Abstract

Background

This population‐based cohort study aimed to evaluate occurrence of low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) and correlate this to health‐related quality of life in patients who had undergone segmental colonic resection for colonic cancer in the Stockholm–Gotland region. The hypothesis was that there is a difference in occurrence of LARS depending on whether a right‐ or a left‐sided resection was performed.

Methods

Patients who underwent segmental colonic resection for colonic cancer stages I–III in the Stockholm–Gotland region in 2013–2015 received EORTC QLQ‐C30, QLQ‐CR29 and LARS score questionnaires 1 year after surgery. Clinical patient and tumour data were collected from the Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry. Patient‐reported outcome measures were analysed in relation to type of colonic resection.

Results

Questionnaires were sent to 866 patients and complete responses were provided by 517 (59·7 per cent). After right‐sided resection 20·6 per cent reported major LARS. After left‐sided resection the proportion with major LARS was 15·6 per cent. The odds ratio (OR) for major LARS after right‐sided resection was 1·45 (95 per cent c.i. 1·02 to 2·06; P = 0·037) compared with left‐sided resection. After adjustment for age and sex, an increase in the risk of major LARS after right‐ versus left‐sided resection remained (OR 1·48, 1·03 to 2·13; P = 0·035). Major LARS correlated with impaired quality of life.

Conclusion

Major LARS was more frequent after right‐sided than following left‐sided colonic resection. Major LARS reflected impaired quality of life.

Introduction

The number of long‐term survivors after treatment for colorectal cancer is increasing due to a rising incidence of the disease along with better chemotherapy, refined radiotherapy and advances in surgical technique. The benefit in oncological outcome may, however, be at the risk of adverse treatment‐related effects on functional outcomes and negative impact on quality of life1 2.

The National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden demands that population‐based nationwide registries include patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) as well as clinical and survival data. Since 2013, validated questionnaires to assess PROMs have been sent to patients treated for colorectal cancer in the Stockholm–Gotland region, an area with 2 million inhabitants and about 1000 patients annually with a new diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Initially the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core (EORTC QLQ‐C30) and Colorectal Module (QLQ‐CR29) were used3 4. Later, a questionnaire assessing low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) score was added to the regular request 1 year after surgery to all living patients treated for colorectal cancer5.

LARS consists of a number of symptoms such as leakage of stool or gas, clustering of stools, frequent bowel movements, urgency and evacuation problems. Previously, a high incidence of LARS symptoms has been shown in patients treated for rectal cancer6. These symptoms were related to inferior outcomes for several quality of life (QoL) items assessed by EORTC QLQ‐C30 and ‐CR297. Loss of reservoir function of the rectum, denervation of the neorectum and autonomic nerve injuries of the pelvis are potential pathophysiological mechanisms related to LARS symptoms in patients treated for rectal cancer2. The effects of segmental colonic denervation and resection of the ileocaecal valve on LARS symptoms in patients treated for colonic cancer have not been studied.

The aim of the present cohort study was to assess LARS symptoms in patients treated for colonic cancer with right‐ versus left‐sided colectomy and their effect on QoL.

Methods

Study design

This was a population‐based cohort study with type of colonic resection for colonic cancer (right‐ versus left‐sided) as exposure. The outcomes were bowel function and QoL, assessed by validated questionnaires. The hypothesis was that there would be a difference in outcome regarding bowel function between patients treated with right‐sided and those treated with left‐sided colectomy. The study was approved by the Karolinska Institutet regional ethics committee.

Setting and participants

All patients who had surgical resection of UICC colorectal cancer stages I–III between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2015 in the Stockholm–Gotland region and who were alive 1 year after surgery were eligible. Exclusion criteria were rectal cancer (adenocarcinoma within 15 cm of the anal verge), segmental resection of transverse colon, total colectomy, Hartmann procedure or appendicectomy alone. Patients with a stoma present 1 year after surgery and patients who did not receive the LARS score questionnaire with the regular request were also excluded.

From 1 January 2013, the Swedish versions of EORTC QLQ‐C30 and ‐CR29 were sent to all patients alive 1 year after surgery. The Swedish version of the LARS score questionnaire was added after 1 September 20138. Patients could choose to answer on paper or complete a web‐based questionnaire. One reminder was sent to non‐responders within 4 weeks.

Data sources

Data regarding epidemiology, staging, treatment and follow‐up were retrieved from the Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry (SCRCR), which includes data on all patients diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the colon in Sweden. National coverage in the SCRCR exceeds 98 per cent9.

Colon was defined as the large bowel 15 cm above the anal verge. Tumour locations were defined as appendix, caecum, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, splenic flexure, descending colon and sigmoid colon, as reported by the surgeon. Resection of the ileocaecal region or right colon was classified as right‐sided colectomy, and resection of the left colon or sigmoid was classified as left‐sided resection.

Variables

The outcomes were relevant aspects of QoL in patients with cancer (EORTC QLQ‐C30), specific aspects of QoL in patients with colorectal cancer (EORTC QLQ‐CR29) and signs of anterior resection syndrome (LARS score). These are validated questionnaires, available in Swedish8. All three questionnaires were evaluated according to available scoring manuals10. A difference of 10 points in EORTC scores was considered clinically important. The total LARS score ranges from 0 to 42 points and patients were classified as having no LARS (0–20 points), minor LARS (21–29 points) or major LARS (30–42 points).

Statistical analysis

Study data were analysed with Stata® version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Groups were compared with non‐parametric (Wilcoxon rank sum and Kruskal–Wallis) and Fisher's exact tests as appropriate. Ordinal logistic regression models were used to assess the effect of co‐variables on LARS scores registered in the three categories (no, minor or major LARS). Proportional odds assumptions were assessed with approximate likelihood ratio and Brant tests. The co‐variables shown in Table 1 were considered for the multivariable regression model. Owing to age‐ and sex‐related differences in anal function, age (categorized on interquartiles) and sex were included in the final multivariable regression model. The confounding effect of co‐variables was assessed and considered important if the effect of right‐ versus left‐sided colectomy on the LARS score was changed by more than 10 per cent. Statistically significant interactions were not identified. P < 0·050 was considered significant.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who had a colectomy and a complete response to questionnaires

| Right‐sided colectomy (n = 287) | Left‐sided colectomy (n = 230) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 74 (33–95) | 69 (37–91) | < 0·001‡ |

| Sex | 0·001 | ||

| F | 154 (53·7) | 90 (39·1) | |

| M | 133 (46·3) | 140 (60·9) | |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 26 | 25 | 0·502‡ |

| ASA classification | < 0·001 | ||

| I | 30 (10·6) | 39 (17·0) | |

| II | 126 (44·5) | 128 (55·7) | |

| III–IV | 127 (44·9) | 63 (27·4) | |

| Missing | 4 | 0 | |

| Emergency resection | 16 (5·6) | 8 (3·5) | 0·298 |

| Laparoscopic resection | 88 (30·7) | 93 (40·4) | 0·078 |

| Adverse events related to surgery | 32 (11·1) | 28 (12·2) | 0·783 |

| Length of hospital stay (days)* | 5 | 6 | 0·927‡ |

| TNM stage | 0·65 | ||

| I | 59 (20·6) | 40 (17·7) | |

| II | 136 (47·4) | 107 (47·3) | |

| III | 92 (32·1) | 79 (35·0) | |

| Missing | 0 | 4 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 64 (22·3) | 75 (32·6) | 0·009 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range).

Fisher's exact test, except

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Results

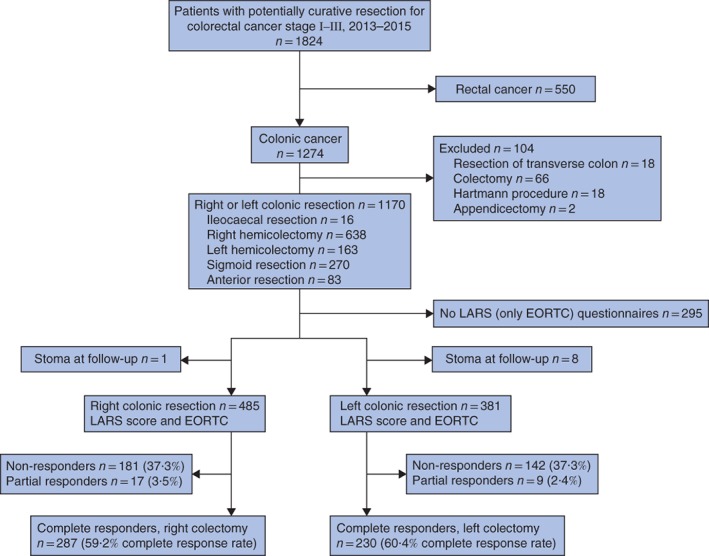

Between 2013 and 2015, 1170 patients had segmental colonic resection for colonic cancer in the Stockholm–Gotland region (Fig. 1). Requests did not include the LARS score in 295 patients, so complete requests were distributed to a total of 875 patients treated with right‐ or left‐sided colectomy. After exclusion of non‐responders or partial responders and patients with a stoma 1 year after surgery, 287 patients treated by right‐sided colectomy and 230 patients treated by left‐sided colectomy were included in the analysis. The frequency of complete responders to the three questionnaires was 59·7 per cent (517 of 866 patients).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study cohort in the Stockholm–Gotland region. LARS, low anterior resection syndrome.

Descriptive data

Right‐sided colectomy was more common in women (53·7 per cent) and left‐sided resection was more common in men (60·9 per cent) (P = 0·001) (Table 1). Median age was higher in the group undergoing right‐sided colectomy (74 years versus 69 years for left‐sided colectomy; P < 0·001). The proportion with ASA grade III–IV was higher for right‐sided colectomy (44·9 versus 27·4 per cent respectively; P < 0·001). Adjuvant chemotherapy was less common after right‐sided colectomy (22·3 versus 32·7 per cent; P = 0·009). The groups did not differ in terms of BMI, proportion of emergency resections, adverse events related to surgery, length of hospital stay, histopathological TNM stage or proportion of minimally invasive procedures.

Comparison between questionnaire responders and non‐ or partial responders showed no statistically significant differences regarding age, BMI, ASA grade, adverse events related to surgery, length of hospital stay, histopathological TNM stage, adjuvant chemotherapy or proportion of minimally invasive procedures (data not shown). Complete questionnaire response was more common for men than for women (52·8 versus 47·2 per cent respectively; P = 0·032), and non‐ or partial responders had more emergency resections than complete responders (11·7 versus 4·6 per cent respectively; P < 0·001).

Low anterior resection syndrome scores

The median total LARS score was comparable 1 year after right‐ or left‐sided colectomy (16 versus 15 points respectively; P = 0·212) (Table 2). The proportions of minor LARS (22·0 versus 17·8 per cent) and major LARS (20·6 versus 15·7 per cent) were higher after right‐sided than after left‐sided colectomy, although not statistically significantly so (P = 0·111). Accidental leakage of liquid stool (P = 0·026) and urgency at least once a week (P = 0·050) were more common after right‐sided colectomy. Incontinence to gas tended to be more frequent after left‐sided colectomy (P = 0·090); number of bowel movements and fragmented defaecation were similar in the two groups. The proportion of women with major LARS was 22·7 per cent after right‐sided versus 20 per cent after left‐sided colectomy (P = 0·828). The respective proportions in men were 18·0 and 12·9 per cent (P = 0·145).

Table 2.

Low anterior resection syndrome score 1 year after right‐ versus left‐sided colectomy

| Right‐sided colectomy (n = 287) | Left‐sided colectomy (n = 230) | P † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LARS | ||||

| Total LARS score* | 16 (0–42) | 15 (0–41) | 0·212‡ | |

| Overall | 0·111 | |||

| No LARS | 165 (57·5) | 153 (66·5) | ||

| Minor LARS | 63 (22·0) | 41 (17·8) | ||

| Major LARS | 59 (20·6) | 36 (15·7) | ||

| Women | n = 154 | n = 90 | 0·828 | |

| No LARS | 86 (55·8) | 54 (60) | ||

| Minor LARS | 33 (21·4) | 18 (20) | ||

| Major LARS | 35 (22·7) | 18 (20) | ||

| Men | n = 133 | n = 140 | 0·145 | |

| No LARS | 79 (59·4) | 99 (70·7) | ||

| Minor LARS | 30 (22·6) | 23 (16·4) | ||

| Major LARS | 24 (18·0) | 18 (12·9) | ||

| LARS score questions | Score | |||

| Do you ever have occasions when you cannot control your flatus (wind)? | 0·090 | |||

| No, never | 0 | 135 (47·0) | 88 (38·3) | |

| Yes, less than once per week | 4 | 84 (29·3) | 71 (30·9) | |

| Yes, at least once per week | 7 | 68 (23·7) | 71 (30·9) | |

| Do you ever have any accidental leakage of liquid stool? | 0·026 | |||

| No, never | 0 | 175 (61·0) | 162 (70·4) | |

| Yes, less than once per week | 3 | 14 (4·9) | 14 (6·1) | |

| Yes, at least once per week | 3 | 98 (34·1) | 54 (23·5) | |

| How often do you open your bowels? | 0·470 | |||

| More than 7 times a day (24 h) | 4 | 2 (0·7) | 1 (0·4) | |

| 4–7 times a day (24 h) | 2 | 25 (8·7) | 19 (8·3) | |

| 1–3 times a day (24 h) | 0 | 187 (65·2) | 164 (71·3) | |

| Less than once a day (24 h) | 5 | 73 (25·4) | 46 (20·0) | |

| Do you ever have to open your bowels again within 1 h of the last bowel opening? | 0·717 | |||

| No, never | 0 | 134 (46·7) | 109 (47·4) | |

| Yes, less than once per week | 9 | 99 (34·5) | 84 (36·5) | |

| Yes, at least once per week | 11 | 54 (18·8) | 37 (16·1) | |

| Do you ever have such a strong urge to open your bowels that you have to rush to the toilet? | 0·050 | |||

| No, never | 0 | 138 (48·1) | 132 (57·4) | |

| Yes, less than once per week | 11 | 103 (35·9) | 75 (32·6) | |

| Yes, at least once per week | 16 | 46 (16·0) | 23 (10·0) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range). LARS, low anterior resection syndrome.

Fisher's exact test, except

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Univariable ordinal logistic analysis with the three categories of LARS score as outcome showed that segment of resected colon and sex were significantly associated with LARS symptoms (Table 3). The proportional odds ratio (OR) was 1·45 (95 per cent c.i. 1·02 to 2·06; P = 0·037) for LARS after right‐ versus left‐sided colectomy, and 0·70 (0·50 to 0·99; P = 0·046) for men versus women.

Table 3.

Proportional odds ratios derived from ordinal logistic regression models with three categories of low anterior resection syndrome score as outcome

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | P | Odds ratio | P | |

| Segment of resected colon | ||||

| Left | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Right | 1·45 (1·02, 2·06) | 0·037 | 1·48 (1·03, 2·13) | 0·035 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 65 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| 65–72 | 1·26 (0·78, 2·04) | 0·346 | 1·24 (0·76, 2·01) | 0·391 |

| 72·1–80 | 0·76 (0·46, 1·25) | 0·282 | 0·71 (0·43, 1·18) | 0·192 |

| > 80 | 1·00 (0·60, 1·67) | 0·996 | 0·86 (0·51, 1·45) | 0·587 |

| Sex | ||||

| F | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| M | 0·70 (0·50, 0·99) | 0·046 | 0·73 (0·52, 1·05) | 0·094 |

| ASA grade | ||||

| I | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| II | 0·80 (0·47, 1·36) | 0·404 | ||

| III–IV | 1·30 (0·76, 2·24) | 0·334 | ||

| Operation | ||||

| Elective | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Emergency | 1·48 (0·69, 3·17) | 0·313 | ||

| Laparoscopic resection | ||||

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 1·09 (0·76, 1·58) | 0·635 | ||

| Intraoperative bleeding | 1·00 (0·99, 1·00) | 0·211 | ||

| BMI | 1·03 (0·99, 1·07) | 0·089 | ||

| Adverse events related to surgery | ||||

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 1·37 (0·81, 2·31) | 0·235 | ||

| Length of hospital stay | 1·03 (0·99, 1·07) | 0·061 | ||

| TNM stage | ||||

| I | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| II | 0·59 (0·38, 0·92) | 0·019 | ||

| III | 0·59 (0·36, 0·95) | 0·029 | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 1·07 (0·72, 1·57) | 0·739 | ||

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Age, BMI, ASA grade, emergency resection, adverse events related to surgery, length of hospital stay, pathological TNM stage, minimally invasive procedure and adjuvant chemotherapy were not related to LARS 1 year after surgery. The confounding effect of the predictors listed above did not exceed 10 per cent, and no significant interaction was detected. The final multivariable model, adjusted for age and sex, showed an OR of 1·48 (95 per cent c.i. 1·03 to 2·13; P = 0·035) for experiencing LARS symptoms after left‐sided compared with right‐sided colectomy.

The multivariable model, adjusted for age and sex with left‐sided colectomy as reference, resulted in an OR for LARS of 1·27 (95 per cent c.i. 0·75 to 2·13; P = 0·374) for women and an OR of 1·70 (1·03 to 2·79; P = 0·037) for men after right‐sided colectomy.

Relationship between quality of life and LARS score after colectomy

Patients with major LARS versus those with no LARS after colectomy had clinically and statistically significant inferior global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning and social functioning, according to EORTC QLQ‐C30. The difference in many symptom scores of EORTC QLQ‐C30 and ‐CR29 was also clinically significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

EORTC QLQ‐C30 and QLQ‐CR29 scores in relation to low anterior resection syndrome score

| Domain/scale | Mean score | P # | Clinically significant* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No LARS | Minor LARS | Major LARS | |||

| EORTC QLQ‐C30† | |||||

| Global health status/QoL‡, § | 76·4 | 68·5 | 60·6 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Physical functioning‡, § | 85·5 | 80·9 | 72·3 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Role functioning‡, § | 87·0 | 82·4 | 73·3 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Emotional functioning‡, § | 85·6 | 75·9 | 69·7 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Cognitive functioning§ | 86·4 | 83·0 | 77·2 | 0·008 | No |

| Social functioning‡, § | 89·8 | 83·7 | 73·3 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Fatigue‡, ¶ | 23·2 | 28·4 | 43·4 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Nausea and vomiting¶ | 2·4 | 3·9 | 8·2 | 0·069 | No |

| Pain¶ | 10·4 | 14·0 | 20·2 | 0·021 | No |

| Dyspnoea‡, ¶ | 20·0 | 25·5 | 37·9 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Insomnia¶ | 20·4 | 26·7 | 30·2 | 0·017 | No |

| Appetite loss¶ | 5·3 | 4·4 | 11·8 | 0·232 | No |

| Constipation¶ | 12·7 | 14·8 | 19·5 | 0·197 | No |

| Diarrhoea‡, ¶ | 6·7 | 21·7 | 38·4 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Financial difficulties‡, ¶ | 4·3 | 6·7 | 14·9 | 0·024 | Yes |

| EORTC QLQ‐CR29 | |||||

| Body image‡, ¶ | 87·6 | 80·5 | 69·4 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Anxiety‡, § | 72·3 | 63·3 | 56·6 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Weight§ | 82·2 | 77·4 | 71·3 | 0·062 | Yes |

| Sexual interest (men)§ | 59·5 | 63·0 | 67·8 | 0·226 | No |

| Sexual interest (women)§ | 87·3 | 78·4 | 92·2 | 0·096 | No |

| Urinary frequency‡, ¶ | 29·4 | 40·4 | 45·0 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Blood and mucus in stool¶ | 1·3 | 2·5 | 8·3 | 0·011 | No |

| Stool frequency‡, ¶ | 7·9 | 20·1 | 19·5 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Urinary incontinence‡, ¶ | 8·1 | 20·1 | 18·9 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Dysuria¶ | 3·3 | 4·8 | 9·7 | 0·330 | No |

| Abdominal pain‡, ¶ | 8·0 | 10·5 | 21·0 | 0·001 | Yes |

| Buttock pain‡, ¶ | 4·8 | 9·3 | 18·7 | 0·008 | Yes |

| Bloating‡, ¶ | 16·1 | 21·1 | 33·8 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Dry mouth‡, ¶ | 20·8 | 27·4 | 39·0 | 0·001 | Yes |

| Hair loss¶ | 4·3 | 6·3 | 13·8 | 0·157 | No |

| Taste‡, ¶ | 6·2 | 8·2 | 17·4 | 0·030 | Yes |

| Flatulence‡, ¶ | 19·3 | 28·4 | 53·2 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Faecal incontinence‡, ¶ | 3·9 | 6·9 | 30·0 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Sore skin‡, ¶ | 5·4 | 12·2 | 28·3 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Embarrassment‡, ¶ | 5,5 | 16·9 | 35·6 | < 0·001 | Yes |

| Impotence¶ | 43·6 | 56·8 | 48·9 | 0·187 | No |

| Dyspareunia¶ | 92·3 | 92·0 | 88·9 | 0·887 | No |

Clinically significant if more than 10 points of difference between highest and lowest domain score;

score range 0–100;

domain/scale both statistically and clinically significant;

higher score indicates better health‐related quality of life (QoL);

higher score indicates worse health‐related QoL. LARS, low anterior resection syndrome.

Kruskal–Wallis test.

Discussion

Patients reporting minor or major LARS 1 year after segmental colonic resection had decreased scores in global health status and several other aspects of health‐related QoL. Major LARS was more common after right‐sided colectomy, and this effect was more pronounced in men than in women.

Normative data for the LARS score, originally designed to evaluate bowel function after low anterior resection for rectal cancer, have been published recently11. In patients aged 50–79 years, 18·8 per cent of women and 9·6 per cent of men reported major LARS from the general population in Denmark. There is no obvious reason to believe that Sweden would differ from Denmark regarding bowel symptoms. Differences in pelvic anatomy and sequelae after vaginal delivery are often seen as reasons for sex‐related differences in bowel function. In the present population‐based study, women undergoing segmental colonic resection reported a similar proportion of major LARS as in the general population, with small differences between right‐ and left‐sided resections. In men, LARS scores after left‐sided colectomy were comparable to the normative data above, but after right‐sided colectomy the proportion of men with major LARS was twice as high as that in the general population.

The ordinal logistic analysis confirmed these findings. Right‐sided colectomy was an independent risk factor for LARS after segmental colonic resection due to colonic cancer in the multivariable model adjusted for sex and age. The effect of right‐sided colectomy was more pronounced and statistically significant in men, but not in women. The separate analysis of each item of the LARS score indicates that the differences in scores were limited mainly to increased complaints of accidental leakage of liquid stool and urgency after right‐ versus left‐sided colectomy.

In previous studies of rectal cancer, about half of the patients suffered from major LARS after low anterior resection; neoadjuvant radiotherapy, total mesorectal excision (TME), anastomotic leakage, age above 64 years at surgery and female sex have all been cited as risk factors2 7, 12, 13, 14. Thus, a substantially higher proportion of patients treated for rectal cancer have LARS compared with the patients in the present study, where 18·4 per cent described major LARS. The risk factors of radiotherapy and TME are not applicable in colonic cancer, but in the present study surgical complications, adjuvant chemotherapy, open or minimally invasive surgery, BMI and ASA grade were not risk factors for major LARS. The only independent risk factor after adjustment for sex and age was right‐sided colectomy. The fact that patients who had a right‐sided resection also exhibited a higher proportion of minor LARS and a lower proportion of no LARS strengthens the conclusion that this result is robust.

The pathophysiological mechanisms for the differences observed in this study are not clear. In addition to reduced length of the colon, right‐sided colectomy also results in loss of the ileocaecal valve, a small length of terminal ileum, and potential damage to autonomic nerves along the superior mesenteric artery in case of central vessel ligation. Removing the ileocaecal valve leads to faster transportation of bowel contents into the colon and may lead to a reduced capacity for water absorption. Removal of the terminal ileum can lead to reduced absorption of bile acids15, along with bacterial growth in the ileum as a result of loss of the ileocaecal valve12 13. During the past 15 years, the concept of surgery with complete mesocolic excision (CME) has evolved for colonic cancer. Essential steps of CME include complete mobilization of an intact mesocolon and central vascular ligation, resulting in superior specimen quality and a higher number of harvested lymph nodes, thought to be oncologically favourable16. It could be argued that central ligation with harvest of lymph nodes adjacent to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) enhances the risk of injuring the autonomic nerves along the SMA, which would entail a risk of persisting diarrhoea. CME could thus perhaps contribute to differences in functional outcome, as the CME concept has probably been implemented more consistently for right‐sided resections. Data on whether a CME was performed or not were not available in the SCRCR, and CME as a risk factor for LARS could not be evaluated in this study.

Like patients treated by low anterior resection for rectal cancer, the major LARS score identified that patients in the present study also experienced restricted health‐related QoL. Minor LARS had an intermediate impact on QoL, strengthening the association between LARS score and QoL. Functional outcomes after segmental colonic resections have traditionally not been reported in detail. However, selected individuals seem to experience a relevant negative impact on QoL; this warrants attention as liquid stools and urgency can be successfully treated if identified.

This study population was derived from a population‐based registry with a coverage exceeding 98 per cent. The response rate of 60 per cent implies a risk of selection bias. Clinical data of non‐responders were similar to those of the study participants. The higher proportions of women and emergency procedures among non‐responders should have no impact on the present findings.

The LARS score was developed for use after low anterior resection for rectal cancer and is thus not validated for use after surgery for colonic cancer. As the same questionnaire set was sent to all patients, evaluation of LARS scores in patients with colonic cancer, to determine any differences between right‐ and left‐sided resections, still seemed to be of scientific interest.

The PROMs in this study were assessed once 1 year after surgery for colonic cancer, and data on pretreatment function were not available for comparison. Follow‐up data in the SCRCR cover only 3‐ and 5‐year follow‐up, which precludes analysis regarding local recurrence or systemic disease 1 year after surgery. Based on available data from the present study, the effect of oncological outcome on response shift cannot be estimated and may limit the comparison with normative data derived from the general population.

The population‐based design of this cohort study improves the external validity of the reported findings, which are based on adjusted estimates to account for confounding. The cross‐sectional measurement of PROMs and the response rate potentially limit generalizability.

Segmental colonic resection for colonic cancer may impact on bowel function quantified by the LARS score, with negative effects on QoL. Right‐sided colectomy was identified as an independent risk factor, with a more pronounced effect in men than in women. It is time to consider colonic resection increasingly from the patient's point of view. Straightforward right colonic resection can lead to severe functional impairment for some patients. Further investigation of this problem is warranted.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study was provided by the Bengt Ihre Foundation. The authors thank the Stockholm–Gotland Colorectal Cancer Study Group for access to data from the SCRCR. They also thank the team at the Stockholm–Gotland Regional Cancer Centre, T. Singnomklao, J. Järås and C. Lagerros, for excellent help with data collection.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding information Bengt Ihre Foundation, SLS‐590961

References

- 1. Lin YH, Chen HP, Liu KW. Fecal incontinence and quality of life in adults with rectal cancer after lower anterior resection. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015; 42: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ziv Y, Zbar A, Bar‐Shavit Y, Igov I. Low anterior resection syndrome (LARS): cause and effect and reconstructive considerations. Tech Coloproctol 2013; 17: 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Whistance RN, Conroy T, Chie W, Costantini A, Sezer O, Koller M et al; European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group . Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ‐CR29 questionnaire module to assess health‐related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 3017–3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Silva JP. EORTC QLQ CR‐29 evaluation in 500 patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(Suppl): 429. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom‐based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2012; 255: 922–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carrillo A, Enríquez‐Navascués JM, Rodríguez A, Placer C, Múgica JA, Saralegui Y et al Incidence and characterization of the anterior resection syndrome through the use of the LARS scale (low anterior resection score). Cir Esp 2016; 94: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen TY, Wiltink LM, Nout RA, Meershoek‐Klein Kranenbarg E, Laurberg S, Marijnen CA et al Bowel function 14 years after preoperative short‐course radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2015; 14: 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, Emmertsen KJ, Espin E, Jimenez LM et al International validation of the low anterior resection syndrome score. Ann Surg 2014; 259: 728–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Swedish Colorectal Cancer Study Group . Årsrapport Koloncancer 2016 https://www.cancercentrum.se/samverkan/cancerdiagnoser/tjocktarm‐andtarm‐och‐anal/tjock‐‐och‐andtarm/kvalitetsregister/rapporter/ [accessed 25 November 2018].

- 10. King MT. The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ‐C30. Qual Life Res 1996; 5: 555–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Juul T, Elfeki H, Christensen P, Laurberg S, Emmertsen KJ, Bager P. Normative data for the low anterior resection syndrome score (LARS score). Ann Surg 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller LS, Vegesna AK, Sampath AM, Prabhu S, Kotapati SK, Makipour K. Ileocecal valve dysfunction in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a pilot study. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 6801–6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roland BC, Ciarleglio MM, Clarke JO, Semler JR, Tomakin E, Mullin GE et al Low ileocecal valve pressure is significantly associated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Dig Dis Sci 2014; 59: 1269–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wells CI, Vather R, Chu MJ, Robertson JP, Bissett IP. Anterior resection syndrome – a risk factor analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 19: 350–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hawkey CJ, Bosch J, Richter JE, Garcia‐Tsao G, Chan FKL, Garcia‐Tsao G. Textbook of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. John Wiley: Hoboken, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernhoff R, Martling A, Sjövall A, Granath F, Hohenberger W, Holm T. Improved survival after an educational project on colon cancer management in the county of Stockholm – a population based cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015; 41: 1479–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]