Abstract

Objective

To investigate how women experience the initial period of a new pregnancy after suffering recurrent miscarriage (RM).

Design

A qualitative study, nested within a randomised controlled feasibility study of a coping intervention for RM, used semi-structured face-to-face interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using a thematic network approach.

Setting

Participants were recruited from the Recurrent Miscarriage Clinic and Early Pregnancy Unit in two tertiary referral hospitals in the UK.

Participants

14 women with RMs and who had previously participated in the randomised controlled trial (RCT) feasibility component of the study were recruited.

Results

Seven organising themes emerged from the data: (1) turmoil of emotions, (2) preparing for the worst, (3) setting of personal milestones, (4) hypervigilance, (5) social isolation, (6) adoption of pragmatic approaches, (7) need for professional affirmation.

Conclusions

The study established that for women with a history of RM, the waiting period of a new pregnancy is a traumatic time of great uncertainty and emotional turmoil and one in which they express a need for emotional support. Consideration should be given to the manner in which supportive care is best delivered within the constraints of current health service provision.

Trial registration number

Keywords: recurrent miscarriage; adaptation, psychological; anxiet; pregnancy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This qualitative study addresses a gap in the literature, providing new and detailed data on how women experience the initial period of a new pregnancy after recurrent miscarriage (RM).

Qualitative face-to-face interviews enabled the exploration of this sensitive time period, giving participants the opportunity to convey their personal experiences.

While every effort was made to support the recruitment of a diverse sample to this study, the UK setting may limit extrapolation to other national and cultural contexts.

The purposive sampling strategy enabled an inclusive approach to data collection from the ethnicities represented in the main feasibility study sample.

Introduction

Miscarriage is the most common adverse outcome of pregnancy.1 It has been defined as the spontaneous demise of a pregnancy before the fetus reaches viability, therefore the term includes all pregnancy losses from the time of conception until 24 weeks of gestation.2 Recurrent miscarriage (RM) is currently defined as the loss of three or more consecutive pregnancies within the UK.3 However, other countries have adopted different definitions and the recently published European Society Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) guideline concludes that a diagnosis of RM could be considered after the loss of two or more pregnancies.2 The prevalence of RM is significantly lower than sporadic miscarriage, but the exact occurrence is difficult to estimate.2 When defined as the loss of three or more consecutive pregnancies, then it is proposed that 1% of couples who are trying to conceive are affected.3 However, the recently published ESHRE guidelines suggest that at least 1%–2% of couples experience recurrent pregnancy loss.2

This repeated and unintentional loss of pregnancy has been described as a distinct disease entity4–6 given that the observed incidence of RM is much higher than would be expected to occur by chance alone. The ESHRE guideline on the recommended treatment and investigation of recurrent miscarriage highlights the lack of evidence-based investigations and treatments available for this condition.2 Consistent with other guidelines,3 it highlights the need to ensure care is tailored to the psychological needs of couples. While the loss of any desired pregnancy ending in miscarriage is a profound and negative life event, RM represents an extremely distressing condition that can be both physically and emotionally traumatising. The repetitive nature of recurrent pregnancy loss may intensify the grief and distress experienced, delivering a significant emotional impact on those affected.2 The experience can evoke intense feelings surrounding a lost baby, a lost future child and a lost motherhood.7

Numerous studies have investigated emotional morbidity in women in the period immediately following miscarriage.8–10 More recently, a study by Kolte et al 11 concluded that increased levels of psychological distress and major depression are significantly more common among women with RM compared with women trying to achieve pregnancy who had not experienced this. This corresponds with the findings from previous studies, investigating emotional morbidity in women with recurrent pregnancy loss, which indicated that increased levels of anxiety and depression are often experienced throughout subsequent pregnancies.12 13

The early stages of a new pregnancy when confirmation by ultrasound scan of an ongoing and viable pregnancy is awaited represent a particularly challenging period for women affected by RM due to their anxiety that they will experience a further miscarriage.14

Medical waiting periods have been defined as those during which patients wait for test results that could be potentially threatening to their well-being.15 These waiting periods appear to have a distinct emotional signature. Psychological stress reactions are present and build from the start of any waiting period whereby anticipation of loss leads to further anxiety and prolonged psychological distress.16 Lazarus and Folkman17 proposed that the conditions that create stressful situations are particularly applicable to medical waiting periods. These characteristics include waiting for an outcome that can have negative consequences of significant impact on the individual, and the fact that it is not possible to change, control or predict the outcome. These stressors are uniquely characteristic of the waiting period of a new pregnancy after RM.

In the context of pregnancy after RM, the waiting period generally refers to the first 12 weeks of a pregnancy, although the actual length can vary between women and is often dependent on the timing of their previous miscarriages. However, a scan at 12 weeks gestation confirming viability is associated with a greater than 95% chance18 of an ongoing pregnancy and this reassurance can be considered to mark the end of the waiting period.

Published research data assessing the psychological morbidity associated with the difficult waiting period of a new pregnancy are scarce; however, a qualitative study exploring the experiences and coping strategies of women during the initial waiting period (weeks 1–12) of pregnancy after miscarriage revealed extreme anxiety about pregnancy outcome.14 As the number of previous miscarriages increased, women with RM felt extremely anxious about the pregnancy outcome, proposing that this uncertainty grew after each miscarriage and their coping was orientated towards presumed failure (a further miscarriage). Another study by Hutti et al 19 has suggested that instead of experiencing this period as a time of ‘joyful anticipation,’ couples who have previously experienced recurrent pregnancy loss frequently experience increased levels of anxiety and worry.

Despite the emotional morbidity associated with the waiting period, many women who have experienced RM are not provided with support during this time and are left to cope alone with their anxiety. This is mainly because existing supportive interventions are labour intensive and expensive to provide, and as urgency is almost immediate, it may be difficult to provide support quickly. The limited data available make it difficult to promote and target the development of therapeutic support for women with RM during the early waiting stages of a new pregnancy. To improve psychological well-being during this challenging time, there is a need to develop a deeper and more extensive understanding of lived experiences.

The qualitative study presented in this paper was nested within a two-centre randomised controlled trial (RCT) feasibility study of a novel self-help intervention designed to support women with a history of RM to cope with the waiting period before confirmation of a new ongoing pregnancy.20 21 The design and methodology of this paper have been published elsewhere,20 and the results will be reported separately.

The aim of the presented paper was to develop a deeper understanding and detailed insight into the lived experience of women with repeated pregnancy loss during the early ‘waiting’ stages of a new pregnancy.

Methods

Design

This qualitative study was designed to develop a deeper understanding of the types of emotional reaction to the waiting period to target the development of psychological therapeutic support for this group of women.

Patient and Public Involvement

A Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) advisory group supported this research and met on a regular basis for the duration of this study. The group were involved with the design of the study and commented on any potential burden of participating in the study from a patient’s perspective. The group were involved with data interpretation, and at the end of the study commented on the findings and contributed to the dissemination plan.

Participants

The study population consisted of patients attending the Recurrent Miscarriage Clinic and the Early Pregnancy Unit in two tertiary referral hospitals in the South of England.

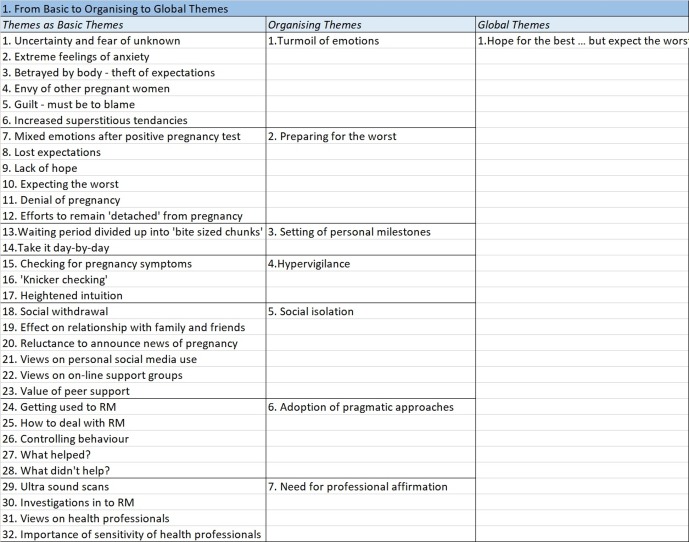

Between February 2014 and May 2016, 107 eligible women were invited to take part in a feasibility RCT testing a self-administered psychological support.20 21 Participants became eligible to take part in this qualitative study once they had completed the intervention. This included participants who had reached 12 weeks of pregnancy and those who had unfortunately experienced a further miscarriage. Care was taken to allow a suitable time period to elapse before participants were approached and invited to take part in an interview following a miscarriage. The aim of sampling was to collect perspectives from as diverse a group as possible. Selection characteristics considered in the purposive sampling strategy included study group in the RCT (control or intervention), ongoing pregnancy or miscarriage, ethnicity of participant, education level of participant and clinically important demographics such as age, comorbidity/medical conditions and previous live births. Of the 15 participants invited to take part in the qualitative element of the study, only one declined participation. Figure 1 illustrates the key demographic information of study participants.

Figure 1.

Key demographic information of study participants.

Data collection

Data were collected face-to-face, during semistructured interviews and took place at a convenient time and place for the participant. Recruitment was stopped when data saturation was achieved. All participants signed a consent form and were interviewed on an individual basis by the primary author. A topic guide was used to steer the general direction of the data collection, but participants were encouraged to speak freely about their perceptions and experiences of the waiting period of a new pregnancy to increase the understanding of the emotional reactions experienced during this time. The interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min and were audio-recorded then transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

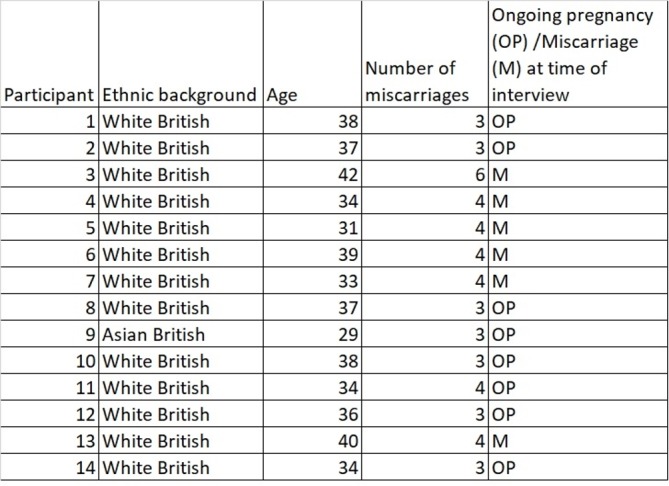

Evidence of reliability and validity in qualitative research methods is important to ensure the process of analysis is clear, transparent and trustworthy.22 ‘Thematic network analysis’23 was used as an analytic tool in this study to provide a robust and highly sensitive means of supporting thematic analysis and it facilitated an open and systematic approach. This method of analysis enabled the development of thematic networks that summarised the main themes apparent in the interview transcripts. As demonstrated in figure 2, the method simply provided a technique for breaking up the text into ‘Basic Themes’ (the most basic theme or lowest order theme), ‘Organising Themes’ (a middle-order theme that organises the Basic Themes into clusters of similar issues) and ‘Global Themes’ (which are macro themes that summarise and make sense of the clusters of lower order themes).

Figure 2.

A thematic network plan.

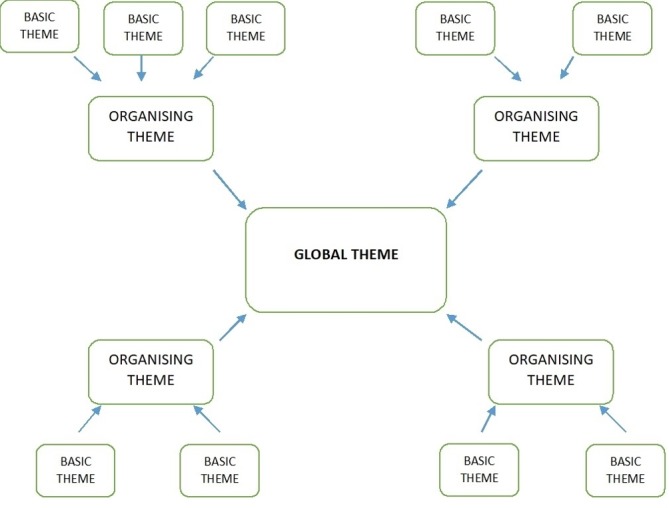

Thematic network analysis shares the key features of any hermeneutic analysis and is not a new method of analysis. However, the use of its web-like network as an organising principle and representational means helped to make explicit the procedures used in moving from text to interpretation of data.23 Figure 3 illustrates how transcribed data from this study were developed from basic themes into a single global theme.

Figure 3.

Development of basic, organising and global themes using thematic network analysis.

Transparency of data analysis was aided by the use of field notes and memos and by discussing the emerging themes with co-authors proficient in qualitative research analysis. Finally, basic and organising themes were grouped and refined following further analysis and discussion with co-authors.

Results

Analysis of the data identified seven ‘Organising Themes.’ These middle-order themes were the principles on which the global theme of ‘Hope for the best, but expect the worst’ was based and form the basis for the presentation of the results of this qualitative study.

The findings of this study and the illustrated quotes are representative of the perceptions and feelings of both groups of women in the RCT feasibility study (those who received the intervention and those who did not). Furthermore, although at the time of the interviews eight of the 14 women interviewed had ongoing pregnancies, they felt well able to reflect back on their experiences of the early waiting period with accuracy and did not feel their ongoing pregnancy affected their recollection of emotions at this time.

Organising theme 1: turmoil of emotions

The organising theme of ‘turmoil of emotions’ brings together the numerous reactions and feelings experienced by women with RM during the early stages of a new pregnancy while they are waiting for confirmation by ultrasound scan that it is ongoing. As outlined in box 1, the women experienced a plethora of emotions whereby any initial excitement caused by the positive pregnancy test was quickly overtaken by worry and fear that they would miscarry again.

Box 1. Turmoil of emotions.

Sometimes you will be happy, sometimes you will be sad, sometimes you will be angry. To me it always feels like a fire has been put out inside you, so you can smile, do whatever you want to, but your eyes just feel blank—Participant 6 (four miscarriages)

Because of how anxious I was, it was affecting everything. I was really anxious. I wasn’t sleeping properly, you worry about everything you eat, everything you drink. You just criticise and analyse everything you do all day long, all night long … Being anxious makes you anxious so it’s a real vicious circle— Participant 8 (three miscarriages)

The more you know what can go wrong, it becomes even more frightening … It is terrifying really, literally terrifying and that is how I feel— Participant 7 (four miscarriages)

The acute uncertainty of this situation appeared to compound the experience and the women’s distress as they continually ruminated on the outcome of their pregnancy because they were unable to accurately predict the outcome of the pregnancy. Instead, the women focused on what might happen and this meant it was difficult for them to use strategies to cope with the situation they found themselves in, as they had no definite idea of what would actually happen. The interviewees suggested that the situation was made worse by the ‘not knowing’ of what the outcome of the pregnancy would be. Once the uncertainty of the waiting period was over because the pregnancy was progressing as expected and they felt confident that their pregnancy would continue or because they unfortunately experienced a further miscarriage, then the negative emotional effects of uncertainty appeared to reduce.

All of the interviewees provided extremely powerful examples of the turmoil of emotions they had experienced during the waiting period with the majority of participants referring to the significant levels of anxiety and worry they experienced during this time. This was often overwhelming for them, affecting every aspect of their life and an emotion they were unable to escape from or forget. Accompanying the extreme levels of anxiety and the worry, several of the interviewees described emotions of fear and even terror at the situation they were in and the potential outcome of their pregnancy.

A number of participants remarked that a further notable emotion present throughout the waiting period was guilt, with the women blaming themselves entirely for their miscarriages. They spent time contemplating the lifestyle choices they had made in the past (eg, previous smoking/alcohol consumption or previous terminations of pregnancy), but they also felt guilty for letting down their partner and family at their inability to have a successful pregnancy.

Participants commonly expressed their shame at experiencing the emotions of jealousy and envy when they encountered other pregnant women or those with small babies, acknowledging the negative connotations of this emotion. They were, however, keen to point out that it was not a personal thing against the pregnant woman or new mother, rather that they wished it was them in that situation.

Organising theme 2: preparing for the worst

This organising theme conveys the emotional strategies used by the women to try to remain emotionally detached from the pregnancy, keeping themselves ‘in check’ because they did not want to let themselves become excited about the pregnancy (as outlined in box 2).

Box 2. Preparing for the worst.

It’s the not knowing and it’s the being unable to believe anything except the worst. I find I’m baffled by how pregnancies work these days, I’m kind of constantly surprised that people are having babies because my experience is so different … so now it’s impossible to believe that it’s going to be okay… I just came to the conclusion that the kindest thing I could do for myself was not to hope. The most likely outcome is that you are not going to have that addition to your family and so actually there’s no point picturing what life is going to be like because picturing it is exciting and it’s hoping for a future that probably isn’t going to be there. Hope just feels utterly naïve now—Participant 13 (four miscarriages)

I was very detached from the whole pregnancy … it was self-preservation kind of mode— Participant 11 (four miscarriages)

I think it’s a self-preservation because of what you’ve been through, but I was never like that with my daughter. It’s a learnt behaviour definitely … it’s almost like you can’t let yourself dream this might happen after wanting it so long— Participant 10 (three miscarriages)

I think me and my husband ended up trying not to think about it too much … you don’t want to get your hopes up so we’d be very cautious about even really talking about the positives in case it was bad news—Participant 14 (three miscarriages)

I need to be real and I prepare for the worst, but hope for the best and that’s almost like a protective shield around me— Participant 8 (three miscarriages)

A positive pregnancy test was met with feelings of anxiety, trepidation and negativity. It was a moment of realisation and the women described this as being back on the ‘roller coaster’ of pregnancy and its associated worry. Women were reluctant to share news of the pregnancy with family and friends because they were certain another miscarriage would occur. Interviewees also suggested that they suppressed any hope of a successful pregnancy and avoided thinking about a future with their unborn child. This appeared to be linked to a notion of self-preservation/protection. By attempting to prepare for the worst outcome (ie, a further miscarriage), they would be less upset if another miscarriage occurred.

Organising theme 3: setting of personal milestones

The interviewees placed huge importance on the need to attain personal milestones, using this as a method of navigating their way through the uncertainty of the waiting period (box 3). This was frequently achieved by breaking the pregnancy up into smaller time chunks, thinking of the first trimester in individual weeks, or even days, rather than as a whole period of time. In addition, the participants frequently recalled how they tried to live the early stages of a new pregnancy day-by-day, trying not to think too far ahead, living in the moment.

Box 3. Setting of personal milestones.

It’s 1 day at a time, that’s how we live 1 day at a time and that’s how we’ve lived since June and I don’t think it’s a bad thing because we are appreciating that emotions can change from day to day … rather than think about the birth we think about little hurdles … I try not to think too far ahead because I get overwhelmed with things— Participant 12 (three miscarriages)

It’s kind of like you are trying to climb a ladder and the first rung up is the twelve week scan, but at least if you have a 7 week scan and things are okay then you can stand on that rung and you know you’ve got that far— Participant 13 (four miscarriages)

As soon as I confirmed the pregnancy they told me that they would get me in for scans at 6, 8 and 10 weeks which helps because you’ve then got a 2 week marker to break up the 12 weeks. But I would say the anxiety massively increases up towards the scan … it build, builds, builds and then you have a scan and it drops so by the time I would go to a scan, especially the 6 week scan I was a complete mess and really struggling to hold it together, crying a lot and incredibly nervous, body full ofadrenaline and really, really anxious—Participant 3 (six miscarriages)

The women’s personal milestones often consisted of reaching and going past the gestation of their previous miscarriages, or achieving midwife or scan appointments.

During the interviews, participants were asked if anything had helped them cope with the waiting period and everyone referred to the value of reassurance from ultrasound scans and how they broke up this time into more manageable time chunks. Interestingly, however, all women commented that any optimism they felt after a positive scan was short-lived and feelings of anxiety soon started to re-emerge.

Organising theme 4: hypervigilance

Study participants frequently reported using observing strategies and hypervigilance to help them monitor their pregnancy symptoms, considering symptoms such as nausea, tiredness and breast tenderness as signs of an ongoing pregnancy (box 4). Many of the participants detailed checking as an obsession and something they could not help doing, wanting constantly to seek reassurance that their pregnancy was ongoing.

Box 4. Hypervigilance.

Knicker checking is a big obsession—Participant 5 (four miscarriages)

You are constantly monitoring your pregnancy symptoms, constantly. Do I feel the same as I did yesterday, are my ‘boobs’ still sore, do I need to go to the toilet more often or am I just drinking more? And you are constantly questioning every single twinge you feel and you are dying to get morning sickness so that you know you are pregnant— it’s just all consuming— Participant 3 (six miscarriages)

I was just constantly nauseous and if I wasn’t thinking about it I probably wouldn’t have realised that I was nauseous, because it wasn’t that bad. But I felt myself thinking about it and I wanted to feel that feeling sickness just so I know that something is happening. Until now every single time I go to the bathroom I have to check that I’m not bleeding and I’ve been doing it since the beginning of my pregnancy. I also spent quite a bit of money on pregnancy tests just to see … I did them almost everyday, but I couldn’t help it— Participant 9 (three miscarriages)

One of the most common early signs of miscarriage is the onset of vaginal bleeding or spotting. Many were so convinced that they were going to experience a further miscarriage that they frequently reported repeated visits to the toilet to check for the onset of vaginal bleeding. This could often amount to numerous toilet visits every hour.

Participants expressed that when pregnancy symptoms were more intense, then they felt more certain of an ongoing pregnancy; however, any fluctuation in symptoms increased their feelings of uncertainty and caused added emotional distress.

Organising theme 5: social isolation

This organising theme brings together the participants’ views on social interaction during the waiting period (box 5). Many reported that they felt isolated and lonely during this time. This was compounded by the fact that the women often isolated themselves from friends and family, reluctant to share the news of their pregnancy because they felt certain a further miscarriage would occur, therefore, there was no point in telling people. There was also an innate fear for several participants that sharing the news of their pregnancy in the early stages would tempt fate, and, as a result, they would experience a further miscarriage.

Box 5. Social isolation.

You want to tell people of course you do, but it makes you very private, very keep yourself to yourself — Participant 12 (three miscarriages)

It’s really difficult I think these days with Facebook, it’s really hard. I had to block a few people who put scan photos up or bump pictures. I found bump photos really hard because you think am I ever going to get there? Is that ever going to be me?— Participant 3 (six miscarriages)

I’ve never been so scared to go outside my front door because I might just bump in to someone who is pregnant. Pregnancy just seemed to be everywhere. It’s just one of those things where you become really heightened to it … and it was just awful, absolutely awful— Participant 8 (three miscarriages)

I didn’t want to speak to anybody, I didn’t want to face anybody— Participant 9 (three miscarriages)

There appeared to be a general withdrawal from social situations and social media, mainly due to the fear of forced social interaction with other pregnant women or those announcing news of a pregnancy. Compounding the degree of isolation was the fact that the women also appeared to feel safer and protected at home as they felt this environment might reduce the risk of miscarriage.

Organising theme 6: adoption of pragmatic approaches

This organising theme brings together some of the pragmatic and practical approaches participants used to try to manage the stress and uncertainty of the waiting period (box 6). The women referred to the fact that these practical approaches appeared to give them back some control in a situation where they had none.

Box 6. Adoption of pragmatic approaches.

The only thing that would help is my work … It took my mind away so I didn’t have time to think or dwell on think, so I think that was helpful— Participant 1 (three miscarriages)

I couldn’t just dwell in my own self-pity about how hard it all was. So yes distraction did help, so if work hadn’t given me distraction I would have gone and sought it. What made it better? Trying to be grateful, being distracted, really seriously just trying not to think about it—Participants 13 (four miscarriages)

You stop more and more things. So you’ll stop doing extra work, you’ll start relaxing more. You’ll stop doing some parts of your exercise, you’ll stop eating different foods. You go through the most illogical things in your head – if I stay calm it will be alright, if I just do walking it will be fine—Participant 6 (four miscarriages)

Pragmatic approaches to coping with the anxiety often consisted of simple distraction techniques and keeping busy. This was particularly evident in participants who already had children; however, work often provided a big distraction for employed participants. Other participants used avoidance (namely not allowing themselves to think about the pregnancy and blocking it out of their thought processes).

Commonly, the women tried to adapt their lifestyle to eliminate factors they felt could increase the risk of miscarriage such as reducing strenuous exercise or improving nutritional intake. Lifestyle adaptations could be more extreme with women giving examples of never opening the window on a car journey to avoid pollution from other cars or avoiding taking baths or showers in pregnancy.

Many of the participants referred to the value of accessing peer support as one of the most useful practical approaches they could adopt during this time. They believed only women who had experienced their situation truly understood the anxieties and challenges they faced. In most cases, peer support was accessed via on-line miscarriage support groups and forums.

Organising theme 7: need for professional affirmation

In the final organising theme, interviewees shared their views on the level of care they actually received from health professionals during the waiting period of their pregnancy and their perceptions of the type of care they would like to have received. Furthermore, they described the need for health professionals’ acknowledgement of the challenges they faced and the stress they experienced during the waiting period of a new pregnancy (box 7).

Box 7. Need for professional affirmation.

There is sometimes an absolute lack of understanding….I think generally the thing I would say to medical professionals is that they need to acknowledge that this person is probably going to be slightly damaged. Massive things don’t have to change just some realisation of what a new pregnancy means to a woman who has been through all those lost pregnancies—Participant 10 (three miscarriages)

It’s the whole if you’ve got no pain and you’ve got no blood you are fine, that’s what the GP would say—Participant 7 (four miscarriages)

The EPU (Early Pregnancy Unit) staff were more gutted than I was I think, they were lovely… they were all just rooting for me and it was really nice—Participant 13 (four miscarriages)

A recurrent theme in the interviews was a sense that health service provision was both limited and unsupportive, and the women felt that this demonstrated a lack of understanding of their needs during this testing time. Often the first health professional the woman accessed for support was their general practitioner (GP). While the degree of support offered by individual GPs varied, interviewees frequently spoke of the lack of support and understanding shown by them. Lack of empathy was considered one of the most upsetting aspects of their situation. All participants expressed the need to be cared for in a sensitive and understanding manner.

In general, the participants referred to the fact that contact with health professionals during the uncertainty of the waiting period was very important. They understood that the involvement of a health professional would not make a difference to the outcome of their pregnancy, but the contact helped them to feel more supported and they valued being able to share their concerns.

When an individual did receive empathetic care from a health professional, whether that was a GP or a nurse working in the Early Pregnancy Unit, then it made a positive difference to their emotional well-being.

Discussion

Awaiting confirmation of an ongoing, viable pregnancy after having experienced recurrent miscarriage is a traumatic period marked by an intense struggle between hope and despair, hypervigilance of pregnancy symptoms and bracing for another miscarriage. This all occurring in a context of social isolation and feeling relatively unsupported by health professionals. Nevertheless, women were shown to adopt diverse coping strategies aimed at achieving a state of cautious optimism that served to maintain hope while bracing for the possibility of failure.

The findings from this study provide further evidence that there is a need for provision of psychological support to women during the difficult waiting period of a new pregnancy after RM. It also offers new and previously unexplored insights into how women experience this challenging time.

The global theme identified in this study was that waiting is traumatic and a time in which the women hope for the best, but expect the worst. This global theme supports and expands on those reported by others. Previous research has demonstrated that women with a history of repeated pregnancy loss use coping strategies to ‘brace for the future,’ as a means of attempting to control their emotions and future emotions as much as possible to prepare for the worst outcome.14 This involved anticipating the negative feelings that a further miscarriage would cause and using bracing strategies such as not allowing themselves to think about a future with their unborn child and attempting to remain emotionally detached from the pregnancy. Behaviours similar to ‘bracing for the worst’14 have been reported in other studies that investigated pregnancy after previous perinatal loss, including ‘holding back emotions’24 and ‘emotional cushioning’25 which involves ‘compartmentalising the pregnancy and avoiding its emotional aspects for as long as possible.’25 The compelling evidence from this study provides further evidence of bracing adding to suggestions from previous studies14 that propose the need for further research to investigate the impact of bracing strategies on long-term bonding and attachment between child and parents.

All participants concurred that the uncertainty of the situation compounded their emotional upset. The uncontrollability and unpredictability of the waiting period seemed a particularly difficult aspect for them to cope with. The formative work of Lazarus and Folkman17 examined the processes of stress, appraisal and coping and identified the fact that both a lack of control over a situation and an inability to predict its outcome are potential stress-inducing factors. If the demands of a situation exceed the level of coping resources available to the person, then the affected individual is likely to experience stress, namely psychological (eg, anxiety, worry), physiological (eg, racing heart, tension) and behavioural responses (eg, insomnia).17 The participants in this study consistently commented that the uncertainty of the waiting period was itself a stressor eliciting emotional turmoil, some even commenting on the relief they felt when a further miscarriage occurred as they felt better able to cope with the grief of miscarriage than the uncertainty of the waiting period. Positive reappraisal coping has been shown to be useful and valuable coping strategy and a helpful tool to help sustain coping during periods of uncertainty.26 27 This type of coping might provide some respite from the prolonged and unrelenting stress that women with RM experience during the early stages of a new pregnancy and help to sustain their ability to cope during this challenging time. The RCT component of this study has investigated the use of a novel self-help coping intervention, the Positive Reappraisal Coping Intervention.21 28 Further research is planned to explore the role of the Positive Reappraisal Coping Intervention and how it appears to generate resilience in its users.

One organising theme described the strong ‘need for professional affirmation’ and perceptions of the level of care patients would like to receive. In a pioneering piece of work, Bradshaw29 presented a taxonomy of social need in which he acknowledged that the concept of need was both complex and imprecise. Furthermore, he emphasised the fact that need was relative and therefore needs identified by professional experts often differed from those felt by the individual. Certainly, a recurrent theme during the interviews was a sense that current health service provision for women with RM during the waiting period of a new pregnancy was both limited and unsupportive. Participants felt these gaps in support demonstrated a lack of understanding of their needs during this challenging time. The need for professional support and reassurance was generated at the actual moment of realisation that they were pregnant again, following the positive pregnancy test and in general was experienced towards the first health professional they would contact for support and advice (ie, their GP). While the degree of support offered by GPs varied individually, many women spoke of their disappointment at the lack of understanding and compassion shown to them. There was a general feeling that any health professional interaction that took place within a dedicated Early Pregnancy Unit environment was more sensitive to their needs, but that there was still room for improvement.

While this study builds on the results of other studies that have identified the importance of understanding and compassion from health professionals around the time of miscarriage,30 31 it specifically highlights the need for health professional support during the early stages of a new pregnancy after RM.

Clearly, consideration needs to be given to the most effective and appropriate ways in which health professionals can meet this demand for support, given the limited time constraints within which they work. GPs have time-limited consultations, often of less than 10 min per patient and similarly secondary care health professionals work within restricted clinic appointment times. It is not always feasible to address every aspect of the woman’s psychological needs during this time. For example, some women with recurrent miscarriage would prefer at least weekly reassurance ultrasound scans and others individual regular counselling sessions. However, the data from this study highlighted that in all cases, there was a sense among participants of the need to raise awareness within the health professional community of the potential emotional impact of the waiting period and the need for empathetic care. The participants acknowledged that they understood that the involvement of health professionals would not make a difference to the outcome of their pregnancy. Furthermore, the women understood that their emotional needs fluctuated during the waiting period and therefore it was difficult for GPs and other health professionals to address these needs specifically. However, similar to the findings of a study by Musters et al 10 that investigated supportive care for women with RM, women in this study noted that when health professionals took their emotional concerns seriously by listening to them and showing them understanding and empathy, then it made a positive difference to their emotional well-being. The ‘soft’ skills of compassion, empathy and understanding appeared to meet the need for support during the uncertainty of the waiting period.

This study has two main strengths; its development and protocol was guided by an active PPI advisory group and this ensured the patient’s perspective was central to the study. Second, the study addresses a gap in the literature and provides new and detailed qualitative data on how women experience the initial waiting period of a new pregnancy after RM. Study limitations included the fact that the qualitative study was nested within an RCT feasibility study20 21 and this was reflected in the choice of research methods selected. Furthermore, the majority of participants who took part in this study were of White British ethnicity, mainly due to the study sites in the South of England. A more varied ethnicity sample may have provided a more diverse and richer insight into the cultural effects of RM.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that for many women with RM, the waiting period of a new pregnancy is a time of great uncertainty and emotional turmoil and one in which they are likely to require emotional support.

Recurrent pregnancy loss has the potential to cause serious psychological effects including grief, anxiety and depression, and these emotional symptoms can affect every aspect of the woman’s life. RM is therefore much more than just a medical condition; its consequences are more profound and life changing, and the provision of supportive care should be central to the management of women who experience this distressing and frustrating condition.

This study reveals the thoughts and perceptions of women with a history of RM during the waiting period of a new pregnancy; the challenge remains for both clinicians and service providers to develop a service that meets the needs of these women given the complex and challenging times that the National Health Service (NHS) is experiencing. Recent NHS policy32 advocates the need to ensure health services are designed around patients, but on a more sustainable footing. This includes the use of technology and innovation to enable patients to take a more active role in their health. The next stage of this programme of research plans to investigate the potential use of technical innovation strategies as a method of providing much needed support to this vulnerable patient population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the women who kindly agreed to participate in this study and the members of the Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) group for their valuable input into this programme of research.

Footnotes

Contributors: SLB contributed to the design of the study, was responsible for obtaining ethical approval and liaised with the PPI group for this study. NM, CB, JB, EK-R and YCC contributed to the design of the study. SLB and EK-R coded and analysed all the transcripts. All authors were involved in interpretation of the data. SLB wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors were involved in subsequent revision. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Health Research, UK (award reference number CDRF-2012-03-004). The study was sponsored by University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: A favourable opinion was received from National Research Ethics committee, South Central – Hampshire A (13/SC/0506).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This research is part of a PhD study by SLB. The PhD will be available via the University of Southampton depository.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Simmons RK, Singh G, Maconochie N, et al. . Experience of miscarriage in the UK: qualitative findings from the National Women’s Health Study. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1934–46. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. ESHRE. Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Guideline of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. RCOG. The investigation and treatment of couples with recurrent first-trimester and second-trimester miscarriage, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rai R, Regan L. Seminar: Recurrent miscarriage. The Lancet 2006;368:601–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christiansen OB, Steffensen R, Nielsen HS, et al. . Multifactorial Etiology of Recurrent Miscarriage and Its Scientific and Clinical Implications. 2008:66;257–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larsen EC, Christiansen OB, Kolte AM, et al. ; New insights into mechanisms behind miscarriage. 11, 2013. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ockhuijsen HD, van den Hoogen A, Boivin J, et al. . Pregnancy after miscarriage: balancing between loss of control and searching for control. Res Nurs Health 2014;37:267–75. 10.1002/nur.21610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Craig M, Tata P, Regan L. Psychiatric morbidity among patients with recurrent miscarriage. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2002;23:157–64. 10.3109/01674820209074668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Swanson KM, Chen HT, Graham JC, et al. . Resolution of depression and grief during the first year after miscarriage: a randomized controlled clinical trial of couples-focused interventions. J Womens Health 2009;18:1245–57. 10.1089/jwh.2008.1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Musters AM, Koot YE, van den Boogaard NM, et al. . Supportive care for women with recurrent miscarriage: a survey to quantify women’s preferences. Hum Reprod 2013;28:398–405. 10.1093/humrep/des374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kolte AM, Olsen LR, Mikkelsen EM, et al. . Depression and emotional stress is highly prevalent among women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod 2015;30:777–82. 10.1093/humrep/dev014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Magee PL, Macleod AK, Tata P, et al. . Psychological distress in recurrent miscarriage: The role of prospective thinking and role and goal investment. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2003;21:35–47. 10.1080/0264683021000060066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lok IH, Neugebauer R. Psychological morbidity following miscarriage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;21:229–47. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ockhuijsen HD, Boivin J, van den Hoogen A, et al. . Coping after recurrent miscarriage: uncertainty and bracing for the worst. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2013;39:250–6. 10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boivin J, Lancastle D. Medical waiting periods: imminence, emotions and coping. Womens Health 2010;6:59–69. 10.2217/whe.09.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osuna EE. The psychological cost of waiting. J Math Psychol 1985;29:82–105. 10.1016/0022-2496(85)90020-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping / Richard S. Lazarus, Susan Folkman. New York: Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tong S, Kaur A, Walker SP, et al. . Miscarriage risk for asymptomatic women after a normal first-trimester prenatal visit. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:710–4. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318163747c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hutti MH, Armstrong DS, Myers JA, et al. . Grief intensity, psychological well-being, and the intimate partner relationship in the subsequent pregnancy after a perinatal loss. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2015;44:42–50. 10.1111/1552-6909.12539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bailey S, Bailey C, Boivin J, et al. . A feasibility study for a randomised controlled trial of the Positive Reappraisal Coping Intervention, a novel supportive technique for recurrent miscarriage. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007322 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bailey S. A feasibility and acceptability study and a qualitative process evaluation of a coping intervention for recurrent miscarriage. University of Southampton, PhD thesis 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amankwaa L. Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Cult Divers 2016;23:121–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research 2001;1:385–405. 10.1177/146879410100100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cĵté-Arsenault D, Dombeck MT. Maternal assignment of fetal personhood to a previous pregnancy loss: relationship to anxiety in the current pregnancy. Health Care Women Int 2001;22:649–65. 10.1080/07399330127171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Côté‐Arsenault D, Donato K. Emotional cushioning in pregnancy after perinatal loss. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2011;29:81–92. 10.1080/02646838.2010.513115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1207–21. 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00040-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Manne S, Ostroff J, Fox K, et al. . Cognitive and social processes predicting partner psychological adaptation to early stage breast cancer. Br J Health Psychol 2009;14:49–68. 10.1348/135910708X298458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lancastle D, Boivin J. A feasibility study of a brief coping intervention (PRCI) for the waiting period before a pregnancy test during fertility treatment. Hum Reprod 2008;23:2299–307. 10.1093/humrep/den257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bradshaw J. The concept of social need: McClachlan G, Problems and Progress. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meaney S, Corcoran P, Spillane N, et al. . Experience of miscarriage: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e011382 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Norton W, Furber L. An exploration of how women in the UK perceive the provision of care received in an early pregnancy assessment unit: an interpretive phenomenological analysis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e023579 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. NHS England. Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.