Abstract

T cell responses to symbionts in the intestine drive tolerance or inflammation depending on the genetic background of the host. These symbionts in the gut sense the available nutrients and adapt their metabolic programs to utilize these nutrients efficiently. Here, we ask whether diet can alter the expression of a bacterial antigen to modulate adaptive immune responses. We generated a CD4+ T cell hybridoma, BθOM, specific for Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B. theta). Adoptively transferred transgenic T cells expressing the BθOM TCR proliferated in the colon, colon-draining lymph node, and spleen in B. theta colonized healthy mice and differentiated into regulatory T (Treg) and effector T (Teff) cells. Depletion of B. theta-specific Tregs resulted in colitis, showing that a single protein expressed by B. theta can drive differentiation of Tregs that self-regulate Teffs to prevent disease. We found that BθOM T cells recognized a peptide derived from a single B. theta protein, BT4295, whose expression is regulated by nutrients, with glucose being a strong catabolite repressor. Mice fed a high glucose diet had a greatly reduced activation of BθOM T cells in the colon. These studies establish that the immune response to specific bacterial antigens can be modified by changes in the diet by altering antigen expression in the microbe.

One Sentence Summary:

Diet alters symbiont-specific immune responses via regulation of the expression of an outer membrane vesicle antigen.

Introduction

Dietary components and metabolites produced by host and microbial enzymes modulate the function of a variety of host immune cells including T cells (1–3). These products can have local effects on the intestinal immune system as well as more distant organs (4). For instance, host enzymes break down starch and various disaccharides in the diet to produce glucose, which is required systemically for maximal effector T (Teff) cell stimulation (5, 6). Microbial metabolites derived from dietary fiber, flavonoids, and amino acids such as tryptophan have immunomodulatory activities (3, 7–10). As examples, short chain fatty acids from fiber fermentation promote the development of intestinal regulatory T (Treg) cells (3), modulate macrophage polarization (11), and suppress innate lymphoid cell development (12). Further, tryptophan catabolites act via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor to induce T cell cytokine production (13); taurine-conjugated bile acids formed from milk-derived dietary fat induces a pro-inflammatory T helper type 1 immune response (14), and lastly, the microbial metabolite desaminotyrosine derived from flavonoids stimulates type I interferons and modulates macrophage activation and cytokine production (15). Recently, ascorbate, a microbial metabolite altered in Crohn’s disease, has been shown to modulate T cell activity (16). Other dietary components such as excess salt can change the composition of the microbiome and favor pathogenic T helper 17 (TH17) responses (17). Conversely, an iron-deficient diet can dampen intestinal inflammation (18). Collectively these studies reveal the dominant effects of dietary components and their immediate or downstream metabolites on the immune system.

CD4+ T cells play a critical role in the response to specific microbial antigens in the intestine (19–23). Symbiotic bacteria that do not damage the host produce tolerogenic Tregs responses while pathogens that cause damage elicit Teffs responses. In both cases, microbe-specific antigens drive these responses, and these intestinal bacterial are well known to be modulated by diet. However, the effect of diet on T cells that recognize these different groups of symbionts has not been tested. This latter question is of importance due to the effects of diet on the composition and physiology of the microbiome, which has a multitude of effects on the host. It is unclear if specific dietary components have effects at the level of specific bacterial antigens and the T cells that recognize them.

We hypothesize that the CD4+ immune response to specific bacterial antigens can be modified by changes in the diet through effects on antigen expression of the microbe. Progress in this area has been hampered by the lack of a model system in which a CD4+ T cell response can be examined for a specific gut symbiont. To this end, we developed a CD4+ T cell model, termed BθOM, specific for an outer membrane (OM) antigen from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (B.theta, Bθ). B. theta is a prototypic gut symbiont that degrades a wide variety of dietary, host, and microbial glycans, and is a representative of a prominent genus found in most human microbiomes (24). In healthy mice gavaged with B. theta, we found that TCR-transgenic BθOM T cells responded in vivo by differentiating into Treg and Teff cells. Deletion of the BθOM Tregs induced colitis by activated BθOM T cells, revealing that the symbiont-specific CD4+ T cells were no longer able to self- regulate to prevent T cell-mediated disease. The B. theta antigen recognized by BθOM T cells was identified to be BT4295, an outer membrane protein contained in one of B. theta’s many polysaccharide utilization loci (PUL). We found that we can modify the response of BθOM T cells to their cognate antigen by altering the salts and glycans available to B. theta. Interestingly, glucose was identified as a catabolite repressor of BT4295 expression. Mice fed a high glucose diet had greatly reduced activation of BθOM T cells, establishing a direct link between dietary regulation of a microbial antigen and CD4+ T cell activation. These results show that specific dietary components can alter the T cell driven immune response to dominant symbiotic antigens.

Results

The B. theta-specific CD4+ T cell response is sensitive to changes in B.theta growth media

To determine how dietary components and metabolites can affect the interactions between a symbiont and the host immune system, we developed a bacteria-specific CD4+ T cell model. We chose to focus our study on B. theta, a model gut symbiont that is known to adapt to changes in the available nutrients, especially by changing expression of carbohydrate utilization gene loci. We immunized C57BL/6J mice with the human B. theta strain VPI-5482 (herein referred to as B. theta) and produced T cell hybridoma cell lines that responded to B. theta. We screened the T cell hybridomas for reactivity against B. theta outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), which have been shown to be a source of antigen to the immune system (25). To identify a T cell sensitive to changes in available nutrients, we took advantage of a fortuitous observation that B. theta grown in two different formulations of TYG media—classic TYG (TYG) and modified TYG (mTYG) (Table S1)—stimulated T cells differently. We chose one T cell hybridoma clone (herein denoted as B. theta outer membrane or “BθOM”) that showed a robust response to both B. theta and OMVs in T cell stimulation assays (Fig. 1, A and B). When we cultured BθOM T cell hybridomas with bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) along with B. theta grown in the different media, BθOM T cell activation was highest with B. theta grown in TYG media (Fig. 1C); no stimulation of these T cells was observed when B. theta was grown in mTYG media (Fig. 1C). Thus, BθOM T cells were sensitive to changes in the nutrients in the media used to grow B. theta.

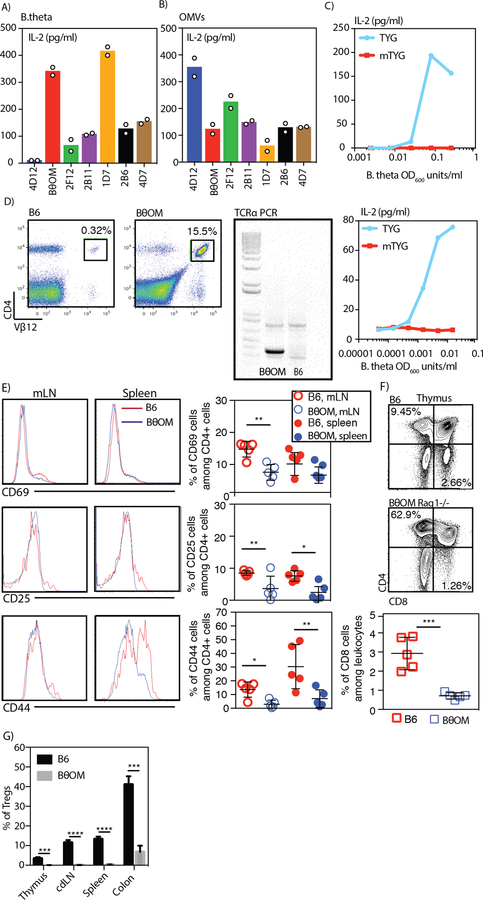

Fig. 1. Generation and characterization of the BθOM TCR transgenic mouse.

(A-B) IL-2 levels in pg/ml after generated T cell hybrid clones were cultured with BMDMs loaded with (A) B. theta (n=2, 1 experiment) or (B) OMVs (n=2, 1 experiment). (C) IL-2 levels in pg/ml after the BθOM T cell hybrid was cultured with BMDMs loaded with B. theta grown in TYG or mTYG (n=2, both replicates are shown). (D) Representative flow cytometry plot with Vβ12 staining on blood leukocytes of C57BL/6J mice (left) or BθOM transgenic mice (middle) (n=3, 3 experiments). Representative TCRα1 PCR on DNA isolated from tails of C57BL/6J mice and BθOM transgenic mice (right) (x=3, 3 experiments). (E) Representative histograms of CD69, CD25 and CD44 expression (left) and quantification of the percentage of CD69, CD25 and CD44 cells among all CD4 cells (right) isolated from the mLNs and spleen of C57BL/6J mice (red) or BθOM transgenic mice (blue) (x=5, 3 experiments). (F) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD4 and CD8 staining of thymic cells isolated from C57BL/6J mice or BθOM transgenic mice (x=5, 3 experiments) and quantification of the percentage of CD8 T cells among the thymic leukocyte population. (G) The percentage of Tregs in the thymus (n≥6, n=3 experiments), colon-draining lymph node (cdLN) (n≥10, n=6 experiments), spleen (n≥10, n=6 experiments), and colon (n=4, n=4 experiments) of C57BL/6J mice (black) or BθOM transgenic mice (gray). Student’s t test: (E) *P<0.1, **P<0.01 (F) ***P=0.0004 (G) **** P<0.0001, ***P=0.0001.

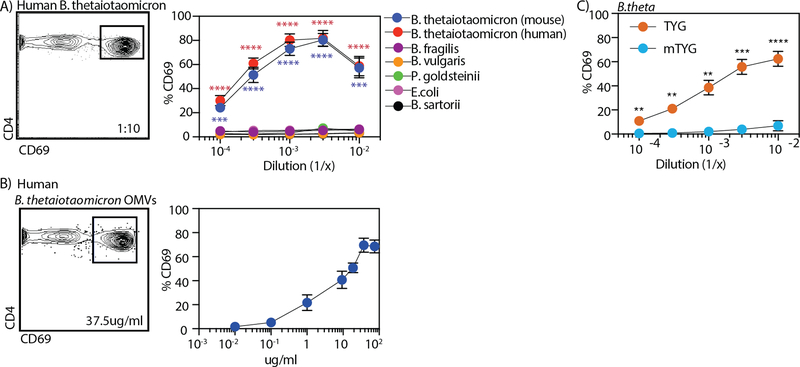

We next created a transgenic mouse line expressing the BθOM T cell receptor genes on a C57BL/6J-Rag1−/−-CD45.1 genetic background (BθOM Rag1−/− mouse strain). The TCR transgenic T cells from this line were I-Ab restricted, expressed Vα1 and Vβ12 (Fig. 1D), and were specific for B. theta (human or mouse isolates) (Fig. 2A). The peripheral T cells from BθOM Rag1−/− mice were essentially all naive, expressing low levels of CD69, CD25, and CD44 proteins (Fig. 1E); the thymus was also devoid of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1F). We found that BθOM transgenic mice develop few if any thymic or peripheral Tregs compared to non-transgenic C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 1G). Isolated naive T cells from BθOM Rag1−/− mice could be activated when stimulated in vitro with BMDM incubated with either B. theta or OMVs (Fig. 2, A and B). Stimulation of the BθOM TCRtg T cells by B. theta was confirmed to be sensitive to nutrients in TYG media (Fig. 2C), enabling the use of BθOM T cells to study the effect of diet on symbiont-host interactions.

Fig. 2. B. theta activates BθOM T cells in a nutrient-dependent manner.

(A-B) The percentage of CD69 expressing BθOM T cells after a 24-hour culture with BMDM loaded with (A) Bacteroidaceae family (human: B. thetaiotaomicron (n=4, 4 experiments); mouse: B. fragilis, B. vulgaris, P. goldsteinii, E.coli, B. sartorii (n=3, 3 experiments), or (B) human B. theta OMVs (75µg/ml: n=7, 6 experiments; 37.5µg/ml: n=6, 6 experiments; 18.75µg/ml: n=5, 4 experiments; 10µg/ml: n=8, 6 experiments; 1µg/ml: n=3, 3 experiments; 0.1µg/ml: n=4, 4 experiments; 0.01µg/ml: n=3, 3 experiments). Flow cytometry plots are gated on CD4+ CD45.1+ leukocytes. (C) the percentage of CD69 expressing BθOM hybridoma T cells after a 24-hour culture with BMDM loaded with human B. theta grown in TYG (n=13, 5 experiments) or mTYG media (n=5, 5 experiments). One-way ANOVA analysis: (A) ***P<0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Means with asterisks are significantly different by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Student’s t test: (C) **** P<0.0001, ***P=0.0001, **P<0.01.

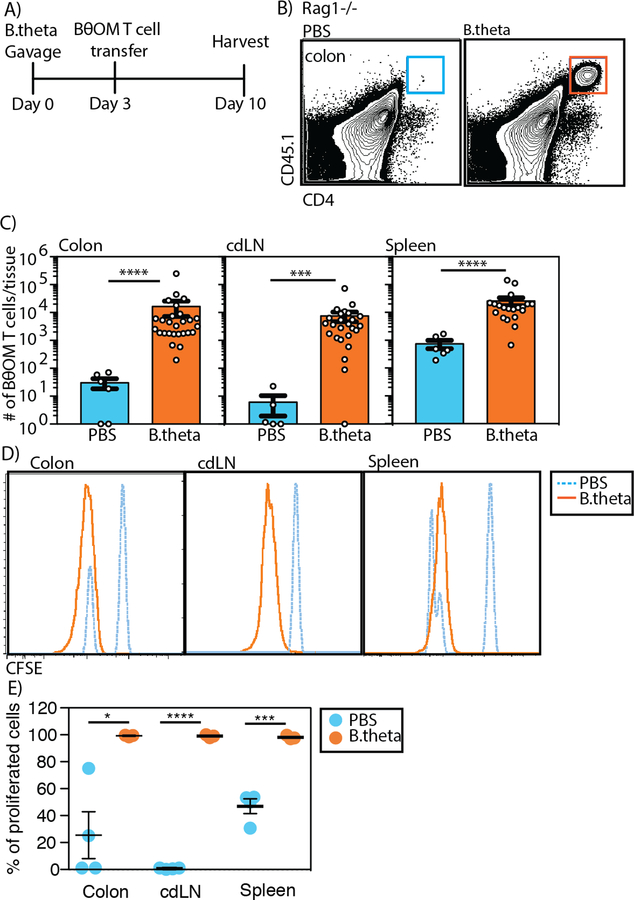

We then evaluated the function of BθOM T cells in vivo by transferring them into antibiotic pre-treated Rag1−/− mice. Mice were pre-treated with antibiotics for three weeks to allow colonization with the subsequently gavaged human-isolate of B. theta, which we previously showed colonize mice under these conditions (26). Sorted naive (CD44loCD62Lhi) CD25-CD4+CD45.1+ BθOM T cells (fig. S1A) were transferred into Rag1−/− mice that had been previously colonized by B. theta for four days (fig. S1B). We identified CD4+CD45.1+ T cells in the lamina propria, colon- draining lymph node (cdLN) or one lymph node among the mesenteric lymph nodes (mLN) that drains the colon, and spleen 7 days after T cell transfer (Fig. 3, A and B). In these mice, BθOM T cell localization in the colon lamina propria and cdLNs was dependent on B. theta colonization (Fig. 3C). We also found BθOM T cells in the spleen of B. theta colonized Rag1−/− mice (Fig. 3C). The BθOM T cells proliferated in the lamina propria, cdLN, and spleen, revealing that they were exposed to their cognate antigen (Fig. 3, D and E). B. theta gavaged BθOM Rag1−/− mice did not have obvious signs of disease such as weight loss (fig. S2A).

Fig. 3. BθOM T cells proliferate in the colon in B. theta colonized mice.

(A) Schematic of adoptive transfer of BθOM T cells into Rag1−/− mice gavaged with PBS or B. theta. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD45.1+CD4+ BθOM T cells in the colon of B. theta gavaged mice compared to PBS gavaged mice. (C) Number of BθOM T cells among live leukocytes that are CD45.2-CD45.1+CD4+ in PBS or B. theta gavaged mice in the colon (n≥6, ≥5 experiments), cdLN (n≥5, ≥3 experiments), and spleen (n≥6, ≥4 experiments). (D) Representative histograms of adoptively transferred CFSE-labeled BθOM T cells in the colon (n≥3, ≥3 experiments), cdLN (n≥3, 3 experiments), and spleen (n≥3, ≥3 experiments) of B. theta gavaged mice compared to PBS gavaged mice. (E) Quantification of the percentage of proliferated CFSE low CD45.2-CD45.1+CD4+ T cells in the colon (n≥3, ≥3 experiments), cdLN (n≥3, 3 experiments) and spleen (n≥3, ≥3 experiments). Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed data: (C)****P < 0.0001, ***P=0.0006. Student’s t test: (E) ****P < 0.0001, ***P=0.0005, *P=0.0160

BθOM T cells differentiate into Teffs and Tregs that self-regulate to prevent colitis

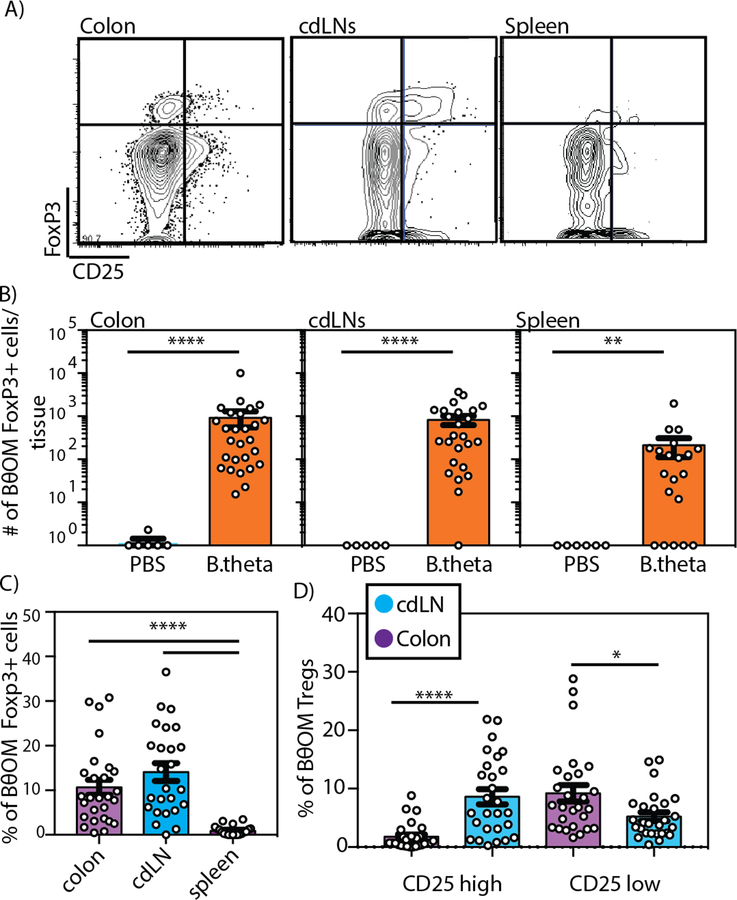

Because Bacteroides have been previously shown to be strong drivers of Treg induction (27), we reasoned that the BθOM Tregs would mediate tolerance to B. theta. We transferred BθOM T cells into Rag1−/− mice; the transferred cells were pre-sorted for CD4+CD44loCD62LhiCD25- to ensure that there was no transfer of preexisting Tregs into recipients (fig. S1A). Characterization of the BθOM T cells in multiple locations showed a mixture of Teff and FoxP3+ Treg cells in the lamina propria and cdLN with a lower percentage of Tregs found in the spleen (Fig. 4, A to C). Treg development in the peripheral lymphatics and the colonic tissue was dependent on B. theta colonization because few to no Tregs were found in PBS gavaged mice (Fig. 4B and fig. S1B). Despite the presence of Tregs in both the cdLN and colonic lamina propria, the cdLNs had many more Tregs expressing CD25 than the colon, where the majority of Tregs expressing FoxP3 lacked CD25 expression (Fig. 4D). Consistent with previous reports with polyclonal Tregs exposed to Bacteroides in the lamina propria (28, 29), 50% of BθOM FoxP3+ Tregs express RORγ t (fig. S1C). This finding is also consistent with a report showing that in healthy wild-type mice, pathobiont-specific T cells differentiate into RORγt-expressing specific iTreg cells in the large intestine (30). Together, these data reveal that the same TCR can differentiate into both Teff and Treg cells (19).

Fig. 4. BθOM T cells in the colon differentiate into Tregs.

(A) Flow cytometry plots of CD45.1+CD4+ BθOM T cells in the colon, cdLN, and spleen of PBS or B. theta gavaged Rag1−/− mice transferred with naive CD25- BθOM T cells. (B) The number of CD4+ CD45.1+FoxP3+ BθOM Tregs cells in the colon (n≥6, ≥5 experiments), cdLN (n≥5, ≥3 experiments), and spleen (n≥6, ≥4 experiments) of PBS or B. theta gavaged Rag1−/− mice after CD25- BθOM T cell transfer. (C) The percentage of FoxP3+ Tregs in the colon (n=27, 9 experiments), cdLNs (n=25, 7 experiments), and spleen (n=20, 7 experiments) of Rag1−/− mice that received naive CD25- BθOM T cells and were gavaged with B. theta. (D) The percentage of CD25high versus CD25low CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs in the colon (n=27, 9 experiments) and cdLNs (n=25, 7 experiments) of Rag1−/− mice gavaged with B. theta and injected with naive BθOM T cells. Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed data: (B)****P<0.0001, **P=0.004. Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s posttest, for non-normally distributed data: (C) ****P<0.0001. Two-way ANOVA analysis: (D) ****P<0.0001, *P=0.0161.

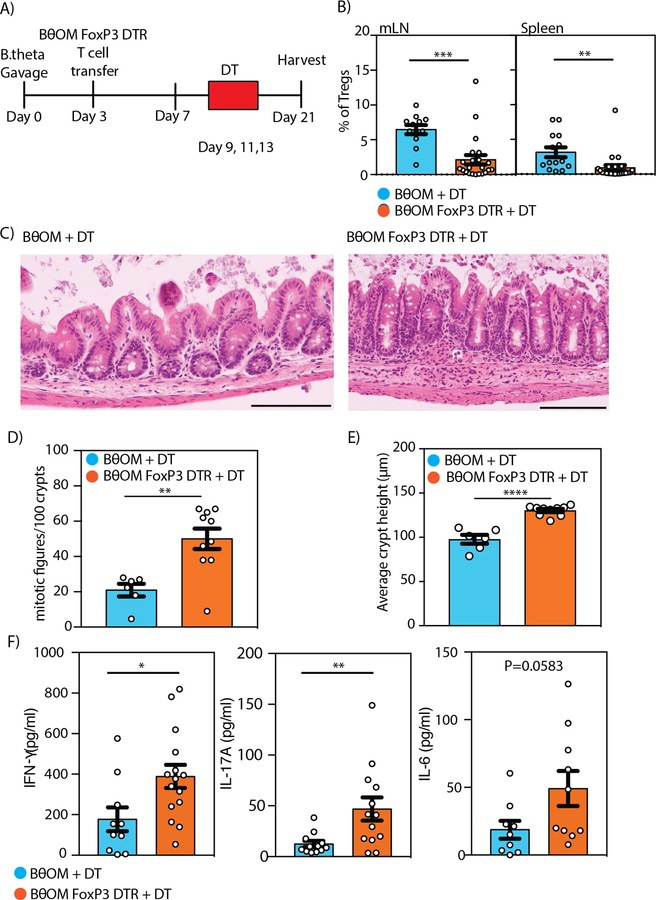

We hypothesized that B. theta-specific Tregs produced sufficient regulation in the colonic mucosa to prevent B. theta-specific CD4+ T cells from inducing colitis upon exposure to B. theta. To test this hypothesis, we crossed the BθOM transgenic mouse to FoxP3-DTR-GFP mice, which permits the in vivo depletion of Tregs upon diphtheria toxin (31) treatment and includes a GFP marker for Treg cell identification (30). We transferred naive, GFPlo BθOM T cells into Rag1−/− mice colonized with B. theta that were treated with DT on days 9, 11, and 13 (Fig. 5A). We confirmed depletion of Tregs in the cdLNs and spleen (Fig. 5B). We found that Rag1−/− mice that received BθOM-FoxP3-DTR cells and DT developed colitis, with an increase in hyperproliferative crypts, epithelial proliferation, lymphocyte infiltrate, mitotic figures, and crypt height compared to control mice that received BθOM T cells and DT (Fig. 5, C to E). Cells isolated from the mLN of Rag1−/− mice transferred with BθOM-FoxP3-DTR T cells and treated with DT to deplete Tregs showed an increase in proinflammatory cytokines (IL-17A, IFNγ, IL-6) compared to cells isolated from Rag1−/− mice receiving wild type BθOM T cells and treated with DT (Fig. 5F and fig. S3, A and B). Both BθOM-FoxP3-DTR T cells and wild type BθOM T cells isolated from the colon lamina propria and mLN differentiated into TH1 cells (fig. S4A). BθOM-FoxP3-DTR T cells can also differentiate into TH17 cells; however, variable levels of TH17 induction were observed between experiments (fig. S4, B and C). These findings are a direct demonstration that a symbiont-specific CD4+ T cell can develop into both Teff and Treg cells and that these Tregs can self-regulate.

Fig. 5. Depletion of BθOM Tregs drives BθOM CD4+ Teff to cause colitis.

(A) Schematic of adoptive transfer of BθOM or BθOM-FoxP3-DTR T cells into Rag1−/− mice gavaged with PBS or B. theta and treated with diphtheria toxin (31) to deplete BθOM Tregs. (B) Percentage of BθOM Tregs after depletion in the mLN (n≥12, 5 experiments) or spleen (n≥14, 5 experiments). (C-E) (C) Histology, (D) quantification of the number of mitotic figures/10 crypts, and (E) average crypt height in cecal sections from Rag1−/− mice given BθOM T cells and DT (n=6, 3 experiments) compared to those given BθOM-FoxP3-DTR T cells and DT (n=10, 3 experiments). Bars: 120 μm. (F) Cytometric bead array used to quantify IFNγ (n≥10, 3 experiments), IL-17A (n≥10, 3 experiments), and IL-6 (n≥10, 3 experiments) after cells isolated from the mLN were stimulated with PMA for 5 hours. Student’s t test: (B) ***P=0.0002, **P=0.0055, (D) **P=0.0029, (E) ****P<0.0001, (F) *P=0.0205, **P=0.098.

The antigen recognized by BθOM T cells, BT4295, is expressed in a polysaccharide utilization locus

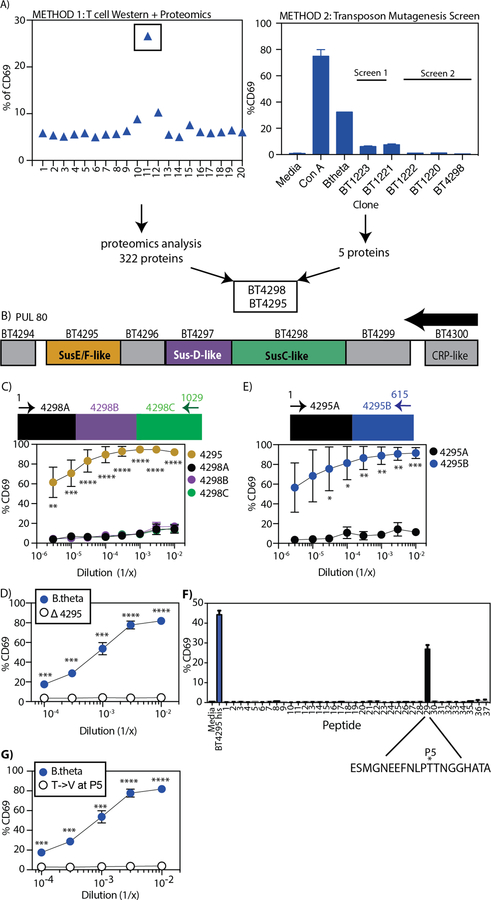

To elucidate how diet could affect a bacterial antigen expression, we needed to identify the antigen recognized by BθOM T cells. To identify this B. theta antigen, we used positive functional fractionation, mass spectrometry, and a loss-of-function screen. Using B. theta OMVs as the starting material, we performed a T cell activation assay from 20 fractions of isolated proteins separated based on molecular weight (Fig. 6A and fig. S5A). We found a single fraction of B. theta OMV proteins that stimulated BθOM T cells (Fig. 6A). Mass spectrometry analysis of this fraction identified 322 distinct proteins (Fig. 6A). To refine the list of potential antigens, we generated a B. theta transposon insertion library (32) and screened individual clones using the in vitro T cell activation assay for BθOM T cells (Fig. 6A). In a screen of 2,300 clones, we identified five genes that when knocked out no longer stimulated BθOM T cells (Fig. 6A and fig. S5B). One of the five B. theta gene candidates (BT4298) was identified in the mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 6A). The other 4 hits were all in one additional unlinked locus (BT1220–23) containing genes encoding enzymes in the pentose phosphate pathway.

Fig. 6. BθOM T cells specifically recognize the BT4295(541–554) epitope.

(A) Two parallel methods, T cell Western with Proteomics (left) and Transposon Mutagenesis (TM) (20) Screen (right), used to identify the antigen that stimulates BθOM T cells. (B) Schematic of the polysaccharide utilization locus (PUL80) affected by BT4298 disruption by TM. The arrow represents the direction of transcription. (C-G) The percentage of CD69 expressing BθOM T cells after culture with BMDM loaded with (C) E. coli expressing the full length BT4295 (n=3, 3 experiments for each dilution) or three consecutive segments of BT4298 (BT4298A, B, C) (n=3, 3 experiments for each dilution), (D) B. theta (n=4, 4 experiments) or Δ4295 (n=4, 4 experiments), or (E) E. coli expressing two consecutive segments of BT4295 (BT4295A and B) (n=3, 3 experiments for each dilution). (F) Synthetic 20-amino acid peptides overlapping by 12 amino acids. The asterisks represent the P5 position. (G) B. theta (n=4, 4 experiments, same data as Fig. 2E) or Δ4295 (n=3, 3 experiments). One-way ANOVA analysis: (C) **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. Means with asterisks are significantly different by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Student’s t test: (D) ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, (E) *P<0.1, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, (G) ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

Expression in E. coli of the BT4298 protein identified in both the mass spectrometry and transposon library, unexpectedly, did not stimulate BθOM T cells (Fig. 6C). However, many bacterial genes are organized into co-transcribed operons and this is likely to be true for B. theta. For example, the BT4294–4300 polysaccharide utilization locus (PUL) was previously shown to be coordinately activated in response to mucus O-linked glycans (26, 33). We therefore reasoned that the transposon insertion in the BT4298 gene exerts loss of function effects on downstream genes due to polarity (Fig. 6B), including BT4295, which was also identified in our mass spectroscopy analysis (Fig. 6A). Expression of BT4295 in E. coli resulted in strong stimulation of BθOM T cells (Fig. 6C), demonstrating the BT4295 was the antigen recognized by BθOM T cells. BT4295 is predicted to be a SusE/SusF lipoprotein that is ultimately trafficked to the outer membrane, including OMVs (fig. S6A) (26). We confirmed that BT4295 was the only antigen recognized by BθOM T cells by generating an in-frame deletion mutant of BT4295 that disrupted its expression (BTΔ4295), and abolished its ability to stimulate BθOM T cells (Fig. 6D).

To identify the epitope in BT4295 recognized by BθOM T cells, we expressed amino and carboxyl halves of the protein in E. coli (Fig. 6E). We found that the carboxyl half of the protein activated BθOM T cells (Fig. 6E). We then generated overlapping 20-mer peptides for the entire carboxyl half of BT4295 and tested them for their ability to activate BθOM T cells. A single peptide (536–555) stimulated BθOM T cells (Fig. 6F). The antigenic epitope was further defined to be the highly stimulatory 14-mer, (541–554) (EEFNLPTTNGGHAT), which contains a strong predicted I-Ab binding motif (P1 = F543) (fig. S6B). We identified the threonine at the P5 position (T547) to be critical for TCR recognition and generated a point mutation at the P5 position (a threonine to a valine substitution, T547V) that resulted in the complete loss of BθOM T cell activation (Fig. 6G). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that BθOM T cells strongly and specifically recognize a single peptide epitope (BT4295541–554) in the BT4295 protein, which is expressed in the B. theta outer membrane in response to mucin-type O-glycan (MOG) cues.

Expression of BT4295 is regulated by available nutrients

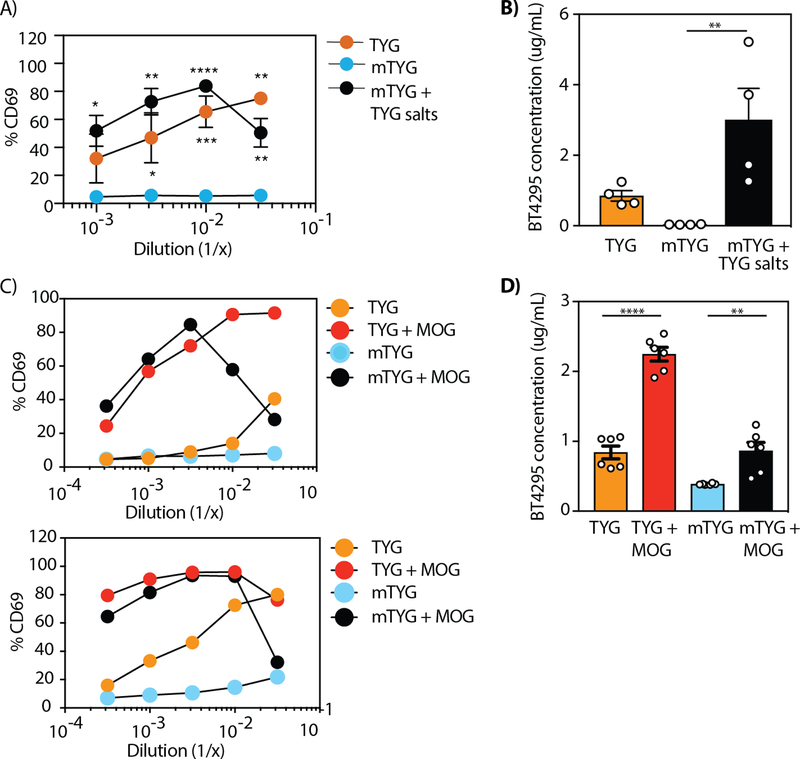

Having identified BT4295 as the antigen recognized by BθOM T cells, we determined how specific nutrients altered its expression. Based on the differential ability of B. theta grown in TYG versus mTYG media to stimulate BθOM T cells (Fig. 2C), we asked whether removing specific components (Table S1) from the TYG media or adding them to the mTYG media would alter the stimulatory ability of B. theta grown in these modified media. Individually removing vitamin B12, vitamin K3, histidine, cysteine, FeSO4, or MgCl2 from TYG media had no effect on the ability of B. theta to stimulate BθOM T cells (fig. S7, A and B). However, when we removed salts (KH2PO4, (NH2)4SO4, and NaCl) from TYG, B. theta grown in this altered media no longer stimulated BθOM T cells (fig. S7, A and B). Because removing salts from the TYG media did reduce B. theta growth to some extent, we also tested the addition of these salts to mTYG media that contained significantly lower concentration of salts (KH2PO4, K2HPO4, and NaCl) (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, adding TYG salts to mTYG media resulted in a significant increase in BθOM T cell activation (Fig. 7A). The ability of B. theta grown in TYG, mTYG, and mTYG with TYG salts to stimulate BθOM T cells directly correlated with the level of BT4295 protein expression as determined by a quantitative ELISA (Fig. 7B, fig S7C).

Fig. 7. Salt and glycan regulate BT4295 expression and alter BθOM T cell activation.

(A) The percentage of CD69 expressing BθOM T cells after a 24-hour culture with BMDM loaded with B. theta grown in mTYG (n=4, 4 experiments), TYG (n=2, 2 experiments), and mTYG supplemented with TYG salts (n=4, 4 experiments). (B) The concentration in µg/mL of BT4295 protein expressed in B. theta grown in TYG, mTYG, and mTYG supplemented with TYG salts (n=4, 4 experiments) as determined by a quantitative ELISA. (C) The percentage of CD69 expressing BθOM T cells after a 24-hour culture with BMDM loaded with B. theta grown in mTYG, TYG, mTYG supplemented with MOG, and TYG supplemented with MOG (n=2, 2 experiments). (D) The concentration in µg/mL of BT4295 protein expressed in B. theta grown in mTYG, TYG, mTYG supplemented with MOG, and TYG supplemented with MOG (n=3, 3 experiments) as determined by a quantitative ELISA. One-way ANOVA analysis: (A) *P<0.1, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, (B) ** P=0.0093, (D) ****P<0.0001, **P=0.0065. Means with asterisks are significantly different by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Previous transcriptional analysis showed that in the absence of dietary glycans, B. theta in vivo increases the expression of the BT4294–4300 PUL likely to breakdown endogenous mucin glycans, which is supported by in vitro expression of this PUL in response to purified mucin glycans (34, 35). Therefore, we tested whether growing B. theta in mTYG with porcine MOG would increase expression of BT4295 and drive BθOM T cell activation. We found that B. theta grown in mTYG supplemented with MOG now strongly activated BθOM T cells (Fig. 7C) and led to increased BT4295 protein expression (Fig. 7D). Thus, BT4295 expression can be up-regulated by MOG in mTYG media, which alone did not induce expression. Together these findings demonstrate that by changing available nutrients (salts or glycans), the expression of a specific symbiont-derived antigen can be dramatically affected.

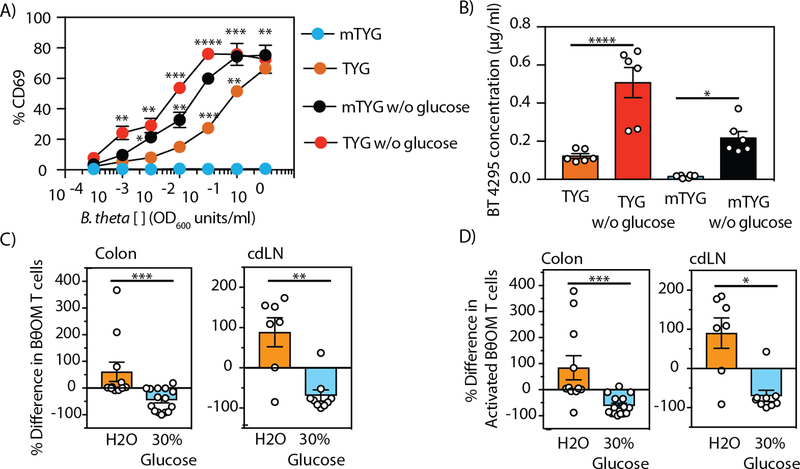

Glucose catabolitically represses BT4295

The four transposon mutants hits in the pentose phosphate pathway that significantly decreased expression of BT4295 (Fig. 6A) implicated glucose metabolism as another potential regulator of BT4295 expression. To test the involvement of glucose on regulation of BT4295 expression, we eliminated glucose from the TYG and mTYG media (Table S1). B. theta grew in both media in the absence of glucose, but at slightly reduced rates. Remarkably, we found that BθOM T cells were now stimulated by B. theta grown in mTYG in the absence of glucose (Fig. 8A). Similarly, B. theta grown in TYG without glucose also stimulated BθOM T cells, even stronger than in the presence of glucose (Fig. 8A). Thus, glucose appeared to be acting as a repressor of BT4295 expression. Catabolite repression is a well-established regulatory process in bacteria, including B. theta, in which other metabolic pathways are repressed in the presence of glucose or other high priority nutrients (36, 37). Using a quantitative ELISA for BT4295 protein, we tested if the increase in stimulatory ability of B. theta grown in the absence of glucose was due to increased BT4295 protein expression. Removing glucose from the mTYG media resulted in a 14.5-fold increase in the expression of BT4295 and removing it from TYG media resulted in a 4-fold increase (Fig. 8B). This finding again shows a direct correlation between the level of BT4295 protein expression and the ability to stimulate BθOM T cells, providing proof that glucose is acting as a repressor of BT4295 expression. From these findings we conclude that in the presence of glucose, B. theta shuts down the expression of the BT4294–4300 PUL, thereby reducing production of the BT4295 antigen.

Fig. 8. Dietary glucose represses BT4295 expression, decreasing the activation of BθOM T cells in vivo.

(A) Representative plot of the percentage of CD69 expressing BθOM T cells after culture with BMDM loaded with B. theta grown in TYG and mTYG media with or without glucose (n=6, 3 experiments). (B) The concentration in µg/mL of BT4295 protein expressed in B. theta grown in TYG and mTYG media with or without glucose (n=6, 3 experiments). The percent difference in the number of (C) CD4+CD45.1+ BθOM T cells or (D) CD4+CD45.1+CD44+CD62L- activated BθOM T cells in the colon (n=26, x=3 experiments) and cdLN (n=16, 2 experiments) of B. theta colonized mice given water or 30% glucose water and adoptively transferred with 200,000 CD4-enriched BθOM T cells. (C-D) The percent difference was calculated from the mean of each experiment. ANOVA-multiple comparison analysis: (A) *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, (B)****P<0.0001, *P=0.0190. Means with asterisks are significantly different by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed data: (C) ***P=0.0002, **P=0.0052, (D) ***P=0.0002, *P=0.0115.

Dietary glucose decreases the stimulation of BθOM T cells in vivo

We next determined if exogenous glucose affected the ability of BθOM T cells to be stimulated in vivo by decreasing BT4295 expression. We added 30% glucose to the drinking water of recipient mice and maintained them on the standard chow throughout the course of the experiment. The addition of 30% glucose to the drinking water had no effect on B. theta colonization levels (fig. S8A). Dramatically, the number of BθOM T cells in the colon and cdLN decreased in the recipient mice fed 30% glucose (Fig. 8C). Although there was no difference in Tregs (fig. S8B), the number of activated BθOM T cells was also decreased (Fig. 8D). Thus, with a high glucose diet, BT4295 antigen expression is decreased, resulting in weaker stimulation of the BθOM T cells. This finding establishes that diet can affect the expression of a specific symbiont antigen and modulate a CD4+ T cell response in vivo.

Discussion

We developed a symbiont-specific T cell model to study how diet could affect the interactions between a symbiont and the host immune system. We show that BθOM T cells respond to B. theta and OMVs, but not other Bacteroides family members. Next, we identified BT4295, a SusE/F homolog, as the BθOM T antigen. Transfer of BθOM T cells into B. theta colonized Rag1−/− mice showed that antigen-specific T cells differentiate into Tregs and Teff cells. Upon depletion of BθOM Tregs, the BθOM Teff cells cause colitis. We show that the expression of BT4295 can be altered by glycans, salts, and glucose. A high glucose diet reduced activation of the BθOM T cells, making BT4295 a nutrient-sensitive antigen able to alter T cell responses to microbes. This study definitively shows that diet can play a role in altering antigen expression thereby affecting immune responses.

TCR transgenic models have been previously developed to study antigen-specific responses to gut microbes. T cells specific for segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) in the small intestine have revealed how symbiotic microbes contribute to driving organ-specific autoimmunity (23). The CBir1 Tg T cell is widely used to study antigen-specific microbial interactions (21); however, it does not recognize its antigen during homeostasis despite the abundance of microbial antigen in the lumen (38). More recently, Helicobacter species-specific transgenic T cells were shown to respond differently during homeostasis and mucosal injury/inflammation (19, 29). In all of these cases, microbial antigens were not shown to cross the epithelial barrier except in the context of inflammation. Therefore, we developed a symbiont-specific T cell that responds to B. theta and OMVs, a relevant source of antigen that crosses the colonic epithelium and interacts with the host immune system during homeostasis (25, 39).

Though our study focused on a single T cell and its cognate antigen, this approach is likely relevant because of the concept of immunodominance. Despite a theoretically large number of potential microbial epitopes, which can be recognized by CD4+ T cells, the immune system generally focuses on a few immunodominant epitopes. As one example, the CD4+ T cell response in mice to SFB focuses on two dominant antigens of this microbe (23). We propose that the TCR we identified in this study may be specific for a dominant B. theta antigen.

Our data directly shows the conversion of a naive B. theta-specific T cell into Tregs. Using the DTR system, we deplete B. theta-specific Tregs and show that in the absence of these cells, symbiont-specific T cells cause colitis. To determine the mechanism of Treg induction, we identified the antigen driving T cell activation. Previous reports in B. fragilis identified capsular polysaccharides on OMVs that induce Tregs (40) suggesting that bacterially derived polysaccharides have immunomodulatory effects on the host immune system. Our study extends the types of Bacteroides antigens that can participate in T cell development, including induction of Tregs.

One potential factor we have not controlled for is a direct effect of glucose on T cells. There is significant literature showing that glucose enhances T cell responses (31, 41, 42). To our knowledge, there are no reported studies showing that increased glucose in vivo would decrease T cell responses or homeostatic proliferation. Although we cannot definitively rule out that increased glucose in vivo was directly inhibiting BθOM T cells, the literature supports our conclusion that increased dietary glucose caused a decrease in T cell proliferation due to a direct effect on BT4295 protein expression.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) involves a potentially definable number of chronically activated T cells and microbial antigen specificities. We now show that specific TCR/cognate antigen pairs can be modulated by altering dietary components to affect gene expression of such a key microbial antigen. Future work developing additional TCR/antigen systems from other symbionts, including those that are enriched in IBD subjects, will be valuable to test if this paradigm established with B. theta can be extended to other key microbial antigens. If glucose repression or salt stimulation of dominant microbial antigens is widespread, then such dietary manipulations may become effective for therapy.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The objective was to generate a B. theta-specific T cell system (BθOM T cells) to identify the interactions between immune system and an antigen expressed on a highly prevalent colonic symbiont and identify the role that diet plays in altering that interaction. We designed and performed experiments in cellular immunology, protein biochemistry, and mass spectrometry. The number of independent experiments is outlined in the figure legends.

Mice

All experimental procedures were performed under approval by Washington University’s Animal Studies Committee. Mice were housed in an enhanced specific pathogen-free facility. BθOM transgenic mice on the Rag1−/− background were maintained by breeding to a non-transgenic Rag1−/− mouse. BθOM-FoxP3-DTR mice were generated by breeding BθOM transgenic mice with FoxP3-DTR mice (30).

Generation of the BθOM Transgenic mouse

B. theta was grown to confluence and washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). C57BL/6J mice were immunized subcutaneously in the rear footpads with B. theta mixed with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Difco) in a 1:1 ratio. One week later, draining popliteal lymph nodes were harvested and stimulated in vitro with B. theta for 3 days. Stimulated T cells were fused following a standard protocol. Hybridomas were selected for responsiveness to B. theta presented by IFN-γ stimulated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM). The BθOM clone was selected for further analysis and its T cell receptor genes sequenced and cloned into TCR expression vectors (43). TCRα and β constructs were coinjected into C57BL/6J pronuclei in the Washington University Department of Pathology and Immunology’s Transgenic Core Facility. Transgenic mice were identified by PCR amplification of the Vα1 and Vβ12 transgenes from tail DNA (Vα1 forward primer GTTTCCAAGCAGGTGTGAGGAG and reverse primer CAAAACGTACCAGGGCTTACC; Vβ12 forward primer CTTCTCTTCTAGGTGATGCTG and reverse primer CCCAGCTCACCGAGAACAGTC)

Antibodies and Reagents

The following reagents were purchased from BD Biosciences: CD62L (MEL-14), CD45.1 (A20); Biolegend: CD4 (GK1.5), CD69 (H1.2F3), CD45.1 (A20), CD44 (IM7), CD25 (PC61), CD45.2 (104), CD25 (PC61), Vβ12 (MRII-I), Mouse TH1/TH2/TH17 Cytometric Bead Array Kit; eBiosciences: CD25 (eBio3C7), CD4 (RM4–5), FoxP3 (FJK-16s), IFNγ (XMG1.2), and IL-17A (TC11–18H10.1); Life Technologies: CellTrace CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit, LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit; Roche: DNase1 from bovine pancreas grade II; Sigma: Collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum. Homemade cocktail antibodies for negative selection of CD4+ T cells were purchased from Tombo: anti-mouse Ter-119, CD11c (clone N418), CD11b (M1/70), CD8α (53–6.7), CD19 (1D3), and CD45R/B220 (RA3–6B2); Biolegend: CD49b (DX5), CD24 (M1/69); Miltenyi Biotec: anti-biotin microbeads.

Media recipes

TYG medium:

BD Bacto: 10g/L tryptone, 5g/L yeast extract; Sigma: 4g/L D-glucose, 100mM KH2PO4, 8.5mM (NH2)4SO4, 15mM NaCl, 10µM Vitamin K3, 2.63µM FeSO4•7H2O, 0.1mM MgCl2, 1.9µM hematin, 0.2mM L-histidine, 3.69nM Vitamin B12, 413µM L-cysteine; Mallinckrodt: 7.2µM CaCl2•2H2O.

mTYG medium:

BD Bacto: 20g/L tryptone, 10g/L yeast extract: Sigma: 5g/L D-glucose, 8.25mM L-cysteine, 78µM MgSO4•7H2O, 294µM KH2PO4, 230µM K2HPO4, 1.4mM NaCl, 7.9µM Hemin (hematin), 4µM Resazurin, 24µM NaHCO3; Mallinckrodt: 68µM CaCl2•2H2O.

Preparation of OMVs

B. theta OMVs were purified with multiple rounds of centrifugation and filtering. (25)

Functional in vitro macrophage-T cell assay

BMDM were stimulated with IFN-γ at 2,000 U/ml in I-10 media (IMDM, 10% FBS, glutamine and gentamicin) and plated on a 96-well plate at 1×105 cells per well. The cells were washed with PBS 24 hours later and kept in 100µl of fresh I-10 media without IFN-γ for another 24 hours. 5×105 splenocytes or 1×105 isolated BθOM CD4+ T cells were added per well in 50µl with 50µl of half log dilutions of Bacteroidaceae strains and OMV. Bacteroidetes were grown in a 5mL TYG or mTYG culture at 37°C overnight to mid-log phase. Cultures were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in media prior to adding to the assay. 24 hours later, the supernatant containing the T cells was transferred to a fresh 96-well plate and spun down at 1200rpm. The cells were washed with FACS buffer and stained for CD69 expression.

In vivo experiments

Bacterial stocks:

Bacteroidetes were grown anaerobically from single isolates in standing culture in TYG at 37°C for 24 hours (33). Each culture was concentrated by centrifugation, mixed with sterile, pre-reduced PBS and glycerol to a final concentration of 20% glycerol, and frozen at −80°C in single-use aliquots.

Gavage:

Rag1−/− mice were placed on antibiotics at 3–4 weeks of age for 3–4 weeks. Antibiotic treatment consisted of 0.66mg/ml ciprofloxacin, 2.5mg/ml metronidazole (Sigma), and 20mg/ml sugar-sweetened grape Kool-Aid Mix (Kraft Foods) in the drinking water (44). Mice were gavaged with 100μl of antibiotic water on the first 2 days and the last 2 days of the 3–4 week duration. For the bulk of the experiments, mice were taken off antibiotic water and given Kool-Aid. For the in vivo glucose experiments, mice were taken off antibiotic water and given water or 30% glucose water. Two days later mice were gavaged with 100μl of B. theta strains at a concentration of 1×108 CFU/ml. Fecal pellets were obtained on day 0, 4, and 7 to determine colonization.

BθOM T cell transfer:

Three days after gavage, Rag1−/− mice were injected with BθOM T cells isolated from the peripheral lymph nodes (axillary, brachial, and inguinal), mesenteric lymph nodes, and spleen. Cells were enriched by negative selection using a homemade cocktail of antibodies (see reagents) and sorted for CD4+CD44loCD62LhiCD25- T cells. 1–2×105 cells were injected retrorbitally.

Lamina propria dissociation:

Seven days after T cell transfer, mice were sacrificed and leukocytes were isolated from the lamina propria following the Lamina Propria Dissociation Kit protocol published by Miltenyi Biotec.

Peripheral tissue processing:

The colon draining lymph node (cdLN) and spleen were removed and processed using frosted microscope slides (Fisher Scientific). Samples were filtered through a 70μm filter.

Diphtheria toxin depletion of BθOM FoxP3+ Tregs

Treg depletion:

Antibiotic treated Rag1−/− mice were gavaged with B. theta and injected with enriched and sorted 1×105 BθOM-FoxP3-DTR or BθOM T cells. Intraperitoneal injections of diphtheria toxin (10µg/kg) were performed on days 9, 11, and 13 post gavage. Depletion was confirmed by staining for Tregs on day 21 post gavage in mLNs and spleen.

Cytokines:

On day 21 post gavage, 5×104 mLNs and 2×106 splenocytes were stimulated with PMA (50ng/ml) and ionomycin (500ng/ml) for 5 hours at 37°C. TH1/TH2/TH17 cytokines were quantified in the supernatant using the BD™ Cytometric Bead Array following the manufacturer’s instructions. Supernatants from splenocytes samples were diluted 1:2.

T cell differentiation:

On day 24 post gavage, cells isolated from the colon lamina propria and mLN were stimulated with PMA (50ng/ml) and ionomycin (500ng/ml) for 1 hour at 37°C, Brefeldin A was added (5µg/ml), and the cells were stimulated for 4 additional hours at 37°C. TH1 and TH17 cells were identified by intracellular staining with IFNγ and IL-17A antibodies.

Tissue Harvest, Fixation, and Preparation for Histology

Ceca and colons were fixed in methacarn for 12–16 hours at 24°C. Samples were washed with 100% methanol for 30 min x 2, followed by 100% ethanol for 20 min x 2 and then stored in 70% ethanol. 5μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H+E). Representative images of cecal histology were taken with an Olympus BX51 microscope. Blinded microscopic analysis for mitotic figures using H+E-stained histologic sections was performed at 20X magnification on well-oriented crypts as previously described (44).

Fecal Bacterial DNA extraction and qPCR amplification

Fecal bacterial DNA extraction and qPCR amplification was performed according to a previously published protocol (25, 45).

T cell Western Assay

B. theta OMV antigens were separated using a T cell Western blot assay as described (46). Briefly, 500µg of OMVs were separated on a 10% SDS PAGE gel on both left and rights sides of the gel with molecular weight standards on both sides. For the left side, the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose, each lane cut into 20 strips, dissolved in DMSO, and precipitated with sodium carbonate/sodium bicarbonate. The nitrocellulose particles from each strip was tested for their ability to stimulate BθOM T cells using BMDM as APCs. The corresponding position of the active fraction on the right side of the SDS-PAGE gel were further analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Proteomic analysis of OMVs

Proteomic analysis of the corresponding T cell stimulatory SDS-PAGE fraction of OMVs from TYG grown B. theta was performed using standard procedures at MS Bioworks, Ann Arbor, MI. Briefly, the gel slices were digested with trypsin and analyzed by nano LC-MS/MS with a Waters NanoAcquity HPLC system interfaced to a ThermoFisher Q Exactive. The data were searched using Mascot against the UniProt B. theta reference proteome. Mascot DAT files were parsed into Scaffold for validation, filtering, and to create a non-redundant list per sample, requiring at least two unique peptides per protein.

B. thetaiotaomicron Transposon Mutagenesis Library and Screen

Transposon mutagenesis of B. theta was performed as described previously (32). Briefly, mutagenesis was carried out on an Acapsular B. theta strain (ΔCPS) lacking all capsular polysaccharide loci, which was previously characterized (37). Here, we used the pSAM_Bt vector containing mariner transposon and an ermG cassette. S17 E. coli was used to deliver the vector through conjugative transfer into B. theta. DNA isolation from selected mutants was performed using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit. Two-round PCR was performed to identify the transposon insertion site with the following conditions: round 1; 1 cycle at 95°C (3 min); 5 cycles 95°C (30 sec), 30°C (30 sec), 72°C (45 sec); 32 cycles at 95°C (30 sec), 55°C (30 sec), 72°C (45 sec). The PCR reactions from step 1 were purified using a Qiagen PCR Purification Kit and 100–200ng of product was used as template for round 2; 1 cycle at 95°C (3 min); 35 cycles at 95°C (30 sec), 55°C (30 sec), 72°C (45 sec). Reactions from round 2 were run on a 2% Agarose-TBE gel and bands were extracted using the Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit. These products were then sequenced using the primers previously described (32).

The library was frozen in 96-well plates. The plates were thawed, spun down and the media was removed, washed 1X in 200µl PBS then suspended in 100µl complete media. 10µl of each was screened using the in vitro macrophage-T cell assay during the primary screen and hits were retested in duplicate for conformation before sequencing.

Generation of the BT4295 mutant

BT4295 gene deletion and amino acid substitutions within this gene were done using allelic exchange as described previously (47). Briefly, all manipulations were done in a Δtdk strain background of B. theta using the pExchange-tdk vector (48) and primers listed in Table S2. All Bacteroides strains and mutants were grown in TYG medium or brain-heart infusion agar with 10% horse blood added. Antibiotics were used as needed: gentamicin (200µg/ml), erythromycin (25µg/ml), and 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (200µg/ml).

Generation of the BT4295 T->V mutant

Construction of the T547V mutation was done using site-directed mutagenesis via overlapping PCR. Forward and reverse primers were synthesized containing the desired mutation and outside primers were constructed to contain the entire BT4295 gene. Once a verified construct was sequenced as containing the mutation, we followed a similar strategy to construct the deletion mutants (e.g. 4295 or SPdeletion). E. coli containing the T547V construct were mated with the BT4295 deletion strain, therefore complementing the BT4295 gene back, but with a T547V mutation so that it no longer stimulated T cells.

Expression of BT4295 and BT4298 in E. coli

To express BT4295 and BT4298 in E. coli, we use the Lucigen Expresso™ T7 Cloning and Expression System and followed the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, we expressed BT4295 and BT4298 in the pETite N-His Kan vector and designed oligonucleotides for cloning full length or partial proteins listed in Table S2.

Sequence confirmed clones of each were transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli and grown overnight at 37°C with shaking. Fresh 2ml cultures were inoculated and grown to an OD600 of 0.5, induced with 1mm IPTG and grown for 5 hours at 37°C with shaking, harvested by centrifugation, washed once with PBS, and suspended in 1ml PBS. Samples were heat inactivated for 20 min at 95°C, then stored at 4°C until use.

Production of recombinant BT4295

BT4295 was expressed in Pet-ite expression vector by cloning the sequence distal to the SPII cleavage motif and including a 5’ 6 His tag using the oligos CATCATCACCACCATCACTCGCCCGATTACGAAACCGAGTT (forward) and GTGGCGGCCGCTCTATTATATACTGCAGTTAAATGCCTAG (reverse) (49). The construct was verified by sequencing and expressed in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3). Bacteria were grown 37°C until mid-log phase growth was reached. The culture was induced with 1mM IPTG and grown overnight at 19°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation, lysed (50mM NaH2PO4, 300mM NaCl, 10mM imidazole, 1mg/ml lysozyme (HEL), and protease inhibitors at pH 8.0) for 30 minutes on ice, sonicated, and centrifuged to remove insoluble material. Supernatants were passed over a Qiagen NiNTA column, washed and eluted in 50mM NaH2PO4, 300mM NaCl, 250mM imidazole, and protease inhibitors at pH 8.0. Eluted material was buffer exchanged into PBS with an Amicon Ultra 15, 10kDa concentrator to 1–2ml final volume and quantified by A280.

Generation of monoclonal antibodies against BT4295

C57BL/6J mice were immunized subcutaneously with 100µg of recombinant protein (rBT4295) emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) and boosted twice with 100µg of rBT4295 in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) every four weeks, followed by an IV boost of 50µg rBT4295 three days prior to harvest. Splenic B cells were fused with P3Ag8.6.5.3 myeloma cells to create hybridomas. Hybridomas were screened by ELISA against rBT4295, and positives were screened against whole B. theta or OMV preparations to confirm specificity. Two clones (ERC-11 and 4E9) were selected for further characterization. They were subcloned by limit dilution, and both antibodies isotyped as IgG2b,κ. The antibodies were purified from culture supernatants on a Protein A-Sepharose column. Purified 4E9 was biotinylated using the Pierce Ez-Link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin reagent following the manufacturers protocol.

Quantitative ELISA for BT4295

BT4295 protein levels in B. theta samples were determined using a quantitative ELISA assay. Samples were obtained from equivalent numbers of B. theta from OD600 measured cultures. Bacteria were lysed in 100mM CHAPS detergent (Sigma) and incubated with agitation for 1 hour at RT. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation and samples were stored at 4°C. Purified anti-BT4295 antibody, ERC11, was coated on Immunolon 2 ELISA plate overnight at 5µg/ml in pH 9.6 carbonate coating buffer at 4°C. Plates were washed and blocked with buffer (PBS with 0.5% BSA and 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 hour at RT. Plates were washed and samples were added for 2 hours at RT, washed again, and then 5µg/ml of the anti BT4295 antibody biotin-4E9 was added for 1.5 hours at RT. Plates were washed again and 1:5000 dilution of streptavidin HRP (Southern Biotech) was added for 1 hour RT. Plates were washed and developed with ABTS to completion and A405 determined. Unknown sample concentrations were quantitated by comparison to a standard curve of rBT4295 performed in the same ELISA using GraphPad Prism software.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between two groups were evaluated using Student’s t test (or Mann-Whitney test, for non-normally distributed data) and those among more than two groups were evaluated using ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (or Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s posttest for non-normally distributed data) using GraphPad Prism. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be significant. Data are summarized as means ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Sorting strategy and B. theta colonization for in vivo BθOM T cell transfer experiments.

Fig. S2. BθOM T cells do not cause weight loss in B. theta colonized mice.

Fig. S3. Cytokines not altered by BθOM Treg depletion.

Fig. S4. Identification of the epitope recognized by BθOM T cells.

Fig. S5. BθOM T cells recognize BT4295(541–554) and schematic of the BT4295 PUL.

Fig. S6. The effect of various nutrients on BθOM T cell activation.

Fig. S7. The effect of various nutrients on BθOM T cell activation.

Fig. S8. The addition of 30% glucose to the drinking water has no effect on B. theta colonization or Treg differentiation.

Table S1. Composition of TYG vs mTYG media.

Table S2. BT4295 and BT4298 Primers.

Table S3. Raw data.

Acknowledgments:

We thank D. Kreamalmeyer and H. Jung for animal care and breeding, E. Lantelme and D. Brinja for help with sorting, D. Stewart and T. Tolley for help with histology.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants T32AI007163 (M.M.W), F30DK114950 (S.A.H.) and by RO1DK097079 (P.M.A., E.C.M., and T.S.S.).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and Materials Availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. The BθOM TCRtg mouse strain is available to interested investigators upon request.

References and Notes

- 1.Khalili H, Chan SSM, Lochhead P, Ananthakrishnan AN, Hart AR, Chan AT, The role of diet in the aetiopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 10.1038/s41575-018-0022-9, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinewietfeld M, Manzel A, Titze J, Kvakan H, Yosef N, Linker RA, Muller DN, Hafler DA, Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature 496, 518–522 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, Glickman JN, Garrett WS, The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 341, 569–573 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ, Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 336, 1268–1273 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacIver NJ, Michalek RD, Rathmell JC, Metabolic regulation of T lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol 31, 259–283 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei J, Raynor J, Nguyen TL, Chi H, Nutrient and Metabolic Sensing in T Cell Responses. Front. Immunol 8, 247 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang PV, Hao L, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R, The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, 2247–2252 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T, Takahashi M, Fukuda NN, Murakami S, Miyauchi E, Hino S, Atarashi K, Onawa S, Fujimura Y, Lockett T, Clarke JM, Topping DL, Tomita M, Hori S, Ohara O, Morita T, Koseki H, Kikuchi J, Honda K, Hase K, Ohno H, Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 504, 446–450 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, Ward RE, Martin RJ, Lefevre M, Cefalu WT, Ye J, Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes 58, 1509–1517 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiko GE, Ryu SH, Koues OI, Collins PL, Solnica-Krezel L, Pearce EJ, Pearce EL, Oltz EM, Stappenbeck TS, The Colonic Crypt Protects Stem Cells from Microbiota-Derived Metabolites. Cell 165, 1708–1720 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji J, Shu D, Zheng M, Wang J, Luo C, Wang Y, Guo F, Zou X, Lv X, Li Y, Liu T, Qu H, Microbial metabolite butyrate facilitates M2 macrophage polarization and function. Sci. Rep 6, 24838 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JS, Cella M, McDonald KG, Garlanda C, Kennedy GD, Nukaya M, Mantovani A, Kopan R, Bradfield CA, Newberry RD, Colonna M, AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat. Immunol 13, 144–151 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cervantes-Barragan L, Chai JN, Tianero MD, Di Luccia B, Ahern PP, Merriman J, Cortez VS, Caparon MG, Donia MS, Gilfillan S, Cella M, Gordon JI, Hsieh CS, Colonna M, Lactobacillus reuteri induces gut intraepithelial CD4(+)CD8alphaalpha(+) T cells. Science 357, 806–810 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devkota S, Wang Y, Musch MW, Leone V, Fehlner-Peach H, Nadimpalli A, Antonopoulos DA, Jabri B, Chang EB, Dietary-fat-induced taurocholic acid promotes pathobiont expansion and colitis in Il10−/− mice. Nature 487, 104–108 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steed AL, Christophi GP, Kaiko GE, Sun L, Goodwin VM, Jain U, Esaulova E, Artyomov MN, Morales DJ, Holtzman MJ, Boon ACM, Lenschow DJ, Stappenbeck TS, The microbial metabolite desaminotyrosine protects from influenza through type I interferon. Science 357, 498–502 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang YL, Rossetti M, Vlamakis H, Casero D, Sunga G, Harre N, Miller S, Humphries R, Stappenbeck T, Simpson KW, Sartor RB, Wu G, Lewis J, Bushman F, McGovern DPB, Salzman N, Borneman J, Xavier R, Huttenhower C, Braun J, A screen of Crohn’s disease-associated microbial metabolites identifies ascorbate as a novel metabolic inhibitor of activated human T cells. Mucosal Immunol 10.1038/s41385-018-0022-7, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Wilck N, Matus MG, Kearney SM, Olesen SW, Forslund K, Bartolomaeus H, Haase S, Mahler A, Balogh A, Marko L, Vvedenskaya O, Kleiner FH, Tsvetkov D, Klug L, Costea PI, Sunagawa S, Maier L, Rakova N, Schatz V, Neubert P, Fratzer C, Krannich A, Gollasch M, Grohme DA, Corte-Real BF, Gerlach RG, Basic M, Typas A, Wu C, Titze JM, Jantsch J, Boschmann M, Dechend R, Kleinewietfeld M, Kempa S, Bork P, Linker RA, Alm EJ, Muller DN, Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature 551, 585–589 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kortman GA, Mulder ML, Richters TJ, Shanmugam NK, Trebicka E, Boekhorst J, Timmerman HM, Roelofs R, Wiegerinck ET, Laarakkers CM, Swinkels DW, Bolhuis A, Cherayil BJ, Tjalsma H, Low dietary iron intake restrains the intestinal inflammatory response and pathology of enteric infection by food-borne bacterial pathogens. Eur. J. Immunol 45, 2553–2567 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chai JN, Peng Y, Rengarajan S, Solomon BD, Ai TL, Shen Z, Perry JSA, Knoop KA, Tanoue T, Narushima S, Honda K, Elson CO, Newberry RD, Stappenbeck TS, Kau AL, Peterson DA, Fox JG, Hsieh CS, Helicobacter species are potent drivers of colonic T cell responses in homeostasis and inflammation. Sci Immunol 2, 10.1126/sciimmunol.aal5068 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu H, Khosravi A, Kusumawardhani IP, Kwon AH, Vasconcelos AC, Cunha LD, Mayer AE, Shen Y, Wu WL, Kambal A, Targan SR, Xavier RJ, Ernst PB, Green DR, McGovern DP, Virgin HW, Mazmanian SK, Gene-microbiota interactions contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Science 352, 1116–1120 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO, A dominant, coordinated T regulatory cell-IgA response to the intestinal microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 19256–19261 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, Tanoue T, Imaoka A, Itoh K, Takeda K, Umesaki Y, Honda K, Littman DR, Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 139, 485–498 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Torchinsky MB, Gobert M, Xiong H, Xu M, Linehan JL, Alonzo F, Ng C, Chen A, Lin X, Sczesnak A, Liao JJ, Torres VJ, Jenkins MK, Lafaille JJ, Littman DR, Focused specificity of intestinal TH17 cells towards commensal bacterial antigens. Nature 510, 152–156 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonnenburg JL, Xu J, Leip DD, Chen CH, Westover BP, Weatherford J, Buhler JD, Gordon JI, Glycan foraging in vivo by an intestine-adapted bacterial symbiont. Science 307, 1955–1959 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hickey CA, Kuhn KA, Donermeyer DL, Porter NT, Jin C, Cameron EA, Jung H, Kaiko GE, Wegorzewska M, Malvin NP, Glowacki RW, Hansson GC, Allen PM, Martens EC, Stappenbeck TS, Colitogenic Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron Antigens Access Host Immune Cells in a Sulfatase-Dependent Manner via Outer Membrane Vesicles. Cell Host Microbe 17, 672–680 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martens EC, Chiang HC, Gordon JI, Mucosal glycan foraging enhances fitness and transmission of a saccharolytic human gut bacterial symbiont. Cell Host Microbe 4, 447–457 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sefik E, Geva-Zatorsky N, Oh S, Konnikova L, Zemmour D, McGuire AM, Burzyn D, Ortiz-Lopez A, Lobera M, Yang J, Ghosh S, Earl A, Snapper SB, Jupp R, Kasper D, Mathis D, Benoist C, Individual intestinal symbionts induce a distinct population of RORgamma(+) regulatory T cells. Science 349, 993–997 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohnmacht C, Park JH, Cording S, Wing JB, Atarashi K, Obata Y, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Marques R, Dulauroy S, Fedoseeva M, Busslinger M, Cerf-Bensussan N, Boneca IG, Voehringer D, Hase K, Honda K, Sakaguchi S, Eberl G, The microbiota regulates type 2 immunity through RORgammat(+) T cells. Science 349, 989–993 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu M, Pokrovskii M, Ding Y, Yi R, Au C, Harrison OJ, Galan C, Belkaid Y, Bonneau R, Littman DR, c-MAF-dependent regulatory T cells mediate immunological tolerance to a gut pathobiont. Nature 554, 373–377 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY, Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat. Immunol 8, 191–197 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang CH, Qiu J, O’Sullivan D, Buck MD, Noguchi T, Curtis JD, Chen Q, Gindin M, Gubin MM, van der Windt GJ, Tonc E, Schreiber RD, Pearce EJ, Pearce EL, Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell 162, 1229–1241 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodman AL, McNulty NP, Zhao Y, Leip D, Mitra RD, Lozupone CA, Knight R, Gordon JI, Identifying genetic determinants needed to establish a human gut symbiont in its habitat. Cell Host Microbe 6, 279–289 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjursell MK, Martens EC, Gordon JI, Functional genomic and metabolic studies of the adaptations of a prominent adult human gut symbiont, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, to the suckling period. J. Biol. Chem 281, 36269–36279 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benjdia A, Martens EC, Gordon JI, Berteau O, Sulfatases and a radical S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet) enzyme are key for mucosal foraging and fitness of the prominent human gut symbiont, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. J. Biol. Chem 286, 25973–25982 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martens EC, Lowe EC, Chiang H, Pudlo NA, Wu M, McNulty NP, Abbott DW, Henrissat B, Gilbert HJ, Bolam DN, Gordon JI, Recognition and degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides by two human gut symbionts. PLoS Biol 9, e1001221 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorke B, Stulke J, Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 6, 613–624 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers TE, Pudlo NA, Koropatkin NM, Bell JS, Moya Balasch M, Jasker K, Martens EC, Dynamic responses of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron during growth on glycan mixtures. Mol. Microbiol 88, 876–890 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hand TW, Dos Santos LM, Bouladoux N, Molloy MJ, Pagan AJ, Pepper M, Maynard CL, Elson CO 3rd, Belkaid Y, Acute gastrointestinal infection induces long-lived microbiota-specific T cell responses. Science 337, 1553–1556 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bloom SM, Bijanki VN, Nava GM, Sun L, Malvin NP, Donermeyer DL, Dunne WM Jr., Allen PM, Stappenbeck TS, Commensal Bacteroides species induce colitis in host-genotype-specific fashion in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Host Microbe 9, 390–403 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL, An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell 122, 107–118 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cham CM, Driessens G, O’Keefe JP, Gajewski TF, Glucose deprivation inhibits multiple key gene expression events and effector functions in CD8+ T cells. Eur. J. Immunol 38, 2438–2450 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho PC, Bihuniak JD, Macintyre AN, Staron M, Liu X, Amezquita R, Tsui YC, Cui G, Micevic G, Perales JC, Kleinstein SH, Abel ED, Insogna KL, Feske S, Locasale JW, Bosenberg MW, Rathmell JC, Kaech SM, Phosphoenolpyruvate Is a Metabolic Checkpoint of Anti-tumor T Cell Responses. Cell 162, 1217–1228 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ho WY, Cooke MP, Goodnow CC, Davis MM, Resting and anergic B cells are defective in CD28-dependent costimulation of naive CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med 179, 1539–1549 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang SS, Bloom SM, Norian LA, Geske MJ, Flavell RA, Stappenbeck TS, Allen PM, An antibiotic-responsive mouse model of fulminant ulcerative colitis. PLoS Med 5, e41 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nava GM, Stappenbeck TS, Diversity of the autochthonous colonic microbiota. Gut Microbes 2, 99–104 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holsti MA, Allen PM, Processing and presentation of an antigen of Mycobacterium avium require access to an acidified compartment with active proteases. Infect. Immun 64, 4091–4098 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larsbrink J, Zhu Y, Kharade SS, Kwiatkowski KJ, Eijsink VG, Koropatkin NM, McBride MJ, Pope PB, A polysaccharide utilization locus from Flavobacterium johnsoniae enables conversion of recalcitrant chitin. Biotechnol Biofuels 9, 260 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koropatkin NM, Cameron EA, Martens EC, How glycan metabolism shapes the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 10, 323–335 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cameron EA, Maynard MA, Smith CJ, Smith TJ, Koropatkin NM, Martens EC, Multidomain Carbohydrate-binding Proteins Involved in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron Starch Metabolism. J. Biol. Chem 287, 34614–34625 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Sorting strategy and B. theta colonization for in vivo BθOM T cell transfer experiments.

Fig. S2. BθOM T cells do not cause weight loss in B. theta colonized mice.

Fig. S3. Cytokines not altered by BθOM Treg depletion.

Fig. S4. Identification of the epitope recognized by BθOM T cells.

Fig. S5. BθOM T cells recognize BT4295(541–554) and schematic of the BT4295 PUL.

Fig. S6. The effect of various nutrients on BθOM T cell activation.

Fig. S7. The effect of various nutrients on BθOM T cell activation.

Fig. S8. The addition of 30% glucose to the drinking water has no effect on B. theta colonization or Treg differentiation.

Table S1. Composition of TYG vs mTYG media.

Table S2. BT4295 and BT4298 Primers.

Table S3. Raw data.