Abstract

Neurons of the sparsely populated nervous system of the tadpole larva in the tunicate Ciona intestinalis, a chordate sibling, are known from sporadic previous studies but especially two recent reports that document the connectome of both the central and peripheral nervous systems at EM level. About 330 CNS cells comprise mostly ciliated ependymal cells, with ~180 neurons that constitute about 50 morphologically distinguishable types. The neurons reveal various chordate characters amid many features that are idiosyncratic. Most neurons are ciliated and lack dendrites, some even lack an axon. Synapses mostly form en passant between axons, and resemble those in basal invertebrates; some are dyads and all have heterogenous synaptic vesicle populations. Each neuron has on average 49 synapses with other cells; these constitute a synaptic network of unpredicted complexity.

Introduction

Complete connectomes provide a substrate for hypothesis generation with respect to both circuits and cell identities. For many years, only the nervous system of the nematode C. elegans [1] was known at the level of its synaptic circuits, the sole connectome [2] having the synaptic connections of all its neurons, and the neurons themselves, compiled at electron microscopic (EM) level. The initial report from the adult hermaphrodite, derived from pre-digital technology [1,3], is now supplemented by a second connectome for the adult male [4].

Recently, a complete connectome has been reported for a second, quite different species, the tadpole larva of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis [5,6], often loosely considered a chordate C. elegans because of its comparable numerical complexity. But in fact, this simple member of the largest group of marine tunicates is far removed in its ancestry from C. elegans, an ecdysozoan more closely related to Drosophila. Instead Ciona is a member of the chordate phylum and is part of the sibling group of all vertebrates [7]. Like many members of its group, Ciona is a filter-feeding adult which liberates externally fertilized gametes that after fertilization each give rise to a tiny free-living, so-called tadpole larva [8,9]. The embryo producing this larva undergoes determinate, radial cleavages for about 18 h to produce the larva, with a dorsal central nervous system (CNS) [8]. The latter comprises in succession: a rostral brain ganglion, a caudal motor ganglion and a caudal nerve cord [6,10,11].

The larval connectome: a new resource

Three tadpole larvae of Ciona, the sibling progeny of a single fertilization, have been reported to exhibit a CNS complement of 331–339 cells [12]. A fourth unrelated larva had similar overall cell numbers, of which 177 are neurons and the remainder are ependymal cells. Ependymal cells abut and line the neural canal, have cilia that project into its lumen, and are non-neuronal. EM revealed these to comprise at least 25 different types and 52 subtypes [6]. Unlike more extensively characterized nervous systems most ascidian larval neurons are known only from morphological criteria. Some of the 52 subtypes are not entirely discrete, however, so as to be distinguishable by all morphological features. Even so, the number of classes is still considerable for this tiny constituency of neurons, and compares to the 118 classes reported among the 302 neurons in C. elegans [1]. As a result, with an arithmetic average of 2–3 cells per class in Ciona, the different classes of neurons range in size from 1 (for the single antenna- coronet relay neuron) to 13 coronet cells (see below) on the left-hand side and 23 Group I photoreceptors on the right (Figure 1; Table 1). The distribution of neuron numbers and types of these per class reflects the marked asymmetry of the brain vesicle [6], which will not be considered further here. Most numerous amongst neurons are the 37 photoreceptors, of three different types: 30 ocellus pigment-cup associated photoreceptors, 18–23 in group I and 8–11 in group II [6,13], with a further group of 7 Group III photoreceptors having outer segments that are less well organized [6].

Figure 1.

Histogram of the rank-ordered numbers of cells per identified type, showing the many classes having only a single representative, and the distribution of those with more.

Table 1.

Colour-coded cell types of the larval nervous system in the ascidian tadpole of Ciona.

| Cell Type | Alternative names | Abbreviation | Defining Characteristics | Reports in the literature | Putative Neurotransmitter | Subtypes | Number of cells | Cell IDs | Example: Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I Photoreceptors | Pigmented ocellus Photoreceptors | PR-I | Outer segments into ocellus pigment | [31]; [12]; [32]; [33]; [34]; [13]; [28]; [6] | Glutam ate | outer segment projection: osa (anterior), osd (dorsal), osp (posterior); Layers i-v: I-i, I-ii, I-iii I-iv, I-v | 23 | prl-pr23 |  |

| Group II Photoreceptors | Pigmented ocellus Photoreceptors; Type II Photoreceptors; Canal photoreceptors | PR-II | Outer segments directly into neural canal near ocellus pigment | [13]; [28] ;[6] | GABA | outer segment projection: osa (anterior), osd (dorsal), osp (posterior), Layers i-ii: II-i, II-ii | 7 | pra-prg |  |

| Group III Photoreceptors | Non-pigmented ocellus photoreceptors, Type III photoreceptors | PR-III | Ventral vacuolated cells between Cor and lens cells with modified cilia into neural canal | [13]; [35]; [28] ;[6] | - | 6 | lens 6–7, 84, 101, 110, 114 |  |

|

| Lens Cells | Lens | Large, vacuolated cells ventral to ocellus pigment | [36]; [37]; [12]; [38] | round, cup | 3 | lens4, lens5, lens8 |  |

||

| Photoreceptor associated vacuolated neurons | photoreceptor associated neurons | vacIN | Anterior vacuolated neurons with short axons along photoreceptor axon tract | [6] | GABA | terminal depth: lens1, lens2 | 2 | lensl, lens2 |  |

| Photoreceptor tract interneuron | trIN | Large neuron dorsal to photoreceptors on right side, axon descending along photoreceptor tract, large expanded terminal in PBV | [13] ;[6] | Glutam ate | - | 1 | 36 |  |

|

| Antenna neurons | Antenna neurons | Ant | Ventral neurons, contact otolith foot and oaccs, looped axons, large terminals, invaginating terminal, many polyad synapses | [34]; [13]; [39] ;[6] | Glutamate | Anti (contacts both oaccs) and Ant2 (contacts only oacc2) | 2 | Ant1 (10), Ant2 (63) |  |

| otolith-associated ciliated cells | oaccs | Ventral cells, contact otolith with modified cilia. Contact antenna cells. No neurites. | [6] | oacc1 and oacc 2 | 2 | oaccl, oacc2 |  |

||

| Otolith | Statocyst | Ot | Ventral cell, foot and large single pigment granule in neural canal, proposed gravity receptor | [36]; [31] | Glutamate | - | 1 | Otolith |  |

| Ocellus pigment | Ocellus pigment cup | Oc | Right cell, contains many pigment granules, receives outer segments of photoreceptors, ciliated | [36] | - | 1 | Ocellus |  |

|

| Coronet cells | Cor | Left side cells, each has single cilium modified to bulbous protrusion, each has short axon to left side along basement membrane, dense core vesicle synapses | [31]; [37]; [29]; [34]; [35]; [39] ;[6] | Dopamine | synaptic contacts: basal lamina only, neurons and basal lamina | 16 | Corl-Corl6 |  |

|

| anaxonal arborizing neurons | aalN | posterior BV neurons with large expanded branched terminal adjacent to their cell bodies | [6] | pr-ant-aalN (102, 115), ant-aalN (95) | 3 | 95, 102, 115 |  |

||

| bipolar brain vesicle interneurons | bipolar interneurons | BPIN | bipolar BV intrinsic interneurons | [6] | pr-BPIN and pr-ant-BPIN | 2 | 90(pr-ant), 92(pr) |  |

|

| coronet associated ciliated brain vesicle interneurons | cor-ass BVIN | Ciliated BV intrinsic interneurons, cilia project to contact coronet bulbous protrusions, cells on left dorsal side | [35]; [6] | Varied sensory input, pr, ant, pr-ant, cor | 14 [15] | 1 (PNIN), 2(PNIN), 15, 23, 38(ant),55,59, 60(pr-ant), 62(cor),65 (PNIN) 68(pr-ant-cor), 70(pr-ant), 73(ant), 78(pr), 79(ant) |  |

||

| ciliated brain vesicle interneurons | BV intrinsic interneurons | BVIN | Ciliated neurons, dorsal left, fine axons | [35] ;[6] | Varied sensory input, pr, ant, pr-ant, cor | 19 | 3, 13, 17, 18, 21, 22, 24, 20, 33, 41, 42, 43, 48, 50, 61, 65, 85, 88, 92 |  |

|

| brain vesicle interneurons | BV intrinsic interneurons | BVIN | Cell bodies anterior to series | [12] ;[6] | 2 | ukn, ukn2 | |||

| brain vesicle photoreceptor interneurons | brain vesicle interneurons | prIN | Photoreceptor input (ciliated except those in bold) | [6] | ciliated and non-ciliated, some receive additional sensory input | 2 [10] | 13, 16, 17, 22, 42, 50, 68, 70, 78, 138 |  |

|

| brain vesicle antenna interneurons | brain vesicle interneurons | antIN | Antenna input (ciliated, Ant input only indicated by *) | [6] | some receive additional sensory input | [10] | 16, 24*, 33*, 38, 60, 68, 70, 73*, 79, 138 |  |

|

| anterior terminating rostral trunk epidermal neurons | RTENs I II III | pna/RTENs | anterior mechanosensory peripheral neuron (rostral trunk epidermal neuron) extending axon into the CNS BV | [41]; [42]; [43]; [44]; [45]; [39]; [23]; [46]; [14]; [22] | Glutamate | Left and Right | 6 | pnsl(L), pns2(L), pns5(R), pns6(R), pns9(R), pns13(L) |  |

| posterior brain vesicle terminating rostral trunk epidermal neurons | RTENS I II III | pnb/RTENs | anterior mechanosensory peripheral neuron (rostral trunk epidermal neuron ) extending axon into the CNS BV | [41]; [42]; [43]; [44]; [45]; [39]; [23]; [46]; [14]; [22] | Glutamate | Left and Right | 6 | pns3(L), pns4(L), pns7(R), pns11(R), pns12(L) | |

| Papillar neurons | palp neurons | Pap | Anterior neurons of palps | [41]; [44]; [39]; [45]; [23]; [46] | GABA, Glutamate | ||||

| peripheral interneurons | PNIN | BV intrinsic neuron, postsynaptic to RTENs, cilia do not enter | [22] | GABA | primary, secondary, ciliated, non ciliated | 5 [10] | 4, 6, 20, 25, 29, 30, 61, 65, 85, 88 |  |

|

| posterior brain vesicle peripheral interneurons | PBV PNIN | BV intrinsic neuron, cell body in posterior BV, postsynaptic to RTENs | [22] | - | 4 | 160, 162, 163, 164 |  |

||

| photoreceptor relay neurons | large ventroposterior interneurons | prRN | BV neurons, receive photoreceptor input, axons to MG, terminate in MG | [6] | GABA, Glutamate, Acetylcholine? | pr exclusive, some antenna input; MGL, MGL/R* | 6 | 80, 86*, 96*, 100*, 121, 126* | |

| photoreceptor-ascending motor ganglion neuron relay neurons | photoreceptor-peripheral relay neurons | pr-AMG RN/pr-PN RN | BV neurons, receive photoreceptor, AMG, and BTN input, exclusive postsynaptic RN partners of PR II, axons to MG, terminate in MG, branched terminals | [6], [22], [47] | GABA, Glutamate, Acetylcholine? | to only right side MG, to bilateral MG | 8 | 74, 94, 108, 116, 124, 127, 140, 157 | |

| photoreceptor-bipolar tail neuron relay ns | photoreceptor-peripheral neuron relay neurons | pr-BTN RN/pr-PN RN | BV neurons, eceptor and Bipolar tail neuron input, axons to MG, terminate in MG | [6], [22] , [47] | GABA, Glutamate, Acetylcholine? | - | 2 | 123, 130 | |

| photoreceptor-coronet relay neurons | multimodal relay neurons | pr-cor RN | BV neurons, receive photoreceptor and coronet input, axons to MG, terminate in MG | [6] | GABA, Glutamate, Acetylcholine? | Presynaptic to MNL2–4s, not presynaptic to MNs | 3 | 105, 112, 119 | |

| antenna 1 relay neurons | antenna relay neurons | anti RN/antRN | BV neurons, receive antennal input, axons to MG, terminate in MG | [6] | GABA, Glutamate, Acetylcholine? | Presynaptic to right MG, presynaptic to left and right MG | 3 | 147, 152, 161 | |

| antenna 2 relay neurons | antenna relay neurons | ant2 RN/antRN | BV neurons, receive antenna2 input, axons to MG, terminate in MG (left and right) | [6] | GABA, Glutamate, Acetylcholine? | 3 | 135, 153, 159 | ||

| antenna 1/2 relay neurons | antenna relay neurons | ant1/2 RN/antRN | BV neurons, receive antenna1 and antenna2 input, axons to MG, terminate in MG | [6] | GABA, Glutamate, Acetylcholine? | Ant-cor, ant-pr*, ant | 5 | 120, 134*, 142, 152* | |

| antenna-coronet relay neurons | antenna relay neuron | ant-cor RN/antRN | BV neuron, receives antenna 1 and 2 input and coronet input, axon terminates in MG | [6] | GABA, Glutamate, Acetylcholine? | - | [1] | 120 | |

| secondary relay neurons | non-sensory relay neurons | non-sensory RN/2° RN | BV neurons, not postsynaptic to sensory neurons, axons to MG, terminate in MG | [6] | GABA, Glutamate, Acetylcholine? | - | 5 | 93 (two single section Ant2 synapses), 103 (postsynaptic? To ATENa and presynaptic to prs), 106, 122 (postsynaptic to AMG7), 125 | |

| peripheral relay neuron | PNRN | BV neuron, postsynaptic to PNINs, PBV PNINs, BTNs, AMGs, pr-AMG, and presynaptic to Em1, terminates in MG | [6], [22] | - | 1 | 131 |  |

||

| eminens cells | peripheral relay neurons | Em | BV neurons, large, thick axon, receive input from pns neurons and their interneurons, terminate in rostral | [34] [44] [48] [49] [6], [22] [47] | GABA | Eminens1 and Eminens2 | 2 | Em1(109), Em2(99) | |

| neck neurons | NeckN | paired neck neurons, short axons, venral, just anterior to MG | [6] | NeckNL and NeckNR | 2 | 165, 166 |  |

||

| ascending motor ganglion peripheral interneurons | contrapelo cells, dorsal neurons, No. 4, 5, 6, 7, dorsal bipolar and multipolar neurons | AMG | Dorsal MG neurons, extend axons ventrally to MG then these turn and ascend to BV, interneurons of ATENp neurons | [34] ; [39] ; [6]; [22] , [47] | GABA, Acetylcholine | Left, Right, Bilateral, multipolar to pns | 7 | AMG1−7 |  |

| descending decussating neurons | descending decussating neuron | ddN | Anteriormost paired MG neurons, axons decussate, terminate in CNC, postsynaptic to PNS interneurons | [39] ; [50] ; [6]; [47] | Acetylcholine | Left and Right | 2 | ddNL (neuron1) and ddNR (count37) | |

| motor ganglion deseending interneuron pair 1 | Motor Ganglion paired deseending interneuron | MGIN1 | Paired ventral MG neurons, deseending ipsilateral axons that are not presynaptic to muscle, terminate in anterior caudal nerve cord | [34] ; [51] ; [39] ; [50] ; [6]; [47] | Acetylcholine | Left and Right | 2 | MGIN 1L, MGIN 1R | |

| motor ganglion descending interneuron pair 2 | Motor Ganglion paired descending interneuron | MGIN 2 | Second in series of paired ipsilateral MG interneurons, extend deep into caudal nerve cord | [34] ; [51] ; [39] ; [50] ; [6]; [47] | Acetylcholine | Left and Right | 2 | MGIN 2L, MGIN 2R | |

| motor ganglion descending interneuron pair 3 | Motor Ganglion paired descending interneuron | MGIN 3 | Most dorsal cell body of MG ipsilateral interneurons, terminates in posterior MG | [34] ; [51] ; [39] ; [50] ; [6]; [47] | Acetylcholine | Left and Right | 2 | MGIN 3L, MGIN 3R | |

| motor neuron pair 1 | motor neuron 1L (left) and 1R (right); motoneuron 1; primary motor neurons | MN1 | Paired ventral MG neurons, descending axons, frondose endplates presynaptic to dorsal and medial muscle, terminate in anterior CNC | [34] ; [51] ; [39] ; [50] ; [6]; [47] | Acetylcholine | Left and Right | 2 | MN1L, MN1R | |

| motor neuron pair 2 | motor neuron 2L (left) and 2R (right); motoneuron 2 | MN2 | Paired ventral MG neurons, descending axons with expansions along length like balls on string, presynaptic to muscle dorsal muscle, terminate deep in CNC | [34]; [51]; [39]; [50]; [6]; [47] | Acetylcholine | Left and Right | 2 | MN2L, MN2R | |

| motor neuron pair 3 | motor neuron 3L (left) and 3R (right); motoneuron 3 | MN3 | Paired ventral MG neurons, most dorsal of MNs, descending axons extend laterally then opposite dorsal muscle, presynaptic to muscle dorsal muscle, terminate in posterior MG/anterior CNC | [34]; [51]; [39]; [50]; [6]; [47] | Acetylcholine | Left and Right | 2 | MN3L, MN3R | |

| motor neuron pair 4 | motor neuron 4L (left) and 3R (right); motoneuron 4 | MN4 | Paired posterior MG/trunk tail border neurons, descending axons, presynaptic to dorsal muscle, terminate in posterior MG/anterior CNC | [51]; [39]; [6]; [47] | Acetylcholine | Left and Right | 2 | MN4L, MN4R | |

| motor neuron pair 5 | motor neuro n 5L (left) and 5R (right); motoneuron 5 | MN5 | Paired posterior MG/trunk tail border neurons, short descending axons, presynaptic to dorsal muscle , terminate in anterior CNC | [51]; [39]; [6]; [47] | Acetylcholine | Left and Right | 2 | MN5L, MN5R | |

| posterior motor ganglion interneurons | posterior MG interneurons | PMGIN | Posterior MG/trunk tail border neurons, unpaired, right side only, descending ipsilateral, mid-dorsal location | [6] | GABA | One longer with more synapses (1), one shorter with fewer synapses (2) | 2 | PMGN1 (tail8), PMGN2 (tail15) | |

| ascending contralateral inhibitory neurons | Ascending commissural inhibitory neurons | ACIN | Posterior MG/trunk tail border neurons, ascending and decussating | [52]; [51]; [53]; [6]; [47] | Glycine | left and right, 1 and 2 | 3 | ACIN1L (109*) , ACIN2L (tail7), ACIN2R (tail10) |  |

| midtail motor neurons | midtail neurons, planate cells | MTN | CNC paired neurons, short axons descend along muscle | [34]; [51]; [39]; [6]; | Acetylcholine | 1,2,4, 7, | 6 | MTN1, 2,3,4,5,6 | |

| bipolar tail neurons | bipolar tail neuron, tail neurons | BTN | Neurons between epidermis and CNS in the tail, extend axons bilaterally into the CNS, extend along length of animal up to BV | [34]; [44]; [51]; [39]; [10]; [6]; [22]; [47] | GABA, Acetylcholine | 2 left, 2 right; 1 bifid collateral axon 3 single axon | 4 | BTN1 (c2, Plan1) , BTN2 (n4, Plan2) , BTN3 (q3, Plan3) , BTN4 (x4/x6, Plan4) | |

| anterior apical trunk epidermal neurons | aATEN | Ciliated epidermal neurons dorsal to sensory neurons of CNS, short axons toward the epidermis opposite the CNS, terminate within epidermis, synapses onto basal lamina across from PNINs and Emine ns | [41]; [43]; [44]; [45]; [39]; [23]; [46]; [22]; [47] | Glutamate, GnRH | 4 | ATEN1-4 |  |

||

| posterior apical trunk epidermal neurons | pATEN | Ciliated epidermal neurons dorsal to posterior BV (relay neurons), short axons along epidermis opposite the CNS to the caudal nerve cord, cross basal lamina to contact dorsal CNS AMG neurons, extend back into epidermis in tail and synapse with ascending axons from DCENs | [41] ;[42]; [43]; [44];[45]; [39]; [23]; [46]; [22]; [47] | Glutamate | 4 | pna, pnb, pnc, pnf | |||

| dorsal caudal epidermal neurons | DCEN | Pairs of epidermal neurons with cilia to dorsal fin, axons along epidermis (PNS) opposite the CNS, overlap axon with next set of cell bodies | [41]; [42]; [43]; [44]; [45]; [39]; [23]; [46]; [22] | Glutamate | pnh, pnu, pnx, pnz |  |

|||

| ventral caudal epidermal neurons | VCEN | Pairs of epidermal neurons with cilia to ventral fin, axons along epidermis (PNS) | [41]; [42]; [43]; [44]; [45]; [39]; [23]; [46]; [22] | Glutamate |

Comprehensively exposed in the EM database, the cellular diversity of the simple Ciona larval CNS (Figure 2) may in fact be no less than in the more heavily populated brains of vertebrates. The connectome reveals features of ascidian larval neurons that in some cases are also unusual or unanticipated. Thus, the neuron terminal, which can be both pre-and postsynaptic, is simple and mostly unbranched, an axon is sometimes lacking, and most neurons are ciliated. Cilia from 81 such cells do not actually project into the lumen of the neural canal, however [6]. Unusual features include: some neurons such as three arborizing cells in the brain vesicle that each branch immediately into terminals and lack connecting axons; the coronet cells that lack both true axons and terminals; and neurons with bifid axons with long collaterals [6]. Most synapses form upon postsynaptic neurons, but others form onto the basal lamina that enwraps the CNS. Like their vertebrate counterparts ependymal cells conversely lack both synapses and an axon and in these ways resemble glia, which otherwise lack clear counterparts in the larval CNS of Ciona; myelin is also lacking [14].

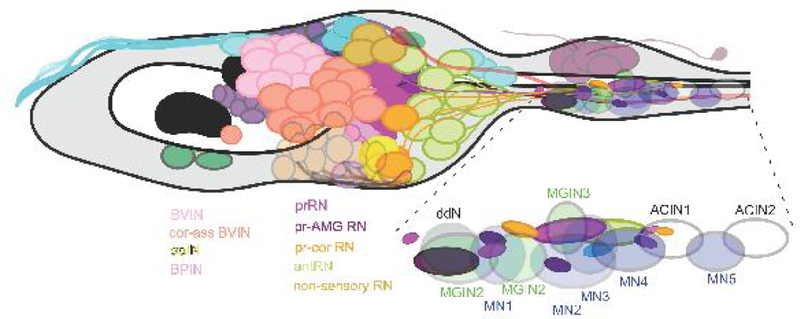

Figure 2.

A. Map of the sensory neurons and motor system of the larval nervous system of Ciona. Cell types named, labelled and colour-coded as in Table 1. After Ryan et al. [6].

B. As in A, but with the addition of interneurons in the brain vesicle to show their relative placement. These are shown enlarged in Figure 2 . Redrawn after Ryan et al. [6,22].

C. Dorsal view of 3D reconstruction of cell bodies illustrated in B, note BVINs are yellow instead of pink. After Ryan et al. [22]

Other features reflect the common ancestry of tunicates and chordates and are a more familiar read. Thus, photoreceptors in both groups are ciliary [15, and earlier literature cited therein], while coronet cells [6] are functionally enigmatic structural isomorphs of cells in the saccus vasculosus of the fish hypothalamus. Despite resembling saccus vasculosus neurons, ascidian coronet cells are likewise components of a morphologically homologous structure that is bilateral in vertebrates [16], but unilateral and unpaired in Ciona [6]. In vertebrates, the saccus vasculosus comprises coronet cells in addition to neurons contacting the cerebrospinal fluid. In Ciona newly reported ciliated coronet-associated neurons, having cilia that project into the neural canal toward the coronet cells’ bulbous protrusions, are likewise similar to cells in the fish saccus vasculosus. The coronet cells alone, or in combination with these associated neurons have a unique and robust transcriptional identity [17]. In both vertebrate and ascidian cases, it is these neurons rather than the coronet cells that give rise to an axon [18].

Few cells and synapses

The ascidian larval CNS has many types of neurons, each type with few representatives (Figure 1; Figure 2; Table 1).

For Ciona’s entire larval nervous system old reports provide the following tally of cell populations. A single larva comprises about 2,600 larval cells [19] that include 40 notochord and 36 muscle cells but are otherwise mostly epidermal cells. These numbers may be essentially fixed, or eutelic, the product of fixed cell lineage in the embryo [20,21]. Cell numbers for the CNS come from data for three sibling larvae, which had 335±4 CnS cells in total [12]. Of these, a single unrelated larva’s CNS contained 177 neurons constituting ≥25 types with 72 subtypes, most identified uniquely, including 5 pairs of motor neurons [6] (Figure 2; Figure 3). Together these formed 6618 synapses, including 922 (14%) dyads - at which a single synaptic site incorporates two postsynaptic dendrites opposite a single presynaptic release site, and 1772 neuromuscular synapses [6]. In addition 1206 close membrane appositions were interpreted as gap junctions. Both synapses and presumed gap junctions can occur between neurons of the same cell type [6]. All data are from Ryan et al. [6]. The remaining cells are the non-neuronal ciliated ependymal cells that line, and project cilia into, the lumen of the neural canal.

Figure 3.

Enlarged view of the brain vesicle interneurons named and colour-coded as in Table 1. Based on an enlarged view of Figure 2B.

Inset: Enlargement of the motor ganglion showing the locations of terminals from relay neuron types, relative to the locations of the motor ganglion somata.

Neurons are sparsely connected: on average each has 14 partners, and forms on average ~49 synapses of varied sizes, having a mean cumulative depth of 4.68μm [6], that are each thus validated because they extend through several serial ultrathin sections. Neuromuscular junctions of the five pairs of motor neurons are larger than synapses between neurons; each pair forms a specific shape of endplate.

Peripheral neurons

The cells of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) are fairly well documented in older literature, and their inputs to the CNS recently identified and reviewed [11,22]. PNS input arises from scattered groups of epidermal neurons (Figure 2), 54 in total [23], of which 32 are reconstructed in serial EM [22]. Substrate preference and induction of early metamorphosis in the presence of external chemical and physical stimuli suggest that PNS neurons, those that bear 9+2 cilia, can sense both chemical and mechanical cues [23,24]. The most anterior papillar neurons are designated touch chemoreceptors, although their mechanosensory capacity is untested while, among other classes of PNS neurons, all epidermal neurons are proposed mechanoreceptors, but their chemoreceptive capacity has not been evaluated [11,22]. The papillar neurons also group separately from remaining epidermal neurons in transcriptome analyses [17].

Neuronal identities: Many cell types

Despite their small number, CNS cells comprise many types, known almost entirely on morphological grounds (Table 1). Many remain anonymous among brain vesicle interneurons (Figure 2) and are classified according to their connections. Restricting the designation of these to neurons having a discriminable combination of anatomical characters, each type thus has few cells, many classes in fact having a sole representative (Figure 3). Additional criteria of neurotransmitter phenotype and electrical excitability are mostly not known, but may be expected to arbitrate additional cell types. Indeed, transcriptome analysis separates neurons with gene expression indicating a cholinergic phenotype from those indicating a GABAergic phenotype [17], but does not separate these neurons further; other neurotransmitters, and any further subcategories of neurons sharing neurotransmitter phenotype [25] await further transcriptome analyses. One value of a connectome is to enable a complete accounting of all cell types, including types that might be known in vertebrate brains but not from their numbers of representatives, or simply overlooked among the forest of others. For example, most CNS neurons -- 120 of 177 -- are ciliated, and all remaining cells appear to contain basal bodies, even if they may lack canonical ciliary extensions from the soma.

Neurons of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) are distributed in the epidermis and have relay neurons in the CNS [22]. Overall, many classes of sensory neurons have been identified, chiefly from their location over the epidermal field, and ciliary type.

Synapses

Ascidian larval neurons branch sparsely, and in most cases are axons with simple terminals arising from somata that mostly lack dendrites and deny easy morphological classification (Figure 4; Table 1). Given that the number and arborization of a neuron’s dendrites have been interpreted as a function of the number and range of their synaptic inputs [26], the lack of dendrites in Ciona neurons can be interpreted to reflect the paucity of synaptic inputs. But this may not be so. Thus, although many of the larval neurons in Ciona with dendrites fall among those with the greatest overall number of synaptic inputs, others lacking dendrites fall among this population as well. In addition, in Ciona neurons many synaptic involvements fail to segregate to different regions of the cell surface, so that although some input neurons synapse upon the soma, and output neurons occupy the terminal, dendrites are lacking, most synapses are axo-axonic, forming en passant between their axon and the axons of neighbours, or between terminal regions [6]. These features are shared with the neurons of C. elegans, and given the phylogenetic gulf between the two species such similarities may reflect more the compactness and similar neuron numbers of the nervous systems in the two species than deeper-seated similarities

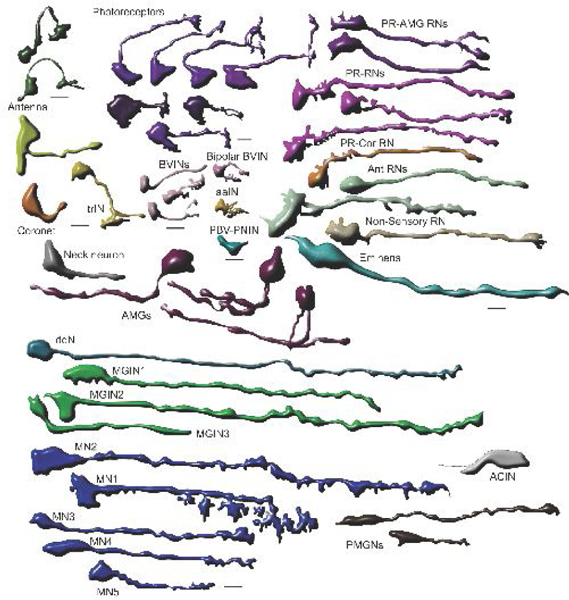

Figure 4.

All reconstructed CNS larval neurons in Ciona, grouped by morphological type, showing representatives of different cell types/morphologies. Cells are arranged for greatest spacing efficiency, without reference to their placement in the larva. Most are presented from a left lateral view.

The comprehensive matrix of synaptic contacts between identified neurons is a rich and mostly decisive resource for the identification and characterization of neuron types. Most of these synapses are simple and conventional, with a cumulus of presynaptic vesicles, either a sole tight cluster of small electron-lucent vesicles 30–60 nm in diameter, or accompanied at some synapses by larger (70–110 nm) electron-lucent vesicles, or dense-core vesicles 70–90 nm or 100–110 nm in diameter. Some synapses, especially those of antennal neurons, are dyads, having two postsynaptic elements opposite a single presynaptic site. Different functional configurations include reciprocal and serial synapses and bidirectional synapses at which pre- and postsynaptic structures sit opposite each other in partner neurons, like those reported in mollusc and cnidarian nervous systems [27].

Criteria for differentiating cell types

Neurons are so classified on the bases of being presynaptic to another cell at chemical synapses. Additionally, most have axons, although some, such as coronet cells, lack obvious axons or terminals. Axons are sometimes bifid, with collaterals. The simplicity of larval neuron morphology in Ciona also limits its use as a tool to categorize neurons, however. Sensory neurons are identified by their sensory structures, but otherwise neurons in this system are classified by their connections. Even motor neurons are so classified solely by their synaptic contacts onto muscle and diverse endplate morphologies, and interneurons are subdivided based upon the inputs from sensory classes. Individual neuron differences within larger classes do have morphological or ultrastructural criteria, however: depth of terminals within the CNS, projection of axons (Figure 3), expansions near the axon-hillock, bifurcation, terminal shapes (Figure 4). Postsynaptic sites are concentrated more densely near the axon hillock of many relay neurons. As in any nervous system, many of these distinguishing neuronal features are related to the locations of soma, axons, or targets. For example, large ventral interneurons are unimaginatively named because they are large and ventral, and their shape reflects their ventral location relative to the relay neuropil to the motor ganglion.

Recently reported single-cell transcript analyses [17] provide the prospect to validate and augment these anatomical categories, but also impose their own uncertainties. At present, transcriptome analysis has separated broad classes of neurons, but have not elucidated further cell type classifications. Cells in clusters other than the one containing photoreceptors express visual cycle genes; epidermal cells and brain vesicle cells are clustered together, possibly soliciting further subdivision; while glutamate transport gene expression is difficult to ascertain because of a poorly annotated gene model.

Cell types each have few constituent neurons

Most neuron classes have few constituents, many containing just a single cell (Figure 4); exceptions are photoreceptors, coronet cells, and local interneurons, which each comprise between 15 and 25 neurons. These are reported from multiple individuals for photoreceptors [6,12,13, 28] and coronet cells [6,12,29,17]. Even among these, there may be subtypes however, such as those defined by the rows or outer segment arrangement in type I photoreceptors [5], or by their connections [30]. Insofar as most subtypes are defined by their connections, a single connectome can predict cell types, but the number of constituent types remains inconclusive until resolved in multiple individuals.

Network analysis endorses morphological cell types

Connectivity network analysis identifies communities or clusters that separate the identified cell types, providing computational support for their identities. Thus, even with subtle differences between individual neurons’ contacts and networks, computational models group, for example, photoreceptor relay neurons together, and separate these from photoreceptor-AMG or photoreceptor-PN relay neurons [6,22]. This is not surprising given that many of these classes were determined based on their connections. Some also exhibit morphological characters, such as multipolar AMG neurons, and bifurcated terminals in many of the pr-AMG neurons, or positional clustering of somata or axons. In these cases, the questions of whether the cell lineage of these populations is perfectly fixed, and whether form determines function or function determines form is as yet unresolved.

Conclusions and prospects

The current analyses of the nervous system of the ascidian tadpole larva not only report the connectome of identified cell types, but yield a Pandora’s box of further questions. High on the list of these is whether the cell types of a second larva would be identical to those now known from the first. A high second priority would be to identify the neurotransmitter system, cell by cell, and the neurotransmitter receptors expressed by postsynaptic neurons identified by the connectome, for which application of single-cell transcriptomic methods are now underway [17]. Technological and methodological advances will doubtless require further revisions in the lineages and cell types.

A cost of having a comprehensive connectome is that we can no longer cherry-pick cell homologies between Ciona and vertebrate neurons, without reference to many other types that until recently had been anonymous, nor can we simply assume that ascidian neurons are just simple versions of vertebrate neurons, when many cell types are demonstrably complex and their components unexplained, and yet others simply enigmatic. At best we see that many tunicate neurons have chordate features, some previously identified, but others with basal features that help to identify those in the nervous systems of forms ancestral to both urochordate and chordate brains.

Acknowledgements

The authors’ original work covered in this review was supported by NSERC Discovery Grant A-0000065 (Ottawa) and by a subcontract award from NINDS (1RO1NS103774) to Dr. W.C. Smith (PI, University of California Santa Barbara). We also acknowledge with thanks the technical assistance of Mr. Zhiyuan Lu and Mss. Jane Anne Horne and Carlie Langille.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors of this work declares any conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

For submission to Current Opinion in Neurobiology

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as: * of special interest ** of outstanding interest

- 1.White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S: The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Phil Trans Roy Soc Lond Ser B 1986, 314:1–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichtman JW and Sanes JR Ome sweet ome: what can the genome tell us about the connectome? Curr Opin Neurobiol 2008, 18, 346–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durbin RM: Studies on the development and organisation of the nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans. PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarrell TA, Wang Y, Bloniarz AE, Brittin CA, Xu M, Thomson JN, Albertson DG, Hall DH Emmons SW: The connectome of a decision-making neural network. Science 2012, 337:437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan K: The Connectome of the Larval Brain of Ciona intestinalis (L.). PhD Thesis, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan K, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA: The CNS connectome of a tadpole larva of Ciona intestinalis highlights sidedness in the brain of a chordate sibling. eLife 2016, 5: e16962.** This is the first report of all the neurons of the CNS from a comprehensive EM connectome study that identifies new cell types, their identities, and connections, and confirms previous reports for known neurons.

- 7.Satoh N, Rokhsar D, Nishikawa T: Chordate evolution and the three-phylum system. Proc Biol Sci 2014. 281(1794):20141729. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1729.* This report highlights an important shift in our understanding of the division of deuterostomes into two clades, of which ascidians belong to the chordate clade, and details the evolutionary placement of Ciona and other ascidians as a sister group of all vertebrates.

- 8.Satoh N: Developmental Biology of Ascidians. Cambridge University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hotta K, Mitsuhara K, Takahashi H, Inaba K, Oka K, Gojobori T, Ikeo K: A web-based interactive developmental table for the ascidian Ciona intestinalis, including 3D real-image embryo reconstructions: I. From fertilized egg to hatching larva. Dev Dyn 2007. 236:1790–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.*Stolfi A, Ryan K, Meinertzhagen IA, Christiaen L: Migratory neuronal progenitors arise from the neural plate borders in tunicates. Nature 2015, 527:371–374. doi: 10.1038/nature15758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson C: The central nervous system of ascidian larvae. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol (2016), 5:538–561. doi: 10.1002/wdev.239.**A comprehensive recent resource reviewing the literature on the larval nervous system of various ascidian larvae that was made before the release of the Ciona connectome.

- 12.Nicol D, Meinertzhagen IA. Cell counts and maps in the larval central nervous system of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis (L.). J Comp Neurol 1991, 309:415–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horie T, Sakurai D, Ohtsuki H, Terakita A, Shichida Y, Usukura J, Kusakabe T, Tsuda M: Pigmented and nonpigmented ocelli in the brain vesicle of the ascidian larva. J Comp Neurol, 2008, 509:88–102. doi: 10.1002/cne.21733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan K, Meinertzhagen IA: “Urochordate Nervous Systems” In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Neuroscience (ed. Sherman SM). New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. Online: doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264086.013.206.** This recent review details our current state of knowledge of larval and adult nervous systems in urochordates, including some discussion of the cell types in different species and at different stages in the life cycle.

- 15.Lamb T: Evolution of phototransduction, vertebrate photoreceptors and retina. Progr Retina & Eye Res, 2013. 36:52–119. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smeets W, Nieuwenhuys R, Roberts BL: The Central Nervous System of Cartilaginous Fishes: Structure and Functional Correlations. Berlin Heidelberg and New York: Springer-Verlag, 1983. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68923-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma S, Wang W, Stolfi A. Single-cell transcriptome profiling of the Ciona larval brain. BioRxiv May 09, 2018.** This report provides a first look at single cell transcriptomics in the nervous system of Ciona larvae. It identifies defining transcripts of specific cell types, and classifies nervous system cells into broad groups based on their shared gene expression.

- 18.Rodríguez-Moldes MI, Anadón R: Ultrastructural study of the evolution of globules in coronet cells of the saccus vasculosus of an elasmobranch (Scyliorhinus canicula L.), with some observations on cerebrospinal fluid-contacting neurons. Acta Zool (Stockh) 1988, 69:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satoh N: Cell fate determination in the ascidian embryo In Cell-lineage and Fate Determination, ed. Moody SA, pp. 59–74. London: Academic Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemaire P: Unfolding a chordate developmental program, one cell at a time: invariant cell lineages, short-range inductions and evolutionary plasticity in ascidians. Dev Biol 2009, 332:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasakura Y, Mita K, Ogura Y, Horie T: Ascidians as excellent chordate models for studying the development of the nervous system during embryogenesis and metamorphosis. Dev Growth Differ 2012, 54:420–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2012.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan K, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA: The peripheral nervous system of the ascidian tadpole larva: Types of neurons and their synaptic networks. J Comp Neurol 2018, 526:583–608. 10.1002/cne.24353.* A detailed account of the peripheral neurons in larval Ciona by cell type, describing for the first time their connections, identifying novel cell types involved in PNS pathways, and further revealing identified cells at the ultrastructural level.

- 23.Terakubo HQ, Nakajima Y, Sasakura Y, Horie T, Konno A, Takahashi H, Inaba K, Hotta K, Oka K: Network structure of projections extending from peripheral neurons in the tunic of ascidian larva. Dev Dyn 2010, 239:2278–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caicci F, Zaniolo G, Burighel P, Degasperi V, Gasparini F, Manni L: Differentiation of papillae and rostral sensory neurons in the larva of the ascidian Botryllus schlossen (Tunicata). J Comp Neurol 2010, 518:547–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brozovic M, Martin C, Dantec C, Dauga D, Mendez M, Simion P, Percher M, Laporte B, Scornavacca C, Di Gregorio A, Fujiwara S, Gineste M, Lowe EK, Piette J, Racioppi C, Ristoratore F, Sasakura Y, Takatori N, Brown TC, Delsuc F, Douzery E, Gissi C, McDougall A, Nishida H, Sawada H, Swalla BJ, Yasuo H, Lemaire P: ANISEED 2015: a digital framework for the comparative developmental biology of ascidians. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44(D1):D808–818. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv966.** This is the most comprehensive current database on ascidian development, gene and protein expression.

- 26.Purves D, Hume RI: The relation of postsynaptic geometry to the number of presynaptic axons that innervate autonomic ganglion cells. J Neurosci 1981, 1:441–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meinertzhagen IA: Morphology of invertebrate neurons and synapses In: Handbook of Invertebrate Neurobiology (ed. Byrne JH). Oxford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oonuma K, Tanaka M, Nishitsuji K, Kato Y, Shimai K, Kusakabe TG: (2016). Revised lineage of larval photoreceptor cells in Ciona reveals archetypal collaboration between neural tube and neural crest in sensory organ formation. Dev Biol 420:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.* Report detailing an important revision of the late lineage of photoreceptor neurons, illustrating how established neuronal lineages have been brought into question by advanced techniques.

- 29.Moret F, Christiaen L, Deyts C, Blin M, Joly JS, Vernier P: The dopamine-synthesizing cells in the swimming larva of the tunicate Ciona intestinalis are located only in the hypothalamus-related domain of the sensory vesicle. Europ J Neurosci 2005, 21:3043–3055. DOI: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salas P, Vinaithirthan V, Newman-Smith E, Kourakis MJ, Smith WC. Photoreceptor specialization and the visuomotor repertoire of the primitive chordate Ciona. J Exp Biol 2018, 221: pii: jeb177972. doi: 10.1242/jeb.177972.* This recent report identifies novel visual behaviours and uses connectomic information to relate these to photoreceptor cell types.

- 31.Dilly PN: The nerve fibres in the basement membrane and related structures in Saccoglossus horsti (Enteropneusta). Z Zellforsch. mikrosk Anat. 1969, 971: 69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kusakabe T, Kusakabe R, Kawakami I, Satou Y, Satoh N, Tsuda M: Ci-opsin1, a vertebrate-type opsin gene, expressed in the larval ocellus of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. FEBS letters 2001, 506: 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horie T, Orii H, Nakagawa M: Structure of ocellus photoreceptors in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis larva as revealed by an anti-arrestin antibody. J Neurobiol 2005, 653: 241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imai JH, Meinertzhagen IA: Neurons of the ascidian larval nervous system in Ciona intestinalis: I. Central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 2007, 5013: 316–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konno A, Kaizu M, Hotta K, Horie T, Sasakura Y, Ikeo K, Inaba K: Distribution and structural diversity of cilia in tadpole larvae of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Dev Biol 2010, 337: 42–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berrill NJ: The development and growth of Ciona. J Mar Biol Association of the United Kingdom 1947, 264: 616–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eakin RM, Kuda A: Ultrastructure of sensory receptors in ascidian tadpoles. Z. Zellforsch mikrosk Anat 1970, 1123: 287–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimeld SM, Purkiss AG, Dirks RPH, Bateman OA, Slingsby C, Lubsen NH: Urochordate βγ-crystallin and the evolutionary origin of the vertebrate eye lens. Curr Biol 2005, 15: 1684–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takamura K, Minamida N, Okabe S: Neural map of the larval central nervous system in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Zool Sci 2010, 272: 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dilly PN: Studies on the receptors in the cerebral vesicle of the ascidian tadpole, i. The otolith. J Cell Sci 1962, 363: 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takamura K: Nervous network in larvae of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Develop Genes Evol 1998, 2081: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Candiani S, Pennati R, Oliveri D, Locascio A, Branno M, Castagnola P, Pestarino M, De Bernardi F: Ci-POU-IV expression identifies PNS neurons in embryos and larvae of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Develop Genes Evol 2005, 215: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mazet F, Hutt JA, Milloz J, Millard J, Graham A, Shimeld SM: Molecular evidence from Ciona intestinalis for the evolutionary origin of vertebrate sensory placodes. Dev Biol 2005, 282: 494–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imai JH, Meinertzhagen IA. Neurons of the ascidian larval nervous system in Ciona intestinalis: II. Peripheral nervous system. J Comp Neurol 2007, 5013 (2007: 335–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horie T, Kusakabe T, Tsuda M: Glutamatergic networks in the Ciona intestinalis larva. J Comp Neurol 2008, 5082: 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yokoyama TD, Hotta K, Oka K: Comprehensive morphological analysis of individual peripheral neuron dendritic arbors in ascidian larvae using the photoconvertible protein kaede. Dev Dynam 2014, 24310: 1362–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryan K, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA: Circuit homology between decussating pathways in the Ciona larval CNS and the vertebrate startle-response pathway. Curr Biol 2017, 275: 721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zanetti L, Ristoratore F, Francone M, Piscopo S, Brown ER. Primary cultures of nervous system cells from the larva of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. J Neurosci Meth 2007, 165: 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zega G, Biggiogero M, Groppelli S, Candiani S, Oliveri D, Parodi M, Pestarino M, De Bernardi F, Pennati R: Developmental expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase and of γ-aminobutyric acid type B receptors in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. J Comp Neurol 2008, 506: 489–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stolfi A, Levine M: Neuronal subtype specification in the spinal cord of a protovertebrate. Develop 2011, 1385: 995–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horie T, Nakagawa M, Sasakura Y, Kusakabe TG, Tsuda M: Simple motor system of the ascidian larva: neuronal complex comprising putative cholinergic and GABAergic/glycinergic neurons. Zool Sci 2010, 27: 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horie T, Nakagawa M, Sasakura Y, Kusakabe TG: Cell type and function of neurons in the ascidian nervous system. Develop, Growth & Different 2009, 51: 207–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishitsuji K, Horie T, Ichinose A, Sasakura Y, Tasuo H, Kusakabe TG. Cell lineage and cis-regulation for a unique GABAergic/glycinergic neuron type in the larval nerve cord of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Develop, Growth & Different 2012, 54: 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]