Abstract

Background:

Homeless youth in the United States have high rates of substance use. Existing research has identified social network composition and street-associated stressors as contributing factors. Incarceration is a highly prevalent stressor for homeless youth. Its effect on youth’s social network composition and substance use, however, has been neglected.

Aims:

This study investigated the direct and indirect associations between incarceration history and substance use (through social networks) among homeless youth in Los Angeles, California.

Methods:

A sample of 1,047 homeless youths were recruited between 2011 and 2013. Computerized self-administrated surveys and social network interviews were conducted to collect youth’s sociodemographic characteristics, incarceration history, social network composition, and substance use. Bootstrapping was used to identify the direct and indirect associations between youth’s incarceration history and substance use.

Results:

Incarceration history was positively associated with youth’s cannabis, methamphetamine, and injection drug use. The percentage of cannabis-using peers partially mediated the associations between incarceration history and youth’s cannabis, cocaine, and heroin use. The percentage of methamphetamine-using peers partially mediated the associations between incarceration history and youth’s methamphetamine, cocaine, and injection drug use. The percentage of heroin-using peers partially mediated the association between incarceration history and youth’s heroin use. Moreover, the percentage of peers who inject drugs partially mediated the associations between incarceration history and youth’s methamphetamine, heroin, and injection drug use.

Discussion:

Incarceration history should be taken to a more central place in future research and practice with homeless youth in the United States.

Keywords: Incarceration, Homeless Youth, Peer Influence, Social Network, Substance Use

Introduction

In the United States, approximately 1.6 million youths run away from home each year (1). Homeless youth are typically defined as unaccompanied persons age 12 and older up to age 17, 21, or 25 who live in shelters, on the streets, or in other unstable living conditions without family support (2,3). Studies have consistently shown that homeless youth have considerably higher rates of substance use compared to their housed counterparts (4,5). Though some youth initiated substance use before homelessness (6), the rate of substance use usually increases after they leave home (7). Researchers have attributed the elevated rate of substance use to the influence of other homeless peers who have substance use problems, the lack of prosocial agents in their social networks, and stressors related to street life (8-11). Incarceration is a highly prevalent stressor among homeless youth (12-14). Its potential effect on youth’s social network composition and substance use (4,5,9,12-15), however, has been largely neglected. This study investigated the direct and indirect associations between incarceration and substance use through social network composition with a sample of homeless youth in Los Angeles, California.

Homeless youth are at high risk for a number of adverse health and mental health problems, especially substance use (8,16). The high prevalence of substance use among homeless youth may be due to changes in their social network composition of peers who use substances and prosocial agents. Many homeless youth come from dysfunctional families that set them on a negative developmental trajectory (17). Becoming homeless further associates these youth in deviant networks (16). As time on the street increases, they are more likely to be embedded in street-based risk-taking-prone networks and disengaged from supportive prosocial networks (16,18). Social network changes can, in turn, impact homeless youth’s substance use. Research has shown that homeless youth with a higher number or density of network members who use substances report greater substance consumption (8,16,19). Homeless youth with a lower density of prosocial agents in social networks, including relatives, home-based peers, and caring adults (e.g., agency staff), report increased substance use (19).

In addition to social network changes, youth’s exposure to stressors related to street life also contributes to their substance use. Many homeless youth find themselves lonely and lacking emotional support as they attempt to deal with life on the streets (20). Substances are then used as an escaping mechanism to facilitate coping with an abusive environment and to alleviate feelings of isolation and loneliness (10). Moreover, some homeless youth report using substances to keep warm or suppress appetite (21).

Incarceration is highly prevalent among homeless youth (more than 60%) and may be an important factor related to their substance use (12,13). Many incarcerated youth have existing substance use problems prior to incarceration as drug-related incarceration soared since the War on Drugs initiated in the 1970s (22). The high levels of stress during confinement and enduring stigma after release (23,24) may also trigger or exacerbate homeless youth’s use of substances as a coping strategy (25,26). Research with homeless adults found that those with incarceration history are more likely to use substances (15), or have substance use disorders (4,5). For example, Kriegel and colleagues found that homeless women with incarceration history have higher rates of crack or cocaine use than homeless women without incarceration history (15). The association between incarceration history and substance use among homeless youth, however, remains understudied (14). To our knowledge, the only attempt to understand this association was from Nyamathi and colleagues who studied 156 homeless youths in California. That study did not find any significant relationship between incarceration history and the severity of drug use (14).

Besides its direct association with substance use, incarceration may have an indirect association with homeless youth’s substance use through their social network composition (9). Mainly due to the stricter sentencing of drug-related crimes, correctional facilities have had increased concentration of offenders with substance use problems (20,22). Teplin and colleagues found that approximately one half of incarcerated youth have one or more substance use disorders (27,28). The confinement environment may interrupt youth’s connections with prosocial agents(29), and provide a context for youth to establish contacts with those who use substances (22). Social isolation and limited social capital after release may drive youth to reconnect with new network members whom they engaged with during incarceration or return to their previous street networks with members who use substances, and further disengage from prosocial agents (22,30). Due to peer influence and peer contagion (25,31,32), exposure to a high concentration of network members who use substances may increase youth’s risk of developing or relapsing to substance use. Further, the lack of monitoring and caring prosocial agents may be associated with youth’s increased substance use (19). Kriegal and colleagues found that incarceration history is indirectly related to substance use through social network changes among homeless women (15). The indirect association between homeless youth’s incarceration history and substance use through social network composition, however, remains unexplored.

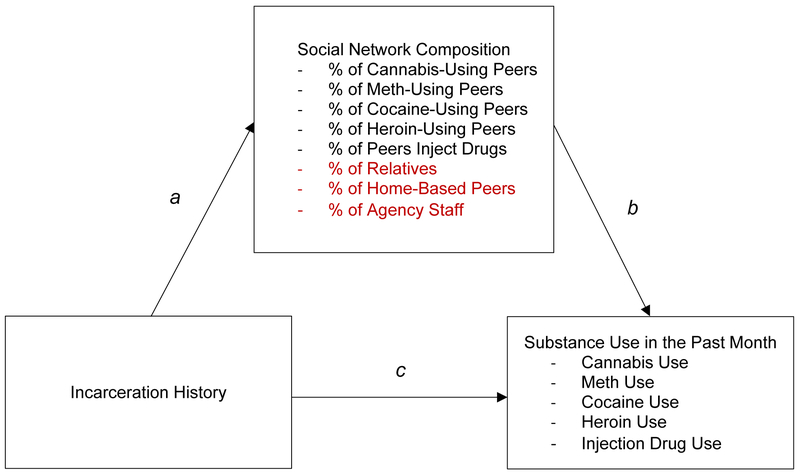

In this study, we used the Risk Amplification and Abatement Model (RAAM) to guide the investigation of the direct and indirect associations between incarceration history and homeless youth’s substance use (9). Developed specifically for homeless youth, the RAAM posits that homeless youth are substantially influenced by socializing agents across multiple levels of the social organization including peers, families, social services, and formal institutions (e.g., correctional facilities) (9). Negative contact with socializing agents amplify risk, while positive contact with prosocial agents abates risk (9). Guided by the RAAM, we hypothesized that 1) Homeless youth with incarceration history would report higher rates of past-month substance use (i.e., cannabis, methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and injection drug use) compared to their counterparts without incarceration history; and 2) Social network composition (i.e., % of substance-using peers and prosocial agents) would mediate the positive association between incarceration history and substance use among homeless youth. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework: The Direct and Indirect Associations Between Incarceration History and Youth’s Substance Use Through Their Social Network Composition.

Methods

Participants and Study Design

A sample of 1,047 homeless youths aged 13 to 25 were surveyed between October 2011 and June 2013. Participants were recruited from three drop-in centers for homeless youth in the County of Los Angeles: Hollywood, Santa Monica, and Venice, California. These drop-in centers provide services to eligible homeless youth, including basic needs, physical and mental health services, case management, and referrals to other programs such as housing services (3). All youth accessing services during the period of data collection were eligible and invited to participate in the study. Approximately 85% of the youth approached at the Hollywood site agreed to participate in the study. At Santa Monica and Venice sites, an average of 78% of the youth approached agreed to participate in the study.

After providing written informed consent, participants completed a computerized self-administered survey and a social network interview. Through the self-administered survey, participants responded to 200 questions assessing their attributes and behaviors (33). Through face-to-face social network interview conducted by trained research staff members (2), participants were asked to enumerate a list of contacts that they interacted with in the past month utilizing free recall name generators (a question or a series of questions designed to elicit the name of relevant social connections) (34,35). Participants then answered questions regarding the attributes of nominated contacts, including their substance use in the past month based on participants’ perceptions and relationship with the participants. All participants received $20 in cash or gift cards as compensation for their time. The research protocol received full approval from the [Blinded for Review] Internal Review Board (UP-10-00468) in October 2010. Detailed sampling procedure can be found elsewhere (2).

Measures

Incarceration history.

Participants reported their lifetime incarceration history (i.e., “Have you ever spent time in a jail, prison, juvenile detention center, or other correctional facilities?”). Those who responded “Yes” were classified as with incarceration history (1 = Yes, 0 = No).

Substance Use in the Past Month.

Participants were asked about their frequency of use regarding each type of substance in the past month, including cannabis, methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and injection drugs. A variable was created for each type of substance to represent how often participants have used that type of substance.

Social Network Composition.

Participants reported substance use (i.e., cannabis, methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and injection drug use) of each nominated contact in the past month and whether the nominated contact is a relative, home-based peer, or agency staff. We divided the number of nominated peers using that specific type of substance by participants’ network size to get the percentage of peers using each type of substance. We created variables of the percentage of social network members who are relatives, home-based peers, and agency staff using the same method.

Sociodemographic Characteristics.

Analysis controlled for a range of sociodemographic characteristics associated with incarceration, social network composition, and substance use, including age, gender, racial/ethnic background, sexual orientation, homeless age, homeless duration, and current living condition. According to a comprehensive definition of homelessness by Tsemberis and colleagues (36), youth staying in an emergency or temporary shelter, a stranger’s home, a hotel, a motel, on the street, on the beach, in a tent or composite, or in an abandoned building, a car, or a bus were categorized as literally homeless. Youth staying in a group home, a sober living facility, in jail, prison, or juvenile detention center, in a hospital or mental healthcare facility, in a transitional living program, or in a friend or family home were categorized as temporarily housed.

Data Analysis

Data analysis proceeded in the following steps. First, we cleaned the data and assessed missing values (0% - 14.5% missingness). We imputed missing values using Expectation-Maximization with all variables in the study (37,38). Second, we assessed the frequency distributions of homeless youth’s sociodemographic characteristics, incarceration history, social network composition, and substance use. Bivariate analysis (i.e., chi-square test and t-test) examined whether incarceration history, social network composition, and substance use varied by sociodemographic characteristics. Third, SAS PROCESS Macro (39) was used with bootstrapping (1000) (40,41) to estimate the direct and indirect associations between incarceration history and youth’s substance use through social network composition. Two separate models were tested: a) substance use within social networks as mediators between incarceration and youth’s substance use, and b) prosocial agents in social networks as mediators between incarceration and youth’s substance use. Bootstrapped estimates of mediation effects and their 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were obtained. Unless otherwise indicated, the significance level (two-tailed) was set at p < .05.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 illustrates participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, incarceration history, social network composition, and substance use. Participants’ age ranged from 14 to 29, with an average of 21 years old. Majority of the participants were male. White Americans comprised the largest racial/ethnic category, followed by African Americans, Latino Americans, and Other. The Other group comprised American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or mixed race. About a quarter of the participants self-identified as LGBTQ. The average age participants became homeless was 17. Majority of the participants had been homeless for more than 50 months and were literally homeless at the time of data collection. Further, almost two-thirds of participants had incarceration history. More than three-quarters of participants reported cannabis use in the past month, followed by methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and injection drug use. Cannabis was also the most prevalently used drug (more than 50%) in participants’ social networks, followed by methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and injection drug use. On average, participants reported 20% relatives, 38% home-based peers, and 6% agency staff in their social networks.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics, Incarceration History, Social Network Composition, and Substance Use in the Past Month Among Homeless Youth in Los Angeles, 2011-2013 (N=1,047).

| Variables | % | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||

| Age | - | - | 21.41 | 2.24 |

| < 21 Years Old | 38.01 | 398 | - | - |

| ≥ 21 Years Old | 61.99 | 649 | - | - |

| Male | 70.58 | 739 | - | - |

| Racial/Ethnicity | ||||

| White American | 38.77 | 406 | - | - |

| African American | 23.79 | 249 | - | - |

| Latino American | 13.56 | 142 | - | - |

| Other | 23.88 | 250 | - | - |

| Sexual Orientation -LGBTQ | 27.51 | 288 | - | - |

| Homelessness Status | ||||

| Literal Homeless | 62.56 | 655 | - | - |

| Temporarily Housed | 37.44 | 392 | - | - |

| Homeless Age | - | - | 16.85 | 4.13 |

| Homeless Duration (In Months) | - | - | 51.24 | 190.24 |

| Incarceration History – Ever Incarcerated | 63.31 | 663 | - | - |

| Social Network Composition | ||||

| % of Cannabis-Using Peers | - | - | 51.45 | 35.45 |

| % of Meth-Using Peers | - | - | 7.60 | 17.66 |

| % of Cocaine-Using Peers | - | - | 3.18 | 9.95 |

| % of Heroin-Using Peers | - | - | 2.24 | 8.23 |

| % of Peers Inject Drugs | - | - | 3.26 | 9.84 |

| % of Relatives | - | - | 20.17 | 20.14 |

| % of Home-Based Peers | - | - | 37.87 | 29.89 |

| % of Agency Staff | - | - | 5.99 | 12.44 |

| Substance Use in the Past Month | ||||

| Cannabis | 76.40 | 800 | - | - |

| Meth | 26.50 | 278 | - | - |

| Cocaine | 17.85 | 187 | - | - |

| Heroin | 12.16 | 127 | - | - |

| Injection Drugs | 10.99 | 115 | - | - |

Results of bivariate analyses described differences in incarceration experience, substance use, and social network composition by sociodemographic characteristics. Youth under age 21 were significantly less likely to report incarceration history and substance use, and had significantly more prosocial agents, compared to those 21 or older. Male youth had significantly higher prevalence of incarceration and substance use, and fewer substance-using peers and prosocial agents in social networks compared to female youth. Relative to heterosexual youth, LGBTQ youth had significantly lower prevalence of incarceration and cannabis, cocaine, and heroin use, but higher prevalence of methamphetamine use. They had significantly more agency staff, but more peers using methamphetamine, cocaine, and injection drugs in networks.

Further, incarceration history was most prevalent among White youth compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Relative to White youth, African American youth and youth in the Other racial/ethnic group had lower prevalence of substance use; Latino youth had significantly lower prevalence of cannabis, heroin, and injection drug use, but higher prevalence of cocaine use. African American youth had significantly fewer substance-using peers and more prosocial agents in their networks; Latino youth had significantly fewer substance-using peers (except for cocaine use) and more prosocial agents in their networks; and youth in the Other race/ethnic group reported significantly fewer peers using substances (except for methamphetamine), fewer relatives, but more agency staff in their social networks, compared to White youth.

Moreover, compared to temporarily housed youth, literally homeless youth had significantly lower prevalence of incarceration, and cannabis and methamphetamine use, higher prevalence of cocaine and heroin use, and fewer substance-using peers in their networks. Additionally, youth who became homeless before age 18 and those who had been homeless for at least one year (42) had higher prevalence of incarceration history and substance use, and significantly more substance-using peers and fewer prosocial agents (except agency staff) in their networks, in relative to those who became homeless at age 18 or older and those who experienced homelessness less than a year, respectively.

Multivariate Analysis

Direct Associations.

Partially consistent with research hypothesis 1, Table 2A and Table 2B show the direct association between incarceration history and youth’s substance use in the past month (path c in Figure 1). Controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, incarceration history was positively associated with youth’s cannabis, methamphetamine, and injection drug use.

Table 2A.

Direct Association Between Incarceration History and Youth’s Substance Use (Path c in Figure 1), and Direct Association Between Social Network Composition of Peers Using Substances and Youth’s Substance Use (Path b in Figure 1) in Los Angeles, 2011-2013 (N=1,047).

| Variables | Past Month Cannabis Use | Past Month Meth Use | Past Month Cocaine Use | Past Month Heroin Use | Past Month Inject Drug Use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | |

| Incarceration History (Ref: No) | .60 (.12)*** | .36, .84 | .24 (.07)*** | .10, .38 | .12 (.06) | >−.01, .24 | .01 (.05) | −.09. .11 | .08 (.03)** | .02, .14 |

| Social Network Composition | ||||||||||

| % of Cannabis-Using Peers | 2.41 (.17)*** | 2.08, 2.76 | .14 (.10) | −.06, .34 | .19 (.09)** | .02, .35 | .22 (.07)*** | .07, .36 | −.05 (.04) | −.14, .04 |

| % of Meth-Using Peers | −.40 (.38) | −1.14, .34 | 2.53 (.22)*** | 2.01, 2.96 | .45 (.19)** | .08, .82 | .05 (.16) | −.27, .37 | .24 (.10)** | .05, .43 |

| % of Cocaine-Using Peers | .16 (.61) | −1.04, 1.36 | .47 (.36) | −.24, 1.17 | 1.59 (.31)*** | .99, 2.19 | .67 (.26)** | .16, 1.19 | .02 (.16) | −.29, .32 |

| % of Heroin-Using Peers | .18 (.92) | −1.64, 1.99 | −.85 (.55) | −1.92, .22 | .22 (.46) | −.68, 1.13 | 1.77 (.40)*** | .99, 2.56 | .42 (.24) | −.05, .89 |

| % of Peers who Inject Drugs | −.52 (.84) | −2.16, 1.13 | 1.81 (.50)*** | .84, 2.78 | .30 (.42) | −.52, 1.13 | 1.81 (.36)*** | 1.10, 2.52 | 1.89 (.22)*** | 1.47, 2.32 |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age (Ref: ≥ 21 years old) | −.08 (.12) | −.31, .15 | .09 (.07) | −.04, .23 | .07 (.06) | −.04, .19 | .06 (.05) | −.04, .15 | .07 (.03)** | .01, .13 |

| Gender (Ref: Female) | .43 (.13)*** | .18, .69 | .23 (.08)*** | .08, .38 | −.05 (.07) | −.17, .08 | .04 (.06) | −.07, .15 | <.01 (.03) | −.06, .07 |

| Racial/Ethnicity (Ref: White American) | ||||||||||

| African American | −.76 (.15)*** | −1.05, −.47 | −.02 (.09) | −.19, .15 | .01 (.07) | −.13, .16 | −.05 (.06) | −.18, .07 | −.08 (.04)** | −.16, −.01 |

| Latino American | −.76 (.15)*** | −1.05, −.46 | .14 (.11) | −.07, .34 | .17 (.09) | −.01, .34 | .10 (.08) | −.05, .25 | .05 (.05) | −.04, .14 |

| Other | −.27 (.15) | −.55, .01 | −.04 (.09) | −.20, .14 | .11 (.07) | −.03, .25 | −.16 (.06)** | −.28, −.04 | −.03 (.04) | −.11, .04 |

| LGBTQ (Ref: Heterosexual) | .14 (.13) | −.11, .39 | .18 (.08)** | .03, .33 | −.10 (.06) | −.22, .03 | −.06 (.06) | −.17, .05 | .01 (.03) | −.06, .07 |

| Literally Homeless (Ref: No) | −.11 (.11) | −.33, .12 | .05 (.07) | −.08, .18 | .16 (.06)*** | .05, .27 | .16 (.05) ** | .06, .26 | <−.01 (.03) | −.06, .07 |

| Homeless Age | .02 (.02) | −.02, .04 | −.02 (<.01) ** | −.04, >−.01 | −.01 (.01) | −.03, <.01 | −.01 (.01) | −.02, <.01 | −.01 (<.01) ** | −.01, <.01 |

| Homeless Duration | <.01 (<.01) | >−.01, <.01 | <.01 (<.01) *** | <.01, <.01 | .01 (<.01) ** | <.01, <.01 | .01 (<.01) *** | <.01, <.01 | <.01 (<.01) | >−.01, <.01 |

| R2 | .27 | .25 | .09 | .20 | .22 | |||||

Note: Coefficients and Standard Errors (SE) are unstandardized; Ref = reference group

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 2B.

Direct Association Between Incarceration History and Youth’s Substance Use (Path c in Figure 1), and Direct Association Between Social Network Composition of Prosocial Agents and Youth’s Substance Use (Path b in Figure 1) in Los Angeles, 2011-2013 (N=1,047).

| Variables | Past Month Cannabis Use | Past Month Meth Use | Past Month Cocaine Use |

Past Month Heroin Use | Past Month Inject Drug Use |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | Coefficient (SE) |

95% CI | |

| Incarceration History (Ref: No) | .73 (.13)*** | .48, .98 | .40 (.08)*** | .24, .55 | .17 (.06)*** | .05, .29 | .10 (.06) | −.01. .21 | .13 (.03)*** | .06, .20 |

| Social Network Composition | ||||||||||

| % of Relatives | −.20 (.38) | −.93, .55 | −.19 (.23) | −.64, .26 | .28 (.18) | −.07, .63 | .09 (.16) | .23, .41 | −.02 (.10) | −.22, .18 |

| % of Home-Based Peers | −.28 (.25) | −.78, .21 | −.24 (.15) | −.54, .06 | −.11 (.12) | −.35, .12 | −.08 (.11) | −.30, .13 | −.06 (.07) | .19, .07 |

| % of Agency Staff | −2.41 (.52)*** | −3.42, −1.40 | −.69 (.31)** | −1.31, −.08 | −.36 (.25) | −.84, 1.12 | −.48 (.22)** | −.92, −.05 | −.03 (.14) | −.30, .23 |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age (Ref: ≥ 21 years old) | −.11 (.13) | −.36, .14 | .08 (.08) | −.07, .22 | .07 (.06) | −.05, .18 | .04 (.05) | −.07, .14 | .06 (.03) | >−.01, .13 |

| Gender (Ref: Female) | .46 (.14)*** | .19, .74 | .10 (.09) | −.07, .27 | −.07 (.07) | .20, .06 | −.01 (.06) | −.13, .11 | −.04 (.04) | −.11, .03 |

| Racial/Ethnicity (Ref: White American) | ||||||||||

| African American | −1.17 (.16)*** | −1.47, −.86 | −.21 (.09)** | −.39, −.02 | −.09 (.07) | −.23, .06 | −.22 (.07)*** | −.35, −.09 | −.17 (.04)*** | −.25, −.09 |

| Latino American | −1.14 (.19)*** | −1.52, −.77 | .13 (.11) | −.10, .35 | .16 (.09) | −.01, .34 | .01 (.08) | −.15, .17 | .01 (.05) | −.09, .11 |

| Other | −.35 (.16)** | −.65, −.04 | −.02 (.09) | −.20, .17 | .10 (.07) | −.05, .24 | −.22 (.07)*** | −.36, −.09 | −.06 (.04) | −.15, .02 |

| LGBTQ (Ref: Heterosexual) | .12 (.14) | −.15, .40 | .20 (.08)** | .03, .37 | −.09 (.07) | −.22, .04 | −.06 (.06) | −.18, .06 | .01 (.03) | −.06, .08 |

| Literally Homeless (Ref: No) | −.19 (.12) | −.43, .05 | −.01 (.07) | −.16, .13 | .13 (.06)** | .02, .25 | .11 (.05)** | .01, .22 | −.03 (.03) | −.09, .03 |

| Homeless Age | <.01 (.02) | −.03, .03 | −.03 (.01)*** | −.05, −.01 | −.01 (.01)** | −.03, >−.01 | −.01 (.01) | −.02, <.01 | −.01 (<.01) | −.01, <.01 |

| Homeless Duration | <.01 (<.01) | >−.01, <.01 | <.01 (<.01)*** | <.01, <.01 | .01 (<.01)*** | <.01, <.01 | .01 (<.01)*** | <.01, <.01 | <.01 (<.01) | >−.01, <.01 |

| R2 | .15 | .08 | .04 | .06 | .05*** | |||||

Note: Coefficients and Standard Errors (SE) are unstandardized; Ref = reference group

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 3A and Table 3B present the direct association between incarceration history and youth’s social network composition. Controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, youth with incarceration history reported a significantly higher percentage of network members using cannabis, methamphetamine, heroin, or injection drugs (path a in Figure 1). No significant association was observed between incarceration history and the percentage of prosocial agents in youth’s social networks.

Table 3A.

Direct Association Between Incarceration History and Social Network Composition of Peers Using Substances (Path a in Figure 1) Among Homeless Youth in Los Angeles, 2011-2013 (N=1,047).

| Variables | % of Relatives | % of Home-Based Peers | % of Agency Staff | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Incarceration History (Ref: No) | .02 (.01) | −.01, .04 | −.03 (.02) | −.07, <.01 | <.01 (.01) | −.01, .02 |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Age (Ref: ≥ 21 years old) | −.01 (.01) | −.03, .02 | −.01 (.02) | −.05, .02 | <.01 (.01) | −.01, .02 |

| Gender (Ref: Female) | −.03 (.01)** | −.06, >−.01 | −.05 (.02)** | −.09, −.01 | −.01 (.01) | −.02, .01 |

| Racial/Ethnicity (Ref: White American) | ||||||

| African American | .06 (.02)*** | .03, .09 | .05 (.02) ** | .01, .10 | .05 (.01)*** | .03, .07 |

| Latino American | .04 (.02) | >−.01, .07 | .05 (.03) | −.01, .10 | .05 (.01)*** | .02, .07 |

| Other | −.02 (.02) | −.05, .01 | <.01 (.01) | −.04, .05 | .04 (.01)*** | .03, .06 |

| LGBTQ (Ref: Heterosexual) | −.01 (.01) | −.04, .02 | −.06 (.02)*** | −.10, −.02 | >−.01 (.01) | −.02, .02 |

| Literally Homeless (Ref: No) | .03 (.01)** | <.01, .05 | .03 (.02) | −.01, .06 | −.02 (.01)*** | −.03, −.01 |

| Homeless Age | <−.01 (<.01) | >−.01, .01 | .01 (<.01)*** | <.01, .01 | >−.01 (<.01) ** | >−.01, >−.01 |

| Homeless Duration | <.01 (<.01) | >−.01, <.01 | <.01 (<.01) | >−.01, <.01 | .01 (<.01) | <.01, <.01 |

| R2 | .04 | .04 | .05 | |||

Note: Coefficients and Standard Errors (SE) are unstandardized; Ref = reference group

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 3B.

Direct Association between Incarceration History and Social Network Composition of Prosocial Agents (Path a in Figure 1) Among Homeless Youth in Los Angeles, 2011-2013 (N=1,047).

| Variables | % of Relatives | % of Home-Based Peers | % of Agency Staff | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Incarceration History (Ref: No) | .02 (.01) | −.01, .04 | −.03 (.02) | −.07, <.01 | <.01 (.01) | −.01, .02 |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Age (Ref: ≥ 21 years old) | −.01 (.01) | −.03, .02 | −.01 (.02) | −.05, .02 | <.01 (.01) | −.01, .02 |

| Gender (Ref: Female) | −.03 (.01)** | −.06, >−.01 | −.05 (.02)** | −.09, −.01 | −.01 (.01) | −.02, .01 |

| Racial/Ethnicity (Ref: White American) | ||||||

| African American | .06 (.02)*** | .03, .09 | .05 (.02) ** | .01, .10 | .05 (.01)*** | .03, .07 |

| Latino American | .04 (.02) | >−.01, .07 | .05 (.03) | −.01, .10 | .05 (.01)*** | .02, .07 |

| Other | −.02 (.02) | −.05, .01 | <.01 (.01) | −.04, .05 | .04 (.01)*** | .03, .06 |

| LGBTQ (Ref: Heterosexual) | −.01 (.01) | −.04, .02 | −.06 (.02)*** | −.10, −.02 | >−.01 (.01) | −.02, .02 |

| Literally Homeless (Ref: No) | .03 (.01)** | <.01, .05 | .03 (.02) | −.01, .06 | −.02 (.01)*** | −.03, −.01 |

| Homeless Age | <−.01 (<.01) | >−.01, .01 | .01 (<.01)*** | <.01, .01 | >−.01 (<.01) ** | >−.01, >−.01 |

| Homeless Duration | <.01 (<.01) | >−.01, <.01 | <.01 (<.01) | >−.01, <.01 | .01 (<.01) | <.01, <.01 |

| R2 | .04 | .04 | .05 | |||

Note: Coefficients and Standard Errors (SE) are unstandardized; Ref = reference group

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Moreover, social network composition was directly related to homeless youth’s substance use (path b in Figure 1). As is shown in Table 2A, peer’s cannabis use was positively associated with youth’s cannabis, cocaine, and heroin use. Peer’s methamphetamine use was associated with youth’s methamphetamine, cocaine, and injection drug use. Peer’s cocaine use was associated with youth’s cocaine and heroin use. Peer’s heroin use was associated with youth’s heroin use. Peer’s injection drug use was positively associated with youth’s methamphetamine, heroin, and injection drug use. Moreover, the percentage of agency staff in youth’s social networks was negatively associated with youth’s cannabis, methamphetamine, and heroin use (see Table 2B).

Indirect Associations.

Partially consistent with research hypothesis 2, social network composition mediated the association between incarceration history and substance use (Table 4). Specifically, the percentage of cannabis-using peers partially mediated the associations between youth’s incarceration history and cannabis, cocaine, and heroin use. The percentage of methamphetamine-using peers partially mediated the associations between youth’ incarceration history and methamphetamine, cocaine, and injection drug use. The percentage of heroin-using peers partially mediated the association between youth’s incarceration history and heroin use. Moreover, the percentage of peers who injected drugs partially mediated the associations between youth’s incarceration history and methamphetamine, heroin, and injection drug use. We did not observe any significant mediation effect of prosocial agents in social networks linking the association between incarceration and youth’s substance use.

Table 4.

Indirect Effects of Social Network Composition in Mediating the Relationship Between Incarceration History and Substance Use in the Past Month Among Homeless Youth in Los Angeles, 2011-2013 (N=1,047).

| Path | Path Coefficient | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Cannabis-Using Peers → Cannabis Use in the Past Month | .15 | .06 | .25 |

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Meth-Using Peers → Meth Use in the Past Month | .08 | .03 | .14 |

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Peers who Inject Drugs → Meth Use in the Past Month | .03 | <.01 | .07 |

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Cannabis-Using Peers → Cocaine Use in the Past Month | .01 | <.01 | .03 |

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Meth-Using Peers → Cocaine Use in the Past Month | .02 | <.01 | .04 |

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Cannabis-Using Peers → Heroin Use in the Past Month | .01 | <.01 | .03 |

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Heroin-Using Peers → Heroin Use in the Past Month | .02 | .01 | .05 |

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Peers who Inject Drugs → Heroin Use in the Past Month | .03 | .01 | .07 |

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Meth-Using Peers → Injection Drug Use in the Past Month | .01 | <.01 | .02 |

| Ever Incarcerated → % of Peers who Inject Drugs → Injection Drug Use in the Past Month | .03 | .01 | .06 |

Note: Coefficients and Standard Errors (SE) are unstandardized. All hypothesized mediation paths in Figure 1 were tested; only significant mediation paths were presented in this table.

Discussion

Findings regarding the relationships between incarceration history and substance use among homeless youth partially support stated hypotheses. Findings revealed that incarceration history was positively associated with homeless youth’s substance use in the past month. Moreover, substance use within social networks mediated the association between incarceration history and youth’s use of certain substances.

Inconsistent with findings from Nyamathi’s study (14), our results suggested a positive association between incarceration history and cannabis, methamphetamine, and injection drug use among homeless youth. Due to the high concentration of youth with substance use problems in the correctional facilities (27,28), new connections established during confinement might have introduced youth to substance use or reinforced their preexisting use. Some youth might have learned to use substances during confinement from newly connected deviant social network members who use substances. For youth who had developed substance use prior to their incarceration, the stress and stigma associated with incarceration and peer influence might have exacerbated their existing substance use. To reduce youth’s substance use, alternatives to incarceration such as juvenile drug courts that prevent youth from being influenced by a more high risk network may be considered (43,44). To address stressors that come after release, reentry programs such as intensive aftercare programs that focus on reintegration during incarceration and a highly structured and gradual transition between institutions and aftercare are necessary to reduce youth’s substance use (45).

It is worth noting that incarceration history is directly associated with homeless youth’s social network composition. Specifically, we found that homeless youth with incarceration history reported significantly higher percentage of peers using cannabis, methamphetamine, heroin, and injection drugs compared to their counterparts without incarceration history. However, the association between incarceration and social network composition of cocaine users was nonsignificant. Due to the popularity of cocaine in Los Angeles among homeless youth, the influence of incarceration history on their use of this specific type of drug may have been diluted (21). In addition, findings of the association between incarceration and social network composition of peers who use substances suggest that incarceration history should be taken to a more central place in future research and practice with homeless youth, as peer influence is an established predictor of a constellation of risky behaviors among homeless youth such as HIV/AIDS risk behaviors (26,46).

Contributing to the existing literature, we found that substance use in social networks mediated the association between incarceration history and youth’s substance use. The significant mediating role of social network composition suggests the need for interventions that minimize high risk connections and facilitate prosocial connections (according to RAAM) (9). Though our findings did not reveal significant mediation effects of social network composition of prosocial agents, the negative association between the percentage of agency staff in networks and youth’s substance use suggests that interventions that use network technologies to help youth stay in contact with agency staff may be valuable. Moreover, we found that the percentage of peers using a specific substance was not only positively related to homeless youth’s use of that particular substance but extended to youth’s use of other substances. For instance, homeless youth with a higher percentage of peers using injection drugs were significantly more likely to use methamphetamine and heroin in addition to injection drugs. As methamphetamine, cocaine, and heroin are often administered through injection among youth (47-49), peer-based interventions may be especially useful for substances administered through injection and should consider general substance use interventions that treat different types of substances sharing the same route of administration. It is essential to keep in mind that needle sharing with peers who also inject drugs is common among homeless youth (50), and it increases the risk of Hepatitis and HIV/AIDS infection (51). Therefore, it is necessary for peer-based interventions to address needle sharing among homeless youth specifically.

Findings of this study are subject to several limitations. First, these data are cross-sectional. Therefore, causal relationships between incarceration and substance use cannot be inferred without controlling for youth’s pre-incarceration substance use. Future studies using longitudinal data should examine the temporal order between incarceration history and substance use among homeless youth. Second, the dichotomized measure of incarceration history masks significant heterogeneities of homeless youth’s juvenile and criminal justice contacts such as the type of correctional facilities. As the effects of incarceration vary by the characteristics of incarceration (52-54), comprehensive longitudinal data on youth’s incarceration history that characterizes interpersonal changes over the life course and intrapersonal differences is essential to future exploration of the consequences of incarceration among this population. Third, name generator is subject to recall bias, as youth may have missed important social connections at the time of interview. Multiple elicitations, however, are the most viable solution to elicit nominations due to the lack of roster or other registries (33). Fourth, due to the lack of residential stability inherent to homelessness (21), data were drawn from a convenience sample of service-seeking homeless youth in Los Angeles, and are therefore subject to the bias inherent to this sampling strategy. The demographic profile of our sample, however, is comparable to a probability sample of homeless youth recruited in Los Angeles by RAND two years before our data collection (8). Lastly, as this sample was drawn from drop-in centers in Los Angeles, one should be cautious in generalizing the results beyond service-seeking homeless youth in Los Angeles.

This study represents an initial effort in exploring the effects of incarceration on substance use among homeless youth. Findings have recognized the importance and the need to incorporate incarceration history into future research and practice related to homeless youth. Specifically, findings have provided nuanced understanding vis-a-vis the direct and indirect effects of incarceration on substance use among homeless youth, which will contribute to the social network literature and provide practical guidance on substance use interventions targeting this population. Given the high prevalence of incarceration among homeless youth and the long-lasting adverse consequences associated with incarceration, more studies are needed to fully explore the effects of incarceration on the health and well-being of homeless youth, including substance use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding & Support

The research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [R01 MH093336]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Qianwei Zhao, USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, University of Southern California, 669 W 34th Street, MRF Bldg., Suite 214, Los Angeles, California 90089-0411, qianweiz@usc.edu, 215-460-0826.

B.K. Elizabeth Kim, USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, University of Southern California

Wen Li, School of Social Work, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

Hsin-Yi Hsiao, USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, University of Southern California

Eric Rice, USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, University of Southern California

References

- 1.Toro PA, Tompsett CJ, Lombardo S, Philippot P, Nachtergael H, Galand B, et al. Homelessness in Europe and the United States: A comparison of prevalence and public opinion. J Soc Issues 2007;63(3):505–524. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice E, Winetrobe H, Rhoades H. Estimate Project: An innovative method for enumerating unaccompanied homeless youth. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles 2013. April. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petering R, Rice E, Rhoades H. Violence in the social networks of homeless youths: Implications for network-based prevention programming. J Adolescent Res 2016;31(5):582–605. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushel MB, Hahn JA, Evans JL, Bangsberg DR, Moss AR. Revolving doors: imprisonment among the homeless and marginally housed population. Am J Public Health 2005;95(10):1747–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA. Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness. Psychiat Serv 2004;55(1):42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson MJ. Homeless youth: An overview of recent literature. Homeless children and youth: A new American dilemma 1991:33–68. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene JM, Ringwalt CL, Kelly J, Iachan R, Cohen Z. Youth with runaway, throwaway, and homeless experiences: Prevalence, drug use, and other at-risk behaviors. Research Triangle Institute; 1995;1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Golinelli D, Green HD, Zhou A. Personal network correlates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among homeless youth. Drug Alcohol Depen 2010;112(1):140–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milburn NG, Rice E, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mallett S, Rosenthal D, Batterham P, et al. Adolescents exiting homelessness over two years: The risk amplification and abatement model. J Res Adolescence 2009;19(4):762–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMorris BJ, Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Familial and” on-the-street” risk factors associated with alcohol use among homeless and runaway adolescents. J Stud Alcohol 2002;63(1):34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christiani A, Hudson AL, Nyamathi A, Mutere M, Sweat J. Attitudes of homeless and drug-using youth regarding barriers and facilitators in delivery of quality and culturally sensitive health care. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 2008;21(3):154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallett S, Rosenthal D, Myers P, Milburn N, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Practising homelessness: a typology approach to young people’s daily routines. J Adolescence 2004;27(3):337–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Grady B, Gaetz S. Homelessness, gender and subsistence: The case of Toronto street youth. J Youth Stud 2004;7(4):397–416. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nyamathi A, Hudson A, Greengold B, Slagle A, Marfisee M, Khalilifard F, et al. Correlates of substance use severity among homeless youth. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 2010;23(4):214–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kriegel LS, Hsu H, Wenzel SL. Personal networks: A hypothesized mediator in the association between incarceration and HIV risk behaviors among women with histories of homelessness. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 2015;6(3):407–432. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rice E, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mallett S, Rosenthal D. The effects of peer group network properties on drug use among homeless youth. Am Behav Sci 2005;48(8):1102–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Yoder KA. A risk 0090amplification model of victimization and depressive symptoms among runaway and homeless adolescents. Am J Commun Psychol 1999;27(2):273–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanlon TE, Blatchley RJ, Bennett-Sears T, O’Grady KE, Rose M, Callaman JM. Vulnerability of children of incarcerated addict mothers: Implications for preventive intervention. Child Youth Serv Rev 2005;27(1):67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice E, Milburn NG, Monro W. Social networking technology, social network composition, and reductions in substance use among homeless adolescents. Prev Sci 2011;12(1):80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rew L, Taylor‐Seehafer M, Thomas N. Without parental consent: Conducting research with homeless adolescents. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2000;5(3):131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bousman CA, Blumberg EJ, Shillington AM, Hovell MF, Ji M, Lehman S, et al. Predictors of substance use among homeless youth in San Diego. Addict Behav 2005;30(6):1100–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Travis J, Western B, Redburn FS. The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umez C, Borowsky I, Eisenberg M. 154. Correlates of Stress Among Youth in Correctional Facilities. J Adolescent Health 2011;48(2):S97. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fader JJ. Conditions of a successful status graduation ceremony: Formerly incarcerated urban youth and their tenuous grip on success. Punishm Soc 2011;13(1):29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A, Walters RH. Social learning theory. : Prentice-hall Englewood Cliffs, NJ; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rice E, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Pro-social and problematic social network influences on HIV/AIDS risk behaviours among newly homeless youth in Los Angeles. AIDS Care 2007;19(5):697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, Mericle AA. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59(12):1133–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teplin LA, Elkington KS, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Mericle AA, Washburn JJ. Major mental disorders, substance use disorders, comorbidity, and HIV-AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees. Psychiat Serv 2005;56(7):823–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christian J Riding the bus: Barriers to prison visitation and family management strategies. J Contemp Crim Justice 2005;21(1):31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose DR, Clear TR. Incarceration, reentry, and social capital. Prisoners once removed: The impact of incarceration and reentry on children, families, and communities 2003:189–232. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dishion TJ, Dodge KA. Peer contagion in interventions for children and adolescents: Moving towards an understanding of the ecology and dynamics of change. J Abnorm Child Psych 2005;33(3):395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dishion TJ, Tipsord JM. Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annu Rev Psychol 2011;62:189–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petering R, Rice E, Rhoades H, Winetrobe H. The social networks of homeless youth experiencing intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence 2014;29(12):2172–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell KE, Lee BA. Name generators in surveys of personal networks. Soc Networks 1991;13(3):203–221. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marsden PV. Recent developments in network measurement. Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis 2005;8:30. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health 2004;94(4):651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the royal statistical society.Series B (methodological) 1977:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong Y, Peng CJ. Principled missing data methods for researchers. SpringerPlus; 2013;2(1):222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther 2017;98:39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kenny DA. Mediation. 2018; Available at: http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 41.Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication monographs 2009;76(4):408–420. [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Defining Chronic Homelessness: A Technical Guide for HUD Programs. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2007. September. [Google Scholar]

- 43.SAMHSA. Juvenile Drug Courts Help Youth Dealing With Trauma. 2016; Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/homelessness-programs-resources/hpr-resources/juvenile-drug-courts-help-youth.

- 44.Schaeffer CM, Henggeler SW, Chapman JE, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB, Randall J, et al. Mechanisms of effectiveness in juvenile drug court: Altering risk processes associated with delinquency and substance abuse. Drug Court Review 2010;7(1):57–94. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiebush RG, Wagner D, McNulty B, Wang Y, Le TN. Implementation and Outcome Evaluation of the Intensive Aftercare Program. Final Report. US Department of Justice; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baron SW, Hartnagel TF. Street youth and criminal violence. J Res Crime Delinq 1998;35(2):166–192. [Google Scholar]

- 47.How is Methamphetamine Abused? National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48.How is cocaine used? National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2016. May. [Google Scholar]

- 49.What is heroin and how it is used? National Institute of Drug Abuse; 2018. June. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kipke MD, O’connor S, Palmer R, MacKenzie RG. Street youth in Los Angeles: Profile of a group at high risk for human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Pediat Adol Med 1995;149(5):513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Todd CS, Abed AM, Strathdee SA, Scott PT, Botros BA, Safi N, et al. HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B infections and associated risk behavior in injection drug users, Kabul, Afghanistan. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13(9):1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schnittker J, Massoglia M, Uggen C. Out and down: Incarceration and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2012;53(4):448–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andersen LH. How children’s educational outcomes and criminality vary by duration and frequency of paternal incarceration. Ann Am Acad Polit S S 2016;665(1):149–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wildeman C, Turney K. Positive, negative, or null? The effects of maternal incarceration on children’s behavioral problems. Demography 2014;51(3):1041–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.