Abstract

Anti‐PUF60 autoantibodies are reportedly detected in the sera of patients with dermatomyositis and Sjögren's syndrome; however, little is known regarding its existence in the sera of cancer patients. FIR, a splicing variant of the PUF60 gene, is a transcriptional repressor of c‐myc. In colorectal cancer, there is an overexpression of the dominant negative form of FIR, in which exon 2 is lacking (FIRΔexon2). Previously, large‐scale SEREX (serological identification of antigens by recombinant cDNA expression cloning) screenings have identified anti‐FIR autoantibodies in the sera of cancer patients. In the present study, we revealed the presence and significance of anti‐FIR (FIR/FIRΔexon2) Abs in the sera of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Our results were validated by an amplified luminescence proximity homogeneous assay using sera of patients with various cancer types. We revealed that anti‐FIRΔexon2 Ab had higher sensitivity than anti‐FIR Ab. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was applied for evaluating the use of anti‐FIRΔexon2 Ab as candidate markers such as anti‐p53 Ab and carcinoembryonic antigen, and the highest area under the ROC curve was observed in the combination of anti‐FIRΔexon2 Ab and anti‐p53 Ab. In summary, our results suggest the use of anti‐FIRΔexon2 Ab in combination with the anti‐p53 Ab as a predictive marker for ESCC. The area under the ROC curve was further increased in the advanced stage of ESCC. The value of anti‐FIRΔexon2 autoantibody as novel clinical indicator against ESCC and as a companion diagnostic tool is discussed.

Keywords: AlphaLISA, anti‐FIRΔexon2 autoantibody, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, gastrointestinal cancer, SEREX

Abbreviations

- AlphaLISA

amplified luminescence proximity homogeneous assay

- AUC

area under the ROC curve

- CEA

carcinoembryonic antigen

- CFAP70

cilia and flagella‐associated protein 70

- FIR

FUBP1‐interacting repressor

- FIRΔexon2

splicing variant of FIR that lacks exon 2

- FUBP1

FUSE binding protein 1

- FUSE

far upstream element

- GST

glutathione S‐transferase

- HD

healthy donor

- IPTG

isopryl‐β‐d‐thiogalactoside

- KARS

lysyl‐tRNA synthetase

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SEREX

serological identification of antigens by recombinant cDNA expression cloning

- SNX15

sorting nexin 15

- SOHLH1

spermatogenesis and oogenesis specific basic helix‐loop‐helix 1

1. INTRODUCTION

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is one of the most common and lethal gastrointestinal malignancies worldwide.1, 2 Despite multimodal treatments, such as radical surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the 5‐year survival rate of patients with ESCC remains extremely low due to its highly invasive and metastatic nature.3, 4 The pathophysiology of ESCC is not entirely understood; thus, further research into the discovery and development of effective biomarkers for ESCC diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment is warranted.

The SEREX is an effective screening method for identifying serum Ab‐type tumor markers.5 We have previously undertaken large‐scale SEREX screenings where numerous candidates for ESCC SEREX antigens were identified and potential novel diagnostic markers for digestive organ cancers were discovered.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

In the majority of colorectal cancers, c‐myc is overexpressed and required for tumor maintenance.13, 14 The FUSE is a sequence required for the proper expression of the human c‐myc gene. It is located 1.5 kb upstream of the c‐myc promoter P1 and binds FUBP1, a transcription factor that stimulates c‐myc expression in a FUSE‐dependent manner.15, 16 The FUBP1 regulates the proliferation and migration of cells and is overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma.17, 18, 19 Yeast 2‐hybrid analysis revealed that FUBP1 binds to a protein that has transcriptional inhibitory activity, termed FIR, and FIR was found to engage the TFIIH/p89/XPB helicase and repress c‐myc transcription.20

Apoptosis is induced by FIR through c‐myc suppression; thus, it is a suitable target for anticancer therapy.21, 22 FIRΔexon2, a splicing variant of FIR that lacks exon 2, failed to repress c‐myc and inhibited FIR‐induced apoptosis, suggesting that FIRΔexon2 is a dominant negative form of FIR in human cancers.23 Alternatively, FIR is a splicing variant form of the poly(U)‐binding‐splicing factor, PUF60.24, 25 Anti‐PUF60 autoantibodies are reportedly detected in the sera of patients with autoimmune diseases such as dermatomyositis, Sjögren's syndrome, and idiopathic inflammatory myopathy.26, 27 This suggests that the combination of anti‐FIR Abs with other clinically available tumor markers, such as anti‐p53 Abs, CEA, and CA19‐9, could increase the specificity and accuracy of diagnosis.28, 29, 30, 31, 32 The present study aimed to explore the presence and significance of anti‐FIRΔexon2 Abs in the sera of patients with ESCC and to determine its use as a potential candidate marker.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Clinical samples

The present study was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Sera of patients with ESCC (n = 95) were obtained from the Department of Frontier Surgery (Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan). Sera of healthy donors (HDs) (n = 94) were obtained from the Higashi Funabashi Hospital, Funabashi City, Chiba, Japan. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study. Each serum sample was centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 minutes and the supernatant was stored at −80°C until further use. Repeated thawing and freezing of the samples was avoided. This study was approved by the Local Ethical Review Board of the Chiba University, Graduate School of Medicine and the Higashi Funabashi Hospital.

2.2. Screening by expression cloning

Recombinant DNA studies were undertaken with permission from the Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine and were carried out in accordance with the rules of the Japanese government. We used a λZAP II phage cDNA library prepared from the mRNA of T.Tn cells (esophageal cancer cell line)33, 34 and a commercially available human fetal testis cDNA library (Uni‐ZAP XR Premade Library; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) to screen for clones that were immunoreactive against serum IgG from patients with ESCC as previously described.35 Escherichia coli XL1‐Blue MRF’ was infected with λZAP II or Uni‐ZAP XR phage and the expression of resident cDNA clones was induced after blotting the infected bacteria onto NitroBind nitrocellulose membranes (Osmonics, Minnetonka, MN, USA). The membranes were pretreated with 10 mmol/L IPTG (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan) for 30 minutes. The membranes with bacterial proteins were rinsed 3 times with TBST (20 mmol/L Tris‐HCl [pH 7.5], 0.15 mol/L NaCl, and 0.05% Tween‐20), and nonspecific binding was blocked by incubating with 1% protease‐free BSA (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan) in TBST for 1 hour. The membranes were exposed to 1:2000‐diluted sera of patients for 1 hour. After 3 washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated for 1 hour with 1:5000‐diluted alkaline phosphatase‐conjugated goat anti‐human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). Positive reactions were developed using 100 mmol/L Tris‐HCl (pH 9.5) containing 100 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.15 mg/mL of 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolylphosphate, and 0.3 mg/mL of nitro blue tetrazolium (Wako Pure Chemicals).

Monoclonal phage cDNA clones were converted to pBluescript phagemids by excision in vivo using the ExAssist helper phage (Stratagene). Plasmid pBluescript containing cDNA was obtained from the E. coli SOLR strain after transformation by the phagemid. The sequences of cDNA inserts were evaluated for homology with identified genes or proteins within the public sequence database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

2.3. Expression and purification of antigen proteins

The expression plasmids of GST‐fused proteins were constructed by recombining the cDNA sequences into pGEX‐4T‐3 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The inserted DNA fragments were ligated into pGEX‐4T‐3 using Ligation Convenience Kits (Nippon Gene). Ligation mixtures were used for transforming ECOS‐competent E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Nippon Gene), and appropriate recombinants were confirmed by DNA sequencing as well as protein expression analyses. Treating the transformed E. coli with 0.1 mmol/L IPTG for 3 hours induced the expression of the GST‐fusion proteins. The GST‐fused recombinant proteins were purified by glutathione sepharose column chromatography in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and dialyzed against PBS as described in previous studies.36, 37

2.4. Amplified luminescence proximity homogeneous assay

Amplified luminescence proximity homogeneous assay (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was carried out using 384‐well microtiter plates (white opaque OptiPlate; PerkinElmer) containing 2.5 μL of 1:100‐diluted sera and 2.5 μL GST or GST‐fusion proteins (10 μg/mL) in AlphaLISA buffer (25 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.1% casein, 0.5% Triton X‐100, 1 mg/mL dextran‐500, and 0.05% Proclin‐300). The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 6‐8 hours. Next, anti‐human IgG‐conjugated acceptor beads (2.5 μL of 40 μg/mL) and glutathione‐conjugated donor beads (2.5 μL of 40 μg/mL) were added and incubated further for 7‐21 days at room temperature in the dark. The chemical emission was read on an EnSpire Alpha microplate reader (PerkinElmer) as previously described.38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Selective reactions were calculated by subtracting Alpha values of GST control from the values of GST‐fusion proteins.

2.5. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were undertaken using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and R 3.5.1 statistical software (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria) . The Mann‐Whitney U test was used for determining the significance of differences between 2 groups. The predictive values of markers for disease were assessed by ROC curve analysis. Cut‐off values were determined by the values that maximize the sums of the sensitivity and specificity. All tests were 2‐tailed and a P value below 0.05 was considered significant. Antibody group‐specific Z‐scores were calculated for facilitating the comparison across all Ab groups. Z‐score analysis was carried out after normalization to healthy donor mean values:

The combined ROC analysis was undertaken by adding each Z score. To compare the significant differences among the single or combined ROCs, AUCs were calculated and examined by DeLong tests.46, 47, 48, 49 The following formula is used the DeLong test:

3. RESULTS

3.1. Identification of SEREX antigens in the sera of ESCC patients

Five SEREX antigens were identified in the sera of patients with ESCC by the expression cloning assay through λZAP II library construction, including FIRΔexon2 (Accession No. NM_001271099.1),24, 50 KARS (Accession No. NM_001130089.1),51, 52, 53 SNX15 (Accession No. NM_013306.4),54, 55 SOHLH1 (Accession No. NM_001101677.1),56, 57 and cilia and flagella‐associated protein 70 (CFAP70) (Accession No. NM_145170.3).58 Recombinant proteins were expressed in E. coli as GST‐fusion proteins and were purified by affinity‐chromatography using glutathione sepharose column (Table S1).29

3.2. Higher levels of autoantibodies were detected in the sera of ESCC patients than that of healthy donors

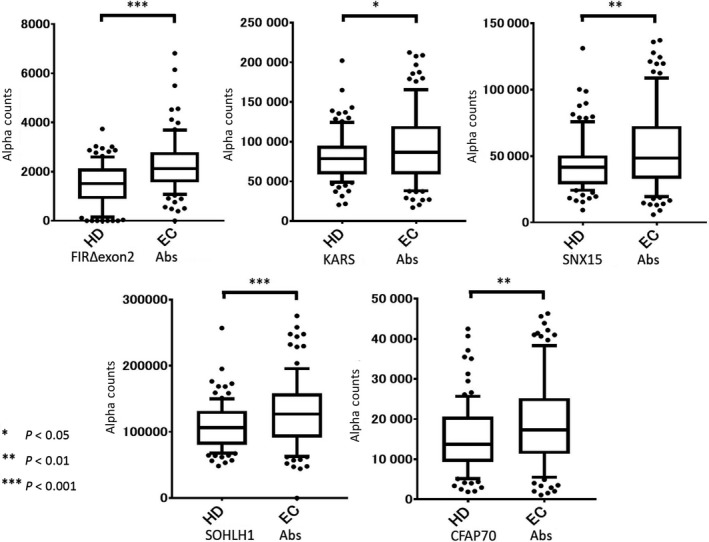

The levels of serum autoantibodies were analyzed by AlphaLISA using the sera of HDs (Table S2) and patients with ESCC obtained from Higashi Funabashi Hospital and from Chiba University Hospital, respectively. Results showed that the levels of FIRΔexon2, KARS, SNX15, SOHLH1, and CFAP70 Abs were significantly higher in patients with ESCC compared with HD (Figure 1). The cut‐off value was determined as the average + 2 SDs of HD (95% confidence interval). The percentages of Ab‐positive cases are as follows: FIRΔexon2 (17/95, 18%), KARS (14/95, 15%), SNX15 (17/95, 18%), SOHLH1 (12/95, 13%), and CFAP70 Abs (12/95, 13%) (Table 1). Clinical features of patients with ESCC are listed in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Comparison of levels of Abs against SEREX and FIRΔexon2 antigens in ESCC patients. The levels of Abs against FIRΔexon2, KARS, SNX15, SOHLH1, and CFAP70 Abs in healthy donors (HD) and patients with ESCC (EC) examined by AlphaLISA are shown. Serum Ab levels examined by AlphaLISA are shown using a box‐whisker plot. The box plots display the 10th, 20th, 50th, 80th, and 90th percentiles. P values compared with the HD specimens are shown. P values were calculated using Mann‐Whitney U test

Table 1.

Percentage of Ab‐positive cases on AlphaLISA

| FIRΔexon2 Abs | % | P value | KARS Abs | % | P value | SNX15 Abs | % | P value | SOHLH1 Abs | % | P value | CFAP70 Abs | % | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy subjects | (94) | 1 | (1) | 3 | (3) | 5 | (5) | 2 | (2) | 5 | (5) | |||||

| Esophageal cancer | (95) | 17 | (18) | <0.001 | 14 | (15) | 0.042 | 17 | (18) | 0.004 | 12 | (13) | 0.001 | 12 | (13) | 0.009 |

P values were calculated by Mann‐Whitney U test.

Comparison of auto‐Abs detected in the sera between ESCC patients and healthy subjects examined by AlphaLISA.

Table 2.

List of clinical features of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

| Esophageal cancer | FIRΔexon2 Abs (positive rate %) | P value | CFAP70 Abs (positive rate %) | P value | KARS Abs (positive rate %) | P value | SNX15 Abs (positive rate %) | P value | SOHLH1 Abs (positive rate %) | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||

| Male (84) | 15 | (18) | 11 | (13) | 14 | (17) | 16 | (19) | 12 | (14) | ||||||

| Female (11) | 2 | (18) | 0.979 | 1 | (9) | 0.707 | 0 | (0) | 0.143 | 1 | (9) | 0.418 | 0 | (0) | 0.180 | |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| ≤67 y (45) | 7 | (16) | 4 | (9) | 3 | (7) | 5 | (11) | 3 | (7) | ||||||

| >67 y (50) | 10 | (20) | 0.573 | 8 | (16) | 0.298 | 11 | (22) | 0.035 | 12 | (24) | 0.102 | 9 | (18) | 0.097 | |

| Stage | ||||||||||||||||

| 0, I, II (38) | 9 | (24) | 4 | (11) | 5 | (13) | 8 | (21) | 2 | (5) | ||||||

| III, IV (50) | 6 | (12) | 0.149 | 6 | (12) | 0.829 | 7 | (14) | 0.909 | 8 | (16) | 0.543 | 9 | (18) | 0.074 | |

| N.D. (7) | 2 | (29) | 2 | (29) | 2 | (29) | 1 | (14) | 1 | (14) | ||||||

| CEA | ||||||||||||||||

| Positive (18) | 4 | (22) | 6 | (33) | 8 | (44) | 7 | (39) | 5 | (28) | ||||||

| Negative (75) | 13 | (17) | 0.630 | 6 | (8) | 0.004 | 6 | (8) | <0.001 | 8 | (11) | 0.004 | 7 | (9) | 0.036 | |

| N.D. (2) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (50) | 0 | (0) | ||||||

| CYFRA | ||||||||||||||||

| Positive (32) | 4 | (13) | 6 | (19) | 5 | (16) | 7 | (22) | 7 | (22) | ||||||

| Negative (60) | 13 | (22) | 0.281 | 5 | (8) | 0.143 | 9 | (13) | 0.937 | 10 | (12) | 0.540 | 5 | (7) | 0.066 | |

| N.D. (3) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (33) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||

| p53‐Abs | ||||||||||||||||

| Positive (29) | 9 | (31) | 5 | (17) | 7 | (24) | 7 | (24) | 6 | (21) | ||||||

| Negative (64) | 8 | (13) | 0.032 | 6 | (9) | 0.277 | 7 | (11) | 0.099 | 10 | (16) | 0.325 | 6 | (9) | 0.132 | |

| N.D. (2) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (50) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||

| eso‐SCC | ||||||||||||||||

| Positive (36) | 8 | (22) | 6 | (17) | 10 | (28) | 9 | (25) | 10 | (28) | ||||||

| Negative (56) | 9 | (16) | 0.458 | 5 | (9) | 0.264 | 4 | (7) | 0.007 | 7 | (13) | 0.123 | 2 | (4) | <0.001 | |

| N.D. (3) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (33) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (33) | 0 | (0) | ||||||

P‐values were calculated by Pearson's χ2 test.N.D., not determined.

3.3. Anti‐FIRΔexon2 Ab is an independent marker of ESCC

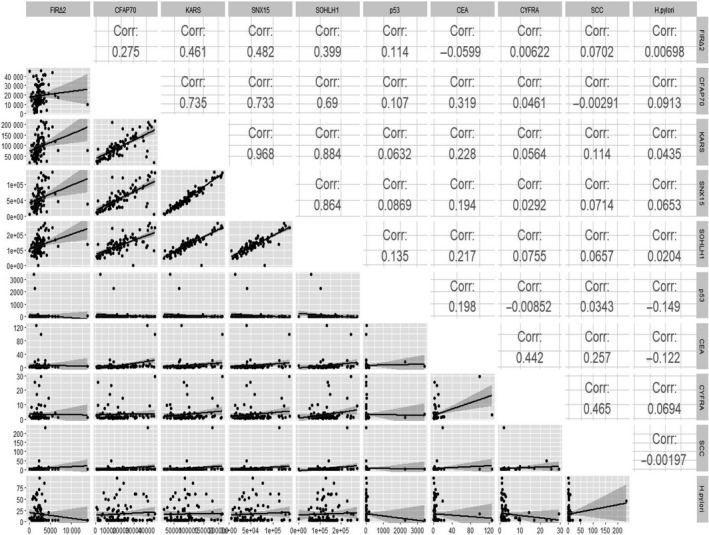

Spearman's rank correlation analysis was used for exploring whether a correlation exists between FIRΔexon2, KARS, SNX15, SOHLH1, or CFAP70 Abs and clinically used tumor markers. As indicated in Figure 2, the correlation coefficient between FIRΔexon2 Abs and clinically used tumor markers was not significant. KARS Abs were positively correlated with SNX15, SOHLH1, and CFAP70 Abs, but not with FIRΔexon2 Abs (Figure 2). Next, clinical features of patients with ESCC were explored.

Figure 2.

Correlation coefficients between candidate markers and clinically used tumor markers for detection of ESCC patients. The correlation (Corr) between the groups was assessed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. The lower triangular matrix shows the pairwise scatter plots between variables, whereas the upper triangular matrix shows Spearman's rank correlation coefficients among each paired measurement

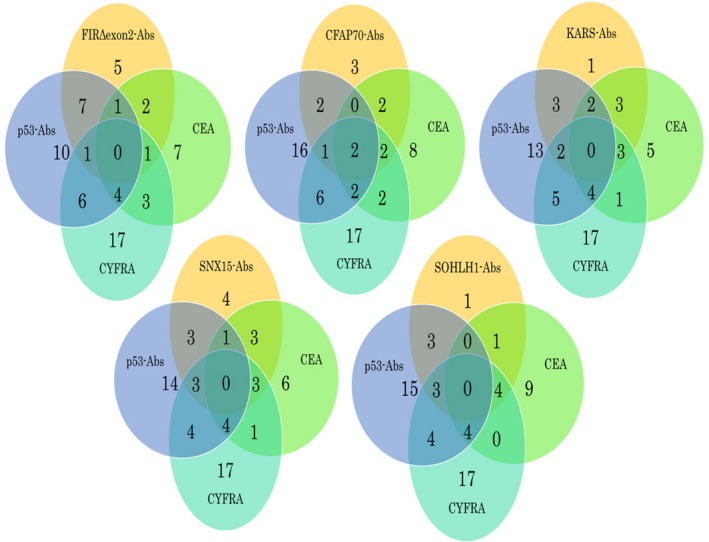

Venn diagram analysis showed that Ab‐positive cases, including 5 cases of FIRΔexon2, 3 cases of CFAP70, 1 case of KARS, 4 cases of SNX15, and 1 case of SOHLH1 Abs, were noncommon Ab‐positive cases between the p53 Abs, CEA, and CYFRA comparison groups. In addition, 4 candidate markers, including FIRΔexon2, KARS, SNX15, and SOHLH1 Abs, were not common Ab‐positive cases between the p53 Abs, CEA, and CYFRA comparison groups (Figure 3). These results indicate that FIRΔexon2 Abs have no relation with clinically used tumor markers over other candidate markers. In addition, there was no correlation between anti‐FIRΔexon2 Abs and the 9 tumor markers analyzed, thereby suggesting that anti‐FIRΔexon2 Abs are independent markers of ESCC.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram analysis among candidate markers and clinically used tumor markers. Results of Venn diagram analysis for differentially detected markers identified from patients of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

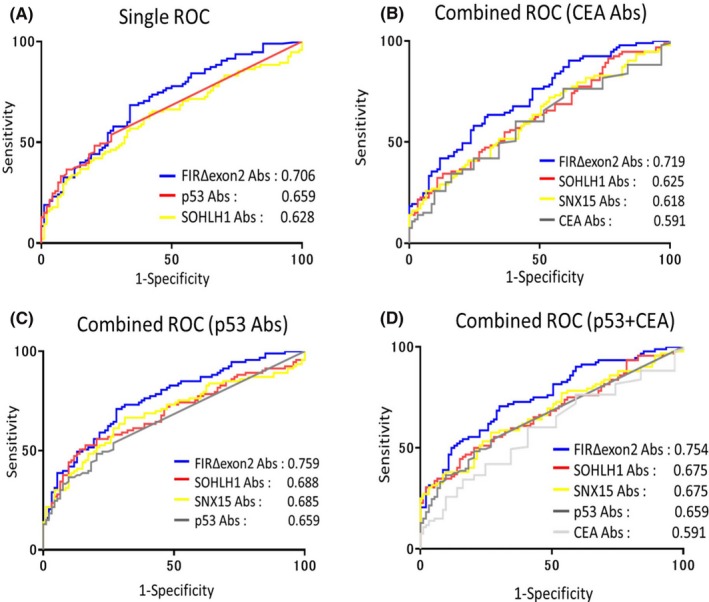

3.4. Values of AUCs were increased in the combined ROC analysis compared to the individual ROC analysis

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was carried out for evaluating the ability of these candidate markers for detecting ESCC. The highest AUC values were obtained for FIRΔexon2 Abs compared to other ESCC candidate markers (Figure 4A). The Ab group‐specific Z‐scores were calculated to facilitate the comparison across all Ab groups. Among the Abs combined with CEA, only the AUC of SOHLH1 decreased to 0.6245 in sera of patients with ESCC. However, the AUC of the remaining Abs increased. Furthermore, the AUC of FIRΔexon2 Abs increased to 0.7190 in the sera of patients with ESCC (Figure 4B). Among all the Abs combined with p53 Abs, FIRΔexon2 showed an AUC of 0.759 in ESCC. There were no Abs with an AUC larger than 0.750, however, the AUC values were increased in the combined ROC analysis compared with the individual ROC analysis for all Abs (Figure 4C). Among the Abs combined with the both p53 and CEA Abs, FIRΔexon2 Abs showed an AUC of greater than 0.750 in the sera of patients with ESCC. There were no Abs with an AUC larger than 0.750, however, the AUC values were increased in the combined ROC analysis compared to the individual ROC analysis (Figure 4D). The highest AUC values were obtained for FIRΔexon2 + p53 Abs compared to all AUC values of ESCC.

Figure 4.

Comparison of combined ROCs in ESCC patients. A, Overall diagnostic efficiency of seven Abs was evaluated by comparing ROC curves. AUC values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 7. Values are shown in descending order of AUC. B‐D, ROC analysis for the combination of candidate markers examined by the basis of Z score data normalized to SD of the quantified alpha count data of 95 patients with ESCC and 94 healthy subjects. Values are shown in descending order of AUC

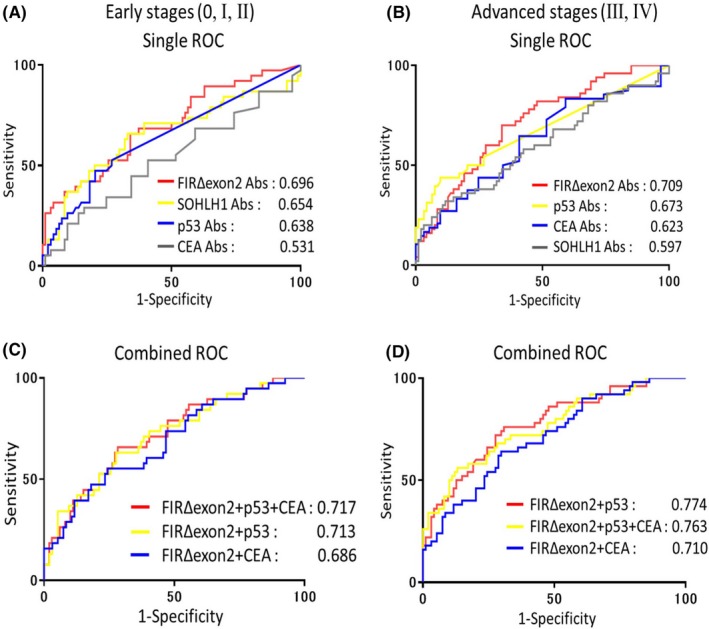

The AUC values obtained for cancer classified as early or advanced stage are shown in Figure 5. The highest AUC values were obtained for FIRΔexon2 Abs in both early and advanced stage cancers when compared with AUC values of other ESCC candidate markers. The AUC values of early stage cancers were as follows: FIRΔexon2, 0.696; KARS, 0.598; SNX15, 0.632; SOHLH1, 0.654; CFAP70, 0.627; p53, 0.638; and CEA, 0.531 (Figure 5A). For advanced stage cancers, AUC values were as follows: FIRΔexon2, 0.709; KARS, 0.525; SNX15, 0.568; SOHLH1, 0.597; CFAP70, 0.567; p53, 0.673; and CEA, 0.623 (Figure 5B). The AUC values of FIRΔexon2 Abs were higher in advanced stage cancers compared to early stage (Figure 5C,D). However, in early stage cancers, the combined AUC showed increased values. Furthermore, in early stage cancers, the early diagnosis efficiency increased when FIRΔexon2 Abs were combined with p53 Abs (AUC 0.713) or with p53 and CEA Abs (AUC 0.717). In advanced stage cancers, the diagnosis efficiency increased when FIRΔexon2 Abs were combined with p53 Abs (AUC 0.774).

Figure 5.

The Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) ROC curve analysis depicting the diagnosis efficiency of FIRΔexon2 Abs in combination with SOHLH1, CEA, and p53 Ab markers in ESCC patients. A, Area under the ROC curve (AUC) values of candidate markers for early stage ESCCs. B, AUC values of candidate markers for advanced stage ESCCs. C, ROC analysis depicting the diagnosis efficiency of FIRΔexon2 Abs in combination with CEA/p53 Ab markers for early stage ESCCs. D, ROC analysis depicting the diagnosis efficiency of FIRΔexon2 Abs in combination with CEA/p53 Ab markers for advanced stage ESCCs

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we identified potential novel diagnostic markers for ESCC using SEREX screening.10 Serum Ab markers were detected using purified GST‐fusion proteins as antigens. One hundred and eighty‐nine patients with various cancers were evaluated for the presence of several Abs. Patients with confirmed ESCC showed significantly higher levels of Abs against most SEREX antigens. Additionally, all 5 SEREX antigen markers identified were significantly higher in patients with ESCC compared to HDs. Similar results were obtained by ROC analysis. The AUC values were greater than 0.5912 for all markers, with the exception of KARS Abs when compared with CEA (Table 1). Furthermore, AUC values greater than 0.700 were observed for FIRΔexon2 Abs in patients with ESCC. It is conceivable that FIRΔexon2 Abs are common markers for ESCCs.23, 31, 32

The combined ROC analysis of candidate Abs with anti‐p53 Abs and CEA showed increased AUC values in the sera of patients with ESCC. Specifically, the combination of anti‐p53 and FIRΔexon2 Abs was shown to improve the diagnostic efficiency, thus aiding in the early detection of ESCC (Figure 4 and Table 2). Furthermore, the significance of ROCs among single or combined markers was examined through comparing the AUC by DeLong tests.46, 49 In all stages of ESCCs, FIRΔexon2 Abs + p53 Abs or FIRΔexon2 Abs + CEA or FIRΔexon2 Abs + CEA + p53 Abs were significantly higher than that of CEA alone (Table S3, middle column). Similarly, there was significance in early or advanced stages of ESCCs (Table S4). Therefore, FIRΔexon2 Abs with anti‐p53 Abs or CEA improves the specificity and sensitivity for screening ESCCs. Further prospective multi‐institutional studies comparing the sensitivity and specificity of this combinational detection approach will be required.28

Amplified luminescence proximity homogeneous assay is an excellent method for measuring Ab levels compared with ELISA because of its low variation, stable background, and high specificity. It does not involve plate‐washing steps; however, it involves mixing antigens with Abs in sera followed by the addition of donor and acceptor beads. For instance, Figure 1 showed highly reproducible results, including distributions, P values, and positive rates despite using different sets of sera from healthy donors and patients. AlphaLISA is a novel, recently developed method. After examining suitable AlphaLISA conditions in this study, we concluded that the incubation for 7‐21 days is the best to obtain specific antigen‐Ab reaction as well as to reduce noise background. The precise measurement offered by AlphaLISA might enable establishment of Ab markers, although most of the existing tumor diagnosis methods involved antigen markers, with the exception of the p53 marker. The measurement of Abs was more sensitive in comparison to the measurement of the antigen levels owing to the stability of IgG proteins and their amplification by repeated exposures to antigenic proteins.38 Prior to development, highly malignant tumors can induce necrosis, leading to the exposure of intracellular antigenic proteins to plasma. Therefore, using combinational Ab detection approaches could allow for the precise early detection of tumors.28 In this study, we explored and examined 5 SEREX antigen markers for improved efficiency in diagnosing ESCC. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to suggest that FIRΔexon2, KARS, SNX15, SOHLH1, and CFAP70 Abs are candidate markers for ESCC and offer promise for the future selection of potential diagnostic markers.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Satoshi Fudo, Ms. Kurumi Hayashi (Department of Physical Chemistry, Chiba University), and Ms. Nobuko Tanaka (Department of Laboratory Medicine, Chiba University Hospital) for their technical assistance, Dr. Hideo Shin (Department of Neurosurgery, Higashi Funabashi Hospital) for clinical sample collection, and Dr. Hirofumi Doi (Celish FD, Japan) for useful scientific discussion.

Kobayashi S, Hiwasa T, Ishige T, et al. Anti‐FIRΔexon2, a splicing variant form of PUF60, autoantibody is detected in the sera of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:2004–2013. 10.1111/cas.14024

REFERENCES

- 1. Rustgi A, El‐Serag HB. Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1472‐1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pennathur A, Gibson MK, Jobe BA, Luketich JD. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet. 2013;381:400‐412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin DC, Hao JJ, Nagata Y, et al. Genomic and molecular characterization of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:467‐473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sahin U, Türeci O, Schmitt H, et al. Human neoplasms elicit multiple specific immune responses in the autologous host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11810‐11813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakashima K, Shimada H, Ochiai T, et al. Serological identification of TROP2 by recombinant cDNA expression cloning using sera of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:1029‐1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kuboshima M, Shimada H, Liu TL, et al. Identification of a novel SEREX antigen, SLC2A1/GLUT1, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:463‐468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuboshima M, Shimada H, Liu TL, et al. Presence of serum tripartite motif‐containing 21 antibodies in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:380‐386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shimada H, Shiratori T, Yasuraoka M, et al. Identification of Makorin 1 as a novel SEREX antigen of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shimada H, Nakashima K, Ochiai T, et al. Serological identification of tumor antigens of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:77‐86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shimada H, Kuboshima M, Shiratori T, et al. Serum anti‐myomegalin antibodies in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:97‐103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kagaya A, Shimada H, Shiratori T, et al. Identification of a novel SEREX antigen family, ECSA, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Proteome Sci. 2011;9:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsushita K, Tomonaga T, Kajiwara T, et al. c‐myc suppressor FBP‐interacting repressor for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2009;14:3401‐3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pelengaris S, Khan M, Evan GI. Suppression of Myc‐induced apoptosis in beta cells exposes multiple oncogenic properties of Myc and triggers carcinogenic progression. Cell. 2002;109:321‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bazar L, Meighen D, Harris V, Duncan R, Levens D, Avigan M. Targeted melting and binding of a DNA regulatory element by a transactivator of c‐myc. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8241‐8248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Michelotti GA, Michelotti EF, Pullner A, Duncan RC, Eick D, Levens D. Multiple single‐stranded cis elements are associated with activated chromatin of the human c‐myc gene in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2656‐2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zubaidah RM, Tan GS, Tan SB, Lim SG, Lin Q, Chung MC. 2‐D DIGE profiling of hepatocellular carcinoma tissues identified isoforms of far upstream binding protein (FUBP) as novel candidates in liver carcinogenesis. Proteomics. 2008;8:5086‐5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malz M, Weber A, Singer S, et al. Overexpression of far upstream element binding proteins: a mechanism regulating proliferation and migration in liver cancer cells. Hepatology. 2009;50:1130‐1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quinn LM. FUBP/KH domain proteins in transcription: back to the future. Transcription. 2017;8:185‐192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu J, Akoulitchev S, Weber A, et al. Defective interplay of activators and repressors with TFIH in xeroderma pigmentosum. Cell. 2001;104:353‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kitamura A, Matsushita K, Takiguchi Y, et al. Synergistic effect of non‐transmissible Sendai virus vector encoding the c‐myc suppressor FUSE‐binding protein‐interacting repressor plus cisplatin in the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1366‐1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kano M, Matsushita K, Rahmutulla B, et al. Adenovirus‐mediated FIR demonstrated TP53‐independent cell‐killing effect and enhanced antitumor activity of carbon‐ion beams. Gene Ther. 2016;23:50‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsushita K, Tomonaga T, Shimada H, et al. An essential role of alternative splicing of c‐myc suppressor FUSE‐binding protein‐interacting repressor in carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1409‐1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hastings ML, Allemand E, Duelli DM, Myers MP, Krainer AR. Control of pre‐mRNA splicing by the general splicing factors PUF60 and U2AF(65). PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Page‐McCaw PS, Amonlirdviman K, Sharp PA. PUF60: a novel U2AF65‐related splicing activity. RNA. 1999;5:1548‐1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang YM, Yang HB, Shi JL, et al. The prevalence and clinical significance of anti‐PUF60 antibodies in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:1573‐1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fiorentino DF, Presby M, Baer AN, et al. PUF60: a prominent new target of the autoimmune response in dermatomyositis and Sjögren's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1145‐1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kobayashi S, Hiwasa T, Arasawa T, et al. Identification of specific and common diagnostic antibody markers for gastrointestinal cancers by SEREX screening using testis cDNA phage library. Oncotarget. 2018;9:18559‐18569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kobayashi S, Hoshino T, Hiwasa T, et al. Anti‐FIRs (PUF60) auto‐antibodies are detected in the sera of early‐stage colon cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:82493‐82503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matsushita M, Hoshino T. Novel diagnosis and therapy for hepatoma targeting HBV‐related carcinogenesis through alternative splicing of FIR (PUF60)/FIRΔexon2. Hepatoma Res. 2018;4:61. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ogura Y, Hoshino T, Tanaka N, et al. Disturbed alternative splicing of FIR (PUF60) directed cyclin E overexpression in esophageal cancers. Oncotarget. 2018;9:22929‐22944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kajiwara T, Matsushita K, Itoga S, et al. SAP155‐mediated c‐myc suppressor far‐upstream element‐binding protein‐interacting repressor splicing variants are activated in colon cancer tissues. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:149‐156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takahashi K, Kanazawa H, Chan H, et al. A case of esophageal carcinoma metastatic to the mandible and characterization of two cell lines (T.T. T.Tn.). Jpn J Oral Maxilofac Surg. 1990;36:307‐316. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shimada H, Shimizu T, Ochiai T, et al. Preclinical study of adenoviral p53 gene therapy for esophageal cancer. Surg Today. 2001;31:597‐604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Machida T, Kubota M, Kobayashi E, et al. Identification of stroke‐associated‐antigens via screening of recombinant proteins from the human expression cDNA library (SEREX). J Transl Med. 2015;13:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang H, Zhang XM, Tomiyoshi G, et al. Association of serum levels of antibodies against MMP1, CBX1, and CBX5 with transient ischemic attack and cerebral infarction. Oncotarget. 2018;9:5600‐5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matsutani T, Hiwasa T, Takiguchi M, et al. Autologous antibody to src‐homology 3‐domain GRB2‐like 1 specifically increases in the sera of patients with low‐grade gliomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yoshida Y, Wang H, Hiwasa T, et al. Elevation of autoantibody level against PDCD11 in patients with transient ischemic attack. Oncotarget. 2018;9:8836‐8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hiwasa T, Zhang XM, Kimura R, et al. Association of serum antibody levels against TUBB2C with diabetes and cerebral infarction. Integ Biomed Sci. 2015;1:49‐63. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goto K, Sugiyama T, Matsumura R, et al. Identification of cerebral infarction‐specific antibody markers from autoantibodies detected in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Mol Biomark Diagnos. 2015;6:2. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hiwasa T, Machida T, Zhang XM, et al. Elevated levels of autoantibodies against ATP2B4 and BMP‐1 in sera of patients with atherosclerosis‐related diseases. Immunome Res. 2015;11:097. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nakamura R, Tomiyoshi G, Shinmen N, et al. An anti‐deoxyhypusine synthase antibody as a marker of atherosclerosis‐related cerebral infarction, myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. SM Atheroscler J. 2017;1:1001. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hiwasa T, Tomiyoshi G, Nakamura R, et al. Serum SH3BP5‐specific antibody level is a biomarker of atherosclerosis. Immunome Res. 2017;13:132. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chiu RW, Chan KC, Gao Y, et al. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of fetal chromosomal aneuploidy by massively parallel genomic sequencing of DNA in maternal plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20458‐20463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Matsuda H, Mizumura S, Nagao T, et al. Automated discrimination between very early Alzheimer disease and controls using an easy Z‐score imaging system for multicenter brain perfusion single‐photon emission tomography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:731‐736. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke‐Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837‐845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sun X, Xu W. Fast implementation of DeLongs algorithm for comparing the areas under correlated receiver operating characteristic curves. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2014;21:1389‐1393. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open‐source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Venkatraman ES. A permutation test to compare receiver operating characteristic curves. Biometrics. 2000;56:1134‐1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rahmutulla B, Matsushita K, Satoh M, et al. Alternative splicing of FBP‐interacting repressor coordinates c‐Myc, P27Kip1/cyclinE and Ku86/XRCC5 expression as a molecular sensor for bleomycin‐induced DNA damage pathway. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2404‐2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kim DG, Choi JW, Lee JY, et al. Interaction of two translational components, lysyl‐tRNA synthetase and p40/37LRP, in plasma membrane promotes laminin‐dependent cell migration. FASEB J. 2012;26:4142‐4159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Motzik A, Nechushtan H, Foo SY, Razin E. Non‐canonical roles of lysyl‐tRNA synthetase in health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:726‐731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ofir‐Birin Y, Fang P, Bennett SP, et al. Structural switch of lysyl‐tRNA synthetase between translation and transcription. Mol Cell. 2013;49:30‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Danson C, Brown E, Hemmings OJ, et al. SNX15 links clathrin endocytosis to the PtdIns3P early endosome independently of the APPL1 endosome. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:4885‐4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Phillips SA, Barr VA, Haft DH, Taylor SI, Haft CR. Identification and characterization of SNX15, a novel sorting nexin involved in protein trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5074‐5084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Suzuki H, Ahn HW, Chu T, et al. SOHLH1 and SOHLH2 coordinate spermatogonial differentiation. Dev Biol. 2012;361:301‐312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pangas SA, Choi Y, Ballow DJ, et al. Oogenesis requires germ cell‐specific transcriptional regulators Sohlh1 and Lhx8. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8090‐8095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shamoto N, Narita K, Kubo T, Oda T, Takeda S. CFAP70 is a novel axoneme‐binding protein that localizes at the base of the outer dynein arm and regulates ciliary motility. Cells. 2018;7:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials