Abstract

Background

Despite increased emphasis on patient‐reported outcomes, few studies have focused on abdominal pain symptoms before and after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass (RYGB). The aim of this study was to quantify chronic abdominal pain (CAP) in relation to RYGB.

Methods

Patients with morbid obesity planned for RYGB were invited to participate at a tertiary referral centre from February 2014 to June 2015. Participants completed a series of seven questionnaires before and 2 years after RYGB. CAP was defined as patient‐reported presence of long‐term or recurrent abdominal pain lasting for more than 3 months.

Results

A total of 236 patients were included, of whom 209 (88·6 per cent) attended follow‐up. CAP was reported by 28 patients (11·9 per cent) at baseline and 60 (28·7 per cent) at follow‐up (P < 0·001). Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) scores (except reflux scores) and symptoms of anxiety increased from baseline to follow‐up. Most quality of life (QoL) scores (except role emotional, mental health and mental component scores) also increased. At follow‐up, patients with CAP had higher GSRS scores than those without CAP, with large effect sizes for abdominal pain and indigestion syndrome scores. Patients with CAP had more symptoms of anxiety, higher levels of catastrophizing and lower QoL scores. Baseline CAP seemed to predict CAP at follow‐up.

Conclusion

The prevalence of CAP is higher 2 years after RYGB compared with baseline values.

Introduction

Laparoscopic Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is used widely in the surgical treatment of morbid obesity1. Weight loss, changes in co‐morbidity and aspects of quality of life (QoL) are well documented after RYGB. Adverse effects such as abdominal pain are less well explored. Previously, the authors reported a 33·8 per cent prevalence of chronic or recurrent abdominal pain 5 years after RYGB2. Baseline characteristics, however, were not evaluated. In a Danish study3, 34·2 per cent of the patients operated on with RYGB had been in contact with healthcare professionals owing to abdominal symptoms. Unfortunately, longitudinal studies focusing on abdominal pain and symptoms both before and after RYGB are few4. As these symptoms are common in patients with obesity, interpretations of findings based on postoperative evaluations alone are challenging5, 6.

The causes of abdominal pain after RYGB are heterogeneous and may remain obscure despite investigation. Previous studies3, 7, 8 have used hospital admissions, gastrointestinal surgery and prescription of analgesics as indicators of abdominal pain after RYGB.

The present study hypothesized that the prevalence of chronic abdominal pain (CAP) would increase significantly after RYGB. The main aim of the study was to define the prevalence of CAP as perceived by patients, before and 2 years after RYGB. The study also aimed to evaluate characteristics of patient‐reported symptoms before and after RYGB, as well as exploring potential relationships to psychological characteristics and QoL.

Methods

This was a prospective longitudinal cohort study performed at the Department of Morbid Obesity and Bariatric Surgery, Oslo University Hospital. Patients undergoing RYGB were eligible for study enrolment. The institution is a tertiary referral centre for bariatric surgery, performing 250–300 operations annually. Patients were included from February 2014 to June 2015, and participated in follow‐up consultations from April 2016 to June 2017. RYGB was the dominating institutional bariatric procedure performed during the inclusion period. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (number 2013/1263), Health Region South‐East, Norway, and registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03455998). All participants provided written consent for participation in the study.

Outcomes and definitions

The primary outcome was the prevalence of patient‐reported CAP at consultations before and 2 years after RYGB. CAP was defined as the presence of long‐term or recurrent abdominal pain lasting for more than 3 months9, and patients were asked specifically about this as part of a non‐validated questionnaire. Secondary outcomes included abdominal symptoms other than abdominal pain and symptom characteristics, impact of abdominal pain on QoL and daily functions, and evaluation of potential preoperative predictors of abdominal pain 2 years after RYGB. Early complications were defined as occurring within 30 days of RYGB, and subsequent events as late complications. Complications were graded according to the Clavien–Dindo classification10.

Participants

Eligibility for bariatric surgery were: BMI of 40 kg/m2 or more, or BMI of 35 kg/m2 or above with obesity‐related co‐morbidity; age 18–60 years; and previously failed attempts of sustained weight loss. Patient inclusion was undertaken during the preoperative consultation, in the outpatient clinic. The 2‐year follow‐up visits were also performed in the outpatient setting. On both occasions, the participants responded to a set of questionnaires, followed by consultations with a physician. Participants reporting CAP were offered and referred for diagnostic investigation11. Participants were excluded if they did not understand the Norwegian language, underwent a bariatric procedure other than RYGB, received accompanying cholecystectomy, or were undergoing redo operations.

Surgical procedure and postoperative prescribed supplements

RYGB was performed laparoscopically in all patients, with a gastric pouch of about 25 ml, an antecolic alimentary limb of 150 cm and a biliopancreatic limb of 50 cm12. Mesenteric defects at the jejunojejunostomy and Petersen's space were closed routinely. Patients were discharged 1–2 days after surgery. Oral multivitamin, iron, vitamin D and calcium supplements, and intramuscular vitamin B12 injections were prescribed. Oral ursodeoxycholic acid (Dr Falk Pharma, Freiburg, Germany), 250 mg two times daily for 6 months, was recommended to all patients with the gallbladder in situ to reduce the risk of gallstone formation during the early period of substantial weight loss.

Questionnaires

Seven separate questionnaires were used for comprehensive evaluation of symptoms and relevant patient characteristics. These included one non‐validated questionnaire evaluating abdominal pain characteristics and six other questionnaires: the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale – Self‐administered version (GSRS‐Self©; AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK), ROME III (Rome Foundation, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA), Brief Pain Inventory (BPI; Pain Research Group of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Symptom Evaluation in Cancer Care, Texas, Houston, USA), Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS; McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada/Mapi Research Trust, Lyon, France), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; GL Assessment, London, UK/Mapi Research Trust, Lyon, France), and Short‐Form 36 version 2 (SF‐36®v2; QualityMetric, Lincoln, Rhode Island, USA).

The non‐validated abdominal pain questionnaire has an initial question: ‘Are you experiencing long term or recurrent abdominal pain lasting for more than three months?’ If answering ‘yes’, the participant was instructed to respond to the rest of the items regarding pain characteristics. A figure with the four abdominal quadrants and the periumbilical area was used by patients for pain localization. Pain severity was graded along the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) from 0 to 10 (0, no pain; 10, worst imaginable pain), with cut‐off values: mild (0–5), moderate (6–7) and severe (8–10)13. Interference with sleep, daily activities and work was graded on the same NRS (0, not affected; 10, completely affected), with the same cut‐off values.

GSRS consists of 15 items; participants respond on a seven‐point Likert scale (1, no discomfort; 7, severe discomfort) for each item. The item scores are given as total score and five syndrome scores (abdominal pain, gastrointestinal reflux, diarrhoea, indigestion, constipation syndrome)14. A mean value of 3 or more was used as the cut‐off for bothersome symptoms.

The ROME III questionnaire was used to identify functional gastrointestinal disease (irritable bowel syndrome, IBS), following a predefined algorithm of diagnostic criteria15.

The BPI was used for further assessment of abdominal pain and other pain symptoms. Areas of pain were specified on a body figure, followed by assessment of pain severity, use of pain medications and their pain relief, and pain interference with functions16.

The PCS was used to assess the impact of catastrophic thinking on pain experience. The questionnaire consists of 13 items representing thoughts/feelings related to past painful experience. Participants responded on a five‐point Likert scale (0, not at all; 4, all the time), grading how often they experienced these thoughts/feelings when experiencing pain. The PCS gives a total score and three subscale scores of catastrophizing (rumination, magnification and helplessness). Cut‐off values corresponding to the 75th percentile (total scores 30 or more, rumination scores 11 or more, magnification scores 5 or more, and helplessness scores 13 or more) were used to indicate clinically relevant levels of catastrophizing17.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were evaluated by 14 items on the HADS, with each item scored from 0 to 3. Seven items assessed anxiety and seven assessed depression. Adding the scores of each item gave subscores for anxiety and depression ranging from 0 to 21. A subscore of 8 or more was regarded as symptom of anxiety and/or depression18.

SF‐36®v2 (4‐week recall) was used to evaluate QoL. It consists of 36 items grouped into eight health domains. Sums of all items within each domain are transformed into a 0–100 scale (0, maximum disability; 100, no disability). Two summary scores are given: the physical and the mental component summary scores. Norm‐based scoring was not used. SF‐36®v2 was scored using Health Outcomes Scoring Software version 5.1 (Optum, Lincoln, Rhode Island, USA)19.

Statistical analysis

For univariable analyses, Student's t test, Wilcoxon signed rank test or Wilcoxon rank sum test/Mann–Whitney U test were used as appropriate when comparing continuous variables. McNemar's test or the χ2 test was used for comparison of categorical variables. Continuous variables are presented as mean(s.d.) values, and categorical variables as number with proportion as percentage. Effect sizes of the changes in scores between two means were estimated with Cohen's d (continuous variables). Cohen's d was calculated as the difference between two means, divided either by the pooled standard deviation (independent groups) or by the standard deviation of the difference (dependent groups). Suggested cut‐off values for Cohen's d, used cautiously, were: small 0·2, medium 0·5 and large 0·820, 21.

CAP at 2 years was used as the outcome variable in the logistic regression model. All predictors were entered simultaneously and chosen by clinical relevance. The model was limited to eight preoperative variables: age, sex, BMI, musculoskeletal pain, gastro‐oesophageal reflux, symptoms of anxiety (from HADS), IBS diagnosis (from ROME III) and preoperative CAP.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS® Statistics version 25 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

A total of 271 consecutive patients were scheduled for RYGB during the study period from February 2014 to June 2015. Of these, 25 were missed for inclusion at the outpatient ward, leaving 246 patients (90·8 per cent) considered eligible for study enrolment. All were included, but ten were subsequently excluded (not operated on, 5; sleeve gastrectomy, 3; redo surgery, 1; simultaneous cholecystectomy, 1), resulting in a final preoperative study population of 236 patients. Two years after RYGB, 209 of the 236 patients (88·6 per cent) attended for follow‐up. Patient characteristics before and after RYGB are listed in Table 1. Mean percentage total weight loss at 2 years was 31·3 per cent.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics before and 2 years after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass

| Baseline (n = 236) | 2‐year follow‐up (n = 209) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 44(9) | 46(9) |

| Sex ratio (F : M) | 169 : 67 | 154 : 55 |

| Weight (kg)* | 126·8(20·8) | 86·4(17·6) |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 43·2(5·9) | 29·2(4·7) |

| Civil status | ||

| Living with someone | 154 (65·3) | 148 of 207 (71·5) |

| Living alone | 82 (34·7) | 59 of 207 (28·5) |

| Employment status | ||

| Working full‐time or part‐time/student | 155 of 234 (66·2) | 145 (69·4) |

| Unemployed/sick leave/disability pension | 79 of 234 (33·8) | 64 (30·6) |

| Co‐morbidities† | ||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 58 of 232 (25·0) | 14 of 199 (7·0) |

| Hypertension | 102 of 232 (44·0) | 26 of 199 (13·1) |

| Gastro‐oesophageal reflux | 97 of 232 (41·8) | 8 of 199 (4·0) |

| Hypothyroidism | 22 of 231 (9·5) | 17 of 199 (8·5) |

| Depression | 35 of 230 (15·2) | 32 of 199 (16·1) |

| Anxiety | 28 of 231 (12·1) | 23 of 199 (11·6) |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 108 of 230 (47·0) | 96 of 199 (48·2) |

| Gallstones | 20 of 231 (8·7) | 17 of 198 (8·6) |

| Abdominal surgery besides RYGB‡ | 106 of 234 (45·3) | 25 of 193 (13·0) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean(s.d.).

Symptomatic patient‐reported co‐morbidities.

Abdominal surgery from any cause; at follow‐up, 18 of 25 surgical procedures were due to complications after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass (RYGB).

Over the study interval, complications were seen in 26 of 209 patients (12·4 per cent): six grade I, two grade II and 18 grade IIIb. One of seven patients with early complications required surgery (adhesiolysis with small bowel resection). Seventeen of 19 patients with late complications required surgery (cholecystectomy, 6; internal hernia repair, 5; mesenteric defect closure, 2; umbilical hernia repair, 2; concomitant adhesiolysis with mesenteric defect closure and cholecystectomy, 1; sclerotherapy of bleeding ulcer at the enteroenteral anastomosis, 1).

Questionnaire data sampling

Questionnaire response rates for the GSRS, ROME III, BPI, PCS, HADS and SF‐36®v2 at baseline and follow‐up were: 86 and 98, 94 and 82, 94 and 92, 96 and 95, 99 and 97, and 81 and 97 per cent respectively.

Chronic abdominal pain and symptoms

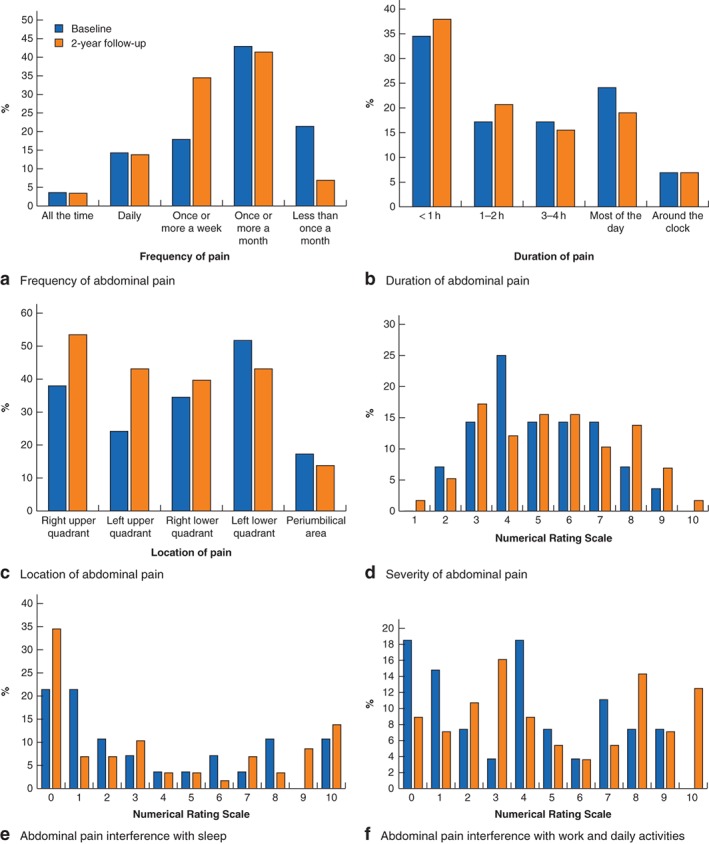

At baseline and follow‐up, 28 of 236 patients (11·9 per cent) and 60 of 209 (28·7 per cent) respectively reported CAP (P < 0·001). At 2 years, CAP was of new onset in 46 of the 60 patients (77 per cent). Of the 28 patients reporting CAP at baseline, ten (36 per cent) did not report CAP 2 years after RYGB. Abdominal pain characteristics are presented in Fig. 1 a–f. The location of abdominal pain was distributed widely but reported to be more concentrated in the left lower quadrant before RYGB and in the upper right quadrant after RYGB (Fig. 1 c). Pain interference with sleep, work and daily activities is presented in Fig. 1 e,f. With multiple choice questionnaires inquiring about all types of treatment received, 16 of 28 patients (57 per cent) with CAP at baseline and 34 of 58 (59 per cent) with CAP at follow‐up reported no treatment for abdominal pain (P = 0·250). At baseline and follow‐up, 17 of 28 (61 per cent) and 30 of 60 (50 per cent) patients with CAP, respectively, reported using any type of analgesia (P = 0·500). Opioids and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs were used by seven of 28 (25 per cent) and four of 28 (14 per cent) patients with CAP at baseline, and 13 of 60 (22 per cent) were using opioid/opioid‐like analgesics at 2 years (P = 0·337).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of patient‐reported abdominal pain at baseline and 2 years after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass. a Frequency, b duration, c location and d severity of abdominal pain, and interference of abdominal pain with e sleep and f work and daily activities. Twenty‐eight patients reported abdominal pain at baseline and 60 at 2 years after surgery; patients with missing data were not included in the analyses

Other treatments, such as physiotherapy, psychotherapy and treatment at a pain clinic, were reported in eight of 28 patients (29 per cent) at baseline and 12 of 57 (21 per cent) at follow‐up (P = 1·000).

Among patients with CAP at follow‐up, complications were seen in 14 of 60 patients (23 per cent). Clavien–Dindo grade IIIb complications were seen in nine of 60 patients (15 per cent) with CAP. In patients without CAP at follow‐up, complications were seen overall in 12 of 141 (8·5 per cent) and Clavien–Dindo grade IIIb in nine of 141 (6·4 per cent).

Other abdominal and gastrointestinal symptoms

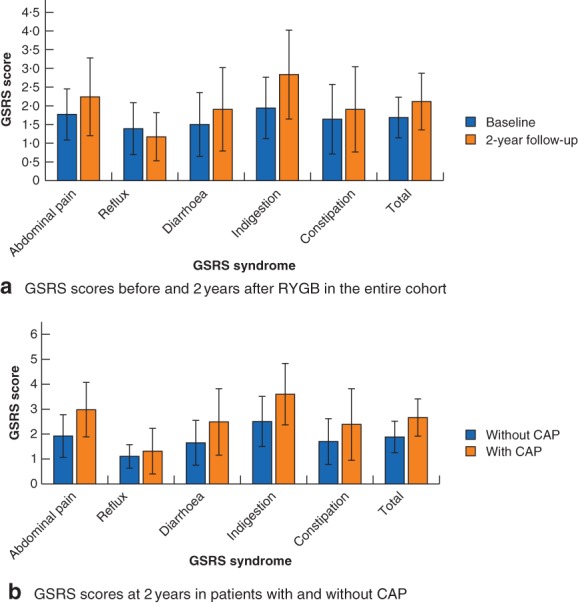

For the entire cohort, significant increases in mean scores for all GSRS syndromes, with a significant decrease in reflux syndrome scores, were seen from baseline to 2 years after RYGB (Fig. 2 a).

Figure 2.

Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale syndrome scores before and after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass. Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) syndrome scores a before (236 patients) and 2 years after (209 patients) Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass, and b at 2 years in 60 patients with and 141 without chronic abdominal pain (CAP). Values are mean(s.d.). Patients with missing data are not included in the analyses. a P = 0·001 for constipation score, P < 0·001 for all other scores (baseline versus 2 years, Wilcoxon signed rank test; effect size less than 0·5 for abdominal pain, reflux, diarrhoea and constipation scores, 0·5–0·8 for indigestion and total scores). b P = 0·031 for reflux score, P = 0·001 for constipation score, P < 0·001 for all other GSRS scores (patients with versus those without CAP, Wilcoxon rank sum test/Mann–Whitney U test; effect size less than 0·5 for reflux scores, 0·5–0·8 for diarrhoea and constipation scores, and above 0·8 for abdominal pain, indigestion and total scores)

At 2 years, patients with CAP scored significantly lower for reflux syndrome, but significantly higher for all other GSRS syndromes compared with patients without CAP. Large effect sizes were seen for abdominal pain and indigestion syndromes (Fig. 2 b). With GSRS cut‐off values of 3 or above for abdominal pain syndrome, 17 of 202 (8·4 per cent) at baseline and 57 of 203 (28·1 per cent) at follow‐up had bothersome abdominal pain symptoms (P < 0·001).

At baseline, eight of 24 patients (33 per cent) with CAP and 11 of 180 (6·1 per cent) without CAP had IBS, as diagnosed by the ROME III questionnaire (P < 0·001). At 2 years after RYGB, 26 of 46 patients (57 per cent) with CAP and 15 of 118 (12·7 per cent) without CAP had IBS (P < 0·001).

There were no significant changes in overall mean BPI scores in the entire cohort between baseline and follow‐up for pain severity scores (P = 0·510, effect size −0·0), or in pain interference scores (P = 0·054, effect size −0·2). At follow‐up, patients with CAP had significantly higher mean BPI scores than those without CAP, for both pain severity (3·2(2·1) versus 2·0(2·3) respectively) and pain interference (3·0(2·6) versus 1·7(2·3)) (P < 0·001, effect score 0·5 for both measures).

By figure evaluation of all possible pain regions, the abdominal region was shaded as the area of pain in 8·7 and 30·8 per cent of the entire cohort at baseline and follow‐up respectively (P < 0·001).

Psychosocial characteristics

Mean total PCS scores at baseline were 11·7(8·5) and at follow‐up 12·7(10·7) (P = 0·270, effect size 0·1). From baseline to follow‐up, clinically relevant levels of catastrophizing (score at 75th percentile or above) increased significantly for rumination type (P = 0·001) and total score (P = 0·004). At 2 years, patients with CAP had significantly higher levels of catastrophizing for all subtypes and for total score, compared with those without CAP.

According to the HADS, 31 of 228 (13·6 per cent) of all patients at baseline and 42 of 197 (21·3 per cent) at follow‐up had anxiety (P < 0·001). Similarly, depression was seen in 25 of 228 (11·0 per cent) at baseline and 17 of 197 (8·6 per cent) at follow‐up (P = 0·678).

At follow‐up, anxiety was seen in 19 of 58 patients (33 per cent) of with CAP and 23 of 138 (16·7 per cent) without CAP (P = 0·012). The corresponding values for depression were seven of 58 (12 per cent) and ten of 138 (7·2 per cent) (P = 0·274).

Quality of life

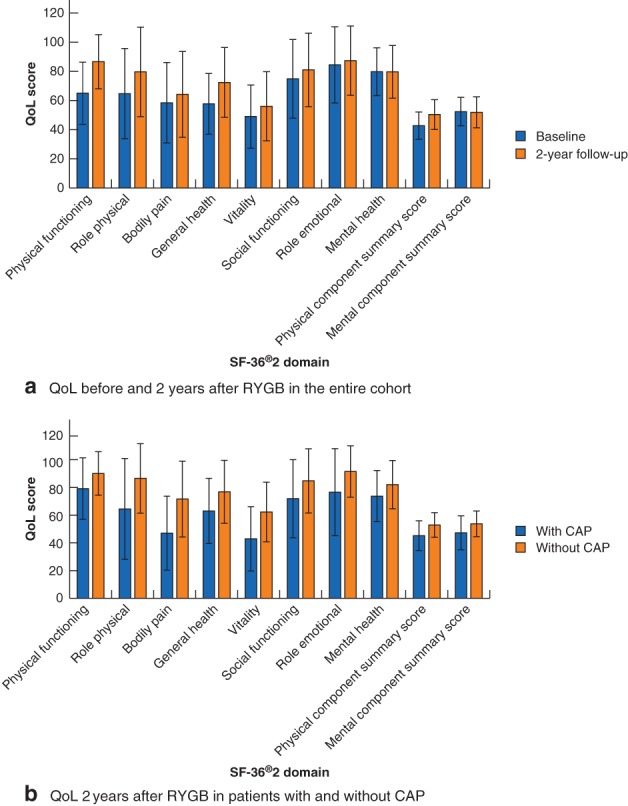

For the entire cohort, mean physical component summary scores at baseline and follow‐up were 42·8(9·4) and 50·4(10·3) respectively. The corresponding mental component summary scores were 52·4(9·8) and 51·9(10·6). The scores improved significantly for all SF‐36® health domains at follow‐up, except for role emotional and mental health (Fig. 3 a).

Figure 3.

Quality of life scores by Short Form 36 health domains before and after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass. Quality of life (QoL) scores by Short Form 36 version 2 (SF‐36®v2) domains a before (236 patients) and 2 years after (209 patients) Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass, and b at 2 years in 60 patients with and 141 without chronic abdominal pain (CAP). Values are mean(s.d.). Patients with missing data are not included in the analyses. a P < 0·001 for physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), general health (GH) and physical component summary (PCS) scores, P = 0·031 for bodily pain (BP) score, P = 0·002 for vitality (VT) score, P = 0·001 for social functioning (SF) score (baseline versus 2 years, Wilcoxon signed rank test; effect size less than 0·5 for RP, BP, VT and SF scores, 0·5–0·8 for GH and PCS scores, and above 0·8 for PF score). There was no significant change in QoL scores for role emotional (RE) (P = 0·362), mental health (MH) (P = 0·469) or mental component summary (MCS) (P = 0·638) scores (effect size less than 0·5 for all). b P = 0·001 for SF, RE, MH and MCS scores, P < 0·001 for all other health domains (patients with versus those without CAP, Wilcoxon rank sum test/Mann–Whitney U test; effect size less than 0·5 for SF and MH scores, 0·5–0·8 for PF, RP, GH, RE, PCS and MCS scores, and above 0·8 for BP and VT scores)

At 2 years, patients with CAP had significantly lower scores than those without CAP for all health domain scores and both component summary scores (Fig. 3 b).

Predictors of chronic abdominal pain

Being female and having gastro‐oesophageal reflux symptoms, anxiety, IBS or CAP at baseline increased the crude odds ratio of having CAP at follow‐up. In the multivariable analyses using these predictors plus BMI and musculoskeletal pain, only baseline CAP was a significant predictor of CAP at follow‐up (Table S1, supporting information).

Discussion

An increased proportion of patients reported CAP 2 years after RYGB, rising from 11·9 to 28·7 per cent. This was accompanied by increases in reported bothersome GSRS abdominal pain symptoms, from 8·4 per cent at baseline to 28·1 per cent at 2 years, and by the BPI figure evaluation of pain regions, where the abdominal region was shaded as area of pain in 8·7 per cent of patients at baseline and in 30·8 per cent at follow‐up. Only baseline CAP predicted CAP significantly at follow‐up. The main clinical impact of these findings is that evaluation of abdominal symptoms should form part of follow‐up consultations after RYGB. Information regarding this potential outcome should be provided to patients at the point of decision‐making for surgery.

Similar findings 2 years after RYGB have been reported previously22, although without baseline analyses. At follow‐up, patients with CAP reported more gastrointestinal symptoms than those without CAP did. Large effect sizes for abdominal pain and indigestion syndrome scores were observed in patients with CAP compared with those in patients without CAP at 2 years. Thus, symptoms of indigestion may be related to CAP after RYGB.

All patients were prescribed ursodeoxycholic acid for 6 months after RYGB to reduce or prevent gallstone formation. According to institutional guidelines, ultrasonography was not routinely performed, and the true rate of patients with gallstones remains unknown, including those who are asymptomatic. Still, of all five abdominal pain areas (Fig. 1 c), the right upper quadrant was marked as location of abdominal pain in 53 per cent of patients with CAP at follow‐up. As the epigastric region was not a separate choice of pain location, pain in this area may have been allocated by the patients to one of the two upper quadrants.

Some 23 per cent of the 60 patients with CAP at follow‐up had complications after surgery. Such complications may contribute to the development of CAP.

Chronic abdominal pain in the morbidly obese population has been reported previously23, 24, with a prevalence of 12–24 per cent. Furthermore, obesity is associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain, especially chronic low back pain23, 25. Before and after RYGB, musculoskeletal pain was reported by about 48 per cent of the study population. Interestingly, the overall BPI pain severity scores did not seem to change from baseline to 2 years. These findings may indicate that patients may also experience symptoms of pain from other body regions, adding complexity to interpretations of findings. In the present analyses, there were no interactions between total weight loss and CAP at 2‐year follow‐up. Preoperative BMI did not predict CAP at follow‐up.

Pain was reported as moderate to severe in 39 per cent of patients with CAP at baseline and in 48 per cent of those with CAP at follow‐up (Fig. 1 d). Moderate to severe pain, interference with sleep, work and daily life was reported in about 30 per cent at baseline and follow‐up. As specified by the BPI questionnaire at follow‐up, the interference of pain with daily functions and its effect on wellbeing was significantly greater in patients with CAP than in those without. As 39 (65 per cent) of the 60 patients with CAP at follow‐up were employed full‐time or part‐time, most patients appeared to continue daily life despite symptoms that interfered with function and wellbeing26. Patients with CAP had worse QoL scores than those without CAP at follow‐up, despite a general improvement in QoL for the study population as a whole. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere3, where overall wellbeing was improved after RYGB despite a substantial proportion of the population experiencing adverse symptoms. The perception of abdominal pain and the potentially negative impact on QoL and wellbeing should be considered in the context of total symptom changes after RYGB.

Catastrophizing increased from baseline to follow‐up in the entire cohort, as well as in patients with CAP compared with those without CAP at 2 years. Women tend to have higher scores for all types, except magnification type27. The significantly higher levels of catastrophizing at follow‐up may be associated with CAP. Catastrophizing may be a target for therapeutic intervention, and should be explored further in patients experiencing CAP28.

Few studies2, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 have focused primarily on abdominal pain after RYGB. A Dutch study34 described a prevalence of abdominal pain of 21·6 per cent at 33·5 months after bariatric surgery (mostly RYGB procedures). At a rate of 54·4 per cent, abdominal pain was one of the most common complaints after RYGB in another study3, whereas in a third7 abdominal pain accounted for 15 per cent of all long‐term complications after RYGB requiring hospital admission. A cohort and register‐based study with median follow‐up of 6·5 years reported abdominal pain in 26·1 per cent of patients (92 per cent RYGB), and in 13·5 per cent of patients receiving medical treatment for obesity8. One study33 that did examine patient‐reported abdominal pain after RYGB reported an increase from 17 per cent at baseline to 32 per cent at 2 years. Data from comparative studies of abdominal pain after procedures such as RYGB, sleeve gastrectomy and single anastomosis gastric bypass may lead to findings relevant for choice of procedure. Ongoing trials that may allow data in this regard include the By‐Band‐Sleeve trial35 and the Swedish Bypass Equipoise Sleeve (BEST) trial.

Strengths of the present study include the longitudinal cohort design with in‐depth analyses of each patient. Inclusion and follow‐up took place as in‐office consultations with a physician, and the follow‐up rate was close to 90 per cent. Extensive evaluations of abdominal and gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as psychological symptoms, were done with validated questionnaires and had a high response rate. The use of effect size estimates may add clinical relevance to the statistical observations. The single‐centre design may affect the external validity of this study, and future studies should explore this topic in other RYGB cohorts. The lack of evaluation of the prevalence of sick leave or disability benefits represents a limitation. It appears unlikely that the increase in symptoms described during a 2‐year period would happen without any surgical intervention. A control group, however, may have added relevant information for the interpretation of findings. Outcomes of the diagnostic investigation of CAP were not the focus of the present study, although, when evaluated in a different cohort at this centre, a precise cause for CAP 5 years after RYGB remained unknown in a significant proportion of patients11.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1 Preoperative predictors of chronic abdominal pain 2 years after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass

Funding information

No funding

Presented in part to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Obesity Week meeting, Nashville, Tennessee, USA, November 2018

References

- 1. Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Vitiello A, Zundel N, Buchwald H et al. Bariatric surgery and endoluminal procedures: IFSO worldwide survey 2014. Obes Surg 2017; 27: 2279–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Høgestøl IK, Chahal‐Kummen M, Eribe I, Brunborg C, Stubhaug A, Hewitt S et al. Chronic abdominal pain and symptoms 5 years after gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 2017; 27: 1438–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gribsholt SB, Pedersen AM, Svensson E, Thomsen RW, Richelsen B. Prevalence of self‐reported symptoms after gastric bypass surgery for obesity. JAMA Surg 2016; 151: 504–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mala T, Høgestøl I. Abdominal pain after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Scand J Surg 2018; 107: 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aasbrenn M, Høgestøl I, Eribe I, Kristinsson J, Lydersen S, Mala T et al. Prevalence and predictors of irritable bowel syndrome in patients with morbid obesity: a cross‐sectional study. BMC Obes 2017; 4: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fysekidis M, Bouchoucha M, Bihan H, Reach G, Benamouzig R, Catheline JM. Prevalence and co‐occurrence of upper and lower functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients eligible for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2012; 22: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gribsholt SB, Svensson E, Richelsen B, Raundahl U, Sørensen HT, Thomsen RW. Rate of acute hospital admissions before and after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass surgery: a population‐based cohort study. Ann Surg 2018; 267: 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jakobsen GS, Småstuen MC, Sandbu R, Nordstrand N, Hofsø D, Lindberg M et al. Association of bariatric surgery vs medical obesity treatment with long‐term medical complications and obesity‐related comorbidities. JAMA 2018; 319: 291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Greenberger NJ. Chronic Abdominal Pain and Recurrent Abdominal Pain; 2018. http://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/gastrointestinal‐disorders/symptoms‐of‐gi‐disorders/chronic‐and‐recurrent‐abdominal‐pain [accessed 22 December 2018].

- 10. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blom‐Høgestøl IK, Stubhaug A, Kristinsson JA, Mala T. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic abdominal pain 5 years after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018; 14: 1544–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Hamad G, Eid GM, Mattar S, Cottam D et al. Laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery: current technique. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2003; 13: 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boonstra AM, Stewart RE, Köke AJ, Oosterwijk RF, Swaan JL, Schreurs KM et al. Cut‐off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the numeric rating scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: variability and influence of sex and catastrophizing. Front Psychol 2016; 7: 1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kulich KR, Madisch A, Pacini F, Piqué JM, Regula J, Van Rensburg CJ et al. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire in dyspepsia: a six‐country study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008; 6: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: new standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2006; 15: 237–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain 2004; 5: 133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995; 7: 524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF‐36 total score as a single measure of health‐related quality of life: scoping review. SAGE Open Med 2016; 4: 2050312116671725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ialongo C. Understanding the effect size and its measures. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2016; 26: 150–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Durlak JA. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. J Pediatr Psychol 2009; 34: 917–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boerlage TC, van de Laar AW, Westerlaken S, Gerdes VE, Brandjes DP. Gastrointestinal symptoms and food intolerance 2 years after laparoscopic Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wright LJ, Schur E, Noonan C, Ahumada S, Buchwald D, Afari N. Chronic pain, overweight, and obesity: findings from a community‐based twin registry. J Pain 2010; 11: 628–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eriksen J, Jensen MK, Sjøgren P, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK. Epidemiology of chronic non‐malignant pain in Denmark. Pain 2003; 106: 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cooper L, Ells L, Ryan C, Martin D. Perceptions of adults with overweight/obesity and chronic musculoskeletal pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: e776–e786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hølen JC, Lydersen S, Klepstad P, Loge JH, Kaasa S. The Brief Pain Inventory: pain's interference with functions is different in cancer pain compared with noncancer chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2008; 24: 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA, Hauptmann W, Jones J, O'Neill E. Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J Behav Med 1997; 20: 589–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kvalem IL, Bergh I, Sogg S, Mala T. Psychosocial characteristics associated with symptom perception 1 year after gastric bypass surgery – a prospective study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017; 13: 1908–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bal B, Shope T, Finelli FC, Koch TR. Prevalence and causes of abdominal pain following fully divided Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass surgery. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 187. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ma IT, Madura JA II. Gastrointestinal complications after bariatric surgery. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2015; 11: 526–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greenstein AJ, O'Rourke RW. Abdominal pain after gastric bypass: suspects and solutions. Am J Surg 2011; 201: 819–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Abdominal pain in the Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass patient. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113: 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elias K, Bekhali Z, Hedberg J, Graf W, Sundbom M. Changes in bowel habits and patient‐scored symptoms after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018; 14: 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pierik AS, Coblijn UK, de Raaff CAL, van Veen RN, van Tets WF, van Wagensveld BA. Unexplained abdominal pain in morbidly obese patients after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017; 13: 1743–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rogers CA, Reeves BC, Byrne J, Donovan JL, Mazza G, Paramasivan S et al.; By‐Band‐Sleeve study investigators . Adaptation of the By‐Band randomized clinical trial to By‐Band‐Sleeve to include a new intervention and maintain relevance of the study to practice. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 1207–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Preoperative predictors of chronic abdominal pain 2 years after Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass