Abstract

Telomere length (TL) decreases with cellular aging and biologic stressors. As advanced donor and recipient age are risk factors for chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD), we hypothesized that decreased age-adjusted donor TL would predict earlier onset of CLAD. Shorter donor TL was associated with increased risk of CLAD or death (HR 1.26 per 1-kb TL decrease, 95%CI 1.03-1.54), particularly for young donors. Recipient TL was associated with cytopenias but not CLAD. Shorter TL was also seen in airway epithelium for subjects progressing to CLAD (P = 0.02). Allograft telomere length may contribute to CLAD pathogenesis and facilitate risk stratification.

INTRODUCTION:

Chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) reflects progressive fibrosis and constitutes the most common cause of death after the first year following transplant1. However, time to development of CLAD varies substantially across lung transplant recipients. While donor and recipient age are risk factors for decreased CLAD-free survival, they do not fully capture the extent of molecular aging.2

Telomeres are nucleoprotein caps on the terminal region of chromosomes that provide protection from chromosomal shortening during cell replication. TLs vary inversely with age but are widely distributed within cells and cell populations. TL shortening past a critical length triggers cellular senescence. Accelerated telomere attrition is associated with increased cell turnover and stress, while inherited or sporadic mutations in telomerase-associated genes cause syndromes mimicking early aging.3

Short allograft TL has been associated with delayed graft function and chronic allograft dysfunction following renal transplantation4 and poor graft survival following stem-cell transplant for aplastic anemia.5 Case series of recipients with known telomerase mutations following lung transplantation suggest an increased risk of leukopenia but did not evaluate CLAD.6 A small retrospective lung transplantation cohort study found no association between donor or recipient peripheral blood TL and survival.7

Telomere dysfunction in lung disease has been increasingly appreciated, as telomere-related mutations are implicated in familial pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.8 Experimentally, telomere dysfunction induced by selective deletion of the shelterin complex proteins in alveolar type II cells results in epithelial cell failure, remodeling, and fibrosis.9

These observations motivated the hypothesis that shortened donor peripheral blood telomeres would identify lung allografts at increased risk for early CLAD or death following transplantation.

METHODS:

See supplement for detailed methods. Briefly, lung allograft recipients at UCSF were included if they provided informed consent, donor and recipient DNA samples were available, and had at least 18 months of follow up data (Supplemental Table 1). We measured TL by quantitative PCR on DNA isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) or spleen. For the sub-cohort described in Supplemental Table 4, TL in endobronchial biopsies collected within 90 days following transplant was measured by quantitative Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (Q-FISH).

RESULTS:

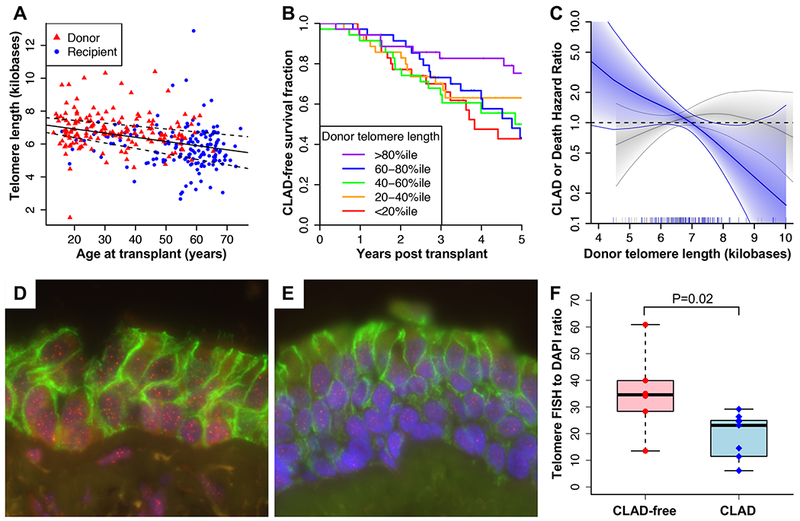

Demographic features of the 175 included subjects are summarized in Supplemental Table 2. Mean donor TL exceeded that of recipients by 1.0 kb (95% CI 0.8-1.2, P <0.001) and by 0.5 kb (95% CI 0.2-0.7, P <0.001) after adjusting for age. Forty-five percent of recipients developed CLAD with a median time to CLAD of 3.8 years and 28% of subjects died. Median follow up time was 4.9 years (IQR 4.0 years). TL was inversely correlated to age for the entire cohort (Figure 1A).

Figure 1: Short donor telomere length in peripheral blood and airway biopsies is associated with decreased CLAD-free survival.

(A) Telomere length in kilobases versus age in years for donors (red triangles) and recipients (blue circles). Linear regression of telomere length versus age across both cohorts resulted in a slope of −25 (95% CI −17 to −32) base pairs per year. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot showing CLAD-free survival stratified by quintiles of donor telomere length. Improved CLAD-free survival was seen across increasing quintiles of donor telomere length (P = 0.04), with improved survival in the >80%ile group compared with the <20%ile group (P = 0.02). Increasing quintile of recipient telomere length was not associated with CLAD-free survival (P = 0.59). (C) Hazard ratios for CLAD or death per 1 KB decrease in telomere length stratified by donor age under 30 (blue) or over 30 (grey) and adjusted for subject characteristics in Supplemental Table 2 are plotted against donor telomere length. Solid line shows spline fit of data with shaded area indicating 95% confidence intervals. (D-E) Quantification of telomere length in airway epithelial cells from lung transplant recipients who would either develop CLAD or remain CLAD-free. Endobronchial biopsies collected during surveillance bronchoscopy within the first 90 days post-transplant (median 31 days) were stained for telomeric DNA (red), E-cadherin (green), and total DNA (DAPI, blue). Shown are representative images from (D) a CLAD-free subject with a telomere to DAPI ratio of 40 and (E) a CLAD subject with a telomere to DAPI ratio of 15. As shown in (F), telomere length was higher in CLAD-free subjects than in subjects with CLAD (P = 0.02 by Mann Whitney test).

Shorter donor TL was associated with an increased risk of CLAD or death with an adjusted HR of 1.25 per 1-kb decrease in TL (95% CI 1.03-1.52, 88 events, P = 0.02, Figures 1B–C). Recipient TL and donor age were not associated with CLAD-free survival (Table 1). Interaction modeling suggested that short donor telomeres are most hazardous in younger donors (P = 0.01). In a competing risks analysis adjusted for subject characteristics, decreasing donor TL was associated with both CLAD censored on death (subdistribution HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.00-1.56, 72 events, P = 0.045) and death alone (subdistribution HR 1.43, 95% CI 1.06-1.93, 40 events, P = 0.02).

Table 1:

Cox proportional hazards models for CLAD-free survival as a function of donor and recipient telomere length.

| Multivariable risk of CLAD or death model†‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Telomere length (per 1 kb decrease) | |||

| Donor | 1.25 | 1.03 - 1.52 | 0.02 |

| Recipient | 1.02 | 0.87 - 1.2 | 0.79 |

| Age (per decade) | |||

| Donor | 1.03 | 0.86 - 1.22 | 0.76 |

| Recipient | 1.06 | 0.8 - 1.41 | 0.67 |

| Multivariable risk of CLAD or death interaction model† | |||

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Telomere length (per 1 kb decrease) | |||

| Donor | 2.39 | 1.4 - 4.07 | 0.001 |

| Age (per decade) | |||

| Donor | 0.29 | 0.11 - 0.79 | 0.02 |

| Donor Age * Donor Telomere length | |||

| Interaction | 0.83 | 0.71 - 0.96 | 0.01 |

| Donor-age stratified, multivariable-adjusted risk of CLAD or death models† | |||

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Donor telomere length (per 1 kb decrease) | |||

| Donor Age <30 | 1.65 | 1.18 - 2.31 | 0.004 |

| Donor Age ≥30 | 1 | 0.79 - 1.27 | 0.97 |

Includes donor and recipient telomere length, age, diagnosis group, lung allocation score, donor gender, recipient gender, non-Hispanic white donor, non-Hispanic white recipient, transplant type, and donor “ever smoker” status.

Univariable and multivariable models including all covariates are included as Supplemental Table 3.

An increased odds ratio of mild (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.1-5.5) and severe leukopenia (OR 4.8, 95% CI 1.8-13.0) was found amongst recipients in the lowest 20th percentile of PBMC TL (Supplemental Table 5).

Endobronchial TL was measured in subjects with extremes of time to CLAD to determine the association with allograft TL. The populations are described in Supplemental Table 4. Endobronchial TL was significantly greater in the >8 year CLAD-free group, relative to those that developed CLAD at a median of 2.9 years (P = 0.02, Figure 1F).

DISCUSSION:

In summary, short donor PBMC TL was associated with worse CLAD-free survival, independent of donor age, in univariable and multivariable models, while recipient TL was associated with increased incidence of post-transplant leukopenia. TL was also shorter in airway epithelial cells from lung allografts that went on to develop CLAD, suggesting that decreased TL within the lung may directly contribute to the development of CLAD.

Genetic predisposition or environmental insults affecting the lung may contribute to short telomeres. Telomere shortening beyond what is expected with aging might signify systemic or inherited telomere dysfunction, which may explain the observed interaction with donor age. Cell turnover that is either homeostatic or in response to injury is impaired in the context of critically short telomeres. Allografts with short telomeres may have a higher frequency of senescent cells and thus be at increased risk for the airway-centric or parenchymal lung fibrosis that are pathologic correlates of CLAD.1 Lung allografts may be particularly susceptible to telomere attrition because of repeated environmental insults or high rates of cell turnover relative to other solid organs.10

Recipient PBMC TL was associated with clinically significant leukopenia, consistent with previous reports of increased leukopenia in lung allograft recipients with telomerase mutations.6 Short PBMC TL may reflect a larger population of senescent bone marrow cells unable to increase leukocyte production, particularly under the influence of immunosuppressive medications. Assessment of recipient TL has the potential to guide post-transplantation immunosuppressive and antiviral dosing.

Strengths of this study include the large sample size relative to other investigations of TL in lung transplantation,7 length of follow up, uniform assessment of TL with quality controls, and confirmation with measurement of TL in airway tissue. The study is from a single center, limiting differences in clinical practice; however, external validation would strengthen the generalizability of the findings. In particular, relative to ISHLT registry reports, this cohort included more recipients transplanted for pulmonary fibrosis.2 Also, we did not evaluate TL relevance for subjects with <18 months follow up.

Our findings, if replicated, may assist with improved stratification of donor risk, and facilitate the use of lungs from donors of advanced age if TL is found to be adequate. Telomerase activation may be of interest in allografts with short TL.3

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the patients who generously donated lung tissue and blood for this study. This work was supported by the Nina Ireland Program for Lung Health (J.R.G., P.J.W.), VA grant 1IK2CX001034-01A2 (J.R.G), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grants P01HL108794 (P.J.W), and 5T32HL007185-37 (H.E.F.).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no competing financial interests.

References:

- 1.Todd JL, Palmer SM. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: the final frontier for lung transplantation. Chest 2011;140(2):502–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-second Official Adult Heart Transplantation Report--2015; Focus Theme: Early Graft Failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34(10):1244–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jager K, Walter M. Therapeutic Targeting of Telomerase. Genes (Basel) 2016;7(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domanski L, Kloda K, Kwiatkowska E, et al. Effect of delayed graft function, acute rejection and chronic allograft dysfunction on kidney allograft telomere length in patients after transplantation: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2015;16:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gadalla SM, Wang T, Haagenson M, et al. Association between donor leukocyte telomere length and survival after unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for severe aplastic anemia. JAMA 2015;313(6):594–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tokman S, Singer JP, Devine MS, et al. Clinical outcomes of lung transplant recipients with telomerase mutations. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34(10):1318–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtwright AM, Fried S, Villalba JA, et al. Association of Donor and Recipient Telomere Length with Clinical Outcomes following Lung Transplantation. PLoS One 2016;11(9):e0162409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alder JK, Chen JJ, Lancaster L, et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105(35):13051–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naikawadi RP, Disayabutr S, Mallavia B, et al. Telomere dysfunction in alveolar epithelial cells causes lung remodeling and fibrosis. JCI Insight;1(14). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Vlaminck I, Martin L, Kertesz M, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of infection and rejection after lung transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112(43):13336–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.