Abstract

Objectives

To investigate trends in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk following breast cancer using national registry data.

Methods

A nationwide cohort study was conducted, comprising 163 881 women with in situ (7.6%) or invasive (92.4%) breast cancer and women of the general population, ranging from 3 661 141 in 1996 to 4 566 573 in 2010. CVD mortality rate in women with and without breast cancer and hospitalisation rate after breast cancer were calculated for the years 1996–2010. Age-adjusted CVD and breast cancer mortality within 5 years after breast cancer admission (1997–2010) were compared with 1996 calculated with a Cox proportional hazard analysis.

Results

The absolute 10-year CVD mortality risk following breast cancer decreased from 56 per 1000 women in 1996 to 41 in 2005 (relative reduction=27.8%). In the general population, this decreased from 73 per 1000 women in 1996 to 55 in 2005 (–23.9%). The absolute risk of CVD hospitalisation within 1 year following breast cancer increased from 54 per 1000 women in 1996 to 67 in 2009 (+23.6%), which was largely explained by an increase in hospitalisation for hypertension, pulmonary embolism, rheumatoid heart/valve disease and heart failure. The 5-year CVD mortality risk was 42% lower (HR 0.58, 95% CI=0.48 to 0.70) for women admitted for breast cancer in 2010 compared with 1996.

Conclusions

CVD mortality risk decreased in women with breast cancer and in women of the general population, with women with breast cancer having a lower risk of CVD mortality. By contrast, there was an increase in hospitalisation for CVD in women with breast cancer.

Keywords: breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, trends, morbidity, mortality, cardiotoxicity

Strengths and limitation of this study.

This nationwide cohort study is the first study that gives insight in trends in the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and hospitalisation for CVD following breast cancer between 1996 and 2010 in the Netherlands.

Trends in CVD mortality following breast cancer were compared with CVD mortality of the general population. Absolute risks were standardised according to the age distribution of women of the general population.

The validation study showed high accuracy of breast cancer discharge codes notified in the hospital discharge register.

From 2005 onwards, the participation of hospitals in registering patients’ discharges decreased from 100% coverage to 89% in 2010, and therefore, not all women with breast cancer in the Netherlands could be identified.

This study had no information on breast cancer characteristics and CVD risk factors other than type of breast cancer diagnosis (in situ/invasive) and age.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women worldwide.1 Breast cancer survival is high in developed countries due to early detection and effective treatments.1–3 The combination of high breast cancer incidence rates and high survival rates has resulted in a large group of breast cancer survivors.1 In 2018, the estimated number of women who have survived breast cancer after being diagnosed within the preceding 5 years is 6.87 million worldwide.1 Many of these survivors will die of other medical conditions than breast cancer. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is an important cause of death in women of the general popualtion,4 and also in women with breast cancer.5

Previous studies reported associations between some breast cancer treatments and the development of CVD, including anthracycline-based chemotherapy,6 7 trastuzumab,8 and radiotherapy treatments.9 10 The highest risks of treatment-induced cardiotoxicity are seen in patients with preexisting CVD risk factors such as hypertension and high age.11 12

In the last decade, many efforts have been made to reduce the risk of CVD induced by breast cancer treatments. Cancer therapies with a lower risk of cardiotoxicity are increasingly being chosen for patients with a high risk of CVD if this does not impair cancer-specific outcomes.13 14 Cardiac monitoring before, during, and after treatment with trastuzumab to detect reversible cardiotoxicity is recommended care in the Netherlands.14–16 In parallel, women with breast cancer have also been exposed to improvements in pharmacological prevention of CVD with antihypertensive and statins and non-pharmacological prevention programmes such as antitobacco programmes, and campaigns focusing on the importance of physical activity.15 17 However, no recent trend data about CVD mortality and hospitalisation after breast cancer are available. The purpose of this study was to investigate trends of risks in CVD mortality and CVD hospitalisation following breast cancer diagnosis in 1996–2010 compared with those in women without breast cancer in the Netherlands.

Methods and materials

Study population

Data for the present study were obtained from three Dutch national registries. The Dutch population register was used to obtain demographic characteristics, available from 1995 to 2015. Hospital discharge register was used to identify women admitted for breast cancer and CVD hospitalisation, available until 2010. The cause of death registry was available until 2015, providing data on causes of death (ie, CVD, breast cancer or any other cause).

Details of the registries and linkage procedures used to obtain data for this study have been described previously.18 Briefly, all registries have a unique record identification number, which is assigned to each resident in the Netherlands. This number is a combination of birth date, sex, and postal code, and is unique for 84% of the Dutch population. Linkage of data from the different registries was performed in a secured environment of Statistics Netherlands and complies with the privacy legislation in The Netherlands and with the Declaration of Helsinki.19 For this study using national registries, no approval of the ethics committee is required.

For the present study, women from all ages with a first hospital admission for in situ (ICD-9: 233, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10]: D05) and invasive breast cancer (ICD-9: 174, ICD-10: C50) between 1996 and 2010 were identified. Surgical removal of breast cancer is standard procedure for breast cancer treatment in the Netherlands. We estimate that <5% of the patients with breast cancer were missed due to refusal of surgery.20

For every identified woman with a breast cancer hospital admission, it was examined if she had a previous hospital admission for breast cancer in the preceding year. In total, the breast cancer study population consisted of 163 881 women, 12 378 (7.6%) were diagnosed with in situ and 151 503 (92.4%) with invasive breast cancer. For the comparison with the general population, women of the general population without breast cancer were identified, ranging from 3 661 141 in 1996 to 4 566 573 in 2010. For this analysis, we focused on women from 40 years or older, because in breast cancer women younger than 40 the prevalence of CVD mortality per year was too low to perform accurate standardisation.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved directly in this study.

Outcome assessment

Patients were followed until 31 December 2015 for death from CVD and until 31 December 2010 for hospitalisation due to CVD. Causes of death were coded according to the ICD-10: death from CVD (A18.2, A52.0, D18, G45, I00–I99, K55, M30–M31, P29.3, Q20–Q28, R00–R02, R07.1–R07.4, R09.8, R16.1, R23.0, R55, R57.0, R58, R59, R60, R94.3), death from breast cancer (C50, D05) and death from any cause. Causes of death were based on the primary cause of death, that is, the underlying disease that led to death. Hospitalisation due to CVD was coded according to ICD-9: 017.2, 093, 228, 289.1–289.3, 390–459, 557, 745–747, 780.2, 782.3, 7825, 7826, 785, 786.50–786.59, 789.2, 794.30–794.39.

Validation of breast cancer hospital discharge codes

A validation study was performed to assess the accuracy of breast cancer discharge codes notified in the hospital discharge register. In total, 90 patients from the University Medical Center Utrecht were randomly selected (five to six patients per year from 1996 to 2010). Medical records of these patients were manually checked for discharge ICD-9 code and discharge date. Breast cancer diagnosis was confirmed in all patients (online supplementary table A). Six hospital discharge register codes were slightly incorrect as the date of discharge differed with the correct date: 1 day (n=1), 2 weeks (n=2), 2 months (n=2) and 5 months (n=1).

bmjopen-2018-022664supp001.pdf (94.5KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Median (IQR) was calculated to describe variables with skewed distribution. Time at risk for CVD mortality and hospitalisation started at date of breast cancer admission until date of CVD mortality or hospitaliation, respectively. Follow-up time was censored at the date of death for patients who died from causes other than CVD, breast cancer, or end of study (31 December 2015 for mortality and 31 December 2010 for CVD hospitalisation). Absolute risks were standardised according to the age distribution of women of the general population aged 40 years and older in 1996, with 5-year age groups, and presented per year of breast cancer admission (1996–2010). Absolute risk of death from CVD (per 1000 women) was calculated within 5, 7, and 10 years after year of breast cancer admission and reference year for women of the general population. Absolute risk of CVD hospitalisation (per 1000 women) was calculated within 1, 3, and 5 years after year of breast cancer admission. Shorter time periods for CVD hospitalisation were chosen because it was expected that possible cardiotoxic effects of breast cancer treatments may have a direct effect on CVD hospitalisation but less on CVD mortality. Previous studies showed an association between heart failure and coronary heart disease and prior exposure to chest irradiation,9 10 chemotherapy,21 22 trastuzumab23 24 and aromatase inhibitors.25 Therefore, we investigated whether hospitalisations for heart failure, coronary heart disease, and other cardiovascular diagnoses changed over the years. To account for competing risks, we also provided cardiovascular mortality expressed per 10 000 person-years. CVD mortality rates per 10 000 person-years were calculated within 5 and 10 years after breast cancer admission by age group: 40–50, 50–64 and ≥65 years. Lastly, a Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate the age-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of death from CVD and death from breast cancer within 5 years after breast cancer admission for each year (1997–2010) compared with 1996. Two-sided α with p<0.05 was designated as significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS V.22.0.

Results

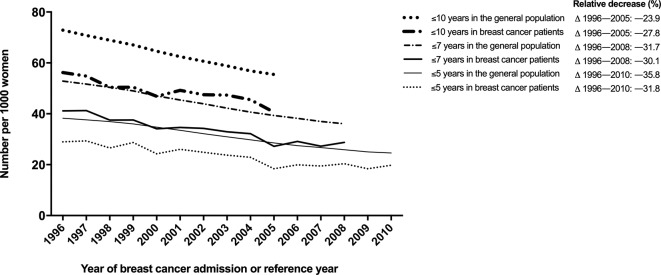

The majority of patients (51.3%) were 60 years or older at time of breast cancer admission (tables 1 and 2). Up to 2015, 5.6% of patients died of CVD and 22.7% of patients died of breast cancer (table 1). Death from CVD mainly occurred among patients aged 60 years or older (93.4%). After a median follow-up of 4.3 years (IQR=1.7–8.0) following breast cancer, 19.7% of patients were hospitalised for CVD (table 2). Seventy per cent of women with breast cancer with a hospital admission for CVD during follow-up were 60 years or older at time of breast cancer treatment (table 2). Overall, the absolute risk of death from CVD is lower in women with breast cancer compared with women from the general population. The CVD mortality rate following breast cancer decreased from 56 per 1000 women in 1996 to 41 per 1000 women in 2005 (relative reduction of 27.8%, figure 1). In the general population, this decreased from 73 per 1000 women in 1996 to 55 per 1000 women in 2005 (relative reduction of 23.9%). The relative risk for 5-year, 7-year, and 10-year CVD mortality for women with breast cancer compared with women from the general population remained similar over time (figure 1).

Table 1.

Deaths from cardiovascular disease among 163 881 women with breast cancer

| Total breast cancer population | Breast cancer patients who died from CVD | Breast cancer patients who died from breast cancer | |

| Breast cancer patients, n (%)* | 163 881 (100) | 9115 (5.6) | 37 187 (22.7) |

| Type of breast cancer, n (%) | |||

| In situ | 12 378 (7.6) | 483 (5.3) | 607 (1.6) |

| Invasive | 151 503 (92.4) | 8632 (94.7) | 36 580 (98.4) |

| Calendar period of breast cancer admission, n (%)† | |||

| 1996–1999 | 39 485 (24.1) | 3540 (38.8) | 12 698 (34.1) |

| 2000–2003 | 44 211 (27.0) | 2936 (32.2) | 10 946 (29.4) |

| 2004–2007 | 45 378 (27.7) | 1825 (20.0) | 8882 (23.9) |

| 2008–2010 | 34 807 (21.2) | 814 (8.9) | 4661 (12.5) |

| Age at breast cancer admission in years, n (%) | |||

| <50 | 36 720 (22.4) | 121 (1.3) | 8777 (23.6) |

| 50–59 | 43 054 (26.3) | 481 (5.3) | 8664 (23.3) |

| 60–69 | 39 144 (23.9) | 1613 (17.7) | 7985 (21.5) |

| 70–79 | 29 555 (18.0) | 3640 (39.9) | 7111 (19.1) |

| >79 | 15 408 (9.4) | 3260 (35.8) | 4650 (12.5) |

| Follow-up time in years | |||

| Median (IQR) | 8.5 (5.3–12.7) | 6.3 (3.3–10.0) | 3.1 (1.2–6.2) |

| Follow-up time intervals in years, n (%) | |||

| <1 | 10 256 (6.3) | 692 (7.6) | 8044 (21.6) |

| 1–4 | 26 054 (15.9) | 2921 (32.0) | 16 897 (45.4) |

| 5–9 | 61 602 (37.6) | 3232 (35.5) | 8664 (23.3) |

| >9 | 65 969 (40.3) | 2270 (24.9) | 3582 (9.6) |

| Interval years between breast cancer admission and death, n (%) | |||

| <5 | 36 301 (54.4) | 5052 (55.4) | 24 941 (67.0) |

| 5–9 | 18 912 (28.4) | 2686 (29.5) | 8664 (23.3) |

| >9 | 11 403 (17.1) | 1377 (15.1) | 3582 (9.6) |

*Percentage of total breast cancer population (n=163 881).

†Data on cause of death were available until 2015. Absolute risks of death from CVD decrease with more recent calendar period.

CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Table 2.

Hospitalisations for cardiovascular disease among 163 881 women with breast cancer

| Total breast cancer population | Breast cancer patients hospitalised for CVD | |

| Breast cancer patients, n (%)* | 163 881 (100.0) | 32 276 (19.7) |

| Type of breast cancer, n (%) | ||

| In situ | 12 378 (7.6) | 2144 (6.6) |

| Invasive | 151 503 (92.4) | 30 132 (93.4) |

| Calendar period of breast cancer admission, n (%)† | ||

| 1996–1999 | 39 485 (24.1) | 11 135 (34.5) |

| 2000–2003 | 44 211 (27.0) | 10.564 (32.7) |

| 2004–2007 | 45 378 (27.7) | 7687 (23.8) |

| 2008–2010 | 34 807 (21.2) | 2890 (9.0) |

| Age at breast cancer admission in years, n (%) | ||

| <50 | 36 720 (22.4) | 4155 (12.9) |

| 50–59 | 43 054 (26.3) | 6507 (20.2) |

| 60–69 | 39 144 (23.9) | 8582 (26.6) |

| 70–79 | 29 555 (18.0) | 8713 (27.0) |

| >79 | 15 408 (9.4) | 4319 (13.4) |

| Follow-up time in years | ||

| Median (IQR) | 4.3 (1.7–8.0) | 3.2 (1.1–6.6) |

| Follow-up time intervals in years, n (%) | ||

| <1 | 27 276 (16.6) | 7620 (23.6) |

| 1–4 | 64 138 (39.1) | 13 365 (41.4) |

| 5–9 | 47 665 (29.1) | 8038 (24.9) |

| >9 | 24 802 (15.1) | 3253 (6.6) |

| Interval years between breast cancer admission and CVD hospitalisation, n (%) | ||

| <1 | 8766 (5.3) | 8766 (27.2) |

| <3 | 17 485 (10.7) | 17 485 (54.2) |

| <5 | 23 273 (14.2) | 23 273 (72.1) |

*Percentage of total breast cancer population (n=163 881).

†Data on hospital admissions were available until 2010. Absolute risks of hospitalisation for CVD decrease with more recent calendar period.

CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Figure 1.

Trends in age-standardized 5-year, 7-year, and 10-year cardiovascular disease mortality per 1000 patients with breast cancer and women from the general population. Relative reduction (%) shows the relative change in cardiovascular disease mortality compared with reference year 1996.

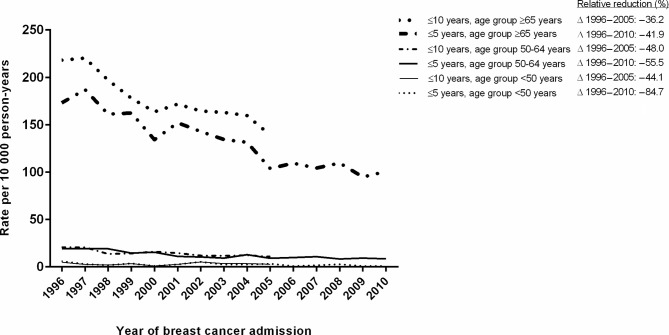

Women admitted to the hospital with breast cancer in 2010 had 42% lower (HR 0.58, 95% CI=0.48 to 0.70) age-adjusted 5-year risk of death from CVD compared with those in 1996 (table 3). Furthermore, women admitted in 2010 had 51% lower (HR 0.49, 95% CI=0.45 to 0.52) age-adjusted 5-year risk of death from breast cancer compared with those in 1996 (table 3). The 10-year CVD mortality rate after a breast cancer admission in 2005 was 139 per 10 000 person-years for patients aged 65 years or older, 11 per 10 000 person-years for patients aged between 50 and 64 years and 3 per 10 000 person-years for patients younger than 50 years (figure 2). Death from CVD after breast cancer admission decreased among all age groups. The 10-year CVD mortality rate decreased from 218 per 10 000 person-years in 1996 to 139 per 10 000 person-years in 2005 (relative decrease of 36.2%) for patients aged 65 years or older, from 21 to 11 (relative reduction of 48%) for patients aged between 50 and 64 years and from 5 to 3 (relative reduction of 44.1%) for patients aged younger than 50 years.

Table 3.

Relative risk of death from cardiovascular disease and breast cancer within 5 years after breast cancer admission among 163 881 women with breast cancer

| Year of breast cancer admission | Five-year CVD mortality | Five-year breast cancer mortality |

| HR* (95% CI) | HR* (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 1 | 1 |

| 1997 | 1.04 (0.88 to 1.23) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) |

| 1998 | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.01) | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.98) |

| 1999 | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.14) | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.90) |

| 2000 | 0.79 (0.66 to 0.94) | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.80) |

| 2001 | 0.86 (0.73 to 1.02) | 0.74 (0.70 to 0.79) |

| 2002 | 0.81 (0.69 to 0.96) | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.78) |

| 2003 | 0.75 (0.63 to 0.89) | 0.66 (0.62 to 0.71) |

| 2004 | 0.73 (0.61 to 0.86) | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.75) |

| 2005 | 0.58 (0.48 to 0.70) | 0.66 (0.62 to 0.70) |

| 2006 | 0.63 (0.52 to 0.75) | 0.63 (0.59 to 0.68) |

| 2007 | 0.60 (0.50 to 0.75) | 0.58 (0.54 to 0.62) |

| 2008 | 0.62 (0.52 to 0.74) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.58) |

| 2009 | 0.55 (0.46 to 0.66) | 0.54 (0.50 to 0.58) |

| 2010 | 0.58 (0.48 to 0.70) | 0.49 (0.45 to 0.52) |

*HRs are adjusted for age.

CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Figure 2.

Trends in 5-year and 10-year cardiovascular disease mortality rates in women with breast cancer per 10 000 person-years by age. Relative reduction (%) shows the relative decline in cardiovascular mortality rates compared with reference year 1996.

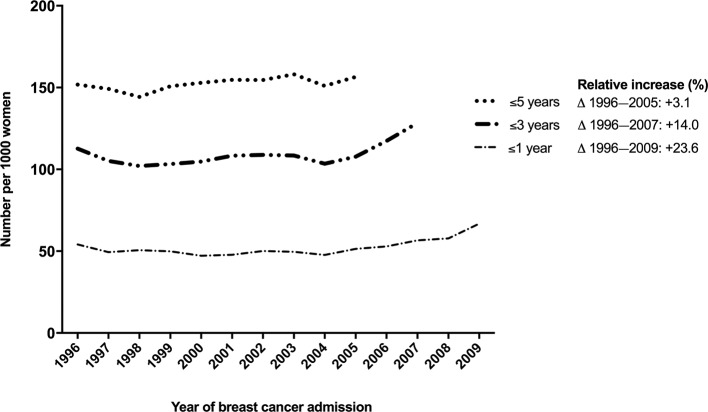

The absolute risk of hospitalisation for CVD in the first year after breast cancer increased from 54 per 1000 women in 1996 to 67 per 1000 women in 2009 (increase of 13 hospital admissions per 1000 women with breast cancer, figure 3). The increase in hospitalisations for CVD in the first year after breast cancer was mainly due to an increase in hospitalisations for high blood pressure. Hospitalisation for high blood pressure increased from 6.7 in 1966 to 11.0 hospitalisation in 2009 per 1000 women with breast cancer, accounting for 29% of the total increase in CVD hospitalisations in the first year after breast cancer. Pulmonary embolism rose from 4.4 in 1996 to 6.6 hospitalisations in 2009 per 1000 women with breast cancer, similar to 15% of the total CVD hospitalisations increase. Rheumatic heart disease/valve disease and heart failure rose from 1.4 to 2.5 and 4.7 and 5.6 per 1000 women with breast cancer during the same time period, accounting for 8% and 7% of the increase in CVD hospitalisations, respectively.

Figure 3.

Trends in 1-year, 3-year and 5-year age-standardised number of cardiovascular disease hospitalisations per 1000 women with breast cancer. Relative reduction (%) shows the relative decline in cardiovascular mortality rates compared with reference year 1996.

Discussion

Like in the general population, the risk of death from CVD has decreased in women with breast cancer between 1996 and 2010, and mainly occurred among patients aged over 60 years. Women with breast cancer had a lower absolute risk of death from CVD than women of the general population. Over time, the absolute burden of CVD in terms of hospitalisation has increased and is considerable with nearly one out of five women having a CVD hospital admission.

In developed parts of the world, including USA and Europe, the absolute risk of death from CVD have decreased.17 26 The decrease in deaths from coronary artery disease was for around 50% attributable to the increased use of pharmacological treatments after heart failure and myocardial infarction.27 28 The other half was explained by reductions in risk factors like hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, smoking and physical activity.27 28

Similar to our study, Riihimäki et al. (2012) showed that the absolute risk of death from CVD, after a maximum follow-up of 19 years, is lower in women with breast cancer (27.1%) than in women from the general population (44.0%).29 They investigated the risk of death from CVD using nationwide registration data and comparing all women diagnosed with breast cancer with women from the general population without a breast cancer diagnosis.29 This risk of death from CVD in women with breast cancer and the general population reported by Riihimäki et al. (2012) is higher than in our study, and this can be explained by the longer follow-up (1987–2006 vs 1996–2015) and the higher risks of CVD in the earlier years.29 Bradshaw et al. (2016) reported a higher absolute risk of death from CVD in women with breast cancer (9.4%) than in women from the general population (7.4%) after a maximum follow-up of 13.5 years (from 1996 to 2010).30 They also found a higher relative risk of death from CVD in women with breast cancer after 7 years following diagnosis compared with women from the general population (HR 1.8, 95% CI=1.3 to 2.5), adjusted for age and CVD risk factors.30 In that study, women with breast cancer were invited to participate, which may have resulted in a selected study population of patients with good prognosis. Patients with early stage breast cancer have a higher risk of death from CVD than patients with a poor prognosis as breast cancer is a competing risk.31

In the current study, we found that death from CVD mainly occurred among older women with breast cancer. This is in line with a study from Sweden on the prognosis of women with breast cancer.31 They showed that 24% of women aged 65 years and above died of CVD within 10 years after breast cancer.31 High age is one of the most important risk factors of CVD,32 and therefore older women with breast cancer have a higher risk of dying of CVD than younger women with breast cancer.13 14 Moreover, in the current study, we showed that older women with breast cancer had the least improvement in CVD mortality over time compared with younger women with breast cancer. It seems that older women with breast cancer do not benefit as much younger women from the worldwide improvements in CVD risk management and CVD treatments.

The results of our study show that the absolute risk of hospitalisation for CVD in the first year after breast cancer increased with 23.6% between 1996 and 2009. Seven per cent of this increase was caused by heart failure. This was less than we expected as heart failure shortly after therapy is a well-known side effect of systemic treatment including trastuzumab8 and anthracycline-based chemotherapies.6 7 Trastuzumab is a targeted therapy used to treat women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer (approximately one in five patients).33 Since 2004, trastuzumab is used as adjuvant therapy for early breast cancer.34 This therapy may have resulted in more hospital admissions for heart failure as the most concerning adverse effect of trastuzumab is in particular reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and heart failure.35 The risk of heart failure is four times higher in patients treated with trastuzumab alone and seven times higher in patients treated with anthracycline plus trastuzumab.36 37 Another 29% of the increase in hospitalisation for CVD was caused by high blood pressure. Blood pressure elevation is a common side effect of cancer treatments with vascular endothelial growth factor signalling pathway inhibitors as, for example, bevacizumab. Bevacizumab is used to treat metastatic breast cancer and was introduced in Europe after 2004.38 39 However, since an extremely small proportion of patients are treated with bevacizumab, it is unlikely to explain the 34% increase in hospital admissions due to hypertension. Pulmonary embolism explained 15% of the increased number of CVD hospitalisations and is often caused by venous thromboembolism.40 This increase may be related to the thrombotic effect of the selective oestrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen.41 42 A Danish study reported that women treated with tamoxifen had a higher risk of pulmonary embolism during the first 2 years after exposure compared with women not receiving.41 Similar results have been reported by Cuzick.42

We acknowledge that this study has limitations. For every woman with a breast cancer hospital admission between 1996 and 2010, it was examined if she had a previous hospital admission for breast cancer in the preceding year. This method reduced the percentage of women with a previous hospital admission for breast cancer to 7%. Women who have been readmitted for breast cancer may have a worse breast cancer prognosis and therefore a lower risk of death from CVD. The risk of hospitalisation for CVD, however, may be higher among these women with a readmission for breast cancer, as they may have undergone previous (potential cardiotoxic) cancer therapy that resulted in CVD. From 2005 onwards, the participation of hospitals in registering patients’ discharges decreased from 100% coverage to 89% in 2010. As a result, not all women with breast cancer in the Netherlands were identified. The present study had no information on breast cancer characteristics and CVD risk factors other than type of breast cancer diagnosis (in situ/invasive) and age. Lastly, our validation study showed that in 3 out of 90 patients (3.3%) the date of discharge in the registry was incorrect by 2 or more months which is some cases may have led to a wrong classification of time between breast cancer admission and CVD mortality and/or hospitalisation.

To conclude, the current study shows that the risk of death from CVD in women with breast cancer and in women from the general population decreased in the last decades. Yet, we find an increase in the number of CVD hospitalisations after breast cancer. Future studies should investigate whether the increase in CVD hospitalisations within the first year continues to rise and assess the underlying processes of this increase in more detail.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

JB and IV were supported by an unrestricted grant ‘Facts and Figures’ from the Netherlands Heart Foundation.

Footnotes

JB and SAMG contributed equally.

Contributors: Conceptualisation: SAMG, JB, HMV and IV. Data curation: JB and IV. Formal analysis: JB. Funding acquisition: HMV, MLB and IV. Investigation: SAMG, JB, IV and HMV. Methodology: JB, SAMG, IV, HMV and MLB. Supervision: HMV, IV, MLB, DEG, DHJGvdB and JB. Visualisation: SAMG and JB. Writing—original draft: SAMG, JB, HMV, IV, MLB, DEG, DHJGvdB and JB.

Funding: The current project was conducted within the framework ‘Strategic PhD Partnership Program’ from the Board of Directors of the University Medical Center Utrecht.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Additionally, statistics Netherlands should give their consent.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2018. https://gco.iarc.fr/today (17 Februari 2019).

- 2. Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1784–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa050518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Levi F, et al. The decline in breast cancer mortality in Europe: an update (to 2009). Breast 2012;21:77–82. 10.1016/j.breast.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Global health observator. 2017. http://www.who.int/gho (Accessed 11 Oct 2017).

- 5. Gernaat SAM, Ho PJ, Rijnberg N, et al. Risk of death from cardiovascular disease following breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;164:537–55. 10.1007/s10549-017-4282-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pinder MC, Duan Z, Goodwin JS, et al. Congestive heart failure in older women treated with adjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3808–15. 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rehammar JC, Jensen MB, McGale P, et al. Risk of heart disease in relation to radiotherapy and chemotherapy with anthracyclines among 19,464 breast cancer patients in Denmark, 1977-2005. Radiother Oncol 2017;123:299–305. 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chavez-MacGregor M, Zhang N, Buchholz TA, et al. Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity among older patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:4222–8. 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.7884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;366:2087–106. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darby SC, Brønnum D, Correa C, et al. A Dose-response Relationship for the Incidence of Radiation-related Heart Disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;78:S49–S50. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, et al. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med 1979;91:710–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-91-5-710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Serrano C, Cortés J, De Mattos-Arruda L, et al. Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity in the elderly: a role for cardiovascular risk factors. Ann Oncol 2012;23:897–902. 10.1093/annonc/mdr348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2768–801. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, et al. Prevention and Monitoring of Cardiac Dysfunction in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:893–911. 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kones R. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: integration of new data, evolving views, revised goals, and role of rosuvastatin in management. A comprehensive survey. Drug Des Devel Ther 2011;5:325–80. 10.2147/DDDT.S14934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dutch Oncology guidelines. www.oncoline.nl.

- 17. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Writing Group Members American Heart Association Statistics Committee Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;133:e38–60. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koek HL, de Bruin A, Gast A, et al. Incidence of first acute myocardial infarction in the Netherlands. Neth J Med 2007;65:434–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reitsma JB, Kardaun JW, Gevers E, et al. [Possibilities for anonymous follow-up studies of patients in Dutch national medical registrations using the Municipal Population Register: a pilot study]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2003;147:2286–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Verkooijen HM, Fioretta GM, Rapiti E, et al. Patients' refusal of surgery strongly impairs breast cancer survival. Ann Surg 2005;242:276–80. 10.1097/01.sla.0000171305.31703.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith LA, Cornelius VR, Plummer CJ, et al. Cardiotoxicity of anthracycline agents for the treatment of cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Cancer 2010;10:337–2407. 10-337 10.1186/1471-2407-10-337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ewer MS, Ewer SM. Cardiotoxicity of anticancer treatments. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:547–58. 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suter TM, Cook-Bruns N, Barton C. Cardiotoxicity associated with trastuzumab (Herceptin) therapy in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Breast 2004;13:173–83. 10.1016/j.breast.2003.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Suter TM, Procter M, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac adverse effects in the herceptin adjuvant trial. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3859–65. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Foglietta J, Inno A, de Iuliis F, et al. Cardiotoxicity of Aromatase Inhibitors in Breast Cancer Patients. Clin Breast Cancer 2017;17:11–17. 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilkins E, Wilson L, Wickramasinghe K, et al. European cardiovascular disease statistics, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2388–98. 10.1056/NEJMsa053935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koopman C, Vaartjes I, van Dis I, et al. Explaining the Decline in Coronary Heart Disease Mortality in the Netherlands between 1997 and 2007. PLoS One 2016;11:e0166139 10.1371/journal.pone.0166139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Riihimäki M, Thomsen H, Brandt A, et al. Death causes in breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2012;23:604–10. 10.1093/annonc/mdr160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bradshaw PT, Stevens J, Khankari N, et al. Cardiovascular disease mortality among breast cancer survivors. Epidemiology 2016;27:6–13. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Colzani E, Liljegren A, Johansson AL, et al. Prognosis of patients with breast cancer: causes of death and effects of time since diagnosis, age, and tumor characteristics. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4014–21. 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117:743–53. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, et al. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1273–83. 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Florido R, Smith KL, Cuomo KK, et al. Cardiotoxicity From Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor‐2 (HER2) Targeted Therapies. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6 10.1161/JAHA.117.006915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Advani PP, Ballman KV, Dockter TJ, et al. Long-Term Cardiac Safety Analysis of NCCTG N9831 (Alliance) Adjuvant Trastuzumab Trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:581–7. 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.8413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moja L, Tagliabue L, Balduzzi S, et al. Trastuzumab containing regimens for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD006243 10.1002/14651858.CD006243.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bowles EJ, Wellman R, Feigelson HS, et al. Risk of heart failure in breast cancer patients after anthracycline and trastuzumab treatment: a retrospective cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:1293–305. 10.1093/jnci/djs317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maitland ML, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Initial assessment, surveillance, and management of blood pressure in patients receiving vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:596–604. 10.1093/jnci/djq091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Amit L, Ben-Aharon I, Vidal L, et al. The impact of Bevacizumab (Avastin) on survival in metastatic solid tumors--a meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e51780 10.1371/journal.pone.0051780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey DJ, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and the impact on survival in breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:70–6. 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hernandez RK, Sørensen HT, Pedersen L, et al. Tamoxifen treatment and risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a Danish population-based cohort study. Cancer 2009;115:4442–9. 10.1002/cncr.24508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cuzick J. Aromatase inhibitors in the treatment of breast cancer: Results of the ATAC trial. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2007;4:S16–S25. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022664supp001.pdf (94.5KB, pdf)