Abstract

This study uses National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data to assess the percentage of psychiatrists who have accepted Medicaid-insured patients before and after Medicaid expansion.

Medicaid is the principal payer of behavioral health services in the United States and has been expected to play an increasing role in financing behavioral health services after states’ implementation of Medicaid expansions.1,2 Little is known about recent trends in psychiatrists’ acceptance of Medicaid, including before and after 2014, when most Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act went into effect. Without adequate participation in Medicaid among psychiatrists, Medicaid enrollees with behavioral health needs may be unable to find a local psychiatrist who accepts new patients with Medicaid or have to wait a long time for an intake appointment.3,4

Methods

We used the 2010-2015 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), a nationally representative survey of physicians who were not federally employed, were based in offices, and were primarily engaged in direct patient care.5 Medicaid acceptance was created based on 2 questions. The NAMCS first asked, “Are you currently accepting new patients into your practice?” and then asked, “From those new patients, which of the following types of payment do you accept?” (with answer choices of payment via private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program, worker’s compensation, self-payment, and/or no charge/charity care). We limited the study sample to physicians who reported accepting new patients.

We compared the trend differences in physician acceptance of new patients with Medicaid across 2-year spans (2010-2011, 2012-2013, and 2014-2015) by physician specialty, grouping physician specialties into 3 broad categories: (1) psychiatry; (2) primary care, including general and family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics; and (3) other nonpsychiatry specialties. We also examined differences in Medicaid acceptance before and after expansion between expansion and nonexpansion states by physician specialty, which is analogous to a stratified difference-in-differences analysis. Geographic identifiers that allowed for the classification of Medicaid expansion were only available after 2012 and for 18 large states (Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin), which collectively represented 60% of the physician sample (or 73%, weighted) between 2012 and 2015. For most expansion states and all nonexpansion states, the preexpansion period was 2012 through 2013 and the postexpansion period was 2014 through 2015; exceptions were Indiana and Pennsylvania, for which the preexpansion data were for 2012 through 2014 and the postexpansion period was 2015. Analyses were weighted using NAMCS national weights. The trend analysis from 2010 through 2015 was adjusted for individual-level covariates, including ownership status, practice size, practice region, and metropolitan statistical area status. The difference-in-differences analysis from 2012 to 2015 was also adjusted for state-level managed care penetration rate, unemployment rate, poverty rate, and median household income, as well as 2-way fixed effects for state and year. Standard errors were clustered at the state level.

This study used deidentified data from publicly available sources, which removed the need to implement an informed consent procedure. It was deemed an exempt human research study by the University of Kentucky institutional review board.

Data analysis occurred from July 2018 to September 2018 using Stata/SE version 15 (StataCorp). Statistical significance was assessed with significance set at P < .05, using 2-sided tests.

Results

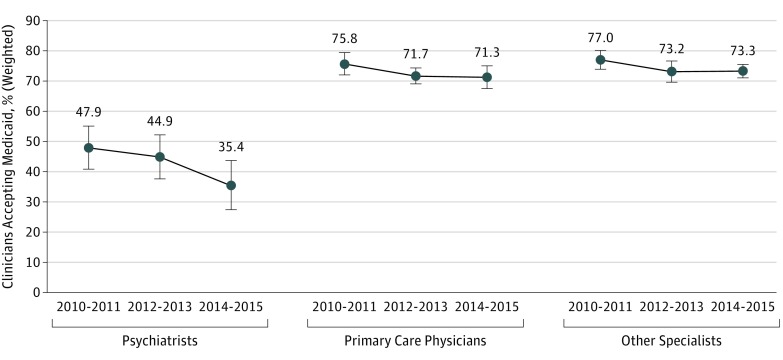

A total of 11 521 NAMCS respondents (95% of the total sample) reported seeing new patients, including 584 psychiatrists, 4400 primary care physicians, and 6537 other specialists. During each period we examined, psychiatrists were less likely than primary care physicians and other specialists to accept new patients with Medicaid (psychiatrists: 2010-2011, 47.93% [95% CI, 40.81%-55.05%]; 2012-2013, 44.94% [95% CI, 37.63$-52.24%]; 2014-2015, 35.43% [95% CI, 27.26%-43.59%]; primary care physicians: 2010-2011, 75.78% [95% CI, 72.11%-79.45%]; 2012-2013, 71.73% [95% CI, 69.11%-74.35%]; 2014-2015, 71.29% [95% CI, 67.53%-75.05%]; other specialists: 2010-2011, 76.99% [95% CI, 73.94%-80.04%]; 2012-2013, 73.22% [95% CI, 69.75%-76.69%]; 2014-2015, 73.33% [95% CI, 71.11%-75.55%]; all comparisons, P < .001; Figure 1). Furthermore, there was a significant decline in the likelihood of psychiatrists accepting new patients with Medicaid. The likelihood of psychiatrists accepting Medicaid declined from 47.9% from 2010 through 2011 to 44.9% from 2012 through 2013 (Figure 1; P = .04) and to 35.4% in 2014 through 2015 (P = .01). In contrast with these declines, no significant change in Medicaid acceptance was found among primary care physicians or other specialists.

Figure 1. Adjusted Trend Difference in Medicaid Acceptance Across Physician Specialties.

Point estimates are shown as dots; 95% CIs, as lines with bars. Analyses were weighted by the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey’s national weights and adjusted for practice ownership status (full owner, part owner, employee, or contractor), practice size (solo practice or group practice), practice region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West), and metropolitan statistical area status (metropolitan, micropolitan, or rural).

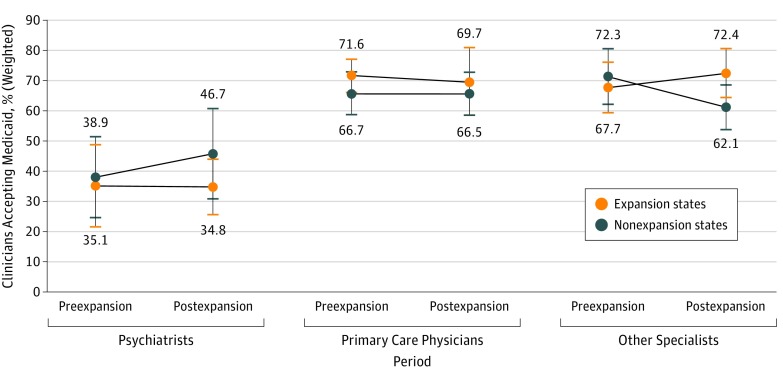

The adjusted difference-in-differences estimates suggest Medicaid expansion was not associated with a discernable change in the likelihood of accepting new patients with Medicaid among psychiatrists (Figure 2; −7.89% [95% CI, −40.03 to 24.24]; P = .63). Furthermore, Medicaid expansion was associated with an increase in Medicaid acceptance among other specialists (14.0% [95% CI, 7.12-20.89]; P < .001) but not with a change in Medicaid acceptance among primary care physicians (−1.82% [95% CI, −13.38 to 9.74]; P = .76).

Figure 2. Adjusted Differences in Medicaid Acceptance Before and After Medicaid Expansion Between Expansion and Nonexpansion States and Across Physician Specialties.

Point estimates are shown as colored dots; 95% CIs, as lines with bars. Estimates for the expansion states are in yellow; nonexpansion states, dark blue. Analyses were weighted by the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey’s national weights and adjusted for individual-level covariates, including practice ownership status (full owner, part owner, employee, or contractor), practice size (solo practice or group practice), and metropolitan statistical area status (metropolitan, micropolitan, or rural); state-level covariates, including rates of comprehensive risk-based Medicaid managed care enrollment, unemployment, and poverty and median household income; and 2-way fixed effects for state and year. Standard errors were clustered at the state level to correct for within-state serial correlation in error terms.

Discussion

Owing to declines in psychiatrist participation in Medicaid, patient gains in insurance coverage under Medicaid expansion may not translate into meaningful improvements in access to office-based treatment by psychiatrists. This study was limited by the relatively small physician sample size in the NAMCS and only 2 years’ postexpansion data in most expansion states. Furthermore, low Medicaid participation among primary care physicians has been attributed to low Medicaid physician fees, reimbursement delays, and administrative burden.6 However, we lacked data to explore the relative importance of these potential factors in psychiatrists’ decision to accept Medicaid patients.

This topic merits future study. The patterns we observed in Medicaid acceptance among psychiatrists over time suggest that factors other than Medicaid expansion must account for these findings. Future research is also needed to identify interventions, such as team-based care coordination approaches, to increase Medicaid capacity to care for patients with behavioral health care needs.

References

- 1.Garfield RL, Lave JR, Donohue JM. Health reform and the scope of benefits for mental health and substance use disorder services. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(11):1081-1086. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garfield RL, Zuvekas SH, Lave JR, Donohue JM. The impact of national health care reform on adults with severe mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):486-494. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176-181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummings JR. Rates of psychiatrists’ participation in health insurance networks. JAMA. 2015;313(2):190-191. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Health Statistics; Center for Disease Control and Prevention Ambulatory health care data. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/index.htm. Published 2017. Accessed November 29, 2017.

- 6.Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1673-1679. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]