Key Points

Question

Has the expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act been associated with any differences in cardiovascular mortality rates?

Findings

In this difference-in-differences analysis, states that expanded eligibility for Medicaid had a significantly smaller increase in rates of cardiovascular mortality for middle-aged adults after expansion than states that did not expand Medicaid.

Meaning

Medicaid expansion was associated with lower cardiovascular mortality and may be an important consideration for states debating expansion of Medicaid eligibility.

This difference-in-differences analysis investigates the association of Medicaid expansion with cardiovascular mortality rates for middle-aged adults using data from 48 states and Washington, DC.

Abstract

Importance

Medicaid expansion under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act led to one of the largest gains in health insurance coverage for nonelderly adults in the United States. However, its association with cardiovascular mortality is unclear.

Objective

To investigate the association of Medicaid expansion with cardiovascular mortality rates in middle-aged adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study used a longitudinal, observational design, using a difference-in-differences approach with county-level data from counties in 48 states (excluding Massachusetts and Wisconsin) and Washington, DC, from 2010 to 2016. Adults aged 45 to 64 years were included. Data were analyzed from November 2018 to January 2019.

Exposures

Residence in a Medicaid expansion state.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Difference-in-differences of annual, age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality rates from before Medicaid expansion to after expansion.

Results

As of 2016, 29 states and Washington, DC, had expanded Medicaid eligibility, while 19 states had not. Compared with counties in Medicaid nonexpansion states, counties in expansion states had a greater decrease in the percentage of uninsured residents at all income levels (mean [SD], 7.3% [3.2%] vs 5.6% [2.7%]; P < .001) and in low income strata (19.8% [5.5%] vs 13.5% [3.9%]; P < .001) between 2010 and 2016. Counties in expansion states had a smaller change in cardiovascular mortality rates after expansion (146.5 [95% CI, 132.4-160.7] to 146.4 [95% CI, 131.9-161.0] deaths per 100 000 residents per year) than counties in nonexpansion states did (176.3 [95% CI, 154.2-198.5] to 180.9 [95% CI, 158.0-203.8] deaths per 100 000 residents per year). After accounting for demographic, clinical, and economic differences, counties in expansion states had 4.3 (95% CI, 1.8-6.9) fewer deaths per 100 000 residents per year from cardiovascular causes after Medicaid expansion than if they had followed the same trends as counties in nonexpansion states.

Conclusions and Relevance

Counties in states that expanded Medicaid had a significantly smaller increase in cardiovascular mortality rates among middle-aged adults after expansion compared with counties in states that did not expand Medicaid. These findings suggest that recent Medicaid expansion was associated with lower cardiovascular mortality in middle-aged adults and may be of consideration as further expansion of Medicaid is debated.

Introduction

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) led to the largest expansion of Medicaid coverage since the inception of the program.1 Under the ACA, beginning in 2014, all nonelderly US citizens and permanent residents (with more than 5 years of residency) with an income up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) became eligible for Medicaid. However, a number of states have not expanded eligibility for Medicaid, and there is continued debate regarding further changes in eligibility criteria.2,3

Observational studies have demonstrated that prior efforts to expand health insurance coverage in individual states were associated with improved health outcomes, including lower mortality rates.4,5 However, a single-state randomized clinical trial of Medicaid expansion did not show conclusive evidence of improvements in several intermediate health measures.6 In a recent analysis of patients with end-stage renal disease, Medicaid expansion was associated with lower all-cause mortality.7

Cardiovascular disease and its risk factors disproportionately affect individuals of lower socioeconomic status and those who are uninsured.8,9 Since Medicaid expansion has been associated with improvements in the management of diabetes,10 increased use of cardioprotective medications,11 and access to preventive care,12 expansion in health insurance coverage may have a potential association with cardiovascular disease and mortality. Medicaid expansion has also been associated with fewer cardiovascular hospitalizations without insurance.13 However, studies of in-hospital cardiovascular outcomes have not shown a significant association with Medicaid expansion.14,15 It is unclear whether Medicaid expansion has had an association with overall cardiovascular mortality rates in the population. The aim of this analysis was therefore to assess whether there have been differential changes in cardiovascular mortality rates in nonelderly adults living in states that expanded Medicaid eligibility compared with those in states that did not expand Medicaid eligibility between 2010 and 2016.

Methods

Data Sources

Because Medicaid coverage expansion has a greater outcome on individuals younger than 65 years and cardiovascular diseases are more prevalent in older adults,16 we focused this study on cardiovascular mortality rates among adults 45 to 64 years of age. We obtained annual, county-level cardiovascular mortality rates, age-adjusted to the 2000 US population, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research mortality database from 2010 to 2016 for all 50 states and Washington, DC.17 Causes of deaths were limited to diseases of the circulatory system (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision codes I00 to I99). Counties with fewer than 10 deaths per year are censored from the publicly visible version of the Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research database and were not included in this analysis. Because all the data analyzed are publicly available and aggregated at the county or state level, the project is considered exempt from institutional review board review based on guidelines from the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board. Informed consent was not obtained because of the aggregate and deidentified nature of the data.

Data on county-level percentages of residents who were female, black (non-Hispanic black, either alone or in combination with other races), Hispanic, living in poverty, and unemployed were obtained from the US Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics.18,19,20 Additionally, the median inflation-adjusted household income (in 2016 dollars) was obtained. Percentage of residents with health insurance was also obtained from the US Census Bureau and was aggregated for residents aged 40 to 64 years.21 The number of primary care clinicians and cardiologists per 100 000 residents was obtained from the Health Resources and Services Administration Area Health Resource File.22 Because data for cardiologists were only available for the years 2010, 2015, and 2016, the population density of cardiologists in 2010 was assigned to all years from 2010 to 2014. Diabetes, obesity, and smoking prevalence at baseline were based on the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.23

Outcome Measure

The primary outcome measure was county-level, age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality rates per 100 000 adults aged 45 to 64 years. As sensitivity measures, we also examined cardiovascular mortality rates of residents aged 25 to 64 years and 65 to 74 years.

Study Design and Intervention

We used a quasiexperimental study design based on a difference-in-differences (DID) estimator. This approach aims to isolate the association of an intervention in observational data by comparing differences in an outcome over time between groups that received an intervention vs groups that did not.24

The main intervention of interest was the expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the ACA. The following states expanded Medicaid eligibility effective January 1, 2014: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, and West Virginia.25 Another 6 states expanded eligibility at a later date: Michigan (April 1, 2014), New Hampshire (August 15, 2014), Pennsylvania (January 1, 2015), Indiana (February 1, 2015), Alaska (September 1, 2015), and Montana (January 1, 2016). The remainder of the states were designated as nonexpansion states. Owing to prior Medicaid eligibility expansion in Massachusetts and coverage of adults up to 100% of the FPL in Wisconsin, these 2 states were excluded from the main analysis. Another 6 states (California, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Washington) had limited expansions of Medicaid eligibility after the passage of the ACA but prior to 2014. These states were included in the main analysis but were excluded in a sensitivity analysis along with the 6 late-adopter states.

The years 2010 through 2013 were designated as the preexpansion period and 2014 through 2016 were the postexpansion period for most of the states. For the states that expanded Medicaid eligibility later than 2014, the postexpansion period began in the year expansion was implemented (ie, 2015 for New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Indiana, and 2016 for Alaska and Montana). States that expanded Medicaid after the beginning of the calendar year had the entire year designated as a postexpansion year.

Analysis

We first compared county-level variables between counties in states that expanded Medicaid eligibility and those that did not, using the t test and Pearson χ2 test. We then estimated cardiovascular mortality rates for each of the study years separately for expansion and nonexpansion counties using a multilevel linear regression model with county fixed effects and random intercepts for each state. Huber-White heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors were calculated, accounting for clustering at the state level and autocorrelation of repeated measures across years. We then estimated adjusted mortality rates by including the following covariates: the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification designation (metropolitan vs nonmetropolitan county), the percentages of residents aged 45 to 64 years who were female, black, and Hispanic; the percentages of residents living in poverty and unemployed; the percentages of adult residents with diabetes and obesity in 2010; the percentage of adult residents who smoke in 2010; the percentage of residents aged 40 to 64 years with income less than 138% of the FPL who had health insurance in 2010; the median household income; the number of primary care clinicians per 100 000 residents; and the number of cardiologists per 100 000 residents.

To test the association of Medicaid expansion on mortality, we constructed another linear regression model with the same structure and added an indicator for Medicaid expansion status, an indicator for the preexpansion or postexpansion period, and an interaction term between expansion status and period as the independent variables in the model (eMethods 1 in the Supplement). The interaction term is the DID estimator. An indicator variable for the year was also included to account for the variation in years in which different states entered the postexpansion period. We repeated this model with the addition of previously mentioned county-level covariates. We then analyzed some subgroups of interest: metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties, counties in which more than 10% of residents aged 45 to 64 years were black in 2010, counties in the top 50th percentile for the percentage of residents living in poverty in 2010, counties in the top 50th percentile of cardiovascular mortality in 2010, and counties in the top and bottom 50th percentiles for percentage of residents with low income aged 40 to 64 years without health insurance in 2010. We also repeated the DID analysis separately for the top and bottom 50th percentiles of the absolute change in the number of low-income residents with health insurance between 2010 and 2016.

We also conducted some sensitivity analyses. These included using cardiovascular mortality of individuals aged 65 to 74 years as the outcome, because this age group was not primarily affected by Medicaid expansion. Other analyses included excluding all early-adopter and late-adopter states and using data aggregated at the state level (to include deaths that were censored from the county-level analysis). We also tested the assumption that time trends were similar between the 2 groups prior to Medicaid expansion. Details are presented in eMethods 3, eTable 4, and eTable 5 in the Supplement.

Because the primary unit of measurement was at the county level and the variance of each aggregate point estimate is a function of its underlying population size,26 we weighted all of these analyses with the county population of residents aged 45 to 64 years. Data are presented as means with SDs or 95% CIs or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), as indicated. All P values were 2-sided, and P values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Baseline County Characteristics

Counties in 29 expansion states plus Washington, DC, were included in the intervention (expansion) group, while counties in 19 nonexpansion states were in the control (nonexpansion) group. After excluding censored counties with fewer than 10 deaths per year, the number of counties included ranged between 902 to 931 in expansion states and 985 to 1029 for nonexpansion states over the study period (Table 1). Censored counties accounted for less than 5% of the total 79.7 million middle-aged adults living in the included states. Expansion counties were less likely to be in the Southern US Census region compared with nonexpansion counties (200 [21.9%] vs 836 [84.1%]; P < .001). In 2010, counties in expansion states had a higher median population (16 595 [IQR, 9030-42 640] vs 11 114.5 [IQR, 6514-25 225]; P < .001). The percentage of black residents was lower (mean [SD], 9.6% [11.1%] vs 16.5% [14.0%]; P < .001) in counties in expansion states, with no significant difference in the percentage of Hispanic residents. In 2010, expansion counties also had a lower prevalence of diabetes (mean [SD], 8.5 % [1.5%] vs 9.7% [1.6%]; P < .001), obesity (mean [SD], 26.2% [4.6%] vs 29.1% [4.2%]; P < .001), and smoking (mean [SD], 17.1% [4.7%] vs 18.9% [5.2%]; P < .001); a lower percentage of poor residents (mean [SD], 14.4% [5.0%] vs 16.6% [5.4%]; P < .001); and a higher median household income (median [IQR], $57 653.60 [$49 490.30-$69 431.40] vs $50 369.40 [$44 279.80-$57 251.00]; P < .001) than nonexpansion counties.

Table 1. County-Level Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid Expansion States | Medicaid Nonexpansion States | ||

| States, No. | 30a | 19 | NA |

| Counties included, No. | |||

| 2010 | 912 | 994 | NA |

| 2011 | 902 | 989 | |

| 2012 | 905 | 992 | |

| 2013 | 923 | 985 | |

| 2014 | 923 | 1013 | |

| 2015 | 918 | 1012 | |

| 2016 | 931 | 1029 | |

| US census region, % | |||

| South | 21.9 | 84.1 | <.001 |

| Northeast | 18.9 | 1.5 | <.001 |

| Midwest | 39.3 | 11.5 | <.001 |

| West | 20.0 | 2.9 | <.001 |

| Nonmetropolitan counties, % | 48.0 | 50.9 | .21 |

| Residents aged 45-64 y per county in 2010, median (IQR)b | 16 595 (9030-42 640) | 11 114.5 (6514-25 225) | <.001 |

| County residents aged 45-64 y without insurance, % | |||

| In 2010 | 14.6 (5.1) | 19.5 (6.0) | <.001 |

| Change in percentage, 2010-2016 | 7.3 (3.2) | 5.6 (2.7) | <.001 |

| County residents aged 45-64 y without insurance with income <138% of the federal poverty line, % | |||

| In 2010 | 35.6 (8.0) | 44.9 (7.9) | <.001 |

| Percentage change, 2010-2016 | 19.8 (5.5) | 13.5 (3.9) | <.001 |

| Demographic attributes in county residents aged 45-64 y in 2010, % | |||

| Female | 51.2 (1.2) | 51.5 (1.4) | <.001 |

| Black | 9.6 (11.1) | 16.5 (14.0) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 11.4 (12.0) | 11.0 (16.2) | .57 |

| Attributes of county residents in 2010, % | |||

| Unemployed adults | 10.1 (2.5) | 9.5 (2.3) | <.001 |

| In poverty | 14.4 (5.0) | 16.6 (5.4) | <.001 |

| With diabetes | 8.5 (1.5) | 9.7 (1.6) | <.001 |

| With obesity | 26.2 (4.6) | 29.1 (4.2) | <.001 |

| Smoking | 17.1 (4.7) | 18.9 (5.2) | <.001 |

| County household income in 2010, median (IQR), $c | 57 653.6 (49 490.3- 69 431.4) |

50 369.4 (44 279.8- 57 251.0) |

<.001 |

| Clinicians per 100 000 residents in 2010 | |||

| Primary care clinicians | 78.3 (27.7) | 65.7 (25.3) | <.001 |

| Cardiologists | 7.7 (6.4) | 6.6 (5.3) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NA, not available.

Included 29 states and Washington, DC.

Summary measure not weighted by county population.

In 2016 dollars.

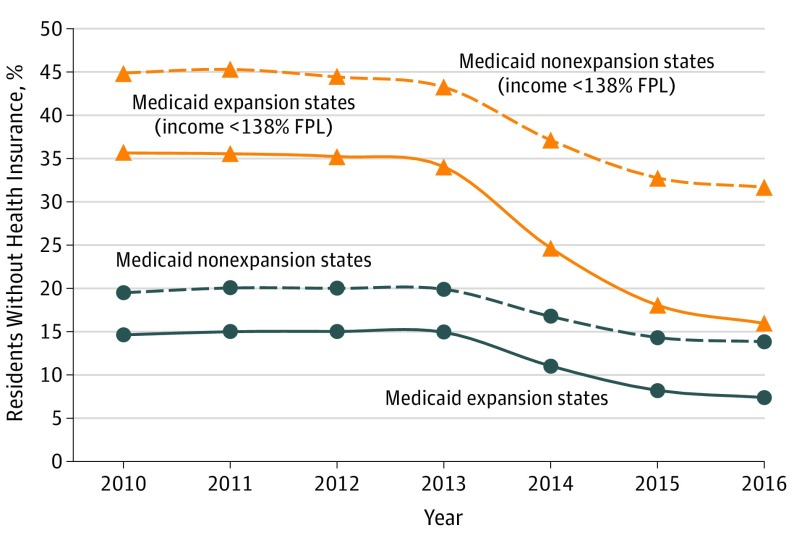

Health Insurance Coverage

In 2010, the proportions of residents aged 40 to 64 years without health insurance coverage were significantly lower in expansion counties than in nonexpansion counties for all income levels (mean [SD], 14.6% [5.1%] vs 19.5% [6.0%]; P < .001) and among those with income less than 138% of the FPL who were without insurance (mean [SD], 35.6% [8.0%] vs 44.9% [7.9%]; P < .001) (Table 1). Health insurance coverage for both groups of counties was relatively stable between 2010 and 2013 (Figure 1 and eTable 1 in the Supplement). Between 2010 and 2016, there was a larger decrease in the percentages of residents aged 40 to 64 years without insurance in counties in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states at all income levels (mean [SD], 7.3% [3.2%] vs 5.6% [2.7%]; P < .001) and in residents with low income who were without insurance (mean [SD], 19.8% [5.5%] vs 13.5% [3.9%]; P < .001).

Figure 1. Percentage of Residents Aged 40 to 64 Years Without Health Insurance Coverage.

FPL indicates the federal poverty line.

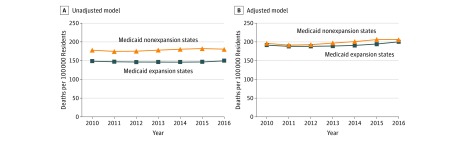

Cardiovascular Mortality Rates

Age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality rates for residents aged 45 to 64 years were significantly lower in counties in expansion states compared with counties in nonexpansion states between 2010 (147.9 [95% CI, 134.0-161.9] vs 177.6 [95% CI, 155.3-199.9] deaths per 100 000 residents per year) and 2013 (145.6 [95% CI, 131.4-159.8] vs 177.8 [95% CI, 154.7-200.8] deaths per 100 000 residents per year), but overall trends were similar between the 2 groups prior to expansion (Figure 2; eTable 2 and eTable 4 in the Supplement). Accounting for differences in the previously mentioned covariates significantly reduced the differences between the 2 groups (2010: expansion counties, 190.7 [95% CI, 181.5-200.0] deaths per 100 000 residents per year for vs nonexpansion counties; 195.3 [95% CI, 184.9-205.8] deaths per 100 000 residents per year for nonexpansion counties). The differences between the 2 groups increased in 2014 and 2015 and narrowed again in 2016 (adjusted cardiovascular mortality: expansion counties, 2014, 190.1 [95% CI, 180.4-199.8] vs nonexpansion counties, 199.8 [95% CI, 188.4-211.1] deaths per 100 000 residents per year; 2015: 193.6 [95% CI, 183.8-203.5] vs 204.9 [95% CI, 192.8-216.9] deaths per 100 000 residents per year; 2016: 199.2 [95% CI, 188.6-209.8] vs 205.1 [95% CI, 193.5-216.7] deaths per 100 000 residents per year; eMethods 2 and eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Annual Cardiovascular Mortality Rates in Residents Aged 45 to 64 Years by State Medicaid Expansion Status.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates

In counties in expansion states, cardiovascular mortality was stable between the preexpansion and postexpansion periods (146.5 [95% CI, 132.4-160.7] to 146.4 [95% CI, 131.9-161.0] deaths per 100 000 residents per year) (Table 2). There was an increase in cardiovascular mortality rates in nonexpansion counties between the preexpansion and postexpansion periods (176.3 [95% CI, 154.2-198.5] to 180.9 [95% CI, 158.0-203.8] deaths per 100 000 residents per year). The unadjusted and adjusted DID estimates comparing expansion vs nonexpansion counties were −4.6 (95% CI, −7.5 to −1.8; P = .001) and −4.3 (95% CI, −6.9 to −1.8; P = .001), respectively. Therefore, after accounting for differences in demographic, clinical, economic, and health access variables, counties in expansion states had 4.3 (95% CI, 1.8-6.9) fewer deaths from cardiovascular causes per 100 000 residents per year after Medicaid expansion compared with the deaths that would have occurred if they had followed the same trajectory as seen in counties in nonexpansion states. Among the included counties in expansion states, which had a population of 47.4 million middle-aged adults in 2014; this translates to a total of 2039 (95% CI, 853-3271) fewer total deaths per year in residents aged 45 to 64 years from cardiovascular causes after Medicaid expansion.

Table 2. Differences-in-Differences Analysisa.

| Group | Cardiovascular Deaths per 100 000 Residents per Year, Unadjusted, Mean (SD) | Difference-in-Differences Estimate (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre–Medicaid Expansion Period | Post–Medicaid Expansion Period | Unadjusted | P Value | Adjusteda | P Value | |

| Overall | ||||||

| Medicaid expansion states | 146.5 (132.4-160.7) | 146.4 (131.9-161.0) | −4.6 (−7.5 to −1.8) | .001 | −4.3 (−6.9 to −1.8) | .001 |

| Medicaid nonexpansion states | 176.3 (154.2-198.5) | 180.9 (158.0-203.8) | ||||

| Metropolitan counties | ||||||

| Medicaid expansion states | 139.4 (126.3-152.4) | 139.6 (125.9-153.3) | −4.0 (−6.5 to −1.6) | .001 | −3.7 (−6.3 to −1.2) | .005 |

| Medicaid nonexpansion states | 163.9 (144.1-183.7) | 168.1 (147.8-188.4) | ||||

| Nonmetropolitan counties | ||||||

| Medicaid expansion states | 168.5 (1513-185.6) | 168.9 (152.0-185.7) | −6.4 (−12.5 to −0.2) | .04 | −6.2 (−12.5 to 0.1) | .05 |

| Medicaid nonexpansion states | 227.0 (200.9-253.0) | 233.7 (206.4-261.0) | ||||

| Counties with >10% black residents in 2010 | ||||||

| Medicaid expansion states | 176.9 (157.8-196.1) | 175.2 (154.8-195.6) | −4.5 (−8.0 to −1.0) | .01 | −4.3 (−7.7 to −0.9) | .01 |

| Medicaid nonexpansion states | 199.9 (178.2-221.5) | 202.7 (179.6-225.7) | ||||

| Top 50th percentile for residents living in poverty in 2010b | ||||||

| Medicaid expansion states | 178.8 (160.9-196.4) | 177.9 (159.1-196.6) | −6.6 (−10.7 to −2.5) | .002 | −5.3 (−9.0 to −1.6) | .01 |

| Medicaid nonexpansion states | 205.4 (183.1-227.7) | 211.1 (187.5-234.8) | ||||

| Top 50th percentile for cardiovascular mortality in 2010c | ||||||

| Medicaid expansion states | 185.7 (174.5-196.9) | 187.0 (174.8-199.2) | −5.7 (−9.4 to −2.1) | .002 | −5.2 (−9.1 to −1.4) | .01 |

| Medicaid nonexpansion states | 206.5 (191.1-221.8) | 213.6 (197.2-229.9) | ||||

| Top 50th percentile for percentage of population uninsured in 2010d | ||||||

| Medicaid expansion states | 135.2 (117.5-152.8) | 130.1 (112.5-147.8) | −4.4 (−8.2 to −0.5) | .03 | −3.4 (−6.6 to −0.2) | .04 |

| Medicaid nonexpansion states | 174.1 (151.4-196.9) | 173.5 (149.8-197.2) | ||||

| Bottom 50th percentile for percentage of population uninsured in 2010e | ||||||

| Medicaid expansion states | 155.0 (137.7-172.2) | 155.3 (137.5-173.1) | −8.7 (−12.6 to −4.7) | <.001 | −7.5 (−12.0 to −3.0) | .001 |

| Medicaid nonexpansion states | 205.9 (175.4-236.3) | 214.9 (184.2-245.6) | ||||

Adjusted for 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification designation (metropolitan vs nonmetropolitan county), percentage of residents living in poverty, percentage of adults unemployed, inflation-adjusted median household income, percentage of residents aged 40 to 64 years who were female, percentage of residents aged 40 to 64 years who were black, percentage of residents aged 40 to 64 years who were Hispanic, percentage of adult residents with diabetes in 2010, percentage of adult residents with obesity in 2010, percentage of adult residents who smoke in 2010, number of primary care clinicians per 100 000 residents, number of cardiologists per 100 000 residents, and percentage of residents aged 40 to 64 years with income less than 138% of the federal poverty limit with health insurance in 2010.

Greater than or equal to 15.2% of residents.

Greater than or equal to 145.1 deaths per 100 000 residents.

Greater than or equal to 39% of residents aged 40 to 64 years with income less than 138% of the federal poverty limit.

Less than 39% of residents aged 40 to 64 years with income less than 138% of the federal poverty limit.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

In the subgroup analyses, the adjusted DID estimate was attenuated but statistically significant in metropolitan counties (−3.7 [95% CI, −6.3 to −1.2]; P = .005; Table 2). The adjusted DID estimate was larger for nonmetropolitan counties but not significantly so (−6.2 [95% CI, −12.5 to 0.10]; P = .05). The DID estimate was also larger for counties in the top 50th percentile for residents living in poverty in 2010 (−5.3 [95% CI, −9.0 to −1.6]; P = .01). The adjusted DID estimate was more prominent for counties in the bottom 50th percentile for baseline percentage of uninsured residents (−7.5 [95% CI, −12.0 to −3.0]; P = .001) compared with counties in the top 50th percentile (−3.4 [95% CI, −6.6 to −0.2]; P = .04).

The adjusted DID estimate was significant when comparing the top 50th percentile of expansion counties for change in the number of residents with low income and health insurance with all nonexpansion counties (−4.8 [95% CI, −7.5 to −2.2]; P < .001) (Table 3). However, the DID estimate was not significant when comparing the bottom 50th percentile of expansion counties with all nonexpansion counties. The DID estimate was more prominent when comparing all expansion counties with the bottom 50th percentile of nonexpansion counties for change in the number of residents with low income and health insurance (−12.2 [95% CI, −16.0 to −8.4]; P < .001) compared with when the top 50th percentile of nonexpansion counties was used (−3.2 [95% CI, −5.7 to −0.8]; P = .01).

Table 3. Difference-in-Differences Analysis by Change in Number of Residents in Low-Income Strata With Health Insurance.

| Increase in Number of Residents With Health Insurancea | Mean (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Deaths per 100 000 Residents per y, Unadjusted | Difference-in-Differences Estimate | |||||

| Period Before Medicaid Expansion | Period After Medicaid Expansion | Unadjusted | P Value | Adjustedb | P Value | |

| Counties in Medicaid expansion states in top 50th percentile of increasec | 142.3 (129.0-155.6) | 142.2 (127.8-156.7) | −5.3 (−8.1 to −2.4) | .001 | −4.8 (−7.5 to −2.2) | .001 |

| All counties in Medicaid nonexpansion states | 176.2 (154.1-198.4) | 181.4 (158.4-204.4) | ||||

| Counties in Medicaid expansion states in bottom 50th percentile of increased | 162.8 (143.2-182.4) | 165.8 (147.2-184.5) | 0.3 (−2.3 to 2.9) | .81 | −1.3 (−4.0 to 1.4) | .34 |

| All counties in Medicaid nonexpansion states | 176.7 (153.9-199.5) | 179.5 (155.7-203.3) | ||||

| All counties in Medicaid expansion statese | 146.4 (132.3-160.4) | 146.2 (131.6-160.7) | −3.4 (−6.1 to −0.6) | .02 | −3.2 (−5.7 to −0.8) | .01 |

| Counties in Medicaid nonexpansion states in top 50th percentile of increasee | 165.4 (144.1-186.6) | 168.5 (146.6-190.4) | ||||

| All counties in Medicaid expansion statesf | 147.3 (133.1-161.6) | 147.0 (132.4-161.7) | −13.8 (−17.4 to −10.2) | .001 | −12.2 (−16.0 to −8.4) | .001 |

| Counties in Medicaid nonexpansion states in bottom 50th percentile of increasef | 223.0 (197.7-248.3) | 236.4 (210.1-262.8) | ||||

Change in number of residents with health insurance refers to change in the number of residents aged 40 to 64 years with health insurance with an income less than 138% of the federal poverty limit between 2010 and 2016.

Adjusted for 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification designation (metropolitan vs nonmetropolitan county), percentage of residents living in poverty, percentage of adults unemployed, inflation-adjusted median household income, percentage of residents aged 40 to 64 years who were female, percentage of residents aged 40 to 64 years who were black, percentage of residents aged 40 to 64 years who were Hispanic, percentage of adult residents with diabetes in 2010, percentage of adult residents with obesity in 2010, percentage of adult residents who smoke in 2010, number of primary care professionals per 100 000 residents, number of cardiologists per 100 000 residents, and percentage of residents aged 40 to 64 years with income less than 138% of the federal poverty limit with health insurance in 2010.

Expansion counties with a change in the number of residents with health insurance greater than 483 residents.

Expansion counties with a change in the number of residents with health insurance fewer than 483 residents.

Nonexpansion counties with a change in the number of residents with health insurance greater than 232 residents.

Nonexpansion counties with a change in the number of residents with health insurance fewer than 232 residents.

We also analyzed the cardiovascular mortality of residents aged 65 to 74 years over the same period. The adjusted DID estimate was −6.6 (95% CI, −16.2 to 3.1; P = .18; eTable 4 in the Supplement). Other sensitivity analyses had significant DID estimates, including ones that excluded all early-adopter and late-adopter states from the analysis (−3.6 [95% CI, −6.8 to −0.4]; P = .03) and ones using data aggregated at the state level, which included all deaths excluded from the county level analysis (−2.8 [95% CI, −5.1 to −0.5]; P = .02). The different sensitivity analyses are detailed in the online supplement (eMethods 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Counties in states that expanded Medicaid eligibility had a significantly smaller increase in age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality rates among residents aged 45 to 64 years after expansion compared with counties in nonexpansion states. Counties in expansion states had a mean of 4.3 fewer deaths per 100 000 residents per year than they would have had if they had followed the same trends as counties in nonexpansion states.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to show a population-level difference in rates of cardiovascular mortality among states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA. Such early changes in outcomes have also been also reported in other analyses of expansion in insurance coverage.5,7 However, these prior analyses were either focused on a single state (Massachusetts) or a specific chronic disease population (end-stage renal disease). The only randomized clinical trial of Medicaid expansion to date (the Oregon Health Study6) did not demonstrate significant improvements in cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension or hyperlipidemia.6 However, in addition to including the substantially larger number of people affected by Medicaid expansion under the ACA, this study focused on middle-aged adults, an age group which represented around 28% of the Oregon Health study6 population and one with a higher burden of cardiovascular disease than younger adults. Given the small absolute differences in mortality between expansion and nonexpansion counties observed in this analysis, it is possible that such differences would not be observed in a study with a smaller sample size.

Studies of inpatient outcomes and quality of care of patients with heart failure and myocardial infarction did not show a significant association with Medicaid expansion.14,15 This suggests that a possible influence of Medicaid expansion could be in the outpatient setting or access to care. One prior study27 noted an association between lack of insurance coverage and delays in seeking emergency care by patients with myocardial infarction. Medicaid expansion has also been associated with higher rates of provision of cardiovascular medications, such as aspirin and better diabetes control.28 There is also evidence of an increase in rates of coronary artery bypass graft surgery associated with Medicaid expansion.29 Although we noted a stronger association between Medicaid expansion and cardiovascular mortality in the counties where there was a greater increase in the number of individuals gaining insurance coverage, there may be other indirect mechanisms by which expansion may be associated with the observations noted. The DID point estimate for individuals 65 to 74 years old suggests a possible beneficial association even for a population not directly affected by Medicaid expansion and the potential existence of a spillover phenomenon. This may be mediated by mechanisms such as strengthening of the financial health of institutions that provide care to individuals with lower incomes throughout the age spectrum (eg, community health centers, safety net hospitals).30,31 Additionally, changes in insurance coverage in a population have been associated with access to health care and the quality of care received even by the insured population.32

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. Given the observational nature of the study, we are not able to make a causal association between expansion of Medicaid eligibility and differences in the cardiovascular mortality rates between the 2 groups of counties. It is possible that there were other unmeasured time-varying factors that can explain the observed association. Along with expanding eligibility for Medicaid, it is possible that other aspects of the ACA were implemented more in expansion states. Although the primary target of Medicaid expansion was adults with low income, the outcome measure is for residents of all income categories. However, we do observe a stronger association between Medicaid expansion and cardiovascular mortality in counties with more residents in low income strata. The primary outcome is mortality from diseases of the circulatory system, which includes several different disorders. Although in a sensitivity analysis we did analyze a subset of these disorders, we did not analyze individual diseases to elucidate which ones are driving the overall mortality trend, owing to the small number of deaths from any individual cause. The primary analysis excluded counties with fewer than 10 deaths per year; however, a sensitivity analysis with outcome and covariates aggregated at the state level, which included all deaths in a state, had a significant association as well.

Conclusions

This study shows an association between Medicaid expansion and differences in cardiovascular mortality rates between expansion and nonexpansion states for middle-aged adults. Given the high burden of cardiovascular risk factors among individuals without insurance and those with lower socioeconomic status, these results may be a consideration as policymakers debate further changes to eligibility and expansion of Medicaid.

eMethods 1. Difference-in-Differences Model.

eMethods 2. Interaction between expansion status and year.

eMethods 3. Sensitivity Analyses.

eTable 1. Percentage of 40-64 Year Old Residents without Health Insurance Coverage.

eTable 2. Mean Age-Adjusted Cardiovascular Mortality Rates for 45-64 Year Old Residents (Deaths per 100 000 Residents per year) by Year.

eTable 3. Interaction Between Expansion Status and Year.

eTable 4. Pre-Medicaid Expansion Parallel Trends Assumption (2010-2013).

eTable 5. Difference-in-Differences Sensitivity Analyses.

References

- 1.Soni A, Burns ME, Dague L, Simon KI. Medicaid expansion and state trends in supplemental security income program participation. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1485-1488. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommers BD, Fry CE, Blendon RJ, Epstein AM. New approaches in Medicaid: work requirements, health savings accounts, and health care access. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1099-1108. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silvestri DM, Holland ML, Ross JS. State-level population estimates of individuals subject to and not meeting proposed Medicaid work requirements. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1552-1555. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1025-1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommers BD, Long SK, Baicker K. Changes in mortality after Massachusetts health care reform. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(9):668-669. doi: 10.7326/L15-5085-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al. ; Oregon Health Study Group . The Oregon experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713-1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swaminathan S, Sommers BD, Thorsness R, Mehrotra R, Lee Y, Trivedi AN. Association of Medicaid expansion with 1-year mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. JAMA. 2018;320(21):2242-2250. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.16504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stringhini S, Carmeli C, Jokela M, et al. ; LIFEPATH consortium . Socioeconomic status and the 25 × 25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: a multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1·7 million men and women. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1229-1237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32380-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks EL, Preis SR, Hwang S-J, et al. Health insurance and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am J Med. 2010;123(8):741-747. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Fonseca VA, McPhaul MJ. Surge in newly identified diabetes among medicaid patients in 2014 within medicaid expansion States under the affordable care act. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(5):833-837. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh A, Simon K, Sommers B The effect of state Medicaid expansions on prescription drug use: evidence from the Affordable Care Act. http://www.nber.org/papers/w23044. Accessed December 1, 2018.

- 12.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after Medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1501-1509. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhabue E, Pool LR, Yancy CW, Greenland P, Lloyd-Jones D. Association of state Medicaid expansion with rate of uninsured hospitalizations for major cardiovascular events, 2009-2014. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181296. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wadhera RK, Bhatt DL, Wang TY, et al. Association of state Medicaid expansion with quality of care and outcomes for low-income patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(2):120-127. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wadhera RK, Joynt Maddox KE, Fonarow GC, et al. Association of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion with care quality and outcomes for low-income patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(7):e004729. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevalence of coronary heart disease—United States, 2006-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(40):1377-1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics Compressed mortality file 1999-2016 on CDC WONDER online database; 2017. http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html. Accessed November 4, 2018.

- 18.US Census Bureau Small area income and poverty estimates (SAIPE) program. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/saipe.html. Accessed November 5, 2018.

- 19.US Census Bureau Population and housing unit estimates. https://www.census.gov/popest. Accessed November 5, 2018.

- 20.Bureau of Labor Statistics Local area unemployment statistics home page. https://www.bls.gov/lau/. Published July 19, 2008. Accessed November 5, 2018.

- 21.US Census Bureau Small area health insurance estimates (SAHIE) program. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sahie.html. Accessed November 5, 2018.

- 22.Health Resources & Services Administration Area health resources files. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf. Accessed November 5, 2018.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_data.htm. Accessed November 5, 2018.

- 24.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q J Econ. 2004;119:249-275. doi: 10.1162/003355304772839588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/. Published September 11, 2018. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- 26.Wooldridge JM. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smolderen KG, Spertus JA, Nallamothu BK, et al. Health care insurance, financial concerns in accessing care, and delays to hospital presentation in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2010;303(14):1392-1400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole MB, Galárraga O, Wilson IB, Wright B, Trivedi AN. At federally funded health centers, Medicaid expansion was associated with improved wuality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):40-48. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charles EJ, Johnston LE, Herbert MA, et al. ; Investigators for the Virginia Cardiac Services Quality Initiative and the Michigan Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeons Quality Collaborative . Impact of Medicaid expansion on cardiac surgery volume and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(4):1251-1258. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.03.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dranove D, Garthwaite C, Ody C. Uncompensated care decreased at hospitals in Medicaid expansion states but not at hospitals in nonexpansion States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1471-1479. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Commonwealth Fund The role of Medicaid expansion in care delivery at community health centers. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/apr/role-medicaid-expansion-care-delivery-FQHCs. Published April 4, 2019. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- 32.Pauly MV, Pagán JA. Spillovers and vulnerability: the case of community uninsurance. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(5):1304-1314. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Difference-in-Differences Model.

eMethods 2. Interaction between expansion status and year.

eMethods 3. Sensitivity Analyses.

eTable 1. Percentage of 40-64 Year Old Residents without Health Insurance Coverage.

eTable 2. Mean Age-Adjusted Cardiovascular Mortality Rates for 45-64 Year Old Residents (Deaths per 100 000 Residents per year) by Year.

eTable 3. Interaction Between Expansion Status and Year.

eTable 4. Pre-Medicaid Expansion Parallel Trends Assumption (2010-2013).

eTable 5. Difference-in-Differences Sensitivity Analyses.