Abstract

The leading cause of non-HIV-related mortality is liver disease. Fatty liver disease can be characterized as alcoholic or nonalcoholic in nature. Alcohol use is prevalent among individuals with HIV infection and can lead to medication nonadherence, lower CD4+ cell count, inadequate viral suppression, and disease progression. The pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in individuals with HIV infection includes metabolic syndrome, hyperuricemia, HIV-related lipodystrophy, genetic polymorphisms, medications, HIV itself, and the gut microbiome. The prevalence of NAFLD in persons with HIV infection ranges from 30% to 65% depending on the modality of diagnosis. Individuals with HIV infection and NAFLD are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease; however, there is a dearth of longitudinal outcomes studies on this topic. Current therapies for NAFLD, such as vitamin E and pioglitazone, have not been studied in persons with HIV infection. There are several drugs in phase II and III clinical trials that specifically target NAFLD in HIV, including CC chemokine receptor 5 inhibitors, growth hormone-releasing factor agonists, and stearoyl-CoA desaturase inhibitors. Persons with HIV should be screened for NAFLD while pursuing aggressive risk factor modification and lifestyle changes, given the increased risk of cardiovascular mortality.

Keywords: HIV, liver, fatty liver disease, NASH, NAFLD, nonalcoholic, alcoholic, steatohepatitis

Introduction

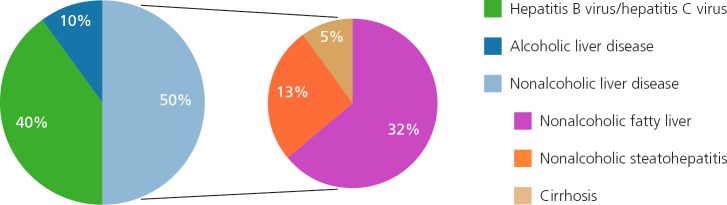

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is now the second leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States and is projected to become the major etiology within the next decade.1 The prevalence of NAFLD among the US population is approximately 30%, with an estimated 25% of those individuals having nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), the more severe and progressive subtype. NAFLD is not only the most common etiology of chronic liver disease in the general population but also in individuals with HIV infection (See Figure 1).2–4

Figure 1.

Prevalence of alcoholic and subtypes of nonalcoholic liver disease varies depending on the modality used for diagnosis, but is also attributable to varying definitions of alcohol abuse, variability of alcohol use, and social stigma; therefore, the true prevalence is unclear.

Since the development of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), liver disease remains one of the leading causes of non-HIV-related mortality.5,6 HIV-related liver disease has a wide variety of etiologies, including coinfection with hepatitis B or C virus, NAFLD, alcoholic liver disease, medication-related hepatotoxicity, and potentially the virus itself.7

Subtypes of Fatty Liver and Fatty Liver Disease

The presence of fat in the liver does not automatically mean that liver disease is present. Indeed, normal physiologic processes include temporary storage of fat in the liver prior to processing and distribution. Longer-term storage of fat in hepatocytes may lead to increased cell turnover and subsequent development of an immune-mediated response, as well as fibrosis. Simple ste-atosis (fatty liver) can be distinguished from fatty liver disease by the presence of serum transaminase abnormalities (injury) or by the development of fibrosis. Fatty liver disease is broadly differentiated by its underlying etiology into alcoholic versus nonalcoholic forms. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and NAFLD are histologically similar; therefore, clinical history must be taken into consideration, which is often challenging when dealing with the stigma and misconceptions associated with alcohol use.

Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

ALD can range from alcoholic steatosis to alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and, ultimately, advanced liver disease in the form of cirrhosis. Alcoholic steatosis is simple steatosis, a direct consequence of alcohol oxidation, and is typically benign and reversible with abstinence.8 In the majority of cases, steatosis is macrovesicular in nature. However, the presence of mixed steatosis (macro- and microvesicular) has been associated with higher risk (28% vs 3%, respectively) of progression to cirrhosis over a median interval of 10.5 years than with purely macrovesicular steatosis.9 A proposed mechanism of progression of liver disease includes oxidative stress, which may promote the formation of giant mitochondria. The presence of giant mitochondria is also a histologic predictor of ALD progression to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.9

ASH is characterized by the presence of macrovesicular steatosis, Mallory-Denk bodies, neutrophilic infiltration, and hepatocyte ballooning, the latter of which distinguishes ASH from simple steatosis. Ballooned hepatocytes, Mallory-Denk bodies, and lobular inflammation are primarily located in zone 3 (the pericentral portion of the liver lobule), promoting the eventual development of zone 3 fibrosis. A differentiating feature of ASH is the predominant lobular infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, compared with portal tract infiltration of mononuclear cells in other types of hepatitis.8 Severe neutrophilic infiltration is often a feature of ASH.

ASH (often referred to as alcoholic hepatitis) is a clinical diagnosis based on development of jaundice plus aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevations 5 to 10 times the upper limit of normal, with ALT classically being lower, in the setting of alcohol use within 8 weeks.10 There is a marked short-term mortality of up to 30%. In cases where alcohol use is unclear or there may be confounding etiologies, liver biopsy is utilized to confirm the diagnosis. In order to assist with prognostication, the Alcoholic Hepatitis Histologic Score was developed.11 Histologic features, including degree of fibrosis, degree of neutrophilic infiltration, type of bilirubinostasis, and presence of megamitochondria were associated with 90-day mortality (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUROC], 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.71–0.83). In fact, features such as severe neutrophilic infiltration and presence of megamitochondria portended a better prognosis than do features of advanced fibrosis and canalicular with hepatocellular bilirubinostasis, which predicted higher mortality.11

In individuals with ongoing injury, cirrhosis will eventually develop. Those who progress to cirrhosis will have perivenular and perisinusoidal fibrosis with micronodular versus macronodular cirrhosis if they continue to actively use alcohol.8 In fact, fibrosis stage is the main long-term predictor of mortality in persons with compensated ALD, with a 10-year mortality of 45% in those with advanced fibrosis (Metavir score, F3/F4; P <.001).12

Alcohol use is prevalent among individuals with HIV infection and can lead to medication nonadherence, disease progression, and inadequate viral suppression. One large-scale study of more than 1000 participants found that 10% participated in hazardous alcohol use (defined as >14 drinks/week for men and >7 drinks/week for women or binge drinking).13 A longitudinal study of 231 individuals with HIV infection found that those who frequently used alcohol (defined as ≥2 drinks daily) were 2.91 times more likely to have a decline in CD4+ cell count to below 200/μL (P= .015) independent of ART use over time, baseline CD4+ cell count, viral load, sex, age, and duration of HIV infection. Persons who frequently used alcohol while on ART had higher viral loads after controlling for sex, age, and CD4+ cell count than those who did not use or moderately used alcohol (P=.04).14

Alcohol use causes suppression of the innate and acquired immune systems that not only augments disease susceptibility but can also accelerate HIV progression.15 Additionally, alcohol disrupts the gut barrier, increases enteric microbial burden, and causes bacterial translocation, which exacerbates HIV disease progression.16 Nutrient deficiencies accelerate HIV progression, and alcohol is well known to cause nutrient, particularly micronutrient, deficiencies. Inadequate viral suppression is thought to be secondary to ineffective ART metabolism; the 2 proposed mechanisms are enzymatic inhibition from acute alcohol use competing with cytochrome p450 isozymes, and enzymatic induction from chronic alcohol use. Patients should be screened for high-risk alcohol use behaviors and extensively counseled on this modifiable risk factor.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

NAFLD constitutes a spectrum of disease encompassing nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), NASH, and advanced fibrosis or NASH cirrhosis. NAFL, otherwise known as simple steatosis, is the accumulation of steatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes, with or without mild lobular inflammation, in the absence of substantial alcohol intake.17 Steatosis is often macro- and microvesicular. Unlike alcoholic steatosis, microvesicular steatosis has a nonzonal distribution in the parenchyma, which can lead to higher grades of steatosis and progressive disease.18 Mild lobular inflammation with mononuclear cells, particularly lymphocytes, is typically found even in cases of simple steatosis.

The hallmark of NASH is the presence of ballooned hepatocytes, reflecting hepatocellular injury, which are required to make the diagnosis. Given the prognostic implications of differentiating NAFL from NASH in clinical trials, the NAFLD Activity Score (NAS; a histologic scoring system) was designed by pathologists to be a semiquantitative scoring system for defining NASH. The NAS focuses on scoring each of the following histologic changes: steatosis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocellular ballooning. An NAS of 5 or higher correlates with a diagnosis of NASH, and a score of below 3 indicates the absence of NASH.19 Notably, fibrosis is not included in the score. Steatosis, inflammation, and hepatocellular ballooning tend to be centrilobular in location. Without a clinical history, it can often be difficult to histologically differentiate NASH and ASH; however, certain features, such as presence of large Mallory-Denk bodies, canalicular cholestasis, chronic portal inflammation, and perivenular fibrosis, are observed more frequently in ASH than NASH.18 Unfortunately, no histologic features are pathognomonic to distinguish ALD from NAFLD, making a clinical history imperative.

NASH is a more severe and progressive subtype of NAFLD; therefore, more aggressive modification risk factors is warranted in individuals with NASH. Individuals with NASH are at not only at higher risk of liver-related mortality but also all-cause malignancy and, most of all, cardiovascular disease (13%–30%).20

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can occur in the absence of cirrhosis, a finding exemplified by the fact that cirrhosis was present in only 50% of participants in a multicenter study that compared NAFLD with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related HCC.21 This observation is concerning, as persons without cirrhosis are generally not undergoing HCC surveillance. Therefore, HCC can present with higher tumor burden due to delayed diagnosis.21 Ultimately, fibrosis stage and not NAS has been shown to be predictive of long-term mortality.22–24 In a large retrospective study examining participants over a period of 20 years, 12.1% of those with F3 fibrosis and 45% of those with F4 fibrosis developed decompensated liver disease.22

Although the prevalence of NAFLD in individuals with HIV infection varies depending on the study, a prospective biopsy-proven study found that 55% of individuals with chronically elevated liver enzymes had NASH, corroborating the importance of NAFLD screening in this patient population.7

The gold standard for distinguishing NASH from NAFL and assessing fibrosis stage is via liver biopsy. However, the inherent invasive nature, cost, and potential complications of liver biopsy preclude universal use. Alternative modalities for distinguishing NASH from NAFL include transient elastography (TE) with controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE), each of which have been well studied. MRE and transient elastography assess degree of fibrosis. The addition of CAP to transient elastography and proton density fat fraction (PDFF) to MRE allow for the measurement of steatosis.

A prospective cross-sectional study of more than 100 persons with biopsy-proven NAFLD compared the accuracy of TE to MRE for assessment of fibrosis and of CAP to magnetic resonance imaging-derived PDFF (MRI-PDFF) for assessment of steatosis.25 MRE was superior to transient elastography (AUROC, 0.82 vs 0.67) for diagnosing any stage of fibrosis and was significantly more accurate (P=.0116). However, no significant difference was found between the 2 modalities for diagnosing dichotomized stages of fibrosis. Notably, this study did use the extra-large (XL) probe during transient elastography, to account for high rates of obesity in the United States.25 MRI-PDFF was also superior to CAP (AUROC, 0.99 vs 0.85) in diagnosing any degree of steatosis, with significantly more accuracy (P= .0091), and in diagnosing dichotomized stages of steatosis (P=.0017 and P=.0238).25

The main limitations of MRE and MRI-PDFF are institutional availability, technical expertise required to perform and interpret results, cost, and claustrophobia for some patients.26 Therefore, some experts recommend that MRI-PDFF be considered mainly for individuals at high risk for NASH for whom an intervention is planned.26 Because of the acceptability of the AUROC for CAP in the study mentioned above and others plus the ability of transient elastography to rule out advanced fibrosis, transient elastography remains a viable option for most patients.

Etiologies

NAFLD Pathogenesis

There are many established risk factors for NAFLD, metabolic syndrome being primary. Metabolic syndrome encompasses hypertension, dyslipidemia (hypertriglyceridemia or low levels of high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol), increased waist circumference, and insulin resistance. Visceral adiposity and insulin resistance are well-studied driving forces of NAFLD with a complex interplay. In general, visceral adiposity contributes to worsening insulin resistance through excessive adipose tissue lipolysis, which can increase levels of free fatty acid and inflammatory cytokines plus decreased adipo-nectin levels, ultimately causing hepatotoxicity through mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress.27 Other comorbidities that have been linked to NAFLD include obstructive sleep apnea and polycystic ovarian syndrome.17,28

Genetic predisposition also plays a role in the development of NAFLD. The patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) rs738409 allele increases hepatic fat content and has been associated with elevated markers of hepatic inflammation. Notably, this allele has the highest frequency in the Hispanic population followed by the white and then African-American populations, making it a possible mechanism for racial disparities in prevalence of NAFLD.28 Additionally, there has been more evidence implicating the role of the gut microbiome in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Possible mechanisms include impairment of the gut barrier causing endotoxemia and activation of toll-like receptors, reduced choline bioavailability, increased short-chain fatty acids in obese adults, altered bile acid metabolism, and subsequent changes in farnesoid X receptor (FXR) signaling.29

HIV-Specific NAFLD

There are several proposed mechanisms leading to fatty liver disease in persons with HIV infection, including the traditional risk factors of metabolic syndrome (as mentioned above), hyperuricemia, HIV-related lipodystrophy, medications, HIV itself, and the gut microbiome (Box 1).

Box 1.

Risk Factors for HIV-Specific Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Metabolic syndrome (hypertension, dyslipidemia, increased waist circumference, insulin resistance)

HIV-related lipodystrophy

Hyperuricemia

Combination antiretroviral therapy

HIV virus

Gut microbiome

Metabolic syndrome has been shown to play a role in the development of fatty liver in individuals with HIV infection in some studies. Increased abdominal visceral adiposity (P <.001) and insulin resistance (P=.01) were independently associated with increased odds of fatty liver defined by computed tomography in participants with HIV infection in the MACS (Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study).30 The PNPLA3 rs738409 allele was independently associated with increased odds of fatty liver (P=.001).

In a retrospective study of individuals with HIV infection comparing those with biopsy-proven NASH with those who did not have NASH, body mass index, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and markers of insulin resistance were higher and HDL was lower in those with NASH. Participants with NASH had significantly higher frequency of 2 minor alleles for the PNPLA3 polymorphism (P<.004). Notably, participants with substantial fibrosis (measured as Ishak stage ≥2) tended to have concomitant NASH,7 defined by NAS.

A cross-sectional study in Italy assessing 225 individuals with HIV infection found that male sex and increased waist circumference were significantly associated (P<.001) with NAFLD in a multivariate logistic regression analysis.31 This study also assessed lipodystrophy through the respective anthropometric measurements. Although only 4.8% of the cohort was obese, a striking number had lipoatrophy (41%) and lipoatrophy with lipoaccumulation (38%). The presence of NAFLD in mostly nonobese, lipoatrophic men highlighted the possible link between NAFLD and HIV-associated body fat distribution.31

Fat misdistribution that occurs in the setting of HIV is known as HIV-related lipodystrophy and occurs frequently in long-term infected patients.32 Lipodystrophy is an umbrella term for lipoatrophy, lipoaccumulation, and a mixed syndrome of both. Lipoaccumulation is fat accumulation in areas such as the dorsocervical spine, abdomen, neck, and breasts. Lipoatrophy is loss of fat from regions such as the face, extremities, and buttocks. Patients will often present with a combination of lipoaccumulation and lipoatrophy. Lipodystrophy is thought to be a sequela of ART rather than HIV itself and has long-term cardiovascular implications, as it is associated with insulin resistance and dyslipidemia.33,34 Risk factors for lipodystrophy include older age, use of nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (nRTIs) and protease inhibitors (PIs), and total duration of ART.33 Given that worsening visceral adiposity has been linked to worsening insulin resistance, studies have demonstrated that persons with HIV infection and lipodystrophy had higher hepatic fat content (P <.05) measured by proton spectroscopy as well as features of insulin resistance.35

Outside of causing lipodystrophy, the role of ART in fatty liver continues to be investigated. It has been proposed that nRTIs can cause hepatic microvesicular steatosis by causing inhibition of mitochondrial DNA replication and overexpression of the sterol regulatory binding protein. nRTIs also cause hypertriglyceridemia, lipodystrophy, and hypoadiponectemia.30 Additionally, PIs promote insulin resistance and dyslipidemia.36 Longer cumulative ART exposure, nRTI exposure duration, lamivudine exposure, and dideoxynucleoside exposure were all significantly associated with fatty liver in a univariate analysis in the MACS.30 Conversely, a smaller study of 65 individuals with HIV infection found that neither NASH nor fibrosis was associated with duration of ART or specific antiretroviral drugs.7 Overall, the association between ART and fatty liver is likely driven by the adverse metabolic effects of ART, separate from the direct drug toxicity and hypersensitivity that can occur.6 Reports of ART exposure and fatty liver remain conflicting.

The role of HIV infection in causing fatty liver has also been controversial. In the MACS, presence of detectable HIV RNA (P=.66) and nadir CD4+ cell count (P=.69) were not associated with fatty liver. In a cross-sectional, case-control study conducted in China, HIV infection (P=.016) was associated with substantial liver fibrosis in a multivariate analysis. In a subset analysis of the participants with NAFL, 27% had substantial fibrosis (≥7 kPa; P=.014).37 Again, duration of disease, nadir or current CD4+ cell count, or prior AIDS were not associated with fatty liver.37

In a prospective study of 222 individuals with HIV/HCV coinfection, the strongest determinants of progression of hepatic steatosis between biopsies were alcohol use and high body mass index. In fact, effective ART was associated with reduced progression of steatosis.38

HIV may perpetuate fibrosis through infection of activated hepatic stellate cells (HSC), the principle fibrogenic cells in the liver. HIV can promote collagen I expression and secretion of proinflammatory chemokines. HIV and envelope glycoprotein gp120 can affect parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells, subsequently causing inflammation and fibrosis.39 Further, gp120 can cause an increase in HSC migration, which in turn increases secretion of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and expression of interleukin 6, each of which create a proinflammatory state and cause chronic inflammation and damage to surrounding hepatocytes. The action of gp120 on stellate cells is mediated through chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5). Studies in vivo found CCR5 expression at the sinusoidal level on inflammatory cells and the fibrotic septum,40 and CCR5 is now a pharma-cologic target. In individuals with HIV/HCV coinfection, gp120 can induce hepatocyte apoptosis through interactions with HCV proteins.41 Many of the mechanisms discussed above are particularly relevant in persons with HIV/HCV coinfection.

There is increasing evidence of the role of the gut microbiome on fatty liver disease. When bacteria translocate across the intestinal epithelial barrier, there are typically host mucosal immune barriers in place. However, when gut integrity is compromised, there are elevated markers of bacterial translocation such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS is a component of the cell walls of gram-negative bacteria. These heightened levels of LPS can lead to a state of deviant immune activation through a cascade that causes cytokine production. This becomes problematic in chronic disease processes such as HIV that lead to elevated circulating plasma LPS levels due to increased microbial translocation.42 HIV-associated microbial translocation occurs because in the setting of acute and even chronic infection, CD4+ cell depletion is more prevalent in the gut mucosa versus peripheral blood and lymph nodes, there- by leading to endothelial damage and exhaustion of intestinal macrophages. Subsequently, increased levels of LPS activate Kupffer cells, leading to release of profibrotic and proinflammatory cytokines and ultimately causing accelerated liver damage.16

Natural History Controversies

The estimated prevalence of NAFLD in individuals with HIV infection varies depending on the modality utilized to diagnose NAFLD but tends to be higher than in the general population; study estimates range from 30% to 40% based on imaging or transient elastography and up to 65% based on biopsy.3,36,43 The increased prevalence is likely related to the fact that prevalence of metabolic syndrome in individuals with HIV infection has doubled, from 19.4% in 2001 to 41.6% in 2007.44

In a cross-sectional, case-control study comparing individuals with HIV infection and NAFLD and individuals with primary NAFLD, those with HIV infection had higher rates of steatohepatitis (P=.04), corroborated by higher mean NAS (P=.00) and increased histologic features such as lobular inflammation and acidophil bodies (P <.001).45 Longer duration of HIV infection was associated with NASH (P=.004).45

A prospective cross-sectional study determined that coronary artery calcium score (CAC), a surrogate for coronary artery atherosclerosis, was associated with fatty liver disease in participants with HIV infection (median age, 43 years; odds ratio, 3.8; P <.01).46 However, CAC in the majority of participants was associated with a low or moderate Framingham risk score. Factors associated with CAC in participants with HIV infection included longer duration of HIV infection (median, 18 years; P <.01), lower CD4+ cell count nadir (P<.01), and current ART use (P <.01).46 With individuals with HIV infection living longer because of effective ART, the findings above underscore that those with HIV and NAFLD are not only at risk for more advanced liver disease but also cardiovascular disease associated with NAFLD. There are limited longitudinal studies assessing long-term outcomes in individuals with HIV infection with NAFLD, and it is an area that remains to be investigated.

Treatment Options

Current Therapies

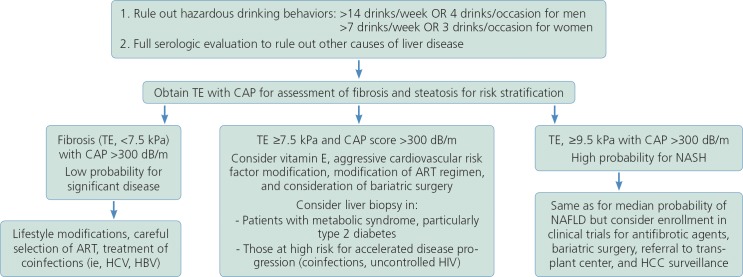

Lifestyle modifications are the corner stone of treatment for fatty liver disease, as there are limited pharmacologic therapies for NAFLD (Figure 2). Vigorous exercise alone, in the absence of weight loss, has demonstrated a decrease in the odds of developing NASH. Doubling the amount of time spent performing vigorous exercise resulted in decreased odds of advanced fibrosis.47

Figure 2.

Clinical suspicion of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease based on elevated liver-associated tests or abnormal ultrasound suggesting presence of fatty infiltration. TE indicates transient elastography; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; ART, antiretroviral therapy; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

A separate meta-analysis showed improvement in hepatic fat with exercise in the absence of weight loss.48 In terms of the effects of weight loss on NAFLD, 3% to 5% weight loss is associated with improvement in steatosis, weight loss of 7% or more is associated with improvement in steatohepatitis, and weight loss of 10% or more is associated with improvement in fibrosis and the highest likelihood of NASH resolution. In extreme cases, bariatric surgery can be considered and has led to improvement in NASH and fibrosis. Regarding dietary changes, a hypocaloric diet with goal weight loss of 0.5 to 1.0 kg per week is suggested.49

A major limitation of many of the currently available pharmacologic therapies for fatty liver disease is that they have not been studied in individuals with HIV infection. In nondiabetic persons, vitamin E 800 units daily led to notable improvement in NASH histology but not fibrosis. There have been some concerns regarding the association of vitamin E with prostate cancer. A randomized trial across the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico found that the risk of prostate cancer at a median follow-up of 7 years was increased by 17% in men taking 400 IU of vitamin E daily (hazard ratio [HR], 1.17; P= .008).50 However, in a randomized controlled trial of more than 14,000 men, taking vitamin E 400 IU every other day did not affect incidence of prostate cancer (HR, 0.99).51 The decision to treat with vitamin E should be individualized and discussed with the patient, taking into account the risk of cardiovascular disease with NASH compared with the potential risk of prostate cancer. Use of pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione, caused improvement in steatosis, lobular inflammation, and the NAS, but fell short of achieving the primary endpoint of improvement or resolution of NASH,52 and it does not improve fibrosis. Obeticholic acid, an FXR agonist, and pentoxifyilline, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, each demonstrated improvement in fibrosis along with improvement in NASH in a meta-analysis.53 Currently, vitamin E and pioglitazone are the mainstay of pharmacologic treatments for select persons with NASH. Neither has been studied in the HIV-infected population nor have obeticholic acid or pentoxifyilline.

Investigational Therapies

A multitude of phase II and III clinical trials are underway evaluating treatment for NAFLD. Therapies for NAFLD include peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists; stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) inhibitors; incretin-based agonists, such as glucagon-like peptide (GLP) agonists; tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors; those that target the gut microbiome; and most importantly, antifibrotic agents.54

PPAR agonists regulate several metabolic processes, including increasing fatty acid oxidation. Use of elafibrinor, a PPAR-α/σ agonist, led to significantly increased rates of NASH resolution and regression of fibrosis stage in a post hoc analysis with modified definitions for resolution of NASH and fibrosis progression from the initial analysis. Elafibrinor is currently in phase III clinical trials.55 SCD is an enzyme needed for synthesis of monosaturated fatty acids, and it has been shown that obese patients with NASH have higher SCD-1 activity. Aramachol is an SCD-1 inhibitor that led to decreased hepatic fat content, measured via magnetic resonance spectroscopy, when given over a period of 3 months.56 Notably, aramachol is currently being studied in the HIV-infected population.

GLP-1 has multiple metabolic roles, including augmenting peripheral insulin sensitivity. The LEAN study (Liraglutide Efficacy and Action in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis) found that liraglutide, a GLP-1 agonist, caused resolution of NASH and halted progression of fibrosis.57

Given that fibrosis predicts long-term mortality in NAFLD, there are several antifibrotic agents in clinical trials. Simtuzumab, a monoclonal antibody, was studied in persons with HIV or HCV infection or HIV/HCV coinfection in the setting of advanced liver disease but did not improve fibrosis or hepatic venous pressure gradient and is being investigated further.58 Galectin-3, an essential protein for fibrogenesis, is being targeted in a phase II clinical trial.54

Tesamorelin is a growth hormone-releasing hormone analogue initially approved for treatment of HIV-related lipodystrophy. However, it was found to improve serum ALT levels and hepatic fat content on magnetic resonance spectroscopy.59 There is a multicenter study in process to further investigate these preliminary results.2

Chemokine receptors (CCR2 and CCR5) are involved in the migration of inflammatory cells, and their respective chemokines have been found to upregulate in persons with NASH.60 A study evaluating 2 distinct cohorts proved that blockade of CCR5 leads to improvement in hepatic fibrosis, measured by Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Index after first validating with liver biopsy.61 Cenicriviroc, an oral dual CCR2 and CCR5 agonist, recently underwent a 1-year primary analysis with promising results. Although the primary outcome of NAS improvement was not significant, improvement in fibrosis was achieved in almost twice as many participants compared with placebo (20% vs 10%; P=.02).62

Other NAFLD treatment considerations in individuals with HIV infection include ART selection, because of the predilection for certain agents to cause insulin resistance, promoting alcohol abstinence, and treatment of coinfections such as HCV. If cirrhosis develops, liver transplantation should be considered barring any contraindications.

Conclusions

Fatty liver disease can be alcoholic or nonalcoholic in nature. Although there are subtle histologic differences, ALD and NAFLD must be distinguished based on clinical history. Alcohol use is prevalent among the HIV-infected population and can lead to nonadherence to ART, viral progression, and ineffectiveness of ART. NAFLD is a spectrum of disease ranging from simple steatosis (NAFL) to steatohepatitis (NASH) and subsequently to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. NAFLD is becoming a leading cause of liver transplantation in the United States. Persons with NASH are at higher risk of liver-related mortality, all-cause malignancy, and cardiovascular disease. Ultimately, fibrosis stage predicts long-term mortality.

Aminotransferase abnormalities in individuals with HIV infection are common, occurring in up to 60% of patients and clinicians should evaluate for NAFLD. As ART continues to improve and individuals with HIV infection are living longer, there has been a concerning rise in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and NAFLD in this population. Besides metabolic syndrome, there are numerous factors behind HIV-related NAFLD, including HIV-related lipodystrophy; ART, specifically older agents, nRTIs, and PIs; higher frequency of PNPLA3 polymorphisms; gut microbiome disturbances; and HIV infection itself. Persons with HIV infection tend to have more aggressive NAFLD in terms of higher rates of NASH and thus are at risk for liver- and cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality. For now, lifestyle modifications and perhaps careful consideration of ART are the mainstays of treatment in the HIV-infected population. Vitamin E and pioglitazone have not been studied in this population, but there are several promising agents in the pipeline in phase II and III clinical trials, namely antifibrotic agents.

Individuals with HIV infection with NAFLD should be closely monitored alongside pursuing more aggressive management of disease, as liver-related mortality is rising in this population. Major gaps in the literature include longitudinal outcomes studies of individuals with HIV infection with NAFLD, and further investigation is needed. Additionally, consensus on definitions used to categorize persons with ALD versus NAFLD is needed.

Footnotes

Financial affiliations in the past 12 months: Dr Sherman has received grant support or contracts awarded to his institution from AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Inc, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc, MedImmune, and Merck; served as an advisor or consultant to UniQure and Inovio Pharmaceuticals; and served on data and safety monitoring boards for Watermark and Medpace. Dr Seth has no relevant financial affiliations to disclose.

Contributor Information

Aradhna Seth, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Fellow.

Kenneth E. Sherman, Professor of Medicine at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine..

References

- 1. Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015; 148(3):547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tafesh ZH, Verna EC. Managing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients living with HIV. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017; 30(1):12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sterling RK, Smith PG, Brunt EM. Hepatic steatosis in human immunodeficiency virus: a prospective study in patients without viral hepatitis, diabetes, or alcohol abuse. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(2): 182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sherman K.E., Peters MG, Thomas D. Human immunodeficiency virus and liver disease: A comprehensive update. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1(10):987–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet. 2014; 384(9939):241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Price JC, Thio CL. Liver disease in the HIV-infected individual. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(12):1002–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morse CG, McLaughlin M, Matthews L, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatic fibrosis in HIV-1-monoinfected adults with elevated aminotransferase levels on antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(10):1569–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choi S, Diehl A. Alcoholic Liver Disease In: Friedman L, Martin P, eds. Handbook of Liver Disease. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Elsevier Inc.; 2017;109–120. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Teli MR, Day CP, Burt AD, Bennett MK, James OF. Determinants of progression to cirrhosis or fibrosis in pure alcoholic fatty liver. Lancet. 1995;346(8981):987–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zimmerman HJ. Serum enzymes in the diagnosis of hepatic disease. Gastroenterology. 1964;46:613–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Altamirano J, Miquel R, Katoonizadeh A, et al. A histologic scoring system for prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1231–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lackner C, Spindelboeck W, Haybaeck J, et al. Histological parameters and alcohol abstinence determine long-term prognosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2017;66(3):610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaudhry AA, Sulkowski MS, Chander G, Moore RD. Hazardous drinking is associated with an elevated aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index in an urban HIV-infected clinical cohort. HIV Med. 2009;10(3):133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, Sales S, Page JB, Campa A. Alcohol use accelerates HIV disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(5):511–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hahn JA, Samet JH. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Balagopal A, Philp FH, Astemborski J, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-related microbial translocation and progression of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2008; 135(1):226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015; 313(22):2263–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lackner C. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease In: Saxena R, ed. Practical Hepatic Pathology: A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Elsevier Inc.; 2017;167–187. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van NM, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41(6):1313–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pagadala MR, McCullough AJ. The relevance of liver histology to predicting clinically meaningful outcomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2012; 16(3):487–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piscaglia F, Svegliati-Baroni G, Barchetti A, et al. Clinical patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A multicenter prospective study. Hepatology. 2016;63(3):827–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hagstrom H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, et al. Fibrosis stage but not NASH predicts mortality and time to development of severe liver disease in biopsy-proven NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2017;67(6):1265–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ekstedt M, Hagstrom H, Nasr P, et al. Fi-brosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology. 2015;61(5):1547–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015; 149(2):389–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park CC, Nguyen P, Hernandez C, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography vs transient elastography in detection of fibrosis and noninvasive measurement of steatosis in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(3):598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dulai PS, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. MRI and MRE for non-invasive quantitative assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in NAFLD and NASH: clinical trials to clinical practice. J Hepatol. 2016;65(5):1006–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fabbrini E, Sullivan S, Klein S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology. 2010;51(2):679–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40(12):1461–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sharpton SR, Ajmera V, Loomba R. Emerging role of the gut microbiome in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from composition to function. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(2):296–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Price JC, Seaberg EC, Latanich R, et al. Risk factors for fatty liver in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(5):695–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guaraldi G, Squillace N, Stentarelli C, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in HIV-infected patients referred to a metabolic clinic: prevalence, characteristics, and predictors. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(2): 250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lichtenstein KA, Ward DJ, Moorman AC, et al. Clinical assessment of HIV-associated lipodystrophy in an ambulatory population. AIDS. 2001;15:1389–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carr A. HIV lipodystrophy: risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. AIDS. 2003;17 Suppl 1:S141-S148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lana LG, Junqueira DR, Perini E, Menezes de PC. Lipodystrophy among patients with HIV infection on antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sutinen J, Hakkinen AM, Westerbacka J, et al. Increased fat accumulation in the liver in HIV-infected patients with antiret-roviral therapy-associated lipodystrophy. AIDS. 2002;16(16):2183–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Pol S. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and HIV infection. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32(2):158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lui G, Wong VW, Wong GL, et al. Liver fibrosis and fatty liver in asian HIV-infected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(4):411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Woreta TA, Sutcliffe CG, Mehta SH, et al. Incidence and risk factors for steatosis progression in adults coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(3):809–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tuyama AC, Hong F, Saiman Y, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infects human hepatic stellate cells and promotes collagen I and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression: implications for the pathogenesis of HIV/hepatitis C virus-induced liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2010;52(2):612–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bruno R, Galastri S, Sacchi P, et al. gp120 modulates the biology of human hepatic stellate cells: a link between HIV infection and liver fibrogenesis. Gut. 2010; 59(4):513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blackard JT, Sherman KE. HCV/HIV coinfection: time to re-evaluate the role of HIV in the liver? J Viral Hepat. 2008;15(5): 323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marchetti G, Tincati C, Silvestri G. Microbial translocation in the pathogenesis of HIV infection and AIDS. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(1):2–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Macias J, Gonzalez J, Tural C, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with liver steatosis as measured by transient elastography with controlled attenuation parameter in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2014;28(9): 1279–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Worm SW, Friis-Moller N, Bruyand M, et al. High prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients: impact of different definitions of the metabolic syndrome. AIDS. 2010;24(3):427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vodkin I, Valasek MA, Bettencourt R, Cachay E, Loomba R. Clinical, biochemical and histological differences between HIV-associated NAFLD and primary NAFLD: a case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(4):368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Crum-Cianflone N, Krause D, Wessman D, et al. Fatty liver disease is associated with underlying cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected persons(∗). HIV Med. 2011; 12(8):463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kistler KD, Brunt EM, Clark JM, Diehl AM, Sallis JF, Schwimmer JB. Physical activity recommendations, exercise intensity, and histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106(3):460–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calza-dilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Eckel RH. Clinical practice. Nonsurgical management of obesity in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1941–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Klein EA, Thompson IM Jr., Tangen CM, et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2011; 306(14):1549–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang L, Sesso HD, Glynn RJ, et al. Vitamin E and C supplementation and risk of cancer in men: posttrial follow-up in the Physicians' Health Study II randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(3):915–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1675–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Singh S, Khera R, Allen AM, Murad MH, Loomba R. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2015;62(5):1417–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Oseini AM, Sanyal AJ. Therapies in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Liver Int. 2017;37 Suppl 1:97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ratziu V, Harrison SA, Francque S, et al. Elafibranor, an agonist of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and -delta, induces resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis without fibrosis worsening. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(5):1147–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Safadi R, Konikoff FM, Mahamid M, et al. The fatty acid-bile acid conjugate Aramchol reduces liver fat content in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(12):2085–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, et al. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2016;387(10019):679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Meissner EG, McLaughlin M, Matthews L, et al. Simtuzumab treatment of advanced liver fibrosis in HIV and HCV-infected adults: results of a 6-month open-label safety trial. Liver Int. 2016;36(12):1783–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stanley TL, Feldpausch MN, Oh J, et al. Effect of tesamorelin on visceral fat and liver fat in HIV-infected patients with abdominal fat accumulation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(4):380–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bertola A, Bonnafous S, Anty R, et al. Hepatic expression patterns of inflammatory and immune response genes associated with obesity and NASH in morbidly obese patients. PLoS One. 2010; 5(10):e13577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sherman KE, Abdel-Hameed E, Rouster SD, et al. Improvement in hepatic fibrosis biomarkers associated with chemokine receptor inactivation through mutation or therapeutic blockade. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;[epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Friedman SL, Ratziu V, Harrison SA, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of cenicriviroc for treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with fibrosis. Hepatology. 2018;67(5):1754–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]