyses and these results were discussed with G-JD, HS and MK. AS and EM drafted the first manuscript and AS and JC revised the manuscript. AS, EM, G-JD, HS, MK, and JC all contributed to the decisions about how to present the data, organise and edit the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a Veni-grant, assigned to JWLC (91614078), of the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of Zuyderland Medical Centre in The Netherlands (METC 16-N-145).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, et al. . Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34:2363–71. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation 2003;107:14–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA, et al. . Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost 2007;98:756–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith SB, Geske JB, Maguire JM, et al. . Early anticoagulation is associated with reduced mortality for acute pulmonary embolism. Chest 2010;137:1382–90. 10.1378/chest.09-0959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schols AM, van Boekholt TA, Oversier LM, et al. . General practitioners' experiences with out-of-hours cardiorespiratory consultations: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012136 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, et al. . Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3033–80. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dupras D, Bluhm J, Felty C, et al. . Institute for clinical systems improvement: Venous Thromboembolism Diagnosis and Treatment, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Qaseem A, Snow V, Barry P, et al. . Current diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American academy of family physicians and the American college of physicians. Ann Fam Med 2007;5:57–62. 10.1370/afm.667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Diagnosing venous thromboembolism in primary, secondary and tertiary care. https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/venous-thromboembolism#path=view%3A/pathways/venous-thromboembolism/diagnosing-venous-thromboembolism-in-primary-secondary-and-tertiary-care.xml&content=view-index (Accessed Aug 2017).

- 10. The Dutch College of General Practitioners' working group deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. (GP guideline Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (second partial revision). Utrecht: Dutch College of General Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Büller HR, Ten Cate-Hoek AJ, Hoes AW, et al. . Safely ruling out deep venous thrombosis in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:229–35. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geersing GJ, Erkens PM, Lucassen WA, et al. . Safe exclusion of pulmonary embolism using the Wells rule and qualitative D-dimer testing in primary care: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012;345:e6564 10.1136/bmj.e6564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Righini M, Van Es J, Den Exter PL, et al. . Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to rule out pulmonary embolism: the ADJUST-PE study. JAMA 2014;311:1117–24. 10.1001/jama.2014.2135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL, et al. . Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f2492 10.1136/bmj.f2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andro M, Righini M, Le Gal G. Adapting the D-dimer cutoff for thrombosis detection in elderly outpatients. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2013;11:751–9. 10.1586/erc.13.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fuchs E, Asakly S, Karban A, et al. . Age-adjusted cutoff d-dimer level to rule out acute pulmonary embolism: a validation cohort study. Am J Med 2016;129:872–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schouten HJ, Koek HL, Oudega R, et al. . Validation of two age dependent D-dimer cut-off values for exclusion of deep vein thrombosis in suspected elderly patients in primary care: retrospective, cross sectional, diagnostic analysis. BMJ 2012;344:e2985 10.1136/bmj.e2985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flores J, García de Tena J, Galipienzo J, et al. . Clinical usefulness and safety of an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to exclude pulmonary embolism: a retrospective analysis. Intern Emerg Med 2016;11:69–75. 10.1007/s11739-015-1306-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Howick J, Cals JW, Jones C, et al. . Current and future use of point-of-care tests in primary care: an international survey in Australia, Belgium, The Netherlands, the UK and the USA. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005611 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geersing GJ, Toll DB, Janssen KJ, et al. . Diagnostic accuracy and user-friendliness of 5 point-of-care D-dimer tests for the exclusion of deep vein thrombosis. Clin Chem 2010;56:1758–66. 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Erkens PM, Lucassen WA, Geersing GJ, et al. . Alternative diagnoses in patients in whom the GP considered the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Fam Pract 2014;31:670–7. 10.1093/fampra/cmu055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Minnaard MC, van de Pol AC, Hopstaken RM, et al. . C-reactive protein point-of-care testing and associated antibiotic prescribing. Fam Pract 2016;33:408–13. 10.1093/fampra/cmw039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cals JW, Chappin FH, Hopstaken RM, et al. . C-reactive protein point-of-care testing for lower respiratory tract infections: a qualitative evaluation of experiences by GPs. Fam Pract 2010;27:212–8. 10.1093/fampra/cmp088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Engström S, Mölstad S, Lindström K, et al. . Excessive use of rapid tests in respiratory tract infections in Swedish primary health care. Scand J Infect Dis 2004;36:213–8. 10.1080/00365540310018842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goodacre S, Sampson F, Thomas S, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for deep vein thrombosis. BMC Med Imaging 2005;5:6 10.1186/1471-2342-5-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. When a test is too good: how CT pulmonary angiograms find pulmonary emboli that do not need to be found. BMJ 2013;347:f3368 10.1136/bmj.f3368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.