Abstract

Purpose:

Breast masses in pediatric patients are often managed in a similarly to adult breast masses despite significant differences in pathology and natural history. Emerging evidence suggests that clinical observation is safe. The purpose of this study was to quantify the clinical appropriateness of the management of benign breast disease in pediatric patients.

Methods:

A multi-institutional retrospective cohort study was completed between 1995–2017. Patients were included if they had benign breast disease and were 19 years old or younger. A timeline of all interventions (ultrasound, biopsy, or excision) was generated to quantify the number of patients who were observed for at least 90 days, deemed appropriate care. To quantify inappropriate care, the number of interventions performed within 90 days, and the pathologic concordance to clinical decisions was determined by reviewing the radiology reports of all ultrasounds and pathology reports of all biopsies and excisions.

Results:

A total of 1,909 patients were analyzed. Mean age was 16.4 years old (± 2.1). The majority of masses were fibroadenomas (60.4%). Only half of patients (54.3%) were observed for 90 or more days. 81.1% of interventions were unnecessary, with pathology revealing masses that would be safe to observe. The positive predictive value (PPV) of clinical decisions made based on suspicious ultrasound findings was 16.2%, not different than a PPV of 21.9% (p<0.25) for decisions made on clinical suspicion alone.

Conclusion:

Despite literature supporting an observation period for pediatric breast masses, half of patients had an intervention within three months with one out of ten patients undergoing an invasive procedure within this time frame. Furthermore, 81.1% of invasive interventions were unnecessary based on final pathologic findings. A formal consensus clinical guideline for the management of pediatric benign breast disease including a standardized clinical observation period is needed to decrease unnecessary procedures in pediatric patients with breast masses.

Keywords: Pediatric, Benign, Breast, Observation, Appropriateness

1. Introduction

Breast masses affect approximately 3% of pediatric patients in the United States [1,2]. The most common breast mass seen in this population is a benign fibroadenoma, and regardless of histologic subtype, 10–40% of clinically detected breast masses in the pediatric population will resolve completely without intervention [3,4]. Despite this, pediatric patients are often subject to invasive interventions such as biopsies and excisions for the management of benign disease. Variation in provider management is likely due to a lack of consensus guidelines resulting in providers managing this disease similar to adults and thus performing invasive interventions too frequently.

Current literature suggests that a period of observation of at least one to four menstrual cycles [1,5] is safe and minimization of invasive procedures is appropriate in this patient cohort. In a recent publication by McLaughlin et al. [6] a detailed observation algorithm, created by the authors, suggested that asymptomatic patients with suspected benign disease can be safely observed without surgery [6]. If patients must undergo further workup, the use of ultrasound is well described in the literature, with safety and tolerance of image guided biopsy also supported [7,8]. Several other studies suggest that patients should only undergo invasive procedures, biopsy or excision, if they present with a mass that is 4–5cm, have a personal history of cancer or chest radiation, or growth over a clinical observation period [1,7,9,10].

This retrospective multi-institutional study investigated the largest cohort to date of pediatric patients with benign breast disease to quantify the appropriateness of management with the hypothesis that many patients with benign breast disease do not undergo an observation period and instead undergo unnecessary invasive interventions.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

Analysis was performed on 1,909 patients with benign breast disease, aged 10 to 19 years old at the time of diagnosis. There were no patients less than 10 years old identified in the study cohort, thus this was made the lower age limit. Patients were identified through an algorithmic search of the Partners Healthcare Research Patient Data Registry (RPDR), an electronic medical record database of a not-for profit health care system that includes five large academic hospitals. The International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), ICD-10, and RPDR specific codes were used to extract patients with a diagnosis of benign breast disease (supplemental table 1). The interventions, ultrasound/biopsy/excision, were extracted using ICD-9, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), and RPDR specific codes (supplemental table 1).

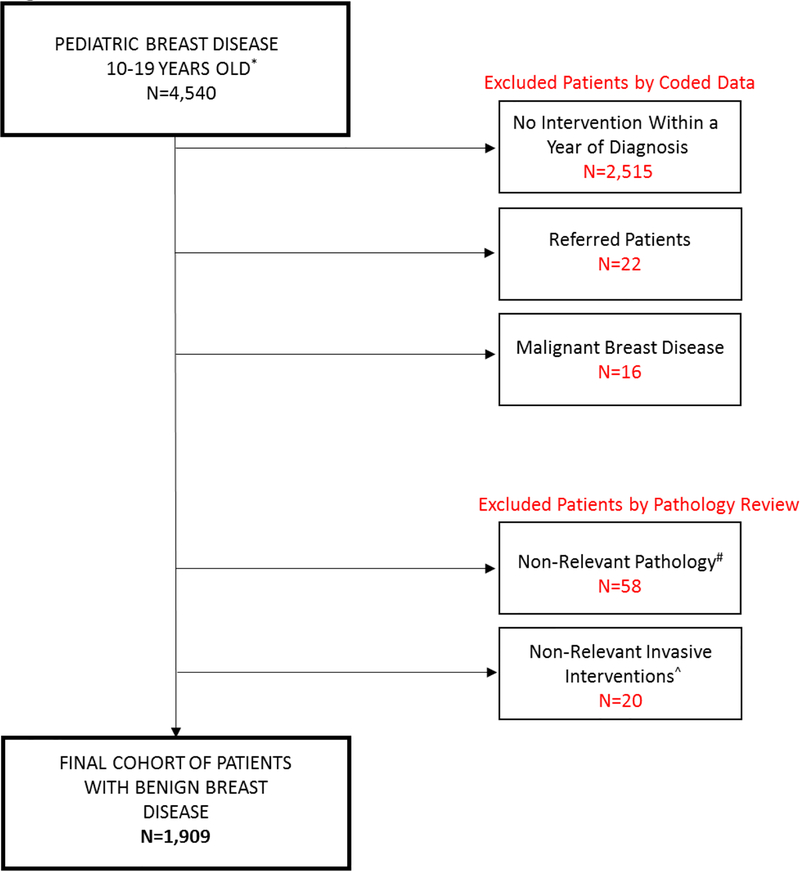

Exclusion criteria (Fig1) included patients that were referred as consults and did not have their work-up completed at the study institutions. Patients with cystic disease and those undergoing non-relevant procedures were also excluded. Non-relevant procedures included axilla excision, skin biopsy, skin excision, debridement without excision, and mammoplasty. Patients were also excluded if their initial intervention was greater than one year from the date of their breast mass diagnosis, as it is possible that the intervention was for a different breast mass. Finally, patients with malignant breast disease were also excluded from the study cohort (supplemental table 2 demonstrates codes used for identification of these patients prior to exclusion).

Fig1. Patient Cohort.

Flowchart depicting exclusion criteria and final number of patients included in study cohort.

*There were no patients identified under the age of 10 years old

# Cystic disease, pilomatricoma, supernumerary nipple

^ Axilla excision, skin biopsy, skin excision, debridement without excision, mammoplasty

2.2. Determining Timeline for All Interventions

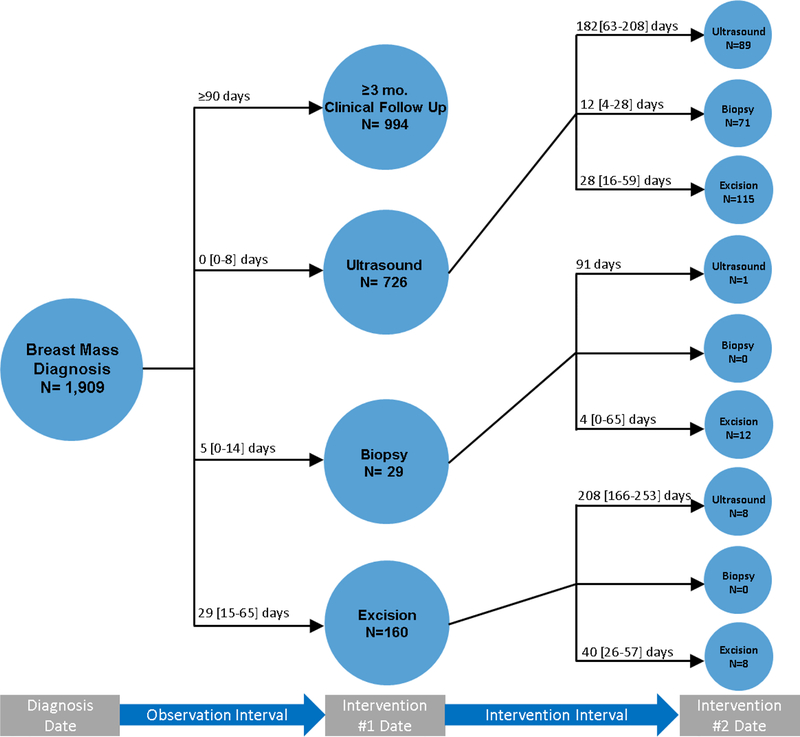

A clinical timeline (Fig2) was developed for all patients for the year following diagnosis of a benign breast mass. This included those patients who were followed clinically and those that underwent an ultrasound, biopsy, or excision. For patients that underwent an ultrasound, biopsy, or excision as their index intervention, subsequent interventions were also recorded if they occurred within one year from breast mass diagnosis. The observation period was determined by calculating the interval time period between breast mass diagnosis and the date of the index intervention (ultrasound, biopsy, excision). The intervals for any subsequent interventions were recorded by calculating the time between interventions.

Fig2. Timeline for All Interventions.

Timeline of all interventions performed within one year of breast mass diagnosis. The observation interval is defined as the interval between diagnosis and first intervention (ultrasound/biopsy/excision) or non-intervention (clinical follow up). Intervention interval is defined as the time between two interventions. Time displayed as medians [SD].

2.3. Determining Clinical Appropriateness and Pathologic Concordance

The first step in determining clinical appropriateness was to analyze all the initial interventions: clinical follow-up, ultrasound, biopsy, or excision. As described above, patients that underwent clinical follow-up for greater than or equal to three months were determined to have undergone clinically appropriate care. Patients that underwent an ultrasound within three months were determined to be possibly appropriate because these patients did not have a clinical observation period but had a non-invasive intervention. Finally, patients that underwent an invasive intervention (biopsy or excision) before completion of a three-month observation period were determined to have undergone inappropriate care.

To quantify the number of inappropriate invasive interventions performed in this patient cohort, pathologic concordance to the clinical decision was determined by reviewing the radiology reports of all ultrasounds and the pathology reports of invasive interventions (biopsies/excisions). First, the ultrasound reports were classified as suspicious or not suspicious. Suspicious ultrasounds included reports that were Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category 4 or higher, diagnosed pathology that would require intervention such as abscess, benign phyllodes, juvenile/cellular fibroadenoma, juvenile papillomatosis/intraductal papilloma, atypical lobular/ductal hyperplasia, or those that mentioned a suspicious abnormality with no further classification. Non-suspicious ultrasounds included reports that were BI-RADS category 3 or lower, those that did not reveal any abnormality, and those that diagnosed pathology that would not require intervention such as fibroadenoma, hamartoma, PASH, hemangioma, adenoma (tubular or lactating), benign breast tissue, nodular adenosis, focal sclerosis, lipoma, focal juvenile hypertrophy or fibrocystic changes. The authors did not take into consideration the final recommendation of the radiologist because many times an invasive intervention (biopsy or excision) was recommended with a non-suspicious diagnosis such as a report that read, “benign fibroadenoma, biopsy recommended”, with no further justification.

Patients were determined to have pathologic concordance if the results of the invasive intervention revealed pathology that was appropriate for biopsy or excision based on available literature [4,8,9,12–15]. This included the following diagnoses: benign phyllodes, juvenile/cellular fibroadenoma, juvenile papillomatosis/intraductal papilloma, atypical lobular/ductal hyperplasia, and abscess. Patients were determined to have pathologic discordance if the pathology revealed a diagnosis that did not require an intervention as listed previously.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A multi-institutional retrospective cohort study of 1,909 patients was completed. Analysis was performed using Stata Statistical Software version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Continuous variables were described as means with standard deviation. Categorical data were described as counts and percentages of total. Comparison of the positive predictive value of suspicious ultrasound and clinical suspicion was completed using a X2 test with p-value≤0.05 considered statistically significant.

This study was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board. Datasets generated and analyzed for the current study are not publicly available and contain PHI but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Tumor Demographics

A total of 1,909 female patients with breast masses were identified. 16 patients (0.8%) were found to have malignant disease and were excluded. Of the benign disease patients, mean age was 16.4 years old (SD ± 2.1). The majority of patients were white (50.2%), followed by Hispanic (22.5%), black (11.2%), other (4.6%) and Asian (2.4%) (Table 1). Analysis of tumor demographics revealed that 60.4% patients had fibroadenomas, 10.1% juvenile/cellular fibroadenomas, 9.0% hamartomas, 7.7% phyllodes, and 12.8% other (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Variables | Mean (SD) or N (% Total) N=1,909 |

|---|---|

| Age | 16.4 (±2.1) |

| Female | 1,909 (100%) |

| Race | |

| White | 958 (50.2%) |

| Hispanic | 429 (22.5%) |

| Black | 214 (11.2%) |

| Other* | 88 (4.6%) |

| Asian | 46 (2.4%) |

Other: American Indian, Hawaiian, and other code

Table 2.

Tumor Demographics

| Tumor Type | N (% of Total) N=366 |

|---|---|

| Fibroadenoma | 221 (60.4%) |

| Hamartoma | 37 (10.1%) |

| Juvenile/Cellular Fibroadenoma | 33 (9.0%) |

| Benign Phyllodes | 28 (7.7%) |

| Benign Breast Tissue | 14 (3.8%) |

| PASH | 11 (3.0%) |

| Adenoma (Tubular or Lactating) | 8 (2.2%) |

| Fibrocystic Changes | 2 (0.5%) |

| Duct ectasia | 2 (0.5%) |

| Juvenile Papillomatosis/Intraductal Papilloma |

4 (1.1%) |

| Abscess | 2 (0.5%) |

| Focal Juvenile Hypertrophy | 2 (0.5%) |

| Focal Sclerosis | 1 (0.3%) |

| Lipoma | 1 (0.3% |

3.2. Timeline of All Interventions (Fig2)

As seen in figure 2, the time to initial intervention was shortest for patients undergoing an ultrasound (0 [0–8] days) followed by biopsy (5 [0–14] days), and finally excision (29 [15–65] days). Of patients that underwent an ultrasound as their initial intervention, follow up biopsy and excisions occurred within a month (biopsy 12 [4–28] days, excision 28 [16–59] days), while follow up ultrasound occurred several months later (182 [63–208] days). Next, one patient underwent initial biopsy and had a follow up ultrasound at three months (91 days) while patients that underwent follow up excision did so most often within a week (4 [0–65] days). Finally, patients that underwent an excision as their index intervention had a follow up ultrasound approximately five to nine months later (208 [166–253] days) whereas repeat excisions were performed within two months (40 [26–57] days).

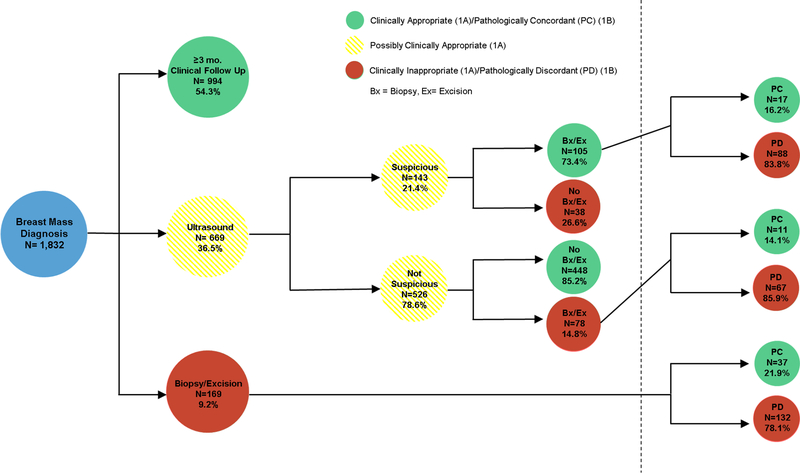

3.3. Clinical Decision Appropriateness and Pathologic Concordance with Clinical Decision (Fig3A/3B)

Fig3A/B. Clinical Decision Appropriateness (3A) and Pathologic Concordance with Clinical Decision (3B).

Fig3a depicts the clinical appropriateness of the initial clinical decision. Clinical follow up for greater than or equal to three months was deemed appropriate care. Ultrasound within three months was possibly clinically appropriate given that ultrasound could show suspicious disease warranting invasive intervention. Biopsy and excision within three months was deemed clinically inappropriate care. If patients underwent an intervention after suspicious ultrasound this was clinically appropriate (73.4%) but if they did not undergo an intervention after suspicious ultrasound this was inappropriate (26.6%). Similarly, if patients underwent an intervention after non-suspicious ultrasound this was inappropriate (14.8%), while patients who did not undergo an intervention after non-suspicious ultrasound were deemed appropriate care (85.2%). Fig3b shows the pathologic concordance with clinical decision making. Pathology that did not warrant intervention was pathologically discordant, while pathology that did warrant intervention was pathologically concordant with the clinical decision.

In assessment of the appropriateness of a provider’s index clinical decision, the data revealed that only half (54.3%) of patients were appropriately observed for greater than or equal to 90 days. About one third (36.5%) of patients underwent an ultrasound as their index intervention. Of these patients, one fifth (21.4%) were found to have a suspicious finding and 73.4% of this group appropriately underwent a follow up intervention of biopsy or excision. However, when assessing the pathologic concordance of these specimens, only 16.2% were found to have disease that warranted removal. Furthermore, even though the majority (78.6%) of patients who underwent an ultrasound had no suspicious findings, 14.8% still underwent a biopsy or excision and 85.9% of these specimens were pathologically discordant. Finally, one tenth (9.2%) of patients underwent a biopsy or excision as their index intervention, without any observation period. Of these patients, 132 (78.1%) had discordant pathology and underwent a biopsy or excision for disease that did not require intervention.

3.4. Pathologic Concordance with Clinical Expectation and Positive Predictive Value

Review of the pathology from all excisions and biopsies revealed that 81.1% of interventions were unnecessary, with pathology revealing masses that would be safe to observe (table 3a). The positive predictive value (PPV) of clinical decisions made based on suspicious ultrasound findings was 16.2%, not statistically different to a PPV of 21.9% (p<0.25) for decisions made on clinical suspicion alone (table 3b).

Table 3a.

Rate of Pathologic Concordance with Clinical Expectation

Includes: fibroadenoma, hamartoma, PASH, adenoma, benign breast tissue, focal sclerosis, lipoma, focal juvenile hypertrophy, fibrocystic changes

Includes: benign phyllodes, juvenile/cellular fibroadenoma, juvenile papillomatosis/intraductal papilloma, abscess

Table 3b.

Positive Predictive Value of Suspicious Ultrasound vs. Clinical Suspicion Alone as the Driver of Invasive Interventions (Excision/Biopsy)

| Pathologic Concordance (PPV) |

Pathologic Discordance |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound Suspicion | 17 (16.2%) | 88 (83.8%) | 0.25 |

| Clinical Suspicion Alone | 37 (21.9%) | 132 (78.1%) |

4. Discussion

Breast masses in children are most often benign and current literature supports the safety of clinical observation in this population at least as an initial management step. Adult breast surgeons, pediatricians and pediatric surgeons who see relatively few pediatric breast masses may continue to follow adult breast disease algorithms despite the very different pathophysiology of adolescent breast lesions. Many of the current management suggestions are found in radiology literature focusing on imaging and interventional procedures (core biopsy); these studies fail to provide clinical providers with clinical recommendations. The limited surgical literature also varies widely regarding management recommendations with most papers based on small, retrospective, single-institutional studies that lack the rigor needed to stimulate changes in provider management. We have collected and analyzed the largest number of adolescent patients with benign breast disease with regards to management and the need for intervention based upon patient pathology. We anticipate that this multi-institutional study on appropriateness of care will influence the algorithm for caring for adolescents with breast masses.

Despite growing evidence, pediatric patients continue to undergo interventions, both invasive and non-invasive, before completing a clinical observation interval for breast disease. In a recent publication, McLaughlin et al. [6] developed a clinical algorithm focusing on the safety of clinical observation. This algorithm, along with other studies, suggests that a reasonable observation period for patients with clinically benign breast disease is within the range of one to four menstrual cycles (or months) [1,5,15,16]. Just over half of our patient cohort (54.3%) completed an observation interval of at least 90 days with the remainder undergoing an intervention within a month (average intervention time of 11 days). As ultrasound was included in the intervention group for this study, we also compared the appropriateness of ultrasound, by assessing its concordance with final disease pathology.

If providers are compelled to intervene within 90 days of diagnosis, an ultrasound is often the first step considered given that it is non-invasive compared to excisions/biopsies and is supported in the current literature. Surprisingly, review of our data shows that the PPV of ultrasound was only 16.2%. This was not found to be statistically different from the PPV of clinical suspicion alone (21.9%, p=0.25) suggesting that the ultrasound was not better at predicting benign disease than clinical suspicion alone. Therefore, instead of pushing patients towards an intervention of any kind (ultrasound/biopsy/excision), providers should focus on clinical observation for the first 90 days. In this patient cohort, 99.2% of all masses were technically safe to observe for at least 90 days given that they were nearly all pathologically benign. The developing breast is prone to iatrogenic injury [8,9,11], and clinical observation can help mitigate this risk by decreasing unnecessary interventions.

It is understandable that some providers remain concerned that by observing a mass for several months, they may be delaying the diagnosis of malignant disease. Therefore, secondary to provider and/or patient/patient family anxiety, they are pushed to intervene before completing any observation period. Our findings do not suggest that this leads to findings of malignant disease. The indications for surgery have been suggested in several studies and the authors agree that pediatric patients should only undergo an invasive intervention if they present with a mass greater than five centimeters or shows rapid growth after a period of observation (> 20% in 6 months) [7,9]. The only exception to this standard should be patients with a personal history of cancer or chest radiation [1]. Although ultrasound has been used to reassure patients and care givers, our data would suggest that ultrasound and clinical suspicion alone have similar predictive values for disease warranting intervention. Thus, a period of clinical observation may be more useful than ultrasound in guiding decisions for biopsy/excision. If after a period of observation, there has been continued growth of the mass, referral of pediatric patients to undergo core biopsy [17] has been shown safe and well tolerated. Excision of pediatric breast masses should be reserved for those patients with rapidly growing masses or those with biopsy proven phyllodes, cellular fibroadenoma, papillomatosis/papilloma.

Data from this study and the recent publication from McLaughlin et al. [6] both support the clinical observation of pediatric patients with benign breast disease. However, referring providers must consider who is most appropriate to observe these masses. Providers should have a practice that at least in part focuses on pediatric breast disease and should collaborate closely with the both patients/patient families and community providers, to provide education regarding the benign pathology that is most often encountered in this patient population [13,18]. Anecdotally, adequate patient/patient family education, can greatly decrease the number of interventions patients undergo, with patients more often opting for repeated clinical breast exams instead of ultrasounds or biopsies/excisions. With a data supported clinical approach, adequate patient and referring provider education, the authors believe the number of inappropriate interventions will decrease.

Given the retrospective nature of this study, there are several limitations that must be considered. First, because of the large size of the patient cohort it was not feasible to perform an individual chart review on every patient to determine the indication for invasive intervention. Therefore, the authors are unable to determine how many patients underwent an invasive intervention for the appropriate indications based on size, growth, or history of cancer or radiation. Along similar lines, patients who underwent biopsy or excision as their first intervention could have been seen at an outside hospital and referred to our providers after a period of observation that was not documented in our system. Finally, there were several patients who had missing radiology and/or pathology reports thus there is missing data as demonstrated in figure 3 with a total sample size of 1,832 for this part of the analysis.

5. Conclusions

Despite literature supporting an observation period for pediatric breast masses, nearly half of patients in this large cohort of pediatric patients with benign breast disease had an intervention within three months, with nearly one tenth of patients subjected to an invasive procedure within the same time period. Furthermore, 81.1% of all invasive interventions were unnecessary at any time interval based on final pathologic findings. Providers must understand the nature of pediatric breast disease in order to feel comfortable safely observing pediatric breast masses for at least 90 days. Furthermore, it is important that providers understand that ultrasound was not superior to clinical suspicion alone in diagnosing disease that warranted invasive intervention. Overall, a formal consensus clinical guideline for the management of pediatric benign breast disease including a standardized clinical observation period and the use of biopsy over excision is needed to decrease unnecessary procedures in this vulnerable patient population.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

ML Westfal is financially supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (Award Number: T32 DK007754) and by the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery Marshall K. Bartlett Fellowship. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Westfal declares that she has no conflict of interest. Dr. Perez declares that he has no conflict of interest. Dr. Hung declares that she has no conflict of interest. Dr. Chang declares that he has no conflict of interest. Dr. Kelleher declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval:

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent:

This study did not involve contact with any humans and therefor informed consent was not required. Informed consent was waived with approval of the Massachusetts General Hospital IRB.

References

- 1.Knell J, Koning JL, Grabowski JE. Analysis of surgically excised breast masses in 119 pediatric patients. Pediatr Surg Int 2016;32(1):93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neinstein LS, Atkinson J, Diament M. Prevalence and longitudinal study of breast masses in adolescents. J Adolescent Health 1993;14(4):277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezer SS, Oguzkurt P, Ince E, Temiz A, Bolat FA, Hicsonmez A. Surgical Treatment of the Solid Breast Masses in Female Adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013;26(1):31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerrato F, Labow BI. Diagnosis and Management of Fibroadenomas in the Adolescent Breast. Semin Plast Surg 2013;27(1):23–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciftci AO, Tanyel FC, Buyukpamukcu N, Hicsonmez A. Female breast masses during childhood: a 25-year review. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1998;8(2):67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin CM, Gonzalez-Hernandez J, Bennett M, Piper HG. Pediatric breast masses: an argument for observation. J Surg Res 2018;228:247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West KW, Rescorla FJ, Scherer LR 3rd, Grosfeld JL. Diagnosis and Treatment of Symptomatic Breast Masses in the Pediatric Population. J Pediatr Surg 1995;30(2):182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valeur NS, Rahbar H, Chapman T. Ultrasound of pediatric breast masses: what to do with lumps and bumps. Pediatr Radiol 2015;45:1584–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, Saksena MA, Brachtel EF, Termeulen DC, Rafferty EA. How to approach breast lesions in children and adolescents. Eur J Radiol 2015;84(7):1350–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders LM, Sharma P, El Madany M, King AB, Goodman KS, Sanders AE. Clinical breast concerns in low-risk pediatric patients: practice review with proposed recommendations. Pediatr Radiol 2018;48(2):186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung EM, Cube R, Hall GJ, Gonzalez C, Stocker JT, Glassman LM. Breast Masses in Children and Adolescents: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. RadioGraphics 2009;29(3):907–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaneda HJ, Mack J, Kasales CJ, Schetter S. Pediatric and Adolescent Breast Masses: A Review of Pathophysiology, Imaging, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Am J Roentgenol 2013;200(2):W204–W212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amin AL, Purdy AC, Mattingly JD, Kong AL, Termuhlen PM. Benign Breast Disease. Surg Clin N Am 2013;93:299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsedfy H A clinical approach to benign breast lesions in female adolescents. Acta Biomed 2017;88(2):214–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonmez K, Turkyilmaz Z, Karabulut R, et al. Surgical Breast Lesions in Adolescent Patients and a Review of the Literature. Acta Chirurgica Belgica. 2006;106(4):400–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diehl T, Kaplan DW. Breast Masses in Adolescent Females. J Adolesc Health Care 1985;6(5):353–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duflos C, Plu-Bureau G, Thibaud E, Kuttenn F. Breast Disease in Adolescents. Endocr Dev 2004;7:183–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michala L, Tsigginou A, Zacharakis D, Dimitrakakis C. Breast Disorders in Girls and Adolescents. Is There a Need for a Specialized Service? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2015;28(2):91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.