Abstract

Background

The advent of effective adjuvant therapies for patients with resected melanoma has highlighted the need to stratify patients based on risk of relapse given the cost and toxicities associated with treatment. Here we assessed circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) to predict and monitor relapse in resected stage III melanoma.

Patients and methods

Somatic mutations were identified in 99/133 (74%) patients through tumor tissue sequencing. Personalized droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assays were used to detect known mutations in 315 prospectively collected plasma samples from mutation-positive patients. External validation was performed in a prospective independent cohort (n = 29).

Results

ctDNA was detected in 37 of 99 (37%) individuals. In 81 patients who did not receive adjuvant therapy, 90% of patients with ctDNA detected at baseline and 100% of patients with ctDNA detected at the postoperative timepoint relapsed at a median follow up of 20 months. ctDNA detection predicted patients at high risk of relapse at baseline [relapse-free survival (RFS) hazard ratio (HR) 2.9; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.5–5.6; P = 0.002] and postoperatively (HR 10; 95% CI 4.3–24; P < 0.001). ctDNA detection at baseline [HR 2.9; 95% CI 1.3–5.7; P = 0.003 and postoperatively (HR 11; 95% CI 4.3–27; P < 0.001] was also associated with inferior distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS). These findings were validated in the independent cohort. ctDNA detection remained an independent predictor of RFS and DMFS in multivariate analyses after adjustment for disease stage and BRAF mutation status.

Conclusion

Baseline and postoperative ctDNA detection in two independent prospective cohorts identified stage III melanoma patients at highest risk of relapse and has potential to inform adjuvant therapy decisions.

Keywords: circulating tumor DNA, melanoma, adjuvant therapy

Key Message

ctDNA detection pre-surgery and postoperatively can identify patients with melanoma at highest risk of relapse and serial ctDNA analysis may allow real-time surveillance of disease recurrence. Future efforts to enroll patients onto adjuvant clinical trials based on the detection of ctDNA are warranted to establish the clinical utility of ctDNA analysis in this setting.

Introduction

Individuals with stage III cutaneous melanoma represent a heterogeneous population of patients. Resection of the primary melanoma with regional lymph node sampling and/or completion lymphadenectomy is the mainstay of treatment [1]. The 5-year survival rates range from 93% in stage IIIA disease, through to 32% for stage IIID [2–4]. Given the high risk of locoregional and distant metastatic recurrence, many centers have adopted routine imaging surveillance following surgical resection, however, guidelines for the optimal imaging modality and frequency are currently lacking [4, 5]

The evolving use of adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies are rapidly changing the treatment paradigm in stage III disease and have resulted in significantly lower rates of relapse and improved overall survival (OS) following surgical resection [6–10]. Despite the unprecedented success of these therapies, the significant cost and toxicities associated with treatment has highlighted the need for improved risk stratification beyond clinicopathological parameters to guide the delivery of adjuvant therapy to those most likely to recur, whilst avoiding treatment in patients cured with surgery alone.

The use of ctDNA is emerging as an important minimally invasive biomarker for molecular profiling and disease monitoring across a range of malignancies, including melanoma [11] In early-stage breast, colorectal and lung cancers, initial studies have demonstrated that ctDNA analysis can be used to detect minimal residual disease (MRD) post-surgery and identify recurrence before disease becomes apparent on radiological assessment [12–16]. In high-risk stage III melanoma, ctDNA analysis may have a role in predicting patients most at risk of relapse and allow monitoring of MRD to guide optimal patient selection and duration of adjuvant therapy. Here, we applied ctDNA analysis to prospectively collected plasma samples from patients with resected stage III melanoma to assess if this approach could identify patients at high risk of relapse.

Patients and methods

Primary patient cohort

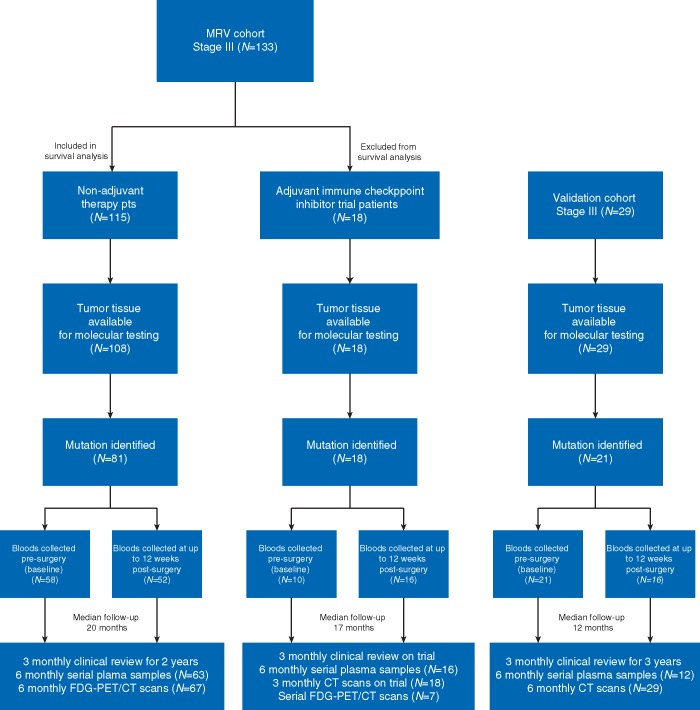

Between March 2011 and December 2016, 133 patients with newly diagnosed stage III resected cutaneous melanoma were enrolled into the Melanoma Research Victoria (MRV) study (Figure 1). Institutional ethics approval was obtained (project number 07/38) and patients consented to collection of archival tumor tissue and longitudinal monitoring with serial plasma and F-18-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography combined with computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) during routine follow up. Clinical relapse was determined via imaging and/or clinical examination, and, if equivocal, was confirmed via biopsy (supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram of patients included in the study.

Validation cohort

An independent cohort of 29 patients with resected stage III melanoma treated at The Christie NHS Foundation Trust in Manchester, United Kingdom were recruited to a prospective study with serial plasma and CT imaging during routine follow up. The study was approved by the MCRC Biobank Access Committee (13_RIMA_01). All blood and tissue samples collected and utilized for the purpose of the study were obtained with written informed consent (supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Mutational analysis of tumor and circulating tumor DNA

The mutational status of tumor samples from the MRV cohort was determined using targeted amplicon-based next-generation sequencing or high-resolution melting analysis/Sanger sequencing/pyrosequencing (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) [17] In patients with BRAF/NRAS wild-type disease, a single targeted amplicon sequencing approach or ddPCR was used to identify TERT promoter mutations, when remaining tumor-derived DNA was available [11]. The mutational status of tumor samples from the validation cohort was determined via pyrosequencing (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Cell-free DNA was isolated from up to 5 ml of plasma and ddPCR was performed using the Bio-Rad QX200 ddPCR system. ctDNA was defined as detectable if there was ≥1 copy of mutant DNA detected in both duplicate reactions. Uniform criteria were applied to select mutations for ctDNA monitoring (supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Statistical analysis

Associations between baseline and postoperative ctDNA status and clinicopathological characteristics were performed using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables.

RFS and DMFS were measured from the date of surgery to the documented date of first clinical relapse (local, regional, or distant metastasis) or death due to melanoma and were censored at last follow up. OS was measured from the date of surgery to date of death and was censored at last follow up. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate univariable survival estimates for RFS, DMFS and OS in patients with detectable versus undetectable ctDNA. A univariate Cox proportional hazard model was used to obtain HRs and 95% CI for ctDNA and clinicopathological variables. Multivariate Cox regression models incorporating BRAF mutation status, disease stage and ctDNA detection were used to test the independent prognostic value of predicting relapse. A time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to assess the time-dependent accuracy of postoperative ctDNA in predicting relapse [18]. Discrimination was assessed by the area under the ROC curve (c-index). Statistical analyses were performed with R version 3.4.4 packages ‘survival’, ‘survivalROC’, ‘pROC’ and GraphPad Prism version c7.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.), where P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and ctDNA status

One hundred and thirty-three patients with stage III melanoma as defined by the AJCC classification 8th edition [3] were enrolled into the MRV study (Figure 1, supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The median age at diagnosis was 57 years (range: 22–93 years), and 66% were male. Overall, 14 patients (11%) had stage IIIA, 42 (31%) had stage IIIB, 72 (54%) had stage IIIC and 5 (4%) had stage IIID disease. Across the cohort, 115 (86%) patients did not receive adjuvant therapy. Eighteen (14%) patients participated on an adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor clinical trial [7, 9]

Somatic mutation testing was performed in 126/133 individuals due to availability of primary tumor tissue and identified at least one somatic mutation in 99/126 (79%) patients. BRAF and NRAS mutations were detected in 53/99 (54%) and 31/99 (31%) patients, respectively. Alternative mutations in the TERT promoter, TP53 and KIT were identified in an additional 15/99 (15%) patients (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

ctDNA analysis was performed in all 99 patients where a somatic mutation had been identified using individualized ddPCR assays (supplementary Tables S3 and S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Of the 99 patients, 68 had a plasma sample available at baseline, 68 had a postoperative plasma sample and 79 had serial plasma samples collected during follow up (Figure 1). ctDNA was detected in 37/99 (37%) individuals across the cohort; this included 24/68 (35%) at baseline, 16/68 (24%) postoperatively and 21/79 (27%) with detectable ctDNA through serial sampling (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The median ctDNA levels at baseline were 9 copies/ml (range: 3–555) and baseline ctDNA levels increased with disease stage (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The clinicopathological characteristics of the cohort, according to baseline and postoperative ctDNA status are presented in Table 1. The presence of ctDNA at baseline was significantly associated with Breslow thickness and disease stage, while the presence of ctDNA postoperatively was significantly associated with ulceration of the primary tumor. Moreover, there was a significant association between the presence of ctDNA at baseline and detectable ctDNA at the postoperative timepoint (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients in the MRV cohort according to baseline and postoperative ctDNA status

| Characteristics | ctDNA baseline |

ctDNA postoperative |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undetected N (%) | Detected N (%) | P | Total N (%) | Undetected N (%) | Detected N (%) | P | Total N (%) | |

| Age | ||||||||

| <70 years | 35 (67) | 17 (33) | 0.55 | 52 (76) | 35 (73) | 13 (27) | 0.74 | 52 (76) |

| ≥70 years | 9 (56) | 7 (44) | 16 (24) | 9 (75) | 3 (25) | 16 (24) | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 29 (60) | 19 (40) | 0.28 | 48 (71) | 35 (78) | 10 (22) | 0.77 | 45 (66) |

| Female | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | 20 (29) | 17 (74) | 6 (26) | 23 (34) | ||

| AJCC substage | ||||||||

| IIIA | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.02 | 7 (10) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.06 | 8 (11) |

| IIIB | 16 (70) | 7 (30) | 23 (34) | 21 (88) | 3 (12) | 24 (32) | ||

| IIIC and IIID | 21 (55) | 17 (45) | 38 (56) | 23 (62) | 14 (38) | 37 (49) | ||

| Breslow thickness | ||||||||

| ≤2.0 mm | 23 (79) | 6 (21) | 0.046 | 29 (46) | 27 (87) | 4 (13) | 0.09 | 31 (53) |

| >2.0-4.0 mm | 9 (69) | 4 (31) | 13 (21) | 7 (88) | 1 (12) | 8 (14) | ||

| >4.0 mm | 11 (52) | 10 (48) | 21 (33) | 11 (58) | 8 (42) | 19 (33) | ||

| Ulceration | ||||||||

| Absent | 28 (74) | 10 (26) | 0.39 | 38 (62) | 31 (89) | 4 (11) | 0.02 | 35 (62) |

| Present | 14 (61) | 9 (39) | 23 (38) | 13 (62) | 8 (38) | 21 (38) | ||

| Nodal status | ||||||||

| N1a, N2a | 21 (84) | 4 (16) | 0.05 | 25 (36) | 18 (90) | 2 (10) | 0.18 | 20 (29) |

| ≥N1b–N3c | 23 (52) | 21 (48) | 44 (64) | 34 (71) | 14 (29) | 48 (71) | ||

| Mutation status | ||||||||

| BRAF | 28 (74) | 10 (26) | 0.12 | 38 (44) | 27 (75) | 9 (25) | 0.78 | 36 (42) |

| NRAS | 13 (62) | 8 (38) | 0.79 | 21 (24) | 21 (78) | 6 (22) | 1.00 | 27 (31) |

| TERT | 15 (54) | 13 (46) | 0.13 | 28 (32) | 17 (74) | 6 (26) | 0.77 | 23 (27) |

| Adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor trial | ||||||||

| Yes | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | 1.00 | 10 (15) | 13 (81) | 3 (19) | 0.74 | 16 (24) |

| No | 37 (64) | 21 (36) | 58 (85) | 39 (75) | 13 (25) | 52 (76) | ||

P values were obtained using Fisher’s exact test for categorical factors. P values that are significant are in bold.

Abbreviations: MRV, Melanoma Research Victoria; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA.

At a median follow up of 18 months (range: 2–58 months), 53 of 99 (54%) had relapsed (n = 5, 15, 29 and 4 for IIIA, IIIB, IIIC and IIID, respectively). Of the 53 patients who relapsed, none had participated on adjuvant therapy trials. A total of 10 patients presented with locoregional recurrence whereas 43 had distant metastatic disease (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Detection of ctDNA and prediction of relapse

To avoid the confounding effect of adjuvant therapy, we assessed the potential of ctDNA analysis to predict relapse from plasma collected at baseline and in the immediate postoperative period (median 2 weeks post-surgery) in 81 of 99 patients who did not receive adjuvant therapy and had a mutation identified. Of these patients, 58/81 had baseline plasma and 52/81 had a postoperative sample available for analysis (Figure 1).

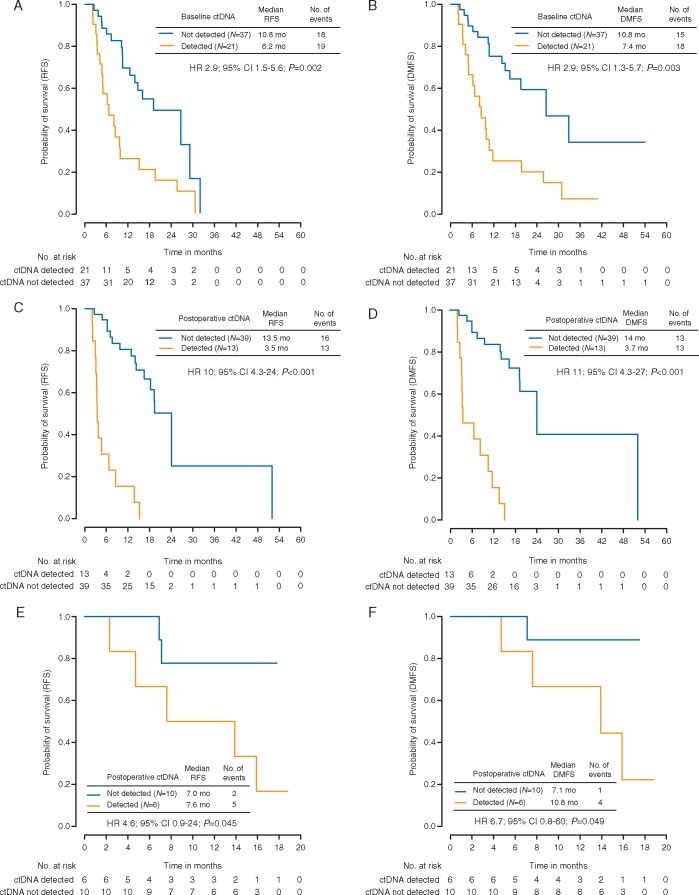

ctDNA was detected at baseline in 21 of 58 (36%) patients. The detection of ctDNA at baseline was predictive of relapse (RFS HR 2.9; 95% CI 1.5–5.6; P = 0.002) (Figure 2A) with 19/21 patients (90%) relapsing during the follow-up period (median 6.2 months to relapse). In contrast, disease recurrence was documented in 18 of 37 (49%) patients with undetectable ctDNA at baseline (median 10.8 months to relapse). Of the two patients with detectable ctDNA at baseline who did not relapse, one had ctDNA levels that became undetectable postoperatively, and the other had a detectable TERT promoter mutation on serial ctDNA samples and was subsequently diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The majority of patients with detectable ctDNA who relapsed demonstrated distant metastatic disease rather than locoregional relapse (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). In keeping with this finding, the detection of ctDNA at baseline was associated with reduced DMFS [HR 2.9; 95% CI 1.3–5.7; P = 0.003 (Figure 2B) with a median of 7.4 months versus 10.8 months to distant metastatic relapse in patients with detectable versus undetectable ctDNA. Higher levels of ctDNA at baseline were associated with relapse within 6 months of diagnosis (P < 0.01; supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Overall, the c-index for RFS based on baseline ctDNA detection was 0.71 (95% CI 0.60–0.82) and for DMFS was 0.71 (95% CI 0.60–0.82).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of (A) RFS and (B) DMFS in non-adjuvant-treated patients stratified by baseline ctDNA detection. Kaplan–Meier analysis of (C) RFS and (D) DMFS in non-adjuvant-treated patients stratified by postoperative ctDNA detection. Kaplan–Meier analysis of (E) RFS and (F) DMFS stratified by postoperative ctDNA detection in a validation cohort of stage III melanoma patients. RFS, relapse-free survival; DMFS, distant metastasis-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA.

We next examined the ability of ctDNA to predict relapse from a single postoperative time point. ctDNA was detected postoperatively in 13 of 52 (25%) patients. The detection of ctDNA at the postoperative timepoint was a stronger predictor of relapse, compared to the baseline timepoint (RFS HR 10; 95% CI 4.3–24; P < 0.001) (Figure 2C). All patients with detectable ctDNA postoperatively relapsed during the follow-up period (median 3.5 months to relapse), in contrast to 16 of 39 (41%) patients with undetectable ctDNA at this timepoint (median 13.5 months to relapse). Detectable ctDNA at the postoperative timepoint was strongly associated with inferior DMFS (HR 11; 95% CI 4.3–27; P < 0.001) (Figure 2D) with a median of 3.7 months versus 14 months to distant metastatic relapse in patients with detectable versus undetectable ctDNA. Higher ctDNA levels at the postoperative timepoint showed a trend toward predicting relapse within 6 months of diagnosis (P = 0.07; supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The c-index for RFS based on postoperative ctDNA detection was 0.75 (95% CI 0.65–0.85) and for DMFS was 0.77 (95% CI 0.68–0.85). The time-dependent accuracy of postoperative ctDNA in predicting clinical relapse between 6 and 30 months following resection was also assessed through a time-dependent ROC analysis. The sensitivity and specificity of postoperative ctDNA in predicting relapse at 12 months were 55% and 94%, respectively (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online).

In addition to ctDNA status, other clinicopathological variables significantly associated with RFS and/or DMFS in univariate analysis were ulceration, nodal status and BRAF mutation status (Table 2). After multivariate adjustment for disease stage and BRAF mutation status, postoperative ctDNA detection remained an independent predictor of both RFS (HR 11; 95% CI 3.7–31.5; P < 0.001) and DMFS (HR 9; 95% CI 3.2–24.3; P < 0.001) (Table 3). In parallel to postoperative ctDNA, baseline ctDNA detection also remained a significant predictor of both RFS and DMFS in the multivariate models (supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 2.

Association between clinicopathological features, RFS, DMFS and OS by univariate cox proportional hazard regression analysis

| Variable | Total (N) | RFS |

DMFS |

OS |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events | HR | 95% CI | P | No. of events | HR | 95% CI | P | No. of events | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.10 | 0.32 | ||||||||||

| <70 | 81 | 49 | 1.00 | 44 | 1.00 | 7 | 1.00 | ||||||

| ≥70 | 34 | 19 | 1.00 | 0.59–1.70 | 12 | 0.60 | 0.31–1.10 | 5 | 1.80 | 0.56–4.30 | |||

| Sex | 0.22 | 0.45 | 0.42 | ||||||||||

| Male | 77 | 43 | 1.00 | 37 | 1.00 | 7 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Female | 38 | 25 | 0.73 | 0.45–1.20 | 19 | 0.81 | 0.46–1.40 | 5 | 0.62 | 0.20–2.00 | |||

| AJCC substage | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.88 | ||||||||||

| IIIA | 11 | 5 | 1.00 | 4 | 1.00 | 1 | 1.00 | ||||||

| IIIB | 32 | 18 | 2.00 | 0.67–5.80 | 14 | 1.70 | 0.54–5.20 | 4 | 1.70 | 0.19–16.0 | |||

| IIIC and IIID | 72 | 45 | 2.70 | 0.97–7.50 | 38 | 2.60 | 0.90–7.70 | 7 | 1.50 | 0.18–12.0 | |||

| Breslow thickness | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.18 | ||||||||||

| ≤2.0 mm | 41 | 24 | 1.00 | 20 | 1.00 | 6 | 1.00 | ||||||

| >2.0–4.0 mm | 21 | 10 | 0.77 | 0.37–1.60 | 8 | 0.82 | 0.36–1.90 | 0 | 0.14 | 0.00–1.20 | |||

| >4.0 mm | 39 | 26 | 1.40 | 0.78–2.40 | 22 | 1.40 | 0.73–2.50 | 4 | 0.62 | 0.17–2.20 | |||

| Ulceration | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.21 | ||||||||||

| Absent | 59 | 33 | 1.00 | 25 | 1.00 | 8 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Present | 38 | 24 | 1.50 | 0.89–2.60 | 22 | 1.80 | 1.00–3.30 | 2 | 0.39 | 0.08–1.80 | |||

| Nodal status | 0.004 | 0.08 | 0.35 | ||||||||||

| N1a, N2a | 38 | 18 | 1.00 | 16 | 1.00 | 3 | 1.00 | ||||||

| ≥N1b–N3c | 75 | 50 | 2.20 | 1.30–3.90 | 40 | 1.70 | 0.94–3.00 | 9 | 1.90 | 0.50–2.00 | |||

| BRAF mutation | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.67 | ||||||||||

| Absent | 66 | 35 | 1.00 | 27 | 1.00 | 8 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Present | 42 | 32 | 2.20 | 1.30–3.50 | 29 | 2.50 | 1.50–4.20 | 4 | 0.77 | 0.23–2.60 | |||

| NRAS mutation | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.24 | ||||||||||

| Absent | 85 | 57 | 1.00 | 47 | 1.00 | 9 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Present | 23 | 10 | 0.78 | 0.40–1.50 | 9 | 0.83 | 0.40–1.70 | 3 | 2.20 | 0.57–8.50 | |||

| TERT mutation | 0.79 | 0.22 | 0.23 | ||||||||||

| Absent | 69 | 40 | 1.00 | 31 | 1.00 | 5 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Present | 39 | 27 | 1.10 | 0.65–1.80 | 25 | 1.40 | 0.82–2.40 | 7 | 2.00 | 0.62–6.40 | |||

| Baseline ctDNA | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.22 | ||||||||||

| Undetected | 37 | 18 | 1.00 | 15 | 1.00 | 2 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Detected | 21 | 19 | 2.90 | 1.50–5.60 | 18 | 2.90 | 1.30–5.70 | 4 | 2.90 | 0.52–16.0 | |||

| Postoperative ctDNA | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.70 | ||||||||||

| Undetected | 39 | 16 | 1.00 | 13 | 1.00 | 3 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Detected | 13 | 13 | 10 | 4.30–24.0 | 13 | 11 | 4.30–27.0 | 2 | 1.40 | 0.23–9.00 | |||

Abbreviations: RFS, relapse-free survival; DMFS, distant metastasis-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer, ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA.

Table 3.

Multivariate cox proportional hazard regression analysis including BRAF mutation status, AJCC substage and postoperative ctDNA status for prediction of RFS and DMFS

| Variable | Total (N) | RFS |

DMFS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events | HR | 95% CI | P | No. of events | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| BRAF mutation | 0.58 | ||||||||

| Absent | 25 | 10 | 1.00 | 9 | 1.00 | ||||

| Present | 27 | 19 | 1.03 | 0.43–2.49 | 0.95 | 17 | 1.22 | 0.53–3.07 | |

| AJCC substage | |||||||||

| IIIA | 5 | 2 | 1.00 | 2 | 1.00 | ||||

| IIIB | 14 | 8 | 4.80 | 0.59–39.0 | 0.14 | 6 | 2.02 | 0.32–23.6 | 0.36 |

| IIIC and IIID | 33 | 19 | 3.02 | 0.34–26.8 | 0.32 | 18 | 2.12 | 0.35–25.7 | 0.31 |

| Postoperative ctDNA | |||||||||

| Undetected | 39 | 16 | 1.00 | 13 | 1.00 | ||||

| Detected | 13 | 13 | 11 | 3.7–31.5 | <0.001 | 13 | 9 | 3.2–24.3 | <0.001 |

RFS: C-index (95% CI) = 0.80 (0.74–0.86); C-index (95% CI) excluding ctDNA = 0.65 (0.61–0.69). DMFS: C-index (95% CI) = 0.80 (0.74–0.86); C-index (95% CI) excluding ctDNA = 0.67 (0.56–0.71).

Abbreviations: RFS, relapse-free survival; DMFS, distant metastasis-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA.

At the time of disease recurrence, patients with locoregional relapse had salvage surgery and all patients with distant metastatic relapse or unresectable disease received systemic therapy with a targeted agent or immune checkpoint inhibitor. Given the durable responses observed with these agents [19–24], there was no significant association between detectable ctDNA (at baseline or postoperatively) and OS at the median follow up of 20 months (supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Validation cohort

An independent prospectively collected cohort of 29 patients was used to validate ctDNA detection as a predictor of relapse (Figure 1, supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online). A total of 21/29 patients had a mutation identified. ctDNA was detected at baseline in 8/21(38%) patients and postoperatively in 6/16 (38%) patients with available plasma samples. Results were consistent with the MRV cohort with ctDNA detection at the postoperative timepoint predictive of RFS (HR 4.6; 95% CI 0.9–24; P = 0.045) and DMFS (HR 6.7; 95% CI 0.8–60; P = 0.049) (Figure 2E and F). Detectable baseline ctDNA in the validation cohort also predicted for RFS (HR 4.3; 95% CI 1.1–17; P = 0.03) and DMFS (HR 4.8; 95% CI 0.9–25; P = 0.04) (supplementary Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online).

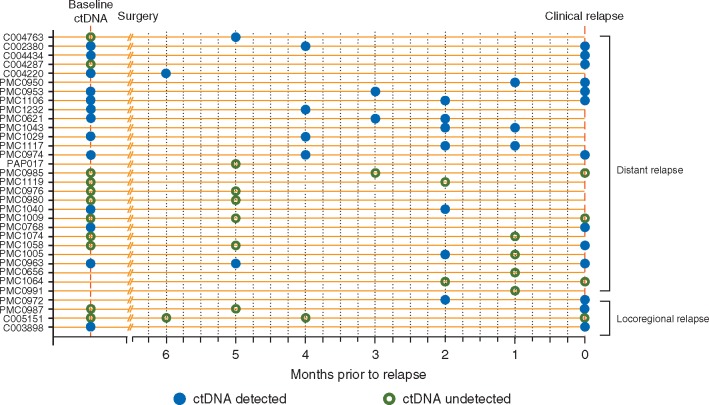

Disease surveillance using serial ctDNA analysis

Next, we examined the performance of serial ctDNA analysis during the surveillance period to actively detect disease relapse in patients from both the MRV and validation cohorts. Serial ctDNA results up to first clinical relapse are presented in Figure 3 for 33 patients (MRV cohort, n = 26 and validation cohort, n = 7) who had at least one plasma sample collected within 6 months of relapse. Here, ctDNA was detected in 16/33 (48%) patients prior to clinical relapse, with a median lead time of 2 months. The majority of these cases [15/16 (94%)] relapsed with distant metastatic disease. In a further six patients, ctDNA was detected at the time of clinical relapse, highlighting the ability of ctDNA to detect relapse in a total of 22/33 (67%) cases through serial analysis. In contrast, 38 patients had serial plasma samples collected within 6 months of last follow up and did not relapse during this period. Of these, 3/38 had detectable ctDNA. One of these cases was the patient diagnosed with the second malignancy (non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) and the other two cases had detectable ctDNA on serial sampling with no relapse as yet identified at follow up of 18 and 19 months, respectively (supplementary Table S8, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 3.

Serial ctDNA analysis and detection of relapse. Postoperative and serial plasma samples collected within 6 months of relapse were included in this analysis (n = 33). Clinical relapses were confirmed radiologically, or if equivocal by imaging, were confirmed by biopsy. ctDNA was detected prior to clinical relapse in 16 cases with a further 6 cases detected at the time of clinical relapse.

ctDNA dynamics in patients on adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor trials

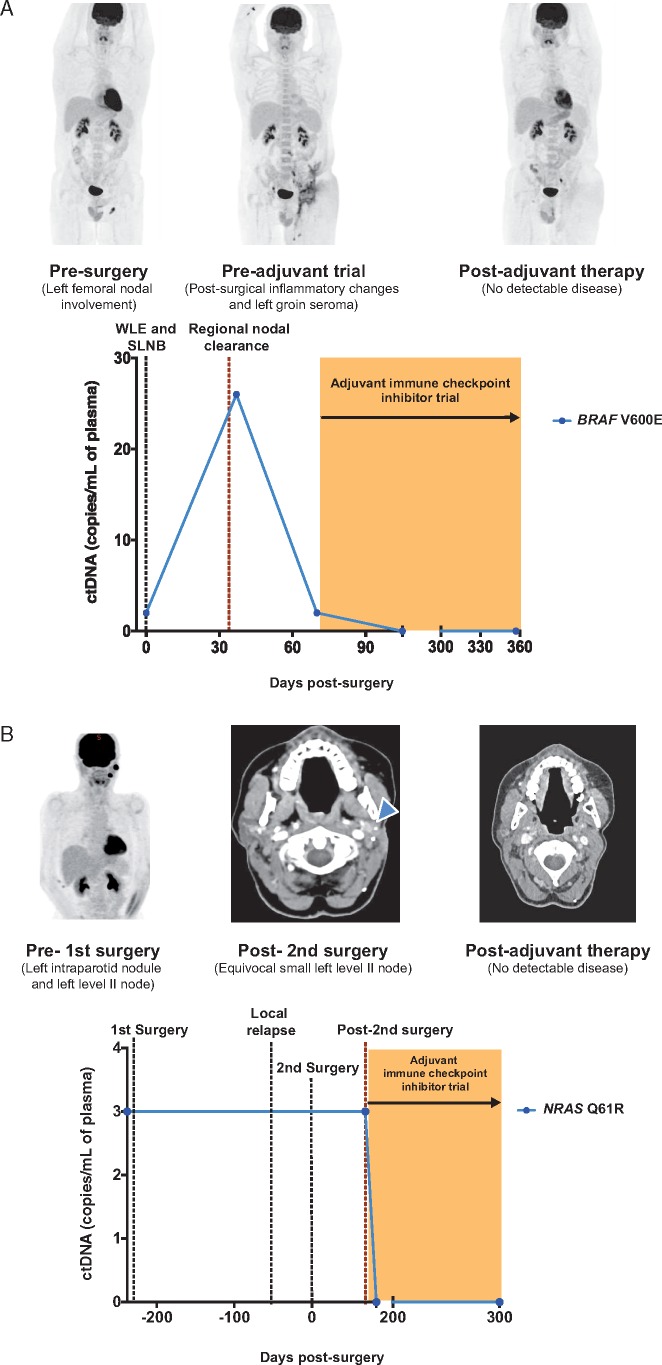

We next evaluated the role of serial ctDNA analysis in the MRV cohort of 18 patients who participated in adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor trials to determine if ctDNA dynamics could provide an early indication of treatment benefit. Fourteen out of the 18 patients did not have detectable ctDNA at either the baseline or postoperative timepoint. None of the 14 patients have relapsed to date.

In contrast, ctDNA was detectable in 4/18 individuals who participated in the adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor trials. In three patients, ctDNA was detected at baseline and remained detectable at the postoperative timepoint in two of these cases. In the fourth case, no baseline sample was available, however, ctDNA was detectable at the postoperative timepoint. Serial plasma samples were available in two cases and showed clearance of ctDNA levels after starting adjuvant immunotherapy (Figure 4A and B). At a median follow up of 7 months on treatment, none of these patients with detectable ctDNA at baseline or postoperatively have relapsed to date. This is in contrast to the relapse rate of 100% seen in the cohort of patients with detectable ctDNA at the postoperative timepoint who did not receive adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

Figure 4.

Serial ctDNA analysis in stage III patients treated on an adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor trial. (A) Patient PMC1327 with stage IIIC BRAF mutant melanoma had detectable ctDNA postoperatively signifying residual disease. Follow-up FDG-PET/CT scan post regional nodal clearance and prior to starting adjuvant therapy revealed post-surgical inflammatory changes and seroma with no evidence of recurrent or distant metastatic disease. ctDNA levels subsequently became undetectable post starting therapy on an adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor trial and have remained undetectable with no evidence of radiological detectable disease. (B) Patient PMC1242 had detectable ctDNA postoperatively following resection of a local recurrence of NRAS mutant stage IIIB melanoma. A follow-up CT scan prior to starting adjuvant therapy indicated an equivocal small left neck node (blue arrow head). After starting therapy on an adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor trial, ctDNA levels became undetectable and disease remained undetectable via radiological imaging. WLE, wide local excision; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Conclusion

Approximately 40%–90% of patients with resected stage III disease treated with curative intent will relapse within 5 years [25]. Recently, adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors and BRAF and MEK-targeted therapies have set a new standard in the treatment of stage III melanoma with improved RFS and OS [6–10]. Improved risk stratification of patients with resected stage III melanoma is needed to mitigate against unnecessary treatment in patients who are cured by surgery alone while identifying those at highest risk of relapse who are likely to benefit from adjuvant therapies. Our study has demonstrated that ctDNA analysis is predictive of relapse. Future studies will be needed to confirm if ctDNA analysis can be used for real-time surveillance of disease recurrence and provide an early readout of clearance of residual disease following adjuvant treatment.

We have recently demonstrated that ctDNA detection at a single postoperative timepoint within 12 weeks of surgery was predictive for relapse-free interval, distant metastasis-free interval and OS in a retrospective cohort of stage II and III melanoma patients in the AVAST-M adjuvant trial [26] We have now shown in two prospective cohorts that postoperative ctDNA detection is highly predictive of relapse in this patient group. Furthermore, we demonstrate for the first time that detectable pre-operative ctDNA is also predictive of outcome. Our study showed that baseline ctDNA levels increased with more advanced disease stage, which was associated with a higher likelihood of disease recurrence. Baseline ctDNA taken together with disease stage and pathological high-risk features of the primary tumor can refine prognostic estimates, provide an alternative source for mutational profiling and may guide early systemic treatment particularly in the neoadjuvant setting [27, 28]. Alternatively, the presence of ctDNA postoperatively signified residual micrometastatic disease following resection and was highly predictive of disease relapse. Importantly, our results from patients managed in Australia were prospectively validated in a smaller independent cohort in the UK. Despite the limited size of the validation cohort, the concordant results highlight the robustness of ctDNA to predict relapse in this setting.

In our analysis, the specificity of ctDNA to detect relapse was high, but the sensitivity could be further enhanced through improved technical approaches. We utilized a small volume of plasma and relied on detection of a single mutation in each case by ddPCR. ddPCR has several advantages for incorporation into routine molecular diagnostic workflows, including short turnaround time for analysis and reporting, and the high reproducibility across independent laboratories, as demonstrated in our analyses. However, ctDNA analysis methods are continuing to evolve, and ongoing technical advances are likely to improve the performance of future ctDNA-based assays for MRD detection.

In this series, the imaging surveillance regimen used FDG-PET/CT more frequently than is generally performed, potentially reducing the lead time for detection of clinical relapse [29, 30] In our study, despite some limitations in the number of serial samples collected across the cohort due to patient compliance, detection of clinical relapse via ctDNA analysis had excellent specificity, with ctDNA detection preceding clinical relapse in 48% of cases. Here, surveillance using ctDNA analysis could play an important role in guiding the timing of imaging as well as assisting in the interpretation of equivocal cases of radiological detected relapse [30, 31] Additionally, the ease of local blood collection, which can be sent to a central testing laboratory for processing and analysis, can facilitate more frequent disease assessment, particularly in patients who lack easy access to radiological imaging facilities.

Whilst the number of patients in our adjuvant therapy cohort was limited, we have demonstrated that ctDNA may be a useful biomarker to monitor the impact of adjuvant therapy following treatment. Importantly, none of the patients with undetectable ctDNA after starting adjuvant therapy have relapsed to date, however, this intriguing observation needs to be demonstrated in larger patient cohorts. Future efforts to enroll patients onto adjuvant clinical trials based on the detection of ctDNA are warranted and will be essential to establish the clinical utility of ctDNA analysis in this setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Sonia Mailer, Anne Fennesy, Nobel Zhang, Jane Brack, Karen Scott, Melanoma Research Victoria and the Melanoma Clinical Units at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, The Alfred Hospital, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and Manchester Cancer Research Centre (MCRC) Biobank for support in the enrolment of patients and sample and data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (grant number APP1107126), Cancer Research UK (grant numbers C5759/A20971) and the Wellcome Trust (grant number 100282/Z/12/Z). SJD is supported through a CSL Centenary Fellowship.

Disclosures

SS reports receiving advisory board fees from Merck, BMS, Roche and research support from BMS, Amgen, Astra Zeneca and Merck. MS reports receiving travel support: BMS, Merck, Roche. Consultancy: BMS, Merck, MSD. Honoraria: BMS, Merck, MSD. Research support: BMS. Advisory Board: MSD. DEG reports receiving honorarium and advisory board fees from Amgen. RM reports receiving research funding from Basilea pharmaceutical and rewards from Institute of Cancer Research. PL has consultant/advisory role: BMS, Novartis, MSD, NeraCare, Amgen, Pierre Fabre, Incyte. Honoraria: BMS, Novartis, Incyte, MSD, Amgen, NeraCare, PierreFabre. Research funding: BMS. Travel support: BMS, MSD, PierreFabre, Incyte. SQW reports receiving travel support from BioRad. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Faries MB, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ. et al. Completion dissection or observation for sentinel-node metastasis in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(23): 2211–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68(1): 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR. et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67(6): 472–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coit DG, Thompson JA, Algazi A. et al. Melanoma, version 2.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14(4): 450–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marsden JR, Newton-Bishop JA, Burrows L. et al. Revised UK guidelines for the management of cutaneous melanoma 2010. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010; 63(9): 1401–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ. et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(5): 522–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M. et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(19): 1824–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M. et al. Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(19): 1813–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M. et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(19): 1789–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eggermont AMM, Chiarion-Silenia V, Grob J-J. et al. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(19): 1845–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wong SQ, Raleigh JM, Callahan J. et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis and functional imaging provide complementary approaches for comprehensive disease monitoring in metastatic melanoma. JCO Precis Oncol 2017; (1): 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tie J, Cohen JD, Wang Y. et al. Serial circulating tumour DNA analysis during multimodality treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: a prospective biomarker study. Gut 2018; 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olsson E, Winter C, George A. et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor DNA in patients with primary breast cancer for detection of occult metastatic disease. EMBO Mol Med 2015; 7(8): 1034–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tie J, Wang Y, Tomasetti C. et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis detects minimal residual disease and predicts recurrence in patients with stage II colon cancer. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8(346): 346–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garcia-Murillas I, Schiavon G, Weigelt B. et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7(302): 302–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abbosh C, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA. et al. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature 2017; 545(7655): 446–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Richter A, Grieu F, Carrello A. et al. A multisite blinded study for the detection of BRAF mutations in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded malignant melanoma. Sci Rep 2013; 3: 1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS.. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics 2000; 56(2): 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C. et al. Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(17): 1889–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Robert C, Long GV, Brady B. et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(4): 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV. et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(26): 2521–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J. et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(1): 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C. et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(26): 2507–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R. et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(14): 1345–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Romano E, Scordo M, Dusza SW. et al. Site and timing of first relapse in stage III melanoma patients: implications for follow-up guidelines. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(18): 3042–3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee RJ, Gremel G, Marshall A. et al. Circulating tumor DNA predicts survival in patients with resected high-risk stage II/III melanoma. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(2): 490–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Amaria RN, Reddy S, Tawbi HA. et al. Neodjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in high-risk resectable melanoma. Nat Med 2018; 24(11): 1649–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blank CU, Rozeman EA, Fanchi LF. et al. Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma. Nature Med 2018; 24(11): 1655–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xing Y, Bronstein Y, Ross MI. et al. Contemporary diagnostic imaging modalities for the staging and surveillance of melanoma patients: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103(2): 129–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lewin J, Sayers L, Kee D. et al. Surveillance imaging with FDG-PET/CT in the post-operative follow-up of stage 3 melanoma. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(7): 1569–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wong SQ, Tothill RW, Dawson SJ. et al. Wet or dry? Do liquid biopsy techniques compete with or complement PET for disease monitoring in oncology? J Nucl Med 2017; 58(6): 869–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.