Abstract

Objective

To examine whether the KLOTHO gene variant KL-VS attenuates APOE4-associated β-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation in a late-middle-aged cohort enriched with Alzheimer disease (AD) risk factors.

Methods

Three hundred nine late-middle-aged adults from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention and the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center were genotyped to determine KL-VS and APOE4 status and underwent CSF sampling (n = 238) and/or 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB)-PET imaging (n = 183). Covariate-adjusted regression analyses were used to investigate whether APOE4 exerted expected effects on Aβ burden. Follow-up regression analyses stratified by KL-VS genotype (i.e., noncarrier vs heterozygous; there were no homozygous individuals) evaluated whether the influence of APOE4 on Aβ was different among KL-VS heterozygotes compared to noncarriers.

Results

APOE4 carriers exhibited greater Aβ burden than APOE4-negative participants. This effect was stronger in CSF (t = −5.12, p < 0.001) compared with PiB-PET (t = 3.93, p < 0.001). In the stratified analyses, this APOE4 effect on Aβ load was recapitulated among KL-VS noncarriers (CSF: t = −5.09, p < 0.001; PiB-PET: t = 3.77, p < 0 .001). In contrast, among KL-VS heterozygotes, APOE4-positive individuals did not exhibit higher Aβ burden than APOE4-negative individuals (CSF: t = −1.03, p = 0.308; PiB-PET: t = 0.92, p = 0.363). These differential APOE4 effects remained after KL-VS heterozygotes and noncarriers were matched on age and sex.

Conclusion

In a cohort of at-risk late-middle-aged adults, KL-VS heterozygosity was associated with an abatement of APOE4-associated Aβ aggregation, suggesting KL-VS heterozygosity confers protections against APOE4-linked pathways to disease onset in AD.

After aging, the greatest risk factor for developing late-onset Alzheimer disease (AD) is the presence of ≥1 copies of APOE4.1,2 This genetic variant is overrepresented among persons with AD compared with the general population3 and is associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline4 and an earlier age at dementia onset5 among persons with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Even among cognitively normal adults, APOE4 carriers exhibit comparatively greater cerebral β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition,6,7 poorer performance on cognitive tests,8 accelerated rate of cognitive decline,9 and higher likelihood of a future diagnosis of MCI or AD dementia.10 Overall, evidence suggests that a major pathophysiologic phenotype of APOE4 is an increase in cerebral Aβ deposition.11

Klotho is a transmembrane protein and longevity factor12,13 that increases neural functions and brain resilience.14–16 It circulates throughout the body and brain to regulate myriad pathways, including insulin,13 fibroblast growth factor,17 and NMDA receptor14–16 signaling. In humans, the KLOTHO gene variants F352V and C370S segregate together to form a haplotype (KL-VS) that modulates klotho secretion.14,18 Carrying 1, but not 2, copies of the KL-VS haplotype increases systemic klotho levels,14,19 promotes longevity and resilience against age-induced disease,18,20,21 and is linked to enhanced cognition,15 greater cortical volumes,19,22 and increased brain connectivity23 in aging humans.

KL-VS has been associated with better brain health among those aging normally but has not been extensively examined in those at high risk for developing neurodegenerative disease. Thus, it remains unknown whether positive links with the KLOTHO variant potentially extend to neurodegenerative disease. In light of this gap, we probed whether KL-VS exerts an effect on APOE4-induced aggregation of cerebral Aβ among late-middle-aged adults at risk for AD. We determined Aβ burden using both CSF sampling and 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) PET.24 Because previous studies have demonstrated that KL-VS heterozygosity has a protective effect,14,18 we predicted that the prototypical APOE4-related increase in Aβ load would be attenuated among KL-VS heterozygotes.

Methods

Participants

Three hundred nine late-middle-aged adults from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention25 and the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center participated in this study. They were diagnostically characterized as cognitively normal in standardized, multidisciplinary, consensus conferences on the basis of intact performance on a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests, absence of functional impairment, and absence of neurologic/psychiatric conditions that might impair cognition.26,27 These individuals were selected for the present analyses on the basis of having undergone genotyping for KLOTHO and APOE, as well as having had either a PiB-PET examination or lumbar puncture assessing CSF Aβ42. Specifically, of the 309 participants, 112 had both CSF and PiB-PET data, 126 had CSF but not PiB-PET data, and 71 had PiB-PET but not CSF data. Thus, the CSF analyses presented in this report included 238 participants (i.e., 112 + 126), whereas the PiB-PET analyses included 183 participants (i.e., 112 + 71).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, and each participant provided signed informed consent before participation.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from whole-blood samples with the PUREGENE DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, MN). DNA concentrations were quantified with ultraviolet spectrophotometry (DU 530 Spectrophotometer, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Single nucleotide polymorphisms for APOE (rs429358 and rs7412) and KLOTHO (rs9536314 for F352V and rs9527025 for C370S) were genotyped by LGC Genomics (Beverly, MA) using competitive allele-specific PCR-based KASP genotyping assays. As expected from HapMap and previous work,14,19,20 rs9536314 and rs9527025 were in perfect linkage disequilibrium. Quality control (e.g., duplicate sample concordance rates and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium) has been previously described7 and was found to be satisfactory.

CSF assessment

Lumbar puncture for collection of CSF samples was performed in the morning after a 12-hour fast with a Sprotte 24- or 25-gauge spinal needle at L3-4 or L4-5 with gentle extraction into polypropylene syringes. Each sample consisted of 22 mL CSF, which was then combined, gently mixed, and centrifuged at 2,000g for 10 minutes. Supernatants were frozen in 0.5-mL aliquots in polypropylene tubes and stored at −80°C. The samples were immunoassayed for Aβ42 with INNOTEST ELISAs (Fujirebio, Gent, Belgium) by board-certified laboratory technicians who were blinded to clinical data and used protocols accredited by the Swedish Board for Accreditation and Conformity Assessment, as previously described.28

PiB-PET protocol

Details on the acquisition and postprocessing of the PiB-PET examinations have been previously described.26 Briefly, 3-dimensional PiB-PET data were acquired on a Siemens EXACT HR+ scanner (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). Imaging consisted of a 6-minute transmission scan and a 70-minute dynamic scan on bolus injection. Postprocessing was based on an in-house automated pipeline.29 We derived distribution volume ratio (DVR) maps from the PiB images using the Logan method, with a cerebellar gray matter reference.30 An anatomic atlas31 was used to extract mean quantitative DVR data from 8 bilateral regions of interest (ROIs) that are sensitive to Aβ accumulation.32,33 These ROIs were the angular gyrus, anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, medial orbitofrontal cortex, precuneus, supramarginal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and superior temporal gyrus. The DVR data from the ROIs were also combined to form a composite measure of global Aβ burden.

Statistical analyses

We first ascertained that APOE4 indeed exerts the expected effect on Aβ load within our relatively young sample by fitting a series of linear regression models that included terms for APOE4, age, sex, and parental history of AD. Then, to determine whether the APOE4 effect was differentially instantiated as a function of KL-VS heterozygosity, we refitted the original model but this time stratified the sample by KL-VS genotype (i.e., fitting separate models for KL-VS noncarriers and KL-VS heterozygotes; there were no KL-VS homozygotes).34 All analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS, version 21.0 (Armonk, NY). CSF Aβ42 and the PiB composite were our primary outcomes and were evaluated at an unadjusted α of 0.05 (2 tailed). The ROI components of the PiB composite were secondary outcomes and were evaluated at a familywise error rate–adjusted α of 0.05 (2 tailed) using the Holm35-Bonferroni procedure.

Data availability statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator to the corresponding author for purposes of replicating procedures and results.

Results

Background characteristics

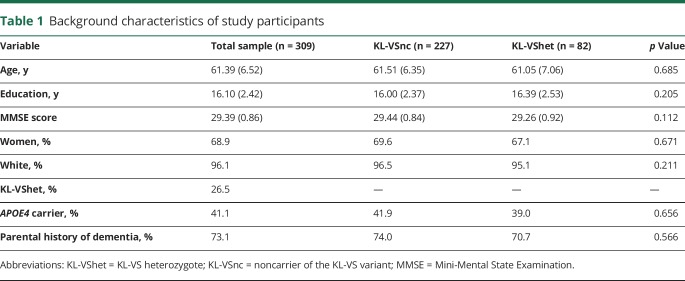

Table 1 details background characteristics of the participants for the overall sample and stratified by KL-VS genotype. The average age was 61.39 ± 6.52 years, and 68.9% were women. The average education was 16.10 ± 2.42 years; the mean Mini Mental State Examination score was 29.39 ± 0.86; 41.1% of participants were APOE4 carriers; and 73.1% had a parental history of dementia. Similar to prior studies,14,19,20 KL-VS heterozygotes represented 27% of the sample. There were no KL-VS homozygotes in our sample, which is an expected finding considering the allele frequency.14 KL-VS noncarriers did not differ significantly from KL-VS heterozygotes on any of these background characteristics.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of study participants

Association between APOE4 and Aβ burden

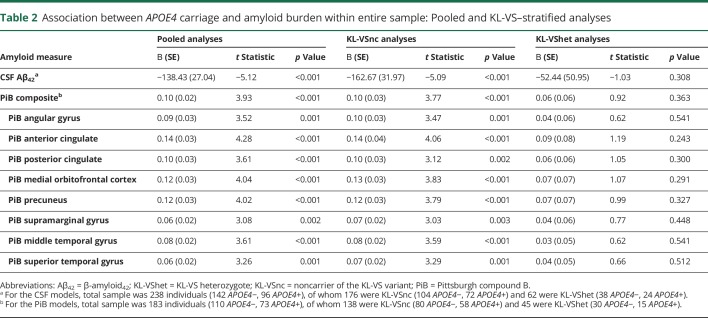

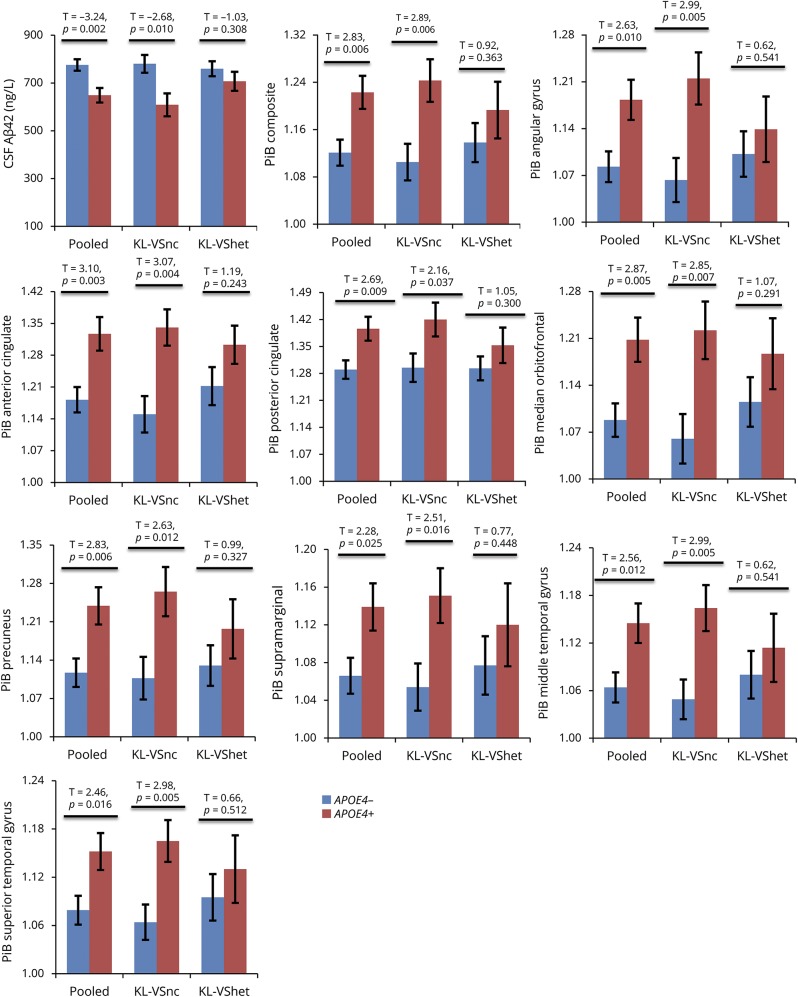

As expected, APOE4 was significantly associated with Aβ load in both CSF and brain platforms, with APOE4 carriers exhibiting lower CSF Aβ42 and higher PiB-PET binding compared with those who were APOE4 negative (table 2, second column). These findings are depicted graphically in figure 1. This APOE4 effect was numerically stronger in CSF (R2 = 0.11, t = −5.12) compared with PiB-PET (largest R2 [anterior cingulate] = 0.08, t = 4.28).

Table 2.

Association between APOE4 carriage and amyloid burden within entire sample: Pooled and KL-VS–stratified analyses

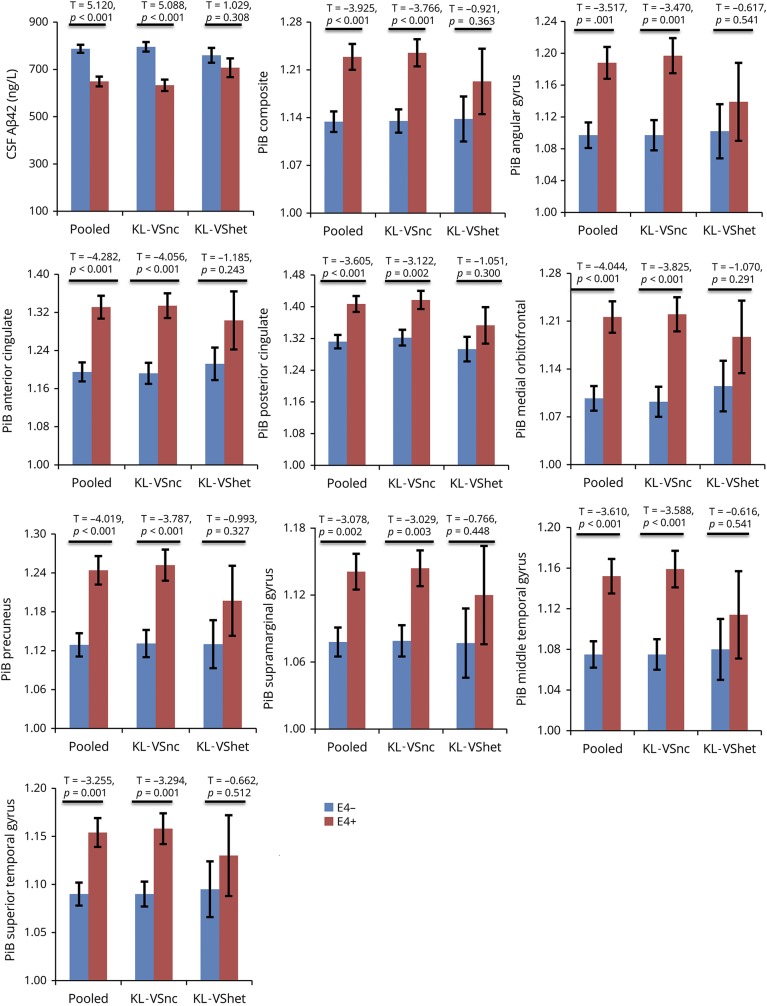

Figure 1. APOE4 differentially associates with amyloid burden as a function of KL-VS status (whole-sample analyses).

Bar graphs depicting group differences in amyloid between APOE4− (blue bars) and APOE4+ individuals (red bars). Analyses were performed using all participants with available data. Specifically, for the CSF graph, total (i.e., pooled) sample was 238 individuals (142 APOE4−, 96 APOE4+), of whom 176 were noncarriers of the KL-VS variant (KL-VSnc) (104 APOE4−, 72 APOE4+) and 62 were KL-VS heterozygotes (KL-VShet) (38 APOE4−, 24 APOE4+). For the Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) graphs, total sample was 183 individuals (110 APOE4−, 73 APOE4+), of whom 138 were KL-VSnc (80 APOE4−, 58 APOE4+) and 45 were KL-VShet (30 APOE4−, 15 APOE4+). Aβ42 = β-amyloid42.

APOE4-related alteration in aβ burden varies by KL-VS status

Table 2 presents results of the KL-VS–stratified analyses. Among KL-VS noncarriers, APOE4 carriers consistently exhibited lower CSF Aβ42 values and higher PiB-PET retention compared with APOE4 noncarriers (table 2, third column). In contrast, among KL-VS heterozygotes, APOE4 carriers did not differ from APOE4 noncarriers in either CSF Aβ42 levels or PiB-PET retention (table 2, fourth column). The percent attenuation in the APOE4 effect among KL-VS heterozygotes vis-à-vis KL-VS noncarriers ranged from 40% to 63% (table 2, last column). These findings are depicted in figure 1.

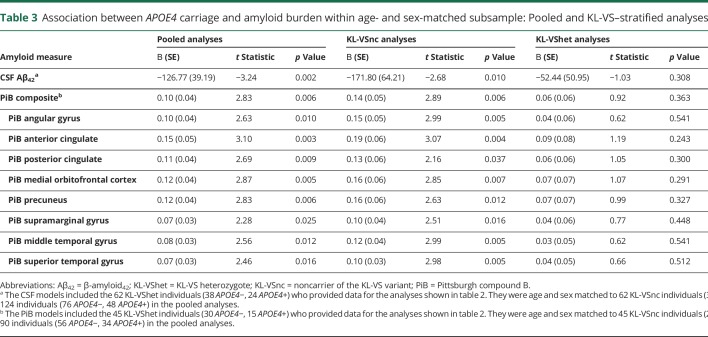

Because there were considerably more KL-VS noncarriers than KL-VS heterozygotes (176 vs 62 for CSF analyses, 138 vs 45 for PiB-PET analyses; see table 2 footnote), there is the possibility that the differential effect of APOE4 within KL-VS noncarriers vs KL-VS heterozygotes might simply be due to this differing sample sizes. To exclude this possibility, the CSF analyses reported in table 2 were repeated after the 62 KL-VS heterozygotes with CSF data were age and sex matched to 62 KL-VS noncarriers (mean ± SD age 61.22 ± 7.71 vs 61.30 ± 8.27 years, respectively, p = 0.956; female 66.1% vs 64.5%, p = 0.850). Similarly, the PiB-PET analyses shown in table 2 were repeated after the 45 KL-VS heterozygotes with PiB-PET data were age and sex matched to 45 KL-VS noncarriers (mean ± SD age 61.05 ± 7.06 vs 61.09 ± 7.12, respectively, p = 0.979; female 62.2% vs 62.2%, p = 1.00).

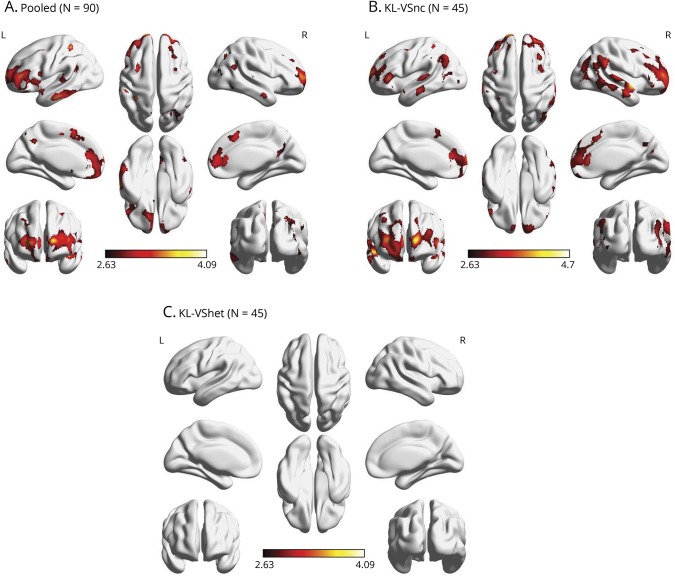

As in the full-sample analyses, the matched-sample analyses revealed that, for KL-VS noncarriers, APOE4 carriage was consistently associated with lower CSF Aβ42 values and higher PiB-PET retention (table 3, third column), which was not the case for KL-VS heterozygotes (table 3, fourth column). In this matched sample, the percent attenuation in the APOE4 effect among KL-VS heterozygotes vis-à-vis KL-VS noncarriers ranged from 53% to 75% (table 3, last column). These findings are also shown in figure 2.

Table 3.

Association between APOE4 carriage and amyloid burden within age- and sex-matched subsample: Pooled and KL-VS–stratified analyses

Figure 2. APOE4 differentially associates with amyloid burden as a function of KL-VS status (matched-sample analyses).

Bar graphs depicting group differences in amyloid between APOE4− (blue bars) and APOE4+ (red bars) individuals. Analyses were performed among age- and sex-matched participants. Specifically, the CSF graph included the 62 KL-VS heterozygote (KL-VShet) individuals (38 APOE4−, 24 APOE4+) who provided data for the results shown in figure 1. They were age and sex matched to 62 noncarriers of the KL-VS variant (KL-VSnc) (38 APOE4−, 24 APOE4+) for a total (i.e., pooled) sample of 124 individuals (76 APOE4−, 48 APOE4+). The Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) graphs included the 45 KL-VShet individuals (30 APOE4−, 15 APOE4+) who provided data for the results shown in figure 1. They were age and sex matched to 45 KL-VSnc individuals (26 APOE4−, 19 APOE4+) for a total sample of 90 individuals (56 APOE4−, 34 APOE4+). Aβ42 = β-amyloid42.

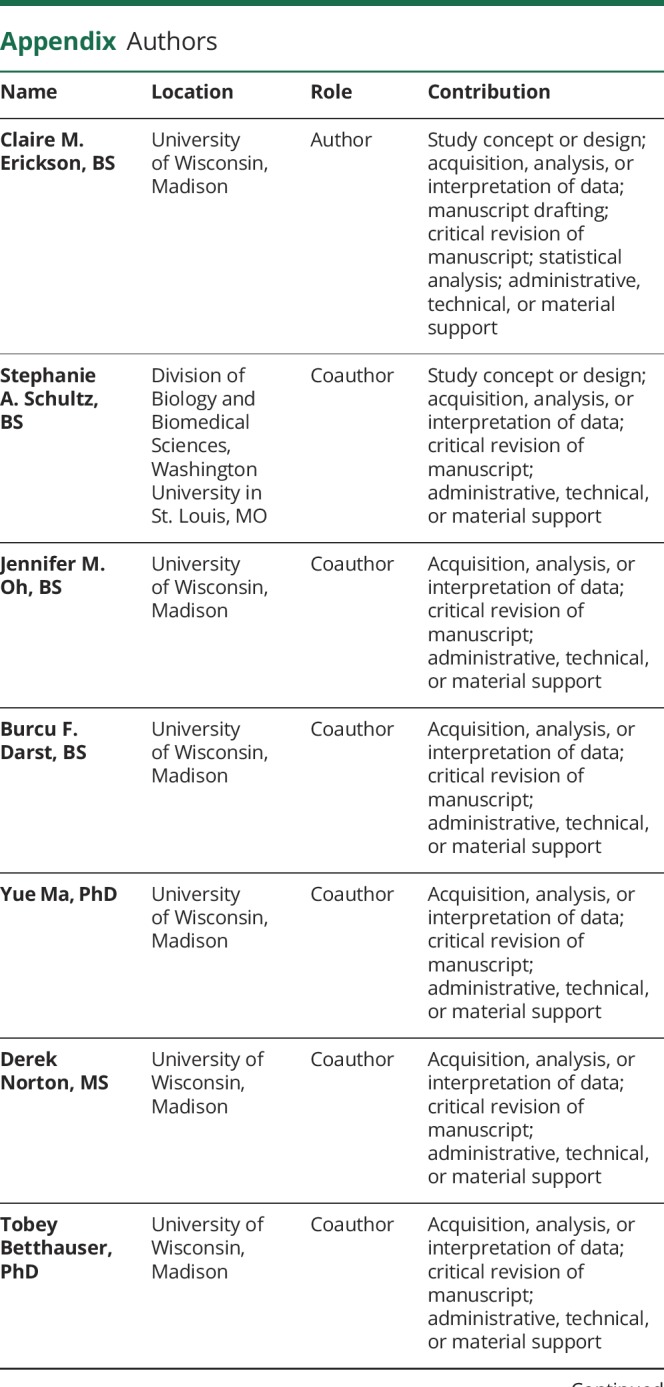

To delineate the spatial reach of the PiB-PET findings on a whole-brain level, we implemented exploratory voxel-wise regression analyses in SPM8 (fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) within the matched sample (n = 90) while imposing a pvoxel < 0.005 uncorrected threshold and a cluster size minimum of 100 contiguous voxels for statistical significance. The analysis adjusted for the same covariates as in the ROI models. We found that, within the entire matched sample, APOE4 carriage was significantly associated with greater Aβ burden in several brain regions, including right posterior cingulate, right middle temporal gyrus, right superior temporal gyrus, right superior frontal gyrus, left inferior temporal gyrus, bilateral inferior frontal gyrus, bilateral anterior cingulate, bilateral inferior parietal lobule, bilateral precuneus, and bilateral middle frontal gyrus (figure 3A). With stratification by KL-VS genotype, these findings were reproduced among KL-VS noncarriers with remarkable similarity (figure 3B). On the other hand, we did not detect any APOE4 effects among KL-VS heterozygotes at the set threshold (figure 3C).

Figure 3. Spatial representation of APOE4–amyloid burden relationship as a function of KL-VS status (tested within age- and sex-matched subsample).

A 3-dimensional rendering of the effect of APOE4 carriership on cerebral amyloid among (A) a pooled sample of 90 participants comprising 45 KL-VS heterozygote (KL-VShet) individuals who were age and sex matched to 45 noncarriers of the KL-VS variant (KL-VSnc), (B) the 45 KL-VSnc individuals, and (C) the 45 KL-VShet individuals. Results were thresholded at pvoxel < 0.005 and a minimum of 100 contiguous voxels on the basis of Monte Carlo simulations (3dClustSim, AFNI, afni.nimh.nih.gov).

Direct effects of KL-VS on Aβ deposition

Although not a distinct aim of the study, we exploratorily examined whether KL-VS status is directly associated with Aβ burden. We ran these analyses in both the full sample (n = 183 for PiB, n = 238 for CSF Aβ42) and the age- and sex-matched sample (n = 90 for PiB, n = 124 for CSF Aβ42). For completeness sake, we additionally stratified by APOE4 status. The only effect detected was of KL-VS on CSF Aβ42 among APOE4 carriers within the age- and sex-matched sample. Specifically, KL-VS heterozygotes in this subsample had higher Aβ42 (714.81 ± 44.22) compared with KL-VS noncarriers (582.44 ± 44.22; p = 0.049).

Discussion

This study showed that, in a late-middle-aged cohort at risk for AD, KL-VS heterozygosity attenuates APOE4 effects on Aβ burden, assessed with both PET imaging and CSF analyses. The relationship between KLOTHO and APOE4 status has not been extensively investigated in humans. These data suggest that beneficial effects of the longevity factor klotho in the brain may mitigate deleterious mechanisms linked to APOE4. Furthermore, in line with previous findings, this study observed the well-described relationship between APOE4 status and increased Aβ burden, even though our participants were relatively young (mean age 61 years).

APOE4 carriage has long been established as the most potent genetic risk factor for late-onset AD. Initial studies found that it exerted a strong gene dose effect on prevalence of AD.5,36,37 Specifically, in a large case-control study, the distribution of cases diagnosed with AD at age 75 years was 24% among APOE4 noncarriers, 61% among APOE4 heterozygotes, and 86% among APOE4 homozygotes.5 The same study found that, relative to APOE4 noncarriers, APOE4 heterozygotes were at 2.8-fold increased hazard for developing AD, whereas APOE4 homozygotes were at an 8.1-fold higher hazard for the disease.5 Building on prior in vitro findings of a role for the ApoE protein in Aβ metabolism,38 later in vivo studies demonstrated that, of the pathologic features of AD, APOE4 was selectively linked to an increase in cerebral Aβ deposition.3,39,40 In the current study, we similarly found that middle-aged adults who were APOE4 carriers had increased cerebral Aβ and reduced CSF Aβ42 compared with APOE4 noncarriers.41 We also found that this APOE4 differential was more pronounced in CSF relative to PET imaging, suggesting a comparatively higher sensitivity of CSF Aβ42 vis-à-vis PiB-PET to cerebral amyloidosis in this preclinical stage.7,42–44 This finding corroborates prior studies suggesting that CSF-derived measures of β-amyloidosis are more sensitive to underlying AD pathology than neuroimaging-based measures.42–44

The KL-VS allele of the longevity gene KLOTHO has been associated with positive brain and cognitive health during normal human aging in a recent series of studies.14,18,20,21 One such study14 found that, in 3 separate cohorts of cognitively healthy adults, KL-VS heterozygotes had enhanced global cognition compared to KL-VS noncarriers. The average effect size of this enhancement across cohorts was a Cohen d of 0.34,14 which exceeded the effect size of APOE4 of 0.27 in similar healthy aging cohorts.45 In 2 independent studies,19,22 KL-VS heterozygosity was associated with greater volume in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and better executive function,19 as well as slower cognitive decline.22 There is also evidence that KL-VS heterozygosity resulted in higher serum klotho, which, in turn, predicted greater intrinsic connectivity in key cortical hubs such as the default mode network.23 Even so, it should be noted that beneficial effects of KL-VS were not observed in other populations at particularly advanced ages.46,47 The culmination of these studies is that KL-VS heterozygosity largely wields a salutary influence on brain aging. In this study, we extend prior reports by showing that KL-VS heterozygosity abates the potent effect of APOE4 carriage on Aβ burden in those at risk for AD.

This study demonstrates that the KLOTHO variant KL-VS is associated with attenuation of a key pathogenic protein and biomarker of neurodegenerative disease. It is interesting to speculate that, since the klotho protein is a longevity factor, its protective effects could relate to mechanisms that delay aging itself.14 Alternatively, klotho effects could be related directly or indirectly to the ApoE protein and its known effects on Aβ aggregation and clearance.48–50 Whether klotho and ApoE interact directly or indirectly and whether klotho blocks ApoE-induced mechanisms should be determined. In addition to the prognostic implications of carrying the KL-VS gene variant of KLOTHO, these data suggest that KLOTHO pathways may counter deleterious effects of APOE4 in aging and disease.

A limitation to our study is the demographic composition. Participants were mostly highly educated and white, thus potentially limiting the generalizability of our study findings. Another limitation is the relatively high prevalence of APOE4 carriership within the cohort compared to the general population. In addition, given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we do not know whether KL-VS heterozygosity modifies APOE4-related trajectories in prospective cognitive course or in the attainment of clinically relevant endpoints of MCI/dementia. Because we are following up the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention/Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center cohorts prospectively, we will be well positioned to tackle this important question in the future.

Our key finding is that KL-VS heterozygosity attenuates the effect of APOE4 on Aβ deposition, suggesting that KL-VS heterozygosity potentially alters APOE4-associated differences in disease pathology, thus conferring resilience to APOE4-linked pathways to disease onset in AD.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the researchers and staff of the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, where the CSF assays took place. They thank the staff and study participants of the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention and the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, without whom this work would not be possible.

Glossary

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- DVR

distribution volume ratio

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- PiB

11C-Pittsburgh compound B

- ROI

region of interest

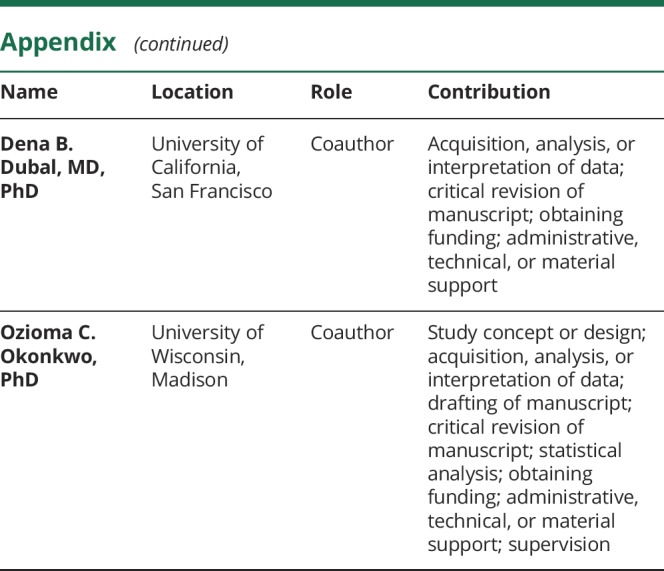

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Comment Longevity gene KLOTHO may play a role in Alzheimer disease Page 751

Study funding

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging grants K23 AG045957 (O.C.O.), R21 AG051858 (O.C.O.), R01 AG027161 (S.C.J.), R01 AG021155 (S.C.J.), R01 AG054047 (C.D.E.), R01 AG037639 (B.B.B.), and P50 AG033514 (S.A.); by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R01 NS092918 (D.B.D.); and a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR025011) to the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Portions of this research were supported by the Extendicare Foundation; Alzheimer's Association; Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation; Veterans Administration, including facilities and resources at the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, WI; Swedish Research Council; European Research Council; Torsten Söderberg Foundation; Swedish Brain Foundation; and Wallenberg Academy.

Disclosure

C. Erickson, S. Schultz, J. Oh, B. Darst, Y. Ma, D. Norton, T. Betthauser, C. Gallagher, C. Carlsson, B. Bendlin, S. Asthana, B. Hermann, and M. Sager report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. K. Blennow has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for Alzheon, BioArctic, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Fujirebio Europe, IBL International, Pfizer, and Roche Diagnostics and is a cofounder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB, a GU Ventures–based platform company at the University of Gothenburg. H. Zetterberg has served at advisory board for Eli Lilly, Roche Diagnostics, and Wave; has received travel support from Teva; and is cofounder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB, a GU Ventures–based platform company at the University of Gothenburg. C. Engelman and B. Christian report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. S. Johnson has served on an advisory board for Roche Diagnostics. D. Dubal has served as a consultant for Unity Biotechnology. Klotho is the subject of a pending international patent application held by the Regents of the University of California. O. Okonkwo reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Roses AD. Apolipoprotein E alleles as risk factors in Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Med 1996;47:387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brousseau T, Legrain S, Berr C, Gourlet V, Vidal O, Amouyel P. Confirmation of the epsilon 4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene as a risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1994;44:342–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polvikoski T, Sulkava R, Haltia M, et al. Apolipoprotein E, dementia, and cortical deposition of β-amyloid protein. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1242–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosentino S, Scarmeas N, Helzner E, et al. APOE ε4 allele predicts faster cognitive decline in mild Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 2008;70:1842–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science 1993;261:921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlassenko AG, Mintun MA, Xiong C, et al. Amyloid-beta plaque growth in cognitively normal adults: longitudinal [11C]Pittsburgh compound B data. Ann Neurol 2011;70:857–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darst BF, Koscik RL, Racine AM, et al. Pathway-specific polygenic risk scores as predictors of amyloid-beta deposition and cognitive function in a sample at increased risk for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;55:473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantarci K, Lowe V, Przybelski SA, et al. APOE modifies the association between Abeta load and cognition in cognitively normal older adults. Neurology 2012;78:232–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caselli RJ, Graff-Radford NR, Reiman EM, et al. Preclinical memory decline in cognitively normal apolipoprotein E-ε4 homozygotes. Neurology 1999;53:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bookheimer S, Burggren A. APOE-4 genotype and neurophysiological vulnerability to Alzheimer's and cognitive aging. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2009;5:343–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu CC, Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol 2013;9:106–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Château MT, Araiz C, Descamps S, Galas S. Klotho interferes with a novel FGF-signalling pathway and insulin/Igf-like signalling to improve longevity and stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging 2010;2:567–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, et al. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science 2005;309:1829–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubal DB, Yokoyama JS, Zhu L, et al. Life extension factor klotho enhances cognition. Cell Rep 2014;7:1065–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubal DB, Zhu L, Sanchez PE, et al. Life extension factor klotho prevents mortality and enhances cognition in hAPP transgenic mice. J Neurosci 2015;35:2358–2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leon J, Moreno AJ, Garay BI, et al. Peripheral elevation of a Klotho fragment enhances brain function and resilience in young, aging, and alpha-synuclein transgenic mice. Cell Rep 2017;20:1360–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurosu H, Kuro-o M. The Klotho gene family and the endocrine fibroblast growth factors. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2008;17:368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arking DE, Krebsova A, Macek M, et al. Association of human aging with a functional variant of klotho. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:856–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yokoyama JS, Sturm VE, Bonham LW, et al. Variation in longevity gene KLOTHO is associated with greater cortical volumes. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2015;2:215–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arking DE, Atzmon G, Arking A, Barzilai N, Dietz HC. Association between a functional variant of the KLOTHO gene and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure, stroke, and longevity. Circ Res 2005;96:412–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Invidia L, Salvioli S, Altilia S, et al. The frequency of Klotho KL-VS polymorphism in a large Italian population, from young subjects to centenarians, suggests the presence of specific time windows for its effect. Biogerontology 2010;11:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Vries CF, Staff RT, Harris SE, et al. Klotho, APOEepsilon4, cognitive ability, brain size, atrophy, and survival: a study in the Aberdeen Birth Cohort of 1936. Neurobiol Aging 2017;55:91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yokoyama JS, Marx G, Brown JA, et al. Systemic klotho is associated with KLOTHO variation and predicts intrinsic cortical connectivity in healthy human aging. Brain Imaging Behav 2017;11:391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer's disease with Pittsburgh compound-B. Ann Neurol 2004;55:306–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson SC, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, et al. The Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention: a review of findings and current directions. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2018;10:130–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okonkwo OC, Schultz SA, Oh JM, et al. Physical activity attenuates age-related biomarker alterations in preclinical AD. Neurology 2014;83:1753–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almeida RP, Schultz SA, Austin BP, et al. Effect of cognitive reserve on age-related changes in cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmqvist S, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, et al. Accuracy of brain amyloid detection in clinical practice using cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 42: a cross-validation study against amyloid positron emission tomography. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:1282–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Floberg JM, Mistretta CA, Weichert JP, Hall LT, Holden JE, Christian BT. Improved kinetic analysis of dynamic PET data with optimized HYPR-LR. Med Phys 2012;39:3319–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price JC, Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, et al. Kinetic modeling of amyloid binding in humans using PET imaging and Pittsburgh compound-B. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2005;25:1528–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage 2002;15:273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosario BL, Weissfeld LA, Laymon CM, et al. Inter-rater reliability of manual and automated region-of-interest delineation for PiB PET. Neuroimage 2011;55:933–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark LR, Racine AM, Koscik RL, et al. Beta-amyloid and cognitive decline in late middle age: findings from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention study. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12:805–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Behrens G, Winkler TW, Gorski M, Leitzmann MF, Heid IM. To stratify or not to stratify: power considerations for population-based genome-wide association studies of quantitative traits. Genet Epidemiol 2011;35:867–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holm S. A simple sequential rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saunders AM, Schmader K, Breitner JC, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele distributions in late-onset Alzheimer's disease and in other amyloid-forming diseases. Lancet 1993;342:710–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1993;43:1467–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wisniewski T, Frangione B. Apolipoprotein E: a pathological chaperone protein in patients with cerebral and systemic amyloid. Neurosci Lett 1992;135:235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmechel DE, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, et al. Increased amyloid beta-peptide deposition in cerebral cortex as a consequence of apolipoprotein E genotype in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993;90:9649–9653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farfel JM, Yu L, De Jager PL, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Association of APOE with tau-tangle pathology with and without beta-amyloid. Neurobiol Aging 2016;37:19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann Neurol 2006;59:512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landau SM, Lu M, Joshi AD, et al. Comparing positron emission tomography imaging and cerebrospinal fluid measurements of beta-amyloid. Ann Neurol 2013;74:826–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mattsson N, Insel PS, Donohue M, et al. Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging I: independent information from cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta and florbetapir imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2015;138:772–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schultz SA, Boots EA, Almeida RP, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness attenuates the influence of amyloid on cognition. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2015;21:841–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deary IJ, Whiteman MC, Pattie A, et al. Cognitive change and the APOE epsilon 4 allele. Nature 2002;418:932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Almeida OP, Morar B, Hankey GJ, et al. Longevity Klotho gene polymorphism and the risk of dementia in older men. Maturitas 2017;101:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mengel-From J, Soerensen M, Nygaard M, McGue M, Christensen K, Christiansen L. Genetic variants in KLOTHO associate with cognitive function in the oldest old group. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71:1151–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung WS, Verghese PB, Chakraborty C, et al. Novel allele-dependent role for APOE in controlling the rate of synapse pruning by astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:10186–10191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 2009;63:287–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang YA, Zhou B, Wernig M, Sudhof TC. ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4 differentially stimulate APP transcription and Abeta secretion. Cell 2017;168:427–441.e421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator to the corresponding author for purposes of replicating procedures and results.