Abstract

Background

Whether the portal/superior mesenteric vein (PV) should be resected during pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) based on preoperative CT or intraoperative findings is controversial.

Methods

This was a retrospective study with data of patients who had undergone pancreatoduodenectomy for PDAC between 2002 and 2016 in a tertiary referral centre. Based on the extent of contact between the PV and tumour on CT, patients were categorized into: group 1, no contact; group 2, contact 180° or less; group 3, contact greater than 180°. Extent of pathological PV invasion (pPV) (no invasion, pv0; invasion to tunica adventitia, pv1; invasion to media, pv2; invasion to intima, pv3) was compared with patient survival. To assess the feasibility of performing PV resection (PVR) based on intraoperative findings, the prognosis of patients in groups 1 and 2 with pv0 and no PVR (PVR(−)pv0) was compared with that of patients who had PVR (PVR(+)pv0), selected using propensity score matching.

Results

Groups 1, 2 and 3 comprised 230, 232 and 38 patients respectively, and PVR was performed in 10·9, 73·3 and 95 per cent of them (P < 0·001). Extent of pPV differed significantly (P < 0·001). The positive predictive value of radiological tumour contact with PV in predicting positive pPV was 42·6 per cent. In 64 patients with PVR(−)pv0 and 64 matched patients with PVR(+)pv0, the R0 resection rate (66 versus 73 per cent respectively; P = 0·337) and survival (median 32·4 versus 32·1 months; P = 0·780) were not significantly different.

Conclusion

PVR is needed only when the tumour is in clear contact with the PV and cannot be detached during surgery.

Introduction

Pathologically identified invasion of the portal or superior mesenteric vein (PV) by pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a prognostic factor for survival1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. However, several studies7, 8, 9, 10, including large multi‐institutional series, have shown that long‐term survival after PV resection (PVR) during pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is comparable to that achieved by standard PD without PVR, when R0 resection was performed.

Preoperative diagnosis of PV involvement is generally made on the basis of multidimensional CT. In general, PDAC with more than 180° contact between tumour and PV is considered as borderline resectable PDAC, because of PV invasion (BR‐PV)11.

The accuracy of CT in predicting pathological PV invasion (pPV) and postoperative prognosis is low2 10, 12, 13, 14. In the authors' institution, PVR is indicated only when the pancreatic head cannot be detached from the PV during PD. Whether or not PVR should be performed in all patients whose preoperative CT shows tumour contact with the PV has been rarely evaluated15. This study aimed to address accuracy of CT in predicting pPV and the feasibility of performing PVR based on intraoperative findings during PD.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients who underwent PD at the National Cancer Centre Hospital, a tertiary referral centre in Japan in which approximately 300–350 patients undergo hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery annually. Patients who had undergone PD for pathologically proven PDAC between 2002 and 2016 were eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients who had PD after neoadjuvant chemotherapy were excluded, because evaluation of resectability in these patients was different from that in patients having upfront surgery owing to difficulty in accurate radiological evaluation of the pathological response of the remnant tumour. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Centre.

Perioperative management

Preoperative evaluation of the possible diagnosis and extent of disease was based mainly on multidetector‐row CT and ultrasonography findings. Biopsy was performed only when radiological images were not typical of PDAC or preoperative chemotherapy was to be administered. Few patients received preoperative chemotherapy during the study period, the exceptions being patients registered in another clinical trial.

Biliary drainage was performed either endoscopically or percutaneously in patients with obstructive jaundice. Most patients underwent biliary drainage before referral. PD was considered to be indicated when serum total bilirubin concentration reached 5·0 mg/dl or less.

PVR was usually performed as one of the last steps of PD, after transection of the pancreatic parenchyma and dissection of the pancreatic head plexus, at which stage the only attachment of the pancreatic head was to the PV. When it was difficult to dissect the pancreas from the PV, PVR was performed by either wedge or sleeve resection, depending on the extent of the attached area.

From 2008, adjuvant chemotherapy with either gemcitabine16 or S‐117 was administered routinely after surgery. Diagnosis of tumour recurrence was made on the basis of CT performed every 3–6 months or when concentrations of tumour marker (carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) or carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19‐9) increased.

Data collection

Institutional charts were reviewed to extract data. Preoperative CT scans were reviewed and each patient was classified on the basis of extent of PV contact with tumour as follows: group 1, no contact; group 2, contact between tumour and PV of 180° or less; and group 3, contact between tumour and PV of more than 180°. Pathologically identified PV invasion to tunica adventitia, media and intima was defined as pv1, pv2 and pv3 respectively; no pPV was denoted as pv0. In addition to CT findings, clinical profiles included preoperative patient age, sex, CEA level, CA19‐9 concentration, duration of surgery, amount of blood loss, postoperative morbidity, recurrence‐free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS). Postoperative morbidity was classified according to the Clavien–Dindo criteria18, morbidity of grade III or above being defined as major. Pancreatic fistula was defined according to the criteria of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery19. The sites of initial tumour recurrence were also recorded. Development of lymph node enlargement or soft tissue swelling around the PV, superior mesenteric artery, coeliac artery or pancreatic stump were considered to denote local recurrence, whereas recurrences at other sites were defined as distant. Recorded pathological profiles other than PV invasion included tumour size, serosal invasion, retropancreatic tissue invasion, distal bile duct invasion, duodenal invasion, extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion, and R status with the sites of tumour exposure in patients with R1 resection. R status was defined as R1 when the distance between the tumour and any of the surgical margin was 0 mm.

Statistical analysis

Distribution of pPV grades, pathologically assessed extent of tumour, R status, stages according to the eighth edition of the UICC classification20, and short‐ and long‐term outcomes were compared between groups 1, 2 and 3. To evaluate whether PVR is indicated in all patients in whom preoperative CT suggests PV invasion, the prognosis of patients in groups 2 and 3 with pv0 and without PVR (PVR(−)pv0) who had undergone PD was compared with that of matched patients with PVR (PVR(+)pv0), selected by the propensity score nearest‐neighbour one‐to‐one matching method. The propensity score was estimated by the predicted probability, calculated by a logistic regression model using variables that could be evaluated before surgery, including patient age, sex, CA19‐9 concentration and tumour size. Sites of initial recurrence were also compared.

Continuous data are expressed as median (range) values and compared with the Mann–Whitney U test for two‐group comparisons and the Kruskal–Wallis test for three‐group comparisons. Categorical data were compared by Pearson's χ2 or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log rank test. Univariable and multivariable analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazards regression models to identify the prognostic factors. Variables with P < 0·100 in univariable analysis were entered into the multivariable model. Control group patients were selected using propensity score matching. P < 0·050 was considered to denote a statistically significant difference. For the preoperative profiles, data acquired on the latest date before PD were used, and the date of tumour recurrence was defined as the first day on which the recurrence was confirmed by CT or other radiological images.

Results

During the study period, 520 patients underwent PD. Eighteen patients who received preoperative chemotherapy and two with carcinoma in situ were excluded. PVR was performed in 231 of the remaining 500 patients (46·2 per cent), and included wedge resection in 79 (15·8 per cent) and sleeve resection in 152 (30·4 per cent). Patch grafts (gonadal vein, 9 patients; round ligament, 3) were used for primary closure after wedge resection in 12 patients. Reconstruction after sleeve resection was performed by end‐to‐end anastomosis in 149 patients and by use of interposition grafts in two (left renal vein, 1 patient; middle colic vein, 1). In one patient the thin superior mesenteric vein was not reconstructed, although a well developed first jejunal vein and inferior mesenteric vein were preserved. Review of preoperative CT scans resulted in allocation of 230, 232 and 38 patients to groups 1, 2 and 3 respectively.

Comparisons between groups 1, 2 and 3

Table 1 shows baseline and tumour characteristics, and surgical data for patients in the three groups. Duration of surgery was shorter and the amount of blood loss was less in group 1 than in groups 2 and 3. The incidence of postoperative morbidity, particularly pancreatic fistula, was higher in group 1 than in groups 2 and 3. Four patients died from postoperative complications, including two in group 1 and two in group 2. A higher proportion of patients underwent PVR in group 3 than in group 2. R1 resection status was attributable mostly to a positive dissected peripancreatic margin rather than the pancreatic cut‐end margin. The most common tumour‐positive site was the pancreatic head plexus, which was involved in 40 patients, followed by retropancreatic fat tissue in 35 patients, PV sulcus or around the resected PV in 31 patients, and other sites in 17 patients. The R1 rate was significantly higher in groups 2 and 3 than in group 1, but no different between groups 2 and 3. Tumours were smaller in group 1, and tumour extension outside the pancreas was also significantly different between the groups, except for distal bile duct or duodenal invasion. Because T category is based mainly on tumour size, there were significant differences in T category distribution between the three groups. Stage distribution, however, was not significantly different.

Table 1.

Perioperative variables according to indicated study group

| Group 1 (n = 230) | Group 2 (n = 232) | Group 3 (n = 38) | P † | P ‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 68 (20–86) | 66 (33–89) | 66 (27–83) | 0·206§ | 0·587§ |

| Sex ratio (M : F | 146 : 84 | 129 : 103 | 17 : 21 | 0·047 | 0·213 |

| CEA (ng/ml)* | 2·8 (0·6–51·8) | 2·8 (0·6–243·0) | 2·9 (0·8–49·4) | 0·794§ | 0·565§ |

| CA19‐9 (units/ml) | 103 (0–21 250) | 126 (0–46 000) | 241 (1–4250) | 0·149§ | 0·145§ |

| Duration of surgery (min)* | 491 (251–795) | 537 (300–1026) | 558 (328–930) | < 0·001§ | 0·393§ |

| Blood loss (ml)* | 755 (70–3370) | 898 (86–4322) | 1151 (266–3910) | < 0·001§ | 0·063§ |

| PVR | 25 (10·9) | 170 (73·3) | 36 (95) | < 0·001 | 0·003 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 105 (45·7) | 108 (46·6) | 15 (39) | 0·719 | 0·417 |

| Tumour size (cm) | 3·0 (0·2–8·0) | 3·7 (0·5–12·0) | 3·5 (2·3–6·7) | < 0·001§ | 0·623§ |

| Serosal invasion | 23 (10·0) | 48 (20·7) | 14 (37) | < 0·001 | 0·028 |

| Retropancreatic tissue invasion | 193 (83·9) | 221 (95·3) | 38 (100) | < 0·001 | 0·372 |

| Distal bile duct invasion | 143 (62·2) | 146 (62·9) | 26 (68) | 0·761 | 0·514 |

| Duodenal invasion | 147 (63·9) | 136 (58·6) | 19 (50) | 0·201 | 0·319 |

| Extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion | 86 (37·4) | 138 (59·5) | 27 (71) | < 0·001 | 0·175 |

| pPV | 10 (4·3) | 84 (36·2) | 31 (82) | < 0·001 | < 0·001 |

| R1 resection status | 44 (19·1) | 79 (34·1) | 16 (42) | < 0·001 | 0·335 |

| Site of tumour‐positive margin | |||||

| Pancreatic cut end | 5 (2·2) | 18 (7·8) | 3 (8) | 0·019 | 1·000 |

| Bile duct cut end | 0 (0) | 1 (0·4) | 0 (0) | 0·561 | 1·000 |

| Dissected peripancreatic tissue | 39 (17·0) | 68 (29·3) | 16 (42) | < 0·001 | 0·114 |

| T category | < 0·001 | 0·226 | |||

| T1 | 29 (12·6) | 17 (7·3) | 0 (0) | ||

| T2 | 168 (73·0) | 147 (63·4) | 26 (68) | ||

| T3 | 33 (14·3) | 68 (29·3) | 12 (32) | ||

| T4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| N category | 0·028 | 0·490 | |||

| N0 | 73 (31·7) | 57 (24·6) | 7 (18) | ||

| N1 | 91 (39·6) | 82 (35·3) | 12 (32) | ||

| N2 | 66 (28·7) | 93 (40·1) | 19 (50) | ||

| UICC stage | 0·090 | 0·703 | |||

| IA | 18 (7·8) | 10 (4·3) | 0 (0) | ||

| IB | 49 (21·3) | 40 (17·2) | 6 (16) | ||

| IIA | 6 (2·6) | 7 (3·0) | 1 (3) | ||

| IIB | 89 (38·7) | 79 (34·1) | 11 (29) | ||

| III | 52 (22·6) | 65 (28·0) | 13 (34) | ||

| IV | 16 (7·0) | 31 (13·4) | 7 (18) | ||

| Morbidity | 0·005 | 0·954 | |||

| None | 78 (33·9) | 116 (50·0) | 20 (53) | ||

| Minor | 133 (57·8) | 96 (41·4) | 15 (39) | ||

| Major | 19 (8·3) | 20 (8·6) | 3 (8) | ||

| Pancreatic fistula | < 0·001 | 0·860 | |||

| None | 128 (55·7) | 184 (79·3) | 31 (82) | ||

| Grade A | 20 (8·7) | 10 (4·3) | 2 (5) | ||

| Grade B | 82 (35·7) | 38 (16·4) | 5 (13) | ||

| Grade C | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range). CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA, carbohydrate antigen; PVR, portal/superior mesenteric vein resection; pPV, pathological portal/superior mesenteric vein invasion.

Comparison of the three groups (χ2 test, except

Kruskal–Wallis test);

comparison of groups 2 and 3 (χ2 or Fisher's exact test, except

Mann–Whitney U test).

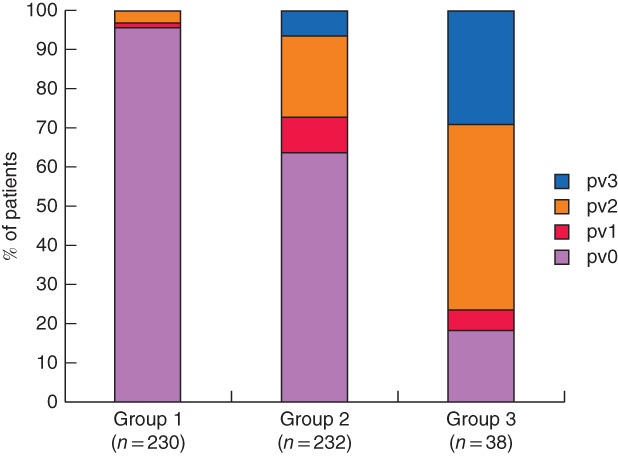

Regarding pPV, pv0 accounted for 63·8 per cent (148 of 232) of the patients in group 2, whereas the proportion was only 18 per cent (7 of 38) in group 3 (P < 0·001). The positive predictive value of tumour contact with PV or of tumour contact with PV greater than 180° in predicting positive pPV was 42·6 per cent (115 of 270) and 82 per cent (31 of 38) respectively. Even among patients who underwent PVR, the proportion with pv0 in group 2 was 50·6 per cent (86 of 170), significantly higher than that in group 3 (5 of 36, 14 per cent; P < 0·001). Comparisons of extent of pPV are shown in Fig. 1. The differences were significant between the three groups (P < 0·001) and between groups 2 and 3 (P < 0·001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of pathological portal vein invasion in the three study groups. P < 0·001 (group 1 versus group 2 versus group 3, Kruskal–Wallis test), P < 0·001 (group 2 versus group 3, Mann–Whitney U test)

Survival

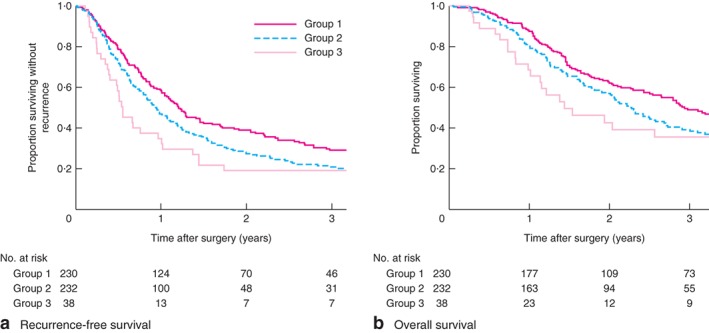

Fig. 2 shows RFS and OS according to study group. Patients in group 1 had a significantly better RFS (median 14·4 months; 5‐year survival rate 23·2 per cent) than those in groups 2 (median 11·2 months; 5‐year survival rate 11·4 per cent; P = 0·008) and 3 (median 6·5 months; 5‐year survival rate 16 per cent; P = 0·016), whereas RFS was not statistically different between groups 2 and 3 (P = 0·282). There was a significant difference in OS between groups 1 and 2 (median 35·2 versus 26·9 months respectively; 5‐year survival rate 34·5 versus 22·9 per cent, P = 0·018). The difference between groups 2 and 3 (median 17·2 months; 5‐year OS rate 31 per cent) was not significant (P = 0·750).

Figure 2.

Postoperative recurrence‐free and overall survival in the three study groups. a Recurrence‐free and b overall survival. a P = 0·008 (group 1 versus group 2), P = 0·016 (group 1 versus group 3), P = 0·282 (group 2 versus group 3); b P = 0·018 (group 1 versus group 2), P = 0·172 (group 1 versus group 3), P = 0·750 (group 2 versus group 3) (log rank test)

According to extent of pPV, median RFS of patients with pv0 was 13·9 months, better than that of patients with pv1 (11·3 months; P = 0·014), pv2 (10·0 months; P = 0·005) and pv3 (6·1 months; P = 0·070). RFS in patients with pv1, pv2 and pv3 was not significantly different (P = 0·906). Similarly, median OS of patients with pv0 was 33·4 months, significantly better than that of those with pv1 (28·9 months; P = 0·006), pv2 (27·3 months; P = 0·033) and pv3 (16·5 months; P = 0·025). OS was not significantly different between pv1, pv2 and pv3 groups (P = 0·578).

Table 2 shows univariable and multivariable analyses of prognostic predictors. Although PV invasion recognized both by preoperative CT and by pathological examination was associated with worse OS in univariable analysis, none was an independent prognostic factor in multivariable analysis.

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of overall survival

| Survival | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median (months) | 5‐year (%) | Hazard ratio | P | Hazard ratio | P | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| ≥ 70 | 182 | 27·4 | 31·0 | 0·94 (0·74, 1·21) | 0·644 | ||

| < 70 | 318 | 30·0 | 28·2 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Sex | |||||||

| M | 292 | 30·4 | 30·1 | 0·96 (0·76, 1·22) | 0·758 | ||

| F | 208 | 27·6 | 27·5 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| PV invasion by CT | |||||||

| Yes | 270 | 26·6 | 24·3 | 1·33 (1·06, 1·68) | 0·015 | ||

| No | 230 | 35·2 | 34·5 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| CEA (ng/ml) | |||||||

| > 5 | 104 | 22·4 | 19·5 | 1·31 (1·00, 1·73) | 0·052 | ||

| ≤ 5 | 396 | 32·5 | 31·7 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| CA19‐9 (units/ml) | |||||||

| > 200 | 204 | 24·4 | 21·9 | 1·40 (1·11, 1·76) | 0·005 | 1·30 (1·03, 1·63) | 0·029 |

| ≤ 200 | 296 | 34·0 | 34·2 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Blood loss (ml) | |||||||

| > 1000 | 206 | 21·0 | 22·7 | 1·58 (1·25, 1·98) | < 0·001 | ||

| ≤ 1000 | 294 | 36·0 | 33·7 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||||

| No | 272 | 20·7 | 22·5 | 1·79 (1·41, 2·29) | < 0·001 | 1·98 (1·56, 2·53) | < 0·001 |

| Yes | 228 | 42·7 | 37·9 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Tumour size (cm) | |||||||

| > 4·0 | 113 | 21·2 | 19·4 | 1·63 (1·26, 2·10) | < 0·001 | ||

| ≤ 4·0 | 387 | 33·5 | 31·9 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Serosal invasion | |||||||

| Yes | 85 | 21·2 | 21·4 | 1·52 (1·15, 2·00) | 0·003 | ||

| No | 415 | 33·4 | 30·8 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Retropancreatic tissue invasion | |||||||

| Yes | 452 | 27·6 | 26·4 | 2·51 (1·53, 4·09) | < 0·001 | ||

| No | 48 | 135·4 | 54·3 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Distal bile duct invasion | |||||||

| Yes | 315 | 25·1 | 22·8 | 1·57 (1·23, 2·02) | < 0·001 | ||

| No | 185 | 43·0 | 40·3 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Duodenal invasion | |||||||

| Yes | 302 | 26·6 | 25·5 | 1·31 (1·03, 1·66) | 0·029 | ||

| No | 198 | 34·5 | 35·0 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion | |||||||

| Yes | 251 | 21·2 | 21·3 | 1·74 (1·38, 2·19) | < 0·001 | 1·37 (1·07, 1·76) | 0·013 |

| No | 249 | 41·5 | 37·0 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ‐ | |

| pPV | |||||||

| Yes | 125 | 24·4 | 20·9 | 1·53 (1·20, 1·97) | 0·001 | ||

| No | 375 | 33·4 | 32·1 | 1·00 (reference) | |||

| Nodal metastases | |||||||

| Yes | 363 | 24·7 | 20·6 | 2·24 (1·67, 3·00) | < 0·001 | 1·92 (1·42, 2·58) | < 0·001 |

| No | 137 | 68·8 | 52·0 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Resection status | |||||||

| R1 | 139 | 19·0 | 15·0 | 1·94 (1·51, 2·49) | < 0·001 | 1·57 (1·21, 2·03) | 0·001 |

| R0 | 361 | 34·8 | 33·9 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals. PV, portal/superior mesenteric vein; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA, carbohydrate antigen; pPV, pathological PV invasion.

Comparison between patients with PVR(−)pv0 and matched patients with PVR(+)pv0

PVR was not performed in 64 of the 270 patients in groups 2 and 3 (PVR(−)pv0). Of the remaining 206 patients who did have PVR, 91 did not have pathologically identified PV invasion. Preoperative CA19‐9 and distribution of UICC T category were not comparable between these two groups of patients (64 with no PVR and 91 with PVR: median CA19‐9 concentration 66·0 versus 162·0 units/ml, P = 0·024; T1, T2 and T3 status in 10, 37 and 17 patients respectively versus 5, 64 and 22, P = 0·083). Thus, 64 of the 91 patients with PVR were selected as matched patients (PVR(+)pv0) for those with PVR(−)pv0 status.

Preoperative CA19‐9 concentration, R status and pathological stage were comparable between these two groups. Postoperative pancreatic fistulas developed significantly more frequently in the PVR(−)pv0 group (Table 3). Among patients with a positive margin in peripancreatic tissue, the positive margin site did not differ between the two groups (PVR(−)pv0 versus PVR(+)pv0: pancreatic head plexus, 8 of 19 (42 per cent) versus 7 of 13 (54 per cent) respectively; retropancreatic fat tissue, 6 of 19 (32 per cent) versus 1 of 13 (8 per cent); PV sulcus or around the resected PV, 4 of 19 (21 per cent) versus 4 of 13 (31 per cent); other site, 1 of 19 (5 per cent) versus 1 of 13 (8 per cent); P = 0·457).

Table 3.

Perioperative variables in patients without invasion of the portal vein who did not undergo resection and matched patients who underwent resection

| PVR(−)pv0 (n = 64) | PVR(+)pv0 (n = 64) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 68 (36–83) | 68 (43–89) | 0·329‡ |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 36 : 28 | 32 : 32 | 0·479 |

| CEA (ng/ml)* | 2·4 (0·6–10·6) | 2·8 (0·6–49·4) | 0·031‡ |

| CA19‐9 (units/ml)* | 66 (0–3843) | 134 (0–4644) | 0·122‡ |

| Duration of surgery (min)* | 462 (300–881) | 508 (300–760) | 0·188‡ |

| Blood loss (m) | 621 (142–4322) | 728 (217–2960) | 0·292‡ |

| Group | 0·680 | ||

| B | 62 (97) | 60 (94) | |

| C | 2 (3) | 4 (6) | |

| Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy | 29 (45) | 44 (69) | 0·007 |

| Tumour size (cm)* | 3·5 (0·5–11·3) | 3·4 (1·0–12·0) | 0·716‡ |

| Serosal invasion | 11 (17) | 11 (17) | 1·000 |

| Retropancreatic tissue invasion | 56 (88) | 61 (95) | 0·206 |

| Distal bile duct invasion | 34 (53) | 41 (64) | 0·209 |

| Duodenal invasion | 32 (50) | 35 (55) | 0·595 |

| Extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion | 28 (44) | 36 (56) | 0·157 |

| R1 resection status | 22 (34) | 17 (27) | 0·337 |

| Site of tumour‐positive margin | |||

| Pancreatic cut end | 4 (6) | 5 (8) | 1·000 |

| Bile duct cut end | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1·000 |

| Dissected peripancreatic tissue | 19 (30) | 13 (20) | 0·221 |

| T category | 0·156 | ||

| T1 | 10 (16) | 5 (8) | |

| T2 | 37 (58) | 47 (73) | |

| T3 | 17 (27) | 12 (19) | |

| T4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| N category | 0·851 | ||

| N0 | 22 (34) | 21 (33) | |

| N1 | 21 (33) | 24 (38) | |

| N2 | 21 (33) | 19 (30) | |

| UICC stage | 0·659 | ||

| IA | 6 (9) | 4 (6) | |

| IB | 13 (20) | 15 (23) | |

| IIA | 3 (5) | 2 (3) | |

| IIB | 18 (28) | 24 (38) | |

| III | 14 (22) | 14 (22) | |

| IV | 10 (16) | 5 (8) | |

| Morbidity | 0·339 | ||

| None | 32 (50) | 39 (61) | |

| Minor | 29 (45) | 24 (38) | |

| Major | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| Pancreatic fistula | 0·011 | ||

| None | 45 (70) | 57 (89) | |

| Grade A | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | |

| Grade B | 18 (28) | 5 (8) | |

| Grade C | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range). PVR(−)pv0, no portal/superior mesenteric vein (PV) resection and no pathological PV invasion; PVR(+)pv0, PV resection and no pathological PV invasion; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA, carbohydrate antigen.

χ2 or Fisher's exact test, except

Mann–Whitney U test.

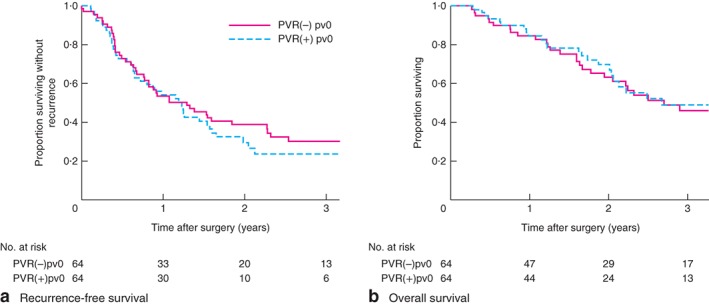

Both median RFS (PVR(−)pv0 versus PVR(+)pv0: 15·5 versus 14·7 months respectively; P = 0·557) and OS (32·4 versus 32·1 months; P = 0·780) were similar between the two groups (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Recurrence‐free and overall survival in patients with no invasion who did not undergo resection and matched patients who did have resection. a Recurrence‐free and b overall survival in patients with no pathologically identified invasion of the portal/superior mesenteric vein (PV) who did not have PV resection (PVR(−)pv0) and matched patients who did undergo PV resection (PVR(+)pv0). a P = 0·557, b P = 0·780 (log rank test)

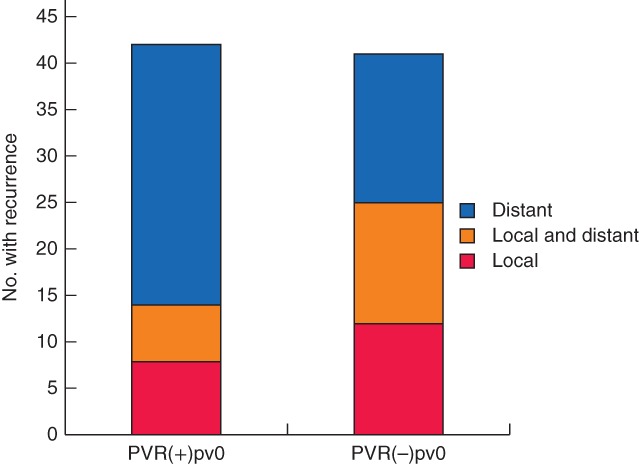

Tumour recurrence was recognized in 41 (64 per cent) and 42 patients (66 per cent) in PVR(−)pv0 and PVR(+)pv0 groups respectively (P = 0·853). The sites of initial recurrence differed between the two groups (Fig. 4), the proportion with local recurrence being significantly higher in the PVR(−)pv0 group (25 of 41 (61 per cent) versus 14 of 42 (33 per cent) in the PVR(+)pv0 group; P = 0·012).

Figure 4.

Comparison of sites of initial tumour recurrence in patients with no invasion who did not undergo resection and matched patients who did have resection. VR(−)pv0, no portal/superior mesenteric vein (PV) resection and no pathological PV invasion; PVR(+)pv0, PV resection and no pathological PV invasion. P = 0·036 (Mann–Whitney U test)

Discussion

This study has shown the inaccuracy of CT in predicting PV invasion. If there is no pPV, PVR does not result in better survival. Multivariable analysis suggested that other tumour factors or adjuvant chemotherapy rather than PV invasion were associated with postoperative prognosis.

The low accuracy of CT in the prediction of pPV in the present study was concordant with previous studies2 10, 12. Nakao and colleagues2 stratified their patients' postoperative prognosis by the radiological but not the pathological classification. The present results are also in agreement with the study of Ohgi and co‐workers10, who reported similar postoperative survival in patients with resectable and those with BR‐PV PDAC according to CT findings, with median survival of 20·7 and 18·6 months respectively. Hoshimoto et al.14 also showed comparable survival in patients with BR‐PV and those with resectable PDAC. All three studies, including the present one, that showed comparable survival included only 21–39 patients with borderline resectable PDAC. In contrast, a multi‐institutional study3 of 114 and 145 patients with resectable and BR‐PV PDAC respectively found significantly better survival in the former group (median 22·0 versus 17·4 months; P = 0·024). The present results indicate that the presence, but not the extent, of PV involvement is associated with a higher R1 resection rate and worse prognosis.

Whether it is feasible to perform PVR only when intraoperative findings suggest PV invasion has rarely been addressed. Most studies failed to describe clearly their strategy on this point. Ohgi and colleagues10 performed PVR only when it was judged to be necessary during surgery. They did not, however, specifically determine the prognosis of patients who did not undergo PVR as a result of dissection around the PV despite CT findings suggestive of PV invasion. Turrini et al.15 were the first to compare matched groups of pv0 patients who underwent PD with and without PVR. They showed significantly better survival in the patients who had PVR; group size was small, with only 19 patients in each group15. These authors suggested that dissection of PV from tumour increases the incidence of non‐curative resection. In the present series, the sites of positive excision margins were comparable between PVR(−)pv0 and PVR(+)pv0 groups. Similar to the previous report21, the most common site of positive margins was around the pancreatic head neural plexus and not around the PV bed. Studies have shown no difference in the proportion of local and distant recurrence between patients with R0 and R1 resection21, or between patients with and without pPV5. The present results suggest that extensive surgical resection with PVR does not compensate for the aggressive biology of PDAC, especially in the era of adjuvant chemotherapy.

This study had several limitations including its retrospective design. Matched‐pair analyses should have corrected for some selection bias. Second, the PVR(−)pv0 group might potentially include patients with pPV, because pv0 can be confirmed only following PVR. The R1 rate, the sites of resection margin positivity and postoperative prognosis were, however, comparable between the two groups. The authors therefore recommend dissection around the PV when easily possible, and no hesitation in performing PVR when the dissection is difficult.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank T. Reynolds from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control (number 16ck0106211s0101) of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Presented to the 13th World Congress of the International Hepato‐Pancreato‐Biliary Association, Geneva, Switzerland, September 2018; published in abstract form as HPB 2018; 20: S540–S541

Funding information

Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, 16ck0106211s0101

References

- 1. Wang J, Estrella JS, Peng L, Rashid A, Varadhachary GR, Wang H et al Histologic tumor involvement of superior mesenteric vein/portal vein predicts poor prognosis in patients with stage II pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Cancer 2012; 118: 3801–3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakao A, Kanzaki A, Fujii T, Kodera Y, Yamada S, Sugimoto H et al Correlation between radiographic classification and pathological grade of portal vein wall invasion in pancreatic head cancer. Ann Surg 2012; 255: 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murakami Y, Satoi S, Sho M, Motoi F, Matsumoto I, Kawai M et al National comprehensive cancer network resectability status for pancreatic carcinoma predicts overall survival. World J Surg 2015; 39: 2306–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramacciato G, Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Pinna AD, Ravaioli M, Jovine E et al Pancreatectomy with mesenteric and portal vein resection for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: multicenter study of 406 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2016; 23: 2028–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mierke F, Hempel S, Distler M, Aust DE, Saeger HD, Weitz J et al Impact of portal vein involvement from pancreatic cancer on metastatic pattern after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol 2016; 23(Suppl 5): 730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Addeo P, Velten M, Averous G, Faitot F, Nguimpi‐Tambou M, Nappo G et al Prognostic value of venous invasion in resected T3 pancreatic adenocarcinoma: depth of invasion matters. Surgery 2017; 162: 264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Porembka MR, Hawkins WG, Linehan DC, Gao F, Ma C, Brunt EM et al Radiologic and intraoperative detection of need for mesenteric vein resection in patients with adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. HPB (Oxford) 2011; 13: 633–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ravikumar R, Sabin C, Abu Hilal M, Bramhall S, White S, Wigmore S et al; UK Vascular Resection in Pancreatic Cancer Study Group . Portal vein resection in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a United Kingdom multicenter study. J Am Coll Surg 2014; 218: 401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang F, Gill AJ, Neale M, Puttaswamy V, Gananadha S, Pavlakis N et al Adverse tumor biology associated with mesenterico‐portal vein resection influences survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2014; 21: 1937–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ohgi K, Yamamoto Y, Sugiura T, Okamura Y, Ito T, Ashida R et al Is pancreatic head cancer with portal venous involvement really borderline resectable? Appraisal of an upfront surgery series. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 2752–2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Guidelines Version 3.2017. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma 2017; 2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf [accessed 7 March 2018].

- 12. Tran Cao HS, Balachandran A, Wang H, Nogueras‐González GM, Bailey CE, Lee JE et al Radiographic tumor–vein interface as a predictor of intraoperative, pathologic, and oncologic outcomes in resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 18: 269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chun YS, Milestone BN, Watson JC, Cohen SJ, Burtness B, Engstrom PF et al Defining venous involvement in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17: 2832–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoshimoto S, Hishinuma S, Shirakawa H, Tomikawa M, Ozawa I, Wakamatsu S et al Reassessment of the clinical significance of portal‐superior mesenteric vein invasion in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017; 43: 1068–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turrini O, Ewald J, Barbier L, Mokart D, Blache JL, Delpero JR. Should the portal vein be routinely resected during pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma? Ann Surg 2013; 257: 726–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ueno H, Kosuge T, Matsuyama Y, Yamamoto J, Nakao A, Egawa S et al A randomised phase III trial comparing gemcitabine with surgery‐only in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: Japanese Study Group of Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Br J Cancer 2009; 101: 908–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Uesaka K, Boku N, Fukutomi A, Okamura Y, Konishi M, Matsumoto I et al; JASPAC 01 Study Group . Adjuvant chemotherapy of S‐1 versus gemcitabine for resected pancreatic cancer: a phase 3, open‐label, randomised, non‐inferiority trial (JASPAC 01). Lancet 2016; 388: 248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD et al The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five‐year experience. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M et al; International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) . The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 2017; 161: 584–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. (eds). UICC: TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors (8th edn). John Wiley: Chichester, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raut CP, Tseng JF, Sun CC, Wang H, Wolff RA, Crane CH et al Impact of resection status on pattern of failure and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2007; 246: 52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]