To the Editor:

Between 20 and 40% of traumatically injured patients develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and/or depression within a year post-injury [1]. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Trauma strongly recommends that trauma centers routinely screen for PTSD and depression [2]. Resources that effciently enhance capacity to identify good candidates for mental health follow-up are therefore a priority. The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) [3] is a 13-item measure of acute emotional and physiological distress, a strong predictor of PTSD [4,5]. The relation between peritraumatic distress and development of depression is understudied. One prospective study with Japanese patients following a motor vehicle accident (MVA) found a relation between the PDI and depressive and anxiety symptoms one-month post-injury [6,7].

We used data from a prospective clinical sample of patients admitted to a Level I trauma center following traumatic injury to examine the predictive value of the PDI relative to depression severity and clinical status 30-days post-injury, and to establish optimal PDI cutoff scores predicting clinically elevated depression. Data were obtained from patients enrolled in the Trauma Resilience and Recovery Program (TRRP) [8] between August 2015 and July 2017. Patients were approached by TRRP staff who administered the PDI, provided psychoeducation about emotional recovery, and requested permission to contact them by telephone to conduct a 30-day mental health screen. Staff contacted patients approximately 30-days post-injury (Median days = 39) and administered a brief mental health screen, which included the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a 9-item self-report measure of depression severity [9]. Total scores ≥ 10 on the PHQ-9 indicate clinically elevated depression [10].

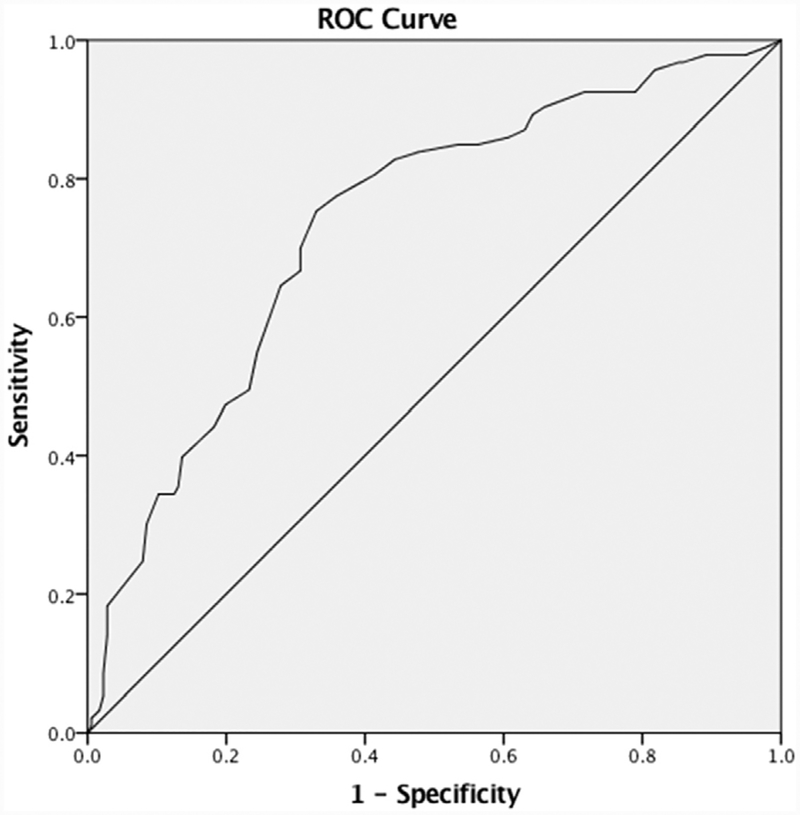

The sample included 269 patients who completed the 30-day screen. Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Results indicated that the PDI and PHQ-9 demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.83 and 0.91, respectively). The linear regression analysis predicting 30-day PHQ-9 scores from the PDI was significant (β = 0.41, F[1, 267] = 54.44, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.17). Results of the logistic regression indicated that PDI scores predicted elevated clinical status on the PHQ-9 (β = 0.08 SE = 0.01, Wald = 34.63, p < 0.001, OR = 1.08, 95% CI [1.05, 1.11],R2Nag = 0.20). Results of the ROC curve analysis predicting 30-day elevated clinical status was significant (AUC = 0.74, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.67,0.80], p < 0.001). Examination of the coordinate points of the ROC curve suggested an optimal PDI cutoff score of 21 (sensitivity = 70%; speci-ficity = 69%) predicting clinically elevated PHQ-9 scores. A score of 11 predicted elevations with 90% sensitivity (specificity = 34%), and a score of 34 predicted elevations with 90% specificity (sensitivity = 34%) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Variable | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 44.11 (18.75) |

| PDI total score | 20.52 (11.84) |

| PHQ-9 total score | 7.66 (7.45) |

| n (%) | |

| PHQ-9 elevation | |

| Clinically elevated | 93 (34.57) |

| Non-clinically elevated | 176 (65.43) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 183 (68.0) |

| Female | 86 (32.0) |

| Race | |

| Black | 104 (38.7) |

| White | 141 (52.6) |

| Asian | 1 (0.4) |

| Other/Bi-Racial | 22 (8.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 255 (94.8) |

| Hispanic | 13 (4.8) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) |

| Trauma type | |

| Motor vehicle collision | 126 (46.8) |

| Motorcycle collision | 33 (12.3) |

| Fall | 51 (19.0) |

| Gunshot wound/stabbing | 28 (10.4) |

| Pedestrian vs. auto | 20 (7.4) |

| Assault/abuse | 5 (1.9) |

| Medical injury | 1 (0.4) |

| Other | 5 (1.9) |

Note. N = 269; PDI = peritraumatic distress inventory; PHQ-9 = patient health questionnaire.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for clinically elevated PHQ-9 scores.

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective evaluation of the predictive value of the PDI relative to 30-day post-injury depression in patients admitted to a U.S. trauma center. The sample’s diversity with respect to trauma-type (Table 1) extends prior findings with Japanese MVA survivors [6,7]. A cutoff score of 21 was found to accurately identify 70% of patients with, and 69% of patients without clinically elevated depression 30-days post-injury. Some providers may prefer to use a more conservative cutoff score of 11 to identify a higher proportion of patients who might require further screening and services. Some providers also may prefer to use brief depression screens to predict emotional recovery, although such screens tend to ask about symptoms in the past two weeks or month, a symptom timeframe that predates the injury and therefore may cloud interpretation. The PDI is a low-burden instrument that assesses acute distress specific to the immediate post-injury time frame and is predictive of both PTSD and depression 30-days post-injury. Research is needed to extend these findings using diagnostic interviews and other predictive factors (e.g., prior trauma). These data suggest that the PDI may add predictive value as trauma centers seek to identify strategies to meet the mental health needs of their patients, consistent with ACS guidelines.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Center for Telehealth, the South Carolina Telehealth Alliance, the Duke Endowment (grant number 6657-SP), and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant numbers MH108250, MH107641). The authors wish to acknowledge the MUSC Department of Surgery’s support of the Trauma Resilience and Recovery Program (TRRP). The authors also wish to acknowledge TRRP staff, in particular Jennifer Winkelmann, MS and Olivia Eilers, BA, for their tireless efforts toward improving the emotional recovery of our patients.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Conflicts of interest: none.

References

- [1].Fakhry SM, Ferguson PL, Olsen JL, Haughney JJ, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ. Continuing trauma: the unmet needs of trauma patients in the postacute care setting. Am Surg 2017;83(11):1308–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].American College of Surgeons and Committee on Trauma. Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. American College of Surgeons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brunet A, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, et al. The peritraumatic distress inventory: a proposed measure of PTSD criterion A2. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(9):1480–5. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2003;129(1):52–73. 10.1037//0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thomas É, Saumier D, Brunet A. Peritraumatic distress and the course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a meta-analysis. Can J Psychiatry 2012;57(2):122–9. 10.1177/070674371205700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nishi D, Matsuoka Y, Noguchi H, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the peritraumatic distress inventory. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31(1):75–9. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nishi D, Usuki M, Matsuoka Y. Peritraumatic distress in accident survivors: an indicator for posttraumatic stress, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and posttraumatic growth In: Ovuga E, editor. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders in a Global Context. 2012. p. 97–112. InTech. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ruggiero KJ, Davidson TM, Bunnell BE, Maples-Keller JL, Fakhry S. Trauma resilience and recovery program: a stepped care model to facilitate recovery after traumatic injury. Int J Emerg Ment Health 2016;18(2):25 10.4172/1522-4821.C1.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA 1999;282(18):1737–44. 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]