Abstract

Objectives

We sought to understand healthcare-seeking patterns and delays in obtaining effective treatment for rural Rwandan children aged 1–5 years by analysing verbal and social autopsies (VSA). Factors in the home, related to transport and to quality of care in the formal health sector (FHS) were thought to contribute to delays.

Design

We collected quantitative and qualitative cross-sectional data using the validated 2012 WHO VSA tool. Descriptive statistics were performed. We inductively and deductively coded narratives using the three delays model, conducted thematic content analysis and used convergent mixed methods to synthesise findings.

Setting

The study took place in the catchment areas of two rural district hospitals in Rwanda—Kirehe and Southern Kayonza. Participants were caregivers of children aged 1–5 years who died in our study area between March 2013 and February 2014.

Results

We analysed 77 VSAs. Although 74% of children (n=57) had contact with the FHS before dying, most (59%, n=45) died at home. Many caregivers (44%, n=34) considered using traditional medicine and 23 (33%) actually did. Qualitative themes reflected difficulty recognising the need for care, the importance of traditional medicine, especially for ‘poisoning’ and poor perceived quality of care. We identified an additional delay—phase IV—which occurred after leaving formal healthcare facilities. These delays were associated with caregiver dissatisfaction or inability to adhere to care plans.

Conclusion

Delays in deciding to seek care (phase I) and receiving quality care in FHS (phase III) dominated these narratives; delays in reaching a facility (phase II) were rarely discussed. An unwillingness or inability toadhere to treatment plans after leaving facilities (phase IV) were an important additional delay. Improving quality of care, especially provider capacity to communicate danger signs/treatment plans and promote adherence in the presence of alternative explanatory models informed by traditional medicine, could help prevent childhood deaths.

Keywords: paediatrics, community child health, quality in health care, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The large qualitative and quantitative dataset allowed us to explore delays in healthcare-seeking among caregivers of children aged 1–5 years who died in this area of Rwanda.

Our analysis led to the identification of an important additional source of delays that occurred after children left formal sector healthcare. We call these ’phase IV delays'.

As is the nature of qualitative research, these findings cannot be generalised beyond the study population, but may be used to guide similar explorations in comparable samples.

By characterizing a fourth delay, we adapt the three delays model of maternal mortality for use in understanding childhood mortality.

Background

Rwanda has reduced under-five (U5) mortality by more than two-thirds since 2000, one of only 12 low-income countries to achieve Millennium Development Goal (MDG) four.1–3 This progress, although exceptional by most measures, mirrors a global trend towards reduced childhood mortality and an epidemiological transition away from the most easily preventable causes of death.4 As proficiency is gained in tackling the ‘low-hanging fruit’ of child health, health systems must turn their attention to solving the more complex problems that remain.

Despite Rwanda’s remarkable progress, a child is still 10 times more likely to die before their fifth birthday in Rwanda than in most high-income countries.5 Evidence from other low-income countries suggests that the majority of these deaths will occur outside of a health facility and that late care-seeking is a significant contributing factor.6 7 Understanding family and community contexts will therefore be important for improvement.8 9 What beliefs and behaviours exist in homes and communities that delay care-seeking? What barriers do caregivers face when they decide to seek care and what challenges might an increasingly capable but complex health system pose for them?

These questions may best be answered by viewing healthcare-seeking pathways and the health system from the perspective of its users, an area of scholarship that is poorly represented in the literature in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC).10 This study aims to address the gap in knowledge by analysing verbal and social autopsy (VSA) data collected following all deaths of children aged 1–5 years in two rural districts in Rwanda.

Methods

Setting

During the study period, there were 23 health centres (HC) in Kirehe and Southern Kayonza serving a population of 538 405. HCs were staffed by nurses who provided inpatient and outpatient services.11 12 Community health workers (CHWs) provided integrated community case management of paediatric illnesses (c-IMCI).13 They diagnosed and treated pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria, monitored malnutrition and made referrals. An estimated average of one CHW served 50 people under age 5; there were two c-IMCI-trained CHWs per village.13 14 Kirehe was served by one district hospital and Kayonza by two. The study was conducted in the catchment area of one hospital in Kirehe and another in Kayonza. Area households in the two districts were located a median 3.5 km from their closest HC.11 Community-based health insurance (CBHI, also referred to as ‘Mutuelle de Santé' or ‘mutuelle’) was available in the study districts and achieved over 90% coverage in Rwanda overall (Makaka et al, 2012).15 The catchment area for this study was rural and the majority of families relied on subsistence agriculture. Paved roads connected the main towns, and unpaved roads extended to most communities. Homes were predominantly made of natural materials such as earth and thatch and few communities had access to electricity. According to the 2014 Rwandan Demographic and Health Survey, nearly 40% of the population lived below the poverty line, although nearly all women in Kirehe and Kayonza worked in agriculture. Educational attainment was low in both areas, with most women not having completed primary school.16

Study design

Data were collected through VSAs with caregivers of 259 U5s who died between March 2013 and February 2014. VSA is a process used to assign causes of death in cases where no standard autopsy was done and social autopsy augments the structured interview of a verbal autopsy with open-ended questions about the beliefs, decisions and perspectives of those who cared for the decedent.10 17–24 Quantitative and qualitative data were collected during one visit with a family. Deaths were identified through health records, Rwandan Ministry of Health (RMOH) reporting systems and the Monitoring of Vital Events Using Information Technology programme in which CHWs reported vital events by telephone. CHWs then helped locate families, and families who consented were interviewed between 3 weeks and 1 year after the death. The minimum waiting period of 3 weeks was selected considering the Rwandan custom of a formal 1-week mourning period and literature from other countries suggesting that several weeks is an appropriate delay.25 26 Importantly, families could decline participation and could choose a time for the interview if they consented. This paper is a subanalysis of VSA data of children between the ages of 1 year and 5 years. This age range was chosen because it includes children with shared developmental characteristics (eg, the ability to crawl/walk), clinical characteristics (eg, causes of pneumonia) and social experiences (eg, not being in primary school).

Quantitative data were collected using the validated WHO 2012 verbal autopsy semi-structured interview tool (InterVA4)27 and supplemented by questions from the RMOH’s Death Audit Tool and the 2010 Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey. Trained interviewers used handheld electronic devices and conducted semi-structured interviews in the local language, Kinyarwanda. Informants were asked to describe events surrounding the death of the child. Segments during which interviewees expanded on symptoms, decision-making, care-seeking and perceptions of care received were transcribed and then back-transcribed from Kinyarwanda to English for quality and accuracy review.

Patient and public involvement

The research question was informed by the work of Partners in Health/Inshuti Mu Buzima (PIH/IMB), which has supported the RMOH to strengthen healthcare delivery and systems in Kirehe and Southern Kayonza districts since 2005. This VSA project was part of a larger initiative to better understand and reduce U5 mortality. Patients were not involved in the recruitment to and conduct of the study, nor were they involved in the design of the study. However, as a service delivery organisation, PIH/IMB has a deep experience with patients and their families/caregivers that helped shape the study. Aggregated early results were shared with the MOH and IMB in a timely manner to facilitate improved healthcare delivery.

Analysis

We used the three delays model28 as a framework to begin our thematic content analysis. This model was originally developed to understand maternal mortality.28 Phase I delays relate to deciding to seek care, phase II delays occur while trying to reach a facility and phase III delays occur after arrival at a facility in the form of poor quality of care. We use the Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems framework to understand high-quality care. Specifically, high-quality care includes competent care and systems, positive user experience as well as better health, confidence in the system and economic benefit.29

A mix of inductive and deductive coding was used to develop a codebook,30 which was discussed and revised by an interdisciplinary team of researchers, physicians and public health professionals. A subset of interviews (11) were double coded to ensure inter-rater reliability and then the codebook was applied to the dataset until saturation of codes was reached at 77 interviews. Iterative thematic analysis using coding, recoding, categorisation and reorganisation was used to further develop the themes and generate hypotheses. Dedoose was used for qualitative and mixed methods analysis (V.7.5.9, SocioCultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, California, USA).

The most likely cause of death (COD) was determined using InterVA4.27 COD and sociodemographic variables from verbal autopsies were analysed using descriptive statistics. Quantitative analytics were performed using STATA V.14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Associations between descriptive variables and qualitative themes were explored using a convergent mixed methods approach.31 This approach is recommended by experts to better understand complex phenomenon, such as care-seeking behaviour, because it helps uncover patterns that may not have been accessible through only quantitative data analysis or only qualitative data analysis.32 Excerpts were first organised by phase of delay and then divided by quantitative variables. These variables were chosen based on hypotheses which were generated during the qualitative analysis of the interviews. Hypotheses included 1) maternal education impacts care-seeking by giving caregivers more access to accurate health information, 2) children who died at home experienced more phase I delays, 3) less common causes of death are associated with more phase III delays. Thematic analysis of these subgroups of excerpts was conducted to identify divergent themes. Interviews were coded and analysed until saturation of codes was achieved, ie, saturation was achieved when no new codes or ideas were identified.33

Verbal consent was deemed permissible by two ethics review boards. A consent form was read to potential participants by Kinyarwanda-speaking data collectors who also answered questions. Participants were asked to verbally confirm that the consent was understood. Data collectors were trained in sensitivity, patience and consideration with families who had lost a child. Each interview was assigned a number that matched with caregiver identifying information and was stored in a separate file in a secure location. No individual identifiers were recorded on the data collection forms.

Results

We identified 259 deaths of children aged 1–5 years (table 1). Saturation of codes was reached at 77 interviews. The average age at death of the 77 children was 2.5 years. The majority were male (57%) and 27% of mothers had no formal education. The average age of mothers of the deceased was 31 years. One-quarter of informants (29%) reported having no health insurance for the family. The leading COD was malaria (39%), then respiratory illness (14%) and acute abdomen (severe abdominal pain usually requiring surgery) at 14%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of paediatric autopsy cases in two rural districts of Rwanda, 2013–14

| Analytical sample n=77 | Full sample n=259 | |||

| Child mean age (years) | 2.5 | 2.6 | ||

| Maternal mean age (years) | 31.9 | 31.6 | ||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Child male | 44 | 57 | 148 | 57 |

| Mother with no formal education | 18 | 27 | 77 | 31 |

| Household >2 hours walking distance to facility | 31 | 41 | 100 | 39 |

| Household with no insurance coverage | 22 | 29 | 54 | 21 |

| Sought care from the formal health sector | 57 | 74 | 204 | 80 |

| Care provider* | ||||

| Traditional healer | 25 | 33 | 84 | 32 |

| Community health worker | 42 | 55 | 131 | 51 |

| Health centre | 47 | 61 | 164 | 63 |

| Hospital | 14 | 18 | 66 | 25 |

| First contact provider | ||||

| Community health worker | 35 | 46 | 104 | 48 |

| Health centre | 15 | 19 | 69 | 28 |

| Traditional healer | 9 | 12 | 30 | 14 |

| Private pharmacy | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Other | 16 | 21 | 53 | 20 |

| Site of death | ||||

| Home | 45 | 59 | 137 | 53 |

| Hospital | 7 | 9 | 46 | 18 |

| Health centre | 10 | 13 | 27 | 10 |

| Other | 15 | 20 | 49 | 19 |

| Causes of death | ||||

| Malaria | 30 | 39 | 101 | 39 |

| Acute abdomen | 11 | 14 | 25 | 10 |

| Acute respiratory infection, including pneumonia | 11 | 14 | 30 | 12 |

| Diarrhoeal disease | 6 | 8 | 13 | 5 |

| HIV/AIDS-related death | 6 | 8 | 32 | 12 |

| Accidental drowning | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Epilepsy | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Transport accident | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Other | 5 | 6 | 43 | 16 |

*May see multiple types of provider. The most likely cause of death was determined using InterVA4.27

Most children received some care from the formal health sector (FHS)—61% from a HC and 55% from a CHW. A CHW was the first point of contact for 46%. Nearly half of the caregivers (34 of 77) considered consulting a traditional healer during the illness leading to the index child’s death; 33% actually did. The majority (59%) of children died at home.

Phase I delays, were raised during 54 VSAs. Caregivers, most commonly mothers, frequently described ‘confusion’ and ‘surprise’ about their child’s illness and said that they did not know what to do or when to seek care. They also described domestic responsibilities that constrained the ability to closely monitor children. For example, as women worked on their farms, older children were left to tend younger children (table 2A).

Table 2.

Key themes and supporting excerpts

| Key theme | Excerpts |

| Phase I | |

| A. Constrained capacity to identify or understand illness |

|

| B. Traditional medicine |

|

| C. Pre-existing beliefs about the health system |

|

| Phase II | |

| D. Transportation challenges |

|

| Phase III | |

| E. Financial barriers at point-of-care |

|

| F. Poor quality of care |

|

| G. Positive experiences with FHS |

|

| Phase IV | |

| H. Dissatisfaction leads to traditional medicine |

|

| I. Home treatment plan failure |

|

The majority (63%, n=34) of VSA cases describing phase I delays also discussed traditional medicine (TM), primarily for the diagnosis of ‘poisoning’ which was described as being caused by ‘nasty people’ who wanted to do harm. The diagnosis was confirmed when a traditional healer successfuly indcued vomiting or diarrhoea with a liquid medication. Traditional healers were consulted either in conjunction with the FHS (medical pluralism) or exclusively. Some respondents reported using TM to ‘clear’ the poison so that the FHS could be effective; others tried all available options concurrently. Exclusive use of TM usually occurred if the caregiver was certain about the diagnosis of poisoning (table 2B).

The majority of this subgroup of respondents (19/34) indicated that only TM could treat poisoning. Beliefs and practices that were associated with exclusive use of TM for poisoning included ‘admitting’ severely ill children with poisoning to the house of a traditional healer and believing that FHS care for poisoned children, especially in the form of an injection, would kill the child (table 2B).

Previous experiences with the health system or CBHI (being rejected for lack of insurance or inability to pay out-of-pocket) shaped care-seeking decisions. Even those that did have CBHI experienced administrative challenges to maintaining coverage. Beliefs about the quality of the health system also informed decisions to seek care (table 2C).

Phase II delays were raised spontaneously by 4 of 77 informants. Transport barriers included drivers refusing critically ill children and cost (table 2D). Many informants mentioned waiting until morning to travel, but the safety of travelling at night was not discussed directly. These informants may be referring to phase II delays, but this cannot be determined from the narratives. Some informants mentioned bypassing the closest facility and going to one they believed would provide higher quality care.

Phase III delays were described in 57 of 77 (74%) cases. Despite Rwandan policy stating that no critically ill child should be turned away, five respondents reported being denied appropriate treatment in the FHS due to inability to pay (table 2E). Nearly all third-phase interviews mentioned poor quality of care (table 2F). A lack of FHS equipment, supplies, medicine or providers were reported by very few informants (n=6) and the majority of these excerpts related to CHWs. People describe ‘neglect’, being ‘ignored’, being ‘reprimanded’ or ‘shown contempt’. Long wait times were frequently mentioned. Leaving the FHS not knowing a child’s diagnosis or having a treatment plan, was common. Respondents reported poor provider technical skills at the FHS. Informants also described positive interactions with healthcare professionals who ‘immediately’ provided care or were empathic (table 2G), or went out of their way to help. Services were sometimes described as ‘good’ and ‘proper’.

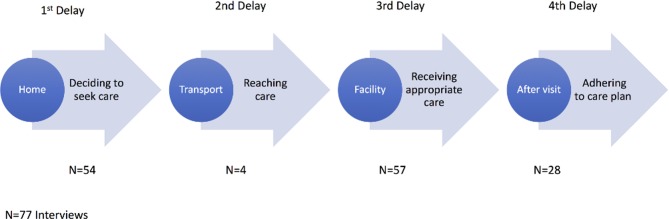

Informants reported barriers to successful care and treatment that did not fall into the three phases during 28 VSAs. These delays occurred after a child left the formal sector and were related to the willingness or capacity of caregivers to adhere to FHS treatment plans. We are calling these ‘phase IV delays’ (figure 1). Dissatisfaction with outcomes of care in the FHS (failed treatment or inconclusive tests) led families to abandon the formal sector and seek care from traditional healers (table 2H).

Figure 1.

Four phases of delay. The graphic illustrates four phases of delay, starting with the first delay in deciding to seek care. Once decisions to seek care have been made, phase II delays in reaching formal care may be experienced. Those who arrive at a facility may experience phase III delays in receiving timely and appropriate care. The fourth phase occurs after patients have left formal care and involves challenges in adhering to the prescribed care plan.

In seven cases, FHS personnel referred families to TM because poor treatment response was attributed to poisoning. Limited capacity to adhere to FHS treatment plans was linked to financial barriers or poor communication; caregivers lacked clear instructions on how to administer treatments or when to follow-up. Families were further challenged by needing to make multiple trips to FHS facilities (table 2I).

A hypothesis-driven mixed methods analysis revealed several additional themes. First, formal maternal education was associated with more active care-seeking language: "I decided", "I asked myself", "I had the child tested", "I suspected". Those without formal education disproportionately described delaying decisions in order to seek advice (table 3).

Table 3.

Phase I mixed methods themes and excerpts for maternal education

| No formal maternal education | Some formal maternal education | |

| Phase I excerpts by maternal education |

|

|

Second, children who died outside of a facility were not more likely to live far away from a HC or discuss phase II delays but were more likely to have died while caregivers were ‘preparing’ to go the FHS. This theme is not present in the subset of children that died in the FHS. Many caregivers of children who died at home actively made decisions to keep children at home if they believed that death was imminent; death at home appeared to be a preference. Those that did make it to a provider in the FHS but still had a child who died elsewhere, described issues with adherence to formal sector provider recommendations and follow-up; 88% of children whose caregivers discussed phase IV delays did not die in the FHS (table 4).

Table 4.

Phase I mixed methods themes and excerpts for place of death

| Did not die in a facility | Died in a facility | |

| Phase I excerpts by place of death |

|

Theme not present |

Finally, an analysis of excerpts by COD helped shed light on the fourth phase of delay (table 5). Although diversion to the informal sector occurred across all causes of death, the majority of cases of healthcare providers referring patients to traditional healers were in children who died of something other than malaria. Those who died of malaria had caregivers who described receiving ‘tablets’, waiting for them to take effect and having a child either die during treatment or in the care of a traditional healer because the treatments were perceived to be ineffective. They told of hesitating to take their child back to a facility despite recognising a lack of improvement during treatment. Whether this is because clear instructions for follow-up were not given or not understood cannot be determined from the data. Sometimes this hesitation came with an expressed fear of being judged for coming back too soon. Children without the diagnosis of malaria were less likely to have been given ‘tablets’ and more likely to experience delays after leaving an HC related to searching for a treatment from multiple formal facilities or from informal providers. Their decisions to seek alternatives were more likely to come immediately after leaving the treatment facility.

Table 5.

Phase IV mixed methods themes and excerpts for malaria diagnosis

| Malaria | Diagnosis other than malaria | |

| Phase IV excerpts by cause of death (COD) (malaria) |

|

|

| Phase III excerpts by COD domain | No divergent themes |

Discussion

We analysed VSAs of 77 children aged 1–5 years in rural Rwanda and found that care-seeking was dominated by challenges in deciding to seek care (phase I) and in receiving high-quality care in the FHS (phase III). Our respondents rarely mentioned challenges in reaching a facility (phase II), although it is unclear whether the common experience of waiting until morning to travel was related to difficulty securing transport. In addition to the three classic delays, we identified a domain that occurred after sick children visited the FHS; phase IV delays. These children were sent home after an interaction with the FHS only to experience delays in follow-up care or adherence to treatment.

Phase IV delays were related to caregiver dissatisfaction or inability to adhere to care plans and often involved decisions to abandon formal sector care in favour of traditional medicine. This phase was identified and characterised through the qualitative analysis of narratives and is supported by descriptive data showing that 74% of children in our dataset had contact with the FHS, but 59% died at home. Phase IV delays were closely linked to the ability of providers to communicate care plans and danger signs, a shortcoming that is particularly dangerous in the presence of a robust traditional medicine system that caregivers can turn to if interactions with formal care are unsatisfactory or if the child is not improving as expected. The most common COD in this sample, malaria, appeared to be associated with fourth phase delays caused by receiving treatment but not knowing when to return if treatment was not perceived to be effective.

The majority of deaths were not associated with a single delay (box 1). This finding is consistent with published literature on the three delays in maternal and child health.9 28 34 Families experienced complex care pathways that often began with partial information about child health and required the ability to negotiate competing explanatory models.35 Explanatory models are socioculturally informed systems that explain illness and healing; in this population, ‘poisoning’ appears to be a dominant construct. Those that did reach the FHS were sometimes turned away for financial reasons. Although some informants described positive experiences with the FHS, many did not. Children died while caregivers waited and families left facilities without knowing why their child was sick or when to return. They made decisions to use TM or visited many FHS facilities. The complexity of care navigation was particularly challenging for families who struggled with intersectional causes of disadvantage such as poverty and limited education.

Box 1. Illustrative care-seeking narrative.

In September, the child started having a cough and fever. And whenever the child had cough and fever, I rushed to CHWs who gave me tablets for the child. As the tablets did not help they finally referred me to the health facility…One of the health professionals I found there told me, " You have to take the child to your nearest health centre for TB test". And when I took the child to my nearest health centre, they did not perform TB test. The child became sickly such that I was obliged to go to the health facility every week.

When people saw that, they told me the child was victim of poisoning and asked me to take the child to those people who would pray for his recovery. When they told me that the child was suffering from poisoning, I took him/her to traditional healers who gave medications to the child. I spent there 2 weeks. After taking such medications, the child started having diarrhoea following which traditional healers told me, "The child has been poisoned". The traditional healers added, “As the child has started having diarrhoea after being given medications, it means that poison has been removed from the baby’s body. Now, you have to take the child to the health facility for him/her to be put on drip so that the level of water in his body can be increased".

I arrived [home] on a Saturday. On the following Monday, I said to myself, "I have to wash my clothes as I need to take the child to the health facility". However, the child’s hair had started becoming very fine as if the child had kwashiorkor. The CHW said to me, “The child appears to be in a critical condition and I have to give you a referral note so that you can take him/her to the health facility". The CHW reported that the child was suffering from malnutrition. However, I had adequate foods for my child. I had beans and often bought small fish commonly known as ‘ indagara’. I also used to buy soybeans and give the child porridge made up of a mixture of many ingredients. I had enough foods to feed my child.

As the child’s condition became very critical, I took the child to (HF X). And when I arrived there, a health professional rushed to call an ambulance on looking at the child…A health professional checked the palms of the child’s hands and his eyes and concluded that the child had anaemia. They immediately referred me to (HF Y).

I went to (HF Y) nearly 2 months after the child started having cough. Even if I used to take the child to those who would pray for him/her, I didn’t neglect seeking treatment from the health facility…I went to (HF Y) on the 26th day and stayed there for 23 days. This often happens when one is at the health facility. Whenever the child’s condition became critical, I went to alert them but they appeared not to be interested in what I was telling them. If they had taken care of the child, I wouldn’t have stayed for as many days at (HF Y)…At the end of these 23 days, they told me that I had to take the child to Kigali…When we arrived, they laid the child on the bed and was examined. The child lost weight. This is because when I took the child to the health facility for his 9- month vaccination, the child weighed 10 kg …The child weighed 3 kg at death. They then started feeding the child on milk…On the following Sunday, they stopped giving milk to the child and started feeding him/her on porridge…

However, there later came a time when the child’s condition started becoming very critical and the child would wake up every night crying out in pain…I went (back) to Kigali where they performed tests on the child and when I asked them, "What illness does the child have?", they turned a deaf ear to me. Around 7.00 one of the health professionals came to me and told me, “The child has little chance of survival. As you can see, the child is in a very critical condition. We’re very sorry for that". I too was realising that the child was going to die. I asked him/her, "What illness does the child have?" He/she told me that the child has pneumonia and that it was too late to save his life. It’s really unclear to me which of these illnesses killed the child (Parent of a boy aged 1.5 years who died of AIDS).

Minor changes to the narrative were necessary to make the order of health facilities clear to the reader.

A preference for dying at home, possibly due to indirect costs of facility death, may have contributed to the high percent of children who died at home (59%). Caregivers of children who died at home frequently described children dying while preparing to leave for the FHS suggesting that the urgency of the illness was not well understood. Finally, TM was used by one-third of families and even recommended by FHS providers possibly augmenting out-of-facility death rates. If poisoning was ‘confirmed’ (often when a traditional healer induced vomiting), some caregivers only used TM regardless of illness severity. Several practices made exclusive (rather than complementary) TM use more likely; several critically ill children in this sample were ‘admitted’ to the homes of traditional healers for more intense treatment and some informants believed that a poisoned child would be killed if treated in the FHS. This exclusive pattern of TM use is found in the literature on epilepsy and tuberculosis in Rwanda.36 37 Our data do not allow us to determine which symptoms are locally understood as indicative of poisoning in children, but according to Taylor (1988), the syndrome overlaps closely with features of clinical dehydration. Perhaps the non-specific nature of symptoms of poisoning contributes to the widespread use of TM in our study population.

Having TM as an alternative to shape an individual’s explanatory model35 was particularly important when caregivers were not satisfied with the care that they received at the FHS. A large portion of fourth phase delays involved abandoning FHS treatment plans in favour of TM. Limited literature is available on the nature or role of TM in Rwanda, due in part to only very recent efforts to recognise and integrate this sector into the health system (Government of Rwanda, 2012). A qualitative study of TM providers and their role in treating pregnant women estimated that there are up to two traditional providers in each village in Rwanda and that they are usually older women who inherited the profession from their mothers.38 Only one study was identified that specifically describes a Rwandan concept of poisoning.39 That work characterises poisoning as a humour that acts through the digestive tract and decreases blood volume, a description that seems largely consistent with our findings.

In addition to helping us understand care-seeking in the community, our data also describe a health system from the perspective of its users. Many informants consulted a CHW as a first source of care, as recommended by the RMOH model of primary care. This shows that the population accepts this cadre as an integral part of the Rwandan healthcare system. However, families also encountered problems with CHWs—the majority of reports about limited medications or human resources in our dataset were about CHWs. These issues might make CHWs a source of delay rather than an expansion of the healthcare web in Rwanda.

The experience of care at facilities is a significant challenge to informants in this dataset. These phase III themes are framed by the classic work on quality of care by Avedis Donabedian of structure/inputs, processes and outcomes.40 The procedural elements of care (both technical and interpersonal) are far more likely to be raised by our informants then the structure or inputs of the FHS. Our informants describe how this quality impacts decisions to seek care as well as how it impacts decisions to follow-through with treatment plans.

CBHI was widespread and highly valued by our informants. However, there were implementation challenges. Informants discuss the high cost of insurance and share deeply concerning narratives of being turned away from health facilities with critically ill children. Caregivers also describe avoiding health facilities because of a fear of being turned away due to not having health insurance.

As is the nature of qualitative research and despite census-level data, the themes arising from these data cannot be assumed to be representative beyond the population studied. However, our analysis of a large sample helps illuminate concepts that should be considered and explored in parallel populations. Other limitations include variation in interviewing techniques due to multiple research assistants in the field as well as variable transcription of narratives. We minimised this issue through rigorous training of our research assistants, and regular research team debriefings during data collection and processing. Although several techniques for triangulating and identifying cases were used, it is possible that child death cases were missed due to relocation or misclassification. This could lead to a selection bias because unidentified cases may be systematically different from those that were analysed (eg, more remote, fewer resources, less likely to seek care). Our community-based triangulation methods were designed to capture the most marginalised families and to identify those that have left the catchment area after a child’s death. Finally, our study is not powered to draw statistical conclusions from the descriptive data.

Conclusion

The patient narratives presented here describe the challenges that families face at home, in their communities and with the health system to provide their children with timely and appropriate medical care. Dramatic failures or gross indiscretions are rare. Parents and families describe making the decisions they thought were best and doing the most that they could despite barriers. The barriers and delays described by caregivers in this dataset are concentrated in the first and third phase, with a significant contribution from delays occurring after leaving a formal facility, a category of themes that we have termed phase IV delays. Using a four delays framework may help more fully characterise delays leading to the death of children in settings such as ours, because unlike maternal cases, definitive treatment for children often occurs after seeing a provider.

Rwanda has made exceptional progress in child health, meeting and exceeding MDGs. In order to maintain and accelerate this progress in the Sustainable Development Goals era, several approaches could be considered. Healthcare service delivery needs to be consistently and reliably aligned with national policies and would require improved facility-level accountability mechanisms to ensure that patients are not denied care or otherwise treated unfairly. Continued improvements in the quality of care, especially around provider competence in the areas of patient-centred care and communication, are necessary. Provider competencies should include the ability to form healing partnerships with patients to prevent poor adherence and the ability to explore and understand competing explanatory models that may cause delays in achieving good health outcomes.41 Finally, in order for caregivers to be partners in child health, they must have practical knowledge about appropriate care-seeking and be empowered to use it to help their children be healthy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the data collectors and study staff for their dedication to collect the data with great sensitivity and compassion for the families involved in this study. The authors would like to thank hospital leadership and staff from Rwinkwavu and Kirehe District Hospitals and the many health workers who have committed their lives to caring for families in Rwanda. The authors would like to thank Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102) via mixed methods consulting services from Rebekka M Lee. (The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.) The authors would like to thank the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation’s African Health Initiative funding for this project. The authors would also like to thank the families and caregivers who generously shared their difficult stories to contribute to reducing U5 mortality in Rwanda.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study oversight (LRH, NG), study design (LRH, NG, DMK, LH), data collection (LH, DMK), data coding (LH, SR-D), data analysis (SR-D, LRH), manuscript writing (SR-D), manuscript review (SR-D, NG, LH, DMK, EN, CM, TB, LRH).

Funding: This study was funded by Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Study approval was received from the Rwanda National Ethics Committee and Partners Health Care.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Musafili A, Essén B, Baribwira C, et al. Trends and social differentials in child mortality in Rwanda 1990-2010: results from three demographic and health surveys. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:834–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. LÅ P, Rahman A, Peña R, et al. Child survival revolutions revisited – lessons learned from Bangladesh, Nicaragua, Rwanda and Vietnam. 2017:871–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. UNICEF. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet 2016;388:3027–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. UNICEF. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2015. Estimates Developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bojalil R, Kirkwood BR, Bobak M, et al. The relative contribution of case management and inadequate care-seeking behaviour to childhood deaths from diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections in Hidalgo, Mexico. Trop Med Int Health 2007;12:1545–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Waiswa P, Kallander K, Peterson S, et al. Using the three delays model to understand why newborn babies die in eastern Uganda. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:964–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noordam AC, Carvajal-Velez L, Sharkey AB, et al. Care seeking behaviour for children with suspected pneumonia in countries in sub-Saharan Africa with high pneumonia mortality. PLoS One 2015;10 :1932-6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ingabire CM, Kateera F, Hakizimana E, et al. Determinants of prompt and adequate care among presumed malaria cases in a community in eastern Rwanda: a cross sectional study. Malar J 2016;15:227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bensaïd K, Yaroh AG, Kalter HD, et al. Verbal/Social Autopsy in Niger 2012-2013: A new tool for a better understanding of the neonatal and child mortality situation. J Glob Health 2016;6:010602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Manzi A, Magge H, Hedt-Gauthier BL, et al. Clinical mentorship to improve pediatric quality of care at the health centers in rural Rwanda: a qualitative study of perceptions and acceptability of health care workers. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moh R. Republic of Rwanda: Health System, 2014. http://gov.rw/services/health-system/2016.

- 13. Mugeni C, Levine AC, Munyaneza RM, et al. Nationwide implementation of integrated community case management of childhood illness in Rwanda. Glob Health Sci Pract 2014;2:328–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitsunaga T, Hedt-Gauthier BL, Ngizwenayo E, et al. Data for program management: An accuracy assessment of data collected in household registers by community health workers in Southern Kayonza, Rwanda. J Community Health 2015;40:625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Makaka A, Breen S, Binagwaho A. Universal health coverage in Rwanda: a report of innovations to increase enrolment in community-based health insurance. The Lancet 2012;380:S7. [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Institute of Statistics of R, Ministry of F, Economic PR, Ministry of HR, International ICF. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2014-15: Kigali, Rwanda: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning/Rwanda, Ministry of Health/Rwanda, and ICF International, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nonyane BA, Kazmi N, Koffi AK, et al. Factors associated with delay in care-seeking for fatal neonatal illness in the Sylhet district of Bangladesh: results from a verbal and social autopsy study. J Glob Health 2016;6:010605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koffi AK, Maina A, Yaroh AG, et al. Social determinants of child mortality in Niger: Results from the 2012 National Verbal and Social Autopsy Study. J Glob Health 2016;6:010603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kalter HD, Yaroh AG, Maina A, et al. Verbal/social autopsy study helps explain the lack of decrease in neonatal mortality in Niger, 2007–2010. Journal of Global Health;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Njuki R, Kimani J, Obare F, et al. Using verbal and social autopsies to explore health-seeking behaviour among HIV-positive women in Kenya: a retrospective study. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koffi Alain K, Babille M, Salgado R, et al. Social autopsy for maternal and child deaths: a comprehensive literature review to examine the concept and the development of the method. Population Health Metrics 2011;9:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. D’Ambruoso L, Byass P, Qomariyah SN, et al. A lost cause? Extending verbal autopsy to investigate biomedical and socio-cultural causes of maternal death in Burkina Faso and Indonesia. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1728–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hildenwall H, Tomson G, Kaija J, et al. "I never had the money for blood testing" - caretakers' experiences of care-seeking for fatal childhood fevers in rural Uganda - a mixed methods study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2008;8:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalter HD, Salgado R, Babille M, et al. Social autopsy for maternal and child deaths: a comprehensive literature review to examine the concept and the development of the method. Popul Health Metr 2011;9:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bentley B, O’Connor M. Conducting research interviews with bereaved family carers: when do we ask? J Palliat Med 2015;18:241–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dwyer SC, Jackson M. Qualitative bereavement research: incongruity between the perspectives of participants and research ethics boards AU - Buckle, Jennifer L. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2010;13:111–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Verbal autopsy standards: The 2012 WHO verbal autopsy instrument Release Candidate 1. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health, Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1091–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kruk ME, et al. High quality health systems—time for a revolution: Report of the Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems in the SDG Era Lancet Global Health, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maxwell JA. Qualitative research design: an interactive approach. 3rd ed Thousand Oaks: Calif, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Creswell J. A Concise Introduction To Mixed Methods Research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Curry L-S. Mixed Methods in Health Sciences Research: A Practical Primer. Applications and Illustrations of Mixed Methods Health Sciences Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018;52:1893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Påfs J, Musafili A, Binder-Finnema P, et al. Beyond the numbers of maternal near-miss in Rwanda - a qualitative study on women’s perspectives on access and experiences of care in early and late stage of pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med 1978;88:251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Finel E. Fighting Against Epilepsy in Rwanda: An Efficient Patient Centred Experience, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ngang PN, Ntaganira J, Kalk A, et al. Perceptions and beliefs about cough and tuberculosis and implications for TB control in rural Rwanda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007;11:1108–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beste J, Asanti D, Sirotin N, et al. Traditional Medicine Use in Pregnancy in Rural Rwanda, 2012:S846–S7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Taylor CC. The concept of flow in Rwandan popular medicine. Soc Sci Med 1988;27:1343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988;260:1743–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: the problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med 2006;3:e294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.