Abstract

Objectives

In cancer studies, the target received dose intensity (tRDI) for any regimen, the intended dose and time for the regimen, is commonly taken as a proxy for achieved RDI (aRDI), the actual individual dose and time for the regimen. Evaluating tRDI/aRDI mismatches is crucial to assess study results whenever patients are stratified on allocated regimen. The manuscript develops a novel methodology to highlight and evaluate tRDI/aRDI mismatches.

Design

Retrospective analysis of a randomised controlled trial, MRC BO06 (EORTC 80931).

Setting

Population-based study but proposed methodology can be applied to other trial designs.

Participants

A total of 497 patients with resectable high-grade osteosarcoma, of which 19 were excluded because chemotherapy was not started or the estimated dose was abnormally high (>1.25 × prescribed dose).

Intervention(s)

Two regimens with the same anticipated cumulative dose (doxorubicin 6×75 mg/m2/week; cisplatin 6×100 mg/m2/week) over different time schedules: every 3 weeks in regimen-C and every 2 weeks in regimen-DI.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

tRDI distribution was measured across groups of patients derived from k-means clustering of treatment data. K-means creates groups of patients who are aRDI-homogeneous. The main outcome is the proportion of tRDI values in groups of homogeneous aRDI.

Results

For nearly half of the patients, there is a mismatch between tRDI and aRDI; for 21%, aRDI was closer to the tRDI of the other regimen.

Conclusions

For MRC BO06, tRDI did not predict well aRDI. The manuscript offers an original procedure to highlight the presence of and quantify tRDI/aRDI mismatches. Caution is required to interpret the effect of chemotherapy-regimen intensification on survival outcome at an individual level where such a mismatch is present.

The study relevance lies in the use of individual realisation of the intended treatment, which depends on individual delays and/or dose reductions reported throughout the treatment.

Trial registration number

Keywords: received dose intensity, osteosarcoma, chemotherapy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study proposes an innovative method based on machine learning.

This method highlights and evaluates potential mismatches between intended and achieved treatment-intensity in cancer studies.

The method’s applicability is currently limited to retrospective analyses.

The study contributes to the development of precision medicine because the method can address the relationship between individual dose intensity and survival.

Introduction

In chemotherapy-based treatment of cancer, there is substantial interest in relating dose escalation of cytostatic-agents and treatment-time compression to the clinical outcomes of interest. Treatment intensity with respect to both dose and time is generally summarised using a single measure called ‘received dose intensity’ (RDI). RDI was first described by Hryniuk as the given dose over a given time period1; this definition can apply to both single cytostatic agents and drug combinations.2 The effect of RDI on clinical response and survival has been a central issue in chemotherapy treatment for more than 30 years. The prognostic and predictive value of high RDI in cancer survivorship has been discussed by many authors, including in breast cancer,3–5 lymphoma,4 renal cell cancer6 and pancreatic cancer.7 There might be a threshold beyond which further increasing DI provides no additional effect.4 8 9 Investigating the relationship between increased RDI and improved outcome is complicated by the effect of multiple factors.9

In randomised controlled trials (RCTs), the gold standard is to analyse patients according to the treatment regimen to which they were allocated, including in trials where the aim was to investigate whether increased RDI of chemotherapy would improve survival outcome. In dose-response trials, the intended cumulative dose and planned treatment duration together define the tRDI for each regimen. The ratio of the actual dose for any given patient and their actual treatment time, that is, the aRDI, may not be the tRDI in practice. In many situations, tRDI might not be a good predictor of aRDI. Depending on the treatment-delivery protocol, the relationship between tRDI and aRDI might vary sufficiently that many patients, if reviewed without reference to allocated treatment, look to have been treated according to the other regimen. This mismatch might be driven, for example, by adverse events and unwanted side-effects from the allocated treatment.10 11

We examined individual’s treatment data and evaluated the extent to which baseline computations of tRDI agree with the actual intensity of individual treatments observed, that is, aRDI. The aim was to present a method to address the relationship between RDI and survival at a personalised level. The motivating example was the MRC BO06 RCT for patients with osteosarcoma.12 This was a dose-escalation trial and therefore was ideal to investigate any mismatch between aRDI and tRDI. The two regimens in MRC BO06 were designed to deliver the same cumulative dosage over two-time schedules, and there was concern that clinicians would not or could not implement the protocol regimens. The efficacy of systemic treatment has been already demonstrated in osteosarcoma but, in spite of a significant association between high RDI and short-term clinical response, no long-term survival improvement had been demonstrated from treatment intensification.13 14

Patients and methods

Patients

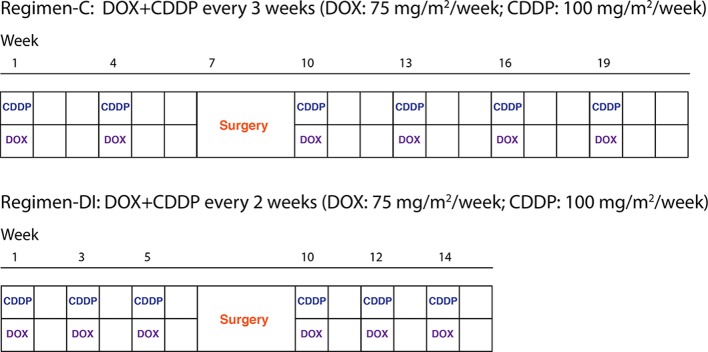

The data for our study were obtained, by formal data release request, from the MRC-BO06/EORTC-80931 RCT for patients with non-metastatic high-grade osteosarcoma which recruited between 1993 and 2002. The trial randomised patients between conventional treatment with doxorubicin (DOX) and cisplatin (CDDP) given every 3 weeks (regimen-C) versus a dose-intense regimen of the same two drugs given every 2 weeks (regimen-DI), supported by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Chemotherapy was administered for six cycles (a cycle is a period of either 2 or 3 weeks depending on the allocated regimen), before and after surgical removal of the primary osteosarcoma. In both the conventional (C) and dose-intense arms, DOX (75 mg/m2) plus CDDP (100 mg/m2) were given over six cycles. Surgery to remove the primary tumour was scheduled at week 6 after starting treatment in both arms, that is, after 2×DOX+ CDDP in regimen-C and after 3×DOX+ CDDP in regimen-DI. Postoperative chemotherapy was intended to resume 3 weeks after surgery in both arms; figure 1 shows the trial design. The trial reported on the association between levels of tumour necrosis observed at surgery—also known as histological response—and survival. Additional details can be found in the primary analysis of the trial.12

Figure 1.

Patients are randomised at baseline to one of the two regimens, with identical anticipated cumulative dose but different duration.

The received dataset included 497 eligible patients. We excluded a further 19 patients who did not start chemotherapy (13) or reported an abnormal dosage of one or both agents (six; given dose >1.25 × prescribed dose).

Patient involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the original RCT, which was run before this was recognised as good practice, nor in this study; patient and public involvement is not common in methodological studies.

Calculating target and achieved RDI

Both tRDI and aRDI are computed according to the ratio δ/τ, where δ is the standardised cumulative dose and τ is the standardised time-on-treatment15; δ and τ are computed for the allocated regimen for tRDI (ie, two pairs of values, one for each arm). For aRDI, δ and τ are computed for each specific subject by using patients’ treatment-data.

The standardised cumulative dose, δ, is computed by averaging single-agent standardised cumulative dose, that is, δ=0.5 × (δDOX + δCDDP). Single-agent cumulative doses, standardised by body surface area (BSA) which is a function of height and weight, are computed according to δAGENT = ∑CYCLE (dAGENT, CYCLE/BSACYCLE)/(6×planned dose of agent), where cycle is each cycle of two-drug chemotherapy, d is the given dose of agent in mg, BSACYCLE is the patient’s body surface area at the beginning of cycle and the sum is over the six cycles; the planned dose of agent is in mg/m2. In case agent is omitted or treatment discontinued, dAGENT, CYCLE = 0 for all omitted/discontinued cycle.

The standardised time-on-treatment, τ, is defined as the difference in days between the starting dates of the first and the last cycle reported on the case report form (including the surgery window which was taken to be 21 days), divided by the intended duration of regimen-DI. In this way, we are considering the intensity of individual treatments relative to the anticipated DI regimen.16 The intended duration of both regimens was computed as: (5×14)+21 + 1=92 days for regimen-DI, and (5×21)+21 + 1=127 days for regimen-C, which is a difference of 35 days.

In general, any two patients—even two regimen-C or two regimen-DI patients—will report different values of τ and δ depending on the individual realisation of their intended treatment, that is, depending on the delays and dose reductions required during chemotherapy due to toxicity.

According to the definitions above, we expect similar values of δ but different values of τ. As the difference in the planned duration between the regimens is 35 days, we expect a difference of about 35/92=0.38 between the τ of a regimen-C and a regimen-DI patient, that is, the tRDI for regimen-DI is 1.00 and tRDI for regimen-C is 1.00/1.38=0.72.

Displaying of treatment data: the time–dose plane

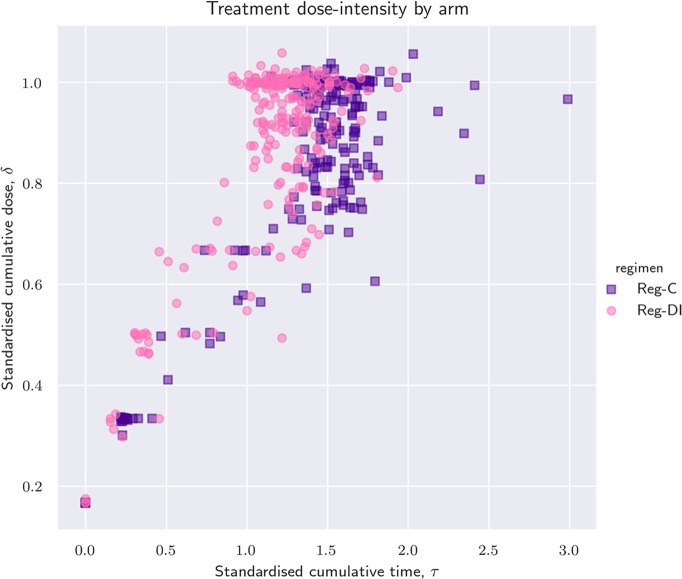

Graphical techniques are used to visualise how treatments were administered with respect to cumulative dose reductions and cumulative delays. We draw patients in the time–dose plane, also called τδ-plane, (see figure 2). In this plane, each patient is represented by a point: the x-coordinate is the standardised time-on-treatment, τ and the y-coordinate is the standardised cumulative dose received, δ. For patients who completed all six anticipated cycles, the quantity δ/τ is close to the achieved RDI as defined by Lewis.15

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of standardised dose verses standardised time coloured by intended regimen. The ratio δ/τ is the achieved received dose intensity (RDI), which graphically corresponds to the slope of a line joining the patient with the point of coordinates (0,0), that is, a fictitious patient that never initiated treatment. For patients that completed the protocol, the achieved RDI is practically equivalent to the RDI computed by Lewis et al.15

Statistical methods

Groups of patients with similar aRDI were identified by k-means clustering17 (unsupervised machine learning) and plotted on the time–dose (τδ) plane. Patients lying close to each other on the τδ-plane reported similar cumulative doses in a similar time span and therefore they have a similar aRDI.

We evaluated any mismatch between tRDI and aRDI by looking at the distribution of tRDI across the aRDI-homogeneous patient groups (the clusters); the number of groups, k, was progressively increased. The precision achieved by a specific cluster was the largest between the proportion of regimen-C and regimen-DI patients contained in that group. We evaluate the clustering result at different values of k by computing homogeneity, completeness and V-measure18 given the individual intended regimen. Homogeneity and completeness both ranged between 0 and 1. A larger value of homogeneity indicated that groups tended to be formed by patients randomised to the same regimen. In particular, high homogeneity yields high precision in all clusters. A high completeness score means that patients randomised to the same regimen belonged to the same cluster. The V-measure was the harmonic mean of homogeneity and completeness. The implementation of k-means was provided by Python V.3.6.3 library scikit-learn.19

Results

Individual treatment data and presence of t/aRDI mismatch

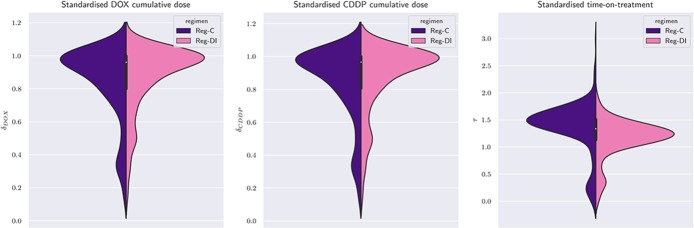

Summary measures of standardised time on treatment, τ and mean cumulative dose, δ, are illustrated in table 1. As expected, regimen-C and regimen-DI show similar distributions of the average cumulative dose, δ. The mean difference in τ between regimen-C and regimen-DI is 0.21, which corresponds to approximately 3 weeks (0.21×92 = 19 days), while the median difference is slightly larger (0.24×92 = 22 days). The primary analysis of MRC BO0612 already noted a smaller-than-anticipated difference in the median values, which was expected to be 5 weeks. The IQR of τ for regimen DI (from 1.07×92 = 98 to 1.35×92 = 124 days) has limited overlap with that of regimen-C (from 1.34×92 = 123 to 1.60×92 = 147 days). The IQR, by definition, contains the central 50% of observed times, therefore implying that 25% of regimen-DI patients completed treatment in more than 124 days, that is, in a period closer to the target median-duration of regimen-C than the target median duration of regimen-DI. On the other hand, 25% of regimen-C patients completed treatment in less than 123 days, that is, in a period that is closer to the target median duration of regimen-DI than to the target median-duration of regimen-C. Figure 3 shows the distribution of single-drug standardised cumulative doses (figure 3; left and central panels) and standardised time-on-treatment (figure 3; right panel), stratified by the intended regimen.

Table 1.

Statistical properties of standardised time-on-treatment (τ) and cumulative dose (δ)

| Mean | SD | Min | Median | IQR | Max | ||

| Regimen-C (n=235) | τ | 1.36 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.464 | (1.34, 1.60) | 2.99 |

| δ | 0.84 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.94 | (0.78, 1.00) | 1.06 | |

| Regimen-DI (n=243) | τ | 1.15 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 1.22 | (1.07, 1.35) | 1.93 |

| δ | 0.87 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.96 | (0.82, 1.00) | 1.06 |

The reference value of τ is 1, which corresponds to 84 days, that is, the planned duration of regimen-DI. The reference value of δ is 1, which corresponds to 450 mg/m2 of doxorubicin plus 600 mg/m2 of cisplatin.

Figure 3.

Violin plot of both single-agent standardised doses and standardised time. A violin plot combines features of a boxplot to features of a histogram in the same figure. The central candlestick has three components: the thick part displays the IQR, the white dot the median, and the thin vertical lines the whiskers of a boxplot. On both sides of the candlestick lies a smoothed histogram (regimen-C on the left and regimen-DI on the right). When the violin is symmetric, then the distribution of the quantity is the same in both regimens. This is true for the first two panels (δDOX and δCDDP), but not for the rightmost (τ). Yet, the two halves of the violin of τ do overlap for a substantial part, reflecting the findings of table 1. Patients who discontinued after the first cycle are present. For these patients, τ=0 and consequently, the support of the violin of τ extends to negative values.

Figure 2 shows a scatter plot of τ and δ. DI-patients are depicted as pink circles, while C-patients are represented by purple squares. Since pink and purple points are not horizontally separated, it would be difficult to distinguish many of the regimen-DI and regimen-C patients if we were to draw again figure 2 with a single colour and a single marker. This shows that there was variability in how each regiment was delivered (ie, a t/aRDI-mismatch) because the correspondence between intensity of intended and delivered treatment is commonly confused.

Analysis of clustering results and evaluation of t/aRDI mismatch

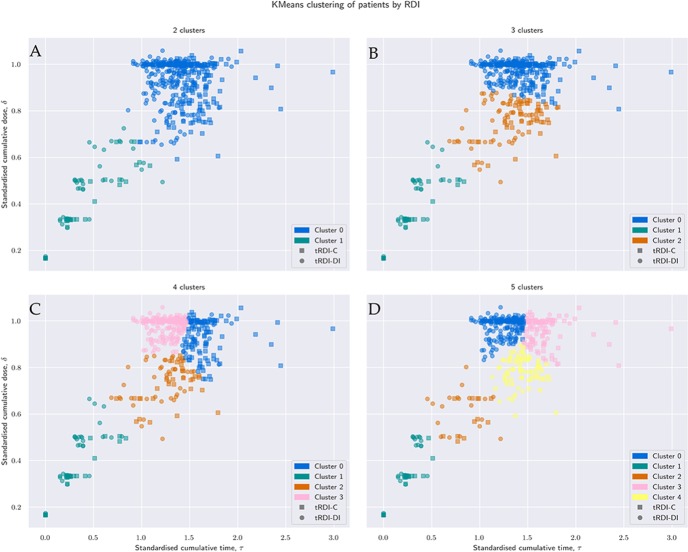

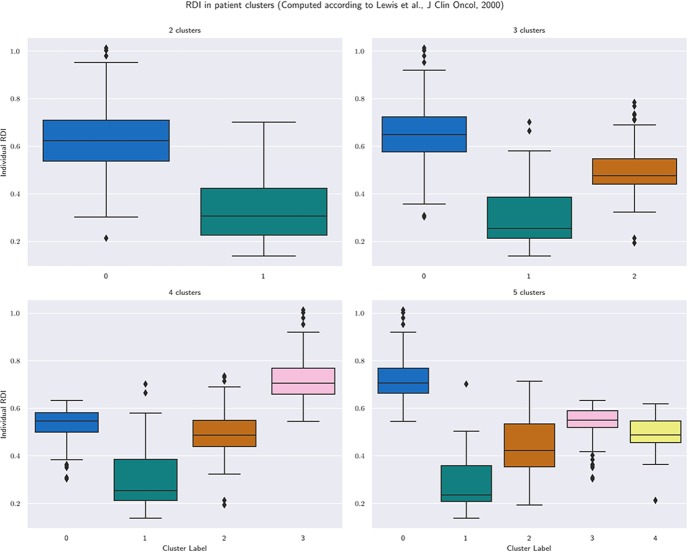

Figure 4A–D shows results with 2, 3, 4 and 5 clusters, regardless of allocated treatment, that is, four groupings of patients in the τδ-plane. Groups are labelled with a progressive index starting from 0. With more clusters, we achieve a more detailed grouping: with only 2 or 3 clusters, the clustering is based more on separation in δ, that is, based on similarity of dose-reductions only; with 4 or 5 clusters, the biggest group of patients with the highest cumulative dose (cluster 0 in figure 4A and B) is split around τ=1.5, that is, about 135 days. By increasing k, we can obtain at least one cluster where we can find a majority for regimen-C patients and one with a majority of regimen-DI patients. The precision achieved within each cluster is reported in table 2 together with the median values of standardised cumulative dose and time-on-treatment, number of cycles completed and individual aRDI computed as in Ref.15 For all values of k, figure 5 summarises individual aRDI values in each patient group; each boxplot refers to the corresponding clustering result shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Clustering result for different values of the desired number of clusters, k. Size, composition, precision and median values of quantities of interest are reported for each cluster and each value of k by table 2. For each of the four clustering results, figure 5 summarises the individual values of received dose intensity computed according to Lewis et al.15

Table 2.

Precision of the clustering results and median values of standardised cumulative dose, standardised time-on-treatment, number of cycles completed and received dose intensity (RDI) computed according to Lewis et al 15

| Cluster label | N. pts. | N. Reg-C | N. Reg-DI | Precision (%) | δ | τ | N. cycles | RDI | |

| k=2 | Cluster 0 | 407 | 201 | 206 | 51 | 0.97 | 1.38 | 6 | 0.62 |

| Cluster 1 | 71 | 34 | 37 | 52 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 3 | 0.31 | |

| k=3 | Cluster 0 | 319 | 152 | 167 | 52 | 1.00 | 1.38 | 6 | 0.65 |

| Cluster 1 | 57 | 29 | 28 | 51 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 2 | 0.25 | |

| Cluster 2 | 102 | 54 | 48 | 53 | 0.78 | 1.34 | 6 | 0.48 | |

| k=4 | Cluster 0 | 135 | 108 | 27 | 80 | 0.95 | 1.60 | 6 | 0.55 |

| Cluster 1 | 57 | 29 | 28 | 51 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 2 | 0.25 | |

| Cluster 2 | 76 | 35 | 41 | 54 | 0.75 | 1.30 | 6 | 0.49 | |

| Cluster 3 | 210 | 63 | 147 | 70 | 1.00 | 1.29 | 6 | 0.71 | |

| k=5 | Cluster 0 | 210 | 62 | 148 | 70 | 1.00 | 1.28 | 6 | 0.71 |

| Cluster 1 | 46 | 25 | 21 | 54 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 2 | 0.24 | |

| Cluster 2 | 31 | 12 | 19 | 61 | 0.64 | 0.84 | 4 | 0.42 | |

| Cluster 3 | 114 | 90 | 24 | 79 | 0.98 | 1.60 | 6 | 0.55 | |

| Cluster 4 | 77 | 46 | 31 | 60 | 0.79 | 1.42 | 6 | 0.49 | |

Figure 5.

Individual received dose intensity (computed according to Lewis et al 15) in groups obtained by clustering patients in the τδ-plane.

Table 3 shows homogeneity, completeness and V measure for each value of k. The clustering result shows the highest scores for k=4. This yields a grouping where clusters are the most homogeneous, that is, patients in the same group tend to share the same intended treatment, and the most complete, that is, patients randomised to the same regimen lie in the same cluster. We can interpret the clustering results as follows.

Table 3.

Scores of homogeneity, completeness and V-measure for the clustering result at different values of the desired number of clusters, k

| Homogeneity | Completeness | V measure | |

| k=2 | 0.00008 | 0.00014 | 0.00010 |

| k=3 | 0.00142 | 0.00116 | 0.00128 |

| k=4 | 0.13125 | 0.07194 | 0.09294 |

| k=5 | 0.12335 | 0.06106 | 0.08168 |

The value k=4, gives the highest homogeneity, meaning that patients in each group are more likely to share the regimen they were randomised to. Adding a fifth group decreases both homogeneity and completeness because now there are three groups that cannot differentiate well between regimen-C and regimen-DI. In general, additional groups might increase homogeneity but will always decrease completeness.

Using only two or three clusters, we achieve balanced groups with nearly the same proportion of regimen-C and regimen-DI patients because the stratification is based on dose reductions, and these have very similar patterns in the two regimens.

Using four clusters, we achieve a precision of 80% and 70% in the two groups with the highest cumulative dose reported, that is, cluster 0 and cluster 3. Although these ideally correspond to regimen-C (cluster 0) and regimen-DI (cluster 3), there are 27+63= 100 patients (21% of sample) who reported an aRDI closer to the tRDI of the regimen they were not randomised to. The remaining 2 groups contain 57+76 = 133 patients (28% of the sample) and achieve a precision of about 50%–55%, that is, each contains about the same amount of regimen-C and regimen-DI patients. According to table 2, cluster 1 and cluster 2 can be interpreted as early treatment-discontinuations and treatments completed with major reductions, respectively.

With five clusters (figure 4D), we achieve similar precision to four clusters in that two groups with highest cumulative dose (cluster 0 and cluster 3), while the remaining clusters again achieve a precision around 50%. However, by using five clusters, it is easier to identify groupings of patients who did not complete the allocated regimen. According to table 2, the remaining three clusters can be interpreted as follows: cluster 1: group of patients with early treatment-discontinuations, cluster 2: group of patients with late discontinuations and cluster 4: group of patients with full treatment with major reductions.

Results shown in table 2 and figure 4 suggest that four clusters (k=4) is the most appropriate choice: it has the advantage of returning higher precision than k=3 and not returning very small clusters like k=5. In conclusion, k=4 seemed to be the optimal number of groups for the MRC BO06 dataset. This method suggested that tRDI seems to have had small to no predictive ability for 28% of patients. Moreover, there was an additional 21% of patients, belonging to cluster 0 or cluster 3, that showed some evidence of an RDI mismatch because their individual aRDI is closer to the tRDI of the other regimen.

Discussion

Our principal finding is that tRDI did not seem to be a good predictor for aRDI in the MRC BO06 dataset. In order to explore this, we have proposed a machine-learning powered method for quantifying the correspondence between tRDI and aRDI. We illustrated the method within the context of osteosarcoma treatment because this is an application of great potential interest. In osteosarcoma, increased RDI is associated with higher levels of tumour necrosis—which are known to decrease the hazard of survival outcome13 14—yet increased RDI does not translate to improved survivorship.20–22 Our results indicate that distinguishing regimen C from regimen DI patients by simply looking at their cumulative dose and time on treatment is often not possible because of t/aRDI mismatch (figure 2): many patients received their allocated regimen yet lie closer to the aRDI observed for patients randomised to the other arm. From the point of view of aRDI and its effect on survival outcome, they could be thought of as treatment switches. Finally, we identified in the original cohort four groups (figure 4, bottom left panel) that capture groupings of treatment discontinuations, major reductions, treatment completions and treatment completions over a longer time. The analysis of these groups revealed that for 49% of patients, tRDI was not a good predictor of aRDI. Even considering treatment completions only, the mismatch is still very high (21%).

This study discusses the use of individual realisations of the intended treatment, which depends on delays and dose reductions reported throughout the course of treatment. A novel method to estimate the potential intended/achieved-treatment mismatch is illustrated. The method can be applied to other randomised clinical trials (see online supplementary appendix for details). The mismatch is more likely to arise when the arms of the trial have a similar design. More research is required to investigate the presence of mismatch between achieved and target RDI in a prospective way. This method would be a helpful tool at interim analyses: if treatments are looking muddled, then the trial is going to be difficult to interpret and the investigators might wish to take early action.

bmjopen-2018-022980supp001.pdf (365.6KB, pdf)

The relationship between RDI and long-term cancer survivorship is usually addressed by stratifying patients on the allocated regimen. The method proposed in this manuscript keeps dose and time apart while guaranteeing that interpretation of the results in terms of aRDI is still possible. However, compared with classical stratification at baseline, the method proposed here forms groups of similar aRDI which are no longer randomised. While this fact does not impact the capability of the method of highlighting a/tRDI mismatches, covariate rebalancing23 might be required in order to address other clinical research questions.

When investigating the association between doses and survival outcomes, it is crucial to address departure of individual, observed RDI values from those anticipated. In the particular case of MRC BO06, we have shown that a substantial proportion of regimen-C and regimen-DI patients cannot be distinguished based on the reported treatment-intensity. Since MRC-BO06 was an RCT, any difference we may find in the survival curves for regimen-DI and regimen-C must be associated with tRDI. However, had the BO06 study found that regimen-DI survive better, we might erroneously claim that higher aRDI is associated to better survival. In other words, we could think we can support individual regimen compression. However, this is not guaranteed if tRDI and aRDI are not the same.

For this reason, we recommend the use of the proposed method in exploratory analyses and we put a call on all relevant stakeholders to amend their statistical analysis plans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gordana Jovic and Medical Research Council for sharing the dataset used in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: CL, MRS and MF conceived and designed the study; MRS collected the data; CL, CS and MF performed the statistical analysis and interpreted the results. CL, MRS and MF drafted the manuscript while CS, JKA, HG, JW and PCWH revised it critically. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and have contributed to the manuscript. MF is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by the Dutch Foundation KiKa (Stichting Kinderen Kankervrij), grant 163, through the project meta-analysis of individual patient data to investigate dose-intensity relation with survival outcome for osteosarcoma patients.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Permission to recruit patients to the MRC BO06/EORTC 80931 protocol was provided by the appropriate national and local regulatory and local committees. Link-anonymised data were used for the purposes of this study, and the use of the data was consistent with the consent taken. Because it involved retrospective review, the project was exempt from Human Subjects protection requirements by the Institutional Review Board of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Access to the full dataset of MRC BO06 trial can be requested to MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL, Institute of Clinical Trials and Methodology, UCL, London.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Hryniuk WM, Goodyear M. The calculation of received dose intensity. J Clin Oncol 1990;8:1935–7. 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.12.1935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hryniuk W, Frei E, Wright FA. A single scale for comparing dose-intensity of all chemotherapy regimens in breast cancer: summation dose-intensity. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:3137–47. 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Citron ML. Dose density in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Cancer Invest 2004;22:555–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wildiers H, Reiser M. Relative dose intensity of chemotherapy and its impact on outcomes in patients with early breast cancer or aggressive lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2011;77:221–40. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yuan JQ, Wang SM, Tang LL, et al. Relative dose intensity and therapy efficacy in different breast cancer molecular subtypes: a retrospective study of early stage breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;151:405–13. 10.1007/s10549-015-3418-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shirotake S, Yasumizu Y, Ito K, et al. Impact of second-line targeted therapy dose intensity on patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2016;14:e575–e583. 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yabusaki N, Fujii T, Yamada S, et al. The significance of relative dose intensity in adjuvant chemotherapy of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma-including the analysis of clinicopathological factors influencing relative dose intensity. Medicine 2016;95:e4282 10.1097/MD.0000000000004282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ozols RF. Ovarian cancer: is dose intensity dead? J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4157–8. 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Loschi S, Dufour C, Oberlin O, et al. Tandem high-dose chemotherapy strategy as first-line treatment of primary disseminated multifocal Ewing sarcomas in children, adolescents and young adults. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015;50:1083–8. 10.1038/bmt.2015.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khan S, Dhadda A, Fyfe D, et al. Impact of neutropenia on delivering planned chemotherapy for solid tumours. Eur J Cancer Care 2008;17:19–25. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Repetto L. CIPOMO investigators. Incidence and clinical impact of chemotherapy induced myelotoxicity in cancer patients: an observational retrospective survey. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2009;72:170–9. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lewis IJ, Nooij MA, Whelan J, et al. Improvement in histologic response but not survival in osteosarcoma patients treated with intensified chemotherapy: a randomized phase III trial of the European Osteosarcoma Intergroup. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:112–28. 10.1093/jnci/djk015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luetke A, Meyers PA, Lewis I, et al. Osteosarcoma treatment - where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat Rev 2014;40:523–32. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ta HT, Dass CR, Choong PF, et al. Osteosarcoma treatment: state of the art. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2009;28:247–63. 10.1007/s10555-009-9186-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewis IJ, Weeden S, Machin D, et al. Received dose and dose-intensity of chemotherapy and outcome in nonmetastatic extremity osteosarcoma. European Osteosarcoma Intergroup. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:4028–37. 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.24.4028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hryniuk W, Bush H. The importance of dose intensity in chemotherapy of metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1984;2:1281–8. 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.11.1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. MacQueen JB. Some Methods for classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations. Proceedings of 5th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley:University of California Press, 1967:281–97. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosenberg A, Hirschberg J. V-measure: A conditional entropy-based external cluster evaluation measure. Proceedings of the 2007 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning, Prague:Omnipress, 2007:410–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res 2011;12:2825–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smeland S, Muller C, Alvegard TA, et al. SSGVIII study: prognostic factors for outcome and role of replacement salvage chemotherapy for poor histologic responders. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:488–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bacci G, Longhi A, Versari M, et al. Prognostic factors for osteosarcoma of the extremity treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: 15-year experience in 789 patients treated at a single institution. Cancer 2006;106:1154–61. 10.1002/cncr.21724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meyers PA, Gorlick R, Heller G, et al. Intensification of preoperative chemotherapy for osteogenic sarcoma: results of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering (T12) protocol. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2452–8. 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xie J, Liu C. Adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimator and log-rank test with inverse probability of treatment weighting for survival data. Stat Med 2005;24:3089–110. 10.1002/sim.2174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022980supp001.pdf (365.6KB, pdf)