PURPOSE

Little is known about the genetic predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer among the Chilean population, in particular genetic predisposition beyond BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. In the current study, we aim to describe the germline variants detected in individuals who were referred to a hereditary cancer program in Santiago, Chile.

METHODS

Data were retrospectively collected from the registry of the High-Risk Breast and Ovarian Cancer Program at Clínica Las Condes, Santiago, Chile. Data captured included index case diagnosis, ancestry, family history, and genetic test results.

RESULTS

Three hundred fifteen individuals underwent genetic testing during the study period. The frequency of germline pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in a breast or ovarian cancer predisposition gene was 20.3%. Of those patients who underwent testing with a panel of both high- and moderate-penetrance genes, 10.5% were found to have pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in non-BRCA1/2 genes.

CONCLUSION

Testing for non-BRCA1 and -2 mutations may be clinically relevant for individuals who are suspected to have a hereditary breast or ovarian cancer syndrome in Chile. Comprehensive genetic testing of individuals who are at high risk is necessary to further characterize the genetic susceptibility to cancer in Chile.

INTRODUCTION

In the era of precision medicine, genetic risk assessment is a superb tool with which to evaluate an individual’s underlying susceptibility to disease. Unfortunately, in low- and middle-income countries, access to genetic counseling and testing is scarce.1,2 In Chile, knowledge of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) is mainly limited to BRCA1/2 mutations. Multiple studies report the presence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in HBOC families, and one study reports the presence of nine BRCA1/2 Chilean founder mutations3-10; however, little is known about the relevance of moderate-penetrance variants or non-BRCA1/2 variants in this population.

Our center in Santiago, Chile, established a high-risk program in 2008 to evaluate individuals who may have a hereditary predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer. In the current study, we aim to describe the genetic variants identified and to detail the non-BRCA1/2 variants discovered along with the phenotype of the affected families.

METHODS

Study Design

Data were accessed from the registry of the High-Risk Breast and Ovarian Cancer Program at Clínica Las Condes in Santiago, Chile. This registry contains data on individuals who are referred to the program for suspicion of an HBOC syndrome on the basis of personal or family history. Data were collected from January 1, 2008, to May 31, 2018. Index case demographics, diagnosis, genetic test reports, family history, and histopathology records were abstracted.

Before July 2015, patients that met the criteria for genetic testing as defined by National Cancer Care Network (NCCN) guidelines were tested only for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2.11,12 We used the most current version of the NCCN guidelines to determine eligibility at the time of testing. We performed BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequencing using Sanger sequencing. Depending on laboratory availability and the costs of testing at the time of participation in the registry, molecular analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 consisted of either complete sequencing of all exons and the surrounding regions of BRCA1 and BRCA2, partial sequencing of select exons of BRCA1 and BRCA2, or sequencing for the Ashkenazi-Jewish founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. More details are included in the Data Supplement.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

The frequency of germline mutations in breast and/or ovarian cancer predisposition genes—beyond BRCA1 and BRCA2—is not well reported in Chile. This study describes the pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants identified in a single institution clinical cohort with a personal and/or family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer in Santiago, Chile.

Knowledge Generated

Of 315 individuals studied, 17.1% had a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Of those who underwent panel testing, 9.5% had a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in one or more of the following genes: RAD51C, RAD51D, ATM, PALB2, CHEK2, and CDH1.

Relevance

Given the emerging clinical relevance of pathogenic variants in moderate-penetrance cancer predisposition genes and the significant frequency of such variants in our cohort, this study highlights the importance of multigene germline testing in Chile in individuals who are suspected to be at risk for a hereditary breast or ovarian cancer syndrome.

As a result of emerging evidence for the clinical utility of testing for moderate-penetrance mutations, after July 2015 all patients who met NCCN criteria for genetic testing for HBOC—with the exception of those with a germline mutation already identified in the family—underwent genetic panel testing. The genetic panel selected was based on personal and family history. Panel testing was performed using next-generation sequencing at Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–approved commercial laboratories in the United States. All variants identified using next-generation sequencing were validated by Sanger sequencing or multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. More details are included in the Data Supplement.

For patients with a demonstrated germline mutation in a family member, we performed single-site analysis using Sanger sequencing. Individuals assessed before July 2015 with Sanger sequencing of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in whom a pathogenic variant was not identified were not routinely recalled for expanded screening with next-generation sequencing.

Each commercial laboratory used its own algorithm to classify variants. Classification of variants by academic laboratories in Chile and by the Laboratory of Oncology and Molecular Genetics in Clínica Las Condes was determined using ALAMUT software (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France) and consultation of the following databases: the Breast Cancer Information Core database, Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for research into Familial Breast cancer database, Universal Mutation Database, and the Leiden Open Variation Database. After 2015, the Laboratory of Oncology and Molecular Genetics also consulted the BRCA Exchange and ClinVar databases. Classification of variants in all laboratories was based on the International Agency for Research on Cancer five-tier classification scheme.

Ethical Considerations

The ethics committee of the institution has approved the registry—adhering to the statutes of the Helsinki Declaration—used for this study. All patient information has been deidentified. The registry only contains data from patients who formally consented to participate. All patients who underwent genetic testing received pretest and post-test genetic counseling.

RESULTS

A total of 315 individuals with a personal or family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer underwent germline genetic testing since the initiation of the registry in 2008 to May 31, 2018. All individuals who underwent genetic testing fulfilled NCCN criteria for hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer testing. In total, 64 of 315 individuals studied (20.3%) were found to have a pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) germline variant. Two of the individuals had two germline variants for a total of 66 P/LP variants identified, a 20.9% variant frequency. The majority of variants (81.8%) were in BRCA1 or BRCA2—26 in BRCA1 and 28 in BRCA2 (Table 1). Those with BRCA1/2 mutations include seven individuals with Ashkenazi-Jewish founder mutations (13.0% of all BRCA1/2 variants).

TABLE 1.

Pathogenic and Likely Pathogenic Variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2

Of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants reported, all of those reviewed by the Evidenced-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles are considered pathogenic variants.53 The only variant with conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity was the missense variant in BRCA1, c.5434C>G (p.Pro1812Ala). This variant has not yet been reviewed by Evidenced-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles, but has been classified in ClinVar as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, and variant of uncertain significance; it is classified as pathogenic by the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2. This variant has been observed in several individuals with a personal and family history consistent with HBOC, segregating with disease in two kindreds.36-40 RNA and minigene assays have demonstrated that this variant causes the skipping of exon 22 in most transcripts, which leads to a truncated protein product and disrupts the second BRCA1 C-terminal domain.39,40 It was not observed in approximately 6,500 individuals of European and African American ancestry in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project. On the basis of this evidence, we consider BRCA1 c.5434C>G to be an LP variant.

Of the 315 patients assessed, 105 were tested with genetic panels—all patients tested after July 2015 without an indication for single-site analysis. Nine of 105 individuals assessed with a panel (8.6%) had P variants in non-BRCA1/2 genes, as classified by the commercial laboratory that performed the testing. This includes three P variants in CHEK2, one variant in CDH1, four variants in PALB2, and one variant in RAD51D (Table 2). Two LP variants were identified in non-BRCA1/2 genes, an LP variant in ATM, and an LP variant in RAD51C. These LP variants were found in the same individual; LP variants account for 3.8% of the individuals tested with panels. More details are included in the Data Supplement.

TABLE 2.

Pathogenic and Likely Pathogenic Variants in Non-BRCA Genes

Detailed Review of Non-BRCA1/2 Mutations

Given the lack of data on the presence of moderate-penetrance mutations in the Chilean population, we have detailed the clinical histories of the 11 patients in the registry who were identified as having a P or LP variant in one of the following genes: ATM, CDH1, CHEK2, PALB2, RAD51C, and RAD51D.

RAD51C.

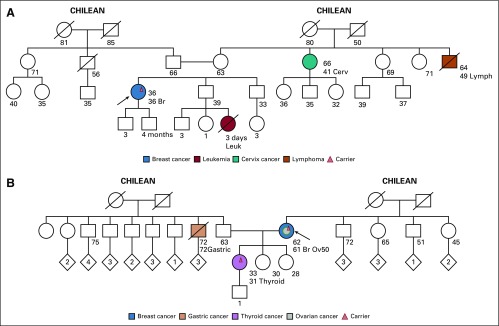

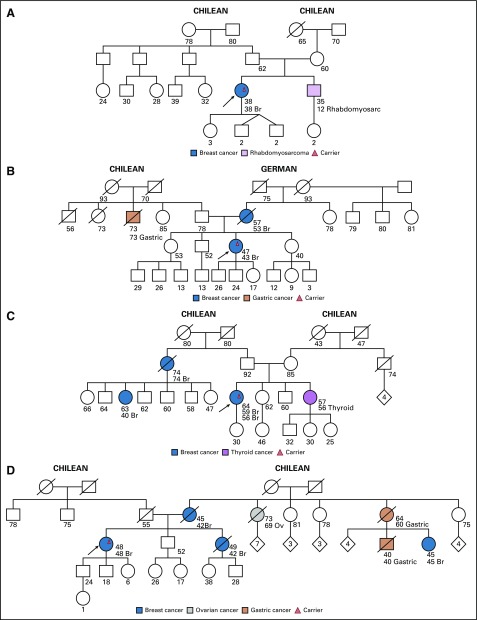

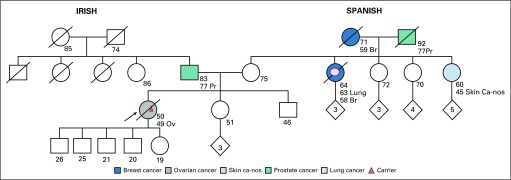

Two unrelated individuals were found to have the same LP variant in RAD51C c.404G>A. The first individual (Fig 1A) is a 36-year-old woman with triple-negative breast cancer. She has no family history of breast or ovarian cancer. RAD51C was included in the genetic analysis because, at the time of pretest counseling, the patient reported that her aunt had been diagnosed with ovarian cancer, which subsequently was determined to be cervix cancer. The second patient (Fig 1B) is a 62-year-old woman with both triple-negative breast cancer and papillary serous ovarian cancer diagnosed at the age of 50 years and 61 years, respectively. She has no other family history of cancer. In addition to the LP variant in RAD51C, she had an LP variant in ATM c.6154G>A. Her daughter, age 33 years and with a history of papillary thyroid cancer, was found to be a carrier of both germline LP variants.

FIG 1.

Families with a likely pathogenic (LP) variant in RAD51C and an LP variant in ATM (all ages are ages provided at the time of first contact with index case). (A) Index case, carrier of LP variant in RAD51C c.404G>A. No family testing has been performed to date. (B) Index case, carrier of both LP variant in RAD51C c.404G>A and LP variant in ATM c.6154G>A. The daughter is also a carrier of both LP variants. Br, breast cancer; Ov, ovarian cancer.

The RAD51C c.404G>A (p.Cys135Tyr) variant results in a G-to-A substitution at nucleotide position 404. This alteration has been reported in Spanish and German families with breast and ovarian cancer.60,61 Consistent with splicing models, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction studies performed on RNA derived from probands in these families demonstrated that this variant results in aberrant splicing, which ultimately leads to a prematurely truncated transcript.61 It has not been observed in large population cohorts.62 In addition, it is predicted that this alteration abolishes the native splice donor site and is likely damaging and deleterious according to PolyPhen and Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant in silico analyses, respectively. On the basis of available evidence to date, this variant is considered likely pathogenic.

The ATM c.6154G>A variant replaces glutamic acid with lysine at codon 2052 of the ATM protein (p.Glu2052Lys). This variant is present in population databases (rs202206540; Exome Aggregation Consortium, 0.03%). It was found to be homozygous in an individual with ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) and heterozygous in an individual affected with breast cancer.54,55 An experimental study that used a lymphoblastoid cell line derived from an A-T affected individual has shown that this missense change causes a defect in RNA splicing with complete loss of the ATM protein. In ClinVar, the variant is annotated as likely pathogenic for a hereditary cancer syndrome; however, we believe more epidemiologic data are required to definitively demonstrate pathogenicity.

CDH1.

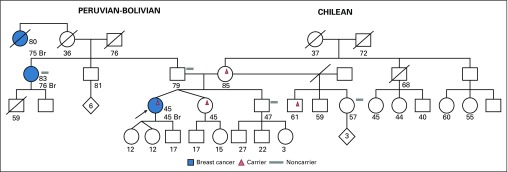

The patient in whom a pathogenic variant in CDH1 was identified (Fig 2) had been diagnosed with invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Single-site analysis demonstrated maternal inheritance; however, on the maternal side of the family, there was no history of gastric cancer or invasive lobular breast cancer. Whereas this variant has been described in some families with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, given this patient’s family history, the significance of this intronic variant for this family is unclear.

FIG 2.

Family with a pathogenic (P) variant in CDH1 (all ages are ages provided at the time of first contact with index case). Index case, carrier of P variant in CDH1 c.1565+2dupT. Mother, maternal half-brother, and monozygotic twin of index case are unaffected carriers. Br, breast cancer.

The c.1565+2dupT intronic pathogenic mutation results from a duplication of a T nucleotide two nucleotide positions after coding exon 10 of the CDH1 gene. This mutation has been reported in multiple individuals with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer and their affected family members.56,63,64 This variant is not present in population databases (Exome Aggregation Consortium, no frequency). Using the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project and ESEfinder splice site prediction tools, it is predicted that this alteration abolishes the native splice donor site, which results in an abnormal protein or transcript that is subject to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. This alteration is classified as a pathogenic variant in available databases.

CHEK2.

All three cases of CHEK2 mutations were patients with breast cancer who were diagnosed at a young age (age 38 years, 39 years, and 47 years). The first patient had no other family history of breast cancer, but her father was diagnosed with prostate cancer at age 64 years (Fig 3A). She is of European ancestry and was found to have the CHEK2 truncating mutation c.1100delC (p.Thr367Metfs*15). This is a well-described pathogenic variant that purportedly increases the risk of breast cancer by approximately two-fold.65,66

FIG 3.

Families with pathogenic (P) variants in CHEK2 (all ages are ages provided at the time of first contact with index case). (A) Index case, carrier of P variant in CHEK2 c.1100delC. No family testing has been performed to date. (B) Index case, carrier of P variant in CHEK2 c.1344delT. No family testing has been performed to date. (C) Index case, carrier of P variant in CHEK2 c.1283C>T. Paternal uncle, carrier of P variant in BRCA2 c.5946delT. Index case tested negative for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Br, breast cancer; CRC, colorectal cancer; Pr, prostate cancer.

The second patient with another CHEK2 truncating mutation, c.1344delT, was of Chilean, Spanish, and Syrian ancestry. She has no first- or second-degree relatives with cancer. She has a maternal second cousin who was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 51 years and another maternal second cousin diagnosed with pancreatic cancer at age 55 years (Fig 3B). The c.1344delT variant, located in coding exon 11 of the CHEK2 gene, causes a translational frameshift with a predicted alternate stop codon (p.Pro449Leufs*20). This pathogenic variant has not yet been described.

The third patient, with a CHEK2 missense mutation, c.1283C>T, is of Ashkenazi Jewish Romanian ancestry and had a family history that was notable for early-onset breast cancer of maternal lineage as well as prostate and breast cancer on the paternal side (Fig 3C). The patient’s brother died of colorectal cancer at age 35 years. Of interest, the paternal side of the family was found to have the BRCA2 Ashkenazi Jewish founder mutation, c.5946delT, for which the patient tested negative. She also tested negative for mutations in mismatch repair genes.

In ClinVar, the CHEK2 c.1283C>T (p.Ser428Phe) variant has conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity. This mutation is located within the kinase domain and has been demonstrated to abolish normal CHEK2 function in yeast.67,68 This mutation has been reported to segregate with disease in one family tested, and it has been estimated to confer an approximate two-fold increased risk of breast cancer among Ashkenazi Jewish carrier women. It has also been identified in multiple unrelated patients with personal and family histories of breast cancer.69,70 On the basis of the supporting evidence, we interpret this alteration as a pathogenic variant.

PALB2.

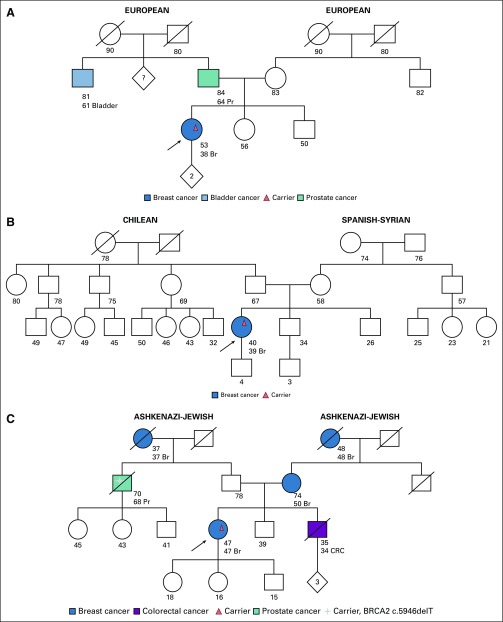

The four patients with PALB2 mutations have varied family histories. The first individual, with a truncating variant (PALB2 c.860dupT, p.Ser288Lysfs*15), was diagnosed with invasive ductal breast cancer at age 38 years. She had no family history of breast cancer; however, she has a small family with few female family members (Fig 4A). This pathogenic variant has been described previously by multiple authors.57,71,72

FIG 4.

Families with pathogenic (P) variants in PALB2 (all ages are ages provided at the time of first contact with index case). (A) Index case, carrier of P variant in PALB2 c.860dupT. No family testing has been performed. (B) Index case, carrier of P variant in PALB2 c.3256C>T. Sister is a carrier. (C) Index case, carrier of P variant in PALB2 c.2964delA. No family testing has been performed to date. (D) Index case, carrier of both a P variant in PALB2 c.2218C>T and P variant in BRCA1 c.3817C>T. Br, breast cancer; Ov, ovarian cancer.

The second individual had a PALB2 nonsense pathogenic variant, c.3256C>T (p.Arg1086*), which has been previously described in families with breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer. She is a 47-year-old female who was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 43 years. Her mother also had breast cancer at age 53 years. A healthy 40-year-old sister of the index case underwent single-site analysis and was found to be a carrier (Fig 4B). This pathogenic nonsense variant has also been previously reported.57,58,71-74

The third individual with a PALB2 P variant was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 56 years and developed a second primary breast cancer 3 years later. She had second- and third-degree relatives with breast cancer of paternal lineage (Fig 4C). The variant detected was a nonsense mutation, c.2964delA (p.Val989*), which has been reported by various clinical laboratories and is predicted to result in loss of function.

Finally, the fourth patient with another pathogenic nonsense variant, c.2218C>T (p.Gln740*), in PALB2 was a woman who had been diagnosed with breast cancer at age 48 years. She had multiple first-degree relatives with breast cancer (Fig 4D); however, she was found to have a concomitant BRCA1 germline mutation, c.3817C>T. Family testing is pending.

RAD51D.

The patient with the RAD51D mutation was a 50-year-old woman with stage IV papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary who was found to have the nonsense pathogenic variant RAD51D c.216C>A. This variant results in a premature stop codon (p.Tyr72*) and has not yet been described. The patient’s family history was relevant for a maternal aunt with breast cancer diagnosed at age 58 years, a maternal grandmother with breast cancer diagnosed at age 59 years, and a maternal first cousin once removed with ovarian cancer diagnosed at age 45 years (Fig 5). To date, no other family members have presented for single-site analysis testing.

FIG 5.

Family with a P variant in RAD51D (all ages are ages provided at the time of first contact with index case). Index case, carrier of P variant in RAD51D c.216C>A. No family testing has been performed to date. Br, breast cancer; Ov, ovarian cancer; Pr, prostate cancer.

DISCUSSION

Our registry represents a high-risk cohort referred for genetic testing in a single institution in Santiago, Chile. In 11 years, we studied 315 patients. In this selected cohort, 20.3% of individuals studied were determined to have a P or LP variant in a breast and/or ovarian cancer high- or moderate-penetrance gene. Of the 105 individuals who underwent genetic panel testing, 8.6% had a P variant and 3.8% had an LP variant in a non-BRCA1/2 gene.

The two most frequent BRCA1/2 mutations in the current study were located in exon 11 of BRCA2: c.4740_4741dupTG and c.5146_5149delTATG. These two mutations account for 24% of BRCA1/2 mutations in our cohort and are considered to be Chilean founder mutations.10 We also report three BRCA1/2 mutations not previously described in the literature: BRCA1 c.3710_3711delTA, BRCA1 c.(4357+1_4358-1)_(4484+1_4485-1)del, and BRCA2 c.3345delT. All three of these mutations are truncating mutations, the second being the complete deletion of intron 13 in BRCA1. In contrast to a recent publication that reported a high cumulative frequency of nine Chilean founder mutations in BRCA1/2, although these variants were observed in our cohort, they only account for 36.3% of all variants.10

In addition to BRCA1/2 mutations, we also identified non-BRCA1/2 P and LP variants in six moderate–high-penetrance genes: ATM, PALB2, CHEK2, CDH1, RAD51C, and RAD51D. Other studies that evaluated these genes in the Chilean population evaluated for single-nucleotide polymorphism or common variant association with risk of disease.75-80 Few studies describe the presence of P or LP moderate-penetrance variants in Chilean clinical cohorts.

Individuals with moderate-penetrance variants in our study have varied family histories, some with first-degree relatives with cancers associated with the variant identified and others with multiple unaffected generations. Variability of presentation is not unexpected for individuals with moderate-penetrance mutations. Unfortunately, given the low frequency of single-site analysis in family members, we cannot definitively comment on the behavior and penetrance of these mutations in our families.

Lack of family testing reflects the barriers to genetic testing in Chile. This is a direct result of various factors: the lack of insurance coverage for genetic testing, the high cost of the exam in Chile, the lack of awareness on the part of health care providers about genetic testing criteria and the availability of the exam, and the lack of genetic counselors in Chile.2 To date, the Chilean public health care system provides no coverage for genetic testing of cancer predisposition genes.

Given such limitations to testing, we recognize that the population in our study represents a select group of individuals. In addition, this study is limited by the lack of homogeneity in BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequencing before 2015. This again reflects the limitation of resources, which early on lead to partial sequencing of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Nevertheless, the utility of multigene testing and the infrequency of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations has been demonstrated in other Latin American cohorts.81-83 For these reasons and in light of the non-BRCA1/2 mutations identified in this cohort, we do not advocate for the use of a limited screening panel to evaluate for Chilean founder mutations, as has been suggested by other authors.10

In conclusion, our understanding of the spectrum of germline mutations that may be present in the Chilean population is far from complete. We report the presence of BRCA1/2 and non-BRCA1/2 variants in a cohort of individuals with a personal or family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer. All variants identified are in clinically actionable genes. Recognition at the public health level of the importance of genetic testing is essential to facilitate a more systematic evaluation of patients who are at risk and a more precise understanding of the frequency of non-BRCA1/2 mutations in the population.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Christina Adaniel, Nuvia Aliaga, Francisco Lopez, Claudia Hurtado

Administrative support: Maria Eugenia Bravo

Provision of study materials or patients: Francisca Salinas, Octavio Peralta, Hernando Paredes, Antonio Sola, Carolina Behnke, Tulio Rodriguez, Soledad Torres, Francisco Lopez

Collection and assembly of data: Christina Adaniel, Francisca Salinas, Maria Eugenia Bravo, Octavio Peralta, Nuvia Aliaga, Antonio Sola, Paulina Neira, Soledad Torres, Claudia Hurtado

Data analysis and interpretation: Christina Adaniel, Juan Manuel Donaire, Hernando Paredes, Nuvia Aliaga, Carolina Behnke, Tulio Rodriguez, Francisco Lopez, Claudia Hurtado

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Juan Manuel Donaire

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0535-2. Zhong A, Darren B, Dimaras H: Ethical, social, and cultural issues related to clinical genetic testing and counseling in low- and middle-income countries: Protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 6:140, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. doi: 10.24875/ric.17002195. Chavarri-Guerra Y, Blazer KR, Weitzel JN: Genetic cancer risk assessment for breast cancer in Latin America. Rev Invest Clin 69:94-102, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872004000200010. Gallardo M, Faúndez P, Cruz A, et al: Determination of a BRCA1 gene mutation in a family with hereditary breast cancer [in Spanish]. Rev Med Chil 132:203-210, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(04)74590-x. Campos B, Díez O, Alvarez C, et al: Haplotype of the BRCA2 6857delAA mutation in 4 families with breast/ovarian cancer [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc) 123:543-545, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9047-1. Gallardo M, Silva A, Rubio L, et al: Incidence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in 54 Chilean families with breast/ovarian cancer, genotype-phenotype correlations. Breast Cancer Res Treat 95:81-87, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.08.019. Jara L, Ampuero S, Santibáñez E, et al: BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a South American population. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 166:36-45, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1170-y. Gonzalez-Hormazabal P, Gutierrez-Enriquez S, Gaete D, et al: Spectrum of BRCA1/2 point mutations and genomic rearrangements in high-risk breast/ovarian cancer Chilean families. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126:705-716, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1382-9. Sanchez A, Faundez P, Carvallo P: Genomic rearrangements of the BRCA1 gene in chilean breast cancer families: An MLPA analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 128:845-853, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0416. Ossa CA, Torres D: Founder and recurrent mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Latin American countries: State of the art and literature review. Oncologist 21:832-839, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18815. Alvarez C, Tapia T, Perez-Moreno E, et al: BRCA1 and BRCA2 founder mutations account for 78% of germline carriers among hereditary breast cancer families in Chile. Oncotarget 8:74233-74243, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daly MB, Pilarski R, Axilbund JE, et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Breast and ovarian, version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:153–162. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Guidelines: Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Breast and ovarian (version 1.2018). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_screening.pdf.

- 13. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-392. Simard J, Tonin P, Durocher F, et al: Common origins of BRCA1 mutations in Canadian breast and ovarian cancer families. Nat Genet 8:392-398, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. doi: 10.1002/humu.9014. Llort G, Muñoz CY, Tuser MP, et al: Low frequency of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Spain. Hum Mutat 19:307, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010101)91:1<137::aid-ijc1020>3.0.co;2-r. de la Hoya M, Pérez-Segura P, Van Orsouw N, et al: Spanish family study on hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer: Analysis of the BRCA1 gene. Int J Cancer 91:137-140, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. doi: 10.1007/s13167-010-0037-y. Janavičius R: Founder BRCA1/2 mutations in the Europe: Implications for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer prevention and control. EPMA J 1:397-412, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwong A, Ng EK, Wong CL, et al. Identification of BRCA1/2 founder mutations in Southern Chinese breast cancer patients using gene sequencing and high resolution DNA melting analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2698-y. Rashid MU, Muhammad N, Bajwa S, et al: High prevalence and predominance of BRCA1 germline mutations in Pakistani triple-negative breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 16:673, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12610. Fernandes GC, Michelli RA, Galvão HC, et al: Prevalence of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in a Brazilian population sample at-risk for hereditary breast cancer and characterization of its genetic ancestry. Oncotarget 7:80465-80481, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3948-z. Pinto P, Paulo P, Santos C, et al: Implementation of next-generation sequencing for molecular diagnosis of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer highlights its genetic heterogeneity. Breast Cancer Res Treat 159:245-256, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-1-20. Solano AR, Aceto GM, Delettieres D, et al: BRCA1 And BRCA2 analysis of Argentinean breast/ovarian cancer patients selected for age and family history highlights a role for novel mutations of putative south-American origin. Springerplus 1:20, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00717.x. Han SH, Lee KR, Lee DG, et al: Mutation analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 from 793 Korean patients with sporadic breast cancer. Clin Genet 70:496-501, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0680-y. Esteban Cardeñosa E, Bolufer Gilabert P, de Juan Jimenez I, et al: Broad BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutational spectrum and high incidence of recurrent and novel mutations in the eastern Spain population. Breast Cancer Res Treat 121:257-260, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9498-y. Schneegans SM, Rosenberger A, Engel U, et al: Validation of three BRCA1/2 mutation-carrier probability models Myriad, BRCAPRO and BOADICEA in a population-based series of 183 German families. Fam Cancer 11:181-188, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. doi: 10.1186/bcr3218. Lecarpentier J, Noguès C, Mouret-Fourme E, et al: Variation in breast cancer risk associated with factors related to pregnancies according to truncating mutation location, in the French National BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations carrier cohort (GENEPSO). Breast Cancer Res 14:R99, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. doi: 10.1111/cge.12441. Peixoto A, Santos C, Pinto P, et al: The role of targeted BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation analysis in hereditary breast/ovarian cancer families of Portuguese ancestry. Clin Genet 88:41-48, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9622-2. de Juan Jiménez I, García Casado Z, Palanca Suela S, et al: Novel and recurrent BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in early onset and familial breast and ovarian cancer detected in the Program of Genetic Counseling in Cancer of Valencian Community (eastern Spain). Relationship of family phenotypes with mutation prevalence. Fam Cancer 12:767-777, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Greenman J, Mohammed S, Ellis D, et al: Identification of missense and truncating mutations in the BRCA1 gene in sporadic and familial breast and ovarian cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 21:244-249, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9378-6. Gomes MC, Costa MM, Borojevic R, et al: Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer patients from Brazil. Breast Cancer Res Treat 103:349-353, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3293-7. Wong-Brown MW, Meldrum CJ, Carpenter JE, et al: Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 150:71-80, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu172. Song H, Cicek MS, Dicks E, et al: The contribution of deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2 and the mismatch repair genes to ovarian cancer in the population. Hum Mol Genet 23:4703-4709, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1160. Caputo S, Benboudjema L, Sinilnikova O, et al: Description and analysis of genetic variants in French hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families recorded in the UMD-BRCA1/BRCA2 databases. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D992-D1002, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Couch FJ, Weber BL. Mutations and polymorphisms in the familial early-onset breast cancer (BRCA1) gene. Breast Cancer Information Core. Hum Mutat. 1996;8:8–18. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380080102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peelen T, van Vliet M, Petrij-Bosch A, Mieremet R, et al: A high proportion of novel mutations in BRCA1 with strong founder effects among Dutch and Belgian hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families. Am J Hum Genet 60:1041-1049, 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.203. Hamel N, Feng BJ, Foretova L, et al: On the origin and diffusion of BRCA1 c.5266dupC (5382insC) in European populations. Eur J Hum Genet 19:300-306, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Díez O, Osorio A, Durán M, et al. Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Spanish breast/ovarian cancer patients: A high proportion of mutations unique to Spain and evidence of founder effects. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:301–312. doi: 10.1002/humu.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.10.200. Kaufman B, Laitman Y, Carvalho MA, et al: The P1812A and P25T BRCA1 and the 5164del4 BRCA2 mutations: Occurrence in high-risk non-Ashkenazi Jews. Genet Test 10:200-207, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9571-2. Konstantopoulou I, Rampias T, Ladopoulou A, et al: Greek BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation spectrum: Two BRCA1 mutations account for half the carriers found among high-risk breast/ovarian cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 107:431-441, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.074047. Gaildrat P, Krieger S, Théry JC, et al: The BRCA1 c.5434C->G (p.Pro1812Ala) variant induces a deleterious exon 23 skipping by affecting exonic splicing regulatory elements. J Med Genet 47:398-403, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9916-2. Jarhelle E, Riise Stensland HM, Mæhle L, et al: Characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants found in a Norwegian breast or ovarian cancer cohort. Fam Cancer 16:1-16, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.6.361. Bergthorsson JT, Ejlertsen B, Olsen JH, et al: BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation status and cancer family history of Danish women affected with multifocal or bilateral breast cancer at a young age. J Med Genet 38:361-368, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. doi: 10.1002/humu.21414. Caux-Moncoutier V, Castéra L, Tirapo C, et al: EMMA, a cost- and time-effective diagnostic method for simultaneous detection of point mutations and large-scale genomic rearrangements: Application to BRCA1 and BRCA2 in 1,525 patients. Hum Mutat 32:325-334, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4703. Vogel KJ, Atchley DP, Erlichman J, et al: BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing in Hispanic patients: Mutation prevalence and evaluation of the BRCAPRO risk assessment model. J Clin Oncol 25:4635-4641, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156789. Zhong X, Dong Z, Dong H, et al: Prevalence and prognostic role of BRCA1/2 variants in unselected Chinese breast cancer patients. PLoS One 11:e0156789, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neuhausen SL, Godwin AK, Gershoni-Baruch R, et al. Haplotype and phenotype analysis of nine recurrent BRCA2 mutations in 111 families: Results of an international study. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1381–1388. doi: 10.1086/301885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Q, Adebamowo CA, Fackenthal J, et al. Protein truncating BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in African women with pre-menopausal breast cancer. Hum Genet. 2000;107:192–194. doi: 10.1007/s004390000342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Luijt RB, van Zon PHA, Jansen RP, et al. De novo recurrent germline mutation of the BRCA2 gene in a patient with early onset breast cancer. J Med Genet. 2001;38:102–105. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.2.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carraro DM, Koike Folgueira MA, Garcia Lisboa BC, et al. Comprehensive analysis of BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53 germline mutation and tumor characterization: A portrait of early-onset breast cancer in Brazil. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lolas Hamameh S, Renbaum P, Kamal L, et al. Genomic analysis of inherited breast cancer among Palestinian women: Genetic heterogeneity and a founder mutation in TP53. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:750–756. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Salgado J, Zabalegui N, García-Amigot F, et al: Structure-based assessment of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a small Spanish population. Oncol Rep 14:85-88, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29058. Villarreal-Garza C, Alvarez-Gómez RM, Pérez-Plasencia C, et al: Significant clinical impact of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Mexico. Cancer 121:372-378, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3662-2. Yablonski-Peretz T, Paluch-Shimon S, Gutman LS, et al: Screening for germline mutations in breast/ovarian cancer susceptibility genes in high-risk families in Israel. Breast Cancer Res Treat 155:133-138, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spurdle AB, Healey S, Devereau A, et al. ENIGMA: Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles: An international initiative to evaluate risk and clinical significance associated with sequence variation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:2–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.21628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. doi: 10.1086/302418. Teraoka SN, Telatar M, Becker-Catania S, et al: Splicing defects in the ataxia-telangiectasia gene, ATM: Underlying mutations and consequences. Am J Hum Genet 64:1617-1631, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30428. Kraus C, Hoyer J, Vasileiou G, et al: Gene panel sequencing in familial breast/ovarian cancer patients identifies multiple novel mutations also in genes others than BRCA1/2. Int J Cancer 140:95-102, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31815e7f1a. Rogers WM, Dobo E, Norton JA, et al: Risk-reducing total gastrectomy for germline mutations in E-cadherin (CDH1): Pathologic findings with clinical implications. Am J Surg Pathol 32:799-809, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0627-7. Thompson E, Gorringe KL, Rowley SM, et al: Prevalence of PALB2 mutations in Australian familial breast cancer cases and controls. Breast Cancer Res 17:111, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. doi: 10.1126/science.1171202. Jones S, Hruban RH, Kamiyama M, et al: Exomic sequencing identifies PALB2 as a pancreatic cancer susceptibility gene. Science 324:217, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. doi: 10.1111/cge.12548. Sopik V, Akbari MR, Narod SA: Genetic testing for RAD51C mutations: In the clinic and community. Clin Genet 88:303-312, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds115. Osorio A, Endt D, Fernández F, et al: Predominance of pathogenic missense variants in the RAD51C gene occurring in breast and ovarian cancer families. Hum Mol Genet 21:2889-2898, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neidhardt G, Becker A, Hauke J, et al. The RAD51C exonic splice-site mutations c.404G>C and c.404G>T are associated with familial breast and ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2017;26:165–169. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0428-9. Nadauld LD, Garcia S, Natsoulis G, et al: Metastatic tumor evolution and organoid modeling implicate TGFBR2 as a cancer driver in diffuse gastric cancer. Genome Biol 15:428, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kluijt I, Siemerink EJ, Ausems MG, et al. CDH1-related hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome: Clinical variations and implications for counseling. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:367–376. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0687. Thompson D, Seal S, Schutte M, et al: A multicenter study of cancer incidence in CHEK2 1100delC mutation carriers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15:2542-2545, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.08.005. Leedom TP, LaDuca H, McFarland R, et al: Breast cancer risk is similar for CHEK2 founder and non-founder mutation carriers. Cancer Genet 209:403-407, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi052. Shaag A, Walsh T, Renbaum P, et al: Functional and genomic approaches reveal an ancient CHEK2 allele associated with breast cancer in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Hum Mol Genet 14:555-563, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds101. Roeb W, Higgins J, King MC: Response to DNA damage of CHEK2 missense mutations in familial breast cancer. Hum Mol Genet 21:2738-2344, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.024. Maxwell KN, Hart SN, Vijai J, et al: Evaluation of ACMG-guideline-based variant classification of cancer susceptibility and non-cancer-associated genes in families affected by breast cancer. Am J Hum Genet 98:801-817, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4038-y. Moran O, Nikitina D, Royer R, et al: Revisiting breast cancer patients who previously tested negative for BRCA mutations using a 12-gene panel. Breast Cancer Res Treat 161:135-142, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.06.003. Park JY, Zhang F, Andreassen PR: PALB2: The hub of a network of tumor suppressors involved in DNA damage responses. Biochim Biophys Acta 1846:263-275, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70142-7. Cybulski C, Kluźniak W, Huzarski T, et al: Clinical outcomes in women with breast cancer and a PALB2 mutation: A prospective cohort analysis. Lancet Oncol 16:638-644, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-7-11. Grant RC, Al-Sukhni W, Borgida AE, et al: Exome sequencing identifies nonsegregating nonsense ATM and PALB2 variants in familial pancreatic cancer. Hum Genomics 7:11, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv214. Ramus SJ, Song H, Dicks E, et al: Germline mutations in the BRIP1, BARD1, PALB2, and NBN genes in women with ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 107:djv214, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-117. Gonzalez-Hormazabal P, Bravo T, Blanco R, et al: Association of common ATM variants with familial breast cancer in a South American population. BMC Cancer 8:117, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2359-z. Jara L, Gonzalez-Hormazabal P, Cerceño K, et al: Genetic variants in FGFR2 and MAP3K1 are associated with the risk of familial and early-onset breast cancer in a South-American population. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137:559-569, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.05.024. Jara L, Acevedo ML, Blanco R, et al: RAD51 135G>C polymorphism and risk of familial breast cancer in a South American population. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 178:65-69, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1656-2. Gonzalez-Hormazabal P, Reyes JM, Blanco R, et al: The BARD1 Cys557Ser variant and risk of familial breast cancer in a South-American population. Mol Biol Rep 39:8091-8098, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1033-3. Leyton Y, Gonzalez-Hormazabal P, Blanco R, et al: Association of PALB2 sequence variants with the risk of familial and early-onset breast cancer in a South-American population. BMC Cancer 15:30, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9544-5. Tapia T, Sanchez A, Vallejos M, et al: ATM allelic variants associated to hereditary breast cancer in 94 Chilean women: Susceptibility or ethnic influences? Breast Cancer Res Treat 107:281-288, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alemar B, Herzog J, Brinckmann Oliveira Netto C, et al. Prevalence of Hispanic BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among hereditary breast and ovarian cancer patients from Brazil reveals differences among Latin American populations. Cancer Genet. 2016;209:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Solano AR, Cardoso FC, Romano V, et al. Spectrum of BRCA1/2 variants in 940 patients from Argentina including novel, deleterious and recurrent germline mutations: Impact on healthcare and clinical practice. Oncotarget. 2016;8:60487–60495. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cock-Rada AM, Ossa CA, Garcia HI, et al. A multi-gene panel study in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in Colombia. Fam Cancer. 2018;17:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s10689-017-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]