ABSTRACT

Two large-scale mouse gene knockout phenotyping campaigns have provided extensive data on the functions of thousands of mammalian genes. The ongoing International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC), with the goal of examining all ∼20,000 mouse genes, has examined 5115 genes since 2011, and phenotypic data from several analyses are available on the IMPC website (www.mousephenotype.org). Mutant mice having at least one human genetic disease-associated phenotype are available for 185 IMPC genes. Lexicon Pharmaceuticals' Genome5000™ campaign performed similar analyses between 2000 and the end of 2008 focusing on the druggable genome, including enzymes, receptors, transporters, channels and secreted proteins. Mutants (4654 genes, with 3762 viable adult homozygous lines) with therapeutically interesting phenotypes were studied extensively. Importantly, phenotypes for 29 Lexicon mouse gene knockouts were published prior to observations of similar phenotypes resulting from homologous mutations in human genetic disorders. Knockout mouse phenotypes for an additional 30 genes mimicked previously published human genetic disorders. Several of these models have helped develop effective treatments for human diseases. For example, studying Tph1 knockout mice (lacking peripheral serotonin) aided the development of telotristat ethyl, an approved treatment for carcinoid syndrome. Sglt1 (also known as Slc5a1) and Sglt2 (also known as Slc5a2) knockout mice were employed to develop sotagliflozin, a dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibitor having success in clinical trials for diabetes. Clinical trials evaluating inhibitors of AAK1 (neuropathic pain) and SGLT1 (diabetes) are underway. The research community can take advantage of these unbiased analyses of gene function in mice, including the minimally studied ‘ignorome’ genes.

KEY WORDS: Knockout mice, Mouse models, Phenotyping, Phenomics, Translational medicine

Summary: Large-scale, focused phenotyping campaigns provide data for thousands of mutant mouse genes, yielding key information for understanding rare human diseases and for developing novel drug therapies.

Introduction

Understanding gene function can explain the disease phenotypes observed in carriers of common genetic variants and deleterious mutations. Great progress is being made, deciphering the functions of the ∼20,000 human genes, but the actions of many genes remain poorly understood. For example, the Undiagnosed Diseases Network and other DNA sequencing efforts can typically identify gene mutations for one-third of patients with unknown rare genetic diseases (Splinter et al., 2018). The genes, and their actions, responsible for the remaining patients remain unknown. Identifying the actions and biochemical pathways of disease genes provides insights for potential therapies. Although imperfect, mice are the best-established models for human disease (Justice and Dhillon, 2016; Perlman, 2016; Sundberg and Schofield, 2018; Nadeau and Auwerx, 2019). This article summarizes data from two large-scale mouse gene knockout phenotyping campaigns: the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals' Genome5000™ program.

Both campaigns employed reverse genetics, the approach that relies on analyzing the phenotypes that result from the inactivation of specific genes to provide information on the physiological functions of these genes, to generate knockout mouse strains. Forward genetics approaches, involving the identification of the genes responsible for mouse phenotypes resulting from spontaneous mutations (Davisson et al., 2012) or chemical mutagenesis (Probst and Justice, 2010; Arnold et al., 2012; Sabrautzki et al., 2012; Potter et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018), have also made major contributions to our understanding of genetic disease. Besides identifying inactivating gene mutations, forward genetics approaches often identify hypomorphic, gain-of-function and dominant-negative mutations. For example, The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) employed whole-exome sequencing to decipher spontaneous pathogenic mutations in 124 mouse strains (Fairfield et al., 2015; Palmer et al., 2016).

Mouse gene knockout phenotyping

Although examining mutant mice in individual laboratories has uncovered the functions of many genes, such piecemeal studies have several limitations. First, individual research groups often focus on the systems in which they have interest, hypotheses and experimental expertise. As a result, they can miss or ignore additional phenotypes. For example, a behavior laboratory can easily overlook concurrent immune disorders. Second, since research groups tend to individualize experimental techniques, comparisons among different laboratories can be difficult. Mouse strains, sex and age, along with assays and computational analyses, also vary. Third, there is a strong bias in the community to repeatedly study well-characterized genes, leaving thousands of genes, known as the ‘ignorome’ or the ‘dark genome’, unexplored (Edwards et al., 2011; Pandey et al., 2014; Oprea et al., 2018; Stoeger et al., 2018). The Mouse Genome Informatics database (Eppig, 2017) includes 13,924 genes with published mutant alleles in mice (data correct as of 19 February 2019), indicating that 6000 mouse genes remain unexplored and are therefore part of the ignorome.

Large-scale mutant mouse phenotyping campaigns that employ a panel of assays covering a wide range of phenotypes and apply standardized experimental protocols and statistical analyses can address these limitations. The thousands of genes examined in these projects include both ignorome and previously characterized genes. Technical staff generally have no knowledge of purported gene functions, which minimizes subconscious bias, and the large amounts of data collected from wild-type mice allow tracking of possible variations from normal values over time (Moore et al., 2018a).

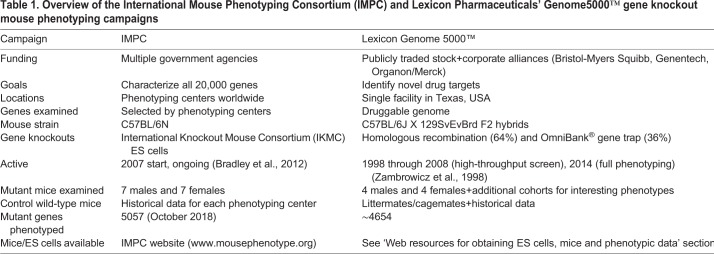

Two large-scale mouse gene knockout phenotyping campaigns have been undertaken: Lexicon Pharmaceuticals' Genome5000™ campaign, designed to identify novel drug targets, and the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC), which aims to characterize mutant phenotypes for all ∼20,000 mammalian genes. As summarized in Table 1, these two campaigns have many similarities but also differences.

Table 1.

Overview of the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals' Genome5000™ gene knockout mouse phenotyping campaigns

Lexicon's high-throughput phenotyping analyses were performed between 2001 and the end of 2008, and included alliances with Bristol-Myers Squibb (Toyn et al., 2010; Kostich et al., 2016), Genentech (Tang et al., 2010) and Organon/Merck. The ongoing IMPC effort evolved from and includes data for 449 genes obtained during earlier European Mouse Disease Clinic (EUMODIC) and Sanger Mouse Genetics Program (MGP) mutant mouse phenotyping campaigns (Ayadi et al., 2012; White et al., 2013; de Angelis et al., 2015). Individual IMPC phenotyping centers select the genes they examine based on institutional investigator interests. Two focused mouse gene knockout phenotyping campaigns included examinations of 36 genes coding for glycan-binding proteins and glycosyltransferases (Orr et al., 2013) and 54 testes-expressed genes for male fertility (Miyata et al., 2016). In the early 2000s, Deltagen generated 750 mouse gene knockout lines using standard homologous recombination techniques (Moore, 2005) and phenotypic data are publicly available for 134 of these knockout lines (Table S1).

The IMPC effort utilizes murine embryonic stem (ES) cells generated by the International Knockout Mouse Consortium (IKMC) (Bradley et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2018). The IMPC phenotyping screen generally examines seven male and seven female mutant mice, with comparisons to phenotyping center-specific male and female historical control wild-type mice, which are shared among all genes examined (Meehan et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2018). An example of IMPC control data for body bone mineral density (BMD) is provided in Fig. S1. Lexicon's effort utilized ES cells generated by gene-trap mutagenesis using the OmniBank® I library (Abuin et al., 2007; Hansen et al., 2008) or homologous recombination involving a λ-phage knockout shuttle system (Wattler et al., 1999). Phenotypes of Adipor1, Angptl4, Ptprg, Rpn13 (also known as Adrm1) and Tph1 mouse knockout lines generated independently via both ES cell technologies were identical. The Lexicon primary phenotyping screen generally examined four male and four female mutant mice, with comparisons to both littermate/cagemate and historical control wild-type mice. The parents of the mutant mice examined initially were subsequently mated a second time to provide a second cohort of mice for possible replication studies. The primary screen clearly identified dramatic phenotypes (Alpk3, Brs3, Ksr2, Lrrk1, Mc4r and Sost), with milder phenotypes confirmed or refuted with the second cohort. This approach follows the Bayesian statistical paradigm. If phenotypic replication was successful and the gene encoded a potential drug target, multiple additional cohorts of mutant mice were generated for sophisticated analyses. For example, more than 700 homozygous mutant mice were generated for Aak1, Dagla, Ksr2, Ptprg, Sglt1 (also known as Slc5a1), Sglt2 (also known as Slc5a2), Stk4 and Tph1 genes.

Both Lexicon and the IMPC employ similar phenotyping screens for audiology, behavior, blood cell counts, cardiology, body BMD and composition, immunology, metabolism, ophthalmology, radiology and serum chemistry. When gene knockout was lethal, yielding no adult homozygous mice, both campaigns examined mutant heterozygous mice. Beyond the common screening assays discussed above, Lexicon examined cortical and trabecular bone architecture by micro computed tomography (microCT) (Brommage et al., 2014), pain sensitivity by hot plate and formalin skin responses (Kostich et al., 2016), neuronal amyloid-β levels (Toyn et al., 2010) and comprehensive histopathology (Schofield et al., 2012). Metabolic responses to feeding a high-fat diet were analyzed in a second cohort (Brommage et al., 2008). Whereas IMPC extends the embryonic lethal analysis to time of death and high-throughput optical projection and microCT imaging (Dickinson et al., 2016), Lexicon did not examine the developmental abnormalities responsible for embryonic lethality.

The IMPC publishes detailed mutant mouse phenotype data. These publications include histopathology for 50 genes (Adissu et al., 2014); plasma metabolic profiling for 62 genes (Probert et al., 2015); skin, hair and nail abnormalities for 169 genes (Sundberg et al., 2017); developmental abnormalities for 401 embryonic-lethal knockout lines (Dickinson et al., 2016); skin data from 500+ genes (DiTommaso et al., 2014; Liakath-Ali et al., 2014); whole-mount LacZ reporter tissue expression profiles (Armit, 2015) in adult mice for 313 (West et al., 2015) and 424 (Tuck et al., 2015) genes; hearing data for 3006 genes (Bowl et al., 2017); metabolic phenotyping for 2016 genes (Rozman et al., 2018); and ophthalmic data for 4364 genes (Moore et al., 2018b). A manuscript summarizing IMPC bone data and relationships to human skeletal diseases is in preparation. The IMPC website (www.mousephenotype.org) provides comprehensive mutant mouse phenotype data in a readily searchable format (Koscielny et al., 2014). Updates of ongoing progress in IMPC mouse phenotyping continue, with Release 9.2 (5614 phenotyped genes) published in January 2019.

All high-throughput screens have false positives and false negatives (Karp et al., 2010) and ‘…it has never been easier to generate high-impact false positives than in the genomic era’ (MacArthur, 2012). The occurrence of false negatives can be estimated by the ability to identify the expected phenotypes arising from knockouts of benchmark genes, which are associated with well-established human and mouse mutant phenotypes. Examples of successful benchmark gene confirmation include Brs3, Cnr1 and Mcr4 in Lexicon's obesity screen (Brommage et al., 2008), and Crtap, Lrp5, Ostm1, Src and Sost in Lexicon's bone screen (Brommage et al., 2014). Conversely, researchers can detect false positives by phenotyping additional cohorts of mutant mice. The IMPC campaign provides data for the primary screen only, and statistical modeling calculations (Karp et al., 2010) estimate an 11.4% false-positive rate averaged among all IMPC phenotyping assays. Lexicon's primary screen included fewer mice than that of the IMPC, and many false positives, subsequently identified with secondary screens, were observed.

Complete and variably penetrant lethality are common in gene knockout mice (Wilson et al., 2017). The IMPC defines subviable mutant lines as having fewer (<12.5% of the litter) than the expected 25% surviving homozygous mice resulting from heterozygous crosses (http://www.mousephenotype.org/data/embryo). The latest IMPC data for 4969 mutant lines show 24% preweaning lethality and 10% subviability. Lexicon observed ∼16% preweaning lethality among 4654 mutant lines (Brommage et al., 2014).

Two IMPC phenotyping centers (Freudenthal et al., 2016; Dyment et al., 2016; Rowe et al., 2018) perform specialized skeletal analyses beyond the body BMD and radiology data obtained as part of the high-throughput screen (Table S1). Combined bone quantitative X-ray microradiography (Butterfield et al., 2019) and bone breaking strength data are available for 100 genes, with skeletal phenotypes observed for nine genes (Bassett et al., 2012). Gene knockout of the murine Slc20a2 phosphate transporter (Beck-Cormier et al., 2019) results in skeletal defects and brain calcification, mimicking the homologous human genetic disease. Integration of IMPC mouse bone data and human genome-wide association study (GWAS) of heel bone BMD and fracture data from the UK Biobank identified variants in GPC6 (Kemp et al., 2017) and DAAM2 (Morris et al., 2019) as key determinants of skeletal health.

A summary of Lexicon's phenotyping campaign (∼4654 genes, with 3762 viable adult homozygous gene knockout lines undergoing bone phenotyping) was published in 2014 (Brommage et al., 2014). Published phenotypes involving multiple cohorts of knockout mice are available for 100 genes summarized below.

Modeling human Mendelian genetic disorders

Mutant mice contribute to our understanding of the mechanisms responsible for human genetic disorders. The IMPC performs an automated comparison of mutant mouse phenotypes to over 7000 rare human diseases in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) and Orphanet databases. The comprehensive 2017 update (Meehan et al., 2017) summarizes IMPC disease model discovery findings. Briefly, of the 3328 IMPC mouse genes examined, 621 had previous MGI mouse model annotations, with 385 genes (62%) having common observed phenotypes. Importantly, 90% (8984 of 9942) of the gene-phenotype annotations described by the IMPC had not previously been described in the literature. From the OMIM or Orphanet databases, 889 known rare disease-gene associations have an orthologous IMPC mouse mutant displaying at least one phenotype. These 889 associations involve 185 IMPC genes for which mutant mice showed at least one human disease-associated phenotype. Details on these data are available in supplementary tables 1-4 in Meehan et al. (2017). Updates to these analyses are provided within the ‘Human Diseases’ section of the IMPC website.

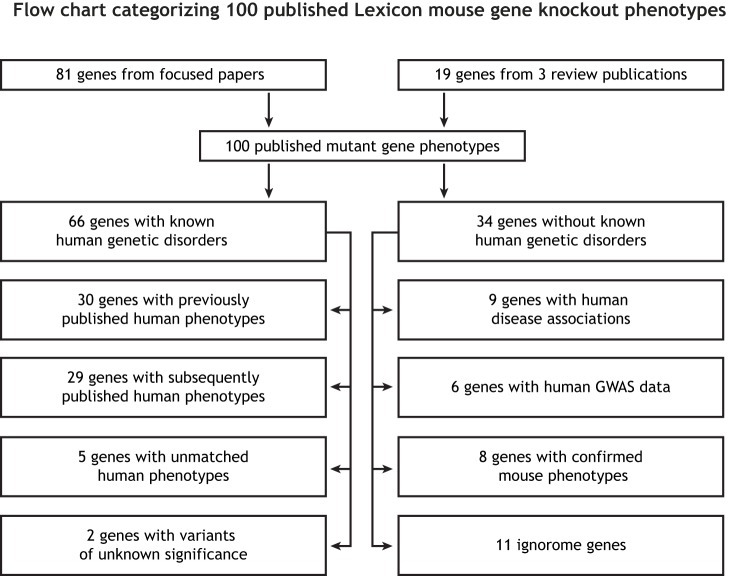

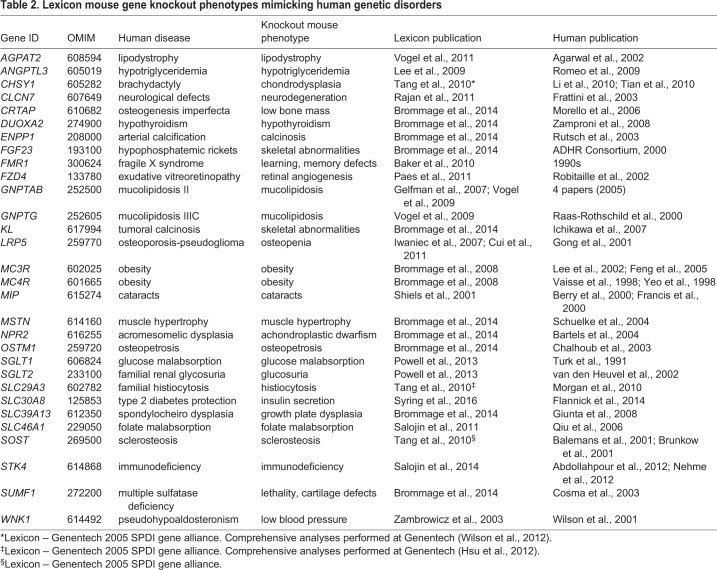

Lexicon published mouse knockout phenotypes for 100 genes (Fig. 1; Table S2) in both focused papers (N=81) and summaries (N=19) on obesity (Brommage et al., 2008) and bone phenotypes (Brommage et al., 2014), and the Genentech Secreted Protein Discovery Initiative (SPDI) gene alliance (Tang et al., 2010). Manual annotation of the PubMed database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) identified human Mendelian disease phenotypes for 66 of these 100 mouse genes, with the remaining 34 having no known associated human Mendelian genetic disorder. Table 2 lists 30 genes for which Lexicon's mutant mouse data support previously identified human phenotypes. All 30 genes have an OMIM disease designation.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart categorizing 100 published Lexicon mouse gene knockout phenotypes. We grouped these based on known or unknown human-mouse gene associations.

Table 2.

Lexicon mouse gene knockout phenotypes mimicking human genetic disorders

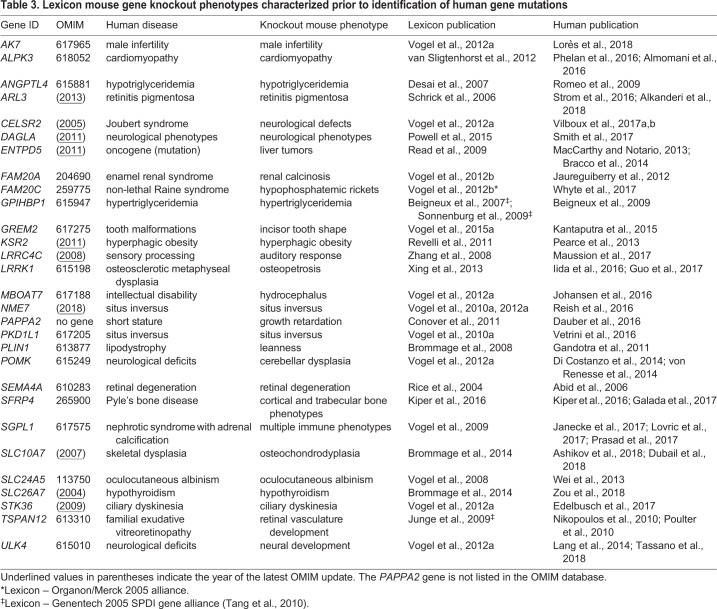

Importantly, 29 mutant mouse phenotypes mimicking human disease phenotypes were characterized and published prior to the identification of their orthologous human disease genes (Table 3). Eighteen of these 29 genes have an OMIM disease designation, and OMIM summaries for many of the remaining 11 genes are outdated. At the time of Lexicon's mouse phenotypic analyses, most of these 29 genes were minimally studied ignorome genes.

Table 3.

Lexicon mouse gene knockout phenotypes characterized prior to identification of human gene mutations

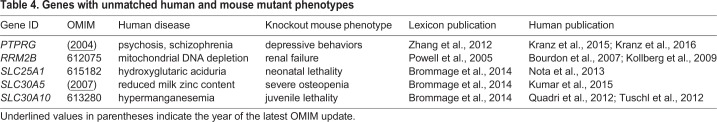

ADIPOR1 (Rice et al., 2015) and HDAC4 (Rajan et al., 2009) are classified as variants of unknown significance in OMIM, as subsequent human studies did not confirm the initial disease phenotype-gene associations observed in humans (Zhang et al., 2016) and mice. Hdac4 knockout mice are presently in the IMPC phenotyping queue. Adipor1 mice showed abnormal retinal morphology in both Lexicon and IMPC screens. Diverging human and mouse phenotypes have been described for five genes [PTPRG (Zhang et al., 2012), RRM2B (Powell et al., 2005), and SLC25A1, SLC30A5 and SLC30A10 (Brommage et al., 2014)], which can result from incomplete human and/or mouse phenotypic evaluations (Table 4). For example, human SLC30A5 mutations affecting a zinc transporter reduce human breast milk zinc content without other clinical observations (Kumar et al., 2015), whereas Slc30a5 mutant mice have low bone mass (Inoue et al., 2002; Brommage et al., 2014), but mouse milk composition was not examined. In the IMPC campaign, Slc30a10 mice are currently in the phenotyping queue, Slc25a1 mice exhibited preweaning lethality and the other three genes have not been examined yet.

Table 4.

Genes with unmatched human and mouse mutant phenotypes

The 34 Lexicon mouse phenotypes described without corresponding published human Mendelian genetic disorders fall into several categories (Table 5). Mouse mutant phenotypes for Slc6a4 [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) drug target] and Tph1 (carcinoid syndrome drug target) have been examined by independent laboratories, but not by the IMPC. Human GWAS data exist for EPHA6, FADS1, KCNK16, NOTUM, TPH2 and WNT16, with the IMPC having examined Epha6, Fads1, Notum and Wnt16 mutant mice and observing preweaning lethality in Notum and Wnt16 knockout mice. Multiple studies indicate that ATG4B, CLDN18, LIMK2, MDM4, MKP1 (also known as DUSP1), RPN13 and UCHL5 are human oncogenes, with the IMPC having examined Atg4b, Cldn18, Limk2, Mkp1 and Uchl5 mutant mice and observing preweaning lethality in Limk2 and Uchl5 knockout animals. There is minimal published information for 11 ignorome genes (Aak1, Ak8, Dpcd, Itfg2, Kif27, Kirrel1, Nme5, Tmem218, Tmub1, Tomm5 and Ttll1), and the IMPC examined only preweaning lethal Ttll1 mutant mice. Independently published mouse knockout data exist for eight genes (Brs3, Fam20b, Pik3c2a, Rock1, Rock2, Sh2d3c, Slc30a7 and Spns2), with the IMPC having examined Pik3c2a, Rock1 and Spns2 mutant mice, observing preweaning lethality in Pik3c2a and Rock1 mutant mice.

Table 5.

Mouse phenotypes without known human Mendelian genetic disorders

Of the 100 Lexicon genes summarized in Fig. 1, embryonic lethality was observed in Fam20b, Mdmx and Wnk1 knockout mice, perinatal lethality in Kirrel1 knockout mice, and juvenile lethality in Arl3, Clcn7, Fgf23, Klotho, Npr2, Ostm1, Slc4a1 and Sumf1 knockout mice. Subviability, defined as a deviation from the expected 1-2-1 Mendelian ratio of wild-type, heterozygous and homozygous mice from heterozygous crosses at P<0.001 by Chi-squared testing, was observed in Angptl4 (754, 17%), Notum (931, 19%), Pkd1l1 (61, 10%), Pomk (395, 10%), Rock1 (197, 15%), Rock2 (227, 4%), Rpn13 (39, 9%) and Uchl5 (644, 14%) mice. Numbers in parentheses indicate observed numbers of wild-type mice and percentages of homozygous mutant mice, respectively.

Studies in mutant mice can also provide guidance for treating human genetic diseases. For example, Lexicon (Iwaniec et al., 2007) and others (Sawakami et al., 2006) showed that teriparatide treatment increases bone mass in Lrp5 gene knockout mice with low bone mass. Similarly, teriparatide treatment increased BMD in a patient with osteoporosis pseudoglioma syndrome resulting from an inactivating LRP5 mutation (Arantes et al., 2011).

IMPC – Lexicon comparisons

These two successful phenotyping campaigns had different objectives, funding and approaches to phenotypic screening (Table 1), and comprehensive comparisons are beyond the scope of this article. Of the 100 Lexicon genes discussed here, 36 were also examined by the IMPC. Preweaning lethality was observed for 15 genes (Fam20c, Fzd4, Limk2, Mboat7, Notum, Pik3c2a, Rock1, Sgpl1, Slc25a1, Slc46a1, Stk36, Sumf1, Ttll1, Uchl5 and Wnt16) in the IMPC, but not the Lexicon, phenotypic analyses. The OMIM autosomal-recessive disease genes FAM20C, MBOAT7, SGPL1, SLC46A1 and SUMF1 are not expected to exhibit disease phenotypes in the heterozygous mutant mice examined by the IMPC. Lexicon examined F2 hybrid C56BL/6J X 129SvEv-Brd mice, and hybrid vigor presumably contributed to better viability compared to the purebred C57BL/6N mice examined by the IMPC. The lower rate of lethality across all genes examined (∼16% for Lexicon versus 25% for IMPC) is consistent with this hypothesis. Incomplete penetrance is common in human inherited diseases (Cooper et al., 2013) and variations in modifier genes likely contribute to this variable penetrance (Riordan and Nadeau, 2017).

Of the 36 genes examined in both phenotyping campaigns, 17 genes model human Mendelian disease. Both campaigns provided robust mouse data consistent with human genetic disorders involving mutations of ALPK3, ANGPT4, DAGLA, DUOXA2, LRRK1 and SLC24A5. Lrrk1 mice have the highest body volumetric BMD and BMD values in the Lexicon and IMPC screens, respectively (Fig. S1). Preweaning lethality and/or subviability of homozygous mice in the IMPC screen for Fam20c, Fzd4, Grem2, Mboat7, Sgpl1, Slc25a1, Slc46a1 and Sumf1 precluded the evaluation of homozygous knockout phenotypes for these genes. In contrast to observations by Lexicon, the IMPC did not observe soft tissue calcification in Fam20a mice, situs inversus in Nme7 mice, nor any phenotypes in Sglt2 (only immunological parameters were examined) or Slc30a8 mice. Human gene mutation phenotypes for FAM20A (enamel renal syndrome), NME7 (situs inversus), SGLT2 (familial renal glycosuria) and SLC30A8 (resistance to Type 2 diabetes) are consistent with Lexicon's mutant mouse phenotypes.

Lexicon's extended phenotyping allowed characterization of human disease phenotypes not measured in the initial high-throughput screening assays. For example, human DUOXA2 (Zamproni et al., 2008) and SLC26A7 (Zou et al., 2018) mutations result in hypothyroidism, and Lexicon observed abnormal thyroid gland histology in both gene knockouts. Moreover, Lexicon's Slc26a7 mice had reduced circulating thyroxine levels (Brommage et al., 2014).

Identifying novel drug targets

Studying human genetic disorders (Plenge et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2015; Williams, 2016) in conjunction with knockout mice (Zambrowicz and Sands, 2003) can identify previously unknown tractable targets and lead to effective drugs. PCSK9 is an example of this strategy, as knowledge that human inactivating mutations result in hypocholesterolemia led to the development of neutralizing antibodies to treat this condition (Jaworski et al., 2017). Pcsk9 knockout mice are also hypocholesterolemic (Rashid et al., 2005) and blood cholesterol levels are halved in IMPC mice.

Unlike the genome-wide effort of the IMPC, Lexicon's choice of genes for knockout mouse analyses emphasized the druggable genome (Plewczynski and Rychlewski, 2009; Finan et al., 2017; Santos et al., 2017), which includes enzymes, receptors, ligands, channels and secreted proteins. Ideally, drugs should influence disease processes without adversely affecting healthy tissues. In addition to identifying novel drug targets from beneficial mutant phenotypes, human genetic diseases and global gene knockout mice quickly identify or, preferably rule out, the possible adverse phenotypes that are likely to contribute to secondary drug target effects. For example, hypocholesterolemic subjects with inactivating PCKS9 mutations and IMPC Pcks9 mutant mice have no unexpected health problems related to this mutation, suggesting that therapeutic inhibition of PCKS9 activity should be safe. Generally, once this approach identifies novel drug targets, the preclinical drug development pipeline involves establishing robust enzymatic or binding assays, screening chemical libraries, optimization of chemical structures for potency and pharmacokinetic properties, followed by increasingly sophisticated animal pharmacology and toxicology studies. Thus, Lexicon stopped examining new mouse gene knockouts after December 2008 and stopped all basic research after January 2014 to focus on clinical development of small molecule drugs against selected targets previously identified in its gene knockout phenotyping campaign.

Lexicon's preclinical drug development program included the generation of neutralizing antibodies against ANGPTL3 (Lee et al., 2009), ANGPTL4 (Desai et al., 2007), DKK1 (Brommage et al., 2014), FZD4 (Paes et al., 2011) and NOTUM (Brommage et al., 2019). Treating wild-type mice with each antibody successfully replicated the phenotypes observed in knockout mice. Subsequent work by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals demonstrated the efficacy of anti-ANGPTL3 antibodies for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia in human patients (Dewey et al., 2017). In addition to providing phenotypic information, gene knockout mice provide two advantages in antibody generation and characterization. First, producing antibodies should, theoretically, be more efficient in specific gene knockout compared to wild-type mice, as the knockout mouse immune systems have never been exposed to the immunizing proteins. Second, lack of antibody specificity is a major experimental problem, and the ‘… most stringent control for antibody specificity requires comparison of antibody reactivity in wild-type tissues or cells to reactivity in knockout animals…’ (Schonbrunn, 2014). Lexicon demonstrated the specificities of its anti-ANGPTL3 and anti-ANGPTL4 antibodies by showing lack of reactivity to tissues from the corresponding gene knockout mice.

In addition to antibodies, Lexicon developed small-molecule chemical inhibitors to 12 targets and information on these targets is provided in Table S3. Orally active inhibitors of AAK1, SGLT1, SGLT2, SGPL1, SLC6A7 and TPH1 entered human clinical trials. Lexicon's peripheral serotonin synthesis inhibitors LX1031 and telotristat ethyl (both acting on tryptophan hydroxylase 1 encoded for by the TPH1 gene) showed efficacy in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome (Brown et al., 2011) and carcinoid syndrome (Kulke et al., 2017), respectively. Telotristat ethyl was approved for the treatment of carcinoid syndrome in 2017. Neither drug crosses the blood-brain barrier to inhibit the neuronal TPH2 serotonin-synthesizing enzyme. Sotagliflozin, a dual SGLT1/SGLT2 glucose transport inhibitor, showed efficacy in Phase 3 trials for Type 1 diabetes (Garg et al., 2017) and in Phase 2 trials for Type 2 diabetes (Rosenstock et al., 2015), and is currently being developed, in collaboration with Sanofi, for both indications. Early clinical development is underway examining inhibitors of SGLT1 for Type 2 diabetes (Goodwin et al., 2017) and AAK1 for neuropathic pain (Kostich et al., 2016).

Although drug development is not formally part of its mission or funding, the IMPC generates important knowledge for drug target identification and precision medicine initiatives (Lloyd et al., 2015). Unlike Lexicon, the main goal of the IMPC is not drug development. However, we believe that its data and collaborative nature are an unmatched resource for future downstream work, both aimed at improving our fundamental understanding of mammalian gene function and at applying this knowledge to treatment of human genetic diseases.

Conclusions

The IMPC and Lexicon mouse gene knockout phenotyping campaigns provide key data for scientists studying mouse and human genomics. By continually updating its online database, the IMPC increasingly characterizes ignorome genes. The future success of the IMPC in identifying gene functions of significance to human health can be expected based on the results of Lexicon's successful mutant mouse phenotyping efforts. Lexicon's clinical drug development efforts, aiming for approval of SGLT1, SGLT2 and AAK1 inhibitors, continue and their success should help patients with diabetes and neuropathic pain. We anticipate that future work will develop additional drugs from Lexicon's knowledge base and, with adequate support, that of the IMPC. Both campaigns are expected to continue to contribute key mouse data for researchers studying ignorome genes associated with human genetic diseases.

Although this article focuses on published results, we stress that networking and presenting preliminary mouse data at conferences facilitates interactions with scientists working in human genomics and can contribute to collaborations ultimately resulting in publication of newly identified human genetic data. Successful examples of this process include FAM20A, GREM2 (Kantaputra et al., 2015), KSR2 (Pearce et al., 2013) and SFRP4 (Kiper et al., 2016), and GWAS data for WNT16 (Medina-Gomez et al., 2012; Zheng et al., 2012; Wergedal et al., 2015). Lexicon collaborated with academic scientists on many projects, and IMPC collaborations with academia and pharma should be encouraged. Recent publications involving IMPC mouse bone data and human data from the UK Biobank (Kemp et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2019) should stimulate additional collaborations in the future.

We encourage scientists to visit the IMPC website for further understanding of the actions of genes of interest. As Francis Collins, Director of the US National Institutes of Health, stated in 2006, ‘A graduate student shouldn't spend a year making a knockout that's already been made. It's not a good use of resources’ (Grimm, 2006). IMPC data showing either lethality, lack of a specific phenotype of interest, presence of this phenotype, and/or presence of additional phenotypes can guide research decisions for individual laboratories and optimize the use of limited resources.

Web resources for obtaining ES cells, mice and phenotypic data

The Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) website (www.informatics.jax.org) is an excellent source of information on the availability of genetically modified mice. The IMPC website provides information on obtaining ES cells and cryopreserved sperm made available through the IKMC. The Monash University Embryonic Stem Cell (ES Cell)-to-Mouse Service group has published their experiences, from a ‘client’ perspective, using IKMC ES cells obtained worldwide (Cotton et al., 2015).

Information from individual IMPC phenotyping centers and the publicly available data from Deltagen and Lexicon are available in Table S1.

Note added in proof

Sotagliflozin has been approved within the European Union for use as an adjunct to insulin therapy to improve glycemic control in adults with Type 1 diabetes and a body mass index ≥27 kg/m2, who could not achieve adequate glycemic control despite optimal insulin therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Lexicon and IMPC phenotyping campaigns involved contributions of hundreds of scientists, who are imperfectly captured in publications. R.B. worked for 18 months at the German Mouse Clinic (https://www.mouseclinic.de), an IMPC phenotyping center, and had many positive interactions with IMPC scientists. Special thanks to DMM Reviews Editor Julija Hmeljak for many helpful comments.

Footnotes

Competing interests

D.R.P. is currently employed at Lexicon Pharmaceuticals and has stock shares and stock options. R.B. and P.V. were previously employed at Lexicon Pharmaceuticals. R.B. owns Lexicon stock shares. P.V. has no financial interests.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to writing and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Lexicon Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dmm.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dmm.038224.supplemental

References

- Abdollahpour H., Appaswamy G., Kotlarz D., Diestelhorst J., Beier R., Schäffer A. A., Gertz E. M., Schambach A., Kreipe H. H., Pfeifer D. et al. (2012). The phenotype of human STK4 deficiency. Blood 119, 3450-3457. 10.1182/blood-2011-09-378158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abid A., Ismail M., Mehdi S. Q. and Khaliq S. (2006). Identification of novel mutations in the SEMA4A gene associated with retinal degenerative diseases. J. Med. Genet. 43, 378-381. 10.1136/jmg.2005.035055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuin A., Hansen G. M. and Zambrowicz B. (2007). Gene trap mutagenesis. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 178, 129-147. 10.1007/978-3-540-35109-2_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ADHR Consortium (2000). Autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets is associated with mutations in FGF23. Nat. Genet. 26, 345-348. 10.1038/81664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adissu H. A., Estabel J., Sunter D., Tuck E., Hooks Y., Carragher D. M., Clarke K., Karp N. A., Sanger Mouse Genetic Project, Newbigging S. et al. (2014). Histopathology reveals correlative and unique phenotypes in a high-throughput mouse phenotyping screen. Dis. Model. Mech. 7, 515-524. 10.1242/dmm.015263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A. K., Arioglu E., De Almeida S., Akkoc N., Taylor S. I., Bowcock A. M., Barnes R. I. and Garg A. (2002). AGPAT2 is mutated in congenital generalized lipodystrophy linked to chromosome 9q34. Nat. Genet. 31, 21-23. 10.1038/ng880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shami A., Jhaver K. G., Vogel P., Wilkins C., Humphries J., Davis J. J., Xu N., Potter D. G., Gerhardt B., Mullinax R. et al. (2010a). Regulators of the proteasome pathway, Uch37 and Rpn13, play distinct roles in mouse development. PLoS ONE 5, e13654 10.1371/journal.pone.0013654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shami A., Wilkins C., Crisostomo J., Seshasayee D., Martin F., Xu N., Suwanichkul A., Anderson S. J. and Oravecz T. (2010b). The adaptor protein Sh2d3c is critical for marginal zone B cell development and function. J. Immunol. 185, 327-334. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shami A., Crisostomo J., Wilkins C., Xu N., Humphries J., Chang W. C., Anderson S. J. and Oravecz T. (2013). Integrin-α FG-GAP repeat-containing protein 2 is critical for normal B cell differentiation and controls disease development in a lupus model. J. Immunol. 191, 3789-3798. 10.4049/jimmunol.1203534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkanderi S., Molinari E., Shaheen R., Elmaghloob Y., Stephen L. A., Sammut V., Ramsbottom S. A., Srivastava S., Cairns G., Edwards N. et al. (2018). ARL3 mutations cause Joubert Syndrome by disrupting ciliary protein composition. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103, 612-620. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almomani R., Verhagen J. M. A., Herkert J. C., Brosens E., van Spaendonck-Zwarts K. Y., Asimaki A., van der Zwaag P. A., Frohn-Mulder I. M. E., Bertoli-Avella A. M., Boven L. G. et al. (2016). Biallelic truncating mutations in ALPK3 cause severe pediatric cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 515-525. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arantes H. P., Barros E. R., Kunii I., Bilezikian J. P. and Lazaretti-Castro M. (2011). Teriparatide increases bone mineral density in a man with osteoporosis pseudoglioma. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 2823-2826. 10.1002/jbmr.530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armit C. (2015). Into the blue: the importance of murine lacZ gene expression profiling in understanding and treating human disease. Dis. Model. Mech. 8, 1341-1343. 10.1242/dmm.023606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold C. N., Barnes M. J., Berger M., Blasius A. L., Brandl K., Croker B., Crozat K., Du X., Eidenschenk C., Georgel P. et al. (2012). ENU-induced phenovariance in mice: inferences from 587 mutations. BMC Res Notes. 5, 577 10.1186/1756-0500-5-577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashikov A., Abu Bakar N., Wen X.-Y., Niemeijer M., Rodrigues Pinto Osorio G., Brand-Arzamendi K., Hasadsri L., Hansikova H., Raymond K., Vicogne D. et al. (2018). Integrating glycomics and genomics uncovers SLC10A7 as essential factor for bone mineralization by regulating post-Golgi protein transport and glycosylation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 3029-3045. 10.1093/hmg/ddy213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayadi A., Birling M.-C., Bottomley J., Bussell J., Fuchs H., Fray M., Gailus-Durner V., Greenaway S., Houghton R., Karp N. et al. (2012). Mouse large-scale phenotyping initiatives: overview of the European Mouse Disease Clinic (EUMODIC) and of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Mouse Genetics Project. Mamm. Genome 23, 600-610. 10.1007/s00335-012-9418-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker K. B., Wray S. P., Ritter R., Mason S., Lanthorn T. H. and Savelieva K. V. (2010). Male and female Fmr1 knockout mice on C57 albino background exhibit spatial learning and memory impairments. Genes Brain Behav. 9, 562-574. 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00585.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balemans W., Ebeling M., Patel N., Van Hul E., Olson P., Dioszegi M., Lacza C., Wuyts W., Van Den Ende J., Willems P. et al. (2001). Increased bone density in sclerosteosis is due to the deficiency of a novel secreted protein (SOST). Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 537-543. 10.1093/hmg/10.5.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels C. F., Bükülmez H., Padayatti P., Rhee D. K., van Ravenswaaij-Arts C., Pauli R. M., Mundlos S., Chitayat D., Shih L.-Y., Al-Gazali L. I., et al. (2004). Mutations in the transmembrane natriuretic peptide receptor NPR-B impair skeletal growth and cause acromesomelic dysplasia, type Maroteaux. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75, 27-34. 10.1086/422013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett J. H. D., Gogakos A., White J. K., Evans H., Jacques R. M., van der Spek A. H., Ramirez-Solis R., Ryder E., Sunter D., Boyde A. et al. (2012). Rapid-throughput skeletal phenotyping of 100 knockout mice identifies 9 new genes that determine bone strength. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002858 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Cormier S., Lelliott C. J., Logan J. G., Lafont D. T., Merametdjian L., Leitch V. D., Butterfield N. C., Protheroe H. J., Croucher P. I., Baldock P. A. et al. (2019). Slc20a2, encoding the phosphate transporter PiT2, is an important genetic determinant of bone quality and strength. J. Bone Miner. Res. e3691 10.1002/jbmr.3691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigneux A. P., Davies B. S. J., Gin P., Weinstein M. M., Farber E., Qiao X., Peale F., Bunting S., Walzem R. L., Wong J. S. et al. (2007). Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 plays a critical role in the lipolytic processing of chylomicrons. Cell Metab. 5, 279-291. 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigneux A. P., Franssen R., Bensadoun A., Gin P., Melford K., Peter J., Walzem R. L., Weinstein M. M., Davies B. S. J., Kuivenhoven J. A. et al. (2009). Chylomicronemia with a mutant GPIHBP1 (Q115P) that cannot bind lipoprotein lipase. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 956-962. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.186577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry V., Francis P., Kaushal S., Moore A. and Bhattacharya S. (2000). Missense mutations in MIP underlie autosomal dominant ‘polymorphic’ and lamellar cataracts linked to 12q. Nat. Genet. 25, 15-17. 10.1038/75538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon A., Minai L., Serre V., Jais J.-P., Sarzi E., Aubert S., Chrétien D., de Lonlay P., Paquis-Flucklinger V., Arakawa H. et al. (2007). Mutation of RRM2B, encoding p53-controlled ribonucleotide reductase (p53R2), causes severe mitochondrial DNA depletion. Nat. Genet. 39, 776-780. 10.1038/ng2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowl M. R., Simon M. M., Ingham N. J., Greenaway S., Santos L., Cater H., Taylor S., Mason J., Kurbatova N., Pearson S. et al. (2017). A large scale hearing loss screen reveals an extensive unexplored genetic landscape for auditory dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 8, 886 10.1038/s41467-017-00595-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracco P. A., Bertoni A. P. S. and Wink M. R. (2014). NTPDase5/PCPH as a new target in highly aggressive tumors: a systematic review. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 123010 10.1155/2014/123010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley A., Anastassiadis K., Ayadi A., Battey J. F., Bell C., Birling M.-C., Bottomley J., Brown S. D., Bürger A., Bult C. J. et al. (2012). The mammalian gene function resource: the International Knockout Mouse Consortium. Mamm. Genome 23, 580-586. 10.1007/s00335-012-9422-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brommage R., Desai U., Revelli J.-P., Donoviel D. B., Fontenot G. K., Dacosta C. M., Smith D. D., Kirkpatrick L. L., Coker K. J., Donoviel M. S. et al. (2008). High-throughput screening of mouse knockout lines identifies true lean and obese phenotypes. Obesity 16, 2362-2367. 10.1038/oby.2008.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brommage R., Liu J., Hansen G. M., Kirkpatrick L. L., Potter D. G., Sands A. T., Zambrowicz B., Powell D. R. and Vogel P. (2014). High-throughput screening of mouse gene knockouts identifies established and novel skeletal phenotypes. Bone Res. 2, 14034 10.1038/boneres.2014.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brommage R., Liu J., Doree D., Yu W., Powell D. R. and Yang M. Q. (2015). Adult Tph2 knockout mice without brain serotonin have moderately elevated spine trabecular bone but moderately low cortical bone thickness. Bonekey Rep. 4, 718 10.1038/bonekey.2015.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brommage R., Liu J., Vogel P., Mseeh F., Thompson A. Y., Potter D. G., Shadoan M. K., Hansen G. M., Jeter-Jones S., Cui J. et al. (2019). NOTUM inhibition increases endocortical bone formation and bone strength. Bone Res. 7, 2 10.1038/s41413-018-0038-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. M., Drossman D. A., Wood A. J. J., Cline G. A., Frazier K. S., Jackson J. I., Bronner J., Freiman J., Zambrowicz B., Sands A. et al. (2011). The tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor LX1031 shows clinical benefit in patients with nonconstipating irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 141, 507-516. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. D. M., Holmes C. C., Mallon A.-M., Meehan T. F., Smedley D. and Wells S. (2018). High-throughput mouse phenomics for characterizing mammalian gene function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 357-370. 10.1038/s41576-018-0005-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkow M. E., Gardner J. C., Van Ness J., Paeper B. W., Kovacevich B. R., Proll S., Skonier J. E., Zhao L., Sabo P. J., Fu Y.-H. et al. (2001). Bone dysplasia sclerosteosis results from loss of the SOST gene product, a novel cystine knot-containing protein. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 577-589. 10.1086/318811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield N. C., Logan J. G., Waung J., Williams G. R. and Bassett J. H. D. (2019). Quantitative X-Ray imaging of mouse bone by Faxitron. Methods Mol. Biol. 1914, 559-569. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8997-3_30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalhoub N., Benachenhou N., Rajapurohitam V., Pata M., Ferron M., Frattini A., Villa A. and Vacher J. (2003). Grey-lethal mutation induces severe malignant autosomal recessive osteopetrosis in mouse and human. Nat. Med. 9, 399-406. 10.1038/nm842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover C. A., Boldt H. B., Bale L. K., Clifton K. B., Grell J. A., Mader J. R., Mason E. J. and Powell D. R. (2011). Pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A2 (PAPP-A2): tissue expression and biological consequences of gene knockout in mice. Endocrinology 152, 2837-2844. 10.1210/en.2011-0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D. N., Krawczak M., Polychronakos C., Tyler-Smith C. and Kehrer-Sawatzki H. (2013). Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Hum. Genet. 132, 1077-1130. 10.1007/s00439-013-1331-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma M. P., Pepe S., Annunziata I., Newbold R. F., Grompe M., Parenti G. and Ballabio A. (2003). The multiple sulfatase deficiency gene encodes an essential and limiting factor for the activity of sulfatases. Cell 113, 445-456. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00348-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton L. M., Meilak M. L., Templeton T., Gonzales J. G., Nenci A., Cooney M., Truman D., Rodda F., Lynas A., Viney E. et al. (2015). Utilising the resources of the International Knockout Mouse Consortium: the Australian experience. Mamm. Genome 26, 142-153. 10.1007/s00335-015-9555-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Niziolek P. J., MacDonald B. T., Zylstra C. R., Alenina N., Robinson D. R., Zhong Z., Matthes S., Jacobsen C. M., Conlon R. A. et al. (2011). Lrp5 functions in bone to regulate bone mass. Nat. Med. 17, 684-691. 10.1038/nm.2388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauber A., Muñoz-Calvo M. T., Barrios V., Domené H. M., Kloverpris S., Serra-Juhé C., Desikan V., Pozo J., Muzumdar R., Martos-Moreno G. Á. et al. (2016). Mutations in pregnancy-associated plasma protein A2 cause short stature due to low IGF-I availability. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 363-374. 10.15252/emmm.201506106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davisson M. T., Bergstrom D. E., Reinholdt L. G. and Donahue L. R. (2012). Discovery genetics: the history and future of spontaneous mutation research. Curr. Protoc. Mouse Biol. 2, 103-118. 10.1002/9780470942390.mo110200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Angelis M. H., Nicholson G., Selloum M., White J. K., Morgan H., Ramirez-Solis R., Sorg T., Wells S., Fuchs H., Fray M. et al. (2015). Analysis of mammalian gene function through broad-based phenotypic screens across a consortium of mouse clinics. Nat. Genet. 47, 969-978. 10.1038/ng.3360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai U., Lee E.-C., Chung K., Gao C., Gay J., Key B., Hansen G., Machajewski D., Platt K. A., Sands A. T. et al. (2007). Lipid-lowering effects of anti-angiopoietin-like 4 antibody recapitulate the lipid phenotype found in angiopoietin-like 4 knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 11766-11771. 10.1073/pnas.0705041104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey F. E., Gusarova V., Dunbar R. L., O'Dushlaine C., Schurmann C., Gottesman O., McCarthy S., Van Hout C. V., Bruse S., Dansky H. M. et al. (2017). Genetic and pharmacologic inactivation of ANGPTL3 and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 211-221. 10.1056/NEJMoa1612790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Costanzo S., Balasubramanian A., Pond H. L., Rozkalne A., Pantaleoni C., Saredi S., Gupta V. A., Sunu C. M., Yu T. W., Kang P. B. et al. (2014). POMK mutations disrupt muscle development leading to a spectrum of neuromuscular presentations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 5781-5792. 10.1093/hmg/ddu296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson M. E., Flenniken A. M., Ji X., Teboul L., Wong M. D., White J. K., Meehan T. F., Weninger W. J., Westerberg H., Adissu H. et al. (2016). High-throughput discovery of novel developmental phenotypes. Nature 537, 508-514. 10.1038/nature19356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiTommaso T., Jones L. K., Cottle D. L., Gerdin A.-K., Vancollie V. E., Watt F. M., Ramirez-Solis R., Bradley A., Steel K. P., Sundberg J. P. et al. (2014). Identification of genes important for cutaneous function revealed by a large scale reverse genetic screen in the mouse. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004705 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoviel D. B., Freed D. D., Vogel H., Potter D. G., Hawkins E., Barrish J. P., Mathur B. N., Turner C. A., Geske R., Montgomery C. A. et al. (2001). Proteinuria and perinatal lethality in mice lacking NEPH1, a novel protein with homology to NEPHRIN. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 4829-4836. 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4829-4836.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoviel M. S., Hait N. C., Ramachandran S., Maceyka M., Takabe K., Milstien S., Oravecz T. and Spiegel S. (2015). Spinster 2, a sphingosine-1-phosphate transporter, plays a critical role in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. FASEB J. 29, 5018-5028. 10.1096/fj.15-274936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubail J., Huber C., Chantepie S., Sonntag S., Tüysüz B., Mihci E., Gordon C. T., Steichen-Gersdorf E., Amiel J., Nur B. et al. (2018). SLC10A7 mutations cause a skeletal dysplasia with amelogenesis imperfecta mediated by GAG biosynthesis defects. Nat. Commun. 9, 3087 10.1038/s41467-018-05191-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyment N. A., Jiang X., Chen L., Hong S.-H., Adams D. J., Ackert-Bicknell C., Shin D.-G. and Rowe D. W. (2016). High-throughput, multi-image cryohistology of mineralized tissues. J. Vis. Exp. e54468 10.3791/54468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelbusch C., Cindrić S., Dougherty G. W., Loges N. T., Olbrich H., Rivlin J., Wallmeier J., Pennekamp P., Amirav I. and Omran H. (2017). Mutation of serine/threonine protein kinase 36 (STK36) causes primary ciliary dyskinesia with a central pair defect. Hum. Mutat. 38, 964-969. 10.1002/humu.23261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A. M., Isserlin R., Bader G. D., Frye S. V., Willson T. M. and Yu F. H. (2011). Too many roads not taken. Nature 470, 163-165. 10.1038/470163a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppig J. T. (2017). Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) Resource: genetic, genomic, and biological knowledgebase for the laboratory mouse. ILAR J. 58, 17-41. 10.1093/ilar/ilx013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairfield H., Srivastava A., Ananda G., Liu R., Kircher M., Lakshminarayana A., Harris B. S., Karst S. Y., Dionne L. A., Kane C. C. et al. (2015). Exome sequencing reveals pathogenic mutations in 91 strains of mice with Mendelian disorders. Genome Res. 25, 948-957. 10.1101/gr.186882.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng N., Young S. F., Aguilera G., Puricelli E., Adler-Wailes D. C., Sebring N. G. and Yanovski J. A. (2005). Co-occurrence of two partially inactivating polymorphisms of MC3R is associated with pediatric-onset obesity. Diabetes 54, 2663-2667. 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan C., Gaulton A., Kruger F. A., Lumbers R. T., Shah T., Engmann J., Galver L., Kelley R., Karlsson A., Santos R. et al. (2017). The druggable genome and support for target identification and validation in drug development. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaag1166 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch R. A., Donoviel D. B., Potter D., Shi M., Fan A., Freed D. D., Wang C. Y., Zambrowicz B. P., Ramirez-Solis R., Sands A. T. et al. (2002). Mdmx is a negative regulator of p53 activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 62, 3221-3225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannick J., Thorleifsson G., Beer N. L., Jacobs S. B. R., Grarup N., Burtt N. P., Mahajan A., Fuchsberger C., Atzmon G., Benediktsson R. et al. (2014). Loss-of-function mutations in SLC30A8 protect against type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 46, 357-363. 10.1038/ng.2915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis P., Chung J.-J., Yasui M., Berry V., Moore A., Wyatt M. K., Wistow G., Bhattacharya S. S. and Agre P. (2000). Functional impairment of lens aquaporin in two families with dominantly inherited cataracts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2329-2334. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.hmg.a018925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frattini A., Pangrazio A., Susani L., Sobacchi C., Mirolo M., Abinun M., Andolina M., Flanagan A., Horwitz E. M., Mihci E. et al. (2003). Chloride channel ClCN7 mutations are responsible for severe recessive, dominant, and intermediate osteopetrosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 1740-1747. 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.10.1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenthal B., Logan J., Sanger Institute Mouse Pipelines, Croucher P. I., Williams G. R. and Bassett J. H. D. (2016). Rapid phenotyping of knockout mice to identify genetic determinants of bone strength. J. Endocrinol. 231, R31-R46. 10.1530/JOE-16-0258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galada C., Shah H., Shukla A. and Girisha K. M. (2017). A novel sequence variant in SFRP4 causing Pyle disease. J. Hum. Genet. 62, 575-576. 10.1038/jhg.2016.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandotra S., Le Dour C., Bottomley W., Cervera P., Giral P., Reznik Y., Charpentier G., Auclair M., Delépine M., Barroso I. et al. (2011). Perilipin deficiency and autosomal dominant partial lipodystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 740-748. 10.1056/NEJMoa1007487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg S. K., Henry R. R., Banks P., Buse J. B., Davies M. J., Fulcher G. R., Pozzilli P., Gesty-Palmer D., Lapuerta P., Simó R. et al. (2017). Effects of Sotagliflozin added to Insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2337-2348. 10.1056/NEJMoa1708337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfman C. M., Vogel P., Issa T. M., Turner C. A., Lee W.-S., Kornfeld S. and Rice D. S. (2007). Mice lacking alpha/beta subunits of GlcNAc-1-phosphotransferase exhibit growth retardation, retinal degeneration, and secretory cell lesions. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 5221-5228. 10.1167/iovs.07-0452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giunta C., Elçioglu N. H., Albrecht B., Eich G., Chambaz C., Janecke A. R., Yeowell H., Weis M. A., Eyre D. R., Kraenzlin M. et al. (2008). Spondylocheiro dysplastic form of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome--an autosomal-recessive entity caused by mutations in the zinc transporter gene SLC39A13. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82, 1290-1305. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y., Slee R. B., Fukai N., Rawadi G., Roman-Roman S., Reginato A. M., Wang H., Cundy T., Glorieux F. H., Lev D. et al. (2001). LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell. 107, 513-523. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00571-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin N. C., Ding Z.-M., Harrison B. A., Strobel E. D., Harris A. L., Smith M., Thompson A. Y., Xiong W., Mseeh F., Bruce D. J. et al. (2017). Discovery of LX2761, a sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1) inhibitor restricted to the intestinal lumen, for the treatment of diabetes. J. Med. Chem. 60, 710-721. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D. (2006). Mouse genetics. A mouse for every gene. Science 312, 1862-1866. 10.1126/science.312.5782.1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Girisha K. M., Iida A., Hebbar M., Shukla A., Shah H., Nishimura G., Matsumoto N., Nismath S., Miyake N. et al. (2017). Identification of a novel LRRK1 mutation in a family with osteosclerotic metaphyseal dysplasia. J. Hum. Genet. 62, 437-441. 10.1038/jhg.2016.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris D. P., Vogel P., Wims M., Moberg K., Humphries J., Jhaver K. G., DaCosta C. M., Shadoan M. K., Xu N., Hansen G. M. et al. (2011). Requirement for class II phosphoinositide 3-kinase C2alpha in maintenance of glomerular structure and function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 63-80. 10.1128/MCB.00468-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C.-L., Lin W., Seshasayee D., Chen Y.-H., Ding X., Lin Z., Suto E., Huang Z., Lee W. P., Park H. et al. (2012). Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 3 deficiency perturbs lysosome function and macrophage homeostasis. Science 335, 89-92. 10.1126/science.1213682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa S., Imel E. A., Kreiter M. L., Yu X., Mackenzie D. S., Sorenson A. H., Goetz R., Mohammadi M., White K. E. and Econs M. J. (2007). A homozygous missense mutation in human KLOTHO causes severe tumoral calcinosis. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2684-2691. 10.1172/JCI31330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida A., Xing W., Docx M. K. F., Nakashima T., Wang Z., Kimizuka M., Van Hul W., Rating D., Spranger J., Ohashi H. et al. (2016). Identification of biallelic LRRK1 mutations in osteosclerotic metaphyseal dysplasia and evidence for locus heterogeneity. J. Med. Genet. 53, 568-574. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K., Matsuda K., Itoh M., Kawaguchi H., Tomoike H., Aoyagi T., Nagai R., Hori M., Nakamura Y. and Tanaka T. (2002). Osteopenia and male-specific sudden cardiac death in mice lacking a zinc transporter gene, Znt5. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 1775-1784. 10.1093/hmg/11.15.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniec U. T., Wronski T. J., Liu J., Rivera M. F., Arzaga R. R., Hansen G. and Brommage R. (2007). PTH stimulates bone formation in mice deficient in Lrp5. J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 394-402. 10.1359/jbmr.061118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janecke A. R., Xu R., Steichen-Gersdorf E., Waldegger S., Entenmann A., Giner T., Krainer I., Huber L. A., Hess M. W., Frishberg Y. et al. (2017). Deficiency of the sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase SGPL1 is associated with congenital nephrotic syndrome and congenital adrenal calcifications. Hum. Mutat. 38, 365-372. 10.1002/humu.23192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaureguiberry G., De la Dure-Molla M., Parry D., Quentric M., Himmerkus N., Koike T., Poulter J., Klootwijk E., Robinette S. L., Howie A. J. et al. (2012). Nephrocalcinosis (enamel renal syndrome) caused by autosomal recessive FAM20A mutations. Nephron Physiol. 122, 1-6. 10.1159/000349989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski K., Jankowski P. and Kosior D. A. (2017). PCSK9 inhibitors - from discovery of a single mutation to a groundbreaking therapy of lipid disorders in one decade. Arch. Med. Sci. 13, 914-929. 10.5114/aoms.2017.65239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen A., Rosti R. O., Musaev D., Sticca E., Harripaul R., Zaki M., Çağlayan A. O., Azam M., Sultan T., Froukh T. et al. (2016). Mutations in MBOAT7, encoding lysophosphatidylinositol acyltransferase I, lead to intellectual disability accompanied by epilepsy and autistic features. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 912-916. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge H. J., Yang S., Burton J. B., Paes K., Shu X., French D. M., Costa M., Rice D. S. and Ye W. (2009). TSPAN12 regulates retinal vascular development by promoting Norrin- but not Wnt-induced FZD4/beta-catenin signaling. Cell 139, 299-311. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice M. J. and Dhillon P. (2016). Using the mouse to model human disease: increasing validity and reproducibility. Dis. Model. Mech. 9, 101-103. 10.1242/dmm.024547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantaputra P. N., Kaewgahya M., Hatsadaloi A., Vogel P., Kawasaki K., Ohazama A. and Ketudat Cairns J. R. (2015). GREMLIN 2 mutations and dental anomalies. J. Dent. Res. 94, 1646-1652. 10.1177/0022034515608168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp N. A., Baker L. A., Gerdin A.-K. B., Adams N. C., Ramírez-Solis R. and White J. K. (2010). Optimising experimental design for high-throughput phenotyping in mice: a case study. Mamm. Genome 21, 467-476. 10.1007/s00335-010-9279-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp J. P., Morris J. A., Medina-Gomez C., Forgetta V., Warrington N. M., Youlten S. E., Zheng J., Gregson C. L., Grundberg E., Trajanoska K. et al. (2017). Identification of 153 new loci associated with heel bone mineral density and functional involvement of GPC6 in osteoporosis. Nat. Genet. 49, 1468-1475. 10.1038/ng.3949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiper P. O. S., Saito H., Gori F., Unger S., Hesse E., Yamana K., Kiviranta R., Solban N., Liu J., Brommage R. et al. (2016). Cortical-bone fragility - insights from sFRP4 deficiency in Pyle's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 2553-2562. 10.1056/NEJMoa1509342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollberg G., Darin N., Benan K., Moslemi A.-R., Lindal S., Tulinius M., Oldfors A. and Holme E. (2009). A novel homozygous RRM2B missense mutation in association with severe mtDNA depletion. Neuromuscul. Disord. 19, 147-150. 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koscielny G., Yaikhom G., Iyer V., Meehan T. F., Morgan H., Atienza-Herrero J., Blake A., Chen C.-K., Easty R., Di Fenza A. et al. (2014). The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium Web Portal, a unified point of access for knockout mice and related phenotyping data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D802-D809. 10.1093/nar/gkt977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostich W., Hamman B. D., Li Y.-W., Naidu S., Dandapani K., Feng J., Easton A., Bourin C., Baker K., Allen J. et al. (2016). Inhibition of AAK1 kinase as a novel therapeutic approach to treat neuropathic pain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 358, 371-386. 10.1124/jpet.116.235333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz T. M., Harroch S., Manor O., Lichtenberg P., Friedlander Y., Seandel M., Harkavy-Friedman J., Walsh-Messinger J., Dolgalev I., Heguy A. et al. (2015). De novo mutations from sporadic schizophrenia cases highlight important signaling genes in an independent sample. Schizophr. Res. 166, 119-124. 10.1016/j.schres.2015.05.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz T. M., Berns A., Shields J., Rothman K., Walsh-Messinger J., Goetz R. R., Chao M. V. and Malaspina D. (2016). Phenotypically distinct subtypes of psychosis accompany novel or rare variants in four different signaling genes. EBioMedicine 6, 206-214. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke M. H., Hörsch D., Caplin M. E., Anthony L. B., Bergsland E., Öberg K., Welin S., Warner R. R. P., Lombard-Bohas C., Kunz P. L. et al. (2017). Telotristat Ethyl, a tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor for the treatment of carcinoid syndrome. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 14-23. 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar L., Michalczyk A., McKay J., Ford D., Kambe T., Hudek L., Varigios G., Taylor P. E. and Ackland M. L. (2015). Altered expression of two zinc transporters, SLC30A5 and SLC30A6, underlies a mammary gland disorder of reduced zinc secretion into milk. Genes Nutr. 10, 487 10.1007/s12263-015-0487-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang B., Pu J., Hunter I., Liu M., Martin-Granados C., Reilly T. J., Gao G.-D., Guan Z.-L., Li W.-D., Shi Y.-Y. et al. (2014). Recurrent deletions of ULK4 in schizophrenia: a gene crucial for neuritogenesis and neuronal motility. J. Cell Sci. 127, 630-640. 10.1242/jcs.137604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-S., Poh L. K.-S. and Loke K.-Y. (2002). A novel melanocortin 3 receptor gene (MC3R) mutation associated with severe obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 1423-1426. 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.-C., Desai U., Gololobov G., Hong S., Feng X., Yu X.-C., Gay J., Wilganowski N., Gao C., Du L.-L. et al. (2009). Identification of a new functional domain in angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3) and angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) involved in binding and inhibition of lipoprotein lipase (LPL). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13735-13745. 10.1074/jbc.M807899200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Laue K., Temtamy S., Aglan M., Kotan L. D., Yigit G., Canan H., Pawlik B., Nürnberg G., Wakeling E. L. et al. (2010). Temtamy preaxial brachydactyly syndrome is caused by loss-of-function mutations in chondroitin synthase 1, a potential target of BMP signaling. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87, 757-767. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liakath-Ali K., Vancollie V. E., Heath E., Smedley D. P., Estabel J., Sunter D., Ditommaso T., White J. K., Ramirez-Solis R., Smyth I. et al. (2014). Novel skin phenotypes revealed by a genome-wide mouse reverse genetic screen. Nat. Commun. 5, 3540 10.1038/ncomms4540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares G. R., Brommage R., Powell D. R., Xing W., Chen S.-T., Alshbool F. Z., Lau K.-H. W., Wergedal J. E. and Mohan S. (2012). Claudin 18 is a novel negative regulator of bone resorption and osteoclast differentiation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1553-1565. 10.1002/jbmr.1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd K. C. K., Meehan T., Beaudet A., Murray S., Svenson K., McKerlie C., West D., Morse I., Parkinson H., Brown S. et al. (2015). Precision medicine: look to the mice. Science 349, 390 10.1126/science.349.6246.390-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorès P., Coutton C., El Khouri E., Stouvenel L., Givelet M., Thomas L., Rode B., Schmitt A., Louis B., Sakheli Z. et al. (2018). Homozygous missense mutation L673P in adenylate kinase 7 (AK7) leads to primary male infertility and multiple morphological anomalies of the flagella but not to primary ciliary dyskinesia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 1196-1211. 10.1093/hmg/ddy034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovric S., Goncalves S., Gee H. Y., Oskouian B., Srinivas H., Choi W.-I., Shril S., Ashraf S., Tan W., Rao J. et al. (2017). Mutations in sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase cause nephrosis with ichthyosis and adrenal insufficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 912-928. 10.1172/JCI89626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur D. (2012). Methods: face up to false positives. Nature 487, 427-428. 10.1038/487427a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy C. M. and Notario V. (2013). The ENTPD5/mt-PCPH oncoprotein is a catalytically inactive member of the ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase family. Int. J. Oncol. 43, 1244-1252. 10.3892/ijo.2013.2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maussion G., Cruceanu C., Rosenfeld J. A., Bell S. C., Jollant F., Szatkiewicz J., Collins R. L., Hanscom C., Kolobova I., de Champfleur N. M. et al. (2017). Implication of LRRC4C and DPP6 in neurodevelopmental disorders. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 173, 395-406. 10.1002/ajmg.a.38021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Gomez C., Kemp J. P., Estrada K., Eriksson J., Liu J., Reppe S., Evans D. M., Heppe D. H. M., Vandenput L., Herrera L. et al. (2012). Meta-analysis of genome-wide scans for total body BMD in children and adults reveals allelic heterogeneity and age-specific effects at the WNT16 locus. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002718 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan T. F., Conte N., West D. B., Jacobsen J. O., Mason J., Warren J., Chen C.-K., Tudose I., Relac M., Matthews P. et al. (2017). Disease model discovery from 3,328 gene knockouts by The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium. Nat. Genet. 49, 1231-1238. 10.1038/ng.3901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata H., Castaneda J. M., Fujihara Y., Yu Z., Archambeault D. R., Isotani A., Kiyozumi D., Kriseman M. L., Mashiko D., Matsumura T. et al. (2016). Genome engineering uncovers 54 evolutionarily conserved and testis-enriched genes that are not required for male fertility in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 7704-7710. 10.1073/pnas.1608458113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. W. (2005). High-throughput gene knockouts and phenotyping in mice. Ernst Schering Res. Found. Workshop 50, 27-44. 10.1007/3-540-26811-1_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B. A., Roux M. J., Sebbag L., Cooper A., Edwards S. G., Leonard B. C., Imai D. M., Griffey S., Bower L., Clary D. et al. (2018a). A population study of common ocular abnormalities in C57BL/6N rd8 mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 2252-2261. 10.1167/iovs.17-23513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B. A., Leonard B. C., Sebbag L., Edwards S. G., Cooper A., Imai D. M., Straiton E., Santos L., Reilly C., Griffey S. M. et al. (2018b). Identification of genes required for eye development by high-throughput screening of mouse knockouts. Commun. Biol. 1, 236 10.1038/s42003-018-0226-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello R., Bertin T. K., Chen Y., Hicks J., Tonachini L., Monticone M., Castagnola P., Rauch F., Glorieux F. H., Vranka J. et al. (2006). CRTAP is required for prolyl 3- hydroxylation and mutations cause recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Cell 127, 291-304. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan N. V., Morris M. R., Cangul H., Gleeson D., Straatman-Iwanowska A., Davies N., Keenan S., Pasha S., Rahman F., Gentle D. et al. (2010). Mutations in SLC29A3, encoding an equilibrative nucleoside transporter ENT3, cause a familial histiocytosis syndrome (Faisalabad histiocytosis) and familial Rosai-Dorfman disease. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000833 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. A., Kemp J. P., Youlten S. E., Laurent L., Logan J. G., Chai R. C., Vulpescu N. A., Forgetta V., Kleinman A., Mohanty S. T. et al. (2019). An atlas of genetic influences on osteoporosis in humans and mice. Nat. Genet. 51, 258-266. 10.1038/s41588-018-0302-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau J. H. and Auwerx J. (2019). The virtuous cycle of human genetics and mouse models in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 255-272. 10.1038/s41573-018-0009-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehme N. T., Schmid J. P., Debeurme F., André-Schmutz I., Lim A., Nitschke P., Rieux-Laucat F., Lutz P., Picard C., Mahlaoui N. et al. (2012). MST1 mutations in autosomal recessive primary immunodeficiency characterized by defective naive T-cell survival. Blood 119, 3458-3468. 10.1182/blood-2011-09-378364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M. R., Tipney H., Painter J. L., Shen J., Nicoletti P., Shen Y., Floratos A., Sham P. C., Li M. J., Wang J. et al. (2015). The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nat. Genet. 47, 856-860. 10.1038/ng.3314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikopoulos K., Gilissen C., Hoischen A., van Nouhuys C. E., Boonstra F. N., Blokland E. A. W., Arts P., Wieskamp N., Strom T. M., Ayuso C. et al. (2010). Next-generation sequencing of a 40 Mb linkage interval reveals TSPAN12 mutations in patients with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86, 240-247. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson K., Movérare-Skrtic S., Henning P., Funck-Brentano T., Nethander M., Rivadeneira F., Koskela A., Tuukkanen J., Tuckermann J., Perret C. et al. (2018). Osteoblast-derived NOTUM reduces cortical bone mass in mice and the NOTUM locus is associated with bone mineral density in humans. J. Bone Miner. Res. 32 Suppl. 1 Available at: http://www.asbmr.org/education/AbstractDetail?aid=addeafd3-36ee-4813-bc0f-fc8701deb7de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nota B., Struys E. A., Pop A., Jansen E. E., Fernandez Ojeda M. R., Kanhai W. A., Kranendijk M., van Dooren S. J., Bevova M. R. et al. (2013). Deficiency in SLC25A1, encoding the mitochondrial citrate carrier, causes combined D-2- and L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 627-631. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprea T. I., Bologa C. G., Brunak S., Campbell A., Gan G. N., Gaulton A., Gomez S. M., Guha R., Hersey A., Holmes J. et al. (2018). Unexplored therapeutic opportunities in the human genome. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 377 10.1038/nrd.2018.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr S. L., Le D., Long J. M., Sobieszczuk P., Ma B., Tian H., Fang X., Paulson J. C., Marth J. D. and Varki N. (2013). A phenotype survey of 36 mutant mouse strains with gene-targeted defects in glycosyltransferases or glycan-binding proteins. Glycobiology 23, 363-380. 10.1093/glycob/cws150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paes K. T., Wang E., Henze K., Vogel P., Read R., Suwanichkul A., Kirkpatrick L. L., Potter D., Newhouse M. M. and Rice D. S. (2011). Frizzled 4 is required for retinal angiogenesis and maintenance of the blood-retina barrier. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 6452-6461. 10.1167/iovs.10-7146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer K., Fairfield H., Borgeia S., Curtain M., Hassan M. G., Dionne L., Yong Karst S., Coombs H., Bronson R. T., Reinholdt L. G. et al. (2016). Discovery and characterization of spontaneous mouse models of craniofacial dysmorphology. Dev. Biol. 415, 216-227. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A. K., Lu L., Wang X., Homayouni R. and Williams R. W. (2014). Functionally enigmatic genes: a case study of the brain ignorome. PLoS ONE 9, e88889 10.1371/journal.pone.0088889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce L. R., Atanassova N., Banton M. C., Bottomley B., van der Klaauw A. A., Revelli J.-P., Hendricks A., Keogh J. M., Henning E., Doree D. et al. (2013). KSR2 mutations are associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and impaired cellular fuel oxidation. Cell 155, 765-777. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman R. L. (2016). Mouse models of human disease: an evolutionary perspective. Evol. Med. Public Health 2016, 170-176. 10.1093/emph/eow014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan D. G., Anderson D. J., Howden S. E., Wong R. C. B., Hickey P. F., Pope K., Wilson G. R., Pébay A., Davis A. M., Petrou S. et al. (2016). ALPK3-deficient cardiomyocytes generated from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells and mutant human embryonic stem cells display abnormal calcium handling and establish that ALPK3 deficiency underlies familial cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 37, 2586-2590. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plenge R. M., Scolnick E. M. and Altshuler D. (2013). Validating therapeutic targets through human genetics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 581-594. 10.1038/nrd4051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plewczynski D. and Rychlewski L. (2009). Meta-basic estimates the size of druggable human genome. J. Mol. Model. 15, 695-699. 10.1007/s00894-008-0353-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter P. K., Bowl M. R., Jeyarajan P., Wisby L., Blease A., Goldsworthy M. E., Simon M. M., Greenaway S., Michel V., Barnard A. et al. (2016). Novel gene function revealed by mouse mutagenesis screens for models of age-related disease. Nat. Commun. 7, 12444 10.1038/ncomms12444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulter J. A., Ali M., Gilmour D. F., Rice A., Kondo H., Hayashi K., Mackey D. A., Kearns L. S., Ruddle J. B., Craig J. E, et al. (2010). Mutations in TSPAN12 cause autosomal-dominant familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86, 248-253. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell D. R., Desai U., Sparks M. J., Hansen G., Gay J., Schrick J., Shi Z.-Z., Hicks J. and Vogel P. (2005). Rapid development of glomerular injury and renal failure in mice lacking p53R2. Pediatr. Nephrol. 20, 432-440. 10.1007/s00467-004-1696-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell D. R., DaCosta C. M., Gay J., Ding Z.-M., Smith M., Greer J., Doree D., Jeter-Jones S., Mseeh F., Rodriguez L. A. et al. (2013). Improved glycemic control in mice lacking Sglt1 and Sglt2. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 304, E117-E130. 10.1152/ajpendo.00439.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell D. R., Gay J. P., Wilganowski N., Doree D., Savelieva K. V., Lanthorn T. H., Read R., Vogel P., Hansen G. M., Brommage R. et al. (2015). Diacylglycerol lipase α knockout mice demonstrate metabolic and behavioral phenotypes similar to those of cannabinoid receptor 1 knockout mice. Front. Endocrinol. 6, 86 10.3389/fendo.2015.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell D. R., Gay J. P., Smith M., Wilganowski N., Harris A., Holland A., Reyes M., Kirkham L., Kirkpatrick L. L., Zambrowicz B. et al. (2016). Fatty acid desaturase 1 knockout mice are lean with improved glycemic control and decreased development of atheromatous plaque. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 9, 185-199. 10.2147/DMSO.S106653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad R., Hadjidemetriou I., Maharaj A., Meimaridou E., Buonocore F., Saleem M., Hurcombe J., Bierzynska A., Barbagelata E., Bergadá I. et al. (2017). Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase mutations cause primary adrenal insufficiency and steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 942-953. 10.1172/JCI90171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probert F., Rice P., Scudamore C. L., Wells S., Williams R., Hough T. A. and Cox I. J. (2015). 1H NMR metabolic profiling of plasma reveals additional phenotypes in knockout mouse models. J. Proteome Res. 14, 2036-2045. 10.1021/pr501039k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst F. J. and Justice M. J. (2010). Mouse mutagenesis with the chemical supermutagen ENU. Methods Enzymol. 477, 297-312. 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)77015-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu A., Jansen M., Sakaris A., Min S. H., Chattopadhyay S., Tsai E., Sandoval C., Zhao R., Akabas M. H. and Goldman I. D. (2006). Identification of an intestinal folate transporter and the molecular basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. Cell 127, 917-928. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]