Abstract

Objectives

As Canada’s second largest province, the geography of Quebec poses unique challenges for trauma management. Our primary objective was to compare mortality rates between trauma patients treated at rural emergency departments (EDs) and urban trauma centres in Quebec. As a secondary objective, we compared the availability of trauma care resources and services between these two settings.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

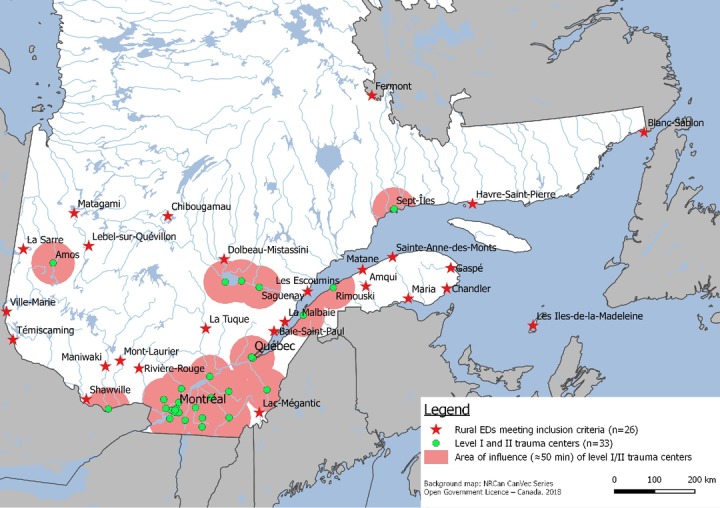

26 rural EDs and 33 level 1 and 2 urban trauma centres in Quebec, Canada.

Participants

79 957 trauma cases collected from Quebec’s trauma registry.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Our primary outcome measure was mortality (prehospital, ED, in-hospital). Secondary outcome measures were the availability of trauma-related services and staff specialties at rural and urban facilities. Multivariable generalised linear mixed models were used to determine the relationship between the primary facility and mortality.

Results

Overall, 7215 (9.0%) trauma patients were treated in a rural ED and 72 742 (91.0%) received treatment at an urban centre. Mortality rates were higher in rural EDs compared with urban trauma centres (13.3% vs 7.9%, p<0.001). After controlling for available potential confounders, the odds of prehospital or ED mortality were over three times greater for patients treated in a rural ED (OR 3.44, 95% CI 1.88 to 6.28). Trauma care setting (rural vs urban) was not associated with in-hospital mortality. Nearly all of the specialised services evaluated were more present at urban trauma centres.

Conclusions

Trauma patients treated in rural EDs had a higher mortality rate and were more likely to die prehospital or in the ED compared with patients treated at an urban trauma centre. Our results were limited by a lack of accurate prehospital times in the trauma registry.

Keywords: organisation of health services, trauma management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to specifically compare trauma mortality and the availability of trauma-related resources at rural hospitals and urban trauma centres in Canada.

This is a large retrospective cohort study of 79 957 trauma cases collected from Quebec’s trauma registry over a 4-year study period.

Our analyses included characteristics of trauma patients, their injuries and the trauma care system to determine the independent association of these factors with mortality.

Total prehospital times (not available in the current trauma registry), trauma cases initially treated in remote outposts and long-term functional outcomes were not specifically analysed in this study.

Our findings may not be generalisable to other jurisdictions due to differences in population, geography, resources, emergency medical services systems and the organisational structure of trauma care.

Introduction

Trauma is the leading cause of death for Canadians under the age of 40 and the fifth leading cause of death for Canadians of all ages.1 Although trauma care has improved dramatically since the implementation of organised trauma systems,2–5 evidence suggests there are considerable differences in mortality between patients receiving care in rural and urban settings.6–10 These differences may be attributable to longer transport times and limited availability of resources and services at rural hospitals.11 Furthermore, prehospital mortality accounts for a large proportion of rural trauma deaths.12

Approximately 20% of Canadians live in rural areas.13 Rural traumas commonly occur in the workplace (eg, industry, mining, farming), during recreational activities (ie, ‘higher-risk’ outdoor sports) and on the roadways (eg, poor driving conditions, impaired driving).6 14 These patients generally receive treatment at rural emergency departments (EDs), which often have limited access to consultation services and advanced imaging. In addition, 44% and 54% of rural EDs are located greater than 300 km from a level 1 or level 2 trauma centre, respectively, thus far exceeding the ‘golden hour’ of trauma care.15–18 Moreover, access to advanced paramedic care and air medevac capabilities is limited and varies from one provincial jurisdiction to another.19 20

As Canada’s second largest province, Quebec faces geographical challenges in providing optimal trauma care to the population. We hypothesised that rural trauma victims in Quebec have worse outcomes compared with urban trauma patients, even in a modern trauma system. The primary objective of this study was to examine mortality rates in trauma patients seen in rural EDs and urban trauma centres across the province. As a secondary objective, we compared the availability of trauma care resources and services at rural EDs and urban trauma centres in Quebec.

Methods

Setting

Quebec is Canada’s second most populous province with eight million inhabitants in 2016.21 The trauma system in Quebec was launched in 1993 and involves regionalised care from rural community hospitals through to urban level 1 trauma centres. This system relies on standardised Emergency Medical Services (EMS) resources and care providers that have the same qualifications and use the same protocols across the province. During the period this study was conducted (2009–2013), transport triage criteria were based on a combination and adaptation of the prehospital index (PHI) and high-velocity impact (HVI).22 23 A PHI score ≥4 or the presence of any significant HVI mechanism resulted in direct transport to a trauma centre (level 1 or 2) if it was within 45 min of transport time from injury location. The EMS providers also followed the PHI ‘noncumulative 5’ rule, which assumes that casualties scoring a 5 (ie, lack of vital signs) for any element of the PHI must be transported to the nearest centre (regardless of trauma designation) for initial stabilisation.

Study design and data sources

We performed a retrospective cohort study of all trauma cases in Quebec between 2009 and 2013. The protocol for this study has been previously published.24 Data were collected from the Quebec Trauma Registry Information System (BDM-SIRTQ), a population-based registry under the Ministry of Health and Social Services. The BDM-SIRTQ contains information on victims of unintentional traumatic injuries, victims who died on arrival at the ED or during ED stay, and victims who were hospitalised in a trauma centre in Quebec. This study was performed in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for reporting observational studies.25

Study definitions and inclusion criteria

For the purposes of this study, all institutions designated by the Health Authority of Quebec as level 1 or level 2 trauma centres were considered urban centres.26 Rural EDs were defined according to the following four criteria: (1) located in cities with a population of less than 15 000 (2016 census data); (2) 24/7 physician coverage; (3) hospital with patient admission capability; and (4) located more than 50 min (‘golden hour’ limit with a 10 min margin) of ground transport from a level 1 or 2 trauma centre. Ground transport times were estimated using Google Maps.27

All trauma cases occurring in Quebec during the study period and involving transport directly to a rural ED or an urban trauma centre were eligible. Deaths at the scene are not included in Quebec’s trauma registry. Regarding patient transfers, only trauma cases transferred from a rural ED to an urban trauma centre were included.

Data collection

Data were collected on patient demographics (age, sex), injury characteristics (Injury Severity Score (ISS), mechanism, type, scene of injury), mode of transport (road ambulance vs other types (eg, air, personal vehicle)), transfer to an urban trauma centre, hospital admission and patient mortality (prehospital, ED or in-hospital). Data on access to 24/7 in-hospital services were obtained directly from hospitals in the context of a previous study,28 and were updated by phone calls to participating centres in March 2017. These services included access to intensive care units (ICUs), laboratories, X-ray, CT scan, MRI and ultrasound. We also collected data on the presence of specialties commonly involved in trauma care (ie, general and orthopaedic surgery, internal medicine, neurology, anaesthesiology).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the characteristics of trauma cases, as well as the types of services and specialties available at rural hospitals and urban centres. Means and SDs are presented for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Variables with missing values are reported as such in the tables. We used Student’s t-tests and Χ2 analysis or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, to test for differences in characteristics between patients admitted to rural EDs and those transported directly to an urban trauma centre. To determine the relationship between the primary facility (rural ED vs urban trauma centre) and mortality, bivariate and multivariable generalised linear mixed models were performed and adjusted for the following variables: age, sex, ISS, injury mechanism, penetrating injury, scene of injury, craniocerebral trauma, ambulance transport and transfer. Mortality was considered during the prehospital setting (dead on arrival to initial ED), the ED setting (death during ED stay or during transfer from one ED to another) and the in-hospital setting (death after ED discharge to any destination (eg, hospital department, rehabilitation)). Intraclass coefficient correlations were calculated to assess the percentage of variance in the model explained by the primary facility. A sensitivity analysis was performed for the subgroup of severe trauma cases (ISS ≥15). The same generalised linear mixed model was used to explore the yearly variation in rural versus urban mortality by adding an interaction term between primary facility and year. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were directly involved in the development of the research question, design or measures. However, a second phase of this study will employ the Delphi method to examine potential solutions for improving trauma care in Quebec; this will include participation by representatives of trauma patients. The results of both the current investigation and the second phase of this study will be disseminated to rural patients, hospitals and to the Ministry of Health and Social Services.

Results

Fifty-nine hospitals met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis; 26 were rural EDs and 33 were urban trauma centres (figure 1). Of the 26 rural EDs, 18 were primary trauma centres (level 3), 6 were stabilisation centres (level 4), and 2 were not designated trauma centres by the Ministry of Health and Social Services.24

Figure 1.

Map of rural emergency departments (EDs) and level 1 and 2 trauma centres included in the study.

Hospital services and staff specialists

On average, rural EDs received 490 000 patient visits per year over the course of the study. Table 1 profiles the services and staff specialists in rural EDs and urban trauma centres in Quebec. Of the 26 rural EDs, 58% (15/26) were more than 150 km from an urban trauma centre. Services available at most rural hospitals included laboratory (100%, 26/26), basic X-ray (92%, 24/26), ICUs (77%, 20/26), bedside ultrasound (73%, 19/26) and CT scanners (69%, 18/26). Few rural EDs had ultrasound services for diagnostic imaging (31%, 8/26), and none had MRI services. While the majority of rural EDs had general surgeons (73%, 19/26) and anaesthesiologists (65%, 17/26) on staff, fewer than half had an internal medicine specialist (38%, 10/26), only 12% (3/26) had an orthopaedic surgeon, and none had a staff neurosurgeon. In comparison, all of the services and staff specialists examined were available at every urban trauma centre.

Table 1.

Characteristics of rural hospitals and urban trauma centres in Quebec, 2009–2013

| Characteristics | Rural EDs n=26 |

Urban TCs n=33 |

P value |

| Distance from level 1 or 2 trauma centre, n (%) | |||

| ≤150 km | 11 (42) | – | – |

| 150–300 km | 9 (35) | – | – |

| >300 km or no road | 6 (23) | – | – |

| Types of services offered 24/7, n (%) | |||

| Laboratory | 26 (100) | 33 (100) | 1.00 |

| X-ray | 24 (92) | 33 (100) | 0.19 |

| Intensive care unit | 20 (77) | 33 (100) | 0.005 |

| Portable ultrasound device (bedside ED) | 19 (73) | 33 (100) | 0.002 |

| CT scan | 18 (69) | 33 (100) | <0.001 |

| Ultrasound (radiology)* | 8 (31) | 33 (100) | 0.001 |

| MRI | 0 (0) | 33 (100) | 0.001 |

| Types of specialists, n (%) | |||

| General surgeon | 19 (73) | 33 (100) | 0.002 |

| Anaesthesiologist | 17 (65) | 33 (100) | 0.002 |

| Internal medicine specialist | 10 (38) | 33 (100) | 0.001 |

| Orthopaedic surgeon | 3 (12) | 33 (100) | 0.001 |

| Neurologist | 0 (0) | 33 (100) | 0.001 |

*Available on weekdays.

ED, emergency department; TC, trauma centre.

Profile of trauma cases

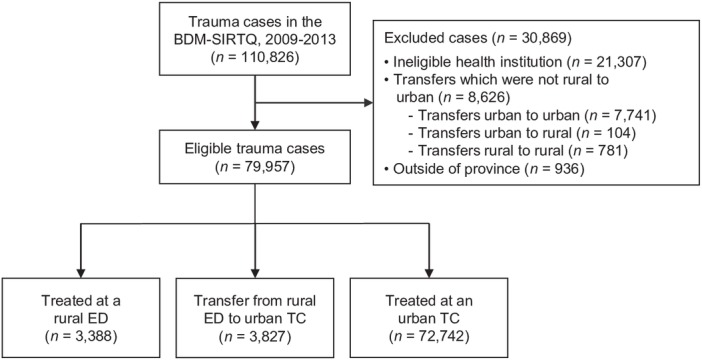

The 5-year cohort included 110 826 trauma cases in Quebec (figure 2). Of these, a total of 30 869 cases were excluded from the analysis: 936 cases pertained to traumatic events occurring outside the province, 21 307 cases were treated at ineligible hospitals, and 8626 cases involved patients who were transferred but not from a rural ED to an urban centre. The remaining 79 957 trauma cases were included, of which 72 742 (91.0%) were treated directly at level 1 or level 2 trauma centres and 7215 (9.0%) were treated at rural EDs. Among patients taken to a rural ED, 3827 (53%) were subsequently transferred to an urban centre.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of trauma cases seen in rural EDs and urban TCs in Quebec between 2009 and 2013. BDM-SIRTQ, Quebec Trauma Registry Information System; ED, emergency department; TC, trauma centre.

Table 2 compares the characteristics of trauma cases at rural EDs and urban centres. Patients who received care at rural EDs were older than patients treated at urban trauma centres (mean age 63.3±24.6 years vs 59.1±26.3 years, p<0.001). They were also older than patients who were transferred from rural EDs to urban centres (mean age 63.3±24.6 years vs 50.0±24.4 years, p<0.001). Patients transferred from a rural facility to an urban trauma centre were more likely to be male than those who were treated at rural hospitals (61% vs 48%, p<0.001). Overall, injury severity was similar between patients seen in rural EDs (median ISS 9 (IQR 4–9)) and urban trauma centres (median ISS 9 (IQR 4–9)). Most trauma cases were of low severity (88.4% of patients had an ISS <15). A greater proportion of patients with ISS >25 were treated at urban centres. Falls were the most common mechanism of injury in both settings. Urban trauma centres saw a greater proportion of fall-related traumas (69% vs 66%, p<0.001) and a smaller proportion of traumas from motor vehicle collisions (15% vs 19%, p<0.001). Injuries occurred most frequently to the limbs, followed by the head and thorax. Injury types were similar between patients treated at rural EDs and urban trauma centres.

Table 2.

Characteristics of trauma cases at rural hospitals and urban TCs

| Characteristics | Rural EDs n=3388 |

Transfers* n=3827 |

P value† | Urban TCs n=72 742 |

P value‡ |

| Demographics§ | |||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.3 (24.6) | 50.0 (24.4) | <0.001 | 59.1 (26.3) | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 1624 (48) | 2322 (61) | <0.001 | 35 031 (48) | 0.80 |

| ISS, n (%) | |||||

| 1–9 | 2823 (83) | 2907 (76) | <0.001 | 56 815 (78) | <0.001 |

| 10–15 | 229 (7) | 281 (7) | 0.335 | 7635 (11) | <0.001 |

| 16–24 | 227 (7) | 312 (8) | 0.019 | 4659 (6) | 0.496 |

| ≥25 | 109 (3) | 327 (9) | <0.001 | 3633 (5) | <0.001 |

| Injury mechanism, n (%) | |||||

| Fall | 2252 (66) | 2113 (55) | <0.001 | 50 462 (69) | <0.001 |

| MVC | 628 (19) | 971 (25) | <0.001 | 10 812 (15) | <0.001 |

| Other | 508 (15) | 743 (20) | <0.001 | 11 468 (16) | 0.23 |

| Scene of injury, n (%) | |||||

| Home | 1616 (47) | 645 (17) | <0.001 | 22 550 (31) | <0.001 |

| Street/Road | 497 (15) | 624 (16) | 0.06 | 11 908 (16) | 0.009 |

| Other | 1275 (38) | 2558 (67) | <0.001 | 38 284 (53) | <0.001 |

| Injury type¶, n (%) | |||||

| Head | 643 (19) | 661 (17) | 12 188 (17) | ||

| Face | 321 (9) | 534 (14) | 9187 (13) | ||

| Neck | 37 (1) | 40 (1) | 977 (1) | ||

| Thorax | 709 (21) | 430 (11) | 10 586 (15) | ||

| Abdominal | 195 (6) | 198 (5) | 4260 (6) | ||

| Spinal | 521 (15) | 449 (12) | 7906 (11) | ||

| Upper limb | 784 (23) | 1182 (31) | 21 659 (30) | ||

| Lower limb | 1355 (40) | 2069 (54) | 40 032 (55) | ||

| Presence of craniocerebral trauma | 345 (10) | 437 (11) | 7977 (11) | ||

| Undetermined | 176 (5) | 104 (3) | 2146 (3) | ||

| Transport, n (%) | |||||

| Ambulance | 2524 (74) | 1749 (46) | <0.001 | 54 745 (75) | 0.32 |

| Air | 1 (<1) | 5 (<1) | 0.2237 | 61 (<1) | 0.984 |

| Other | 424 (13) | 252 (6) | <0.001 | 2757 (4) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 439 (13) | 1821 (48) | <0.001 | 15 179 (21) | <0.001 |

*Patients transferred from rural EDs to urban TCs.

†Significance for difference in characteristics between trauma patients admitted to rural EDs and trauma patients transferred from rural EDs to urban centres.

‡Significance for difference in characteristics between trauma patients admitted to rural EDs and trauma patients transported directly to urban centres.

§Data were unavailable for 258 patients.

¶Some patients had >1 injury type.

ED, emergency department; ISS, Injury Severity Score; MVC, motor vehicle collision; TC, trauma centre.

Trauma mortality

Overall mortality for patients seen in rural hospitals (ie, not transferred) was 13.3% vs 7.9% for patients treated in urban level 1 and level 2 trauma centres (p<0.001). Compared with either of these groups, patients who were initially assessed and stabilised in rural EDs and subsequently transferred to an urban centre for definitive care had significantly lower overall mortality (3.1%, p<0.001). There were 113 patients (3%) that died during the transfer interval. Table 3 shows crude and adjusted ORs for the association between mortality (prehospital or ED, in-hospital) and various patient-level and institution-level factors. The odds of death prehospital or in the ED were over three times greater for trauma patients treated in a rural ED (OR 3.37, 95% CI 1.85 to 6.13). Trauma care setting (rural vs urban) was not associated with in-hospital mortality. Similar results were obtained following a sensitivity analysis limited to severe trauma cases (ISS ≥15) (online supplementary table 1).

Table 3.

Regression analysis of the relationship between rural ED admission and trauma mortality

| Variable | Prehospital or ED mortality | In-hospital mortality | ||

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | |

| Admitting facility (ref: urban trauma centre) | ||||

| Rural ED | 0.98 (0.63 to 1.54) | 3.37 (1.85 to 6.13) | 0.77 (0.58 to 1.01) | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.14) |

| Age (ref: ≥65) | ||||

| 0–15 years | 0.97 (0.74 to 1.26) | 0.73 (0.55 to 0.98) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.04) | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.07) |

| 16–64 years | 5.46 (4.95 to 6.03) | 1.99 (1.76 to 2.25) | 0.16 (0.14 to 0.17) | 0.16 (0.15 to 0.18) |

| Male | 3.65 (3.33 to 4.00) | 1.91 (1.72 to 2.12) | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.96) | 1.33 (1.23 to 1.43) |

| ISS (ref: ≥25) | ||||

| 1–9 | 0.14 (0.13 to 0.16) | 0.34 (0.29 to 0.39) | 0.12 (0.11 to 0.13) | 0.10 (0.09 to 0.11) |

| 10–15 | 0.11 (0.09 to 0.13) | 0.16 (0.13 to 0.19) | 0.16 (0.14 to 0.18) | 0.13 (0.11 to 0.15) |

| 16–24 | 0.24 (0.20 to 0.28) | 0.28 (0.23 to 0.34) | 0.26 (0.23 to 0.30) | 0.23 (0.20 to 0.27) |

| Injury mechanism (ref: other) | ||||

| Fall | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.04) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) | 2.81 (2.45 to 3.22) | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.36) |

| MVC | 0.63 (0.57 to 0.69) | 0.49 (0.42 to 0.59) | 1.22 (1.02 to 1.45) | 0.86 (0.69 to 1.09) |

| Penetrating injury (ref: none) | ||||

| Lower/Upper limbs | 1.09 (0.74 to 1.60) | 0.34 (0.23 to 0.52) | 0.21 (0.10 to 0.42) | 0.67 (0.33 to 1.37) |

| Thorax/abdomen/back | 11.24 (9.71 to –13.00) | 1.89 (1.58 to 2.26) | 0.76 (0.56 to 1.04) | 1.35 (0.95 to 1.92) |

| Scene of injury (ref: other) | ||||

| Road/Street | 5.10 (4.60 to 5.66) | 1.87 (1.59 to 2.21) | 0.68 (0.60 to 0.77) | 0.66 (0.55 to 0.78) |

| Domicile | 2.86 (2.59 to 3.16) | 4.03 (3.58 to 4.54) | 1.82 (1.70 to 1.96) | 1.16 (1.07 to 1.25) |

| Craniocerebral trauma | 2.06 (1.86 to 2.29) | 1.65 (1.45 to 1.88) | 2.53 (2.32 to 2.76) | 1.16 (1.03 to 1.30) |

| Ambulance transport | 14.04 (10.94 to –18.03) | 14.69 (11.30 to –19.09) | 7.15 (6.14 to 8.32) | 4.21 (3.60 to 4.93) |

| Transfer | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.04) | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.02) | 0.61 (0.48 to 0.78) | 0.98 (0.74 to 1.29) |

Intraclass coefficient: 0.15 for prehospital or ED mortality, 0.06 for in-hospital mortality.

*Adjusted for age, sex, ISS, injury mechanism, scene of injury, penetrating injury, craniocerebral trauma, ambulance transport and transfer.

ED, emergency department; ISS, Injury Severity Score; MVC, motor vehicle collision; ref, reference.

bmjopen-2018-028512supp001.pdf (26.6KB, pdf)

We compared adjusted mortality rate fluctuations between 2009 and 2013 for participating centres (online ssupplementary figure 1). Mortality in rural EDs over the 5-year study period decreased by 3.74% vs 2.34% for urban trauma centres, but this difference was not significant (p=0.18). Despite decreased trauma mortality at both urban and rural hospitals, the gap in mortality between these two settings remained constant.

bmjopen-2018-028512supp002.pdf (41.9KB, pdf)

Discussion

This is the first study to describe and compare trauma cases presenting to rural EDs and urban centres in the province of Quebec. We found that overall mortality was greater for trauma patients seen in rural EDs (13.3% vs 7.9%). After adjusting for potential available confounders, the odds of prehospital or ED mortality were more than three times greater for trauma patients treated in rural EDs compared with urban trauma centres. Although mortality rates decreased at both rural and urban centres over the 5-year study period, the mortality gap between these settings remained constant. Roughly half of rural ED cases that survived the initial stabilisation phase were transferred to an urban trauma centre; these patients had significantly lower mortality rates than non-transferred patients despite having greater injury severity. Compared with rural EDs, a larger proportion of urban centres offered all services (with the exception of laboratory and X-ray) and employed all types of staff specialists evaluated. Taken together, our findings demonstrate important differences in available care and outcomes for trauma patients in Quebec.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this was an analysis of data collected from a provincial trauma registry and thus subject to the inherent confines of retrospective studies. Data for some of the variables assessed were incomplete. Furthermore, the trauma registry does not capture the time interval from the 911 call to ambulance arrival at the scene, which precluded our ability to calculate total prehospital times; this is a significant limitation of this study as prehospital time is a critical potential confounder. Second, this study did not include trauma cases that were initially treated in remote outposts. Hence, our results may have minimised trauma mortality in areas that were more resource-limited, or isolated and vulnerable. Moreover, this study was not designed to compare long-term functional outcomes following trauma; this could be the focus of future studies. Finally, although this study was conducted in Canada’s second largest province, our findings may not be generalisable to other jurisdictions due to differences in population, geography, resources, EMS systems and in the organisational structure of trauma care.

Our observation that mortality rates were higher in trauma cases at rural EDs, especially in the prehospital phase, is consistent with previous studies.6 7 29 30 Indeed, higher mortality rates in the prehospital phase of care have been reported in the literature for more than 20 years.7 31 In a population-based analysis of all trauma deaths in the province of Ontario, Gomez et al 30 found that over half of rural trauma deaths occurred in the prehospital setting. Furthermore, among trauma patients who survived long enough to reach hospital, the risk of ED mortality was three times greater for patients injured in areas with limited access to trauma centre care. In another study of trauma patients served by EMS in rural and urban counties in Oregon and Washington, Newgard et al 12 found that half of rural trauma deaths occurred prehospital, and that 90% of rural deaths took place within 24 hours of injury (compared with 64% of urban deaths). Although overall mortality rates did not differ between rural and urban regions, the authors suggested that the lack of a statistically significant difference may reflect a rural sample size that was underpowered to detect such a difference. It has been noted that the overall prehospital period in the USA is almost one-third longer in rural settings compared with urban environments.32 Several studies conducted in Quebec suggest there is an association between total prehospital time and mortality in seriously injured patients, which is consistent with the concept of the ‘golden hour’ in trauma.33 34 Although time to definitive care is a major determinant of trauma outcomes, assessing this relationship across a field-defined population of injured persons using EMS intervals has generally produced inconclusive results.12 Furthermore, testing the hypothesis that shorter EMS intervals improve outcomes requires rigorous study designs that are often impracticable.

This study is part of a larger project aimed at finding solutions to improve rural trauma and emergency care in Quebec.24 A Delphi phase to this project is currently under way, as well as a large-scale qualitative study that mobilises multiple stakeholders (citizens, decision makers, healthcare professionals) to participate in efforts to improve rural emergency care.35 Potential solutions currently being explored include improving databases to better capture EMS intervals,24 piloting the implementation of a helicopter EMS system,36 incorporating telehealth in the prehospital and rural ED settings,37 38 and deploying mobile trauma simulation training programmes in rural EDs.39 These solutions could be deployed in rural areas that are most at risk for trauma mortality.

Conclusions

The results of this study illustrate significant differences in mortality and resource availability at rural hospitals and urban trauma centres in Quebec. The likelihood of mortality was over three times higher for patients treated at rural EDs versus urban trauma centres. While mortality rates decreased at both rural and urban facilities over the study period, the gap in mortality between these settings remained constant; this is a finding of concern in a universal healthcare system. Solutions to improve trauma care in Quebec are currently being explored and deployed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Percipient Research & Consulting for assisting with language editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: RF, JPo, MO, J-PF, FLé, FLa and GD conceived the study, designed the protocol and obtained research funding. RF and CT-P performed the literature search. RF, FKT and ST supervised the data collection. RF, FLa, JPl, JM and ST provided statistical advice on study design and analysed the data. All authors contributed to interpreting the data and drafting the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final version of the submitted manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work was supported by the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ) - Consortium pour le développement de la recherche en traumatologie 2015–2018.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the CISSS Chaudière-Appalaches Research Ethics Committee (Project MP-2016-003).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Map disclaimer: The depiction ofboundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of anyopinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerningthe legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of itsauthorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, eitherexpress or implied.

References

- 1. Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0394-01 Leading causes of death, total population, by age group. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310039401 (Accessed 12 Jul 2018).

- 2. Kuimi BL, Moore L, Cissé B, et al. . Influence of access to an integrated trauma system on in-hospital mortality and length of stay. Injury 2015;46:1257–61. 10.1016/j.injury.2015.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moore L, Champion H, Tardif PA, et al. . Impact of Trauma System Structure on Injury Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Surg 2018;42:1327–39. 10.1007/s00268-017-4292-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, et al. . The national study on costs and outcomes of trauma. J Trauma 2007;67:S81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moore L, Turgeon AF, Lauzier F, et al. . Evolution of patient outcomes over 14 years in a mature, inclusive Canadian trauma system. World J Surg 2015;39:1397–405. 10.1007/s00268-015-2977-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peek-Asa C, Zwerling C, Stallones L. Acute traumatic injuries in rural populations. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1689–93. 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitchell RJ, Chong S. Comparison of injury-related hospitalised morbidity and mortality in urban and rural areas in Australia. Rural Remote Health 2010;10:1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim K, Ozegovic D, Voaklander DC. Differences in incidence of injury between rural and urban children in Canada and the USA: a systematic review. Inj Prev 2012;18:264–71. 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pampalon R, Martinez J, Hamel D. Does living in rural areas make a difference for health in Québec? Health Place 2006;12:421–35. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lagacé C, Desmeules M, Pong RW, et al. . Non-communicable disease and injury-related mortality in rural and urban places of residence: a comparison between Canada and Australia. Can J Public Health 2007;98:S62–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jarman MP, Castillo RC, Carlini AR, et al. . Rural risk: Geographic disparities in trauma mortality. Surgery 2016;160:1551–9. 10.1016/j.surg.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Newgard CD, Fu R, Bulger E, et al. . Evaluation of Rural vs Urban Trauma Patients Served by 9-1-1 Emergency Medical Services. JAMA Surg 2017;152:11–18. 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Statistics Canada. Table 17-10-0118-01 Selected population characteristics, Canada, provinces and territories. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710011801 (Accessed 5 Aug 2018).

- 14. Garcia MC, Faul M, Massetti G, et al. . Reducing Potentially Excess Deaths from the Five Leading Causes of Death in the Rural United States. MMWR Surveill Summ 2017;66:1–7. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6602a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fleet R, Audette LD, Marcoux J, et al. . Comparison of access to services in rural emergency departments in Quebec and British Columbia. CJEM 2014;16:437–48. 10.1017/S1481803500003456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fleet R, Pelletier C, Marcoux J, et al. . Differences in access to services in rural emergency departments of Quebec and Ontario. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123746 10.1371/journal.pone.0123746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fleet R, Poitras J, Maltais-Giguère J, et al. . A descriptive study of access to services in a random sample of Canadian rural emergency departments. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003876 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bergeron C, Fleet R, Tounkara FK, et al. . Lack of CT scanner in a rural emergency department increases inter-facility transfers: a pilot study. BMC Res Notes 2017;10:772 10.1186/s13104-017-3071-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nolan B, Tien H, Sawadsky B, et al. . Comparison of helicopter emergency medical services transport types and delays on patient outcomes at two level i trauma centers. Prehosp Emerg Care 2017;21:327–33. 10.1080/10903127.2016.1263371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dalton M. CBC News. Quebec’s lack of emergency air ambulance system ’embarrassing,' renowned doctor says. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-air-ambulence-david-mulder-1.4614451 (Accessed 12 Jun 2018).

- 21. Statistics Canada. Census profile, 2016 census. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (Accessed June 8 2018).

- 22. Koehler JJ, Baer LJ, Malafa SA, et al. . Prehospital Index: a scoring system for field triage of trauma victims. Ann Emerg Med 1986;15:178–82. 10.1016/S0196-0644(86)80016-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lavoie A, Bourgeois G, Lapointe J. Notice regarding field trauma criteria. ETMIS 2013;9:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fleet R, Tounkara FK, Ouimet M, et al. . Portrait of trauma care in Quebec’s rural emergency departments and identification of priority intervention needs to improve the quality of care: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010900 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux. Cadre normatif du Système d’information du Registre des traumatismes du Québec - Annexe 13 Liste des installations désignées http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-001684/?&txt=registre&msss_valpub&date=DESC&titre=ASC (Accessed 8 Jun 2018).

- 27. Wallace DJ, Kahn JM, Angus DC, et al. . Accuracy of prehospital transport time estimation. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:9–16. 10.1111/acem.12289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fleet R, Poitras J, Archambault P, et al. . Portrait of rural emergency departments in Québec and utilization of the provincial emergency department management Guide: cross sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:572 10.1186/s12913-015-1242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fatovich DM, Phillips M, Langford SA, et al. . A comparison of metropolitan vs rural major trauma in Western Australia. Resuscitation 2011;82:886–90. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gomez D, Berube M, Xiong W, et al. . Identifying targets for potential interventions to reduce rural trauma deaths: a population-based analysis. J Trauma 2010;69:633–9. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b8ef81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rogers FB, Shackford SR, Hoyt DB, et al. . Trauma deaths in a mature urban vs rural trauma system. A comparison. Arch Surg 1997;132:376–82. 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430280050007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carr BG, Caplan JM, Pryor JP, et al. . A meta-analysis of prehospital care times for trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care 2006;10:198–206. 10.1080/10903120500541324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sampalis JS, Denis R, Lavoie A, et al. . Trauma care regionalization: a process-outcome evaluation. J Trauma 1999;46:565–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sampalis JS, Lavoie A, Williams JI, et al. . Impact of on-site care, prehospital time, and level of in-hospital care on survival in severely injured patients. J Trauma 1993;34:252–61. 10.1097/00005373-199302000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fleet R, Dupuis G, Fortin JP, et al. . Rural emergency care 360°: mobilising healthcare professionals, decision-makers, patients and citizens to improve rural emergency care in the province of Quebec, Canada: a qualitative study protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016039 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Touzin C. Transport de patients par hélicoptère: Québec lance un projet pilote. https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/sante/201806/21/01-5186809-transport-de-patients-par-helicoptere-quebec-lance-un-projet-pilote.php (Accessed 18 Jul 2018).

- 37. Amadi-Obi A, Gilligan P, Owens N, et al. . Telemedicine in pre-hospital care: a review of telemedicine applications in the pre-hospital environment. Int J Emerg Med 2014;7:29 10.1186/s12245-014-0029-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duchesne JC, Kyle A, Simmons J, et al. . Impact of telemedicine upon rural trauma care. J Trauma 2008;64:92–8. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815dd4c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martin D, Bekiaris B, Hansen G. Mobile emergency simulation training for rural health providers. Rural Remote Health 2017;17:4057 10.22605/RRH4057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028512supp001.pdf (26.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028512supp002.pdf (41.9KB, pdf)