Abstract

Purpose

Shared decision making is an approach where physicians and patients collaborate to make decisions based on patient values. This requires eliciting patients’ preferences for each treatment attribute before making decisions; a structured process for preference elicitation does not exist in hand surgery. We tested the feasibility and usability of a ranking tool to elicit patient preferences for the treatment of trigger finger. We hypothesized that the tool would be usable and feasible at the point of care.

Methods

Thirty patients with a trigger finger without prior treatment were recruited from a hand surgery clinic. A preference elicitation tool was created that presented 3 treatment options (surgical release, injection, and therapy and orthosis) and described attributes of each treatment extracted from literature review (eg, success rate, complications). We presented these attributes to patients using the tool and patients ranked the relative importance (preference) of these attributes to aid in their decision making. The System Usability Scale and tool completion time were used to evaluate usability and feasibility, respectively.

Results

The tool demonstrated excellent usability (System Usability Scale: 88.7). The mean completion time was 3.05 minutes. Five (16.7%) patients chose surgery, 20 (66.7%) chose an injection, and 5 (16.7%) chose therapy and orthosis. Patients ranked treatment success and cost as the most and least important attributes, respectively. Twenty-nine (96.7%) patients were very to extremely satisfied with the tool.

Conclusions

A preference elicitation tool for patients to rank treatment attributes by relative importance is feasible and usable at the point of care. A structured process for preference elicitation ensures that patients understand the trade-offs between choices and can assist physicians in aligning treatment decisions with patient preferences.

Clinical relevance

A ranking tool is a simple, structured process physicians can use to elicit preferences during shared decision making and highlight trade-offs between treatment options to inform treatment, choices.

Keywords: Patient-centered care, preference elicitation, shared decision making, trigger finger

TRIGGER FINGER RESULTS FROM entrapment of the flexor tendon at the A1 pulley.1 Trigger finger, one of the 2 most common hand conditions in a hand surgeon’s clinic,2 has a 2% to 3% lifetime incidence3 that ranges to up to 10% in diabetics.4 Several treatment options exist and, although nonsurgical measures are typically the initial treatment, no standard protocol exists.1 A 2018 Cochrane review was unable to recommended one treatment over the others.5 As such, multiple treatments for the condition are available.6 Patient-centered care for a condition that has multiple treatment options is best delivered when care is directed toward a patient’ s values and preferences for the attributes of each treatment option.

Shared decision making (SDM) is a collaborative approach used to inform the decision-making process by accounting for patient preferences and evidence-based practice. Multiple frameworks exist to implement SDM.7,8 For example, the SHARE approach, developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, includes advice to: (1) seek your patient’ s participation, (2) help your patient explore and compare treatment options, (3) assess your patient’s values and preferences, (4) reach a decision with your patient, and (5) evaluate your patient’ s decision.9 Prior work shows that SDM improves patient confidence,10,11 compliance,12 and participation in their treatment,11 and increases patient satisfaction with their visit.10 Patients also prefer taking an active role in their decision making through an SDM approach.13–15 Web sites, videos, and information sheets are often used to educate patients and help them explore treatment options; however, these “decision aids” focus on education, do not include a process to help patients assess their preferences, and can be biased and difficult to understand.16 For example, a decision aid includes the pros and cons of each option, without a process to help the patient decide how important each attribute is when considered in the context of each patient’ s circumstances. Currently, no standard process to help patients prioritize their preferences for treatment attributes exists, despite extensive work demonstrating the complexity of decision making in the setting of competing attributes.10,12,17,18

As patient-centered care becomes increasingly emphasized, a process to elicit patient preferences at the point of care is needed. As such, there are efforts to develop tools helping patients rank their preferences for competing treatment attributes. For example, a ranking tool allows patients to evaluate attributes of treatment options in the same context and rank each attribute relative to others to identify what is most/least important.19,20 Conjoint analysis is another method that allows a patient to evaluate his or her willingness to accept trade-offs between multiple treatment attributes together.19,21–23 In other specialties, these tools are used to assist patients in clarifying their preferences for urethral strictures,24 psoriasis,25 hepatitis C,26 and prostate cancer screening.20 Preference elicitation using conjoint analysis has been studied in hand surgery in hospital selection for carpal tunnel release27 and in the importance of treatment attributes in patients with a theoretical nondisplaced scaphoid waist fracture.28 The aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and usability of a ranking preference elicitation tool used at point of care (in real time) for the treatment of trigger finger.

METHODS

Tool creation

Approval for the study was obtained through the institutional review board. We first reviewed the literature and identified 6 attributes of care that patients would rank using the tool: success rate of treatment, rate of complications, immobilization time, pain with treatment, use of anesthesia, and cost of treatment. These attributes were discussed for each of 3 treatment options: (1) hand therapy and orthosis, (2) corticosteroid injection, and (3) open surgical release of the A1 pulley. The attributes were listed in an interactive, tablet-based (ipad, Apple, Cupertino, CA) ranking tool that provided background information on trigger finger, and then listed the attributes of treatment. We used the available evidence to inform a conversation between the surgeon and patient regarding each of the 6 attributes (eg, success rate) and their respective levels (eg, 50% success rate) for each attribute based on literature review and clinical practice patterns (Table 1).2,5,29–41 After discussion of the attributes and their levels for each treatment, the patients rank the attributes in order of importance using the tool (Qualtrics Research Software, Provo, UT). This approach has been used in prior studies.11,19,20,22 The ranking profile was then used to inform a collaborative discussion on which treatment best aligned with the patient’s preferences. The complete ranking tool (Figure A1, available on the Journal’s Website at www.jhandsurg.org) can also be accessed at http://med.stanford.edu/s-voices/tools.html.

TABLE 1.

Tool Creation

| Attribute | Levels | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Success rate | T: ~73%38,39

I: 45% to 84%28–30,31 S: 97% to 100%32,33 |

• Success rate was typically defined as the absence of subsequent injections or surgical release,28 complete resolution of symptoms for the entirety of follow-up29

• There is significant variation in definition of and follow-up for success rate of surgery in the literature. This review does not differentiate between digit involved or comorbid factors |

| Complication rate | T: Rare to none39

I: 0% to 1.6%29‘30 S: 3% to 37% (major: 3%, minor: 28%)27,34 |

• Primary reported complication of therapy is stiffness (up to 27%) that “resolved quickly”39 • Most common complications of injections include cellulitis,30 steroid flare, fat necrosis36 • Most common complications of surgery include major: synovial fluid cyst requiring excision, arthrofibrosis; minor: wound complications, stiffness, pain27 |

| Immobilization time | T: nightly for ~3–9 wk I: none S: none |

• Levels based on literature review demonstrating a range of immobilization from 3 to 9 wk in the therapy group37 |

| Pain associated with treatment | T: + I: ++ S: +++ |

• There is significant variation in definition and follow-up of pain associated with treatment in the literature5,27,35 |

| Treatment cost | T: $ $ I: $ S: $ $ $2 |

• Cost was discussed relative to other levels. When available, this discussion was put into the context of a patient’s remaining deductible |

| Anesthesia use | T: none I: none S: local or MAC + local |

• Levels based on literature review and general practice patterns6 |

I, injection; S, open surgical release; T, therapy and orthosis.

Patient selection

Patients recruited to participate represented a convenience sample of those presenting to the hand clinic and diagnosed with a trigger finger by the senior author. Inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older, no prior history of immobilization, therapy, injections, or surgery for the finger, and English literacy. Thirty patients were included based on prior recommendations for feasibility studies and as we did not anticipate a large variability in response data.42–45

Data collection

A fellowship-trained hand surgeon (RNK) presented the preference elicitation tool, explained the options and relevant literature, and participants used the tool to rate their preferences for attributes accordingly. The tool was presented with an iPad using a “rank order” question on web-based Qualtrics Research Software (Figure A1). After using the tool and deciding treatment, the surgeon left the room and a research coordinator administered a follow-up survey. We assessed usability of the tool via the validated System Usability Scale, a questionnaire scored from 0 to 100 in which a score of 68 or above indicates above average usability.46,47 We assessed feasibility by recording the time to complete the tool (excluding the informed consent process for study inclusion and for surgery or injection when these options were picked). Prior studies evaluating decision aids have demonstrated time to completion ranging from 8 minutes 46 seconds up to 1 hour.10,20,22,48,49 We used 8.5 minutes as a cutoff for feasibility based on prior work and the practice pattern of a busy hand surgery practice (5–10 patients per hour). At the end of the clinic visit, patients were asked (1) their level of satisfaction with the tool and (2) if the tool correctly helped identify their treatment choice, each on a 1–10 ordinal scale (1 being extremely unsatisfied or strongly disagree and 10 being extremely satisfied or strongly agree, respectively).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used for the System Usability Scale score (usability) and time to complete the tool (feasibility). We reported the number of each attribute that patients ranked as most important. We calculated each participant’s first, second, and third important attribute and reported this as a percentage of the frequency with which each attribute was rated in that specific rank. We reported the frequency with which each attribute was ranked in an individual patient’s top 3 preferences. We analyzed the frequency with which each attribute was ranked in an individual’ s top 3 preferences distributed by treatment choice. We reported level of satisfaction as a percentage.

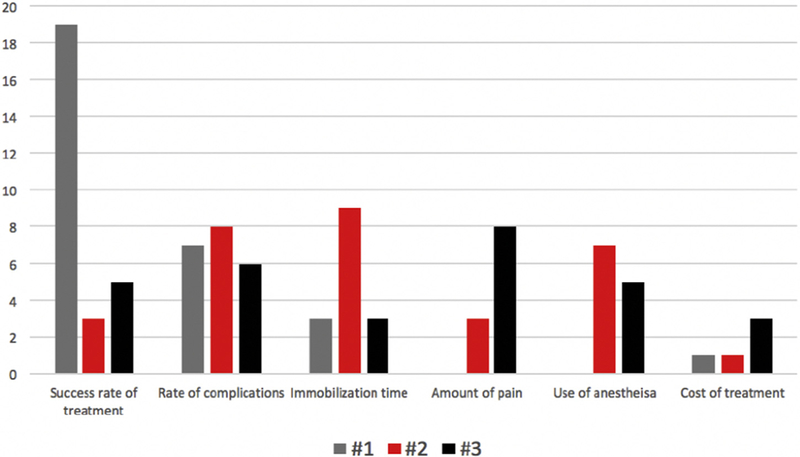

RESULTS

Thirty patients completed the preference elicitation tool and associated questions during the study period (Table 2). The mean patient age was 60.5 years (SD ± 12.3). Of 30 patients, 13 (43%) were female. The average System Usability Scale score was 88.7 (SD ±13.2). The average completion time was 3.05 minutes (±SD 0.70). Five (16.7%) patients chose surgical release, 20 (66.7%) patients chose an injection, and 5 (16.7%) patients chose therapy and orthosis. Nineteen (59.4%) patients ranked success rate of treatment as the most important attribute (Fig. 1). The attributes most and least strongly affecting patients’ decision-making process were the success rate of the treatment and the cost of treatment, respectively (Table 3). Attributes most strongly influencing patients’ treatment decisions were different for each treatment decision. Ninety-seven percent of patients were “very” or “extremely” satisfied with the tool. Ninety-three percent of patients felt that the tool correctly helped identify their treatment choice.

TABLE 2.

Demographics

| Therapy | Injection | Surgery | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 5 | 20 | 5 | 30 |

| Male/female | 3/2 | 10/10 | 4/1 | 17/13 |

| Mean age (y) | 52.4 | 62.5 | 60.6 | 60.5 |

FIGURE 1:

Total times each attribute was ranked 1, 2, and 3. Cumulative number of times each attribute was ranked most important to third most important by a patient. Patients value different attributes of treatment options.

TABLE 3.

Overall Ranking

| Ranking |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attribute | Most important | 2nd most important | 3rd most important | Percentage in top 3 |

| Success rate | 63.3% | 23.3% | 10.0% | 96.7% |

| Complication rate | 10.0% | 26.7% | 26.7% | 63.3% |

| Immobilization time | 16.7% | 20.0% | 10.0% | 46.7% |

| Pain associated with treatment | 3.3% | 3.3% | 30.0% | 36.7% |

| Anesthetic use | 6.7% | 13.3% | 16.7% | 36.7% |

| Treatment cost | 0% | 13.3% | 6.7% | 20.0% |

DISCUSSION

Prior studies have demonstrated that patients with hand and upper extremity conditions desire to be a part of the decision-making process.13,15 As health care delivery transitions toward a more patient-centered approach, tools that assist patients in making decisions that align with their values and preferences will be necessary. Currently, decision aids are primarily tailored to improve patient education about their condition and treatment options, and do not include a structured process to help patients understand their preferences for the attributes of care, understand how these preferences align with each treatment option, and assess the trade-offs between multiple treatment options. For example, patient A may prefer the treatment with the highest success rate regardless of risk, whereas patient B may prefer the least risky treatment option regardless of its success rate. Previous studies have demonstrated that the use of decision aids and preference elicitation tools improves patients’ ability to express their treatment preference,11,24 increase patient satisfaction with their visit,10 and improve patients’ confidence in,10,11 and compliance with, their decision.12 An additional advantage of a ranking preference tool as part of a decision aid is the potential to improve utilization of physician time, decrease counterproductive clinic time (eg, improve appropriateness of patient questions and decrease repetition), and shorten the overall clinic visit, thereby leading to more appropriate utilization of health care services.10,12 Our study shows that a ranking preference tool is usable and feasible in a busy hand and upper extremity clinic, and that patients are satisfied with the tool.

Patient-centered care not only increases a patient’ s understanding of their condition and treatment options, but also improves time management, as shown by our measurement of feasibility (time to complete tool).50–53 Previous studies using decision aids have recorded a mean completion time of 8 minutes 46 seconds to up to 1 hour.10,20,48,49 A systematic review of conjoint analyses concluded that tool completion time was not consistently reported and highlighted that tool implementation within a clinic workflow is a barrier to implementation.22 Conversely, Bozic et al,10 in a randomized controlled trial, implemented a decision aid tool in a joint reconstruction clinic and, despite noting that patients reported higher confidence in the questions asked, found no significant difference in total consultation time or face-to-face time with the surgeon. Although no standard time has been predetermined to conclude that a tool is feasible, and although complexity of a condition may affect what time commitment is acceptable (eg, decision for heart transplant vs trigger finger surgery), the time to completion in this study could make it potentially operational in a busy hand clinic setting. Use of the tool may potentially save time by streamlining discussions with patients and preventing patient confusion and repetition of information, although further studies are needed.

Success rate, immobilization time, and complication rates were the most influential factors in decision making. The cost of treatment and use of anesthesia were the 2 least influential factors. Shammas et al28 identified cost as the most important attribute in the relative importance of treatment attributes through the use of a conjoint analysis tool in individuals asked about a hypothetical nondisplaced scaphoid waist fracture. The importance of cost in that study may be secondary to using people without the condition (not patients) who are not dealing with their own insurance plans and deductibles or due to the difference in hand conditions studied. The sample size and single-surgeon nature of our study limit the generalizability of any conclusions regarding variables (eg, age) that may be associated with certain ranking profiles. Future work using the ranking tool could be focused on understanding these relationships and developing tailored educational tools that are directed toward certain ranking profiles for common hand conditions.

Our study has limitations. Although we conducted a thorough review of attributes that may play a role in patients’ treatment decisions and attempted to quantify levels of each attribute, there are undoubtedly attributes that affect patient decisions that were not included in the tool (eg, time away from work, number of physician visits after index visit), and additionally, there is variability in clinical practice with regard to levels of various attributes (eg, success and complication rates, exact immobilization time, cost of treatment). Furthermore, there is significant variation in levels of attributes as defined and studied in the literature (eg, injection solution, definition of success rate, type of immobilization used). An inherent limitation in the study design was also the potential effect that a surgeon may have on a patient during the decision-making process. Although the tool could be reviewed on a computer without the surgeon, the authors believe that the inclusion of a surgeon in the discussion is more reflective of actual clinical practice. It is likely that a surgeon’s bias may be minimized through the use of the tool as it refers directly to objective data and engages and empowers patients to use their preferences to inform their treatment. Nonetheless, the potential bias from a single-surgeon study, as well as our small sample size, limits the external validity of this study. As this was a feasibility and usability study, patients were surveyed only at their index visit; further follow-ups to evaluate the effects of the tool on patient-reported outcomes are needed. Despite these limitations, the advantage of the preference elicitation tool is that it can be tailored to advances in the literature and surgeon-specific practice patterns. Future studies, with a larger sample size and longer follow-up times using the ranking preference tool, as well as other methods of preference elicitation, are needed to understand and inform patient decisions in hand surgery. Lastly, we included only English-speaking patients. This may exclude cultural preferences that are limited to those who do not speak English; however, after determining proof of concept, the tool may be expanded for use in other languages.

Considering these limitations, we found that a ranking preference elicitation tool is both feasible and usable at the point of care for patients being treated for trigger finger. In addition, the tool identified attributes on which individual patients make treatment decisions and elucidated differences in the importance assigned to various attributes between treatment choices. Although the preference elicitation tool does not supplant a discussion with patients, it may serve to engage and empower patients to make decisions aligned with their preferences and make the trade-offs between various treatment choices more apparent.

Supplementary Material

Web-based ranking tool that patients used to rank aspects of treatment, in order of importance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Makkouk AH, Oetgen ME, Swigart CR, Dodds SD. Trigger finger: etiology, evaluation, and treatment. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(2):92–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerrigan CL, Stanwix MG. Using evidence to minimize the cost of trigger finger care. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(6):997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strom L Trigger finger in diabetes. J Med Soc N J. 1977;74(11): 951–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stahl S, Kanter Y, Karnielli E. Outcome of trigger finger treatment in diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 1997;11(15):287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiorini HJ, Tamaoki MJ, Lenza M, Gomes Dos Santos JB, Faloppa F, Belloti JC. Surgery for trigger finger. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD009860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pruzansky JS, Goljan P, Lundmark DP, Shin EK, Jacoby SM, Osterman AL. Treatment preferences for trigger digit by members of the American Association for Hand Surgery. Hand (NY). 2014;9(4): 529–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3): 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Youm J, Chenok K, Belkora J, Chan V, Bozic KJ. The emerging case for shared decision making in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(20):1907–1912. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The SHARE Approach. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/index.html. Accessed April, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bozic KJ, Belkora J, Chan V, et al. Shared decision making in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(18):1633–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraenkel L, Rabidou N, Wittink D, Fried T. Improving informed decision-making for patients with knee pain. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(9):1894–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klifto K, Klifto C, Slover J. Current concepts of shared decision making in orthopedic surgery. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10(2):253–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dardas AZ, Stockburger C, Boone S, An T, Calfee RP. Preferences for shared decision making in older adult patients with orthopedic hand conditions. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(10):978–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, Moskowitz MA. Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy: decision making and information-seeking preferences among medical patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(1):23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huetteman HE, Shauver MJ, Nasser JS, Chung KC. The desired role of health care providers in guiding older patients with distal radius fractures: a qualitative analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(4): 312–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ottenhoff JSE, Kortlever JTP, Teunis T, Ring D. Factors associated with quality of online information on trapeziometacarpal arthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(10):889–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hageman MG, Döring AC, Spit SA, Guitton TG, Ring D. Assessment of decisional conflict about the treatment of trigger finger, comparing patients and physicians. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2016;4(4): 353–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The New England Journal of Medicine—Catalyst. Shared decision making: time to get personal. 2017. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/shared-decision-making/. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 19.Pignone MP, Brenner AT, Hawley S, et al. Conjoint analysis versus rating and ranking for values elicitation and clarification in colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pignone MP, Howard K, Brenner AT, et al. Comparing 3 techniques for eliciting patient values for decision making about prostate-specific antigen screening: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(5):362–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1530–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weernink MGM, van Til JA, Witteman HO, Fraenkel L, IJzerman MJ. Individual value clarification methods based on conjoint analysis: a systematic review of common practice in task design, statistical analysis, and presentation of results. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(6):746–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris CA, Shauver MJ, Yuan F, Nasser J, Chung KC. Understanding patient preferences in proximal interphalangeal joint surgery for osteoarthritis: a conjoint analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(7): 615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hampson LA, Allen IE, Gaither TW, et al. Patient-centered treatment decisions for urethral stricture: conjoint analysis improves surgical decision-making. Urology. 2017;99:246–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kromer C, Schaarschmidt ML, Schmieder A, Herr R, Goerdt S, Peitsch WK. Patient preferences for treatment of psoriasis with biologicals: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2015;10(6): e0129120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mühlbacher AC, Bridges JFP, Bethge S, et al. Preferences for anti-viral therapy of chronic hepatitis C: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(2):155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim WL, Kim JS, Lee JB, Kim SH, Min DU, Park HY. Survey of preferences in patients scheduled for carpal tunnel release using conjoint analysis. Clin Orthop Surg. 2017;9(1):96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shammas RL, Mela N, Wallace S, Tong BC, Huber J, Mithani SK. Conjoint analysis of treatment preferences for nondisplaced scaphoid fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(7):678.e1–678.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Will R, Lubahn J. Complications of open trigger finger release. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(4):594–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wojahn RD, Foeger NC, Gelberman RH, Calfee RP. Long-term outcomes following a single corticosteroid injection for trigger finger. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(22):1849–1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castellanos J, Muñoz-Mahamud E, Domínguez E, Del Amo P, Izquierdo O, Fillat P. Long-term effectiveness of corticosteroid injections for trigger finger and thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(1): 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maneerit J, Sriworakun C, Budhraja N, Nagavajara P. Trigger thumb: results of a prospective randomised study of percutaneous release with steroid injection versus steroid injection alone. J Hand Surg Br. 2003;28(6):586–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marks MR, Gunther SF. Efficacy of cortisone injection in treatment of trigger fingers and thumbs. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(4): 722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benson LS, Ptaszek AJ. Injection versus surgery in the treatment of trigger finger. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22(1):138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turowski GA, Zdankiewicz PD, Thomson JG. The results of surgical treatment of trigger finger. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22(1):145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruijnzeel H, Neuhaus V, Fostvedt S, Jupiter JB, Mudgal CS, Ring DC. Adverse events of open A1 pulley release for idiopathic trigger finger. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(8):1650–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dierks U, Hoffmann R, Meek MF. Open versus percutaneous release of the A1-pulley for stenosing tendovaginitis: a prospective randomized trial. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2008;12(3):183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen RL, Søndergaard M, Lange J. Open surgery versus ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection for trigger finger: a randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(5):359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amirfeyz R, McNinch R, Watts A, et al. Evidence-based management of adult trigger digits. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2017;42(5): 473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarbai K, Hannah S, von Schroeder HP. Trigger finger treatment: a comparison of 2 splint designs. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;37(2): 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans RB, Hunter JM, Burkhalter WE. Conservative management of the trigger finger: a new approach. J Hand Ther. 1988;1(2):59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10(2):307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Browne RH. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat Med. 1995;14(17):1933–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sim J, Lewis M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of prevision and efficacy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(3):301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Julious SA. Issues with number needed to treat. Stat Med. 2005;24(20):3233–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brooke J SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, eds. Usability Evaluation in Industry. London: CRC Press; 1996:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis JR, Sauro J. The factor structure of the system usability scale In: Kurosu M, ed. Human Centered Design. HCD 2009. Berlin: Springer; 2009:94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Achaval S, Fraenkel L, Volk RJ, Cox V, Suarez-Almazor ME. Impact of educational and patient decision aids on decisional conflict associated with total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(2):229–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller KM, Brenner A, Griffith JM, Pignone MP, Lewis CL. Promoting decision aid use in primary care using a staff member for delivery. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(2):189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menendez ME, Parrish RC, Ring D. Health literacy and time spent with a hand surgeon. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(4):e59–e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ishikawa H, Hashimoto H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y, Takayama T, Yano E. Patient contribution to the medical dialogue and perceived patient-centeredness. An observational study in Japanese geriatric consultations. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):906–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teunis T, Thornton ER, Jayakumar P, Ring D. Time seeing a hand surgeon is not associated with patient satisfaction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(7):2362–2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin CT, Albertson GA, Schilling LM, et al. Is patients’ perception of time spent with the physician a determinant of ambulatory patient satisfaction? Arch Intern Med. 2011;161(11):1437–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web-based ranking tool that patients used to rank aspects of treatment, in order of importance.