Abstract

Background

Nicotine and alcohol use are highly comorbid. Modulation of drug-paired extrinsic and intrinsic cues likely play a role in this interaction, as cues can acquire motivational properties and augment drug seeking. The motivational properties of cues can be measured through Pavlovian conditioning paradigms, in which cues either elicit approach following pairing with the reinforcing properties of alcohol, or elicit avoidance following pairing with the aversive consequences of alcohol. The present experiments tested whether nicotine would enhance the incentive properties of an appetitive ethanol-cue and diminish the avoidance of an aversive ethanol-cue in Pavlovian paradigms.

Methods

In experiment 1, male Long-Evans rats with or without prior chronic intermittent access to ethanol were administered nicotine or saline injections prior to Pavlovian conditioned approach (PavCA) sessions, during which conditioned approach to the cue (“sign-tracking”) or the ethanol delivery location (“goal-tracking”) were measured. In experiment 2, male Long-Evans rats were administered nicotine or saline injections prior to pairing a flavor cue with increasing doses of ethanol (i.p.) in an adaptation of the conditioned taste avoidance (CTA) paradigm.

Results

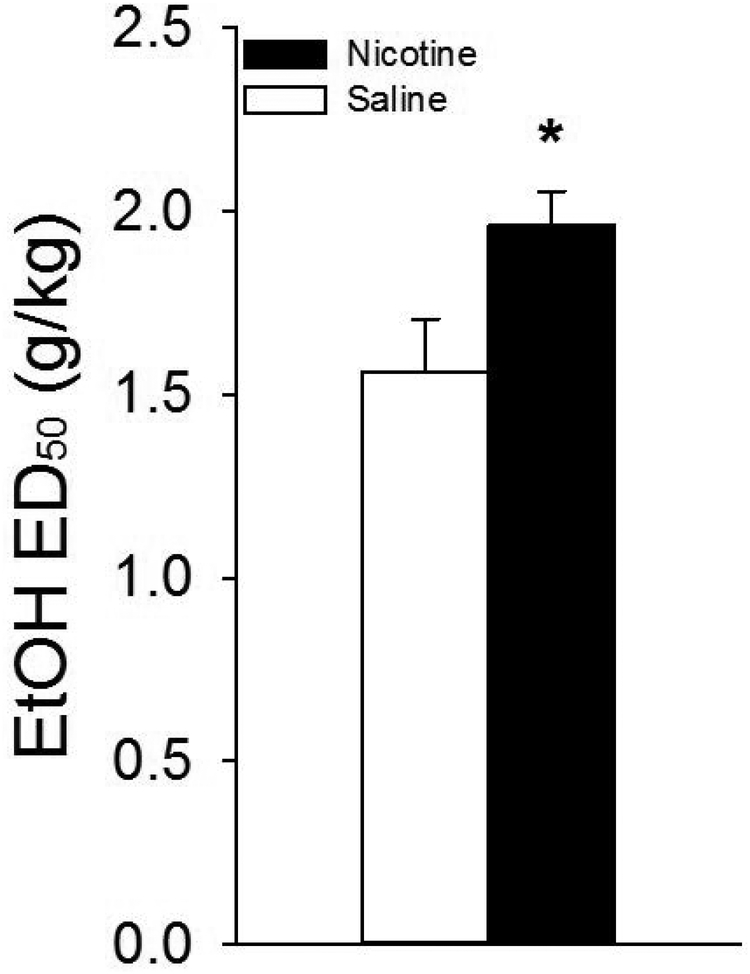

Results from PavCA indicate that, regardless of ethanol exposure, nicotine enhanced responding elicited by ethanol-paired cues with no effect on a similar cue not explicitly paired with ethanol. Furthermore, nicotine reduced sensitivity to ethanol-induced CTA, as indicated by a rightward shift in the dose-response curve of passively administered ethanol. The ED50, or the dose of ethanol that produced a 50% reduction in intake relative to baseline, was significantly higher in nicotine-treated rats compared to saline-treated rats.

Conclusions

We conclude that nicotine increases the approach and diminishes the avoidance elicited by Pavlovian cues paired, respectively, with the reinforcing and aversive properties of ethanol consumption in male rats. As such, nicotine may enhance alcoholism liability by engendering an attentional bias towards cues that predict the reinforcing outcomes of drinking.

Keywords: Alcohol, Nicotine, Pavlovian conditioning, Interoception, Autoshaping, Conditioned avoidance

Introduction

Smoking and alcohol drinking are highly comorbid; 43–72% of alcohol drinkers regularly smoke tobacco compared to only 15–23% of non-drinkers, and smokers are 2–4 times more likely to abuse alcohol than non-smokers (Weinberger et al., 2017b, Weinberger et al., 2017a). Clinical evidence supports a bidirectional relationship between nicotine and alcohol use, with increasing use of nicotine predicting greater degree of alcohol dependence, and vice-versa (Falk et al., 2006). In rodents, nicotine promotes operant ethanol self-administration (Bito-Onon et al., 2011, Doyon et al., 2013, Le et al., 2003), delays extinction of ethanol-seeking behavior (Le et al., 2010), reinstates ethanol-seeking (Le et al., 2003), and limits acquisition of ethanol-induced conditioned taste avoidance (CTA; Kunin et al., 1999, Loney and Meyer, 2019, Rinker et al., 2011, Bienkowski et al., 1998). Alcohol- and nicotine-associated stimuli (“cues”) likely play an important role in augmenting alcohol seeking. Paired cues can acquire motivational properties and either spur drug-seeking and self-administration (Katner et al., 1999, Corbit and Janak, 2007, Grusser et al., 2004, Tomie and Sharma, 2013, Wiers et al., 2009) or elicit avoidance responses when paired with aversive doses of a given drug (Liu et al., 2009, Loney and Meyer, 2019, Verendeev and Riley, 2011, Verendeev and Riley, 2013; Loney et al., 2018). Clinical models of cue-induced alcohol craving posit that approach and avoidance inclinations develop, respectively, as a function of the reinforcing and aversive consequences of alcohol use (Breiner et al., 1999, Schlauch et al., 2015). Furthermore, a high-approach/low-avoidance phenotype is associated with a tendency for risky drinking behaviors, an intractable attitude towards substance abuse treatment, and is positively correlated with both cue-elicited craving and alcohol consumption in a clinical setting (Stritzke et al., 2004, Schlauch et al., 2015, Hollett et al., 2017). As such, studies designed to explicitly measure the impact of the subjective aversive and reinforcing properties of commonly abused drugs are critical to understanding underlying neural mechanisms contributing to development of substance use disorders.

In preclinical models, the motivational properties of cues can be inferred using Pavlovian conditioned approach (e.g. PavCA) and avoidance paradigms (e.g. CTA), during which, respectively, an environmental cue predicts the delivery of a reward, such as a food pellet or ethanol solution (Milton and Everitt, 2010, Robinson and Berridge, 1993, Robinson et al., 2014) or a flavor cue predicts passive administraton of concentrated ethanol (Liu et al., 2009, Loney and Meyer, 2019, Rinker et al., 2011, Kunin et al., 1999, Bienkowski et al., 1998). In PavCA paradigms, due to the reinforcing value of the stimulus, in response to presentations of a predictive cue, rats generally display a tendency to approach either the cue itself (“sign-tracking”) or the reward delivery location (“goal-tracking”), even though no response is required to receive the reward. Such cue-reactivity elicited by drug-paired stimuli predicts other measures of incentive value, including conditioned reinforcement, cue-induced reinstatement, and the response to drug cues in multiple other paradigms (Flagel et al., 2010, Flagel et al., 2009, Versaggi et al., 2016, Robinson et al., 2014, Saunders and Robinson, 2010, Maddux and Chaudhri, 2017, Srey et al., 2015; Meyer et al., 2012). A number of recent studies have demonstrated the ability for ethanol-paired cues to elicit approach behaviors (Srey et al., 2015, Maddux and Chaudhri, 2017, Fiorenza et al., 2018). However, these studies found opposing effects on cue-reactivity, with one demonstrating an increase in sign-tracking over repeated ethanol exposures (Srey et al., 2015) and the other an increase in goal-tracking (Fiorenza et al., 2018). Nicotine has previously been shown to enhance ethanol cue-induced approach (Maddux and Chaudhri, 2017), though the design of that study was unable to differentiate whether nicotine preferentially increased sign- or goal- tracking. Because sign- and goal-tracking are thought to be resultant from differing psychological processes (i.e. Pavlovian mechanisms and cognitive expectation, respectively) these results raise questions about the means by which ethanol-cues influence behavior and, more specifically, how prior ethanol experience and nicotine administration interact to affect responding to ethanol-cues. Therefore, it is ultimately yet to be determined whether nicotine differentially affects goal- vs. sign-tracking to an ethanol cue and if the tendency for nicotine to enhance conditioned approach is dependent on previous ethanol experience.

Conversely, nicotine interferes with the degree of avoidance of an ethanol-paired cue in CTA paradigms (Bienkowski et al., 1998, Kunin et al., 1999, Rinker et al., 2011, Loney and Meyer, 2019). These CTA paradigms rely on the aversive interoceptive properties of a drug stimulus in order to modulate the motivational properties of a highly palatable stimulus (Rinker et al., 2011, Loney and Meyer, 2019). Thus far, the mechanisms underlying the ability for nicotine to interfere with ethanol-induced CTA are unknown. It could be that nicotine interferes with the cellular mechanisms underlying the acquisition of a CTA. Another possibility, is that nicotine specifically reduces the salience of the aversive stimulus properties of ethanol (Rinker et al., 2011). In this case, nicotine treated rats would be capable of acquiring a sufficient avoidance response relative to a saline-treated rat, they would simply require a higher dose in order to do so. The lack of an effect of nicotine on LiCl-induced CTA (Loney and Meyer, 2018) suggests this to be the case, but studies specifically testing the sensitivity of nicotine-treated, relative to saline-treated, rats to avoidance conditioned by a given dose of ethanol have yet to be conducted.

The present studies were designed to determine the impact of nicotine on sensitivity to the reinforcing properties of ethanol in male rats, as a function of previous ethanol drinking history, by examining its effects on approach to ethanol-paired cues in a discriminated PavCA paradigm wherein a cue explicitly paired with ethanol and a separate cue not paired with ethanol were presented within the same session. Furthermore, we also examined the impact of nicotine on the aversive properties of passively administered ethanol in an adaptation of the CTA paradigm where a flavor cue was paired with increasing doses of ethanol. We hypothesized that, regardless of previous ethanol experience, nicotine would facilitate approach to ethanol-associated cues with no impact on non-associated cues and that nicotine may interact with previous ethanol history to further spur ethanol-seeking behaviors. We also hypothesized that nicotine would reduce the sensitivity to the aversive consequences of ethanol administration as evidenced by a lateral shift in the ED50, indicating a general reduction in sensitivity for a given dose of ethanol to induce avoidance of a highly palatable saccharin solution. In summary, we show that nicotine administration in male rats produces a high-approach, low-avoidance phenotype towards ethanol-associated cues regardless of previous drinking experience.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and housing

A total of 59 male Long-Evans rats (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN; ~250–300g on arrival) were used across two separate experiments (Exp. 1: n = 34; Exp. 2: n = 25). Sample sizes were chosen based on effect sizes from previous studies (e.g. Loney and Meyer, 2019; Loney et al., 2018). Given that male and female rats differ in their sensitivity to the effects of nicotine (Chaudhri et al., 2005; Loney and Meyer, 2019), we focused on male rats for these initial phenomenological experiments. Rats were housed singly in polycarbonate cages (45 cm length × 24 cm width × 20 cm height) in a temperature and humidity controlled room (22±1°C) and maintained on a reverse 12-h light/dark cycle. Rats were handled daily for three days before testing began. Food and water were available ad libitum for the duration of experiment 1 and rats were maintained on 23.5 h water deprivation during experiment 2. All procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experiment 1: Effect of nicotine on ethanol cue-elicited approach during a discriminated Pavlovian (CS+ and CS-) approach paradigm

Apparatus

Pavlovian and operant conditioning occurred in Med-Associates chambers (St-Albans, VT; 30.5 × 24.1 cm floor area, 29.2 cm high) inside individual sound and light attenuating cabinets (A & B Displays, Bay City, MI) equipped with fans for ventilation and noise-masking. A red house light was located in the center panel of the left wall of the chamber for all experiments (27 cm above floor).

A retractable sipper bottle (Med Associates, Model ENV-252M) containing undenatured 200 proof ethanol diluted with tap water to a concentration of 20% (v/v; Decon Labs) was located opposite the house light, in the center panel of the right wall (6 cm above floor). Two retractable, illuminated levers (6 cm above floor) were positioned on either side of the bottle delivery port.

A contact detection system (Med Associates Model ENV-005-QD) was used to measure contacts with the levers and the faceplates of the lever casing (lever faceplate 7.6 cm W × 8.3 cm H), and contacts with the sipper bottle and its faceplate (sipper bottle faceplate 7.6 cm W × 16.5 cm H). In addition, levers were calibrated such that they were deflected by 15–20 g of pressure, and these deflections were included in lever contacts. All data were collected using MED-PC IV.2 software.

Chronic intermittent access to ethanol

One week after arrival, rats were assigned to either ethanol-exposed or ethanol-unexposed (water) groups. Exposed rats (n = 17) were tested in a chronic intermittent access to ethanol paradigm (CIA; Loney and Meyer, 2018a, Simms et al., 2008), during which rats were given access to two bottles containing either ethanol (20% v/v) or tap water for three 24-h sessions per week (Mon/Wed/Fri). Ethanol bottles were presented on alternating sides of the home-cage to prevent the development of a side preference. On the intervening days, both bottles contained water. Unexposed rats (n = 17) were given two sipper bottles containing water on all days. The procedure lasted 31 days, for a total of 14, 24-h ethanol drinking sessions. Changes in water and ethanol bottle weights were recorded to determine total fluid intake, total ethanol intake (g/kg/24 h; grams of ethanol consumed per kilogram of body weight over each 24-h session), and ethanol preference (%; ratio of grams of ethanol consumed to total grams of fluid consumed over each 24-hour session). To account for fluid loss due to evaporation or spillage, the data for each rat was adjusted by subtracting the average difference in bottle weight from pairs of control ethanol and water bottles placed onto two empty cages. Fluid intake was not recorded on Sat/Sun.

Ethanol Pavlovian conditioned approach

Following CIA, rats were trained in a Pavlovian conditioned approach (PavCA) paradigm (Fig. 1A). During PavCA testing, rats were assigned to receive either a nicotine (Glentham; 0.4 mg/kg, s.c., dose expressed as freebase, pH was adjusted to ~7.2–7.4,) or saline injection 15-min prior to testing. These nicotine- and saline-treated groups were matched based on ethanol preference during CIA to ethanol. Rats received one injection of their assigned drug the day before the first testing session to habituate them to the injection procedure. Testing occurred daily on Monday through Friday of each week for a total of 40 sessions which occurred over 8 weeks. During weeks 1–7 rats received the assigned nicotine or saline injection. In order to determine whether nicotine’s effects were acute or chronic, during week 8 all rats received saline treatments. Thus, week 8 is referred to as a nicotine removal condition.

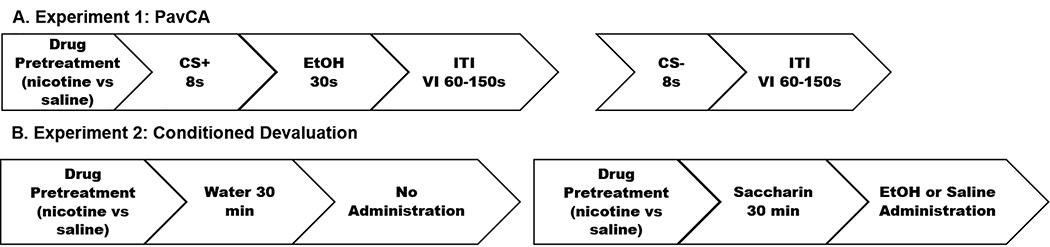

Fig. 1 |.

Diagram of the experimental design for experiment 1 & 2. (A). In experiment 1, Pavlovian conditioning sessions consisted of an 8-s extension of either the lever CS+ or CS-. The CS+ was followed by a 30-s extension of the ethanol US via a sipper bottle, while the CS- was not. An inter-variable interval between 60–150-s preceded the start of the next trial. There were 15 lever extensions per lever for a total of 30 trials per session. (B). In experiment 2, rats were administered nicotine or saline 30 min prior to testing. On non-conditioning days, water was available for 30 min, followed by nothing. On conditioning days, 0.1% saccharin was available for 30 min, immediately followed by i.p. injection of ethanol. This two-day pattern was repeated for 14 total days allowing for testing with 7 concentrations of ethanol in ascending order.

On the morning of each session, rats were weighed, injected with nicotine or saline, placed into plastic transfer containers (43.5 cm L × 20.3 cm W × 17.8 cm H) on a transfer cart for 15-min, and then moved to the testing room and placed into conditioning chambers. After a 2-min delay, the illumination of the house light signaled the start of the session. For this experiment, the conditioned stimulus (CS+) was an 8-s extension of one retractable lever, which was followed by delivery of the unconditioned stimulus (US), a sipper bottle containing 20% ethanol. The sipper bottle was deployed into the chamber for 30 s, and rats were allowed to freely drink from the sipper bottle for the entire 30 s before it was retracted. The extension of the other lever (CS-) was not followed by a deployment of the sipper bottle into the chamber. The CS+ and CS- levers were counter-balanced between subjects to either the left or right side of the chamber. Lever CS+ and lever CS- presentations occurred randomly on a VI 105 (60 – 150 s) schedule with 15 presentations per lever for a total of 30 presentations. Sessions lasted on average 54.5 min.

Measures

The number of lever/faceplate contacts, lever presses, and sipper bottle/faceplate contacts were recorded during lever and sipper bottle presentations for each session. Sign-tracking was defined as lever contacts or presses during lever CS+ extensions, while goal-tracking was measured by sipper bottle faceplate contacts during lever CS+ extensions. Note that, since the sipper itself was not extended until after the CS+, goal-tracking reflects only the faceplate contacts.

Experiment 2: Effect of nicotine on sensitivity to the aversive properties of ethanol in an augmented CTA paradigm

Training

Following acclimatization to the animal holding facility, rats were maintained on 23.5 h water deprivation. Rats were initially trained to consume their daily allotment of water in 30 min sessions in their home cage 30 min following a saline injection (1 ml/kg, s.c.). Once stable baseline intakes were reached, rats were assigned to one of four groups in a weight- and intake-balanced fashion: Sal-Sal (n=5); Nic-Sal (n=5); Sal-EtOH (n=7); Nic-EtOH (n=8) defined as either receiving pretreatment with nicotine or saline and then receiving either an ethanol or saline injection (unconditioned stimulus; US) paired with the flavor cue on conditioning days. Training continued for three more days during which rats in the two nicotine groups received nicotine injections (0.4 mg/kg, s.c.) in lieu of saline injections.

Testing

Immediately following training, rats were tested in an adaptation of the ethanol-induced CTA paradigm (Fig. 1B). Briefly, on the first day of testing, rats were injected with their assigned drug stimulus (saline or nicotine) 30 min prior to access to a 0.1% saccharin solution (conditioned stimulus; CS+) for 30 min in the home cage. At the end of saccharin drinking, rats were immediately injected i.p. with either ethanol or equivolume saline. The subsequent day of testing was identical with two critical exceptions: rats drank water (CS-) in the home cage following which all rats were injected with saline. This two day pattern was repeated for 14 days allowing for testing with 7 doses of ethanol (16% v/v delivered at doses of 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, 1.5, 1.8, 2.1, & 2.4 g/kg). Ethanol concentrations were tested in ascending order in all rats and saline injections in the unconditioned controls were matched for volume.

Measures

Saccharin and water intakes were assessed by weighing the individual bottles prior, and subsequent, to home cage drinking sessions. In order to determine the efficacy for a given dose of ethanol to condition avoidance of subsequent saccharin drinking sessions these data were converted to a devaluation score by dividing intake on a particular conditioning day by the initial, baseline intake. Curves were fit to these suppression scores and the ED50 was calculated using a three-parameter logistical function:

Where a is equal to asymptotic consumption, b is equal to the slope of the curve and c is the ED50, or the concentration at which one-half asymptotic consumption was seen. Curve fitting was conducted with Systat 12.

Data Analyses

Chronic intermittent access to ethanol

For the CIA data, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted on intake data that had been corrected for fluid loss. Differences in total fluid intake was analyzed with Exposure (ethanol, water) as the between groups factor and Ethanol Session (i.e. 1–14) as the within-groups factors. We also examined ethanol intake (g/kg/24 h; grams of ethanol consumed per kilogram of body weight over each 24-h Ethanol Session) and ethanol preference (%; ratio of grams of ethanol solution consumed to total grams of fluid consumed over each 24-h Ethanol Session) in ethanol-exposed rats across Ethanol Session. Significance was determined as p < .05 for this and all measures.

Ethanol Pavlovian conditioned approach

For Exp. 1, all variables were calculated by taking the average of the data across each 5-session week. Data from PavCA sessions were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA with Week (1–7) and CS (CS+, CS-) as within-groups factors, and Exposure (ethanol-exposed, unexposed) and Drug (nicotine, saline) as the between-groups factors. Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests were used to further examine significant main effects and interactions.

Ethanol Pavlovian conditioned avoidance

Intake suppression scores were analyzed with a repeated-measures ANOVA where Drug (nicotine or saline) and US Treatment (ethanol or saline) were between-subjects factors and Day (1–14) and CS (saccharin or water) were the within-subjects factors. The ED50 concentration in animals receiving ethanol as US were analyzed between nicotine- and saline-treated rats with an independent samples t-test. Significance was determined as p < 0.05 for this and all other measures. Planned comparisons between nicotine- and saline-treated rats were conducted independently for the ethanol-treated experimental group and saline-treated unconditioned control group.

Results

Experiment 1

Chronic intermittent access to ethanol

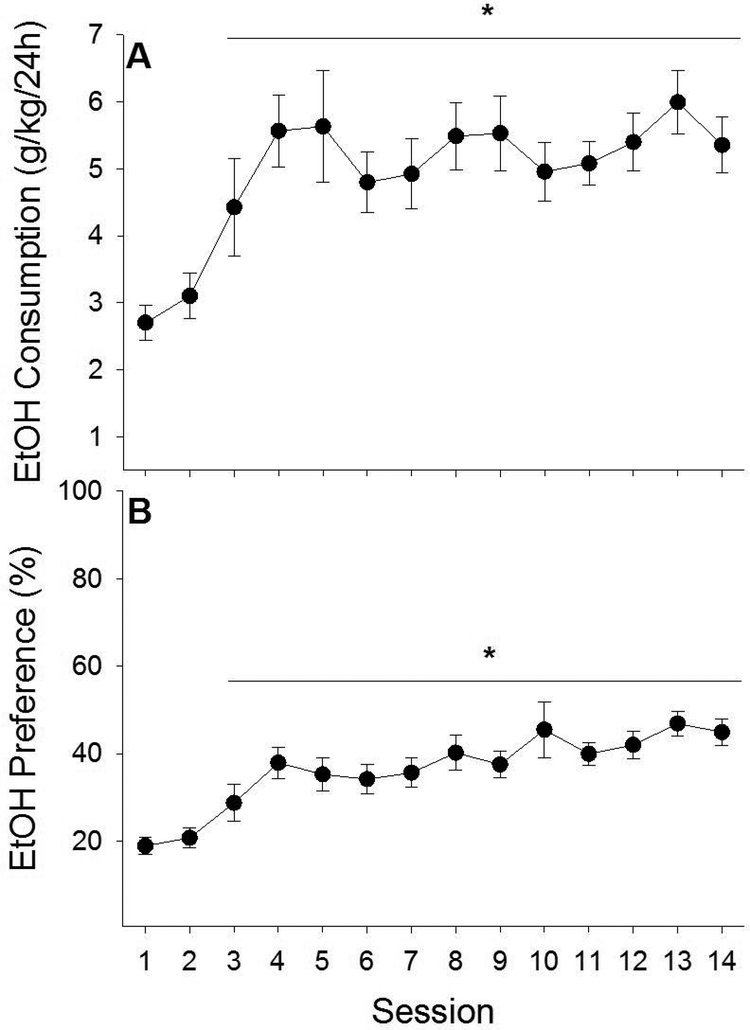

While total fluid intake decreased among all rats across ethanol drinking sessions, ethanol-exposed rats consumed more total fluid (water + ethanol) than unexposed rats (water only) (main effects of Exposure [F1,32 = 11.10, p < .01] and Ethanol Session [F13, 416 = 20.17, p < .001]). In addition, ethanol-exposed rats increased their ethanol intake and ethanol preference across ethanol drinking sessions (Fig. 2A & B; main effects of Ethanol Session on ethanol intake (g/kg/24 h) [F13, 208 = 5.81, p < .001] and ethanol preference (%) [F13, 208 = 8.79, p < .001]). Post-hoc analyses indicated that ethanol intake (p < .001) and ethanol preference (p < .001-.02) were significantly higher on sessions 3–14 relative to the first ethanol drinking session.

Fig. 2 |.

In experiment 1, ethanol-exposed male rats consumed more total fluid than ethanol-unexposed male rats and demonstrated increased ethanol intake and preference across ethanol sessions. Ethanol-exposed rats with access to two bottles separately containing water and ethanol (20% v/v) demonstrated increased ethanol intake (A) and preference (B) across ethanol sessions. Intakes and preferences observed across ethanol sessions 3–12 were significantly greater than those on session 1. Asterisk (*) designates significant post-hoc analyses (ps < 0.05).

Ethanol Pavlovian conditioned approach

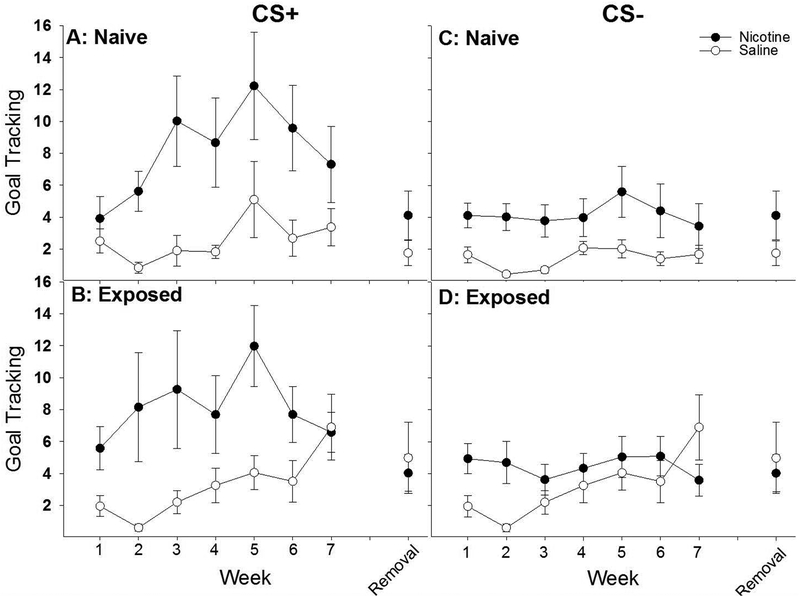

Sipper bottle faceplate contacts (“goal-tracking”)

All rats goal-tracked more to the CS+ than the CS- (Fig. 3: main effects of CS [F1, 30 = 24.58, p < .001], Week [F6, 180 = 3.92, p = .001], and CS × Week interaction [F6, 180 = 4.70, p < .001]), but the number of goal-tracking responses were significantly enhanced by nicotine treatment, as measured by sipper bottle faceplate contacts elicited by the CS+ and CS- (main effect of Drug [F1, 30 = 13.30, p < .001] as well as CS × Drug [F1, 30 = 7.01, p < .05] and CS × Drug × Week [F6, 180 = 2.33, p < .05] interactions). No main effect or interaction with Exposure was found. Post-hoc analyses of the CS × Drug × Week interaction indicated that nicotine-treated rats made significantly more sipper bottle faceplate contacts than saline-treated rats, regardless of previous ethanol exposure, during lever CS+ extensions across weeks 2–6 (Fig. 3 A & B: p ≤ .01). Additionally, nicotine-treated rats discriminated between the CS+ and CS- across weeks 2–7, while saline-treated rats only did so during weeks 5 and 7 (Fig. 3A). Thus, nicotine-treated rats discriminated more consistently between the CS+ and CS-, and nicotine specifically enhanced the goal-tracking response to the CS+ more than the goal-tracking response to the CS-. To ensure that the heightened goal-tracking response in nicotine-treated rats was not necessarily due to differences in rate of acquisition, we ran a separate ANOVA comparing the goal-tracking response between nicotine- and saline-treated rats during weeks 5–7, a time in which saline-treated rats had demonstrated statistically significant discrimination between the CS+ and CS-. This ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Drug (F1,30 = 6.90, p < 0.05) and a Drug × Week interaction (F2,60 = 6.19, p < 0.01). Thus, once all rats had effectively acquired the CS+ association, nicotine-treated rats displayed higher goal-tracking responses relative to saline-treated rats.

Fig. 3 |.

In experiment 1, nicotine significantly enhanced goal-tracking in response to an ethanol-associated cue relative to saline-treated male rats. Regardless of previous history with ethanol (naive [A] vs exposed [B]), nicotine enhanced the tendency to approach and interact with the reward delivery apparatus (‘goal-tracking’) during an 8 s lever extension (CS+) that immediately preceded delivery of a retractable bottle that contained 20% ethanol. This enhancement of goal‐tracking was largest in response to the CS+, though nicotine-treated rats approached the reward receptacle more than saline‐treated rats during the CS− as well (C and D). The enhancement of goal-tracking was lost when nicotine was removed, indicating that the behavioral effects were likely due to acute administration of nicotine.

Next, sipper bottle faceplate contacts elicited by the CS+ and CS- were analyzed separately. For contacts elicited by the CS+, nicotine enhanced goal-tracking relative to saline (Fig. 3A & B: main effects of Drug [F1, 30 = 11.92, p < .01], Week [F6, 180 = 4.85, p < .001] and a significant Drug × Week interaction [F6, 180 = 2.42, p < .05]). No main effect or interaction with Exposure was found. Post-hoc analyses of the Drug × Week interaction indicated that nicotine treatment enhanced sipper bottle faceplate contacts elicited by the CS+ relative to saline treatment across weeks 2–6 (p < .01). Furthermore, nicotine enhanced sipper bottle faceplate contacts across weeks 3–6 relative to week 1 (p < .05), while saline did not enhance sipper bottle faceplate contacts across any week relative to week 1, albeit there was a trend for an enhancement when comparing week 7 to week 1 (p = 0.06). For contacts elicited by the CS-, we again found no main or interactive effects of Exposure but there was a main effect of Drug that did not interact with Week indicating that nicotine tended to increase responding during the CS- period in general. To ensure that the effects of nicotine were greater for responding during the CS+ period, as was suggested by the significant CS × Drug × Week interaction from the omnibus ANOVA, we next subtracted the CS- responding from the CS+ responding and examined this difference-score in a separate ANOVA. Here, we again found a significant main effects of Drug [F(1,30) = 7.01, p < .05] and Week [F(6,180) = 4.70, p < .001] a significant Drug × Week [F(6,180) = 2.33, p < .05] interaction. Thus, nicotine treatment, relative to saline treatment, enhanced goal-tracking elicited by the CS+ more than to the CS-.

Lever contacts (“sign-tracking”)

All rats sign-tracked more during the CS+ than the CS-, as measured by lever contacts elicited by the CS+ and CS- (Fig. 4: main effects of CS [F1, 30 = 12.75 p = .001], Week [F6, 180 = 6.43 p < .001] and a significant CS × Week interaction [F6, 180= 3.17 p = .01]). Post-hoc analyses of the CS × Week interaction indicated that the CS+ elicited more lever contacts than the CS- across all weeks following week 1 (p < .001). No significant main effect or interactions with Exposure or Drug were found (Fig. 3B–C). Thus, all rats were able to discriminate which lever was predictive of the reward and, consequently, the CS+ elicited more sign-tracking than the CS-.

Fig. 4 |.

Nicotine did not significantly affect sign-tracking to an ethanol-associated cue in male rats. There was a trend for nicotine to enhance sign-tracking to the CS+ (A & B), but only in the rats previously exposed to ethanol in the CIA paradigm, although this effect failed to reach statistical significance. Further support for this trend is provided by the complete loss of a sign-tracking response upon the removal of acute nicotine administration (B). Neither nicotine, nor ethanol exposure, affected responding to the CS- (C & D).

When lever contacts elicited by the CS+ were analyzed separately (Fig. 4A & B), nicotine had no significant effect on sign-tracking conditioned responding relative to saline. Repeated-measures ANOVA examining the effects of Exposure and Drug on CS+ contacts during CS+ extensions across weeks 1–7 yielded no significant main effects or interactions with Exposure, Drug, or Week.

Ethanol consumption during conditioning

Examining the average total licks (Table 1) elicited to the 20% ethanol solution across the 7 week conditioning paradigm revealed a main effect of Week [F6,180 = 4.49, p < 0.001] and Week × Drug [F6,180 = 2.69, p < 0.05] and Week × Exposure [F6,180 = 4.58, p < 0.001] interactions. Post hoc analyses of the two interactions indicated that, as a whole, saline-treated rats consumed significantly more ethanol across Weeks 4–7, relative to their own consumption on Week 1, while nicotine treated rats tended to start consumption higher and remained relatively stable across testing. For the Week × Exposure interaction, non-exposed rats, as a whole, consumed significantly more ethanol across Weeks 2–7, relative to their own consumption on Week 1. Ethanol-exposed rats did not significantly alter their intake across the 7 week paradigm.

Table 1:

Average licks to 20% EtOH across the seven week discriminated approach paradigm

| Group | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtOH Exposed – Nicotine | 206 ± 35.2 | 240 ± 75.0 | 131.7 ± 21.8 | 123.7 ± 32.1 | 122.7 ± 26.4 | 189.7 ± 41.8 | 161.9 ± 40.4 |

| EtOH Exposed – Saline | 68.9 ± 9.7 | 118.1 ± 53.2 | 118.0 ± 60.0 | 161.2 ± 55.0 | 147.4 ± 52.8 | 114.6 ± 37.7 | 161.8 ± 61.5 |

| Non Exposed – Nicotine | 112.6 ± 6.9 | 201.0 ± 74.1 | 211.5 ± 65.2 | 211.5 ± 58.7 | 259.9 ± 90.3 | 316.4 ± 109.3 | 200.0 ± 60.9 |

| Non Exposed – Saline | 59.1 ± 13.3 | 95.6 ± 38.8 | 118.3 ± 38.4 | 200.1 ± 57.0 | 261.5 ± 71.2 | 241.5 ± 93.0 | 197.0 ± 48.2 |

Nicotine removal

Goal-tracking.

Removing nicotine treatment did not specifically alter goal-tracking elicited by the CS+ (Fig. 3A & B). While a repeated-measures ANOVA on sipper bottle faceplate contacts during the lever CS+ revealed a significant main effect of Week [F1, 30 = 11.52, p < .01], such that sipper bottle faceplate contacts in week 8 were significantly reduced relative to week 7 (p < .002; Fig. 4D), there were no significant main effects or interactions with Exposure or Drug. Thus, while nicotine treatment did significantly increase goal-tracking across weeks 1–7, removing nicotine during week 8 did not result in significantly reduced goal-tracking relative to week 7. This is lack of an effect could be driven by the already evident trend towards decreasing goal-tracking observed starting at week 6 in both naive and ethanol exposed nicotine-treated rats (Fig 4A & B, respectively). Nevertheless, there was no significant differences among groups in goal-tracking once nicotine was removed, suggesting that the significant differences in responding were due to acute actions of nicotine.

Sign-tracking.

Sign-tracking during nicotine removal (week 8) was compared to the last week of PavCA testing (week 7). In contrast to goal-tracking, removing nicotine treatment decreased sign-tracking elicited by the CS+ (Fig. 4A & B: interaction of Drug × Week [F1, 30 = 4.41, p < .05], and trends for a main effect of Week [F1, 30 = 3.85, p = .06] and an Exposure × Week interaction [F1, 30 = 3.17, p = .085]). No main effect of Exposure was found. Post-hoc analysis revealed that previously nicotine-treated rats significantly reduced CS+ contacts during week 8 relative to week 7 (p < .01; Fig. 4A), while saline-treated rats had no significant change in contacts across weeks. Thus, while nicotine treatment did not significantly increase sign-tracking across weeks 1–7, removing nicotine during week 8 resulted in reduced sign-tracking relative to week 7.

Experiment 2

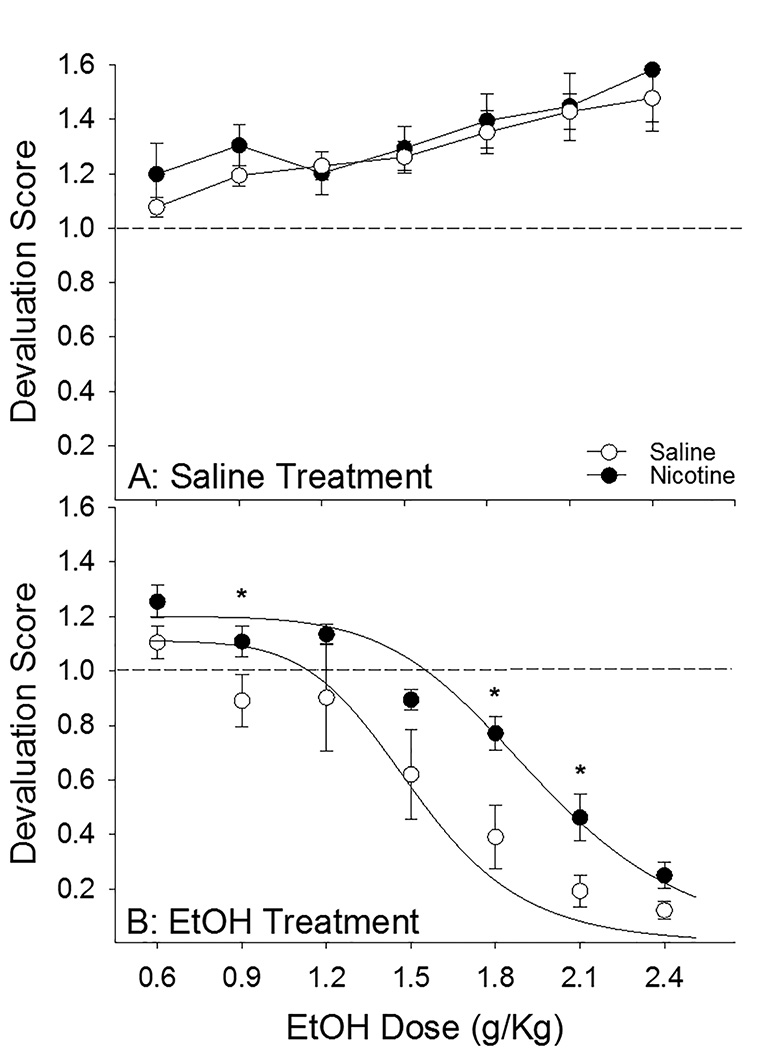

Regardless of drug treatment (nicotine or saline), rats receiving the flavor cue paired with increasing saline volume displayed a tendency to increase intake of saccharin across testing sessions while rats receiving the same flavor cue paired with increasing ethanol dose decreased their intake of the saccharin solution across days (Fig. 5A & B: main effects of Day [F6, 126 = 12.36, p < .001] and US [F1, 21 = 37.90, p < .001] and Day × US interaction [F6, 126 = 21.53, p < 0.001]) with no substantial change in the unpaired fluid consumption (i.e. water, data not shown; CS × Day × US interaction [F6, 126 = 38.94, p < .001]). Importantly, there was an effect of nicotine to reduce the devaluation conditioned by a given dose of ethanol (Fig. 5B: main effect of Drug [F1, 21 = 4.33, p = 0.05] and Drug × US interaction [F1, 21 = 6.50, p < 0.05]) with no effect on saccharin intake when paired with saline (Fig. 5A). Planned comparisons between saline- and nicotine-treated rats receiving the flavor cue paired with ethanol revealed that nicotine treated rats had significantly lower levels of devaluation following pairing with 0.9, 1.8, & 2.1 g/kg ethanol (ps < .05), with a trend for a difference at the 1.5 g/kg dose (p = .053), while saline- and nicotine-treated rats receiving the flavor cue paired with equivolume saline did not significantly differ at any point. Finally, when comparing the ED50, it was revealed that nicotine administration shifted the dose-response curve to the right (Fig. 6: t13 = 2.28, p < 0.05) indicating that nicotine-treated rats were less sensitive to the aversive conditioning properties of ethanol relative to saline-treated rats. The dose of ethanol that produced a 50% decrement in intake in nicotine-treated rats was ~2.0 g/kg while the dose producing an equivalent degree of devaluation in saline-treated rats was ~1.5 g/kg.

Fig. 5 |.

Nicotine reduced sensitivity to the devaluation induced passive administration of ethanol in male rats. A devaluation score of 1.0 indicates no change from baseline consumption of saccharin, any score above 1.0 indicates an increase in consumption while any score below 1.0 indicates a decrease. Nicotine administration had no effect on saccharin intake in saline-treated unconditioned controls (A). Conversely, nicotine diminished the degree of devaluation induced by increasing doses of ethanol (B). Nicotine-treated, relative to saline-treated, rats were significantly more accepting of saccharin following conditioning with 0.9, 1.8, & 2.1 g/kg ethanol, with a nonsignificant trend for increased acceptance at the 1.5 g/kg dose. In general, nicotine-treated rats were less sensitive to the devaluation induced by acute ethanol intoxication. * designates significant group difference (ps < .05).

Fig. 6 |.

Nicotine produced a significant rightward shift in the dose-response curve of ethanol-induced devaluation. Calculation of the ED50 of the curve from Fig 5B revealed that nicotine pretreatment resulted in a significant rightward shift in the dose-response curve indicating that nicotine-treated rats were less sensitive to the stimulus properties of ethanol that produce stimulus devaluation. The dose that produced a 50% decrement in saccharin intake was ~1.5 g/kg in saline-treated rats compared to ~2.0 g/kg in nicotine-treated rats. * designates significant group difference (p < .05)

Discussion

Summary

In these studies, we show that nicotine significantly impacts two contrasting ethanol-motivated behaviors in male rats. In a Pavlovian conditioned approach paradigm, nicotine facilitated approach elicited by an ethanol cue. However, this approach was directed towards the location of the ethanol reward (‘goal-tracking’), rather than towards the ethanol cue (‘sign-tracking’), and, further, we did not observe an obvious ‘switch’ from goal-tracking to sign-tracking over extended conditioning as reported by Srey et al. (2015). In addition, nicotine reduced the avoidance of a flavor cue paired with the aversive consequence of acute ethanol intoxication in a Pavlovian conditioned avoidance paradigm. More specifically, nicotine treatment resulted in a significant rightward shift in the dose-response curve indicating that acute nicotine administration reduced the sensitivity to the aversive physiological properties of concentrated ethanol, similar to what we have previously shown with morphine (Loney and Meyer, 2018).

Nicotine increased goal-tracking in response to an ethanol cue

Regardless of previous history of ethanol drinking, nicotine facilitated goal-tracking towards the ethanol reward following presentation of a lever-cue explicitly paired with ethanol (Fig. 3A & B). There was a trend for enhancement of sign-tracking, but only in rats that were experienced with ethanol. These data indicate that nicotine affects goal-tracking conditioned approach to an ethanol cue more strongly than sign-tracking, which is in contrast with studies of nicotine’s effects on cues that predict non-drug reinforcers (but see Stringfield et al., 2017). We had originally hypothesized that nicotine would enhance sign-tracking to an ethanol cue because nicotine generally increases conditioned approach elicited by a combined auditory and visual Pavlovian ethanol cue (Maddux and Chaudhri, 2017) and specifically increases sign-tracking to other non-drug reinforcers (Palmatier et al., 2013, Versaggi et al., 2016). Furthermore, ethanol cues have previously been shown to elicit sign-tracking after extended conditioning (Srey et al., 2015). However, in our hands, nicotine did not significantly enhance sign-tracking in male rats, and instead only affected goal-tracking. This may have been due to the technical features of our design. First, the mechanical noise emitted during the bottle insertion may have served as a CS that was more proximal to ethanol delivery than the lever-CS. Indeed, previous research has shown that cues more proximal to reward delivery serve as better conditioned reinforcers than distal cues (Holland, 1980, Meyer et al., 2014, Tindell et al., 2005). This may have promoted conditioned responding to the bottle insertion at the expense of responding to the lever insertion. Second, while rats have been shown to discriminate between ethanol predictive (CS+) and nonpredictive stimuli (Krank et al., 2008), it is possible that the task was too difficult for all rats to acquire the CS+ lever-ethanol association. Supporting this idea, only nicotine-treated rats consistently discriminated between extensions of the CS+ and CS- as measured by bottle contacts during lever extensions (Fig. 3A & B). This is in line with prior research demonstrating that nicotine most consistently increases task performance in cognitively unimpaired populations during challenging tasks (Mirza and Stolerman, 1998, Stolerman et al., 2000, Hahn et al., 2002), and, thus nicotine may have aided task acquisition here. Analyzing goal-tracking during weeks 5–7, once all groups had acquired discrimination between the CS+ and CS- continued to reveal significantly heightened responding in the nicotine-treated rats relative to saline-treated rats. Similarly, removal of nicotine resulted in similar responding among the groups, albeit goal-tracking was beginning to decrease in the nicotine-treated rats. Unfortunately, our experimental design does not allow us to explicitly dissociate effects that nicotine may be having on acquisition of conditioning responding as nicotine was administered from the start of the test.

Nicotine had marginal effects on sign-tracking

Nicotine treatment tended to promote sign‐tracking to the CS+ more than the CS−, although this effect was transient and not statistically significant (Fig. 4). Therefore, it may have been that nicotine’s effects on sign-tracking were obscured by the difficulty of the task. While we note that nicotine preferentially enhanced goal-tracking, relative to sign-tracking, in this study, there was some limited evidence for an effect of nicotine on sign-tracking in rats with a history of ethanol exposure (Fig. 4B). This coincides with the significant reduction in sign-tracking that occurred upon nicotine removal during week 8 (Fig. 4B). Ultimately, we did not find that ethanol cues uniformly promoted sign-tracking over extended conditioning as has been shown previously (Srey et al., 2015), although we did see a trend towards a decrease in goal-tracking that began around week 6. Interestingly, one other study looking at the effects of nicotine on PavCA elicited by a non-drug cue has also reported substantial increases in goal-tracking responses (Stringfield et al., 2017). Thus, nicotine may affect conditioned responding to both drug and non-drug cues by increasing approach towards an individual’s prepotent cue (either the cue or the goal), as has been shown with opioid drugs (DiFeliceantonio and Berridge, 2012) and therefore this form of conditioning may be highly susceptible to individual variation. Furthermore, we estimate that the rats were consuming ~0.5–0.6 g/kg of ethanol during the 1-h conditioning sessions. As we did not measure BECs, this is an estimation based on the recorded number of licks (Table 1) elicited during the US period. These are relatively low doses, and so it is possible that other factors besides the pharmacological properties of EtOH may have contributed to PavCA. Moreover, the relatively low consumption of EtOH during conditioning, particularly in the naïve animals, may partially explain the low levels of sign‐tracking behaviors. The development of sign-tracking towards ethanol-predictive cues may require higer doses of ethanol consumption, a conclusion supported by the finding that the only group that demonstrated notable sign-tracking responses was the nicotine-treated exposed rats which consumed the largest quantities of ethanol during the initial weeks of conditioning (Table 1).

Nicotine reduced sensitivity to devaluation induced by acute ethanol intoxication

We and others have previously shown that pre-exposure to nicotine blocks acquisition of ethanol-induced conditioned taste avoidance (Loney and Meyer, 2019, Kunin et al., 1999, Rinker et al., 2011, Bienkowski et al., 1998). Here, we demonstrate that nicotine is not simply blocking the ability to learn a CTA to ethanol-paired flavors, but rather that nicotine, relative to saline, reduces the sensitivity to a given dose of ethanol thus resulting in a significant rightward shift in the degree of devaluation conditioned by ethanol (Figs. 5B & 6). It should be noted that acquisition of CTA occurs over repeated conditioning trials and that increasing doses of ethanol overlap with repeated pairings in our experimental design. Regardless, these data are in line with previous reports that nicotine reduces the aversive physiological consequences of acute ethanol intoxication in rodents (Rinker et al., 2011, Taslim et al., 2011) as well as reports that smokers feel less intoxicated by a given dose of ethanol relative to nonsmokers (Madden et al., 2000). Nicotine had no effect on the consumption of saccharin in our unconditioned control rats (Fig. 5A) and, furthermore, our previous data revealed that nicotine had no effect on a LiCl‐induced CTA (Loney and Meyer, 2019) indicating that the effects of nicotine were specific to the EtOH dosing rather than a general effect on either taste processes or the ability to express a CTA. Lower doses of drugs that are readily self‐administered by animals can condition an avoidance response to slightly less reinforcing stimuli, such as saccharin, when the two stimuli are presented in sequence. This form of successive contrast has been referred to as the reward‐comparison hypothesis (Grigson, 2008). Given that our design employs saccharin as the conditioned stimulus, we cannot entirely rule out that the observed avoidance is, at least in part, mediated by the reinforcing properties of EtOH as opposed to its aversive qualities. Also, identical results were observed when sodium chloride (Loney et al., 2018) served as the conditioned stimulus, as well as with unsweetened Kool‐Aid® flavors (unpublished observations) that have no inherent reinforcing value to laboratory rats, therefore the avoidance is likely generated by the aversive properties of EtOH as opposed to its reinforcing qualities. Furthermore, low doses of ethanol (< 0.75 g/kg) have been shown to produce avoidance responses indicative of successive contrast while higher doses (~1.5 g/kg) produce avoidance responses that are more in line with aversion (Liu and Grigson, 2009). Here, we report the ED50 in saline-treated rats as 1.5 g/kg while the ED50 in nicotine-treated rats is 2.0 g/kg, doses that would objectively be on the higher end of the dose-response curve. We have previously demonstrated that our nicotine treatment regimen obscures the interoceptive cues resulting from passive administration of drugs of abuse (Loney and Meyer, 2018a). Drug taking is regulated by interoceptive effects and facilitated by drug-associated external cues. Any reduction in the sensitivity to these interoceptive cues may enhance the reliance on external cues to spur drug seeking similar to the way nicotine self-administration is dependent on predictive external cues (Caggiula et al., 2001). This is consistent with our current finding that nicotine enhances goal-directed alcohol seeking regardless of previous drinking history, while simultaneously diminishing the impact of the aversive post-ingestive qualities of ethanol.

A reduction in the impact of the aversive consequences of acute ethanol intoxication following nicotine administration may be sufficient to explain the enhancement of the conditioned approach towards stimuli predictive of ethanol delivery by nicotine, regardless of previous experience with ethanol, that we report here (Figs. 3 & 4). Specifically, by diminishing the impact of any aversive consequence of ethanol consumption, nicotine could be indirectly enhancing the reinforcing properties of ethanol consumption and thus engendering heightened approach to ethanol-predictive cues. These putative indirect effects would be in addition to the direct effects that nicotine has on the dopaminergic response to ethanol (Doyon et al., 2013), which likely independently drives increased motivational value of ethanol. One potentially important consideration is that we did not measure blood ethanol concentration (BEC) following i.p. injection of ethanol as a function of nicotine treatment; although a previous study has demonstrated that nicotine does not impact BEC following i.p. ethanol administration, rather only during intragastric administration of ethanol (Parnell et al., 2006). Regardless of mechanism or order of effects, drinking despite adverse consequences is a hallmark of alcohol-use disorders (AUDs; Tiffany and Conklin, 2000, Naqvi and Bechara, 2010, Seif et al., 2013) and we show that nicotine diminshes the aversive consequences of ethanol consumption as evidenced by a significant reduction in the devaluation induced by acute ethanol intoxication. Additional studies are currently being conducted to elucidate the paramaters of this effect within this paradigm and other Pavlovian conditioning paradigms aimed at examining the aversive interoceptive qualities of ethanol including, but not limited to, conditioned place avoidance (CPA). We have previously demonstrated a lack of an effect of nicotine on ethanol-induced CPA (Loney et al., 2018), though within that study the time-course from nicotine administration to place conditioning was much longer and therefore nicotine may have been less effective. In addition, it is currently unknown what, if any, affect that the modulation of cue-reactivity by nicotine as reported here has on operant ethanol self-administration, particularly the development of habitual alcohol seeking that becomes resistent to devaluation (Corbit et al., 2012; Seif et al., 2013).

Nicotine simultaneously produces a high-apporach, low-avoidance phenotype

Extrinsic and intrinsic cues paired with the reinforcing properties of alcohol can acquire motivational relevance and drive alcohol seeking, thus increasing the likelihood of relapse (Jupp et al., 2011, Hay et al., 2013, Katner et al., 1999, Cannady et al., 2013). Conversely, cues paired with the aversive physiological properties of alcohol can also acquire motivational relevance and drive active avoidance of alcohol consumption (Liu et al., 2009, Kiefer and Morrow, 1991, Sheth et al., 2017, Verendeev and Riley, 2013, Seif et al., 2013). Clinical models of cue-induced alcohol craving demonstrate that reactivity to reinforcing and aversive ethanol cues independently contribute to the motivational drive to consume ethanol (Schlauch et al., 2015, Breiner et al., 1999). Furthermore, a high-approach, low-avoidance phenotype is associated with heightened ethanol consumption and an intractable attitude towards AUD treatment (Hollett et al., 2017, Stritzke et al., 2004, Schlauch et al., 2015, Sharbanee et al., 2014). Here, we demonstrate that acute nicotine treatment, prior to ethanol administration, produces a high-approach, low-avoidance phenotype even in ethanol-naïve male subjects (Figs. 3 & 4; Fig. 5B). As result, nicotine may be enhancing development and maintenance of, and subsequent relapse to, AUDs through enhancing the motivational drive triggered by alcohol-associated cues and simultaneously diminishing the impact of the aversive physiological properties of overconsumption. We, and others, have previously demonstrated that female rats are more sensitive to both the reinforcing properties of nicotine (Chaudhri et al., 2005) and the diminished avoidance of ethanol-paired cues induced by acute nicotine administration (Loney and Meyer, 2019). Therefore, future studies specifically designed to elucidate mechanisms contributing to enhanced sensitivity to nicotine in females and what contribution this may have on alcoholism liability in women are called for as these studies were not explicitly designed, nor powered to elucidate the effects of sex on responding to nicotine. Regardless, these data provide further support for smoking cessation as an important first step in successful treatment of AUDs.

Funding:

This research was supported by a grant from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA024112).

References

- Bienkowski P, Piasecki J, Koros E, Stefanski R, Kostowski W (1998) Studies on the role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the discriminative and aversive stimulus properties of ethanol in the rat. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 8:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bito-Onon JJ, Simms JA, Chatterjee S, Holgate J, Bartlett SE (2011) Varenicline, a partial agonist at neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, reduces nicotine-induced increases in 20% ethanol operant self-administration in Sprague-Dawley rats. Addict Biol 16:440–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiner MJ, Stritzke WG, Lang AR (1999) Approaching avoidance. A step essential to the understanding of craving. Alcohol Res Health 23:197–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF (2001) Cue dependency of nicotine self-administration and smoking. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior 70:515–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannady R, Fisher KR, Durant B, Besheer J, Hodge CW (2013) Enhanced AMPA receptor activity increases operant alcohol self-administration and cue-induced reinstatement. Addict Biol 18:54–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Booth S, Gharib MA, Craven LA, Allen SS, Sved AF, Perkins KA (2005) Sex differences in the contribution of nicotine and nonpharmacological stimuli to nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology 180:258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit LH, Janak PH (2007) Ethanol-associated cues produce general pavlovian-instrumental transfer. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 31:766–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit LH, Nie H, Janak PH (2012) Habitual alcohol seeking: time course and the contribution of subregions of the dorsal striatum. Biol Psychiatry 72:389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFeliceantonio AG, Berridge KC (2012) Which cue to ‘want’? Opioid stimulation of central amygdala makes goal-trackers show stronger goal-tracking, just as sign-trackers show stronger sign-tracking. Behav Brain Res 230:399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon WM, Thomas AM, Ostroumov A, Dong Y, Dani JA (2013) Potential substrates for nicotine and alcohol interactions: a focus on the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. Biochemical pharmacology 86:1181–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhofel S (2006) An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res Health 29:162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorenza AM, Shnitko TA, Sullivan KM, Vemuru SR, Gomez AA, Esaki JY, Boettiger CA, Da Cunha C, Robinson DL (2018) Ethanol Exposure History and Alcoholic Reward Differentially Alter Dopamine Release in the Nucleus Accumbens to a Reward-Predictive Cue. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 42:1051–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Akil H, Robinson TE (2009) Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to reward-related cues: Implications for addiction. Neuropharmacology 56 Suppl 1:139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Robinson TE, Clark JJ, Clinton SM, Watson SJ, Seeman P, Phillips PE, Akil H (2010) An animal model of genetic vulnerability to behavioral disinhibition and responsiveness to reward-related cues: implications for addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 35:388–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusser SM, Wrase J, Klein S, Hermann D, Smolka MN, Ruf M, Weber-Fahr W, Flor H, Mann K, Braus DF, Heinz A (2004) Cue-induced activation of the striatum and medial prefrontal cortex is associated with subsequent relapse in abstinent alcoholics. Psychopharmacology 175:296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn B, Shoaib M, Stolerman IP (2002) Nicotine-induced enhancement of attention in the five-choice serial reaction time task: the influence of task demands. Psychopharmacology 162:129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay RA, Jennings JH, Zitzman DL, Hodge CW, Robinson DL (2013) Specific and nonspecific effects of naltrexone on goal-directed and habitual models of alcohol seeking and drinking. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 37:1100–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC (1980) CS-US interval as a determinant of the form of Pavlovian appetitive conditioned responses. Journal of experimental psychology. Animal behavior processes 6:155–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollett RC, Stritzke WGK, Edgeworth P, Weinborn M (2017) Changes in the Relative Balance of Approach and Avoidance Inclinations to Use Alcohol Following Cue Exposure Vary in Low and High Risk Drinkers. Frontiers in psychology 8:645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp B, Krstew E, Dezsi G, Lawrence AJ (2011) Discrete cue-conditioned alcohol-seeking after protracted abstinence: pattern of neural activation and involvement of orexin(1) receptors. British journal of pharmacology 162:880–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katner SN, Magalong JG, Weiss F (1999) Reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior by drug-associated discriminative stimuli after prolonged extinction in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 20:471–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer SW, Morrow NS (1991) Odor cue mediation of alcohol aversion learning in rats lacking gustatory neocortex. Behavioral neuroscience 105:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krank MD, O’Neill S, Squarey K, Jacob J (2008) Goal- and signal-directed incentive: conditioned approach, seeking, and consumption established with unsweetened alcohol in rats. Psychopharmacology 196:397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin D, Smith BR, Amit Z (1999) Nicotine and ethanol interaction on conditioned taste aversions induced by both drugs. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior 62:215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Lo S, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Marinelli PW, Funk D (2010) Coadministration of intravenous nicotine and oral alcohol in rats. Psychopharmacology 208:475–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Wang A, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y (2003) Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration and reinstates alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology 168:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Showalter J, Grigson PS (2009) Ethanol-induced conditioned taste avoidance: reward or aversion? Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 33:522–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney GC, Meyer PJ (2018a) Brief Exposures to the Taste of Ethanol (EtOH) and Quinine Promote Subsequent Acceptance of EtOH in a Paradigm that Minimizes Postingestive Consequences. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 42:589–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney GC, Meyer PJ (2019) Nicotine pre-treatment reduces sensitivity to the interoceptive stimulus effects of commonly abused drugs as assessed with taste conditioning paradigms Drug Alcohol Depend January 1; 194:341–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney GC, Pautassi RM, Kapadia D, Meyer PJ (2018) Nicotine affects ethanol-conditioned taste, but not place, aversion in a simultaneous conditioning procedure. Alcohol 71:47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Martin NG, Heath AC (2000) Smoking and the genetic contribution to alcohol-dependence risk. Alcohol Res Health 24:209–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddux JN, Chaudhri N (2017) Nicotine-induced enhancement of Pavlovian alcohol-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology 234:727–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer PJ, Ma ST, Robinson TE (2012) A cocaine cue is more preferred and evokes more frequency-modulated 50-kHz ultrasonic vocalizations in rats prone to attribute incentive salience to a food cue. Psychopharmacology 219:999–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer PJ, Cogan ES, Robinson TE (2014) The form of a conditioned stimulus can influence the degree to which it acquires incentive motivational properties. PLoS One 9:e98163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton AL, Everitt BJ (2010) The psychological and neurochemical mechanisms of drug memory reconsolidation: implications for the treatment of addiction. Eur J Neurosci 31:2308–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza NR, Stolerman IP (1998) Nicotine enhances sustained attention in the rat under specific task conditions. Psychopharmacology 138:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi NH, Bechara A (2010) The insula and drug addiction: an interoceptive view of pleasure, urges, and decision-making. Brain Struct Funct 214:435–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmatier MI, Marks KR, Jones SA, Freeman KS, Wissman KM, Sheppard AB (2013) The effect of nicotine on sign-tracking and goal-tracking in a Pavlovian conditioned approach paradigm in rats. Psychopharmacology 226:247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnell SE, West JR, Chen WJ (2006) Nicotine decreases blood alcohol concentrations in adult rats: a phenomenon potentially related to gastric function. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 30:1408–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker JA, Hutchison MA, Chen SA, Thorsell A, Heilig M, Riley AL (2011) Exposure to nicotine during periadolescence or early adulthood alters aversive and physiological effects induced by ethanol. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior 99:7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC (1993) The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 18:247–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Yager LM, Cogan ES, Saunders BT (2014) On the motivational properties of reward cues: Individual differences. Neuropharmacology 76 Pt B:450–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BT, Robinson TE (2010) A cocaine cue acts as an incentive stimulus in some but not others: implications for addiction. Biol Psychiatry 67:730–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlauch RC, Rice SL, Connors GJ, Lang AR (2015) Ambivalence Model of Craving: A Latent Profile Analysis of Cue-Elicited Alcohol Craving in an Inpatient Clinical Sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 76:764–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seif T, Chang SJ, Simms JA, Gibb SL, Dadgar J, Chen BT, Harvey BK, Ron D, Messing RO, Bonci A, Hopf FW (2013) Cortical activation of accumbens hyperpolarization-active NMDARs mediates aversion-resistant alcohol intake. Nat Neurosci 16:1094–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharbanee JM, Hu L, Stritzke WG, Wiers RW, Rinck M, MacLeod C (2014) The effect of approach/avoidance training on alcohol consumption is mediated by change in alcohol action tendency. PLoS One 9:e85855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth C, Furlong TM, Keefe KA, Taha SA (2017) The lateral hypothalamus to lateral habenula projection, but not the ventral pallidum to lateral habenula projection, regulates voluntary ethanol consumption. Behav Brain Res 328:195–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms JA, Steensland P, Medina B, Abernathy KE, Chandler LJ, Wise R, Bartlett SE (2008) Intermittent access to 20% ethanol induces high ethanol consumption in Long-Evans and Wistar rats. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 32:1816–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srey CS, Maddux JM, Chaudhri N (2015) The attribution of incentive salience to Pavlovian alcohol cues: a shift from goal-tracking to sign-tracking. Front Behav Neurosci 9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman IP, Mirza NR, Hahn B, Shoaib M (2000) Nicotine in an animal model of attention. European journal of pharmacology 393:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringfield SJ, Palmatier MI, Boettiger CA, Robinson DL (2017) Orbitofrontal participation in sign- and goal-tracking conditioned responses: Effects of nicotine. Neuropharmacology 116:208–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke WG, Breiner MJ, Curtin JJ, Lang AR (2004) Assessment of substance cue reactivity: advances in reliability, specificity, and validity. Psychol Addict Behav 18:148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taslim N, Soderstrom K, Dar MS (2011) Role of mouse cerebellar nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) alpha(4)beta(2)- and alpha(7) subtypes in the behavioral cross-tolerance between nicotine and ethanol-induced ataxia. Behav Brain Res 217:282–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Conklin CA (2000) A cognitive processing model of alcohol craving and compulsive alcohol use. Addiction 95:S145–S153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindell AJ, Berridge KC, Zhang J, Pecina S, Aldridge JW (2005) Ventral pallidal neurons code incentive motivation: amplification by mesolimbic sensitization and amphetamine. Eur J Neurosci 22:2617–2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomie A, Sharma N (2013) Pavlovian sign-tracking model of alcohol abuse. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 6:201–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verendeev A, Riley AL (2011) Relationship between the rewarding and aversive effects of morphine and amphetamine in individual subjects. Learn Behav 39:399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verendeev A, Riley AL (2013) The role of the aversive effects of drugs in self-administration: assessing the balance of reward and aversion in drug-taking behavior. Behavioural pharmacology 24:363–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versaggi CL, King CP, Meyer PJ (2016) The tendency to sign-track predicts cue-induced reinstatement during nicotine self-administration, and is enhanced by nicotine but not ethanol. Psychopharmacology 233:2985–2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Goodwin RD (2017a) Cigarette smoking quit rates among adults with and without alcohol use disorders and heavy alcohol use, 2002–2015: A representative sample of the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend 180:204–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Platt J, Esan H, Galea S, Erlich D, Goodwin RD (2017b) Cigarette Smoking Is Associated With Increased Risk of Substance Use Disorder Relapse: A Nationally Representative, Prospective Longitudinal Investigation. J Clin Psychiatry 78:e152–e160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Rinck M, Dictus M, van den Wildenberg E (2009) Relatively strong automatic appetitive action-tendencies in male carriers of the OPRM1 G-allele. Genes Brain Behav 8:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]