Abstract

Background

This is the second substantive update of this review. It was originally published in 1998 and was previously updated in 2009. Elevated blood pressure (known as 'hypertension') increases with age ‐ most rapidly over age 60. Systolic hypertension is more strongly associated with cardiovascular disease than is diastolic hypertension, and it occurs more commonly in older people. It is important to know the benefits and harms of antihypertensive treatment for hypertension in this age group, as well as separately for people 60 to 79 years old and people 80 years or older.

Objectives

Primary objective

• To quantify the effects of antihypertensive drug treatment as compared with placebo or no treatment on all‐cause mortality in people 60 years and older with mild to moderate systolic or diastolic hypertension

Secondary objectives

• To quantify the effects of antihypertensive drug treatment as compared with placebo or no treatment on cardiovascular‐specific morbidity and mortality in people 60 years and older with mild to moderate systolic or diastolic hypertension

• To quantify the rate of withdrawal due to adverse effects of antihypertensive drug treatment as compared with placebo or no treatment in people 60 years and older with mild to moderate systolic or diastolic hypertension

Search methods

The Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist searched the following databases for randomised controlled trials up to 24 November 2017: the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE Ovid (from 1946), Embase (from 1974), the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and ClinicalTrials.gov. We contacted authors of relevant papers regarding further published and unpublished work.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of at least one year's duration comparing antihypertensive drug therapy versus placebo or no treatment and providing morbidity and mortality data for adult patients (≥ 60 years old) with hypertension defined as blood pressure greater than 140/90 mmHg.

Data collection and analysis

Outcomes assessed were all‐cause mortality; cardiovascular morbidity and mortality; cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality; coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality; and withdrawal due to adverse effects. We modified the definition of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity to exclude transient ischaemic attacks when possible.

Main results

This update includes one additional trial (MRC‐TMH 1985). Sixteen trials (N = 26,795) in healthy ambulatory adults 60 years or older (mean age 73.4 years) from western industrialised countries with moderate to severe systolic and/or diastolic hypertension (average 182/95 mmHg) met the inclusion criteria. Most of these trials evaluated first‐line thiazide diuretic therapy for a mean treatment duration of 3.8 years.

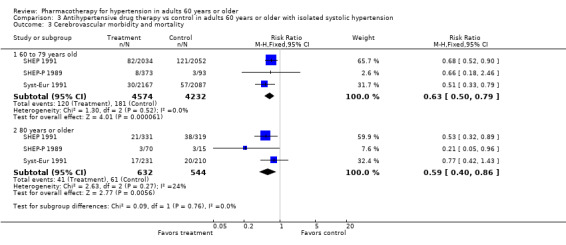

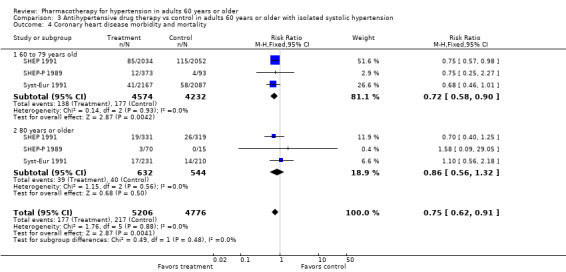

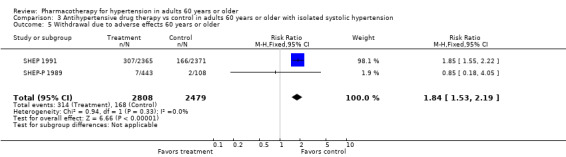

Antihypertensive drug treatment reduced all‐cause mortality (high‐certainty evidence; 11% with control vs 10.0% with treatment; risk ratio (RR) 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 0.97; cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (moderate‐certainty evidence; 13.6% with control vs 9.8% with treatment; RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.77; cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity (moderate‐certainty evidence; 5.2% with control vs 3.4% with treatment; RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.74; and coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity (moderate‐certainty evidence; 4.8% with control vs 3.7% with treatment; RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.88. Withdrawals due to adverse effects were increased with treatment (low‐certainty evidence; 5.4% with control vs 15.7% with treatment; RR 2.91, 95% CI 2.56 to 3.30. In the three trials restricted to persons with isolated systolic hypertension, reported benefits were similar.

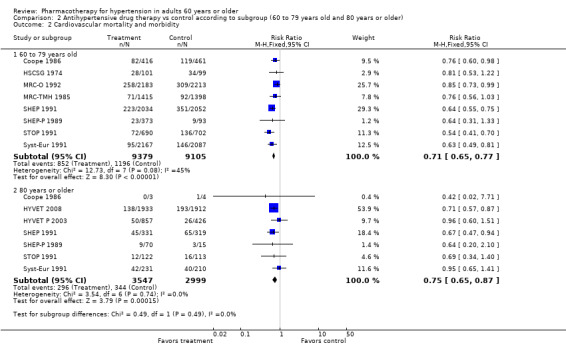

This comprehensive systematic review provides additional evidence that the reduction in mortality observed was due mostly to reduction in the 60‐ to 79‐year‐old patient subgroup (high‐certainty evidence; RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.95). Although cardiovascular mortality and morbidity was significantly reduced in both subgroups 60 to 79 years old (moderate‐certainty evidence; RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.77) and 80 years or older (moderate‐certainty evidence; RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.87), the magnitude of absolute risk reduction was probably higher among 60‐ to 79‐year‐old patients (3.8% vs 2.9%). The reduction in cardiovascular mortality and morbidity was primarily due to a reduction in cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity.

Authors' conclusions

Treating healthy adults 60 years or older with moderate to severe systolic and/or diastolic hypertension with antihypertensive drug therapy reduced all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity, and coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity. Most evidence of benefit pertains to a primary prevention population using a thiazide as first‐line treatment.

Keywords: Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Humans; Middle Aged; Antihypertensive Agents; Antihypertensive Agents/therapeutic use; Hypertension; Hypertension/drug therapy; Coronary Disease; Coronary Disease/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stroke; Stroke/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults 60 years or older

Review question

This is the second update of this review, first published in 1998 and first updated in 2009. We wanted to study the benefits and harms of using blood pressure‐lowering drugs in adults 60 years or older with raised blood pressure.

Search date

We searched the available medical literature to find all trials that compared drug treatment versus placebo or no treatment to examine this question. Data included in this review are up‐to‐date as of November 2017.

Background

High blood pressure, which is common among elderly people 60 years or older, increases the risk of heart attack and stroke.

Study characteristics

We found 16 studies that randomly assigned 26,795 patients 60 years or older with high blood pressure to antihypertensive drug therapy or to placebo or untreated control for a mean duration of 4.5 years.

Key results

Blood pressure‐lowering drug therapy in people with hypertension 60 years and older reduced death, strokes, and heart attacks. Benefit was similar if both upper and lower blood pressure numbers were elevated and if only the upper number was elevated. First‐line treatment used in most studies was a thiazide. More patients withdrew from the studies owing to side effects of these drugs. The magnitude of benefit in cardiovascular mortality and morbidity observed was probably greater among 60‐ to 79‐year‐old patients than in very elderly patients 80 years or older.

Conclusions

Blood pressure‐lowering drug treatment for healthy persons (60 years or older) with raised blood pressure reduces death, heart attacks, and strokes.

Quality of evidence

Review authors graded the quality of evidence as high for reduction in death and as moderate for reduction in stroke and heart attacks.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antihypertensive drug compared to placebo or no treatment in adults 60 years or older.

| Antihypertensive drug therapy compared to placebo or no treatment in adults 60 years or older | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults 60 years or older with primary hypertension Setting: outpatient Intervention: antihypertensive drug therapy Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) |

Relative effect

(95% CI) Fixed‐effect model |

No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control |

Risk with antihypertensive drug therapy |

|||||

| Total mortality Mean duration of 3.8 years |

110 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (93 to 106) |

RR 0.91 (0.85 to 0.97) | 25,932 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ARR = 1% NNTB = 100 |

| Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Mean duration of 3.7 years |

136 per 1000 | 98 per 1000 (92 to 104) |

RR 0.72 (0.68 to 0.77) | 26,747 (15 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ARR = 3.8% NNTB = 27 |

| Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity Mean duration of 3.7 years |

52 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (31 to 39) |

RR 0.66 (0.59 to 0.74) | 26,042 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ARR = 1.8% NNTB = 56 |

| Coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity Mean duration of 2.9 years |

48 per 1000 | 37 per 1000 (33 to 42) |

RR 0.78 (0.69 to 0.88) | 24,559 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ARR = 1.1% NNTB = 91 |

| Withdrawals due to adverse effects Mean duration of 4.6 years |

54 per 1000 | 157 per 1000 (138 to 178) |

RR 2.91 (2.56 to 3.30) | 11,310 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | ARI = 10.3% NNTH = 10 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ARI: absolute risk increase; ARR: absolute risk reduction; CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded due to study limitations (incomplete outcome reporting and selective outcome reporting).

bDowngraded due to high risk of selective reporting bias, as only 4 out of 16 included RCTs reported this outcome.

cDowngraded due to inconsistency (I² > 50%).

Background

Description of the condition

Blood pressure increases with age, and the rate of rise is greater over the age of 60. As a result, the number of people with elevated blood pressure (known as 'hypertension') increases with age. Systolic blood pressure is more strongly associated with cardiovascular disease than is diastolic blood pressure, particularly in older people. Isolated systolic hypertension occurs more commonly in older people. Older people also accumulate higher rates of other risk factors for cardiovascular disease such as obesity, left ventricular hypertrophy, sedentary lifestyle, hyperlipidaemia, and diabetes.

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease in older adults. Hypertension is present in 69% of patients with a first myocardial infarction; in 77% of those with a first stroke; in 74% of those with congestive heart failure; and in 60% of those with peripheral arterial disease (Aronow 2015).

Uncontrolled high blood pressure can lead to heart attack, stroke, aneurysm (life‐threatening if ruptured), heart failure, kidney damage, and vision loss (due to thickened, damaged, or torn blood vessels in the eye).

Description of the intervention

Changing lifestyle ‐ eating a healthy diet with less salt, exercising regularly, quitting smoking, limiting alcohol intake, and maintaining a healthy weight ‐ can help to control high blood pressure. When these lifestyle changes are not enough, treatment with antihypertensive drugs is recommended. Practitioners use several classes of antihypertensive drugs such as diuretics, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin‐receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers to lower blood pressure. They also use other medications to treat high blood pressure, including alpha blockers, alpha‐beta blockers, centrally acting drugs, vasodilators, and aldosterone antagonists.

How the intervention might work

Following are the mechanisms of action of the most commonly used antihypertensive drug classes.

Thiazide and thiazide‐like diuretics lower blood pressure over the long term through a mechanism of action that is not fully understood (Zhu 2005). After long‐term use, thiazides lower peripheral resistance. The mechanism of these effects is uncertain, as it may involve effects on 'whole body', renal autoregulation, or direct vasodilator actions (Hughes 2004). Thiazides act on the kidney to inhibit reabsorption of sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl‐) ions from the distal convoluted tubules in the kidneys by blocking the thiazide‐sensitive Na+‐Cl‐ symporter (Duarte 2010).

Beta blockers are competitive antagonists that block the receptor sites for epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine on adrenergic beta receptors. Some block activation of all types of beta‐adrenergic receptors (β1, β2, and β3), and others are selective for one of the three types of beta receptors (Frishman 2005).

ACE inhibitors block the conversion of angiotensin I (AI) to angiotensin II (AII) and thus decrease the actions of angiotensin II. The end result consists of lowered arteriolar resistance and increased venous capacity; decreased cardiac output, cardiac index, stroke work, and volume; lowered resistance in blood vessels of the kidneys; and increased excretion of sodium in the urine. Renin and AI are increased in concentration in the blood as a result of negative feedback on conversion of AI to AII. Levels of AII and aldosterone are decreased. Bradykinin is increased because ACE is responsible for inactivation of bradykinin.

Angiotensin‐receptor blockers (ARBs) block the activation of angiotensin II AT1 receptors. Blockage of AT1 receptors directly causes vasodilation, reduces secretion of vasopressin, and reduces production and secretion of aldosterone.

Calcium channel blockers block the calcium channel and inhibit calcium ion influx into vascular smooth muscle and myocardial cells. They reduce blood pressure through various mechanisms including vasodilation, reduction in the force of contraction of the heart, slowing of the heartbeat, and direct reduction of aldosterone production.

Alpha1‐adrenergic receptor blockers inhibit the binding of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) to α1 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells. The primary effect of this inhibition is vasodilation, which decreases peripheral vascular resistance, leading to decreased blood pressure.

Central sympatholytic drugs reduce blood pressure mainly by stimulating central α2‐adrenergic receptors in the brainstem centres, thereby reducing sympathetic nerve activity and neuronal release of norepinephrine to the heart and the peripheral circulation.

Vasodilators act directly on the smooth muscle of arteries to relax their walls so blood can move more easily through them.

Why it is important to do this review

Most of the early trials evaluating antihypertensive drug therapy were conducted in lower‐risk people younger than 60 years. The first definitive clinical trial evidence supporting blood pressure‐lowering treatment was produced in the mid‐1980s. Before that time, policy makers and clinicians were reluctant to recommend treatment, particularly for the elderly; some regarded systolic hypertension as a natural feature of aging, and others feared excessive harm from blood pressure lowering in this age group.

When all drug therapies are included in one review, the underlying assumption is that the benefits of lowering blood pressure are independent of the mechanism by which this is achieved. This assumption has not been proven, and it is likely that different drugs lowering blood pressure by different mechanisms will have effects that are independent of the blood pressure‐lowering effect. A drug that lowers blood pressure could have pharmacological and physiological actions independent of blood pressure lowering, and these other actions (both known and unknown) could enhance or negate effects on health outcomes associated with the decrease in blood pressure. This possibility is supported by an analysis suggesting that blood pressure lowering explains only about 50% of the treatment effect in antihypertensive trials (Boissel 2005).

It is important to know and compare the benefits and harms of antihypertensive drug therapy in different age groups of patients with hypertension ‐ 18 to 59 years old; and 60 years or older. Our aim is to document the best available evidence for adult patients 60 years or older. A meta‐analysis in patients 80 years or older from earlier trials by Gueyffier 1999 showed a trend towards increased mortality. Therefore we planned subgroup analyses of patients 60 to 79 years old, and 80 year or older. This is the second substantive update of this review. It was originally published as Mulrow 1998, and the first update was published as Musini 2009.

A Cochrane Review titled "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults age 18 to 59 years old" was published recently (Musini 2017). A Cochrane Review titled "First line drugs for hypertension" has recently been updated (Wright 2018).

Objectives

Primary objective

To quantify the effects of antihypertensive drug treatment as compared with placebo or no treatment on all‐cause mortality in people 60 years and older with hypertension defined as blood pressure greater than 140/90 mmHg.

Secondary objectives

To quantify the effects of antihypertensive drug treatment as compared with placebo or no treatment on cardiovascular‐specific morbidity and mortality in people 60 years and older with hypertension defined as blood pressure greater than 140/90 mmHg.

To quantify the rate of withdrawal due to adverse effects of antihypertensive drug treatment as compared with placebo or no treatment in people 60 years and older with hypertension defined as blood pressure greater than 140/90 mmHg.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only parallel‐group randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of at least one year's duration. Trials must have included a control group that received a placebo or received no antihypertensive treatment. We excluded trials that compared two specific antihypertensive treatments without a placebo or an untreated control.

We excluded trials using other than randomised allocation methods such as alternate allocation, week of presentation, or retrospective controls.

Types of participants

Trials must include only people 60 years of age or older or must separately report outcomes for people 60 or older. Researchers must measure blood pressure using the proper technique at least two times with the participant resting for at least five minutes. Participants must have a systolic blood pressure of at least 140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mmHg at baseline.

Types of interventions

Acceptable antihypertensive drug treatments include angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin‐receptor antagonists, beta‐adrenergic blockers, combined alpha and beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, alpha‐adrenergic blockers, central sympatholytics, direct vasodilators, and peripheral adrenergic antagonists. Investigators could have administered drugs alone or in combination or in fixed or stepped up regimens.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Secondary outcomes

-

Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality* including total stroke, total coronary heart disease, hospitalisation or death from congestive heart failure, and other significant vascular deaths such as ruptured aneurysm

This does not include angina, transient ischaemic attacks, surgical or other procedures, or accelerated hypertension

Cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality including fatal and non‐fatal stroke

Coronary heart disease (CHD) morbidity and mortality including fatal and non‐fatal myocardial infarctions and sudden or rapid cardiac death

Withdrawal due to adverse effects

The original review reported data using different definitions of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity as defined in each individual included study (Mulrow 1994). Refer to Characteristics of included studies.

Please note that for this second substantive update, we have modified the definition of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity to exclude transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) as much as possible (because we judge TIA to be a subjective and less serious outcome). However, when it was not possible to exclude TIA from the total cardiovascular outcome as reported in Mulrow 1998, we report overall effect size in two ways ‐ by including these studies and by deselecting them. We have standardised this update in terms of outcomes and trial identification for consistency with the two complementary reviews (Musini 2017; Wright 2018).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist conducted systematic searches of the following databases for RCTs without language, publication year, or publication status restrictions.

Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web; searched 24 November 2017).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web; searched 24 November 2017).

MEDLINE Ovid (from 1946 onwards), MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print, and MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (searched 24 November 2017).

Embase Ovid (searched 24 November 2017).

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (searched 24 November 2017).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/trialsearch) (searched 24 November 2017).

The Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist modelled subject strategies for databases using the search strategy designed for MEDLINE. When appropriate, we combined these strategies with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying RCTs (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Box 6.4.b) (Higgins 2011a). We translated the MEDLINE search strategy for use with other databases using the appropriate controlled vocabulary, as applicable (Appendix 1). We applied no language restrictions.

The databases searched in the original review and in the first update are presented in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We used previously published meta‐analyses on treatment of hypertension to identify references to trials (Davidson 1987; Staessen 1988; Collins 1990; Staessen 1990a; Staessen 1990b; Leonetti 1992; Thijs 1992; Celis 1993; MacMahon 1993; Insua 1994; Thijs 1994; Pearce 1995; Gueyffier 1996; Psaty 1997; Gueyffier 1999; Quan 1999; Wright JM 1999; BPLTTC 2000; Nikolaus 2000; Psaty 2003; Turnbull 2003; Kang 2004; BBLTTC 2005; Musini 2008; Law 2009; Goeres 2014; Thomopoulos 2014; Sundstrom 2015; Zanchetti 2015; Parsons 2016; Tan 2016; Thomopoulos 2016; Kızılırmak 2017; Wiysonge 2017).

We contacted experts in the field to identify any other trials that we may have missed in our search. We checked the reference lists of included studies and contacted relevant individuals for information about unpublished or ongoing studies. The first version of this review did not provide a study flow diagram. However, the review authors listed 25 studies as excluded with reasons.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We rejected articles on the initial screening if we could determine from the title or the abstract that the article was not a report of a randomised controlled trial, or that there was no possibility that the trial would fit the requirements of this review. Of the articles selected for further review, two review authors (VM and AT) independently assessed whether they would be included or excluded.

Data extraction and management

We abstracted data using a standard data abstraction form; dual abstraction of data from the original reports of trial results by two independent reviewers (VM and AT); and disagreements resolved by discussion. Published results of these meta‐analyses as well as data from additional trials included in the updated review were compared by two review authors (VM and AT). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus (JMW and KB).

The actual endpoints represented by each outcome measure for each study are listed under the "Outcomes" heading of the Characteristics of included studies table. Within each study, the definition of endpoints for each outcome measure is identical between treatment and control groups. The individual non‐fatal outcomes included in the composite endpoint were included as counted by the trialists of each study. Many trials did not report on how events were counted after patients were censored. Refer to personal communication with the author of HYVET 2008 in the risk of bias table to find out how events were counted in that trial.

In this update, we obtained data for Kuramoto 1981,Sprackling 1981,STOP 1991, and VA‐II 1970 from the original Mulrow 1998 and Mulrow 2000 reviews, and the cardiovascular mortality and morbidity outcome definition in these studies did not include transient ischaemic attack. However, data for ATTMH 1981 and Coope 1986 studies included TIA in total cardiovascular outcomes in the original Mulrow 1998 and Mulrow 2000. Therefore in this review, we report overall results for total cardiovascular outcome including these two studies, as well as excluding them from the overall analysis. We excluded TIA data from total cardiovascular mortality and morbidity for several additional studies (SHEP‐P 1989; SHEP 1991; Syst‐Eur 1991 ).

Data for the 60‐ to 64‐year‐old patient subgroup from MRC‐TMH 1985 were obtained by personal communication with Francois Gueyffier from the INDANA Group (Gueyffier 1999). The cardiovascular mortality and morbidity outcome in this study does not include heart failure.

Trial characteristics are detailed in the table Characteristics of included studies. Trials that were excluded are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, and the reasons for exclusion are provided.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (VM and AT) independently assessed risk of bias of each included trial; a third review author (JMW) adjudicated any disagreements. We assessed risk of bias according to Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). We assessed seven domains: randomisation and allocation concealment to assess selection bias; blinding of participants and physician to assess performance bias; blinding of the outcome assessor to assess detection bias; incomplete outcome reporting to assess attrition bias; and selective reporting of outcomes to assess selective reporting bias. We added a category ‐ industry‐sponsored bias ‐ to assess whether the study was funded by the manufacturer and conflict of interest was present, which we assessed as high risk of bias, since researchers may overestimate treatment effect (Lundh 2017).

'Summary of findings' table

We used GRADEpro GDT software to prepare the 'Summary of findings' table (GRADEpro GDT). We decided to include all clinically relevant primary and secondary outcomes such as total mortality, total cardiovascular events, total stroke, total coronary heart disease, and withdrawal due to adverse events.

We considered five factors in grading the overall quality of evidence: limitations in study design and implementation, indirectness of evidence, unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results, imprecision in results, and high probability of publication bias. This approach specifies four levels of quality: high‐, moderate‐, low‐, and very low‐quality evidence. The highest quality rating applies to randomised trial evidence. We downgraded the quality rating by one level for each factor, up to a maximum of three levels for all factors. If we noted severe problems for any one factor (when assessing limitations in study design and implementation, in concealment of allocation, loss of blinding, or attrition over 50% of participants during follow‐up), randomised trial evidence may fall by two levels due to that factor alone.

Measures of treatment effect

We used Review Manager 5.3 for data synthesis and analyses (RevMan 2014). We based quantitative analyses of outcomes on intention‐to‐treat results. We used risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to combine outcomes across trials using the fixed‐effect model. If there was a statistically significant difference in any outcome measure, we presented an absolute risk reduction (ARR), along with the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial (NNTB) or harmful (NNTH) outcome, in the 'Summary of findings' table. This estimate, with 95% confidence intervals (CI), is considered the best point estimate of the average benefit.

Unit of analysis issues

We included only randomised parallel‐group studies in the review. Randomised patients who started treatment in the control group or stopped treatment in the treatment group were still analysed in the treatment group to which they were originally randomised. For all outcome measures reported, we used data from each trial at the end of the follow‐up period mentioned in each trial, which varied from one to six years. Both pilot studies ‐ HYVET P 2003 and SHEP‐P 1989 ‐ had no overlap of participants with the main studies ‐ HYVET 2008 and SHEP 1991, respectively.

Dealing with missing data

When participants were lost to follow‐up, we used data as reported for participants who were followed until end of study in the analyses. Refer to how data were accounted for and included in each study under assessment of attrition bias in the Risk of bias in included studies.

When the primary trials did not report outcomes with exact definitions as listed above, we categorised data to minimise missing data while maintaining the intended study measures. For example, the Medical Research Council Trial of Treatment of Hypertension in Older Adults ‐ MRC‐O 1992 ‐ includes "deaths due to hypertension" in its definition of "cardiovascular events". The broad label "deaths due to hypertension" is not included in the standard definition for "cardiovascular morbidity and mortality" listed above. We included MRCOA's results in the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality outcome measure because "deaths due to hypertension" was congruous with the concept of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The alternative ‐ omitting MRCOA's data ‐ would result in a more reliable measure but at the expense of accuracy of the effect estimate. The number of differences in definitions was small and is unlikely to affect results. Supporting this assumption, previous meta‐analyses found homogeneity of risk reduction among outcome measures suggesting differences in outcome definition were unlikely causes of bias.

Similarly, despite the statement in EWPHBPE 1989 that "The intention‐to‐treat analysis was restricted to the cause and date of death because data on non‐fatal events in patients who dropped out from randomised treatment were not available", we still included data on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular and coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity as was previously done in the "First‐line drugs for hypertension" review (Wright 2018).

One of the trials first included in the 2009 update ‐ HYVET P 2003 ‐ was not conducted according to the standards of Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and did not collect data on serious adverse events, non‐fatal myocardial infarction (MI) or heart failure (personal communication with the author). However, data on cardiovascular mortality and morbidity were reported in the trial and are included in the meta‐analysis. The cardiovascular mortality and morbidity outcome in HYVET P 2003 includes fatal and non‐fatal stroke, fatal MI, other fatal ischaemic heart disease, sudden death, fatal congestive heart failure, fatal atherosclerosis, fatal pulmonary embolism, fatal hypertension, and fatal aortic aneurysm but does not include TIA.

Two trials ‐ ATTMH 1981 and Coope 1986 ‐ included TIA in total cardiovascular outcome, and we have reported overall effect size by including these two studies as well as by excluding them from the analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested heterogeneity of treatment effect between trials using a standard Chi² statistic, and we used the I² statistic to estimate the amount of heterogeneity. We used the fixed‐effect model to obtain summary statistics of pooled trials in patients 60 years or older. In case heterogeneity was found to be significant, we planned to perform sensitivity analyses using the random‐effects model. Subgroup analyses were compared using the fixed‐effect model.

Assessment of reporting biases

Several RCTs in adults 18 years or older with hypertension met the minimum inclusion criteria. However they did not report data separately in patients 60 years or older. Table 2 lists these 15 studies.

1. RCTs meeting the minimum inclusion criteria but not providing data in patients ≥ 60 with hypertension.

| ACTIVE I 2011 | Randomised trial comparing irbesartan 300 mg/d or double‐blind placebo in patients 55 years or older for a mean follow‐up of 4.1 years. 52% of patients had hypertension at baseline. Data are not available for hypertensive patients 60 years or older |

| Barraclough 1973 | Single‐blind randomised placebo‐controlled trial in patients 45 to 69 years old for a mean follow‐up of 1.5 years. Data for 60‐ to 69‐year‐old patients are not available |

| Bull 2015 | Randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial in adult patients 18 years or older with moderate or severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis. 32% of patients had hypertension at baseline. Participants were randomised to ramipril 10 mg daily or placebo for 1 year. Data are not reported separately in hypertensive subgroup of patients 60 years or older |

| DREAM 2006 | Double‐blind RCT in participants 30 years or older without cardiovascular disease but with impaired fasting glucose levels (after an 8‐hour fast) or impaired glucose tolerance. Participants were randomised to ramipril (up to 15 mg per day) or placebo (and rosiglitazone or placebo) and were followed for a median of 3 years. 43.7% of patients at baseline had a history of hypertension. Data are not reported for patients with hypertension who were 60 years or older |

| DUTCH ‐TIA 1993 | Randomised double‐blind trial comparing atenolol 50 mg daily to placebo in patients 65 years or older who had a TIA for a mean follow‐up period of 2.6 years. Data for those 60 and over with hypertension at baseline were not available |

| HOPE‐HYP 2000 | Double‐blind RCT in patients 55 years or older with previous coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease or diabetes plus one additional risk factor. Participants randomised to ramipril 2.5 mg titrated up to 0 mg/d or placebo. Average follow‐up was 4.5 years. Data are not reported separately for people 60 years or older with hypertension |

| IPPPSH 1985 | Randomised trial in 40‐ to 64‐year‐old patients with hypertension randomised to oxprenolol or placebo for a mean follow‐up of 3.5 years. Data are not reported separately for participants 60 to 64 years of age |

| Materson 1993 | Randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled study of male veterans 21 years or older with DBP of 95 to 109 mmHg. Participants randomised to placebo or to 1 of the 6 drugs ‐ HCTZ 12.5 to 50 mg/d; atenolol 25 to 100 mg/d; captopril 25 to 100 mg/d; clonidine 0.2 to 0.6 mg/d; sustained preparation of diltiazem 120 to 360 mg/d; or prazosin 4 to 20 mg/d ‐ for a period of 1 year. Morbidity and mortality outcomes not reported for different drug classes nor for patients 60 years or older |

| PATS 1995 | Randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial conducted in Chinese patients with mean age 60 ± 8 years. Participants were randomised to indapamide 2.5 mg/d or placebo. Data are not reported separately for patients 60 years or older |

| TEST 1995 | Randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial conducted in 720 Swedish patients > 40 years old, within 3 weeks of a stroke or transient ischaemic attack with a mean follow‐up period of 30 months. Data are not reported separately for patients 60 years or older |

| TOMHS 1995 | Four‐year double‐blind placebo‐controlled randomised trial in patients with mild hypertension (average blood pressure, 140/91 mmHg) aged 45 to 69 years. Participants randomised to receive nutritional‐hygienic intervention plus 1 of 6 treatments: (1) placebo; (2) diuretic (chlorthalidone); (3) beta blocker (acebutolol); (4) alpha 1 antagonist (doxazosin mesylate); (5) calcium antagonist (amlodipine maleate); or (6) angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (enalapril maleate). Morbidity and mortality events were not reported separately for the different drug treatments. Corresponding author was contacted, but data for 60‐ to 69‐year‐old patients were not provided |

| UKPDS 39 1998 | Randomised controlled open‐label trial conducted in newly diagnosed patients 25 to 65 years old with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Participants were randomised to captopril or atenolol or placebo and were followed for 8.4 years. Data for patients 60 to 65 years old are not reported separately |

| VA Coop 1962 | Randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled study of 1 year's duration in 759 hypertensive patients. The study recruited men less than 70 years old. This study did not report results separately for those 60 to 69 years old |

| VA‐I 1967 | Randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial conducted in ambulatory patients in the USA with mean age 51 years. Age range not reported. Participants were randomised to hydrochlorothiazide 100 mg plus reserpine 0.2 mg plus hydralazine 75 mg or 150 mg or placebo. Mean follow‐up was 1.5 years. Data for patients 60 years or older are not reported separately |

| Wolf 1966 | Double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial conducted in ambulatory patients in the USA with mean age 50 years. Participants were randomised to reserpine 0.25 mg t.i.d., chlorothiazide 0.5 g b.i.d., or hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg q.i.d. plus guanethidine if needed or placebo. Mean follow‐up was 2 years. Data for patients 60 years or older are not reported separately |

DBP: diastolic blood pressure.

HCTZ: hydrochlorothiazide.

RCT: randomised controlled trial.

TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

We had planned to use a funnel plot to assess the possibility of publication bias for outcomes that were reported in 10 or more studies. A test for funnel plot asymmetry (small‐study effects) formally examines whether the association between estimated intervention effects and a measure of study size is greater than might be expected to occur by chance, one cause of which is publication bias.

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager 5.3 to perform data synthesis and analyses (RevMan 2014). We presented dichotomous outcomes as RRs with 95% CIs using a fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

A meta‐analysis in patients 80 years or older from earlier trials ‐ Gueyffier 1999 and Bejan‐Angoulvant 2010 ‐ showed a trend towards increased mortality. Therefore, we planned analyses in subgroups of patients 60 to 79 years old and 80 years or older and assessed differences among subgroups using an interaction test. Furthermore, two randomised trials ‐ HYVET P 2003 and HYVET 2008 ‐ were specifically done in the 80 years or older group of patients and were included in the first update. A Cochrane Review on the specific age group of young adults (18 to 59 years) has been recently published (Musini 2017), and the Cochrane Review on "First line drugs for hypertension" in adult patients 18 years or over has been recently updated (Wright 2018).

When heterogeneity was estimated to be significant (I² > 50%), we attempted to identify trials that would contribute to heterogeneity and to explore their population characteristics, baseline blood pressure (BP), blinded or open‐label study design, use of antihypertensive drugs as fixed dose or stepped up therapy, or response to placebo that would possibly explain the reason for heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

To test for robustness of results, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. We analysed data using random‐effects models. Other sensitivity analyses included restricting meta‐analysis to trials that were blinded (participant and/or provider) and to trials that contained a placebo control only. We also analysed results when removing trials that had enrolled populations restricted to persons who had previously suffered a stroke. We analysed results of trials restricted to persons with isolated systolic hypertension both as a separate group and combined with trials also assessing persons with both systolic and diastolic hypertension.

Results

Description of studies

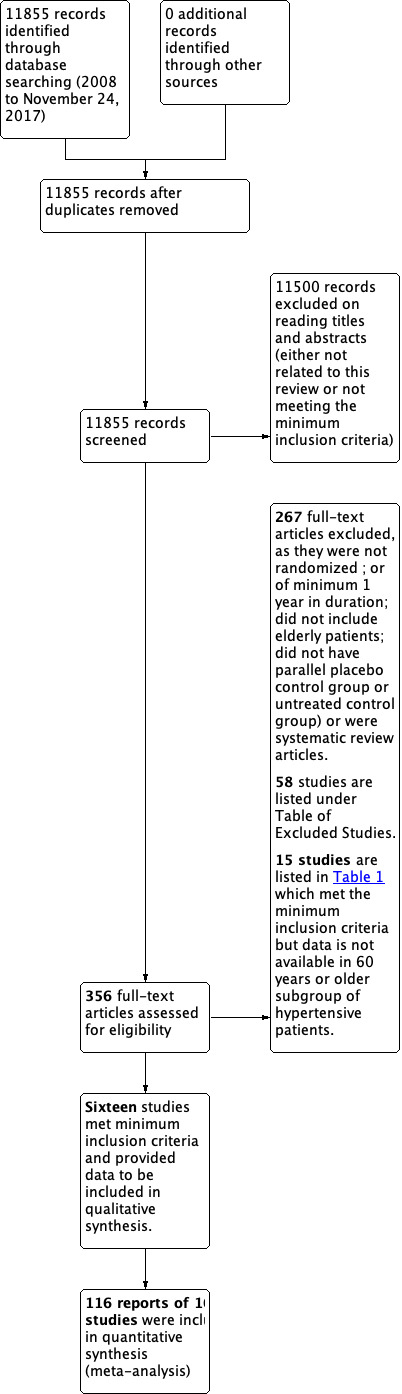

See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

The updated search strategy until November 2017 resulted in 11,855 new citations. Titles and abstracts were screened, and 11,500 were excluded. The remaining 356 full‐text articles were retrieved. None of them met the minimum inclusion criteria mostly because they did not have a placebo or no treatment comparison group; were not one year in duration; or did not have a true no treatment control group.

The Mulrow 1998 original review included 15 studies. In the first update, 13 of the original studies were included and 2 studies ‐ CASTEL 1994 and HDFP 1984 ‐ were excluded, as explained in Characteristics of excluded studies. In addition to the 13 studies in the original review, the first update included 2 new studies ‐ HYVET 2008 and HYVET P 2003 ‐ which exclusively studied patients 80 years or older with hypertension.

For this update, we were able to add the MRC‐TMH 1985 study because data on clinical outcomes for participants 60 to 64 years old were kindly provided by Francois Gueyffier from the INDANA Group (Gueyffier 1999).

A total of 116 reports of 16 studies met the inclusion criteria and are included in this second update. Table 2 lists 15 additional studies that meet the minimum inclusion criteria but do not provide aggregate data for the 60 years or older subgroup of participants. A future update may consider adapting the protocol and requesting this data for individual patient data (IPD) analysis.

Included studies

Sixteen trials (N = 26,795) in healthy ambulatory adults 60 years or older with moderate to severe systolic and/or diastolic hypertension (average 182/95 mmHg) met the inclusion criteria. Most of these trials evaluated first‐line thiazide diuretic therapy for a mean treatment duration of 3.8 years (Table 3).

2. Details of studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

| Number |

Study (N = randomised 60 years or older) Blinding |

Baseline SBP/DBP |

Mean age (range), years |

Control group | Antihypertensive drug treatment used | Outcomes reported |

| 1 |

ATTMH 1981 (N = 582) Double‐blind (identified as ANBP 1981 in original Mulrow review) |

165/101 | 64 (60 to 69) |

Placebo | First‐line ‐ chlorothiazide 500 mg, second‐line ‐ dose increased to 1000 mg, or addition of methyldopa, propranolol, or pindolol. Third‐line drugs added were hydralazine or clonidine | Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity |

| 2 |

Carter 1970 (N = 48) Open‐label |

Not reported | 69 (60 to 79) |

Observation (untreated control group) |

Bendrofluazide (93%), methyldopa, and debrisoquine | Mortality |

| 3 |

Coope 1986a (N = 884) Open‐label (identified as HEP 1986 in original Mulrow review) |

196/99 | 69 (60 to 79) |

Observation | First‐line ‐ atenolol 100 mg daily; second‐line ‐ bendrofluazide 5 mg daily; third‐line ‐ methyldopa 500 mg daily; fourth‐line ‐ any recognised therapy In the last 2 years of the trial, several participants were treated with nifedipine retard 20 mg morning and night |

Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 4 |

EWPHBPE 1989 (N = 840) Double‐blind |

183/101 | 72 (60 to 97) |

Placebo | First‐line ‐ hydrochlorothiazide 25 to 50 mg + triamterene 50 to 100 mg daily; second‐line ‐ methyldopa 250 to 2000 mg daily | Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 5 |

HSCSG 1974 (N = 200) Double‐blind (identified as HTN‐COOP 1976 in original Mulrow review) |

167/100 | Not reported (60 to 75) |

Placebo | Deserpidine 1 mg plus methyclothiazide 10 mg | Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 6 |

HYVET 2008 (N = 3845) Double‐blind 80 years or older |

173/91 | 84 (80 to 105) |

Placebo | First‐line‐ indapamide 1.5 mg daily; second‐line ‐ perindopril 2 mg daily; third‐line ‐ perindopril 4 mg daily | Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 7 |

HYVET P 2003 (N = 1283) Open‐label 80 years or older |

182/100 | 84 (80 to 96) |

Observation | First‐line ‐ diuretic (usually bendrofluazide 2.5 mg), an ACE inhibitor (usually lisinopril 2.5 mg), or no treatment; second‐line ‐ involved doubling the dose of the first drug; third‐line ‐ involved adding diltiazem slow‐release 120 mg daily; fourth‐line ‐ involved adding diltiazem slow‐release 240 mg daily | Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 8 |

Kuramoto 1981 (N = 91) Double‐blind |

169/86 | 76 (> 60) |

Placebo | First‐line ‐ trichlormethiazide 1 to 4 mg; 80% monotherapy; second‐line ‐ reserpine (0.3 mg), methyldopa (125 to 500 mg), and hydralazine (50 to 100 mg) added |

Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 9 |

MRC‐O 1992 (N = 4396) Single‐blind |

184/91 | 70 (60 to 74) |

Placebo | Diuretic arm: First‐line ‐ hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg or 50 mg + amiloride 2.5 mg or 5 mg daily; second‐line ‐ atenolol 50 mg daily; third‐line ‐ nifedipine up to 20 mg daily; fourth‐line ‐ other drugs Beta blocker arm: First‐line ‐ atenolol 50 mg daily; second‐line ‐ hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg or 50 mg + amiloride 2.5 mg or 5 mg daily; third‐line ‐ nifedipine up to 20 mg daily; fourth‐line ‐ other drugs |

Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 10 |

MRC‐TMH 1985 60‐ to 64‐year‐old subgroup (N = 2813) Single‐blind |

Not reported in this subgroup | Not reported (60 to 74) |

Placebo | Bendrofluazide 10 mg daily, propranolol 80 to 240 mg daily; methyldopa added if required | Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 11 |

SHEP 1991 (N = 4736) Double‐blind |

170/77 | 72 (60 or older) |

Placebo | First‐line ‐ chlorthalidone 12.5 or 25 mg daily; second‐line ‐ atenolol 25 or 50 mg or reserpine 0.05 or 0.10 mg daily | Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 12 |

SHEP‐P 1989 (N = 551) Double‐blind |

172/75 | 72 (60 or older) |

Placebo | Fisrt‐line ‐ chlorthalidone 25 to 50 mg daily (87%); second‐line ‐ hydralazine 25 mg twice daily, reserpine 0.05 mg twice daily, or metoprolol 50 mg twice daily (13%) | Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 13 |

Sprackling 1981a (N = 123) Open‐label |

199/106 | 81 (60 or older) |

Observation | Methyldopa 250 mg twice daily | Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity |

| 14 |

STOP 1991a (N = 1627) Double‐blind |

195/102 | 76 (70 to 84) |

Placebo | First‐line ‐ atenolol 50 mg daily or hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg + amiloride 2.5 mg daily, or metoprolol 100 mg daily, or pindolol 5 mg daily; second‐line ‐ patients on a beta blocker received diuretics, and those on diuretics received a beta blocker | Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 15 |

Syst‐Eur 1991 (N = 4695) Double‐blind |

174/86 | 70 (60 or older) |

Placebo | First‐line ‐ nitrendipine 10 mg daily, 10 mg BID, 20 mg BID; second‐line ‐ enalapril 5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg daily in evening and/or hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 to 25 mg/d in morning |

Mortality Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| 16 |

VA‐II 1970 (N = 81) Double‐blind |

176/103 | Not reported (60 to 75) |

Placebo | First‐line ‐ HCTZ 100 mg plus reserpine 0.2 mg; second‐line ‐ hydralazine 75 to 150 mg | Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity CHD mortality and morbidity |

| A total of 16 trials | N = 26,795 | SBP ranged from 165 to199 mmHg and DBP from 75 to 106 mmHg |

Mean age 64 to 84 years; age ranged from 60 to 105 years |

12 placebo‐controlled studies; 4 studies with observation as control group |

Drugs used included thiazides, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, methyldopa, reserpine, hydralazine, and clonidine |

aStudies with baseline SBP > 190 mmHg.

ACE: angiotensin‐converting enzyme.

CHD: coronary heart disease.

DBP: diastolic blood pressure.

SBP: systolic blood pressure.

For most participants included in this review, mean age ranged from 64 to 84 years. Two trials did not report mean age (MRC‐TMH 1985; VA‐II 1970). Four trials originally included both younger and older persons (ATTMH 1981; Carter 1970; HSCSG 1974; MRC‐TMH 1985). Only data on those older than 60 are reported from these trials. The average age across trials was 73.8 years. Seven trials evaluated participants over 60 years of age (EWPHBPE 1989; Kuramoto 1981; MRC‐O 1992; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐P 1989; Sprackling 1981; Syst‐Eur 1991). The Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension specifically evaluated people over age 70 (STOP 1991). The HYVET P 2003 and HYVET 2008 trials studied patients 80 years or older. In all, 14,663 participants (54.7%) were female.

Most trials were conducted in Western industrialised countries ‐ USA (20%), UK (32%), European multi‐site trials (40%), Sweden (5%), Australia (2%), and Japan (< 1%) ‐ and evaluated first‐line diuretics (ATTMH 1981;Carter 1970; EWPHBPE 1989; HYVET 2008; HYVET P 2003; Kuramoto 1981;MRC‐O 1992;MRC‐TMH 1985; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐P 1989; VA‐II 1970). HYVET P 2003 recruited patients from Bulgaria (88%), Spain (3%), Romania (3%), UK (2.5%), and Poland (1.5%), and from other countries in smaller numbers (Finland, Lithuania, Ireland, Greece, and Serbia). HYVET 2008 recruited patients from Western Europe (2.2%), Eastern Europe (55.8%), China (39.6%), Australasia (0.5%), and Tunisia (1.9%).

Five trials evaluated beta blocker therapies (Coope 1986; MRC‐O 1992; MRC‐TMH 1985; STOP 1991). HYVET P 2003 evaluated thiazides as well as ACE inhibitors versus placebo. No randomised controlled trial comparing alpha‐adrenergic blockers or angiotensin‐receptor blockers to placebo or untreated controls was identified.

The four trials based in the USA reported ethnicity as African American: SHEP 1991 (14%); SHEP‐P 1989 (18% non‐white); VA‐II 1970 (41%); and HSCSG 1974 (78%). All participants in ATTMH 1981 and STOP 1991 were white. Ten trials did not report ethnicity (Carter 1970; Coope 1986; EWPHBPE 1989; HYVET P 2003; HYVET 2008; Kuramoto 1981; MRC‐O 1992; MRC‐TMH 1985; Sprackling 1981Syst‐Eur 1991).

Study populations predominantly consisted of ambulatory patients recruited from the community or from primary care facilities. A small proportion (6%) of patients were recruited from hospitals or homes for the aged. Studies did not consistently report data on pre‐existing conditions among participants; available data follow. Two studies were limited to stroke survivors (Carter 1970; HSCSG 1974). Six other trials reported the baseline prevalence of stroke. The sample size‐based weighted average prevalence across these six trials was 3.6%:SHEP‐P 1989 (1%), SHEP 1991 (1.4%), Syst‐Eur 1991 (3.5%), Sprackling 1981 (11.3%), HYVET P 2003 (4.5%), and HYVET 2008 (6.8%). Six trials reported the baseline prevalence of myocardial infarction. Average prevalence across trials was 2.3%: ATTMH 1981 (0.5%), Syst‐Eur 1991 (1.2%), SHEP‐P 1989 (4%), SHEP 1991 (4.9%), HYVET P 2003 (3.0%), and HYVET 2008 (3.1%). Two studies excluded patients with diabetes (ATTMH 1981;MRC‐O 1992), while three other trials reported the baseline prevalence. Average prevalence across trials was 9.2%: HYVET 2008 (6.8%), SHEP 1991 (10.1%), and HSCSG 1974 (36%). Two trials reported the baseline prevalence of hyperlipidaemia: HSCSG 1974 (22%) and ATTMH 1981 (62.2%). Ten trials reported the baseline prevalence of smoking. Average prevalence across trials was 12.1%: HYVET P 2003 (4.2%), HYVET 2008 (6.6%), Syst‐Eur 1991 (7.3%), SHEP‐P 1989 (11%), SHEP 1991 (12.7%), EWPHBPE 1989 (16.4%), ATTMH 1981 (17.5%), MRC‐O 1992 (17.5%), Coope 1986 (24%), and HSCSG 1974 (60%). Only HSCSG 1974 reported data on prevalence of obesity (29%).

Entry diastolic blood pressure criteria also have varied somewhat from trial to trial. However, trials in older persons have not routinely included patients with higher diastolic blood pressure than trials in younger persons. All trials except Carter 1970 and a subgroup in MRC‐TMH 1985 reported mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) at baseline. SHEP‐P 1989, SHEP 1991, and Syst‐Eur 1991 restricted recruitment to persons with isolated systolic hypertension, defined as SBP 160 to 219 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg (SHEP 1991; SHEP‐P 1989), or as DBP < 95 mmHg (Syst‐Eur 1991).

Mean blood pressure at entry in the three isolated systolic hypertension trials was 172/81 mmHg. Two studies recruited persons with isolated systolic hypertension, diastolic hypertension, or systo‐diastolic hypertension (Carter 1970; Coope 1986). Kuramoto 1981 and MRC‐O 1992 recruited patients with isolated systolic hypertension or systo‐diastolic hypertension. HYVET P 2003 recruited patients with systolic and/or diastolic hypertension (SBP > 140 mmHg and DBP 90 to 109 mmHg). HYVET 2008 recruited patients with persistent hypertension defined as SBP of 160 to 199 mmHg and DBP < 110 mmHg. In all, 32.5% of patients in HYVET 2008 had isolated systolic hypertension. The remainder of the studies required that patients' DBP be at least 90 mmHg. Mean BP at entry was 182/95 mmHg.

See the "Participants" heading in the Characteristics of included studies table for a complete description of each study's blood pressure inclusion criteria. The mean sitting SBP/DBP in HYVET P 2003 was 182/99.6 mmHg, and in HYVET 2008 173/90.8 mmHg.

Thirteen of the 16 trials instituted a stepped care approach to hypertension treatment. In more than 70% of trials, a thiazide diuretic was the first‐line drug used for the treatment group. Seven trials started the treatment group exclusively on a thiazide diuretic (ATTMH 1981;Carter 1970; EWPHBPE 1989; HYVET 2008; Kuramoto 1981;SHEP‐P 1989; SHEP 1991). Coope 1986,MRC‐TMH 1985, and STOP 1991 started the treatment group on a diuretic or a beta blocker. MRC‐O 1992 randomised the treatment group to two arms ‐ one initially receiving diuretics, and the other initially receiving a beta blocker. Syst‐Eur 1991 started the treatment group on a calcium channel blocker. HYVET P 2003 started one treatment arm on a diuretic, and the other treatment arm on an ACE inhibitor. Second‐ and third‐line drugs included diuretics, beta blockers, centrally acting antiadrenergic agents, peripherally acting antiadrenergic agents, vasodilators, converting‐enzyme inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers. See the "Interventions" heading in the Characteristics of included studies table for a complete description of each study's drug treatment protocol.

Four trials maintained participants on a particular therapeutic regimen (i.e. not stepped care) throughout the study. VA‐II 1970 treated participants with a combination diuretic ‐ centrally acting antiadrenergic agent (hydrochlorothiazide/reserpine) ‐ plus a vasodilator (hydralazine). HSCSG 1974 treated participants with a diuretic (methyclothiazide) and a peripherally acting antiadrenergic agent (deserpidine). Sprackling 1981 treated participants with a centrally acting antiadrenergic agent (methyldopa). MRC‐TMH 1985 treated participants with a fixed dose of bendrofluazide10 mg or propranolol 80 to 240 mg and added methyldopa if required.

HYVET P 2003 randomised participants to three groups: no treatment, diuretic‐based treatment (usually bendroflumethiazide 2.5 mg), and an ACE inhibitor (ACEI)‐based regimen (usually lisinopril 2.5 mg). To attain target blood pressure (sitting SBP < 150 mmHg and sitting DBP < 80 mmHg) in the actively treated groups, the dose of diuretic or ACEI could be doubled (step 2); diltiazem slow release 120 mg could be added (step 3); or diltiazem slow release 240 mg could be added (step 4).

HYVET 2008 randomised participants to either indapamide sustained release 1.5 mg or matching placebo. To reach target blood pressure (SBP < 150 mmHg and DBP < 80 mmHg), perindopril 2 mg or 4 mg or matching placebo could be added.

Length of study follow‐up ranged from relatively short ‐ 1 year in HYVET P 2003 or 2 years in STOP 1991,Syst‐Eur 1991, and HYVET 2008 ‐ to relatively long ‐ the rest of the trials lasted three to six years. All trials were multi‐site studies except for Carter 1970 and Kuramoto 1981. The mean duration of treatment was 4.5 years in adults 60 years or older; 4 years among 60‐ to 79‐year‐olds; and 2.8 years in patients 80 years of age or older. The mean duration of treatment was 3.2 years in trials with isolated systolic hypertension in patients 60 years or older.

Twelve trials were placebo controlled (ATTMH 1981; EWPHBPE 1989; HSCSG 1974; HYVET 2008; Kuramoto 1981;MRC‐O 1992; MRC‐TMH 1985; SHEP‐P 1989; SHEP 1991; STOP 1991; Syst‐Eur 1991; VA‐II 1970). In four trials, the control group received no treatment (Carter 1970; Coope 1986; HYVET P 2003; Sprackling 1981).

Studies included in this review allowed participants in the control group to receive antihypertensive therapy because their blood pressure exceeded pre‐set "escape" criteria. Also, a portion of participants assigned to the treatment group stopped taking their assigned medication because they had adverse drug effects, or because they achieved normal blood pressure. Percentages of participants assigned to the control group who were receiving antihypertensive medication by the end of the trial were as follows: Coope 1986 9%; Kuramoto 1981 17%; STOP 1991 23%; Syst‐Eur 1991 27%; ATTMH 1981 35%; SHEP‐P 1989 40%; SHEP 1991 44%; MRC‐O 1992 53%; EWPHBPE 1989 > 35%; HYVET P 2003 0.8%; and HYVET 2008 0.6%. The remaining five trials did not report such data. Percentages of participants assigned to the treatment group who had ceased taking antihypertensive medication by the end of the trial were as follows: ATTMH 1981 33%; Coope 1986 5%; EWPHBPE 1989 > 35%; HYVET P 2003 4%; HYVET 2008 0.5%; MRC‐O 1992 ‐ diuretic arm 48%; MRC‐O 1992 beta blocker arm 63%; SHEP 1991 10%; SHEP‐P 1989 30%; STOP 1991 16%; and Syst‐Eur 1991 18%. The remaining five trials did not report such data. However, those in the control group who started treatment and those in the treatment group who stopped treatment were still analysed in the treatment group to which they were randomised (intention‐to‐treat analyses).

Excluded studies

Two RCTs ‐ HDFP 1984 and CASTEL 1994 ‐ were included in the original 1998 version of this review but were excluded from the first update, as the control group in these studies was not an untreated or placebo control group. HDFP 1984 was excluded because it provided a multi‐factorial intervention, and CASTEL 1994 was excluded because the control group was receiving non‐specific antihypertensive therapy from their personal physician.

A total of 58 studies were excluded from this update and are listed with reasons for exclusion under Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

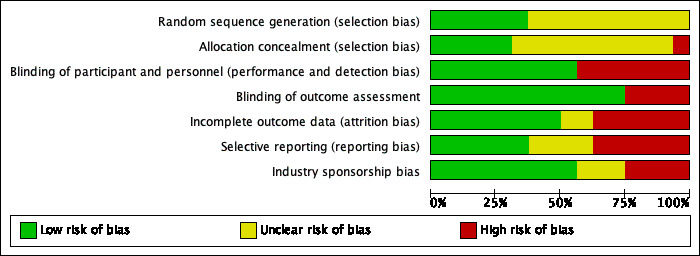

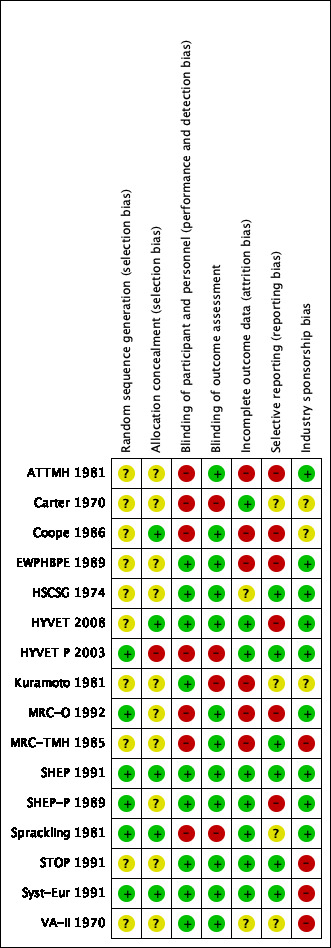

Refer to Figure 2 and Figure 3 for visual summaries of the risk of bias assessment.

2.

Methodological quality graph: Each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary of each included trial.

Allocation

In older trials, lack of reporting of the method used for randomisation or allocation concealment is common, and we assessed risk of bias in these trials as unclear.

Randomisation was assessed as having low risk of bias in six trials (HYVET P 2003; MRC‐O 1992; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐P 1989; Sprackling 1981; Syst‐Eur 1991), and as having unclear risk of bias in 10 trials (ATTMH 1981; Carter 1970; Coope 1986; EWPHBPE 1989; HSCSG 1974; HYVET 2008; Kuramoto 1981; MRC‐TMH 1985; STOP 1991; VA‐II 1970).

Allocation concealment was assessed as having low risk of bias in five trials (Coope 1986; HYVET 2008; SHEP 1991; Sprackling 1981; Syst‐Eur 1991), as having unclear risk of bias in 10 trials (ATTMH 1981; Carter 1970; EWPHBPE 1989; HSCSG 1974; Kuramoto 1981; MRC‐O 1992; MRC‐TMH 1985; SHEP‐P 1989; STOP 1991; VA‐II 1970), and as having high risk of bias in one trial (HYVET P 2003).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel was assessed as having low risk of bias in nine trials (EWPHBPE 1989; HSCSG 1974; HYVET 2008; Kuramoto 1981; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐P 1989; STOP 1991; Syst‐Eur 1991; VA‐II 1970), and as having high risk of bias in seven trials (ATTMH 1981; Carter 1970; Coope 1986; HYVET P 2003; MRC‐O 1992; MRC‐TMH 1985; Sprackling 1981).

Blinding of outcome assessors was assessed as having low risk of bias in twelve trials (ATTMH 1981; Coope 1986; EWPHBPE 1989; HSCSG 1974; HYVET 2008; MRC‐O 1992; MRC‐TMH 1985; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐P 1989; STOP 1991; Syst‐Eur 1991), and as having high risk of bias in four trials (Carter 1970; HYVET P 2003; Kuramoto 1981; Sprackling 1981).

Incomplete outcome data

Providing incomplete outcome data was assessed as having low risk of bias in eight trials (Carter 1970; HYVET 2008; HYVET P 2003; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐P 1989; Sprackling 1981; STOP 1991; Syst‐Eur 1991), as having unclear risk of bias in two trials (HSCSG 1974; VA‐II 1970), and as having high risk of bias in six trials (ATTMH 1981; Coope 1986; EWPHBPE 1989; Kuramoto 1981; MRC‐O 1992; MRC‐TMH 1985).

Selective reporting

Selective reporting was assessed as having low risk of bias in seven trials (Carter 1970; HSCSG 1974; HYVET P 2003; MRC‐TMH 1985; SHEP 1991; STOP 1991; Syst‐Eur 1991), unclear risk in three trials (Kuramoto 1981; Sprackling 1981; VA‐II 1970), and high risk in six trials (ATTMH 1981; Coope 1986; EWPHBPE 1989; HYVET 2008; MRC‐O 1992; SHEP‐P 1989).

Other potential sources of bias

Industry sponsorship was assessed as having low risk of bias in nine trials (ATTMH 1981; EWPHBPE 1989; HSCSG 1974; HYVET 2008; HYVET P 2003; MRC‐O 1992; SHEP 1991; SHEP‐P 1989; Sprackling 1981), unclear risk of bias in three trials (Carter 1970; Coope 1986; Kuramoto 1981), and high risk of bias in four trials (MRC‐TMH 1985; STOP 1991; Syst‐Eur 1991; VA‐II 1970).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Analyses were performed on the combined results of all 16 studies. The three trials that included only people with isolated systolic hypertension were included in the overall analyses and were also analysed separately (SHEP‐P 1989; SHEP 1991; Syst‐Eur 1991).

EWPHBPE 1989 reported intention‐to‐treat data for mortality only; the morbidity data reported from EWPHBPE 1989 did not undergo intention‐to‐treat analysis. The occurrence of any trial endpoint in ATTMH 1981 terminated participation in the study. Thus, true intention‐to‐treat data for ATTMH 1981 are available only for combined cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. We decided to include data for all outcomes from both EWPHBPE 1989 and ATTMH 1981, similar to what was done in the Cochrane Review titled "First line drugs for hypertension" (Wright 2018).

Individual differences in patient characteristics or disease severity are associated with different levels of risk to experience an adverse event. In the aggregate, these individual differences contribute to the proportion of patients we expect to experience an event within a population. Variation in level of risk in different patient populations, both within and between clinical trials, is often associated with variability in treatment outcomes (Ioannidis 1997; Schmid 1998). This average population risk is unknown but contributes to the proportion of events experienced by a placebo control group in a randomised trial. We use the term 'control rate' to describe the probability that a member of the control group experiences the adverse event, and we use this sample value to estimate the aggregate population risk for patients enrolled in a clinical trial.

In adults 60 years or older

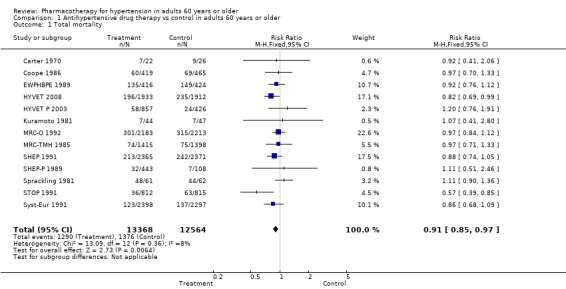

All‐cause mortality

In the 13 trials reporting mortality data for people 60 years or older, treatment caused a significant reduction in all‐cause mortality (risk ratio (RR) 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 0.97; participants = 25,932; studies = 13; I² = 8%). See Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control in adults 60 years or older, Outcome 1 Total mortality.

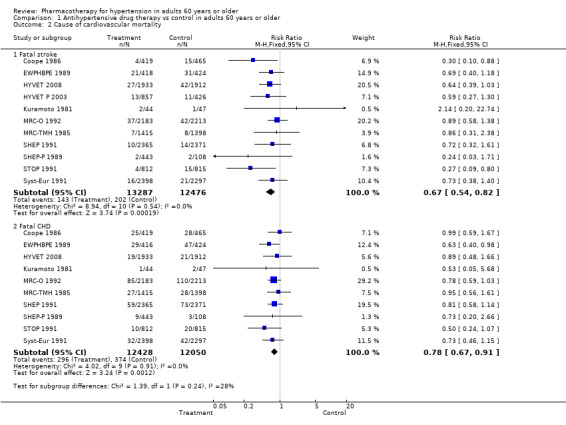

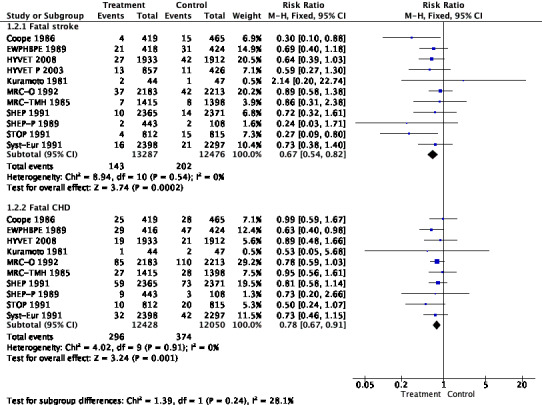

Mortality was significantly reduced due to reductions in fatal stroke and fatal CHD. See Analysis 1.2 and Figure 4.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control in adults 60 years or older, Outcome 2 Cause of cardiovascular mortality.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control in adults 60 years or older, outcome: 1.2 Cause of cardiovascular mortality.

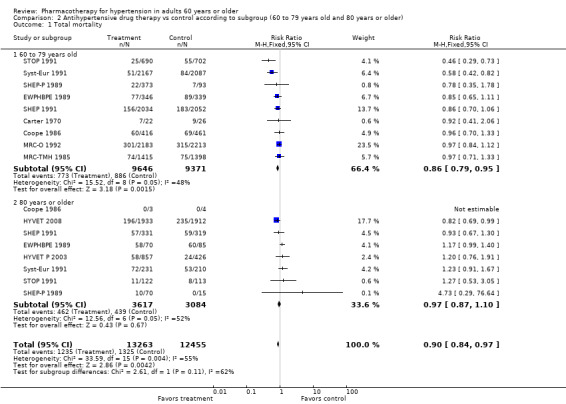

For subgroups, refer to Analysis 2.1. Investigating treatment effects between the two subgroups showed no significant differences. Tests for subgroup differences showed the following: Chi² = 2.61, df = 1 (P = 0.11), I² = 61.7%.

2.1. Analysis.

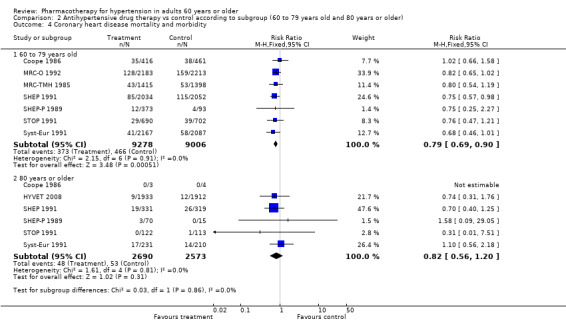

Comparison 2 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control according to subgroup (60 to 79 years old and 80 years or older), Outcome 1 Total mortality.

People 60 to 79 years old (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.95; participants = 19,017; studies = 9; I² = 48%); all‐cause mortality was significantly reduced in the 60‐ to 79‐year‐old subgroup.

People 80 years or older (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.10; participants = 6701; studies = 8; I² = 52%).

Baseline risk of mortality in the control group among patients 60 to 79 years old ranged from 4% in Syst‐Eur 1991 to 34.6% in Carter 1970, and in the 80 years or older group from 0% in SHEP‐P 1989 to 71% in SHEP 1991.

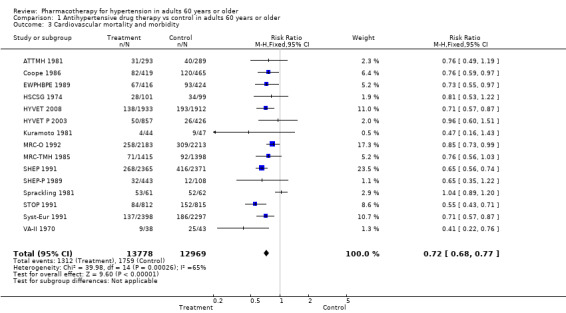

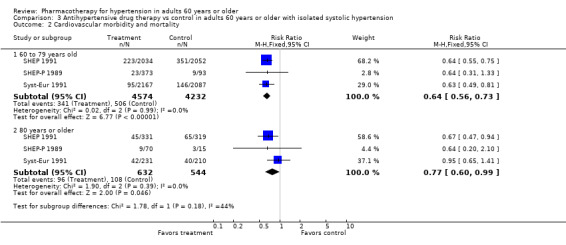

Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity (M&M)

Five studies independently reached statistical significance (HYVET 2008; MRC‐O 1992; SHEP 1991; STOP 1991; Syst‐Eur 1991).

For the 15 trials reporting cardiovascular mortality and morbidity data in people 60 years of age or older, treatment caused a significant reduction with the fixed‐effect model (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.77; participants = 26,747; studies = 15; I² = 65%) and with the random‐effects model (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.83; participants = 26,747; studies = 15; I² = 65%). See Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control in adults 60 years or older, Outcome 3 Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity.

Excluding the two studies that included TIA in the definition of the outcome measure revealed a similar reduction in overall cardiovascular mortality and morbidity (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.77) (ATTMH 1981; Coope 1986).

For subgroups, see Analysis 2.2. Investigating treatment effects between the two subgroups showed no significant difference. Tests for subgroup differences showed the following: Chi² = 0.49, df = 1 (P = 0.49), I² = 0%.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control according to subgroup (60 to 79 years old and 80 years or older), Outcome 2 Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity.

Patients 60 to 79 years old (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.77; participants = 18,484; studies = 8; I² = 45%).

Patients 80 years or older (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.87; participants = 6546; studies = 7; I² = 0%).

Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity were significantly reduced in both subgroups.

The test for subgroup differences indicates that there was no statistically significant subgroup effect (P = 0.49), suggesting that age does not modify the effect of antihypertensive treatment in comparison to placebo or no treatment. However, smaller numbers of trials and participants (seven trials in 6546 participants) contributed data to the 80 years or older subgroup than to the 60‐ to 79‐year‐old subgroup (eight trials in 18,484 participants), showing no heterogeneity between the two subgroups and 95% CI overlap.

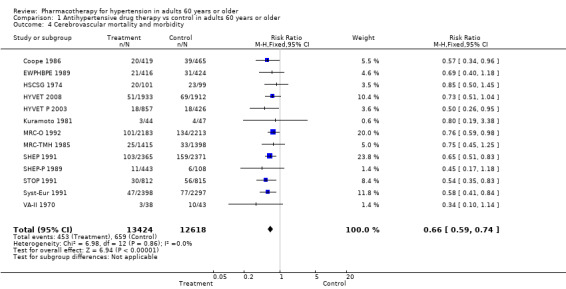

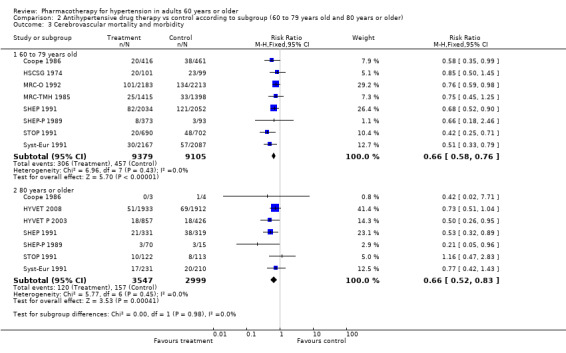

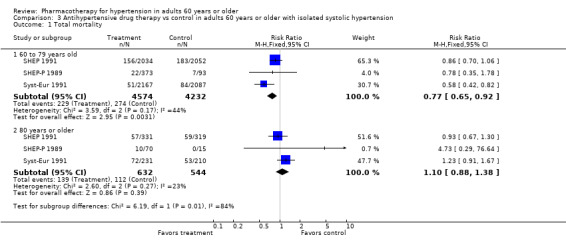

Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity

Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity were significantly reduced among patients 60 years of age or older (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.74; participants = 26,042; studies = 13; I² = 0%). See Analysis 1.4.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control in adults 60 years or older, Outcome 4 Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity.

For subgroups, see Analysis 2.3. Investigating treatment effects between the two subgroups showed no significant difference. Tests for subgroup differences showed the following: Chi² = 0.00, df = 1 (P = 0.98), I² = 0%.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control according to subgroup (60 to 79 years old and 80 years or older), Outcome 3 Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity.

Patients 60 to 79 years old (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.76; participants = 18,484; studies = 8; I² = 0%).

Patients 80 years of age or older (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.83; participants = 6546; studies = 7; I² = 0%).

Cerebrovascular mortality and morbidity were significantly reduced in both subgroups.

The test for subgroup differences indicated that there was no statistically significant subgroup effect (P = 0.98), suggesting that age does not modify the effect of antihypertensive treatment in comparison to placebo or no treatment. However, smaller numbers of trials and participants (seven trials in 6546 participants) contributed data to the 80 years or older subgroup than to the 60‐ to 79‐year‐old subgroup (eight trials in 18,502 participants), showing no heterogeneity between the two subgroups and similar 95% CIs.

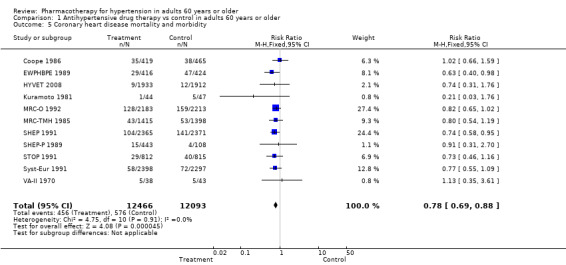

Coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity

Coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity were significantly reduced in patients 60 years of age or older (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.88; participants = 24,559; studies = 11; I² = 0%). See Analysis 1.5.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control in adults 60 years or older, Outcome 5 Coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity.

For subgroups, see Analysis 2.4. Investigating treatment effects between the 2 subgroups showed no significant difference. Tests for subgroup differences showed the following: Chi² = 0.03, df = 1 (P = 0.86), I² = 0%.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antihypertensive drug therapy vs control according to subgroup (60 to 79 years old and 80 years or older), Outcome 4 Coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity.

Patients 60 to 79 years old (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.90; participants = 18,284; studies = 7; I² = 0%): coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity were significantly reduced in the 60‐ to 79‐year‐old subgroup.

Patients 80 years or older (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.20; participants = 5263; studies = 6; I² = 0%).

The test for subgroup differences indicated that there was no statistically significant subgroup effect (P = 0.86), suggesting that age does not modify the effect of antihypertensive treatment in comparison to placebo or no treatment. However, smaller numbers of trials and participants (six trials in 5263 participants) contributed data to the 80 years or older subgroup than to the 60‐ to 79‐year‐old subgroup (seven trials in 18284 participants), showing no heterogeneity between the two subgroups and 95% CI overlap.

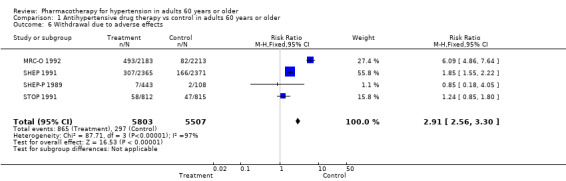

Withdrawals due to adverse effects

The numbers of participants who dropped out of trials due to adverse drug effects often were not reported. The five trials that did report these data showed a significant increase in withdrawals due to adverse effects (RR 2.91, 95% CI 2.56 to 3.30; participants = 11,310; studies = 4; I² = 97%). The effect size was significant even when MRC‐O 1992 with high risk of performance and detection bias as well as selective reporting bias was excluded from analyses (RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.45 to 2.00; participants = 6914; studies = 4; I² = 55%).

The number of people withdrawing from therapy due to adverse effects varied from study to study. On average, treating 17 participants in SHEP 1991 resulted in one withdrawal, whereas in MRC‐O 1992, treating nine participants with a diuretic and four with a beta blocker resulted in one withdrawal. In MRC‐O 1992, unblinded physicians made decisions regarding severity of side effects and continuation of therapy; 176 of those in the beta blocker group were withdrawn because of bradycardia. Withdrawal data for participant subgroups 60 to 79 years old and 80 years and older were not reported separately.

Sensitivity analyses

When we excluded studies with SBP ≥ 190 mmHg (Coope 1986; Sprackling 1981; STOP 1991), studies with observation as a control (Carter 1970; Coope 1986; HYVET P 2003), or studies with high risk of performance and detection bias (ATTMH 1981; Carter 1970; Coope 1986; HYVET P 2003; MRC‐O 1992; MRC‐TMH 1985; Sprackling 1981), the overall risk ratio for both mortality and cardiovascular mortality and morbidity was similar. Results were similar when the fixed‐effect or the random‐effects model was used. In the three trials restricted to persons with isolated systolic hypertension, reported benefits were similar.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review provides the best available evidence for antihypertensive treatment for people with elevated blood pressure who are at least 60 years of age. It is important to appreciate that the populations studied had relatively high systolic blood pressure: an average of 172/81 mmHg in the isolated systolic hypertension trials and an average of 182/95 mmHg in the other trials. The reason that diastolic blood pressure (DBP) is lower than expected is that for two trials, mean baseline DBP was 91 mmHg (HYVET 2008; MRC‐O 1992), for two trials 86 mmHg (Kuramoto 1981; Syst‐Eur 1991), and for one study 77 mmHg (SHEP 1991). DBP at baseline was not reported in two studies (Carter 1970; MRC‐TMH 1985).

In this population, antihypertensive drug treatment was associated with a modest reduction in all‐cause mortality (high‐quality evidence; risk ratio (RR) 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 0.97). This represents an absolute risk reduction (ARR) in deaths from 110 to 100 events per 1000 participants over an average duration of 3.8 years (ARR = 1%; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) = 100) (Table 1). The reduction in mortality among adults 60 years or older was due to a significant reduction in fatal stroke and in fatal myocardial infarction (MI) (Figure 4).

Cardiovascular mortality and morbidity were significantly reduced (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.77). This represents an absolute reduction from 136 to 98 events per 1000 participants for a mean duration of treatment of 3.7 years (ARR = 3.8%; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome = 27) (Table 1). This is a smaller ARR than the 4.3% reported in the first update of this review. This smaller ARR is due to the fact that we have added data from the MRC‐TMH 1985 trial, which studied patients with mild to moderate elevations in blood pressure (BP), and to the fact that we excluded transient ischaemic attack (TIA) from this outcome. The overall ARR of 3.8% as seen here is less than that found for first‐line low‐dose thiazides of 3.9%, which includes adults of all ages. To assess benefit from first‐line thiazides in adults 60 and over, we deselected all trials that did not provide first‐line thiazides. In that analysis, the effect on total cardiovascular events with first‐line thiazides in adults 60 and over from eight trials in 10,926 people was RR 0.67 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.74) with ARR 5.1% and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome = 20 over 3.7 years.