Abstract

Objectives

Low birth weight (BW) is a general symbol of inadequate intrauterine conditions that elicit abnormal fetal growth and development. The aim of current study is to investigate the relationship between low BW and thinness or severe obesity during maturation.

Design

A large-scale cross-sectional population-based survey.

Setting

134 kindergartens and 70 elementary schools.

Participants

70 284 Chinese children aged 3–12 years.

Outcome measures

International Obesity Task Force body mass index (BMI) cut-offs were used to define grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3 thinness, overweight, obesity and severe obesity. Multinomial logistic regression was used to estimate the association between BW and BMI category.

Results

A total of 70 284 children participated in the survey. The percentage of grade 1 thinness and severe obesity in children with low BW is significantly higher than that in children with normal BW (p<0.05). Low BW was associated with an increased risk of grade 1 thinness (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.38 to 1.75), grade 2 thinness (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.64), grade 3 thinness (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.63 to 2.42) and severe obesity (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.55) but was not associated with obesity (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.06).

Conclusion

There is a positive association between low BW and thinness or severe obesity risk.

Keywords: birthweight, obesity, thinness, children

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a large population-based cross-sectional survey with a representative, multistage proportional cluster sampling.

Low birth weight (BW) was found to be associated with an increased risk of grade 1 thinness, grade 2 thinness, grade 3 thinness and severe obesity, rather than overweight or obesity.

Height/weight and BW data were collected by self-reported questionnaires in a cross-sectional study.

Introduction

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious global public health challenges.1 Furthermore, obesity in childhood may lead to short-term morbidity and to subsequent adverse consequences across the individual’s lifespan and his or her subsequent generation.1 Growing evidence indicates that perinatal characteristics have been recognised as contributing factors to the obesity epidemic.2 Birth weight (BW) is frequently used as an indicator of the conditions experienced in utero, which contribute to the newborn baby’s survival, health, growth and development.3 4 Lower BW is a general symbol of inadequate intrauterine conditions that elicit abnormal fetal growth and development.5 Based on the findings of numerous studies, low BW (BW <2500 g) has been shown to trigger various short-term and long-term health issues, especially for birth injuries, delayed motor development, delayed cognitive and social skills, obesity and chronic diseases.4 6

A great number of studies have indicated that high BW is associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity.6–9 Nevertheless, the conclusions drawn by studies evaluating the associations between low BW and obesity appear to be controversial. Some studies suggest that low BW correlates with a significantly elevated risk of obesity,10 11 while some other studies contradict this result, reporting that low BW is unrelated to or protective against overweight and/or obesity.6 12 13 However, these studies only assess the effect of BW on childhood overweight or obesity but ignored childhood thinness.

Because of the absence of evidence regarding the relationship between BW and thinness and the inconsistent conclusions regarding the relationship between BW and overweight or obesity, in this large population-based observational study, we aimed to examine the relationship between BW and the risk of obesity and placed extra emphasis on the effect of thinness in children aged 3–12 years from seven districts of Shanghai.

Methods

Study design and quality control

Our study was a school-based cross-sectional population study and was part of a governmental population survey of autism spectrum disorders. Multistage, stratified clustered random sampling was conducted in children aged 3–12 years in Shanghai, China, and related baseline data were collected from 134 kindergartens and 70 elementary schools in June 2014. Details of the sample size, sampling and quality control process have been described previously.14 15 The 17 districts of Shanghai were stratified into eight urban districts in the central area and in nine suburban areas according to the geographical and social population distributions; people living in urban and suburban districts were defined as urban and suburban residents. EpiData V.3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) was used for data inputting, and a logical error check was applied. We also repeated data entry by randomly sampling 15% of the questionnaires to ensure consistency. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning.

Measurements

We used growth questionnaires for collecting information about children’s families and social environments. Teachers distributed questionnaires to students, asked students to take the questionnaire home and have their parents fill in the information, then the teachers collected the completed questionnaires and returned them to the investigator. Parents provided the following information about their children: age, sex, weight, height, BW, education level, and so on, by self–report. Participants with complete BW, weight and height data constituted the final sample. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by the square of height (kg/m2) and classified as grade 3 thinness, grade 2 thinness, grade 1 thinness, overweight, obesity and severe obesity, according to the International Obesity Task Force age-specific and sex-specific cut-off points, of which BMI cut-offs equal to 16.0, 17.0, 18.5, 25.0, 30.0 and 35.0 kg/m2, respectively, at age 18 years.16

BW was divided into the low BW group (neonates weighing <2500 g at birth, irrespective of gestational age), the normal BW group (neonates weighing 2500–4000 g at birth, irrespective of gestational age) and the high BW group (neonates weighing ≥4000 g at birth, irrespective of gestational age).

Neonatal characteristics, including gestational weeks (<37, 37–42 and ≥42 weeks), normal delivery (yes or no), single-child family (yes or no), maternal history of abortion (yes or no), asphyxia (lack of oxygen at birth, yes or no) and infant feeding patterns (breast feeding exclusively, formula feeding exclusively and mixed feeding) were considered as potential prenatal confounding factors.6 17 Moreover, parental socioeconomic characteristics were considered as follows: family income was divided into three categories (low: <¥50 000 per year, middle: ¥50 000–2 00 000 per year and high: ≥¥200 000 per year) according to the definitions of social science,18 parental education (low: illiterate, primary school and junior school; middle: high school, technical school and college; high: undergraduate, master and doctor) and residence location (urban districts: Yangpu, Xuhui and Jing’an; suburban districts: Minhang, Pudong, Fengxian and Chongming).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean values with SDs, and Student’s t-test was carried out for group comparisons. Categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers with relative frequencies (%). The linear-by-linear trend test was performed to detect the distribution of different BMI categories between low BW and normal BW, and intersubgroup differences were examined using Pearson’s χ2 test. Multinomial logistic regression was used to estimate the relationship between BW and the risk of childhood thinness and obesity with normal weight as a reference group. Model 1 adjusted for the basic characteristics, age and gender, which were all influence factors of BMI category. Also, neonatal characteristics were reported to be associated with both BW and BMI category and thus were adjusted as a confounder in model 2. Socioeconomic characteristics could reflect the environment and nutritional status to some extent and were further adjusted in model 3. All confounding variables enter into the multinomial regression model. OR and 95% CI were obtained by using the multiple models. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics V.22. The criterion for statistical significance was 0.05 by two-tailed test.

Patient and public involvement

Parents were informed about questions and data of the survey before filling in the questionnaires, and were not involved the design, recruitment and conduct of the study; the results will be disseminated to participants as required.

Results

In total, 84 075 questionnaires were distributed and 81 384 completed questionnaires were returned with a response rate of 96.80%. Complete data regarding weight, height and BW were available for 70 284 children. A total of 3359 children were born with low BW and 59 356 children were born with normal BW: 32 629 boys (52.03%) and 30 086 girls (47.97%) aged 3–12 years. Sex-specific variables, such as growth (age, BMI category and BW), neonatal characteristics (pregnancy term, breast feeding, normal delivery, number of children, abortion and asphyxia) and parental socioeconomic characteristics (residence, family income and parental education), are described in detail in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| Variables | No | Boys, n (%) | Girls, n (%) | χ2 | P value |

| Number | 62 715 | 32 629 (52.0) | 30 086 (48.0) | ||

| Age (year) | 2.76 | 0.948 | |||

| 3 | 2006 | 1023 (3.1) | 983 (3.3) | ||

| 4 | 8186 | 4250 (13.0) | 3936 (13.1) | ||

| 5 | 8481 | 4434 (13.6) | 4047 (13.5) | ||

| 6 | 8237 | 4286 (13.1) | 3951 (13.3) | ||

| 7 | 8133 | 4260 (13.1) | 3873 (12.9) | ||

| 8 | 8540 | 4431 (13.6) | 4109 (13.7) | ||

| 9 | 7494 | 3876 (11.9) | 3618 (12.0) | ||

| 10 | 6477 | 3402 (10.4) | 3075 (10.2) | ||

| 11 | 5161 | 2667 (8.2) | 2494 (8.3) | ||

| BMI category | 803.87 | <0.001 | |||

| Grade 3 thinness | 1637 | 752 (2.3) | 885 (2.9) | ||

| Grade 2 thinness | 2071 | 938 (2.9) | 1133 (3.8) | ||

| Grade 1 thinness | 6568 | 3001 (9.2) | 3567 (11.9) | ||

| Normal | 38 831 | 19 502 (59.8) | 19 329 (64.3) | ||

| Overweight | 8614 | 5292 (16.2) | 3322 (11.0) | ||

| Obesity | 2514 | 1696 (5.2) | 818 (2.7) | ||

| Severe obesity | 2480 | 1448 (4.4) | 1032 (3.4) | ||

| Birth weight category (g) | 19.88 | <0.001 | |||

| <2500 | 3359 | 1622 (5.0) | 1737 (5.8) | ||

| 2500–4000 | 59 356 | 31 007 (95.0) | 28 349 (94.2) | ||

| Neonatal characteristics | |||||

| Pregnancy term (weeks) | 19.22 | <0.001 | |||

| <37 | 3854 | 2135 (6.5) | 1719 (5.7) | ||

| 37–42 | 56 238 | 29 106 (89.2) | 27 132 (90.2) | ||

| ≥42 | 2035 | 1063 (3.3) | 972 (3.2) | ||

| Missing | 588 | 325 (1.0) | 263 (0.9) | ||

| Feeding patterns (<4 months) | 4.59 | 0.101 | |||

| Breast feeding | 30 716 | 15 925 (48.8) | 14 791 (49.2) | ||

| Formula feeding | 9959 | 5119 (15.7) | 4840 (16.1) | ||

| Mixed feeding | 21 612 | 11 363 (34.8) | 10 249 (34.1) | ||

| Missing | 428 | 222 (0.7) | 206 (0.7) | ||

| Normal delivery | 1.23 | 0.267 | |||

| Yes | 30 054 | 15 563 (47.7) | 14 491 (48.2) | ||

| No | 32 226 | 16 831 (51.6) | 15 395 (51.2) | ||

| Missing | 435 | 235 (0.7) | 200 (0.7) | ||

| One-child family | 34.94 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 43 207 | 22 748 (69.7) | 20 459 (68.0) | ||

| No | 15 665 | 7816 (24.0) | 7849 (21.6) | ||

| Missing | 3843 | 2065 (6.3) | 1778 (5.9) | ||

| Abortion | 3.16 | 0.076 | |||

| Yes | 14 849 | 7818 (24.0) | 7031 (23.4) | ||

| No | 47 401 | 24 561 (75.3) | 22 840 (75.9) | ||

| Missing | 465 | 250 (0.8) | 215 (0.7) | ||

| Asphyxia | 45.15 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 2146 | 1269 (3.9) | 877 (2.9) | ||

| No | 59 732 | 30 916 (94.8) | 28 816 (95.8) | ||

| Missing | 837 | 444 (1.4) | 393 (1.3) | ||

| Socioeconomic characteristics | |||||

| Area | 3.20 | 0.074 | |||

| Suburban | 49 231 | 25 709 (78.8) | 23 522 (78.2) | ||

| Urban | 13 371 | 6866 (21.0) | 6505 (21.6) | ||

| Missing | 113 | 54 (0.2) | 59 (0.2) | ||

| Income | 4.92 | 0.086 | |||

| Low | 16 762 | 8811 (27.0) | 7951 (26.4) | ||

| Middle | 34 442 | 17 898 (54.9) | 16 544 (55.0) | ||

| High | 10 279 | 5261 (16.1) | 5018 (16.7) | ||

| Missing | 1232 | 659 (2.0) | 573 (1.9) | ||

| Mother’s education level | 48.07 | <0.001 | |||

| Low | 17 541 | 9485 (29.1) | 8056 (26.8) | ||

| Middle | 24 365 | 12 435 (38.1) | 11 930 (39.7) | ||

| High | 16 972 | 8629 (26.4) | 8343 (27.7) | ||

| Missing | 3837 | 2080 (6.4) | 1757 (5.8) | ||

| Father’s education level | 33.79 | <0.001 | |||

| Low | 15 357 | 8280 (25.4) | 7077 (23.5) | ||

| Middle | 24 305 | 12 467 (38.2) | 11 838 (39.3) | ||

| High | 19 196 | 9805 (30.0) | 9391 (31.2) | ||

| Missing | 3857 | 2077 (6.4) | 1780 (5.9) | ||

The boldfaced number means P<0.05 for chi-square test.

BMI, body mass index.

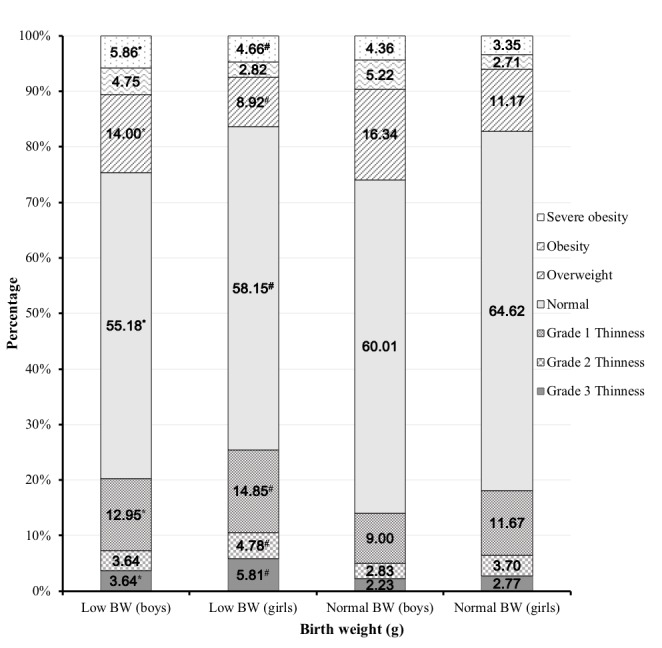

The distribution of different BMI categories between low BW and normal BW was examined by linear-by-linear trend test and the chi-square tests value was 36.98 (p<0.001). Detailed information is shown in figure 1. For boys, the respective percentage of grade three thinness (3.64%, 95% CI 3.55% to 3.73%, vs 2.23%, 95% CI 2.21% to 2.25%, p<0.05), grade two thinness (3.64%, 95% CI 3.55% to 3.73%, vs 2.83%, 95% CI 2.81% to 2.85%, p<0.05), grade one thinness (12.95%, 95% CI 12.79% to 13.11%, vs 9.00%, 95% CI 8.97% to 9.03%, p<0.05) were higher in the low BW group than those in the normal BW group; in contrast, the respective percentage of overweight (14.00%, 95% CI 13.83% to 14.17%, vs 16.34%, 95% CI 16.30% to 16.38%, p>0.05), obesity (4.75%, 95% CI 4.65% to 4.85%, vs 5.22%–95% CI 5.20% to 5.24%, p>0.05) were not statistically significant but severe obesity (5.86%, 95% CI 5.75% to 5.97%, vs 4.36%, 95% CI 4.34% to 4.38%, p<0.05) was higher in low BW group compared with normal group (p<0.05). Meanwhile, the percentage of severe obesity and grade three thinness were relatively higher in low BW group compared with the normal BW group (p<0.05), which shows a U-shape. The pattern is similar in girls; the percentage of grade three thinness (5.81%, 95% CI 5.70% to 5.92% vs 2.77%–95% CI 2.75% to 2.79%, p<0.05), grade two thinness (4.78%, 95% CI 4.68% to 4.88% vs 3.70%, 95% CI 3.68% to 3.72%, p<0.05), grade one thinness (14.85%, 95% CI 14.68% to 15.02% vs 11.67%, 95% CI 11.63% to 11.71%, p<0.05) were higher, but severe obesity (4.66%, 95% CI 4.56% to 4.76% vs 3.35%, 95% CI 3.33 to 3.37, p<0.05) was lower in the low BW group. However, overweight (8.92%, 95% CI 8.79% to 9.05%, vs 11.17%, 95% CI 11.13% to 11.21%, p<0.05) and obesity (2.82%, 95% CI 2.74% to 2.90%, vs 2.71%, 95% CI 2.69 to 2.73, p>0.05) showed no statistical difference between the groups.

Figure 1.

Percentage of thinness, overweight, obesity and severe obesity between low BW and normal BW. *Statistically significant difference between low BW and normal BW in boys (χ2 test, p<0.05); #Statistically significant difference between low BW and normal BW in girls (χ2 test, p<0.05). BW, birth weight.

Multinomial logistic regression was used to further determine the relationship between BW and thinness, overweight and obesity after adjusting for potential confounders. As shown in table 2, an initial analysis was performed in model 1, adjusting for only age and gender variables. The results showed that low BW is significantly associated with a higher risk of both thinness (grade 3 thinness: OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.82 to 2.56; grade 2 thinness: OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.70; grade 1 thinness: OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.34 to 1.65) and severe obesity (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.38 to 1.90), but was not associated with overweight (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.00) or obesity (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.26). In addition, model 2 is further adjusted for neonatal characteristics based on model 1, and model 3 is characterised by additional adjustments for socioeconomic variables based on model 2. Still, children with low BW are more likely to have grade 1 thinness (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.38 to 1.75), grade 2 thinness (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.64) and especially grade 3 thinness (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.63 to 2.42); the pattern is consistent in the three models. Low BW remained a statistically significant predictor of severe obesity (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.55) but was not associated with obesity (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.06).

Table 2.

Association between low birth weight and thinness, overweight, obesity and severe obesity by multinomial logistic regression models

| n | Grade 3 thinness | Grade 2 thinness | Grade 1 thinness | Overweight | Obesity | Severe obesity | |

| Model 1 | 62 715 | 2.16 (1.82 to 2.56)* | 1.43 (1.20 to 1.70)* | 1.49 (1.34 to 1.65)* | 0.89 (0.80 to 1.00) | 1.05 (0.87 to 1.26) | 1.62 (1.38 to 1.90)* |

| Model 2 | 56 909 | 2.12 (1.74 to 2.59)* | 1.35 (1.10 to 1.65)* | 1.52 (1.35 to 1.72)* | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.00) | 1.00 (0.81 to 1.25) | 1.43 (1.18 to 1.75)* |

| Model 3 | 55 600 | 1.99 (1.63 to 2.42)* | 1.34 (1.10 to 1.64)* | 1.56 (1.38 to 1.75)* | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.99)* | 0.85 (0.67 to 1.06) | 1.27 (1.03 to 1.55)* |

Normal BMI as the reference group.

Model 1: adjusted for age and gender.

Model 2: adjusted for age, gender and neonatal characteristics (pregnant term, feeding pattern, delivery mode, one child, abortion and asphyxia).

Model 3: adjusted for age, gender, neonatal characteristics (pregnant term, feeding pattern, delivery mode, one child, abortion and asphyxia) and socioeconomic characteristics (urbanicity, parental education and family income).

*P value <0.05.

BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

In the present study, we reported a bidirectional effect of low BW, increasing the risk of grade 3 thinness and severe obesity.

Some studies have assessed the relationship between low BW and the risk of childhood obesity, but the results were controversial.6 19–23 In a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 11 studies, pooled estimates for low BW (<2500 g) revealed no association with obesity (pooled OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.08) using normal BW (2500–4000 g) as the reference category.6 Another systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 studies found that low BW was associated with a reduced risk of childhood obesity (pooled OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.76).19 With regard to long-term risk of overweight and obesity, two previous papers have suggested a positive association with low BW, including a population-based cross-sectional survey among Chinese adults (obesity: OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.43)11 and an observational study among older women in Sweden (obesity: OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.26).10 On the contrary, a large, full-range BW study reported that children with a BW of <2500 g were protected against overweight or obesity from 6 months to 3 years of life, but this association disappeared among boys at 2 years of age.21 Our study highlighted the association between low BW and increased risk of severe obesity rather than overweight or obesity among Chinese children aged between 3 and 12 years. An age-specific effect of low BW on obesity might address some of the primary reasons why previous studies have drawn contrasting conclusions. In a Swedish cohort with 285 children with marginally low BW (2000–2500 g) and 95 children with normal BW, no increased risk of overweight or obesity was observed by up to 7 years (BMI 0.47 kg/m2 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.76) lower compared with controls).24 Another possible explanation might be the potential of growth have not been fully developed among those children with low BW. Not all children with low BW undergo catch-up growth, and different growth patterns might exist. Special attention should be payed among those children with low BW in future cohort studies.

It was difficult to explain the particular pattern between grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3 thinness and various BW groups. In a follow-up study in two rural Shaanxi counties of Northwest China, low BW was not related with boys’ obesity or thinness rates (adjusted OR 2.91, 95% CI 0.95 to 8.93) but was significantly correlated with increased risk of thinness among girls (adjusted OR 4.41, 95% CI 1.77 to 10.97).25 Our study confirmed the association and further demonstrated that low BW is associated with an increased risk of subsequent grade 3 thinness, followed by grade 1 thinness and then grade 2 thinness after adjusting for confounding variables. On the other hand, high BW exerted a protective effect on grade 2 thinness, followed by grade 1 thinness, then grade 3 thinness. Most notably, low BW was a risk factor for grade three thinness, as well as severe obesity. We hypothesised that the relationship between BW and thinness, overweight or obesity risk was not directly linear, whereas the relationship between low BW and BMI was U-shaped. Low BW was an adverse perinatal environment factor that predicts changes to the central regulatory mechanism linked with negative influences on metabolism and BMI.26 Thus, children with low BW, accompanied by poor childhood weight outcomes, should receive more public health attention.

Several studies have indicated that abnormal BW was an important risk factor for metabolic disease occurrence, especially for hypertension, type 2 diabetes, abdominal obesity and other chronic diseases later in life.11 27–29 A proposed explanation for the relationship between BW and postnatal growth was through the concept of ‘developmental origins of health and disease’, which stated that environmental cues during critical periods of life lead to predictive adaptive responses that shape tissue development and metabolic pathways, thereby permanently affecting long-term health and disease risk.30 Our epidemiological observations might have implications for understanding intrauterine environmental influences during early development and the relationship of BW with later risk of thinness and obesity.

Strengths and limitations

Our study recruited children from low-income to high-income families across seven districts of the Shanghai area by a large, representative, multistage proportional cluster sampling. We were able to assess the relationship between low BW and risk of childhood thinness, obesity or severe obesity using a large sample size (n=70 284) of children with low BW (4.61%). What’s more, we provided a comprehensive profile of the distribution of overall BMI status, including grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3 thinness; normal weight; overweight; obesity and severe obesity in low and normal BW groups. As for the potential confounding variables associated in the multinomial logistic regression, we took a broad range of predictors into consideration, from prenatal to postnatal.

However, there were several limitations in our study. First, the cross-sectional nature precluded us from making cause-and-effect inferences and observing continuous age-effects and long-term effects. Because aetiology of thinness and obesity could not be drawn, cohort studies are still needed to track growth trajectory of low BW children. Second, the information, including height and weight, was collected by questionnaires because of the large sample size, and there was underlying bias of self-reported data. Also, misunderstandings of the questions on neonatal outcome is another underlying risk. In addition, the BW records might have been wrongly recalled by the parents or guardians, thus the degree and direction of potential bias in the results were unknown. Our results suggest a need for carefully designed longitudinal studies with precise physical examination and indicators to document thinness and obesity among children with low BW.

Conclusions

In summary, low BW was positively associated with an increased risk of thinness and severe obesity but not associated with obesity. We call for special attention for children with abnormal BW for healthier physical development during growth, and their mothers by creating a favourable environment with recommendation on physical activity and nutrition and limitation of their alcohol and tobacco consumption to lower the risk of low BW. We hope the pattern of thinness and obesity in different BW groups may provide valuable insights to direct healthcare policies for improving outcomes and quality in later life.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ZJ, YY, FJ, HH and XJ helped perform the study. XJ and SL designed the research; CC drafted the manuscript and performed statistical analyses; SL and HH contributed to the interpretation of results and critically reviewed the manuscript; SL had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and declared no conflict of interest. We are grateful to all parents and teachers of the children for their assistance and cooperation in this study.

Funding: The present study was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning: Shanghai Municipal Enhancing Public Health 3-year Program (2011–2013) (11PH1951202), the National Science Foundation of China (81872637, 81728017 and 81602868), Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (201840324 and 20164Y0095), the Project of Shanghai Collaborative Innovation Center for Translational Medicine (TM201720), Program of National Science and Technology Commission for the Association of Diabetes and Nutrition in Adolescents (2016YFC1305203), the Medical and Engineering Cooperation Project of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (YG2017ZD15), the Project of Shanghai Children’s Health Service Capacity Construction (GDEK201708), the National Human Genetic Resources Sharing Service Platform (2005DKA21300), Science and Technology Development Program of Pudong Shanghai New District (PKJ2017-Y01), Shanghai Science and Technology Commission ofShanghai Municipality (17411965300, 17XD1402800) and Shanghai Professional and Technical Services Platform (18DZ2294100).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted according to the guidelines in the World Medical Association (2000) Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/) and the Guidelines for the Ethical Conduct of Medical Research Involving Children, revised in 2000 by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health: Ethics Advisory Committee (Arch Dis Child 2000, 82, 177–182). All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the institutional review boards of the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants, witnessed and formally recorded. Parents were given notification and information about the survey at the beginning of the questionnaire; it is difficult to get written consent in this large-scale population-based cross-sectional study in China.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Facts and figures on World Health Organization (WHO) childhood obesity. 2017. https://www.who.int/end-childhood-obesity/facts/en/.

- 2. Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, Narayan KM. Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. N Engl J Med 2014;370:403–11. 10.1056/NEJMoa1309753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fallucca S, Vasta M, Sciullo E, et al. Birth weight: genetic and intrauterine environment in normal pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2009;32:e149 10.2337/dc09-1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mohammad K, Kassab M, Gamble J, et al. Factors associated with birth weight inequalities in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev 2014;61:435–40. 10.1111/inr.12120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Labayen I, Moreno LA, Ruiz JR, et al. Small birth weight and later body composition and fat distribution in adolescents: the Avena study. Obesity 2008;16:1680–6. 10.1038/oby.2008.258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu ZB, Han SP, Zhu GZ, et al. Birth weight and subsequent risk of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2011;12:525–42. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ye R, Pei L, Ren A, et al. Birth weight, maternal body mass index, and early childhood growth: a prospective birth cohort study in China. J Epidemiol 2010;20:421–8. 10.2188/jea.JE20090187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:1019–26. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kapral N, Miller SE, Scharf RJ, et al. Associations between birthweight and overweight and obesity in school-age children. Pediatr Obes 2018;13 333- 41. 10.1111/ijpo.12227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Newby PK, Dickman PW, Adami HO, et al. Early anthropometric measures and reproductive factors as predictors of body mass index and obesity among older women. Int J Obes 2005;29:1084–92. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tian JY, Cheng Q, Song XM, et al. Birth weight and risk of type 2 diabetes, abdominal obesity and hypertension among Chinese adults. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;155:601–7. 10.1530/eje.1.02265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gomes FM, Subramanian SV, Escobar AM, et al. No association between low birth weight and cardiovascular risk factors in early adulthood: evidence from São Paulo, Brazil. PLoS One 2013;8:e66554 10.1371/journal.pone.0066554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lindberg J, Norman M, Westrup B, et al. Overweight, Obesity, and Body Composition in 3.5- and 7-Year-Old Swedish Children Born with Marginally Low Birth Weight. J Pediatr 2015;167:1246–52. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.08.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen C, Jin Z, Yang Y, et al. Prevalence of grade 1, 2 and 3 thinness is associated with lower socio-economic status in children in Shanghai, China. Public Health Nutr 2016;19:2002–10. 10.1017/S1368980016000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jin Z, Yang Y, Liu S, et al. Prevalence of DSM-5 Autism Spectrum Disorder Among School-Based Children Aged 3-12 Years in Shanghai, China. J Autism Dev Disord 2018;48:2434–43. 10.1007/s10803-018-3507-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes 2012;7:284–94. 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Qiao Y, Ma J, Wang Y, et al. Birth weight and childhood obesity: a 12-country study. Int J Obes Suppl 2015;5(Suppl 2):S74–9. 10.1038/ijosup.2015.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tao Y. Middle income and middie income group in Shanghai. J Soc Sci 2006;9:91–100. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schellong K, Schulz S, Harder T, et al. Birth weight and long-term overweight risk: systematic review and a meta-analysis including 643,902 persons from 66 studies and 26 countries globally. PLoS One 2012;7:e47776 10.1371/journal.pone.0047776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang X, Liu E, Tian Z, et al. High birth weight and overweight or obesity among Chinese children 3-6 years old. Prev Med 2009;49(2-3):172–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li N, Liu E, Sun S, et al. Birth weight and overweight or obesity risk in children under 3 years in China. Am J Hum Biol 2014;26:331–6. 10.1002/ajhb.22506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loaiza S, Coustasse A, Urrutia-Rojas X, et al. Birth weight and obesity risk at first grade in a cohort of Chilean children. Nutr Hosp 2011;26:214–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dubois L, Girard M. Early determinants of overweight at 4.5 years in a population-based longitudinal study. Int J Obes 2006;30:610–7. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pei L, Kang Y, Zhao Y, et al. Changes in socioeconomic inequality of low birth weight and macrosomia in Shaanxi Province of Northwest China, 2010-2013: a cross-sectional study. Medicine 2016;95:e2471 10.1097/MD.0000000000002471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou J, Zeng L, Dang S, et al. Maternal prenatal nutrition and birth outcomes on malnutrition among 7- to 10-year-old children: a 10-year follow-up. J Pediatr 2016;178:40–6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang G, Johnson S, Gong Y, et al. Weight gain in infancy and overweight or obesity in childhood across the gestational spectrum: a prospective birth cohort study. Sci Rep 2016;6:29867 10.1038/srep29867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eriksson JG. Early growth and adult health outcomes--lessons learned from the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Matern Child Nutr 2005;1:149–54. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2005.00017.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Yao L, et al. Low birth weight is associated with higher blood pressure variability from childhood to young adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176(Suppl 7):S99–105. 10.1093/aje/kws298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abitbol CL, Moxey-Mims M. Chronic kidney disease: low birth weight and the global burden of kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2016;12:199–200. 10.1038/nrneph.2016.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hanson MA, Gluckman PD. Early developmental conditioning of later health and disease: physiology or pathophysiology? Physiol Rev 2014;94:1027–76. 10.1152/physrev.00029.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.