Abstract

Introduction

Migrants without residency permit, known as undocumented, tend to live in precarious conditions and be exposed to an accumulation of adverse determinants of health. Only scarce evidence exists on the social, economic and living conditions-related factors influencing their health status and well-being. No study has assessed the impact of legal status regularisation. The Parchemins study is the first prospective, mixed-methods study aiming at measuring the impact on health and well-being of a regularisation policy on undocumented migrants in Europe.

Methods and analysis

The Parchemins study will compare self-rated health and satisfaction with life in a group of adult undocumented migrants who qualify for applying for a residency permit (intervention group) with a group of undocumented migrants who lack one or more eligibility criteria for regularisation (control group) in Geneva Canton, Switzerland. Asylum seekers are not included in this study. The total sample will include 400 participants. Data collection will consist of standardised questionnaires complemented by semidirected interviews in a subsample (n=38) of migrants qualifying for regularisation. The baseline data will be collected just before or during the regularisation, and participants will subsequently be followed up yearly for 3 years. The quantitative part will explore variables about health (ie, health status, occupational health, health-seeking behaviours, access to care, healthcare utilisation), well-being (measured by satisfaction with different dimensions of life), living conditions (ie, employment, accommodation, social support) and economic situation (income, expenditures). Several confounders including sociodemographic characteristics and migration history will be collected. The qualitative part will explore longitudinally the experience of change in legal status at individual and family levels.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Geneva, Switzerland. All participants provided informed consent. Results will be shared with undocumented migrants and disseminated in scientific journals and conferences. Fully anonymised data will be available to researchers.

Keywords: undocumented migrant, migration, health, wellbeing, regularization, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The prospective and mixed-methods approaches will allow generation of a comprehensive understanding of the factors operating across time on health and well-being.

The qualitative part will provide further insights into individual and family experiences in parting with their undocumented status and facing the new challenges that regularisation entails.

The main limitation will be the risk of attrition in the control group considering the harsh and unpredictable living context of such migrants.

The study is designed to minimise such risk by selecting undocumented migrants having a relatively stable personal situation.

Introduction

Undocumented or irregular migration is defined as ‘movements that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving countries’.1 It results from overstaying after temporary residency permit expiration, asylum claim refusal or entering the country without valid migration documentation.1 2 In the absence of valid methods of identification, the figures provided for undocumented migrants are mainly theoretical and estimated by cross-referencing different sources. Recent valid data are generally lacking. The International Organization for Migration estimated that there were 20–30 million undocumented migrants worldwide in 2010.3 According to the Pew Hispanic Center, the number of undocumented migrants from Latin America in the USA increased from 8.4 in 2000 to 11.1 million in 2011.4 Europe hosted an estimated 1.9–3.8 million of such migrants in 2008, and the most recent estimates point to 180 000–520 000 and 58 000–105 000 of them in Germany and Switzerland, respectively.5–7

A vulnerable population

The lack of legal residency permit interacts with social, political and economic factors to create multidimensional vulnerability among undocumented migrants.8 9 In most European countries, they face significant postmigration difficulties in the context of restrictive immigration policies and lack of labour protection.2 10 Many are employed in low-skills and precarious 3D (dangerous, dirty and degrading) jobs and are exposed to abuse, exploitation and occupational hazards.11–14 Access to other basic commodities and services such as housing, education and training, food, and legal protection in case of harm or abuse is usually arduous and precarious.10 15

When compared with the resident and regular migrant populations, self-rated physical and mental health is consistently and significantly poorer among undocumented migrants in Europe.16 17 In a study conducted in 11 countries, 23% of women and 34% of men, including those in the youngest age groups, rated their health as poor or very poor.12 Undocumented migrants present high prevalence of chronic conditions in primary care settings, notably of metabolic, cardiovascular and psychiatric origins.16 18–22 Several infectious diseases are more prevalent than in the resident population, which relates more to geographical origins than to the legal status.23 24 No comparative data exist on the mortality rate ratio of undocumented migrants compared with the general population, but external (including accidents and suicides) and circulatory causes of death were 3.6 and 2.2 times more prevalent in a sample of such migrants than in the general Swedish population, respectively.25

Undocumented migrants in Europe face limited opportunities to respond to their healthcare needs with barriers to healthcare operating at different levels.12 26–28 Legal entitlement to receive medical care within the public healthcare system varies considerably between countries. A majority of countries restrict access to emergency situations exclusively.29 30 Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) play a subsidiary role, but services provided are generally of limited extent and do not cover the full range of health needs.12 Access to costly treatments in the absence of formal entitlement to healthcare is frequently restricted, which entails significant health consequences, notably in the context of severe chronic diseases such as HIV/AIDS infection.31 32 At the health service level, communication barriers, the perceived lack of specific skills and practical difficulties encountered by healthcare workers contribute to restricting the extent and quality of care.33 34 At the migrants’ level, fear of denunciation, direct costs at charge and lack of knowledge on how to navigate the health system impede adequate use of health services.12 16 35 36 These factors negatively impact the provision of health-promoting and preventive interventions such as immunisation, birth control counselling, prenatal care and screening procedures.37–39 Undocumented migrants have a higher rate of preventable hospitalisations compared with populations with full access to care and are less likely to receive preventive care.39 40

In Switzerland, the 26 cantons have a large autonomy and have the responsibility to supervise and manage their public healthcare system.41 Undocumented migrants are legally entitled to purchase the mandatory basic health insurance (which grants access to standard healthcare), but lack of awareness, financial and administrative barriers, as well as fear of denunciation contribute to the estimated 10%–20% insurance coverage.42 43 Swiss cantons have implemented different policies to bridge this access gap. Geneva and Vaud provide health services within the public healthcare system which are complemented by other services (food, shelter) provided by NGOs.42 Yet previous studies showed that undocumented migrants in Geneva tend to delay seeking care, notably for preventive interventions.38

Regularisation policies

Several regularisation programmes have been implemented in Europe, and an estimated 1.8 million undocumented migrants were granted a residency permit between 2002 and 2008.2 Switzerland has never implemented large-scale programmes, but a handful of individual applications (mainly through NGOs or lawyers’ services) have been successful to varying degrees depending on the canton. Residency permits have been granted mainly for humanitarian motives, in case of severe medical needs, long stay and satisfactory integration, absence of criminal record, and financial autonomy.5 In 2017, the Geneva Canton implemented a 2-year pilot regularisation programme (Operation Papyrus) aiming at granting 1-year residency permits to undocumented migrants meeting the following criteria: (1) stay of 10 years for individuals or 5 years for families with school-aged children; (2) basic French proficiency; (3) sufficient financial resources; and (4) lack of criminal record other than related to the residency permit.44 The programme integrates civil society actors (workers’ unions, NGOs) that act as gatekeepers between undocumented migrants and the canton authorities, and support them with the administrative process leading to regularisation.

The impact of regularisation policy on undocumented migrants’ health, well-being, living conditions and economic situation has rarely been studied in Europe. Scarce evidence shows improved access to legal employment, social welfare and insurances, with better housing and educational opportunities.45 Negative effects included enhanced professional competition associated with the lack of recognition of premigration professional qualifications. In Italy, the 2007 amnesty policy was associated with a 1.2%–2.7% point decline in low birthweight prevalence within the migrant population eligible for regularisation.46 In the USA, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals act, implemented in 2012, allowed around 800 000 undocumented young people to be temporarily regularised. Studies found a decline in psychological distress, and improvements in self-esteem, well-being and social support, and pointed to beneficial transgenerational effects on children’s mental health.47–49 No study has prospectively explored the impact of legal status change on health and well-being while taking into account undocumented migrants’ living and working conditions.

Gaps in the existing literature

While the development of knowledge about asylum seekers’ and refugees’ health is accelerating, research on undocumented migrants’ health lags behind.28 50 The number and quality of studies being limited, there are some major gaps in the current knowledge about their health and well-being and their relationship to living and economic conditions.

Most studies have been conducted in healthcare settings, thus entailing a systematic selection bias restricting their generalisability, and are cross-sectional or retrospective, which hampers the ability to measure changes over time and to identify causal relationships.12 16 17 26 35 38 51–55 Most studies are monodisciplinary, rely on a single methodology, typically measure a limited range of health indicators and usually overlook the well-being dimension. These limitations restrict the ability to foster a comprehensive understanding of the complexity and the dynamics of health and well-being evolution after regularisation in a longitudinal perspective taking into account the interactions between medical, social, legal and economic factors.

A second gap pertains to the lack of indepth understanding of the impact of legal status change (regularisation) on the health and living conditions of individual migrants but also of the rest of their family.13 16 26 35 36 38 43 In particular, there is a lack of evidence on how undocumented migrants interpret the transformation of their living conditions during and after regularisation, and the ambivalent individual and family consequences of migration and regularisation clearly need to be better understood.56 This again calls for a collection of longitudinal data.56 57 The underdevelopment of research on transnational undocumented migrant families mirrors the limited interest from policymakers.56

Theoretical perspectives

To address the limitations of the available research, our research design is supported by two main theoretical perspectives that allow assessment of the role of regularisation.

The perspective of well-being and quality of life (QoL) is typically articulated with the social determinants of health framework promoted among others by the WHO. Indeed the model developed by the WHO maps the multiple factors that affect equity in both health and well-being.58 Growing interest for well-being is evidenced by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) framework that associates objective indicators of material conditions with QoL indicators in different domains (including housing, education, income and so on).54 59 60 This framework is particularly relevant to assess the situation of newly regularised migrants, along the idea that QoL reflects the gap between individuals’ actual situation and that to which they aspire.61 We can hypothesise that undocumented migrants’ well-being might be higher than that of Swiss residents with similar levels of resources.

The dynamic approach of the life course will allow examination of undocumented migrants’ trajectories both retrospectively and prospectively. Considering how much stress and uncertainty the absence of legal documents generates, regularisation represents a major transition. At the same time, the acquisition of a legal status can bring mixed consequences, including both positive (elimination of the deportation risk, better housing) and negative (new financial constraints like taxes, competition on the labour market) influences. The life course perspective will be used to assess how regularisation modifies the balance between vulnerability, resources and reserves.62 63

Objectives of the study and research questions

This study aims to measure how regularisation impacts the health and well-being of undocumented migrants in Geneva Canton. To reach this goal, five research questions have been formulated:

What are the living conditions of undocumented migrants living in Geneva?

What are the health status, including the mental and somatic dimensions, and well-being of undocumented migrants living in Geneva?

What are the health-seeking behaviours, healthcare utilisation, including emergency services, and renouncement to medical care among undocumented migrants living in Geneva?

What is the impact of regularisation on their health and well-being and its relationship with changes in living conditions?

How do contextual factors shape the experience of transitioning towards legality for undocumented individuals and families?

Methods and data analysis

Design

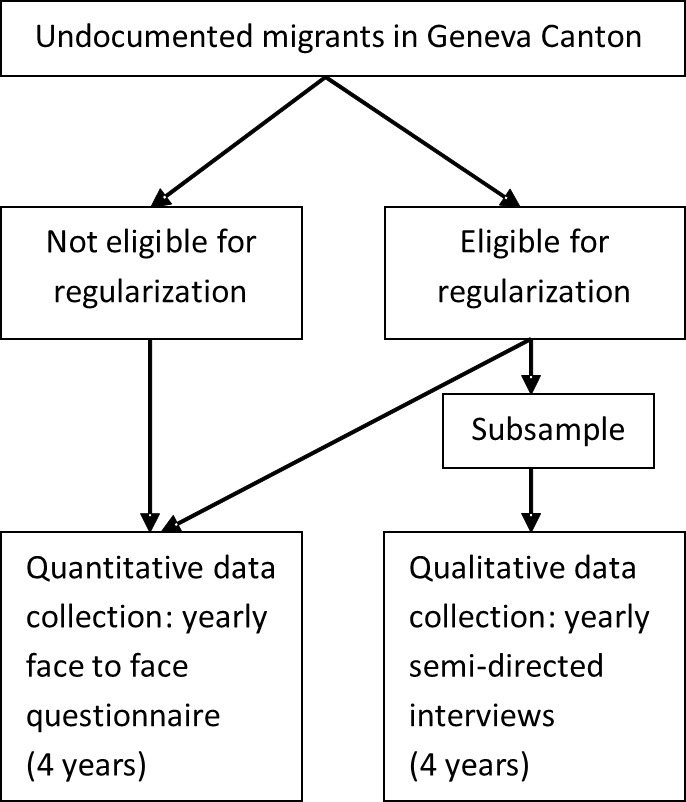

This prospective, mixed-methods observational study compares a group of undocumented migrants undergoing regularisation with a group of migrants not eligible for regularisation. A nested qualitative longitudinal study focuses on a subsample of individuals undergoing regularisation. The data collection started in 2017 and will end in 2021.

The research plan is organised to respond to the set of research questions developed on the following hypotheses: (1) undocumented migrants endure deleterious living and economic conditions compared with the general population, which has an impact on their health and well-being; (2) regularisation of the legal status impacts on health and well-being; (3) differences in health and well-being after regularisation are mediated by changes in living and economic conditions; and (4) regularisation may cause vulnerability in health and living conditions.

Setting

This study takes place in Geneva Canton, located in French-speaking Western Switzerland. The resident population is 500 000, including 10 000–15 000 undocumented migrants.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Migrants aged ≥18 years, originating from countries outside the European Union or the European Free Trade Association, living in Geneva without a valid residency permit (undocumented) for at least 3 years, who plan to stay in Geneva at least 3 more years and who have not registered as asylum seekers are eligible to participate. They are categorised into two groups: (1) those undergoing the regularisation process or who have been regularised for less than 3 months (intervention group) and (2) those who do not meet the regularisation eligibility criteria or are unwilling to apply for regularisation (control group).

Exclusion criteria

The inability to hold a basic conversation in one of the languages spoken by the investigators (French, Spanish, Portuguese, English, Albanian and Italian) is the only exclusion criterion.

Intervention

Participants eligible for legal status regularisation (intervention group) will receive a residency permit within 3–6 months after submission of their application to the canton authorities. This process will take place during the first year of data collection. The information about permit acceptance will be collected through participants and the NGOs. This permit is renewable annually.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome is self-rated health. It will be measured by comparing intragroup differences at baseline and after 3 years. Yearly measurements will allow for observations of fluctuations in such differences. This item will be measured using the 12-Item Short-Form Survey question 1, a 5-point Likert scale,64 whose large-scale use also allows for comparing the results with other groups of population. We selected the main outcome for its prognostic value in terms of morbidity and mortality.65 66

Secondary outcome measure

The secondary outcome consists of self-reported satisfaction with current life as measured through the dimensions of living condition and economic situation at baseline and after 3 years. Each domain will be measured every year with a single question using a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (absolutely not satisfied) to 10 (absolutely satisfied). This will allow to measure key dimensions of the OECD well-being framework and provide comparison with the resident population.60

Additional variables under investigations

The quantitative part explores four domains: (1) personal and family characteristics, (2) health, (3) living conditions, and (4) employment and economic situation. Table 1 presents the variables under study, to the exception of the main outcomes. These variables will be used as predictors for the main outcomes. The questionnaire was designed to provide data that allow for comparisons with the general population living in Switzerland, by using questions from population surveys such as the Household Panel Study or the Swiss Health Survey.67 68 For specific domains, we use validated measurement tools selected for their validity and reliability in non-clinical settings. We apply the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scales to screen depression and anxiety, respectively.69 70 Occupational mental health is assessed with the Maslach Burnout Inventory Test, specifically the emotional exhaustion dimension.71 We use the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index to evaluate sleep.72 We used validated translations of these scales when available, but not all questionnaires were validated in all the languages used in this study. The questionnaire was pretested with a sample of participants (n=5), allowing for iterative modifications.

Table 1.

Variables by domain

| Personal and family characteristics | Health | Living conditions | Employment and economic situation |

| Sociodemographic characteristics*†: sex; age; country of birth; nationality. | Anthropomorphic measures: weight (kg) *†; height (cm)*†. | Housing: number of rooms*; number of people sharing accommodation*†; quality of environment*; type of lease contract*†; rent price*. | Professional activity: number of employers*; sector of employment*†; number of working hours*†; working permit*. |

| Family composition*†: marital status; number of children. | Somatic health: chronic diseases*†; accidents*†; injuries; current treatment†. | Household composition: relation with household members*†. | Working conditions: hardship †; exposure to hazards†. |

| Children’s characteristics: gender; age; country of birth; country of residence; current education. | Mental health: anxiety; depression†69 70; current treatment. | Discrimination†: at the workplace; in public spaces; in healthcare settings. | Income: individual level*†; household level*†; state subsidies*. |

| Migration history: reason for leaving country of origin; date of departure from country of origin; date of arrival in Switzerland; previous and current residency status in Switzerland; visit to country of origin; regularisation procedure. | Health behaviours: sleep72; physical activity*†. | Social support: satisfaction with social relationships†. | Financial situation: ability to cover unexpected expense; remittance to country of origin. |

| Education: number of years at school; highest degree attained*†; place of education. | Access to care: health insurance; deductibles†; cost of premium; state-funded deductions*†. | Integration into local life: participation to activities†; French fluency. | |

| Professional qualification: professional training; employment record before migration. | Utilisation of the healthcare system: number of ambulatory and emergency room visits†; hospitalisation*†; affiliation with a family physician†. | ||

| Renunciation to healthcare utilisation: reasons; type of care. | |||

| Occupational health†; emotional exhaustion71; professional injuries†. |

*Variables of the Swiss Household Panel.

†Variables of the Swiss Health Survey.

Qualitative part

The following themes will be covered during the semidirected interviews: marital and family dynamics, including relationships with family members not living in Switzerland; experience of the regularisation process and its positive and negative implications; perspectives and aspirations for the future; and for parents, educational issues and aspirations for their children’s future. The interview guide has been pretested with five persons.

Participant timeline

Quantitative data will be collected by questionnaire at baseline and repeated annually during the following 3 years (four waves in total) (figure 1). Questionnaires will be filled face to face with participants in the intervention and the control groups. We restricted the follow-up to 3 years assuming that most changes in the domains under study will occur during the first 2 years, followed by a more stable situation. This restriction also aims to reduce the attrition rate. Qualitative interviews are conducted at baseline (year 1) and then every year for 3 years. They are conducted at a different time from the quantitative data collection to avoid participant fatigue.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Sample size

Considering an effect size of 0.3 for the main health outcome (self-rated health), a type 1 error of 0.05 and a power of 0.8, the total sample size is 352, rounded up to 400 to account for the possible dropout of participants over the follow-up.

The purposive, qualitative, nested study sampling includes 38 participants selected from the intervention group of undocumented migrants eligible for regularisation. The sample size is estimated to be sufficient to reach data saturation. To ensure the diversity of the sample, participants are recruited taking into account their family characteristics, notably the presence or absence of children, while ensuring the diversity of the sample regarding origin, age and gender.

Recruitment

According to the Geneva authorities, 1000–2000 undocumented migrants could be eligible for the regularisation policy. Recruitment is based on two strategies. First, undocumented migrants are informed about the study by personal contacts at NGOs acting as gatekeepers for ‘Operation Papyrus’, during public meetings held in the community, at dedicated health centres attending for undocumented migrants, through leaflets and a Facebook page. A direct phone line is accessible during office hours to respond to all enquiries. People interested in participating contact the investigators who present the study information and consent forms and engage in the first questionnaire passing if agreement is provided.

The second strategy is based on phone contacts with potential participants identified in partner NGOs’ registries of undocumented migrants. During the initial call, the investigators present the study and offer to organise a first meeting to provide more indepth information. In the absence of response, potential participants are recalled up to five times.

Retention

Undocumented migrants are highly mobile and can be lost during the follow-up. In order to account for this risk, the sample size has been increased by 12.5%. All participants undergoing the first round of data collection will be contacted yearly for the subsequent waves. In order to enhance retention into the study, the following strategies are implemented: (1) providing a material compensation (worth €10–€15) and information about available health and administrative services after each questionnaire administration; (2) discussing the need for and gaining acceptance for the next contact after 1 year on each encounter; and (3) recording a secondary phone number or email address to ensure participants are reachable. Moreover, partner NGOs inform the communities of the importance of follow-up. Contact for the following data collection will be made by phone with up to five recalls and use of email messaging in case of non-response. In order to facilitate participation and retention into the study, the field investigators can move to the preferred participant’s location to pass the questionnaire.

Participants may withdraw from the study for any reason at any time. In case of withdrawal or loss to follow-up, all data will be included for analysis until the last participant’s questionnaire.

Quantitative data collection

The questionnaire is administered face to face with participants of both groups at their preferred location in the community. It is available in the four most frequent languages (Spanish, Portuguese, French and English) spoken by undocumented migrants in Geneva. We acknowledge there may be a potential limitation related to the limited language skills of the subsample of participants not completely fluent in one of these four languages. Data are recorded on a mobile tablet using Sphinx mobile software (Le Sphinx, France) and are immediately transferred on a secure server. Interviewers are trained and supervised by a senior staff during their first interviews.

Qualitative data collection

In the qualitative section, data are collected in semidirected interviews with undocumented migrants in the process of regularisation. They are conducted in French, Spanish and English. Interviews are tape-recorded and fully transcribed.

Statistical analysis

In a first step, the two groups (intervention vs control) will be compared on all characteristics, using univariate analysis such as Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. This will allow determination of the quality of the control group selection.

To assess the evolution of health outcomes and living conditions over time, we will use multilevel linear models (logistic, Poisson or Gaussian as appropriate depending on the specific outcome) including legal status (regularised vs control) and adjusting for baseline characteristics to further account for group differences. Multilevel models account for the repeated nature of the data. To specifically focus on the different trajectories, these models will include both a random intercept and a random slope over time. Note that for rare dichotomous outcomes, we will probably need to restrict the number of covariates due to a number of events below five per predictor. In that case, we will use two strategies. First, we will apply propensity score adjustment, using all previously described covariates to compute the propensity score. Second, because the propensity score may not capture the importance of some confounders and lead to residual confounding, we will use a least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression to determine which covariates are the most useful, before using only those covariates for adjustment.

Qualitative data analysis

Thematic analyses of the transcriptions will be conducted with Atlas.ti (www.atlasti.com), combining a set of codes defined along the interview guide and new codes inductively generated over the course of the analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

All participants will provide informed consent. Results will be shared with migrant communities and NGOs supporting undocumented migrants and disseminated in scientific journals and in conferences. Fully anonymised data will be made available to researchers.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research questions, outcome measures and investigation strategies was informed by discussions conducted with community organisations active with undocumented migrants and with undocumented migrant patients seen by the main investigator (YJ). Patients were not directly involved in the design of the study, but feedback from participants after the questionnaire pretesting was used to adapt its content. One of the field investigators is a former undocumented migrant. The results will be disseminated to study participants by two channels: regular public meetings, the first of which took place on 6 November 2018, and through partner community organisations.

Discussion

This mixed-methods study aims to measure the impact of legal status change on health and well-being of undocumented migrants, taking into account living, employment and economic conditions. It will produce the first comprehensive and longitudinal evaluation of a policy response to irregular migration in Europe. The interdisciplinary approach warrants the generation of rich data about a complex phenomenon. Considering the contemporary political and scientific interest in issues pertaining to migration worldwide, this study is at the forefront to provide original, interdisciplinary and comprehensive evidence about an ill-researched population. The results will influence how such issues are framed and discussed at local, national and international levels. Data will specifically inform about unmet health needs, expectations and resources of undocumented migrants, therefore allowing for guiding clinical and public health strategies in Switzerland and similar countries. This may allow for an opportunity to mitigate inequalities in health outcomes and in access to health services. Most importantly, this study will provide a safe environment to give a voice to a silent and underserved population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the NGOs involved with the regularisation policy which helped in developing and implementing this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: YJ conceived the study, is the coprincipal investigator, drafted the protocol and wrote the manuscript. CB-J conceived the study, is the coprincipal investigator, drafted the protocol and proof-read the manuscript. GF-L, AD, SC and DSC contributed to the study conception and protocol and proof-read the manuscript. PB, PC, IG and HW reviewed the protocol and proof-read the manuscript. All authors approved the version to be published and are responsible for its accuracy.

Funding: The Parchemins study is supported by the Geneva University School of Medicine, Fondation Safra, Geneva Directorate of Health, Geneva Directorate of Social Affairs, Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, the NCCR LIVES Project and the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research (grant 100017_182208).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Geneva Canton, Switzerland (CCER 2017–00897).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. International Organization for Migration. World migration report 2018. Geneva: IOM, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kraler A, Rogoz M. Irregular migration in the European Union since the turn of the millennium –development, economic background and discussion. Database on Irregular Migration, Working paper 11/2011. Vienna: International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. International Organization for Migration. World Migration Report 2010. Geneva: IOM, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pew Hispanic Centre. A Nation of Immigrants. A Portrait of the 40 Million, Including 11 Million Unauthorized. Washington: Pew Research Centre, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morlok M, Oswald A, Meier H, et al. Les sans-papiers en Suisse en 2015. Bâle: BSS, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vogel D, Kovacheva V, Prescott H. The size of the irregular migrant population in the European Union – counting the uncountable? Int Migr 2011;49:78–96. 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2011.00700.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vogel D. Update report Germany: Estimated number of irregular foreign residents in Germany (2014). Database on Irregular Migration. Bremen: University of Bremen, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Willen SS. Migration, "illegality," and health: mapping embodied vulnerability and debating health-related deservingness. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:805–11. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fleischman Y, Willen SS, Davidovitch N, et al. Migration as a social determinant of health for irregular migrants: Israel as case study. Soc Sci Med 2015;147:89–97. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chauvin P, Simonnot N, Douay C, et al. Access to healthcare for people facing multiple vulnerability factors in 27 cities across 10 countries. Report on the social and medical data gathered in 2013 in eight European countries, Turkey and Canada. Paris: International network of Médecins du monde, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benach J, Muntaner C, Delclos C, et al. Migration and "low-skilled" workers in destination countries. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001043 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chauvin P, Parizot I, Simonnot N. Access to healthcare for undocumented migrants in 11 European countries. Paris: Médecins du Monde, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sousa E, Agudelo-Suárez A, Benavides FG, et al. Immigration, work and health in Spain: the influence of legal status and employment contract on reported health indicators. Int J Public Health 2010;55:443–51. 10.1007/s00038-010-0141-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ahonen EQ, Porthé V, Vázquez ML, et al. A qualitative study about immigrant workers' perceptions of their working conditions in Spain. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:936–42. 10.1136/jech.2008.077016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aragona M, Pucci D, Mazzeti M, et al. Post-migration living difficulties as a significant risk factor for PTSD in immigrants: a primary care study. Italian J Public Health 2012;9:e7525–1. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuehne A, Huschke S, Bullinger M. Subjective health of undocumented migrants in Germany - a mixed methods approach. BMC Public Health 2015;15:926 10.1186/s12889-015-2268-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. D’Egidio V, Mipatrini D, Massetti AP, et al. How are the undocumented migrants in Rome? Assessment of quality of life and its determinants among migrant population. J Public Health 2017;39:440–6. 10.1093/pubmed/fdw056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jackson Y, Paignon A, Wolff H, et al. Health of undocumented migrants in primary care in Switzerland. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201313 10.1371/journal.pone.0201313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson Y, Castillo S, Hammond P, et al. Metabolic, mental health, behavioural and socioeconomic characteristics of migrants with Chagas disease in a non-endemic country. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:595–603. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02965.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindert J, Ehrenstein OS, Priebe S, et al. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:246–57. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Myhrvold T, Småstuen MC. The mental healthcare needs of undocumented migrants: an exploratory analysis of psychological distress and living conditions among undocumented migrants in Norway. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:825–39. 10.1111/jocn.13670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van de Sande JSO, van den Muijsenbergh M. Undocumented and documented migrants with chronic diseases in Family Practice in the Netherlands. Fam Pract 2017;34:649–55. 10.1093/fampra/cmx032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wolff H, Janssens JP, Bodenmann P, et al. Undocumented migrants in Switzerland: geographical origin versus legal status as risk factor for tuberculosis. J Immigr Minor Health 2010;12:18–23. 10.1007/s10903-009-9271-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jackson Y, Gétaz L, Wolff H, et al. Prevalence, clinical staging and risk for blood-borne transmission of Chagas disease among Latin American migrants in Geneva, Switzerland. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010;4:e592 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wahlberg A, Källestål C, Lundgren A, et al. Causes of death among undocumented migrants in Sweden, 1997-2010. Glob Health Action 2014;7:24464 10.3402/gha.v7.24464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woodward A, Howard N, Wolffers I. Health and access to care for undocumented migrants living in the European Union: a scoping review. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:818–30. 10.1093/heapol/czt061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suess A, Ruiz Pérez I, Ruiz Azarola A, et al. The right of access to health care for undocumented migrants: a revision of comparative analysis in the European context. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:712–20. 10.1093/eurpub/cku036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Vito E, De Waure C, Specchia M, et al. Public health aspects of migrant health: a review of the evidence on health status for undocumented migrants in the European Region. Copenhagen: World Health Organisaztion (WHO) Regional Office for Europe, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cuadra CB. Right of access to health care for undocumented migrants in EU: a comparative study of national policies. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:267–71. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Karl-Trummer U, Novak-Zezula S, Metzler B. Access to health care for undocumented migrants in the EU: A first landscape of NowHereland. EuroHealth 2010;16:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pérez-Molina JA, Pulido Ortega F. Comité de expertos del Grupo para el Estudio del Sida (GESIDA) de la Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC). [Assessment of the impact of the new health legislation on illegal immigrants in Spain: the case of human immunodeficiency virus infection]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2012;30:472–8. 10.1016/j.eimc.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deblonde J, Sasse A, Del Amo J, et al. Restricted access to antiretroviral treatment for undocumented migrants: a bottle neck to control the HIV epidemic in the EU/EEA. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1228 10.1186/s12889-015-2571-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dauvrin M, Lorant V, Sandhu S, et al. Health care for irregular migrants: pragmatism across Europe: a qualitative study. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:99 10.1186/1756-0500-5-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hudelson P, Perron NJ, Perneger TV. Measuring physicians' and medical students' attitudes toward caring for immigrant patients. Eval Health Prof 2010;33:452–72. 10.1177/0163278710370157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schoevers MA, Loeffen MJ, van den Muijsenbergh ME, et al. Health care utilisation and problems in accessing health care of female undocumented immigrants in the Netherlands. Int J Public Health 2010;55:421–8. 10.1007/s00038-010-0151-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Poduval S, Howard N, Jones L, et al. Experiences among undocumented migrants accessing primary care in the United Kingdom: a qualitative study. Int J Health Serv 2015;45:320–33. 10.1177/0020731414568511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Casillas A, Bodenmann P, Epiney M, et al. The border of reproductive control: undocumented immigration as a risk factor for unintended pregnancy in Switzerland. J Immigr Minor Health 2015;17:527–34. 10.1007/s10903-013-9939-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wolff H, Epiney M, Lourenco AP, et al. Undocumented migrants lack access to pregnancy care and prevention. BMC Public Health 2008;8:93 10.1186/1471-2458-8-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martin Y, Collet TH, Bodenmann P, et al. The lower quality of preventive care among forced migrants in a country with universal healthcare coverage. Prev Med 2014;59:19–24. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mipatrini D, Addario SP, Bertollini R, et al. Access to healthcare for undocumented migrants: analysis of avoidable hospital admissions in Sicily from 2003 to 2013. Eur J Public Health 2017;27:459–64. 10.1093/eurpub/ckx039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. De Pietro C, Camenzind P, Sturny I, et al. Switzerland: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit 2015;17:1-288, xix. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. National platform for undocumented migrants access to care. Access to care for vulnerable populations in Switzerland. 2017. https://www.sante-sans-papiers.ch/FR/files/acces_aux_soins_des_vulnerables_web-4-.pdf (accessed 30 Dec 2014).

- 43. Wyssmüller C, Efionayi-Mäder D. Undocumented Migrants: their needs and strategies for accessing health care in Switzerland: Country Report on People & Practices Bern: Swiss Forum for Population and Migration Studies, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Geneva Canton Council. Opération Papyrus 2017. https://www.ge.ch/dossier/operation-papyrus (accessed 10 Jan 2017).

- 45. Kraler A, Reichel D, König A, et al. Feasibility Study on the Labour Market Trajectories of Regularised Immigrants within the European Union (REGANE I). Vienna: International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Salmasi L, Pieroni L. Immigration policy and birth weight: Positive externalities in Italian law. J Health Econ 2015;43:128–39. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Venkataramani AS, Shah SJ, O’Brien R, et al. Health consequences of the US Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) immigration programme: a quasi-experimental study. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e175–e181. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30047-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Siemons R, Raymond-Flesch M, Auerswald CL, et al. Coming of Age on the Margins: Mental Health and Wellbeing Among Latino Immigrant Young Adults Eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). J Immigr Minor Health 2017;19:543–51. 10.1007/s10903-016-0354-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hainmueller J, Lawrence D, Martén L, et al. Protecting unauthorized immigrant mothers improves their children’s mental health. Science 2017;357:1041–4. 10.1126/science.aan5893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Ingleby D, et al. Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet 2013;381:1235–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62086-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Teunissen E, Van Bavel E, Van Den Driessen Mareeuw F, et al. Mental health problems of undocumented migrants in the Netherlands: A qualitative exploration of recognition, recording, and treatment by general practitioners. Scand J Prim Health Care 2015;33:82–90. 10.3109/02813432.2015.1041830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sebo P, Jackson Y, Haller DM, et al. Sexual and reproductive health behaviors of undocumented migrants in Geneva: a cross sectional study. J Immigr Minor Health 2011;13:510–7. 10.1007/s10903-010-9367-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schoevers MA, van den Muijsenbergh ME, Lagro-Janssen AL. Self-rated health and health problems of undocumented immigrant women in the Netherlands: a descriptive study. J Public Health Policy 2009;30:409–22. 10.1057/jphp.2009.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rondet C, Cornet P, Kaoutar B, et al. Depression prevalence and primary care among vulnerable patients at a free outpatient clinic in Paris, France, in 2010: results of a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:151 10.1186/1471-2296-14-151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Castañeda H. Illegality as risk factor: a survey of unauthorized migrant patients in a Berlin clinic. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1552–60. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Glick JE. Connecting Complex Processes: A Decade of Research on Immigrant Families. J Marriage Fam 2010;72:498–515. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00715.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Clark R, Glick J, Bures R. Immigrant Families Over the Life Course:Research Directions and Needs. Journal Fam Issue 2009;30:852–72. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Commission on the social determinants of health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. World Health Organization: Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Swiss Federal Bureau of Statistics. Measuring well-being 2018. 2018. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/themes-transversaux/mesure-bien-etre.html.

- 60. OECD. Measuring Well-being and Progress: Well-being Research. 2018. http://www.oecd.org/statistics/measuring-well-being-and-progress.htm.

- 61. Fry PS. Guest editorial: aging and quality of life (QOL)--the continuing search for quality of life indicators. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2000;50:245–61. 10.2190/44NJ-K9YQ-H44X-H3HV [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Spini D, Bernardi L, Oris M. Vulnerability Across the Life Course. Res Hum Dev 2017;14:1–4. 10.1080/15427609.2016.1268891 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cullati S, Kliegel M, Widmer E. Development of reserves over the life course and onset of vulnerability in later life. Nat Hum Behav 2018;2:551–8. 10.1038/s41562-018-0395-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Benyamini Y, Idler Y. Community Studies Reporting Association between Self-Rated Health and Mortality:Additional Studies, 1995 to 1998. Res Aging 1999;21:392–401. [Google Scholar]

- 66. DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, et al. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:267–75. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tillmann R, Voorpostel M, Antal E, Kuhn U, et al. The Swiss Household Panel Study: Observing social change since 1999. Longit Life Course Stud 2016;7:15 10.14301/llcs.v7i1.360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. Swiss Health Study 2017. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/sante/enquetes/sgb.html#1002476496 (accessed 03 Aug 2018).

- 69. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:345–59. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav 1981;2:99–113. 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mollayeva T, Thurairajah P, Burton K, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2016;25:52–73. 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.