Abstract

Introduction

In many developed nations, including Australia, a substantial number of children aged under 5 years attend centre-based childcare services that require parents to pack food in lunchboxes. These lunchboxes often contain excessive amounts of unhealthy (‘discretionary’) foods. This study aims to assess the impact of a mobile health (m-health) intervention on reducing the packing of discretionary foods in children’s childcare lunchboxes.

Methods and analysis

A cluster randomised controlled trial will be undertaken with parents from 18 centre-based childcare services in the Hunter New England region of New South Wales, Australia. Services will be randomised to receive either a 4-month m-health intervention called ‘SWAP IT Childcare’ or usual care. The development of the intervention was informed by the Behaviour Change Wheel model and will consist primarily of the provision of targeted information, lunchbox food guidelines and website links addressing parent barriers to packing healthy lunchboxes delivered through push notifications via an existing app used by childcare services to communicate with parents and carers. The primary outcomes of the trial will be energy (kilojoules) from discretionary foods packed in lunchboxes and the total energy (kilojoules), saturated fat (grams), total and added sugars (grams) and sodium (milligrams) from all foods packed in lunchboxes. Outcomes will be assessed by weighing and photographing all lunchbox food items at baseline and at the end of the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the Hunter New England Local Health District Human Ethics Committee (06/07/26/4.04) and ratified by the University of Newcastle, Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2008–0343). Evaluation and process data collected as part of the study will be disseminated in peer-reviewed publications and local, national and international presentations and will form part of PhD student theses.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12618000133235; Pre-results.

Keywords: lunchbox, discretionary foods, m-health, childcare

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This randomised controlled trial is the first to use an m-health intervention to reduce packing of unhealthy foods in lunchboxes in centre-based childcare services.

The study uses rigorous outcome measures consisting of weighed food records, supplemented by food photography.

The intervention is developed using a systematic theory-based approach to identify strategies to target parental barriers to packing healthy lunchboxes.

If found to be effective, the intervention has potential to be delivered via other childcare online technology-based communication platforms.

The intervention is conducted in one region of Australia which may limit the generalisability of the study findings.

Introduction

Poor dietary behaviours are leading modifiable risk factors for the development of future chronic disease including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and certain cancers.1 2 To reduce chronic disease risk, it is recommended that the intake of discretionary foods (ie, foods high in energy, saturated fat, sugar and/or sodium) is limited.1 Excessive intake of discretionary foods in childhood is linked to conditions such as dental caries,3 altered lipid profiles4 and unhealthy weight gain.5 Given that dietary preferences established in childhood are known to track into adulthood,6 efforts to decrease the consumption of discretionary foods in the early childhood years are recommended to reduce the burden of chronic disease.1

National dietary guidelines recommended that children up to 8 years of age consume no more than 0.5 serves of discretionary foods per day unless the child is taller or more active where they may consume up to two serves per day (ie, no more than 300–1200 kJ per day from discretionary foods).7 Despite this, population studies indicate that child consumption typically exceeds these recommendations.8–10 Specifically, in Australia children aged 4–8 years consumed an average of 41% of their daily energy intake from discretionary foods, the equivalent to approximately 4.5 serves.8

Centre-based childcare services, such as preschools and long day care centres, have been identified as priority settings for interventions to improve child diet.11–13 Such services provide access to a significant number of children, with upwards of 80% of children attending some form of centre-based care in the year prior to compulsory schooling in Australia, the UK and USA.14–16 As children can consume between one-third to two-thirds of their daily food intake while in centre-based childcare,17 achieving even modest dietary improvements in this setting is likely to have considerable potential to improve child health.

In Australia, the UK and the USA, it is estimated that between 30% and 50% of centre-based childcare services require parents to pack food in a lunchbox for their children to consume while in care.14 15 18 Evidence suggests, however, that children’s lunchboxes contain excessive amounts of discretionary foods. For example, a study of Australian children attending 29 centre-based childcare services found that 60% of lunchboxes contained more than one serve of discretionary food, with an average of two serves of discretionary foods provided per lunchbox. In addition, 38% of lunchboxes were considered poorly balanced containing more than one serve of discretionary food and lacked vegetables, fruit or a healthy main meal.19 An additional study conducted in 30 centre-based childcare services in Texas, USA, (607 children) similarly found a disproportionate amount of discretionary foods packed in lunchboxes with contents exceeding recommendations for saturated fat, sugar and sodium.20

Despite the potential to improve child diet via interventions to reduce packing of discretionary foods in lunchboxes of children attending centre-based childcare, to our knowledge just three randomised trials have been conducted,21–23 with only one reporting on impact on child dietary intake.24 Two of these trials used multicomponent service-based strategies including staff nutrition training and child education, alongside parent targeted strategies (including workshops and parent activity stations).21 22 Both trials reported significant improvements in the packing of discretionary foods. The remaining trial involved training of childcare staff without any direct parent strategies. This trial was ineffective in reducing packing of discretionary foods.23 While these findings suggest that interventions targeting parents are more likely to have an impact, previous approaches have been time and resource intensive, requiring parents to attend face-to-face educational sessions. Such strategies have been reported to have limited reach,25 and reduce the potential for intervention delivery at a population level.

Using mobile technology to directly reach parents has been suggested as a potentially effective strategy to overcome the limited reach of previous parent targeted interventions.26 27 Evidence demonstrates that mobile health (m-health) interventions can be effective in changing dietary behaviours in both adults28 and children.28 29 The use of mobile phone applications (apps) has been identified as highly acceptable to parents as a preferred health engagement tool,30 and has the potential to successfully reach the large majority (over 86%) of parents who are estimated to now own a smart phone.31 Embedding interventions within existing childcare service mobile phone apps may also overcome previously reported barriers related to reach and engagement via their ability to reach parents at any place or time, deliver education materials and provide reminders or prompts targeting specific behaviours.27 Using an existing school communication app for the purpose of delivering healthy lunchbox information to parents was found to be highly feasible and acceptable by principals in the primary school setting within the Hunter New England (HNE) region of NSW,32 and the results of a healthy lunchbox pilot study using this model showed promising effects on the nutritional quality of children’s lunchbox contents (unpublished data from a randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness, feasibility and acceptability of an m-health intervention ‘SWAP IT’, provided by author RS, 2018). Using a similar approach in the centre-based childcare setting to reduce the packing of discretionary foods in lunchboxes therefore appears highly feasible. Despite this, to the author’s knowledge, no such m-health intervention has been conducted in this setting.

Study aims

The primary aim of the trial is to assess the efficacy of an m-health intervention, embedded within an existing childcare parent communication app to reduce (i) the mean energy (kJ) from discretionary foods and drinks packed in children’s lunchboxes, and (ii) the mean energy (kJ), saturated fat (g), total and added sugars (g) and sodium (mg) from all foods and drinks packed in lunchboxes. We will also assess the impact of the intervention on child dietary consumption of (i) mean energy (kJ) from discretionary foods packed in the lunchbox; (ii) mean energy (kJ), mean saturated fat (g), sodium (mg) and total and added sugars (g) from all foods and drinks packed in the lunchbox; (iii) serves of lunchbox discretionary foods and drinks packed and consumed and (iv) usual serves of discretionary foods consumed over 24 hours. Parent and service acceptability and feasibility and potential adverse effects of the intervention will also be assessed.

Methods and analysis

Settings and design

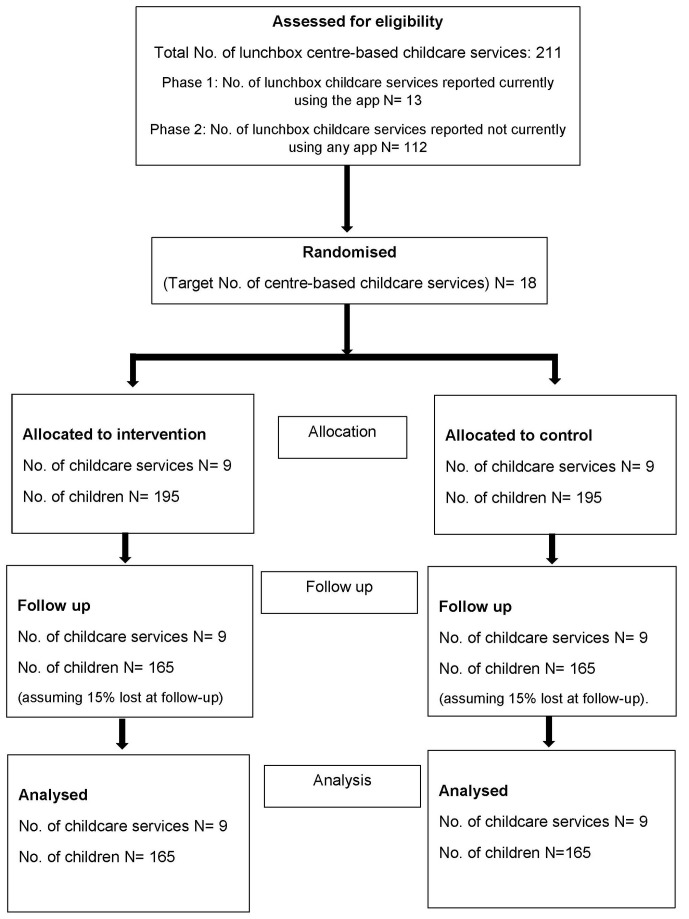

The study will use a cluster randomised controlled trial design, and will be conducted with parents and children attending centre-based childcare services located in the HNE Local Health District of New South Wales (NSW), Australia (see figure 1). Allocation will be at the unit of the childcare service. In 2016, approximately 819 814 people were reported to reside in the HNE area, of which 51 900 were children aged 0–4 years.33 The area encompasses major metropolitan centres and inner regional communities, with a small percentage (14%) of people located in remote communities.34

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram estimating the progress of centre-based childcare services and children through the trial.

The trial will run between March 2018 and January 2019. Following baseline data collection services will be randomly allocated to receive the approximately 4-month intervention or to a usual care control group. The trial outcome measures will be assessed in the same child cohort within both groups at baseline and postintervention. The study will follow the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials reporting guidelines.35

Participants and eligibility

Sample

A list of all centre-based childcare services (including long day care and preschool services) located in the study region will be accessed via the NSW Ministry of Health. Approximately 211 (54%) services in the study region require parents to pack foods (referred to as lunchbox services) and will serve as the sampling frame. Within NSW, long day care services can provide centre-based care for children from 6 weeks to under 6 years of age for 8 or more hours per day. Preschools typically enrol children between 3 and 6 years of age and provide care for 6 and 8 hours per day.36

Eligibility

To be eligible to participate, lunchbox services must cater for children 3–6 years of age, and be either existing users of the designated parent communication app (Skoolbag),37 or have a willingness to commence using the app. Services will be excluded if they are participating in any other trial related to improving child nutrition, cater exclusively for children with special needs or are a Department of Education community run service (as they are not covered within the existing ethics arrangement). Parents or carers (hereafter referred to as ‘parents’) of children aged 3–6 years will be eligible to participate if their child attends during the days of data collection period and if they indicated willingness to download or use the app. Children will be excluded if they have special dietary requirements or allergies that would necessitate specialised tailoring of their diet.

Recruitment procedures

Services

Initial recruitment will target eligible services currently using Skoolbag (n=13), after which services that do not use any app (as identified via a telephone survey undertaken by the research team) will be randomly approached (n=112) until 18 services are enrolled in the trial. Services commencing using the app for the purpose of the trial will be able to use the app free of charge for the duration of the intervention.

Service managers of eligible services will be posted and emailed information statements and consent forms detailing the study and requesting participation. Written consent to participate in the trial will be provided by the manager on behalf of the services.

Children

Centre-based childcare staff will distribute hard copies of information statements and consent forms to parents approximately 2 weeks prior to baseline data collection. To maximise consent rates, research assistants will also be present at the service for 2 days (based on highest child attendance) during drop off and pick up times to speak with eligible parents and promote participation in the trial. If more than one child is eligible per family, only the oldest will be included in the trial to reduce participant burden.

Random allocation of childcare services

Consenting services will be randomly allocated to the intervention or usual care control group in a 1:1 ratio using a computerised random number generator. Randomisation of services will be undertaken following baseline data collection by a statistician who will otherwise have no involvement in the study. Based on evidence of associations for family socioeconomic status and rurality with child dietary intake,38 39 randomisation will be stratified by the socioeconomic area of the childcare service and by rural location. As part of ensuring equity of access to the intervention, services will also be stratified by those with high numbers of Aboriginal child enrolments defined as those with >10% Aboriginal children enrolled. This level of stratification was deemed appropriate for the sample size.40

This trial will be conducted as an open trial due to the nature of the intervention. Services and parents will be notified of their allocation following baseline data collection; however, outcome assessors will remain blinded to service allocation.

Sample size and power calculations

The study aims to recruit approximately 390 children from 18 childcare services. Given a 15% attrition rate at follow-up, this will allow detection of a mean difference of 123 kJ in the primary outcome, with an alpha of 0.01 (adjusting for multiple outcomes), and an estimated intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.1, with 80% power41 42 and a SD of 200 kJ. The ICC applied is based on internal and unpublished pilot data undertaken with a smaller number of lunchboxes. As children are recruited from childcare centres which may have existing lunchbox policies that may impact on provision of food, we anticipate that an ICC of 0.1 may be a conservative estimate of clustering. Approximately, 123 kJ difference in energy was considered clinically significant based on an estimate of the energy deficit required to reduce the prevalence of childhood obesity (420 KJ)43 and proportionally adjusted to the amount of time children spend in care (approximately one-third of the day). Such an energy reduction could be expected to result in the detection of approximately 0.6 g less saturated fat, 2.2 g less sugar and 44 mg less sodium.8

Intervention

‘SWAP IT Childcare’ is an adapted version of a previously piloted intervention conducted with primary school children aged 5–12 years. The programme is embedded in an existing parent communication app used in both schools and centre-based childcare services and aims to assist parents to ‘swap in’ healthy foods and ‘swap out’ discretionary foods when packing lunchboxes. Services use this communication app to provide information to parents regarding their child’s daily activities, newsletters and other service-related information. The app has the capacity to deliver content in the form of text, images and media (videos) and store information available for permanent access.

The programme was coproduced by a team of behavioural researchers, public health nutritionist, centre-based childcare staff and the technology provider ‘Skoolbag’ and was based on formative evaluations with parents. Key differences between the primary schools and childcare settings as well as parent reported barriers were identified during formative assessments which necessitated amendments to strategy selection, intervention components and content between the two programmes. The ‘SWAP IT Childcare’ intervention will specifically target parents of children aged 3–6 years and will be primarily delivered via a series of push notification messages using the service’s communication app. Feedback was sought on the content of the programme from parents of childcare-aged children, the research unit’s Aboriginal Health Staff advisory group and from two local Aboriginal centre-based childcare service managers to ensure cultural appropriateness.

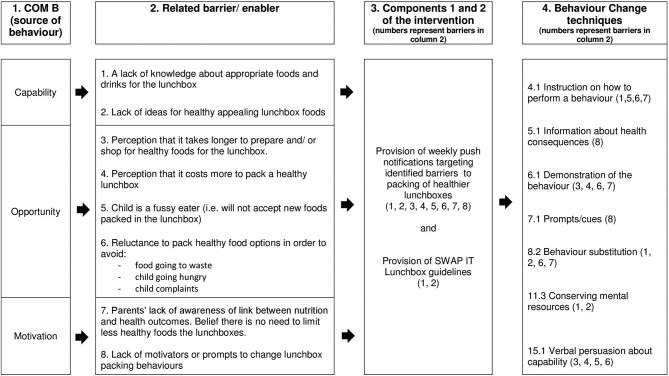

Application of a theoretical framework

The ‘SWAP IT Childcare’ intervention content was developed using the Behaviour Change Wheel.44 This theoretically driven framework is based on 19 theories of health behaviour and is designed to enable the systematic development of interventions for supporting behaviour change.44 For a description of the application of the framework, please refer to online supplementary file 1. An overview of the intervention mapping process is provided in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Intervention mapping overview.

bmjopen-2018-026829supp001.pdf (397.4KB, pdf)

Intervention strategies

A 4-month intervention (table 1) consisting of the following components will be delivered as part of ‘SWAP IT Childcare’.

Table 1.

Intervention components, strategies and resources

| Intervention component | Strategy description | Resources and delivery mode |

| 1. Provision of weekly push notifications targeting identified barriers to the packing of healthier lunchboxes | Push notifications will alert parents to messages sent via the service’s app for 10 weeks (1 per week). The behaviour change techniques designed to influence parent behaviour will be delivered via the content of these messages and images, and through attachments and links to the ‘SWAP IT Childcare’ webpages, videos, fact sheets and other websites. Graphics of recommended ‘swaps’ will be included in various messages, for example a graphic recommending a swap from a popular high saturated fat, high sodium savoury cracker to low saturated fat, lower sodium cracker, a swap from a cheese flavoured biscuit to vegetables sticks and dip and a swap from chocolate biscuit snacks to wholegrain cereal snacks. As an example of a push notification message, the message aiming to reduce the perceived barrier of ‘cost of a healthy lunchbox’, includes persuasive language explaining that expensive foods does not need to be purchased to provide a healthy lunchbox. It also includes an embedded video in the push notification message that provides examples of inexpensive healthy foods to pack for children, and will demonstrate how healthy items often cost the same as less healthy items in the supermarket. Finally, an attached fact sheet provides practical examples of how to save money and demonstrates cost savings possible over a year. For further information on behaviour change techniques used to address each barrier, please refer to figure 2. | (a) ‘SWAP IT Childcare’ push notification topics delivered via the app Week 1 (2 messages): Welcome to ‘SWAP IT’ The ultimate list of healthy lunchbox foods Week 2: ‘Sweet’ food ideas for the lunchbox Week 3: Cost saving ideas for the lunchbox Week 4: Common fussy eating concerns Week 5: Healthy savoury snacks that are a hit! Week 6: Why are some lunchbox snacks better than others? Week 7: Is your child drinking enough? Week 8: Top five time saving ideas when packing a healthy lunchbox Week 9: Supporting children to try new foods Week 10: Thanks for being part of SWAP IT (b) Links to fact sheets and videos within messages Top time saving tips (fact sheet and video) Money saving tips for the lunchbox (fact sheet and video) Fussy eating concerns (fact sheet) Tips for encouraging new foods (fact sheet and video) Five best savoury swaps for the lunchbox (fact sheet) Five best sweet swaps for the lunchbox (fact sheet) |

| 2. Provision of ‘SWAP IT Options’ lunchbox guidelines | Parents will be given access to and encouraged to use service-endorsed ‘SWAP IT Options’ lunchbox guidelines recommending which foods and drinks to ‘swap from’ and which to ‘swap to’ when packing a healthy lunchbox. The guidelines were developed by dietitians and provide specific guidance in line with the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating,7 recommendations outlined in the NSW Ministry of Health nutrition sector specific resource57 and health and well-being requirements outlined in national accreditation standards.58 | (a) ‘SWAP IT Options’ lunchbox guidelines, provided via links in push notification messages delivered via the app SWAP IT Options Savoury SWAP IT Options Sweet SWAP IT Options Lunch foods SWAP IT Options Drinks |

| 3. Centre-based childcare service endorsement of the programme | To support service adoption of the ‘SWAP IT Choices’ lunchbox guidelines, a Health Promotion Officer will conduct a brief onsite visit with the service manager to familiarise them with the guidelines and provide support to integrate these with existing service lunchbox policies (if required). The Service Managers will also be asked to communicate their endorsement of the intervention and guidelines to Educators via a staff meeting or individual briefings and provide hard copies of the SWAP IT messages and the SWAP IT Lunchbox guidelines. Service managers will be asked to send two communications to parents via the app or other preferred communication methods (eg, hard copy newsletters). The first communication will be sent prior to the first app push notification message to convey service support for the programme, and to endorse the use of the ‘SWAP IT Options’ lunchbox guidelines and the second communication, will be sent approximately midintervention. This is designed to provide parents with non-contingent praise and support to continue to access the app and its content and assist with prevention of a drop off in opening messages over time. A record of implementation will be given to service managers to enable them to record their delivery of the agreed tasks during the intervention period and to measure implementation fidelity. |

(a) Health Promotion Officer Service visit and provision of hard copies of resources prior to commencement of push notification messages. (b) Service-delivered communication to parents prior to commencement of push notifications and provision of sample message template to the service. (c) Service-delivered communication to parents midway through push notification delivery period and provision of sample message template and (week 5). (d) Provision of a service-completed record of implementation form. |

Provision of weekly push notifications targeting identified barriers to the packing of healthier lunchboxes.

Provision of ‘SWAP IT Options’ which are centre-based childcare lunchbox guidelines designed to provide specific information to parents on suitable foods for the lunchbox.

Centre-based childcare service endorsement of the programme in order to support adoption of the ‘SWAP IT Options’ lunchbox guidelines.

Further details regarding each strategy and delivery mode are provided in table 1.

Control group

Services allocated to the control group will participate in data collection only. Parents from these services will receive routine centre-based childcare communication via the app (usual care) with no access to the lunchbox content.

Patient and public involvement

The research question and intervention was codesigned together with the local health promotion unit (HNE Population Health) responsible for supporting childcare services to support parents with packing healthier lunchboxes. As described in the methods, intervention design and content was informed in part, by the results of a survey of parents (n=29) from a convenience sample of local childcare services and consultation with two local Aboriginal centre-based childcare service managers. Service managers were also consulted about the acceptability of app technology for delivering the intervention to parents. The participating parents were not involved in the design, recruitment or conduct of the study; however, childcare staff will support recruitment via assistance with distribution and collection of consent forms and assistance with the data collection process by identifying lunchboxes for weighing. Participant burden to engaging with the intervention will be assessed as part of a follow-up survey with parents assessing acceptability and time and cost of changing behaviours. A summary of the results will be provided to participating services to distribute to parents and a copy of the summary will be available on the research unit’s website or on individual request from parents.

Data collection procedures and measures

Primary outcomes

Food packed in lunchboxes

The primary trial outcomes include mean energy (kJ) provided by discretionary foods, and mean energy (kJ), saturated fat (g), total and added sugars (g) and sodium (mg) provided by all food and drinks packed in children’s lunchboxes. The outcome will be assessed via photography and weighed food records. Weighing is considered as one of the most accurate methods of determining portion size and consumption of food and drinks.45 Research assistants will undertake a 1-day training session requiring them to practice weighing sample lunchboxes and complete data collection forms with feedback given on their adherence to data collection protocols. Lunchbox measures will be undertaken on 1 unique day for each child as part of 2-day data collection at each service at both baseline and approximately 4 months follow-up. The days of the week on which data will be collected may be different for each service. Parents will not be informed of the day that lunchbox data will be collected to minimise reactivity bias. On the days of data collection, all packed food and drinks (excluding water) will be weighed, individually where possible, and photographed by a trained research assistant blinded to service allocation. Food will be photographed against paper that includes a metric ruler graphic to aid weight estimations if required. Weight will be recorded in grams by a second trained research assistant using a standardised form developed by the research team. To ensure consistency and quality of data collection, lunchbox photographs and data collection forms will be reviewed by a dietitian once returned for accuracy and compliance with protocols.

The weighed food record data will be verified using photos and entered into a food and nutrient analysis database (Foodworks)46 in grams by a trained dietitian. The weights of individual foods weighed as part of a mixed foods (eg, determining the weight of the cheese and weight of the bread as part of the total grams recorded for a cheese sandwich) will be estimated by using standard weights from Foodworks foods if applicable (eg, a standard weight of a slice of bread) or estimates extrapolated by visual assessment of photographs. Where foods are home-made, an appropriate standard recipe will be sourced from within the Foodworks database. Where a suitable recipe is not available, dietitians within the research team will reach a consensus on an appropriate alternate source for the recipe. When commercial foods are not in their packages, photographs will be used in conjunction with the research team’s consensus on the most likely product fit and these assumptions will be recorded. A random sample of approximately 20% of lunchbox data entries will be checked for errors by a second dietitian following the same data entry protocols and corrections made as required.

Secondary outcomes

Child dietary consumption of foods packed in lunchboxes

Children’s consumption of mean energy (kJ) from discretionary foods, and mean energy (kJ) saturated fat (g), total and added sugars (g) and sodium (mg) from all foods and calorific drinks packed in children’s lunchboxes will be assessed. As per the packed lunchbox contents, consumption will be measured on the same unique day for each child at both baseline and approximately 4 months follow-up. On the day of the lunchbox audits, as part of the data collection procedure, children will be asked to return all uneaten food and empty packaging to their lunchbox. After the final meal of the day, food weights, and any packaging included as part of preconsumption weights, will be weighed and recorded in grams on the same data collection form. In order to determine amounts consumed, the total weight of the foods/drinks post consumption will be subtracted from the total weight of food/drinks preconsumption. The same process (as described for the primary outcome measure) will be undertaken when entering the amount of food consumed into Foodworks for the nutrient analysis. This method of collecting preconsumption and postconsumption weighed food records has been successfully undertaken by the research team as part of a previous trial conducted with 26 childcare services.47

Serves of lunchbox discretionary foods packed and consumed

The number (count of individual items) and serves (600 kJ equivalents) of discretionary food and drinks packed and consumed will be reported. A dietitian will categorise each item as discretionary or non-discretionary consistent with the Australian Dietary Guidelines.7

Overall daily usual child intake of discretionary foods

Overall daily usual child intake of discretionary foods (serves per day) will be measured via a subgroup of questions included as part of a 65-item food frequency questionnaire. This will be completed as part of the online parent survey by both intervention and control parents at baseline and follow-up.

The food frequency questions were sourced from the Short Food Survey, which has been found to be a valid and reliable tool for Australian children aged 4–11 years with a significant correlation (r=0.43–0.44, p<0.01) reported for serves of discretionary foods against 24 hours recalls.48 Minor adaptations to the survey were made to capture foods frequently served in the centre-based childcare setting.

The online parent survey will be emailed to consenting parents after the completion of service-level baseline data collection and again at follow-up. Parents will be asked to complete the survey for their oldest eligible child only. If not completed, an automated email reminder will be sent after approximately 2 weeks. After a further week, non-responders will be offered the opportunity to complete the survey via phone interview or via paper form.

Other measures

Parent and child demographics

Parent and child demographic information will be collected as part of the parent online survey and via participant consent form. Specifically, parents will report on child age, gender, postcode of residence and parental education level, as part of the consent form, and additional questions on income level, living arrangements and language spoken at home will be collected via the online survey.

Service operational characteristics

Service operational characteristics will be assessed via a pen and paper survey completed by the service manager at all participating services at baseline on 1 day of service data collection. Characteristics will include number of years in operation, total number of children enrolled, number of staff employed and previous staff nutrition training.

Service nutrition context (staff behaviours and service nutrition policy and procedures)

The service nutrition context will include assessments of nutrition policies and staff behaviours (eg, prompting children to eat healthy food, role modelling healthy eating, meal time practices) where there is evidence of potential impact of behaviours on food packed and consumed by children in care. An adapted version of an existing tool, the Environment and Policy Assessment Observation (EPAO) instrument will be used to assess nutrition context.49 Modified versions of the EPAO have been used previously by the research team in other intervention trials.50–52 Completion of the EPAO will be undertaken by a third trained research assistant on 1 of the 2 days allocated for service-level data collection. A research assistant will observe service staff present in the room/space where the majority of eligible children are present throughout the day between the core hours of 9 am to 3 pm. The EPAO tool also includes a short in-person service manager interview to collect information and documentation of service nutrition policies and procedures.

Cost and time

Total grocery cost and average time spent in packing lunchboxes will be assessed via items included in the online parent survey at baseline and postintervention for both intervention and control groups. Change in mean cost of lunchbox contents will be assessed using prices as indicated from online supermarket websites using quantities extracted from weighted lunchbox records at baseline and follow-up.

Adverse events

To monitor any adverse parent reaction as a result of the intervention, the average number of parent complaints regarding lunchbox policies at each service will be determined via a question included in the service manager pen and paper survey in intervention and control services at both baseline and follow-up.

Intervention acceptability and feasibility

Within the intervention services, parent acceptability (ie, an assessment as to whether the intervention is agreeable or satisfactory) will include assessing satisfaction and perceived usefulness of the programme content and delivery via items included within the parent survey.53 Feasibility (ie, suitability for use) will include measuring parent use and engagement with the intervention, through the use of app and programme website analytics data including: number of message views, frequency of click throughs to linked web-based resources and number of website page views.53 Additional information related to parent engagement will be collected in the parent online survey via 25 items assessing use of the app and features such as the push notification alerts, satisfaction and usefulness of the programme, number of messages opened, number of links accessed and any barriers to accessing or using the technology. At follow-up service, acceptability will include assessment of service managers satisfaction, perceived usefulness and appropriateness of the programme measured via a separate 22-item pen and paper survey adapted from an existing questionnaire.54

Intervention fidelity

Intervention fidelity will include assessing whether messages were delivered as intended and quality of message content via researchers directly monitoring the push notifications during the intervention. Parent exposure to the intervention will be assessed via questions included in the parent online survey. Service delivered components of the intervention will be measured via a service completed implementation log. Implementation of other intervention components, for example site visits conducted as planned, will be recorded as part of the research team’s project records. Measuring fidelity across various domains such as these has been recommended as key to informing ‘real-world uptake’ of interventions.55

Contamination and cointervention measures

Contamination will be largely mitigated by centrally controlled access to the intervention (ie, only parents of the intervention services will receive the messages via the app). Within the postintervention survey, parents will be asked if they accessed the intervention or study website in the last 4 months. Service and parent receipt of other nutrition interventions separate to the trial during the invention period will be assessed via questions included within the EPAO document and within the parent survey at follow-up.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis will be performed with SAS V.9.4 statistical software by an experienced statistician independent to the study. Differences in outcomes between groups will be assessed using hierarchical linear regression models, adjusting for prespecified prognostic variables associated with the outcome (service level EPAO scores), as well as clustering, controlling for baseline outcome. A subgroup analyses by child gender and socioeconomic status will also be undertaken to assess whether there was a differential impact according to such variables. Using intention to treat principles,56 missing data from primary and secondary outcomes at follow-up due to attrition, will be imputed using multiple imputation56 through the SAS MI and MIANALYZE Procedure and will be the main analyses. Findings from the complete case analyses will also be reported. An additional outcome analysis will be conducted whereby only parents who have downloaded the app will be included.

Discussion

This randomised controlled trial is the first to assess the impact of an m-health intervention targeting the packing of discretionary foods in lunchboxes in the childcare setting. It significantly adds to the limited evidence available for interventions that aim to successfully engage parents and improve centre-based childcare lunchboxes with high potential for delivery at scale. The use of technology to directly support parents packing behaviours represents a highly innovative approach to improve the diets of young children attending centre-based childcare services.

The research also has the potential to significantly improve the health outcomes of young children. The benefits of reducing discretionary foods include a likely improvement in diet quality, potentially facilitating risk factor reduction for conditions such as type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease and certain cancers later in life.8 If shown to be effective, this intervention has the potential to be embedded into other m-health or childcare online technology-based communication platforms providing an opportunity to reach parents nationally to improve the health of young children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank members of the Good for Kids. Good for Life team (Hunter New England Population Health), the Population Health Aboriginal Advisory Network Group, Christophe Lecathelinais (Statistician) and local contributing Childcare services and parents of participating centre-based childcare services.

Footnotes

Contributors: First author NP led the development of this manuscript. MF, NP, SLY, RS, NN, LW and VH led the development of the intervention. MF, NP, SLY, RS, NN, AG, MK and KG contributed to the evaluation protocol and research design. MF, NP, SLY, RS, NN, LW, AG, MK, KG and VH contributed to drafting and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Infrastructure funding was provided in kind by Hunter New England Population Health. Dr Meghan Finch is a clinical research fellow funded by Hunter New England Population Health and the Health Research and Translation Center, Partnerships, Innovation and Research, Hunter New England Local Health District. Dr Sze Lin Yoong receives salary support via an ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE170100382). Open access publication costs are partially funded by the Faculty of Health, University of Newcastle as part of research support provided to Dr Yoong. Dr Rachel Sutherland and Dr Melanie Kingsland are supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Translating Research into Practice Fellowship. Associate Professor Luke Wolfenden receives salary support from an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (grant ID: APP1128348) and Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (grant ID: 101175). Dr Nicole Nathan is supported by NHMRC Translating Research Into Practice Fellow, Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellow and Sir Winston Churchill Fellow. The contents of this manuscript are the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of the NHMRC.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval has been provided by the Hunter New England Local Health District Human Ethics Committee (06/07/26/4.04) and ratified by the University of Newcastle, Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2008-0343). The trial is prospectively registered with the Australian New Zealand clinical trials registry (ACTRN12618000133235p). Evaluation and process data collected as part of the study will be disseminated peer-reviewed publications and local, national and international presentations, and will form part of a PhD student thesis.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation on Diet, Nutrition and the prevention of Chronic Disease. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Disease: report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation, in WHO technical report series; 916. Geneva, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2016. Australia’s health series no. 15. Cat. no. AUS 199. Canberra: AIHW, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organisation. Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: Summary report. Pediatrics 2011;128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kumar S, Kelly AS. Review of childhood obesity: From epidemiology, etiology, and comorbidities to clinical assessment and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;92:251–65. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mura Paroche M, Caton SJ, Vereijken C, et al. How infants and young children learn about food: A systematic review. Front Psychol 2017;8:1046 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Health and Medical Research Council. Educator Guide, p22. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson BJ, Bell LK, Zarnowiecki D, et al. Contribution of Discretionary Foods and Drinks to Australian Children’s Intake of Energy, Saturated Fat, Added Sugars and Salt. Children 2017;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Public Health England, National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Results from Years 5-6 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2012/13 – 2013/14). London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drewnowski A, Rehm CD. Consumption of added sugars among US children and adults by food purchase location and food source. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:901–7. 10.3945/ajcn.114.089458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buscemi J, Odoms-Young A, Stolley ML, et al. Adaptation and dissemination of an evidence-based obesity prevention intervention: design of a comparative effectiveness trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2014;38:355–60. 10.1016/j.cct.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larson N, Ward DS, Neelon SB, et al. What role can child-care settings play in obesity prevention? A review of the evidence and call for research efforts. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:1343–62. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mikkelsen MV, Husby S, Skov LR, et al. A systematic review of types of healthy eating interventions in preschools. Nutr J 2014;13:56 10.1186/1475-2891-13-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lucas PJ, Patterson E, Sacks G, et al. Preschool and School Meal Policies: An Overview of What We Know about Regulation, Implementation, and Impact on Diet in the UK, Sweden, and Australia. Nutrients 2017;9:736 10.3390/nu9070736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sweitzer SJ, Briley ME, Robert-Gray C. Do sack lunches provided by parents meet the nutritional needs of young children who attend child care?. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:141–4. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Australian Government Australian Institute of Family Studies. Child care and early childhood education in Australia. 2015. https://aifs.gov.au/publications/child-care-and-early-childhood-education-australia (Accessed: 20 Sep 2018).

- 17. Soanes R, Miller M, Begley A. Nutrient intakes of two- and three-year-old children: a comparison between those attending and not attending long day care centres. Nutr Diet 2001;58:114–20. [Google Scholar]

- 18. NSW Ministry of Health, Population Health Information Management System (PHIMS).Healthy Children Initiative; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kelly B, Hardy LL, Howlett S, et al. Opening up Australian preschoolers' lunchboxes. Aust N Z J Public Health 2010;34:288–92. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Romo-Palafox MJ, Ranjit N, Sweitzer SJ, et al. Adequacy of parent-packed lunches and preschooler’s consumption compared to dietary reference intake recommendations. J Am Coll Nutr 2017;36:169–76. 10.1080/07315724.2016.1240634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roberts-Gray C, Briley ME, Ranjit N, et al. Efficacy of the Lunch is in the Bag intervention to increase parents' packing of healthy bag lunches for young children: a cluster-randomized trial in early care and education centers. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016. 3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zask A, Adams JK, Brooks LO, et al. Tooty Fruity Vegie: an obesity prevention intervention evaluation in Australian preschools. Health Promot J Austr 2012;23:10–15. 10.1071/HE12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hardy LL, King L, Kelly B, et al. Munch and Move: evaluation of a preschool healthy eating and movement skill program. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2010;7:80 10.1186/1479-5868-7-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts-Gray C, Ranjit N, Sweitzer SJ, et al. Parent packs, child eats: Surprising results of Lunch is in the Bag’s efficacy trial. Appetite 2018;121:249–62. 10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roberts-Gray C, Sweitzer SJ, Ranjit N, et al. Structuring Process Evaluation to Forecast Use and Sustainability of an Intervention: Theory and Data From the Efficacy Trial for Lunch Is in the Bag . Health Educ Behav 2017;44:559–69. 10.1177/1090198116676470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mitchell GL, Farrow C, Haycraft E, et al. Parental influences on children’s eating behaviour and characteristics of successful parent-focussed interventions. Appetite 2013;60:85–94. 10.1016/j.appet.2012.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Curtis KE, Lahiri S, Brown KE. Targeting Parents for Childhood Weight Management: Development of a Theory-Driven and User-Centered Healthy Eating App. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e69 10.2196/mhealth.3857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:127 10.1186/s12966-016-0454-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rose T, Barker M, Maria Jacob C, et al. A systematic review of digital interventions for improving the diet and physical activity behaviors of adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2017;61:669–77. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fjeldsoe BS, Miller YD, O’Brien JL, et al. Iterative development of MobileMums: a physical activity intervention for women with young children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:151 10.1186/1479-5868-9-151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yellow Social Media Report 2018 Consumers. Yellow Social Media Report 2018- Consumers. Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reynolds R, Sutherland R, Nathan N, et al. Feasibility and principal acceptability of school-based mobile communication applications to disseminate healthy lunchbox messages to parents. Health Promot J Austr (Published Online First: 12 March 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population Health and Housing-Community Profiles. 2016. 2018. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/Home/2016%20Census%20Community%20Profiles.

- 34.NSW Health website. 2018. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/lhd/pages/hnelhd.aspx

- 35. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:834–40. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4240.0 Preschool Education, Australia. Canberra, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Skoolbag PTY LTD,. MOQ group of companies. Skoolbag 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Burns CM, Gibbon P, Boak R, et al. Food cost and availability in a rural setting in Australia. Rural Remote Health 2004;4:311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ward PR, Coveney J, Verity F, et al. Cost and affordability of healthy food in rural South Australia. Rural Remote Health 2012;12:12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kang M, Ragan BG, Park JH. Issues in outcomes research: an overview of randomization techniques for clinical trials. J Athl Train 2008;43:215–21. 10.4085/1062-6050-43.2.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Delaney T, Wyse R, Yoong SL, et al. Cluster randomized controlled trial of a consumer behavior intervention to improve healthy food purchases from online canteens. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:ajcn158329–20. 10.3945/ajcn.117.158329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yoong SL, Grady A, Wiggers J, et al. A randomised controlled trial of an online menu planning intervention to improve childcare service adherence to dietary guidelines: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017498 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cochrane T, Davey R, de Castella FR. Estimates of the energy deficit required to reverse the trend in childhood obesity in Australian schoolchildren. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016;40:62–7. 10.1111/1753-6405.12474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ward S, Blanger M, Donovan D, et al. Association between childcare educators' practices and preschoolers' physical activity and dietary intake: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013657 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xyris software. Foodworks. High Gate Hill: QLD, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Seward K, Wolfenden L, Finch M, et al. Multistrategy childcare-based intervention to improve compliance with nutrition guidelines versus usual care in long day care services: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010786 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hendrie GA, Viner Smith E, Golley RK. The reliability and relative validity of a diet index score for 4-11-year-old children derived from a parent-reported short food survey. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:1486–97. 10.1017/S1368980013001778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ward D, Hales D, Haverly K. An instrument to assess the obesogenic environement of child care centers. Am J Health Beha 2008;32:380–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Finch M, Wolfenden L, Falkiner M, et al. Impact of a population based intervention to increase the adoption of multiple physical activity practices in centre based childcare services: a quasi experimental, effectiveness study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9:101 10.1186/1479-5868-9-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Razak LA, Yoong SL, Wiggers J, et al. Impact of scheduling multiple outdoor free-play periods in childcare on child moderate-to-vigorous physical activity: a cluster randomised trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2018;15:34 10.1186/s12966-018-0665-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bell AC, Davies L, Finch M, et al. An implementation intervention to encourage healthy eating in centre-based child-care services: impact of the Good for Kids Good for Life programme. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:1610–9. 10.1017/S1368980013003364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci 2017;12:108 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Taki S, Lymer S, Russell CG, et al. Assessing user engagement of an mhealth intervention: development and implementation of the growing healthy app engagement index. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e89 10.2196/mhealth.7236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Breitenstein SM, Fogg L, Garvey C, et al. Measuring implementation fidelity in a community-based parenting intervention. Nurs Res 2010;59:158–65. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dbb2e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. White IR, Horton NJ, Carpenter J, et al. Strategy for intention to treat analysis in randomised trials with missing outcome data. BMJ 2011;342:d40 10.1136/bmj.d40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. NSW Ministry of Health. Caring for Children birth to 5 years. Sydney: NSW Government, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority. What is the NQF? 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026829supp001.pdf (397.4KB, pdf)