Abstract

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common chronic respiratory disease. It has adverse effects on patients’ physical health, mental well-being and quality of life. The purpose of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) is to raise non-judgemental awareness and attention to current internal and external experiences. This means the attention is shifted from perceived and involuntary inner activities to current experience, keeping more curious, open and accepting attitudes towards current experience. Although some studies on the intervention effect of MBIs in patients with COPD have been conducted, the results are controversial, especially on dyspnoea, level of mindfulness and quality of life. Therefore, a systematic review of MBIs in patients with COPD is required to provide available evidence for further study.

Methods and analysis

In this study, different studies from various databases will be involved. Randomised controlled trials(RCTs)/quantitative studies, qualitative studies and case studies on the effect of MBIs in patients with COPD aged over 18 years will be included. We will search the literature in the databases of PubMed, Excepta Medica Base (EMBASE), Web of Science, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Cochrane Library, PsycINFO and China National Knowledge Infrastructure(CNKI). The primary outcomes will include efficacy of MBIs for patients with COPD in terms of dyspnoea, depression and anxiety. The secondary outcomes will include efficacy of MBIs in terms of quality of life, mindful awareness, 6-minute walk test(6MWT) and nutritional risk index. Data extraction will be conducted by two researchers independently, and risk of bias of the meta-analysis will be evaluated based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. All data analysis will be conducted by data statistics software Review Manager V.5.3. and Stata V.12.0.

Ethics and dissemination

Since this study is a systematic review, the findings are based on the published evidence. Therefore, examination and agreement by the ethics committee are not required in this study. We intend to publish the study results in a journal or conference presentations.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018102323.

Keywords: chronic airways disease, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides a detailed and evidence-based study on the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Extensive search strategies and inclusion criteria will be included in this study, indicating a comprehensive narrative of the available evidence.

Data extraction and risk of bias of studies involved in the meta-analysis will be conducted independently.

Sensitivity and subgroup analysis will be used to explore the source of heterogeneity for the meta-analysis, and the potential publication bias will be assessed by funnel plot combined with Egger’s regression test.

Although detailed retrieval strategies have been formulated in our study, unpublished trials may not be included.

Introduction

As a common disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterised by persistent and progressive limitation of airflow, accompanied by an increase in chronic inflammatory responses caused by harmful particles or gases in the airways and lungs. Besides this, the acute exacerbation and comorbidities affect the overall severity of this disease.1 Due to the high mortality, COPD endangers patients’ health and lives, placing a heavy financial burden on their families and society.2

It is reported that the worldwide incidence of COPD is about 10%.3 COPD might jump from the fourth to the third cause of death globally by 2020, ranking fifth in the global economic burden.4 An epidemiological survey of COPD in China shows that the prevalence rate of COPD is 8.2% for people older than 40 years, the numbers of deaths and disabled due to COPD are more than 1 million and 5~10 million a year, respectively.5 In rural areas, the mortality rate of respiratory diseases ranks first among all causes of death in China.6

COPD has a serious impact on patients’ physical health, mental well-being and life. General adverse physiological effects are mainly manifested in skeletal muscle consumption and dysfunction, weight loss, cardiovascular complications, malnutrition and change in body composition.7–9 With decreased amount of activity, the muscle strength and resistance of the patient’s body are gradually weakened, and symptoms of dyspnoea become more serious. Thus, a vicious cycle is formed, that is breathing difficulty to activity reduction to dyspnoea aggravation, finally resulting in accelerated deterioration of physical condition.10 11 Besides, mood disorders are common symptoms among patients with COPD. In recent years, studies have confirmed that anxiety and depression are the most common and most easily overlooked complications in patients with COPD.12–14 Anxiety and depression can affect the mental and physical health. They are associated with activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which may impair immune function and increase susceptibility to respiratory tract infections and COPD exacerbations.15 Anxiety and depression patients tend to have low self-confidence or self-efficacy, which may lead to poor disease-related coping ability and self-care behaviors. That is to say, they are unwilling to carry out lung rehabilitation, reduce the physical activity, encounter the smoking cessation failure, form poor dietary habits and poor drug compliance. Then the progression of COPD exacerbations is accelerated. In the end, the number of acute exacerbations, hospitalisation frequency and time are increased with greater disability and dyspnoea.15 16 Quality of life is a key indicator for estimating disease burden, especially for chronic diseases.17 Research has shown that patients with COPD may have poor quality of life.17 18 Depressive symptoms negatively influence quality of mental life, and dyspnoea often interferes with health-related quality of life.18 19

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are usually referred to as short interventions (generally eight courses) provided in a group environment, including mindfulness meditation exercises and principles.20 The purpose of MBIs is to raise non-judgemental awareness and attention towards current internal and external experiences. That is, attention is drawn away from perceived and involuntary inner activities to current experience, with more curious, open and accepting attitudes towards current experience.21–23 Present mindfulness interventions include mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and brief mindfulness meditation training intervention.24 There are other MBIs also, that include mindfulness training exercises as part of the treatment programme, such as acceptance and commitment therapy, compassion-focused therapy, dialectical behaviour therapy, integrative body-mind training and cognitive behavioural stress management.24 25These methods have proved beneficial to patients.24 25

It has been proved that MBIs can reduce symptoms of chronic disease and improve accurate symptom assessment, which may improve disease management and well-being in patients with COPD.26 A phenomenological study has verified that MBCT can benefit patients with asthma and COPD suffering to anxiety and depression by the following qualitative data, including the combination of lung rehabilitation advice with mindfulness; greater acceptance and reduction of disease-related stigma; a new relationship development between breathing, activity and related thoughts; the notice of subtle physical sensations and early signs of difficulty breathing; being creative with limitations and removing mental barriers to become more active; having a stronger sense of control.27

It is verified that MBIs are effective in improving mindful awareness, CD3+ T cell number, CD4+ T cell number28 and depression,29 reducing the nutritional risk index and CD8+ T cell number in patients with COPD.28 Compared with the only used systematic health education intervention, systematic health education combined with MBIs can lower dyspnoea and nutritional risk index, and improve mindful awareness.30 A 10-minute MBI in patients with COPD has shown a changing tendency in the outcomes of the intervention group, including depression, anxiety, happiness, dyspnoea, mindfulness and stress. While no significant difference exists among groups, most participants supposed that the mindfulness interventions were useful and were glad to recommend it.16 It is concluded that meditation may improve detection ability, monitor immediate ventilatory needs and respiratory load, improve mental acuity, promote patients' active participation in daily life activities, and achieve better self-care management of disease for anxious patients with COPD.31–33 MBSR has been proved to improve the quality of life of veterans with chemical lung injury, but not their lung function.34 However, compared with the support group, no significant improvement has been observed in exacerbation rates of the randomised controlled trial (RCT), the health-related quality of life measures, mindfulness, 6-minute walk test (6MWT) distance, dyspnoea, stress or symptom scores for patients with COPD after receiving mindfulness-based breathing therapy.35

In 2016, a systematic review was conducted to examine the effect of mindfulness on mindful awareness, health-related quality of life and stress in adults with respiratory illnesses. In this meta-analysis, three studies proposed that mindfulness cannot improve health-related quality of life, while two studies claimed that mindfulness cannot improve the level of mindfulness and relieve stress. Different conclusions are largely due to inconsistent research methodologies.36 In the former study of adult respiratory diagnosis published in 2016, three outcomes were obtained for the MBSR intervention. In this paper, patients with COPD with different types of MBIs and more outcomes are investigated. Considering the small number of eligible studies, we intend to involve RCTs/quantitative studies, qualitative studies and case studies in this study to describe the application status of MBIs in patients with COPD. Besides, meta-analysis should be only performed on the basis of RCTs.

The updated systematic review and meta-analysis is performed for two objectives: (1) To describe the application status of MBIs delivered for patients with COPD. (2) To examine the effect of MBIs on outcomes including dyspnoea, depression, anxiety, quality of life, mindful awareness, 6MWT and nutritional risk index.

Methods and analysis

Study registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis protocol have been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews(PROSPERO). The protocol has strictly been reported according to the requirements of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P).37

Inclusion criteria for study selection

Types of included studies

We intend to perform quantitative studies, qualitative studies and case studies in this systematic review to describe the application status of MBIs in patients with COPD. All RCTs evaluating the efficacy of MBIs in patients with COPD will also be included in this study. There will be no restrictions on the language and time of publication. Animal mechanism studies, RCT protocol and duplicate publications will be excluded. It should be noted that duplicate publication refers to an article substantially overlapping with another published one in print or electronic media.38

Participants

Patients aged at least 18 years old with a clinical diagnosis of COPD confirmed by postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) <80% of the predicted value in combination with a FEV1% (FEV1/FVC (forced vital capacity)) <70% in accordance with the global initiative for COPD,39 the American Thoracic Society, the British Thoracic Society, the European Respiratory Society or Chinese COPD guideline. 40

Intervention

The study aims at the efficacy of MBIs in patients with COPD. Thus, different types of MBIs should be covered, including MBSR, MBCT, acceptance and commitment therapy, brief mindfulness meditation training interventions, cognitive behavioural stress management, dialectical behaviour therapy, integrated body-mind training and compassion focused therapy, and so on. The intervention measures taken by the experimental group must be MBIs or MBIs with other combined treatment methods. The control group receives different treatment from the experimental group, such as the systematic health education, healthy living course, support group consisting of semi-structured conversations about the disease and scheduling daily diaries for patients. Otherwise, no intervention is performed in control group, namely the wait-list control group.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes will include the MBIs' efficacy for patients with COPD in terms of dyspnoea based on scales such as the modified Medical Research Council Scale30and the Borg Dyspnoea Scale,35 depression and anxiety evaluated by a scale such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.16 The secondary outcomes will include evaluation of quality of life (based on the MOS 36-item Short Form Health Survey(SF-36)Questionnaire34 and the Saint George Respiratory Questionnaire35), mindful awareness (based on the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale16 and the 5-Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire35), 6MWT (based on the Borg Dyspnoea Scale35) and nutritional risk index (based on the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 Scale28 30).

Search strategy

We intend to perform a literature search from PubMed, Web of Science, Excepta Medica Base (EMBASE), the Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO and China National Knowledge Infrastructure(CNKI) in accordance with database rules. During literature retrieval, information experts and lung disease experts have offered help and guidance. To fully retrieve eligible studies, a comprehensive retrieval strategy will be adopted, combing with medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, text words, titles/abstracts and synonyms. These detailed search strategies for different databases are shown in online supplementary appendix A.

bmjopen-2018-026061supp001.pdf (148.9KB, pdf)

Data collection and analysis

Studies selection

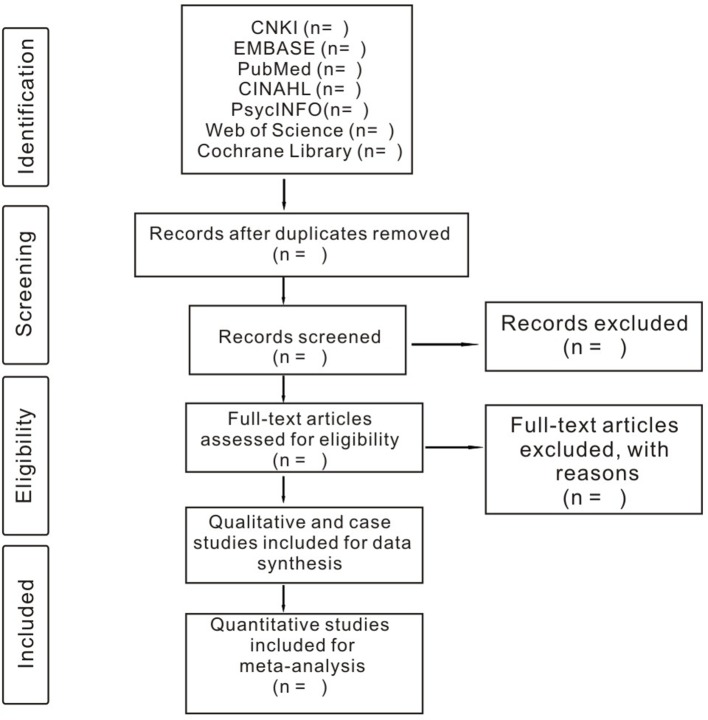

The selection of research literature will be independently carried out by two researchers. First, we will make a preliminary selection by reading the abstract and title. Second, we will download all relevant studies for further selection according to the inclusion criteria. If there is a difference of opinion between two researchers, the issue will be discussed to reach an agreement. If it fails to reach a consensus through discussion, the third researcher will make the final decision. The selection process is displayed in the PRISMA flow chart (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of studies identified.

Data extraction

We will explore the characteristics of different studies qualitatively. Two researchers are responsible for data extraction. The main extraction content includes the publication time, authors, region, participants (n, gender and age), study design, intervention methods, intervention duration, outcomes, assessment method, significant findings and duration of follow-up. If two researchers have different opinions and do not reach a consensus through discussion, the third researcher will make the final decision.

Risk of bias assessment

To evaluate risk of bias in the meta-analysis, all studies involved in the meta-analysis will be evaluated based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.41 Assessment items will involve random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias. If there are different opinions, the third researcher will make the final decision.

Statistical analysis

We will conduct data analysis using data statistics software Review Manager V.5.3. and Stata V.12.0. Continuous variables will be analysed by mean difference or standardised mean difference with 95% CIs, and classified variables will be analysed by risk ratio (RR) or OR with 95% CIs. When extracting raw data from studies, we will estimate RR in longitudinal, cohort and cross-sectional studies and OR in case-control studies.42 We will use the random effects model to conduct the meta-analysis based on research recommendations.43 Heterogeneity will be calculated based on the X2 test, and the judgement of degree of heterogeneity will depend on the value of I2 (I2>50% or not) or p value (p<0.10 or not).44 We will use sensitivity and subgroup analysis to explore the source of heterogeneity. The following subgroup analysis will be performed on different types of MBIs (eg, MBSR, MBCT, acceptance commitment therapy, meditation, dialectical behaviour therapy, cognitive behavioural stress management, etc), types of patients, intervention duration and duration of follow-up. The potential publication bias of all used studies in the meta-analysis will be assessed by funnel plot combined with Egger’s regression test.

Patient and public involvement

This study is a meta-analysis using data from previously published studies, hence patients and the general public were not involved in this study.

Discussion

This study aims to systematically review the efficacy of MBIs in patients with COPD. It will provide a detailed and evidence-based overview of the effect of MBIs on improving dysponea, depression, anxiety, quality of life, mindful awareness, 6MWT and nutritional risk index of patients with COPD. Results of this study will provide the evidence base to clinical practitioners for selecting mindfulness-based therapies for patients with COPD, and offer patients with appropriate personalised interventions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: T-LY is responsible for the writing of the entire manuscript. The electronic database retrieval strategy is formulated by T-LY and ZY. LL and WY will independently screen the research, extract the needed research data and assess the bias risk. If LL and WY fail to reach an agreement in the above process, the final decision will be made by L-YL. The statistical analysis will be done by T-LY.

Funding: This work is supported by Hunan Provincial Development and Reform Commission (Project Grant No. [2016]65) and Hunan Provincial Social Science Foundation (Project Grant No.14YBA404).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Cheng Y, Han X, Luo Y, et al. Analysis of co-morbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for patients in Yangpu District of Shanghai. Journal of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Medical Science 2015;35:82–5. 96. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu W, Zx G, Li B. Study on traditional Chinese medicine constitution types of patients with Acute Exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) with secondary pulmonary fungal infections and prevention and treatment. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae 2013;19:321–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Menezes AM, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JR, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence study. Lancet 2005;366:1875–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67632-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Mathers CD, et al. The Global Burden of Disease 2000 project: aims, methods and data sources (GPE Discussion Paper No. 36), 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:753–60. 10.1164/rccm.200612-1749OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qian GS. Efforts on improving the diagnosis and treatment of respiratory diseases in China. Chinese Journal of lung disease 2015;5:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pitta F, Troosters T, Spruit MA, et al. Characteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:972–7. 10.1164/rccm.200407-855OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shrikrishna D, Patel M, Tanner RJ, et al. Quadriceps wasting and physical inactivity in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1115–22. 10.1183/09031936.00170111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Osthoff AK, Taeymans J, Kool J, et al. Association between peripheral muscle strength and daily physical activity in patients with COPD: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2013;33:351–9. 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reardon JZ, Lareau SC, ZuWallack R. Functional status and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 2006;119:32–7. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. ZuWallack R. How are you doing? What are you doing? Differing perspectives in the assessment of individuals with COPD. COPD 2007;4:293–7. 10.1080/15412550701480620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jx L, Qiu XM, Cw W. Correlation between BODE index of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and anxiety depression symptoms. Journal of Clinical Pulmonary Medicine 2016;21:460–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maurer J, Rebbapragada V, Borson S, et al. Anxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needs. Chest 2008;134:43S 10.1378/chest.08-0342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Norwood R. Prevalence and impact of depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2006;12:113–7. 10.1097/01.mcp.0000208450.50231.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laurin C, Moullec G, Bacon SL, et al. Impact of anxiety and depression on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:918–23. 10.1164/rccm.201105-0939PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perkins-Porras L, Riaz M, Okekunle A, et al. Feasibility study to assess the effect of a brief mindfulness intervention for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Chron Respir Dis 2018;15:400–10. 10.1177/1479972318766140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pengpid S, Peltzer K. The impact of chronic diseases on the quality of life of primary care patients in Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam. Iran J Public Health 2018;47:1308–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ivziku D, Clari M, Piredda M, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and caregivers: an actor-partner interdependence model analysis. Qual Life Res 2019;28:461–72. 10.1007/s11136-018-2024-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ries AL. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on quality of life: the role of dyspnea. Am J Med 2006;119:12–20. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of an anxiety or depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 2014;9:e96110 10.1371/journal.pone.0096110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003;84:822–48. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Williams JM, Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces overgeneral autobiographical memory in formerly depressed patients. J Abnorm Psychol 2000;109:150–5. 10.1037/0021-843X.109.1.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, et al. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2010;11:230–41. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Creswell JD. Mindfulness interventions. Annu Rev Psychol 2017;68:491–516. 10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Craig C, Hiskey S, Royan L, et al. Compassion focused therapy for people with dementia: a feasibility study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018;33:1727–35. 10.1002/gps.4977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chan RR, Giardino N, Larson JL. A pilot study: mindfulness meditation intervention in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:445–54. 10.2147/COPD.S73864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Malpass A, Kessler D, Sharp D, et al. MBCT for patients with respiratory conditions who experience anxiety and depression: a qualitative study. Mindfulness 2015;6:1181–91. 10.1007/s12671-014-0370-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jn L, Guo X, Wang HY. Application of mindfulness intervention in health education on patients with pulmonary tuberculosis complicated with COPD. Chinese Nursing Research 2015;29:2983–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Panagioti M, Scott C, Blakemore A, et al. Overview of the prevalence, impact, and management of depression and anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:1289–306. 10.2147/COPD.S72073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang DM. Effect of systematic health education combined with mindfulness behavior nursing intervention on pulmonary tuberculosis patients with COPD. Laboratory Medicine and Clinic 2017;14:1819–21. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim YY, Choi JM, Kim SY, et al. Changes in EEG of children during brain respiration-training. Am J Chin Med 2002;30:405–17. 10.1142/S0192415X02000272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chan AS, Han YM, Cheung MC. Electroencephalographic (EEG) measurements of mindfulness-based triarchic body-pathway relaxation technique: a pilot study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2008;33:39–47. 10.1007/s10484-008-9050-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lutz A, Greischar LL, Rawlings NB, et al. Long-term meditators self-induce high-amplitude gamma synchrony during mental practice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:16369–73. 10.1073/pnas.0407401101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arefnasab Z, Ghanei M, Noorbala AA, et al. Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on quality of life (SF-36) and spirometry parameters, in chemically pulmonary injured veterans. Iran J Public Health 2013;42:1026–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mularski RA, Munjas BA, Lorenz KA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based therapy for dyspnea in chronic obstructive lung disease. J Altern Complement Med 2009;15:1083–90. 10.1089/acm.2009.0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harrison SL, Lee A, Janaudis-Ferreira T, et al. Mindfulness in people with a respiratory diagnosis: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:348–55. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;350:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Choi WS, Song SW, Ock SM, et al. Duplicate publication of articles used in meta-analysis in Korea. Springerplus 2014;3:182–7. 10.1186/2193-1801-3-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: GOLD. 2016. http://www.goldcopd.org [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40. Group of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, branch of respiratory diseases, and Chinese medical association. Guidance of diagnosis and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (reversed edition in 2007). Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis 2007;30:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0: the cochrane collaboration, 2011. Available at http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/cochrane-handbook-for-systematic-reviews-of-interventions-version-5-1-0/ [Google Scholar]

- 42. Simou E, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Alcohol and the risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022344 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, et al. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine 2009;34:1929–41. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026061supp001.pdf (148.9KB, pdf)