INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer (LC) is the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide. Despite advances in the treatment strategy, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy, 5-year survival is estimated as 9% to 20%.1,2 During the past decade, LC incidence has been increasing and age at the time of diagnosis continues to decrease.3,4 Median age at diagnosis is 70 years, and approximately 13% of all patients with LC are younger than age 50 years. Numerous studies have suggested that LC in young patients constitutes an entity with unique characteristics, such as a higher percentage of female patients, a lower rate of smoking history, a higher percentage of family history of LC, a higher rate of adenocarcinoma histology, and more advanced stage at diagnosis.5-13 However, it is still controversial whether youthful patients with LC have better or worse outcomes.14-16 In addition, most of the literature regarding young patients is associated with Asian cohorts, whereas less data about white communities are available.

Currently, a considerable percentage of patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) benefit from personalized therapy protocols that are based on the genomic profile of tumors.17,18 Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) genes affect the prognosis of patients. Recent studies have shown that young patients with NSCLC harbor more driver mutations than older patients. The rate of mutations documented in the young white population varies between articles and is approximately 20% to 30% for EGFR mutation and 10% to 20% for ALK rearrangement.17-19

There are conflicting data on whether younger patients with NSCLC achieve better or worse outcomes compared with the older population, yet most studies show that younger patients have better survival rates.7-10 Identifying the clinicopathologic characteristics and making appropriate proactive molecular profiling of the youthful population can guide treatment strategy in the clinical setting. Therefore, in the current study, we carried out a comprehensive analysis of patient clinicopathologic features and clinical outcomes in both young (age ≤ 50 years) and older (age > 60 years) patients with NSCLC.

METHODS

Patients

Patients who were diagnosed and treated for LC in the Davidoff Cancer Center, Rabin Medical Center, Israel, were identified retrospectively between January 2010 and December 2015. Patients were sorted by age at diagnosis and divided into two groups: younger than age 50 years and older than age 60 years. Patients younger than age 50 years were used in previous studies.5,8,14 As we intended to have clear discrimination from the older group, we included patients older than age 60 years. For every young patient, two older patients were enrolled (n = 62 and n = 124, respectively). Diagnosis was based on tumor pathology via surgical or biopsy specimen, or cytology examination via lung, lymph node aspiration, or pleural effusion. Exclusion criteria included patients with lung cancer other than NSCLC and those with non–pathologic-based diagnosis, or cases in which LC was combined with another type of malignancy. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Rabin Medical Center (approval no. 0391-14 RMC).

Data Collection

Medical records were reviewed retrospectively. Patient demographics, smoking history, personal and family history of cancer, medical history, body mass index at diagnosis, performance status, initial clinical presentation, time since presentation to tissue diagnosis, disease stage, histologic subtype, driving mutations, treatment, and survival data were recorded.

EGFR mutation status was analyzed using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), narrow-spectrum next-generation sequencing (NGS), or broad, hybrid capture–based NGS assays. ALK rearrangements were assessed using immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were observed until January 2017 or until the date of their death. We compared categorical characteristics using the χ2 test. Continuous variables were compared using an independent t test. Median survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Mayer method with log-rank. A P value less than .05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed using SAS (SAS/STAT User’s Guide, Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics

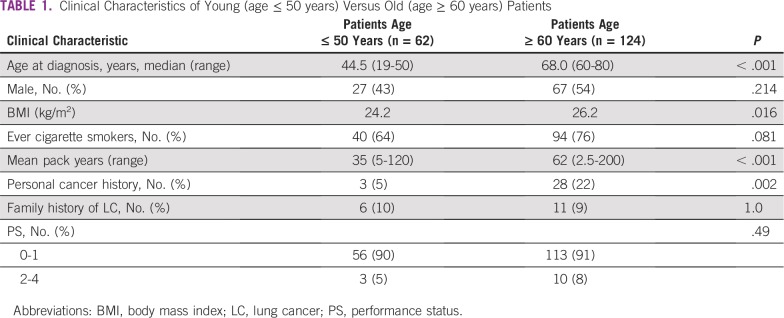

Between January 2010 and December 2015, 95 patients were diagnosed with LC at younger than age 50 years, accounting for 7.7% of all newly diagnosed patients. Sixty-two patients were included in the analysis (median age, 44.5 years). One hundred twenty-four patients age 60 years or older (median age, 68.0 years) were analyzed and compared with the younger cohort. Clinical characteristics of these patients are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Young (age ≤ 50 years) Versus Old (age ≥ 60 years) Patients

Gender distribution showed a slight predominance of female patients in the younger cohort (56% v 46% in the older group). A decreased ratio of ever-smokers in the young cohort was demonstrated (64% v 76%, respectively; P = .081), with a significantly lower median number of pack years (35 years v 62 years; P < .001). The younger cohort had lower rates of personal cancer history (5% v 22%, respectively; P < .001), with no cancer type predominance, and similar rates of family history of LC. Performance status at diagnosis was demonstrated to be similar between both cohorts. As expected, the older cohort had more comorbidities at the time of diagnosis, mostly cardiovascular disease. These patients also suffered from more lung diseases compared with the younger cohort (12% v 28%, respectively; P = .02), mostly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Course of Disease

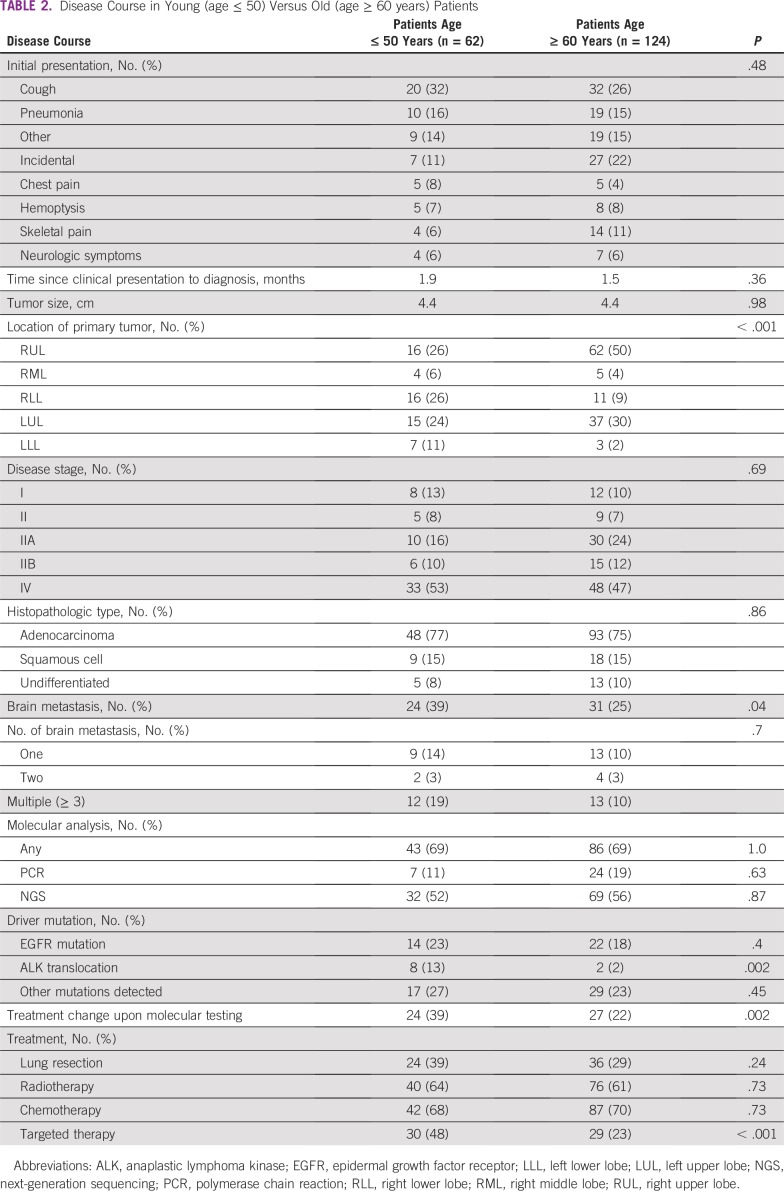

Disease presentation did not differ between the two age groups. Both cohorts demonstrated similar average time since clinical presentation to diagnosis (1.99 months v 1.53 months, respectively; not significant [NS]), and stage at diagnosis was similar in both groups (stage IV: 53.2% v 46.7%, respectively; NS). Initial tumor size was similar (4.43 cm v 4.44 cm, respectively; NS).

The majority of patients in the older cohort had the initial tumor mass located in the upper lobes of the lungs (50% in the right upper lobe and 29% in the left upper lobe) in comparison with the younger cohort which had more diversity in initial tumor location (24% left upper lobe, 25% right upper lobe, 25% right lower lobe; P < .001).

Adenocarcinoma was the most common histopathology in both age groups (77% v 75%, respectively), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (14% v 14%, respectively; Table 2). A significantly greater percentage of younger patients developed brain metastases during their disease course (39% v 25%, respectively; P = .04). In both groups, approximately 67% of patients with brain metastases developed the brain metastasis later in the disease course. In the younger age group, 39% of patients had one and 52% had multiple—more than two—brain metastases. Similar percentages were observed in the older age group: 43% had one brain metastasis and 43% had multiple brain metastases.

TABLE 2.

Disease Course in Young (age ≤ 50) Versus Old (age ≥ 60 years) Patients

Analyzing only patients who harbored an EGFR mutation, we found that young EGFR-positive patients were more likely to develop brain metastases during their disease course than older patients (71% v 36%, respectively; P < .001).

Treatment Modalities and Survival Rates

Molecular profiling was performed in 69% of patients in both age groups. A similar percentage of patients underwent PCR and NGS evaluation in both groups (approximately 15% and 53%, respectively). Sixty-four percent of patients had molecular testing performed around the time of diagnosis in both groups and 26% underwent analysis after disease progression. Additional testing after negative PCR results was performed more frequently in the younger cohort (34% v 24%, respectively; P = .16), and molecular testing affected treatment decisions more for younger patients (39% v 22%, respectively; P = .002).

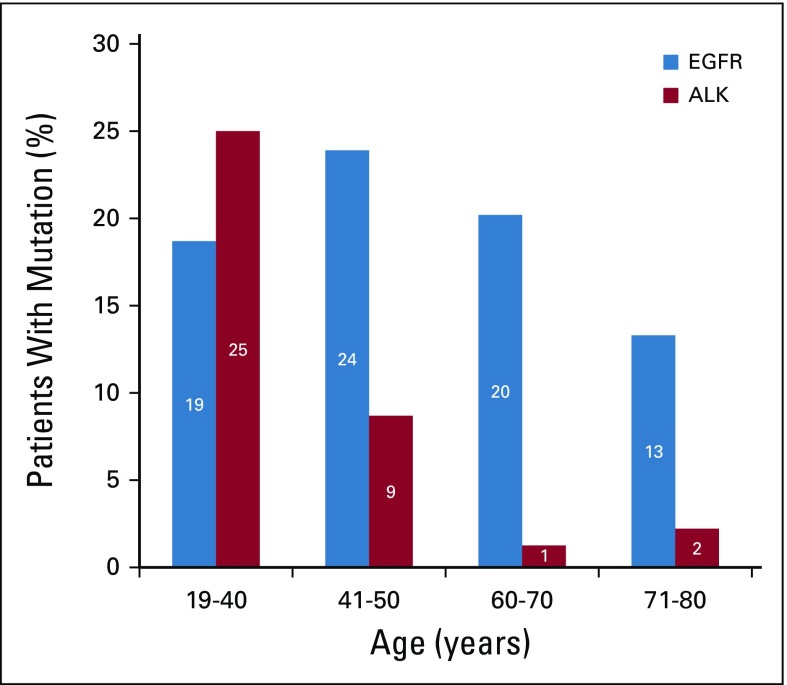

Younger patients were more likely to harbor driver mutations—EGFR mutations were more common in the younger cohort (23% v 18%, respectively; P = .4), as well as ALK translocations (13% v 2%, respectively; P = .002) as shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Additional mutations, such as c-MET, KRAS, HER2, TP53, MYC, BRAF, BRCA1, BRCA2, CTNNB1, ERBB2, APC, and others, were found in similar percentages in both patient groups upon molecular testing (27% v 23%; P = .4)

FIG 1.

Percentage of patients with driver mutations in different age groups (age < 40, 41-50, 61-70, and 71-80 years). One hundred eighty-six patients were divided into four age groups. Age group 19-40 years included 16 patients, of which three (19%) had an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation and four (25%) had anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement. Age group 41-50 years included 46 patients, of which 11 (24%) had an EGFR mutation and four (19%) had ALK rearrangement. Twenty percent patients had EGFR mutation in the age group 60-70 years, which included 79 patients, but only 1% had ALK rearrangement. The percentage of EGFR mutation was reduced to 13% in the age group 71-80 years, which included 45 patients, with 2% ALK rearrangement found

Treatment modalities were fairly similar in both cohorts, including the rate of patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy and patients who received radiotherapy. The younger cohort had a higher rate of lung resection (39% v 29%, respectively; P = .2) and a higher rate of treatment with targeted therapy (48% v 23%, respectively; P < .001) as indicated in Table 2.

Approximately 85% of patients with advanced stage disease in both cohorts received first-line treatment and 49% received second-line treatment. Of treatment-naïve patients, 15% did not receive treatment because of late-stage presentation and low performance status. Younger patients received more targeted therapy—both lines—compared with patients in the older cohort (first line: 41% v 19%, respectively; P = .01; second line: 56% v 28%, respectively; P = .02). Similar percentages of patients received chemotherapy in both lines. Of younger and older patients, 14% and 20%, respectively, ever received immunotherapy in the course of their treatment. Older patients had a higher rate of dose reduction throughout the course of their treatment (12% v 37%, respectively; P < .01).

Median survival of patients age 50 years or younger was longer than median survival of patients older than age 60 years (34 v 21 months, respectively; P = .1), but was not significant. Substratification of patients into smaller age groups demonstrated that the youngest patients (age < 40 years) had the highest median survival (59 months; Fig 2).

FIG 2.

Survival comparison of older versus younger patients in different patient groups: (A) Kaplan-Meier curve of all patients divided into two age groups: 62 patients younger than age 40 years (n = 28 censored) and 124 patients older than age 60 years (n = 44 censored). Median survival for the younger group was 34 months and 21.2 months for the older group. P = .19. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of all patients divided into four age groups: 16 patients younger than age 40 years (n = 9 censored), 46 patients age 41-50 years (n = 19 censored), 82 patients age 60-69 years (n = 32 censored), and 42 patients older than age 70 years (n = 12 censored). Median survival for the youngest group was 59.6 months, 26.1 months for those age 41- 50 years, 25 months for those age 60-69 years, and 17.2 months for the oldest age group. Significance: P = .2. Kaplan-Meier curves of driver mutation–positive patients: (C) Kaplan-Meier curve of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation–positive patients: 14 patients were younger than age 50 years (n = 6 censored) and 22 patients were older than age 60 years (n = 8 censored). Median survival was 33.5 months for younger patients and 22.8 months for older patients. Significance: P = .61. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement–positive patients: eight patients were younger than age 50 years (n = 3 censored) and two patients were older than age 60 years (n = 0 censored). Median survival was 35.5 months for younger patients and 14.4 months for older patients. Significance: P = .3. (E) Patients who developed brain metastases: 24 patients were younger than age 50 years (n = 7 censored) and 31 patients were older than age 60 years (n = 4 censored). Median survival was 24.6 months for younger patients and 18 months for older patients. Significance: P = .4. (F) Patients who did not developed brain metastases: 36 patients were younger than age 50 years (n = 20 censored) and 93 patients were older than age 60 years (n = 40 censored). Median survival was 58.8 months for younger patients and 21.6 months for older patients. Significance: P = 0.

Among patients with a driver mutation, younger patients had better median survival, but this was not statistically significant (33 v 25 months; P = .4).

Among patients who developed brain metastases, patients in the younger age cohort had better survival (24.5 v 18 months; P = .4). Furthermore, in those with no brain metastases, younger patients also had better survival, but the difference was much greater (59 v 21.6 months; P = .18).

DISCUSSION

The current study strengthens the need for defining young patients with LC as a subentity. Our retrospective study confirms the results of previous studies7,10,18-22 that indicate that younger patients have a higher rate of driver mutations and may have better prognosis. Here, we report a higher incidence of brain metastasis among young patients and, more commonly, among mutation-bearing patients. This may suggest the need to search for both molecular targets and brain metastases early in the course of disease. Deeper investigation may lead to a more tailored treatment and a better outcome for patients, and is especially important in the younger population.

In the eastern population, EGFR mutations are more common in nonsmoking women.5-13 Our cohort, which was comprised of white patients, demonstrated that younger patients harbored more targetable driver mutations compared with older patients (34% v 18%; P = .01), including a higher rate of EGFR and ALK gene alterations. The difference in prevalence of targetable mutations was much more prominent for ALK translocations, as they were prominent in the young (13%) and almost not found in the old (2%). Sacher et al,21 in 2016, demonstrated similar results in the white population, with a 59% increased risk of targetable genotypes in patients younger than age 50 years. This interesting finding suggests that NSCLC in the young might represent a biologically distinct subgroup of tumors and highlights the importance of urgent molecular analysis of tumors to identify targetable mutations for personalized treatment. Moreover, we found that, although young and old patients underwent similar molecular investigations, in younger patients, therapy had twice as much impact on treatment strategy. The high rate of ALK translocation in the younger population deserves additional investigation in the white population as the rate of ALK positivity in our country is 7%, similar to previous reports.23

Our study shows that younger patients developed more brain metastases in the course of their disease, also described in previous reports.24-26 Duell et al25 recently reported that brain metastases are frequent among younger patients (age < 65 years), females, never smokers, and patients with early-disease stage. Our study did not demonstrate any gender predominance in patients who developed brain metastases, but in both age groups they were significantly more likely to harbor EGFR mutations. This was more significant in patients younger than age 50 years; (55% in the young; 31% in the old; P = .03). Our cohort was too small for multivariable analysis to answer whether driver mutation or age was the main factor that affected brain metastasis development; however, it has been described that brain metastases are more likely to occur in patients with driver mutations, such as EGFR and ALK.27,28

Brain magnetic resonance imaging is not a standard of care in the treatment of LC, including a lack of formal recommendation within the younger cohort (National Comprehensive Cancer Network). We found that, in both age groups, two thirds of patients had metastases detected later in the disease course, indicating a higher index of suspicion in patients even after normal initial brain imaging.

Median survival of patients with brain metastases was worse in patients in both age groups. Having metastasis affected young patients’ survival more than older patients, as younger patients who did not develop brain metastasis had the best median survival (59 months with no metastasis v 25 months with brain metastasis). This difference was not observed in the older cohort in which developing brain metastasis or not did not much affect survival (21 months v 18 months). These findings may suggest a different mechanism of metastatic seeding or underlying tumor biology.

There have been conflicting data about the survival and prognosis of young patients with LC. Some studies have shown prognosis to be worse for younger patients, indicating a more aggressive disease, such as the recent large study by Sacher et al.21 Others have shown that there was no significant difference in survival5; however, it has mostly been demonstrated that younger patients have better prognosis7-11 and this effect was more prominent in early-stage disease.7,10,11 In our study, we concluded that median survival was longer in patients in the younger cohort, but this was not significant, likely because of the small number of patients. When separately analyzing patients younger than age 40 years, we found their survival to be even better than that of older patients, which further supports our finding. The longer survival in the younger cohort was consistent also when normalizing for driver mutations. We could not conclude any difference in survival between patients who presented with early or advanced disease as a result of the paucity of patients.

Interestingly enough, primary tumors were more commonly found in the upper lobes of the lung in patients in the older cohort, whereas in the younger group they were more equally distributed. This may be associated with smoking-related lung cancer, which has an upper lobe tendency.

Our study had several limitations. First, it included a small sample size of young patients. Moreover, data collection and analysis were retrospective and included only one medical center. Limited information was available regarding risk factors, such as occupation, exposure to asbestos, and detailed genetic background.

In conclusion, our study indicates that young patients harbor a higher rate of driver mutations and have an increased incidence of brain involvement. Although we observed no significant difference in overall survival, which could be a result of the small number of younger patients, yet we noticed a trend for better survival in patients in the younger cohort, which could be explained by the higher rate of mutation and respective targeted treatment. This highlights the importance of genetic background assessments and considering LC as a possible diagnosis in young symptomatic patients in clinical settings.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Anna May Suidan, Anna Belilovski Rozenblum, Nir Peled

Administrative support: Maya Ilouze

Provision of study materials or patients: Elizabeth Dudnik

Collection and assembly of data: Anna May Suidan, Laila Roisman, Anna Belilovski Rozenblum, Maya Ilouze, Elizabeth Dudnik, Nir Peled

Data analysis and interpretation: Anna May Suidan, Laila Roisman, Elizabeth Dudnik, Alona Zer, Nir Peled

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Laila Roisman

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Teva Pharmaceuticals

Honoraria: Pfizer, Roche

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Interferon patents, approved

Elizabeth Dudnik

Consulting or Advisory Role: Boehringer Ingelheim

Speakers' Bureau: Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, MSD Oncology, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis

Research Funding: Boehringer Ingelheim

Alona Zer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eli Lilly, Novartis

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst)

Other Relationship: Roche, Eli Lilly, MSD Oncology, AstraZeneca

Nir Peled

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, MSD Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, MSD Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, et al. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995-2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): An analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet. 2011;377:127–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62231-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levi F, Bosetti C, Fernandez E, et al. Trends in lung cancer among young European women: The rising epidemic in France and Spain. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:462–465. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ridge CA, McErlean AM, Ginsberg MS. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2013;30:93–98. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1342949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gadgeel SM, Ramalingam S, Cummings G, et al. Lung cancer in patients < 50 years of age: The experience of an academic multidisciplinary program. Chest. 1999;115:1232–1236. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas A, Chen Y, Yu T, et al. Trends and characteristics of young non-small-cell lung cancer patients in the United States. Front Oncol. 2015;5:113. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subramanian J, Morgensztern D, Goodgame B, et al. Distinctive characteristics of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the young: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:23–28. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c41e8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lara MS, Brunson A, Wun T, et al. Predictors of survival for younger patients less than 50 years of age with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A California Cancer Registry analysis. Lung Cancer. 2014;85:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maruyama R, Yoshino I, Yohena T, et al. Lung cancer in patients younger than 40 years of age. J Surg Oncol. 2001;77:208–212. doi: 10.1002/jso.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold BN, Thomas DC, Rosen JE, et al. Lung cancer in the very young: Treatment and survival in the national cancer data base. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nugent WC, Edney MT, Hammerness PG, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer at the extremes of age: Impact on diagnosis and treatment. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)00745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassidy A, Myles JP, Duffy SW, et al. Family history and risk of lung cancer: Age-at-diagnosis in cases and first-degree relatives. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1288–1290. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbasowa L, Madsen PH. Lung cancer in younger patients. Dan Med J. 2016;63:A5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radzikowska E, Roszkowski K, Głaz P. Lung cancer in patients under 50 years old. Lung Cancer. 2001;33:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramalingam S, Pawlish K, Gadgeel S, et al. Lung cancer in young patients: Analysis of a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:651–657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekine I, Nishiwaki Y, Yokose T, et al. Young lung cancer patients in Japan: Different characteristics between the sexes. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1451–1455. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heist RS, Engelman JA. SnapShot: Non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:448.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cufer T, Ovcaricek T, O’Brien ME. Systemic therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Major-developments of the last 5-years. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1216–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VandenBussche CJ, Illei PB, Lin MT, et al. Molecular alterations in non-small cell lung carcinomas of the young. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:2379–2387. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gitlitz BJ, Morosini D, Sable-Hunt A, et al. The genomics of young lung cancer study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl; abstr TPS1110) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacher AG, Dahlberg SE, Heng J, et al. Association between younger age and targetable genomic alterations and prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:313–320. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian DL, Liu HX, Zhang L, et al. Surgery for young patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shlomi D, Onn D, Gottfried M, et al. Better selection model for EML4-ALK fusion gene test in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Ther. 2013;4:54–58. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sørensen JB, Hansen HH, Hansen M, et al. Brain metastases in adenocarcinoma of the lung: Frequency, risk groups, and prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:1474–1480. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.9.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duell T, Kappler S, Knöfer B, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of brain metastases in patients with newly diagnosed advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat Commun. 2015;4:106–112. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nieder C, Thamm R, Astner ST, et al. Disease presentation and treatment outcome in very young patients with brain metastases from lung cancer. Onkologie. 2008;31:305–308. doi: 10.1159/000129621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iuchi T, Shingyoji M, Itakura M, et al. Frequency of brain metastases in non-small-cell lung cancer, and their association with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:674–679. doi: 10.1007/s10147-014-0760-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villalva C, Duranton-Tanneur V, Guilloteau K, et al. EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, and HER-2 molecular status in brain metastases from 77 NSCLC patients. Cancer Med. 2013;2:296–304. doi: 10.1002/cam4.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]