Abstract

Background:

Fulvestrant 500 mg (F500) is the most active endocrine single agent in hormone receptor-positive (HR+)/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Few data are available regarding the effectiveness of the drug in a real-world setting.

Patients and methods:

This prospective, multicenter cohort study aimed to describe the patterns of treatment and performance of F500 in a large population of unselected women with MBC, focusing on potential prognostic or predictive factors for disease outcome and response. The primary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS) and clinical benefit rate.

Results:

From January 2011 to December 2015, 490 consecutive patients treated with F500 were enrolled. Overall, three different cohorts were identified and analyzed: the first received F500 after progression from previous chemotherapy (CT) or endocrine therapy; the second received the drug for de novo metastatic disease; and the third was treated as maintenance following disease stabilization or a response from a previous CT line. Median overall survival (OS) in the whole population was 26.8 months, ranging from 32.4 in first line to 22.0 and 13.7 months in second line and subsequent lines, respectively. Both the presence of liver metastasis and the treatment line were significantly associated with a worse PFS, while only the presence of liver metastasis maintained its predictive role for OS in multivariate analysis.

Conclusions:

The effectiveness of F500 was detected in patients treated both upon disease progression and as maintenance. The relevant endocrine sensitivity of 80% of patients included in the study could probably explain the good results observed in terms of outcome.

Keywords: endocrine therapy, fulvestrant 500 mg, metastatic breast cancer, real life

Introduction

Breast cancer, one of the three most common malignancies worldwide, is a disease strongly related with age, with the highest incidence among elderly, postmenopausal women.1 Approximately 70–80% of breast cancers are estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PgR)-positive and thus potentially sensitive to endocrine therapy (ET). The main international guidelines endorse ET as the preferred first-line option for hormone receptor-positive (HR+) disease in postmenopausal women, even in the presence of visceral disease (but not in cases of visceral crisis or concern/proof of endocrine resistance). At some point of her clinical history, every woman with HR+/HER2 metastatic breast cancer (MBC) will receive one or more ET lines in the context of a sequential strategy.2 The choice of the upfront and subsequent agents mainly depends on the type of adjuvant ET as well as the disease-free interval from its completion; these can be aromatase inhibitors (AIs), tamoxifen, or fulvestrant.3 However, almost all women with initially endocrine-sensitive disease will develop a resistance to ET, either as an early failure (de novo resistance), or as a progression after an initial response (acquired resistance).4 The optimal sequence of single endocrine agents and combinations with targeted agents is yet to be defined and is a research priority.

Fulvestrant (Faslodex®) is an anti-estrogen that belongs to the selective ER down-regulators class and is characterized by a novel mechanism of action, being a pure antagonist of ER, without partial agonist activity.5 Preclinical and clinical studies have also demonstrated the lack of cross-resistance between fulvestrant and other hormonal treatments.6,7

According to the suggested concept of the dose-dependent activity of fulvestrant,8 the phase III study CONFIRM randomized patients with MBC, progressing after previous endocrine treatment with tamoxifen or AIs, to receive fulvestrant 500 mg (F500) versus 250 mg (F250). F500 significantly improved progression-free-survival (PFS) compared with F250 as well as the overall response rate (ORR) and clinical benefit rate (CBR)9; this study led to the adoption of F500 for the treatment of HR+ postmenopausal women with disease progression following anti-estrogen therapy. An unplanned survival analysis showed that F500 had a favorable hazard ratio 0.81 (p = 0.016) compared with F250 in terms of the risk of death, with an absolute 4.1 month increase in median overall survival (OS).10

The phase II trial FIRST randomized women with previously untreated disease to receive F500 versus anastrozole. As for the primary endpoint of CBR, F500 and anastrozole proved to be similar, as well as for ORR11,12; notably, the median time to progression and OS significantly favored F500.13 Finally, the phase III study FALCON confirmed the superiority of F500 over anastrozole as first-line therapy for HR+ untreated metastatic disease.14

The recently published randomized, phase III, placebo-controlled, PALOMA-3 trial demonstrated that the addition of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)4/6 inhibitor palbociclib to F500, in women relapsed or progressed after prior ET, was able to provide a significant benefit in PFS and also improved quality of life (QoL).15,16

Beside randomized clinical trials, so far, few data are available regarding the effectiveness and safety of F500 in the real-life setting. The aim of this observational, prospective, longitudinal cohort study was to describe the patterns of treatment and performance of F500 in a large population of unselected women with MBC, with a focus on the potential prognostic or predictive factors for disease outcome and treatment response.

Patients and methods

Study design

This is an open-label, longitudinal, prospective, multicenter cohort study conducted from January 2011 to December 2015 at three oncology institutions in Northern Italy (two university hospitals, one community hospital). All of them usually treat more than 150 new cases of breast cancer per year and are representative of the geographical area. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Coordinator Center (ICS Maugeri IRCCS), protocol no. 2086 CE; all patients provided written informed consent for the inclusion in the study, analysis, and anonymized publication of clinical data.

Study population

Eligible patients were postmenopausal women with MBC and histologically proven HR+ disease (defined as ER or PgR >1% by immunohistochemistry [IHC]), and candidates to receive F500 following anti-estrogen therapy, either in the adjuvant or metastatic setting, according to their contingent clinical situation. Additional inclusion criteria were HER2 negative (HER2−) disease (immunohistochemistry 0–1 or IHC 2, confirmed as fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) negative), measurable or evaluable lesions according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria, version 1.1,17 and a life expectancy of at least 4 months. They were also required to have adequate bone marrow, hepatic, renal function, according to clinical practice guidelines for antineoplastic drug administration; no prespecified limits were set for blood tests in order to have the closest situation to clinical practice. Previous chemotherapy (CT) or ET for metastatic disease was allowed. Data collection started from the administration of the first dose of F500 and included the patients’ performance status and age at study entry, disease characteristics, HR and HER2 status, sites and number of metastases, and tumor biology, as well as previous therapies received in the adjuvant and metastatic setting.

Treatment plan

Treatment was administered until documented progressive disease (PD), unacceptable toxicity, or patient refusal and was given in an outpatient setting, according to the officially approved national guidelines (500 mg i.m. on days 0, 14, 28; every 4 weeks thereafter). The tumor assessment was performed approximately every 4 months, unless there were clinical signs of PD, according to clinical practice and the physician’s approach, as well as to the sites of metastatic disease. A complete blood count and organ function test was performed before each cycle; no prespecified dose delays or modifications were planned.

Statistical analysis

The primary aim of the study was to analyze the effectiveness of F500 in terms of PFS and CBR. PFS was defined as the time interval from the start of therapy with F500 to the date of PD; CBR was defined as the percentage of patients experiencing a complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or stable disease (SD) lasting 6 months or more. Clinical responses were evaluated according to the RECIST criteria, version 1.1.

Secondary aims included the evaluation of safety events and OS. Toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria (NCI-CTCAE), version 4.18 OS was calculated as the interval from therapy start with F500 to the date of death or of last follow-up evaluation. A subgroup analysis was performed to identify potential prognostic or predictive factors for disease outcome and treatment response. Population characteristics and treatment-related variables were analyzed using standard descriptive statistical methods. The Chi-squared test was applied to categorical variables. The level of significance of statistical tests was set at p < 0.05. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The Cox regression model was used for univariate and multivariate analysis.

As for subgroup analysis, the variables investigated were: age (>65 versus ⩽65 years); tumor stage at disease presentation (IV versus I–III); disease-free interval (DFI) from adjuvant treatment (>24 months versus ⩽24 months); number of metastatic sites (>2 versus ⩽2); liver involvement (yes versus no); prior CT before F500 (yes versus no); line of treatment with F500 (⩾3 versus 1–2); and treatment setting (treatment at PD versus maintenance).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 490 patients met the research criteria and 480 were considered for data analysis. Overall, 10 patients were excluded for incomplete or missing data, while all women were evaluable for toxicity, as described in the patient flow diagram (Figure 1). Clinical and demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. The median age at study entry was 66 years (range 56–81); 39.2% of the patients were aged 65 years or less. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status was 0–1 in almost all patients (91.6%). As for patients with metachronous disease progression (79% of the evaluable population), the median DFI was 64 months (range 18–196). About 30% of these patients had received an AI, with or without tamoxifen, in the adjuvant setting. As for the metastatic setting, 24% of patients had received F500 as a first-line option, while 41% had received CT alone or in sequence with a hormonal agent (an AI in 95% of cases). A total of 101 patients had a metastatic disease ab initio (21% of the overall population).

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Enrolled/evaluable | 490/480 | 97.9 |

| Median age, years (range) | 66 (56–81) | |

| ⩽65 years | 188 | 39.2 |

| >65 years | 292 | 60.8 |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 245 | 51 |

| 1 | 195 | 40.6 |

| 2 | 40 | 8.3 |

| Receptor status | ||

| ER+/PgR+ | 306 | 63.7 |

| ER+/PgR− | 99 | 20.6 |

| ER−/PgR+ | 48 | 10 |

| ICH HER2-neu+ (FISH negative) | 27 | 5.6 |

| Prior adjuvant therapy | ||

| tamoxifen | 148 | 30.8 |

| aromatase inhibitors | 90 | 18.7 |

| tamoxifen ⩾ aromatase inhibitors | 55 | 11.4 |

| chemotherapy + hormone therapy | 86 | 17.9 |

| Median DFI, months (range) | 64 (18–196) | |

| ⩽24 months | 56 | 22.1 |

| >24 months | 323 | 77.9 |

| Prior therapy for metastatic disease | ||

| None | 115 | 23.9 |

| hormone therapy | 168 | 35 |

| chemotherapy | 138 | 28.7 |

| Chemotherapy + hormone therapy | 59 | 12.2 |

| Prior hormone therapy for metastatic disease | ||

| anastrozole | 113 | 49.7 |

| letrozole | 47 | 20.7 |

| exemestane | 52 | 22.9 |

| tamoxifen | 15 | 6.6 |

| De novo metastatic disease | 101 | 21 |

| Dominant metastatic sites | ||

| Bone | 270 | 56.2 |

| Liver | 96 | 20 |

| Lung | 60 | 12.5 |

| nodes/soft tissues/skin | 54 | 11.2 |

| Number of metastatic sites | ||

| 1 | 302 | 62.9 |

| 2 | 109 | 22.7 |

| ⩾3 | 69 | 14.3 |

DFI, disease-free interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ER, estrogen receptor; FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization; ICH HER2-neu, immunohistochemistry HER2-neu; PgR, progesterone receptor.

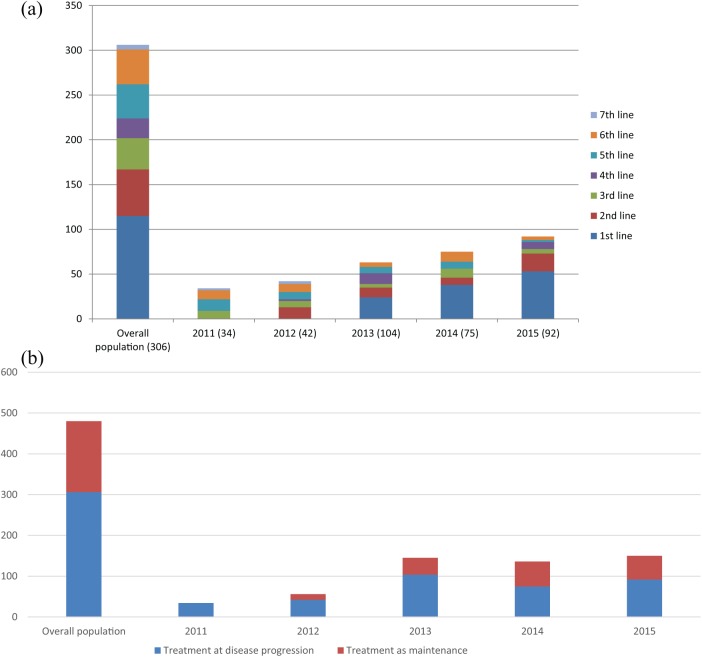

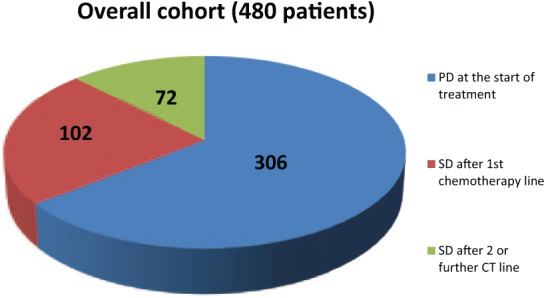

The majority of patients had metastases involving one or two organs (62.9% and 22.7% respectively). In addition, 32.5% of patients had visceral involvement, whereas 56.2% had bone-only metastases. A total of 306 patients received F500 after PD, 102 and 72 were treated as maintenance therapy following first or second-line CT, respectively (Figure 2). As shown in Figure 3, treatment patterns of F500 interestingly changed over the study period, with an increasing proportion of women receiving the drug as an always earlier line of therapy and as a maintenance strategy.

Figure 2.

Patterns of treatment with F500 in the whole population.

CT: chemotherapy; F500, fulvestrant 500 mg; PD: progressive disease; SD: stable disease.

Figure 3.

Patterns of treatment with F500 across the study period.

(a) The increasing proportion of patients receiving F500 in the first and second line of treatment across the study period (compared with those treated in subsequent lines).

(b) The increasing proportion of patients receiving F500 as a maintenance strategy across the study period (compared with those treated at disease progression).

F500, fulvestrant 500 mg.

Treatment activity

A minimum of 6 cycles of F500 was administered to all patients, with a median number of 14 (range 6–28). According to the treatment setting, patients who received F500 after PD had an ORR of 17.6%, with a CR of 3.4%. Disease stabilization was achieved in 122 patients, lasting more than 24 weeks in 74 of them (36.0%), for an overall CBR of 53.6% (95% CI 0.46–0.60). A total of 47 patients (22.9%) experienced PD during F500 treatment. Within the population receiving the drug for de novo metastatic disease, an ORR of 47.5% was observed, with 44.6% of PR and 24.8% of SD ⩾24 weeks, for an overall CBR of 72.3%. As for the women treated with F500 as a maintenance strategy, a slight difference was observed between those treated following disease stabilization or response in terms of both ORR (4.5% and 8.3%, respectively) and CBR (43.9% and 56.5% respectively). The median time to response was 6 months (range 4–9).

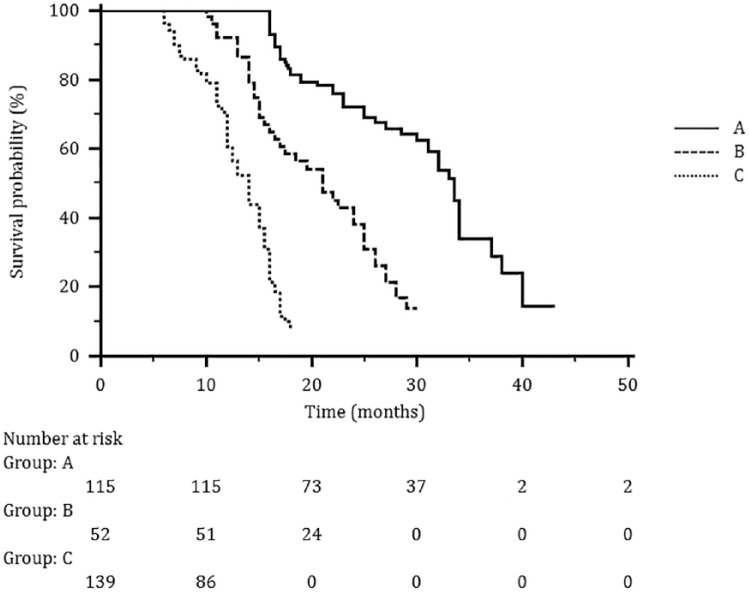

At a median follow up of 35 months (range 18–56), no difference in median PFS was observed in patients receiving the drug at PD or as a maintenance (11.6 and 11.1 months, respectively). When analyzed according to the treatment line (1st, 2nd, ⩾3rd) median PFS values were significantly prolonged when F500 was administrated as a first-line treatment (12.5 months), to decrease progressively in second and subsequent lines of treatment (11.4 and 6.2 months respectively). By contrast, in the maintenance setting, similar PFS values were observed among subgroups of patients treated at disease stabilization or following a response (11.2 and 10.9, respectively; Table 2). Median OS in the whole population was 26.8 months, ranging from 32.4 months in the first line to 22.0 and 13.7 months in second and subsequent lines, respectively (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Treatment activity in the whole population (480 evaluable patients).

| F500 after PD | F500 as maintenance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD after prior therapy (n = 205) | n | % | 95% CI | After OR (n = 108) | n | % | 95% CI |

| Overall response rate | 36 | 17.6 | 0.13–0.23 | Overall response rate | 9 | 8.3 | 0.04–0.15 |

| Complete response | 7 | 3.4 | 0.01–0.06 | Complete response | 1 | 0.9 | 0.002–0.05 |

| Partial response | 29 | 14.1 | 0.10–0.19 | Partial response | 8 | 7.4 | 0.03–0.13 |

| SD ⩾ 24 weeks | 74 | 36.0 | 0.29–0.42 | SD ⩾ 24 weeks | 52 | 48.1 | 0.39–0.57 |

| SD < 24 weeks | 48 | 23.4 | 0.18–0.29 | SD < 24 weeks | 18 | 16.7 | 0.10–0.24 |

| PD | 47 | 22.9 | 0.17–0.29 | PD | 29 | 26.9 | 0.19–0.35 |

| Clinical benefit rate | 110 | 53.6 | 0.46–0.60 | Clinical benefit rate | 61 | 56.5 | 0.47–0.65 |

| De novo metastatic disease (n = 101) | After SD (n = 66) | ||||||

| Overall response rate | 48 | 47.5 | 0.38–0.57 | Overall response rate | |||

| Complete response | 3 | 3.0 | 0.01–0.08 | Complete response | – | – | – |

| Partial response | 45 | 44.6 | 035–0.54 | Partial response | 3 | 4.5 | 0.01–0.12 |

| SD ⩾ 24 weeks | 25 | 24.8 | 0.17–0.34 | SD ⩾ 24 weeks | 26 | 39.4 | 0.28–0.51 |

| SD < 24 weeks | 8 | 7.9 | 0.04–0.14 | SD < 24 weeks | 10 | 15.2 | 0.08–0.25 |

| PD | 12 | 11.9 | 0.06–0.19 | PD | 17 | 25.8 | 0.16–0.37 |

| Clinical benefit rate | 73 | 72.3 | 0.62–0.80 | Clinical benefit rate | 29 | 43.9 | 0.32–0.55 |

| Progression-free survival, months | |||||||

| Median | Range | Median | Range | ||||

| F500 after PD | F500 as maintenance | ||||||

| Overall population (n = 306) | 11.6 | 8.1–16.2 | Overall population (n = 174) | 11.1 | 8.3–14.8 | ||

| First line | 12.5 | 10.216.2 | After OR | 10.9 | 9.1–13.6 | ||

| Second line | 11.4 | 8.8–12.2 | After SD | 11.2 | 7.4–12.2 | ||

| ⩾3 lines | 6.2 | 4.8–9.2 | |||||

CI, confidence interval; F500, fulvestrant 500 mg; OR, objective response; PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

Figure 4.

The median OS in the whole population according to treatment line: (a) first line; (b) second line; (c) subsequent lines.

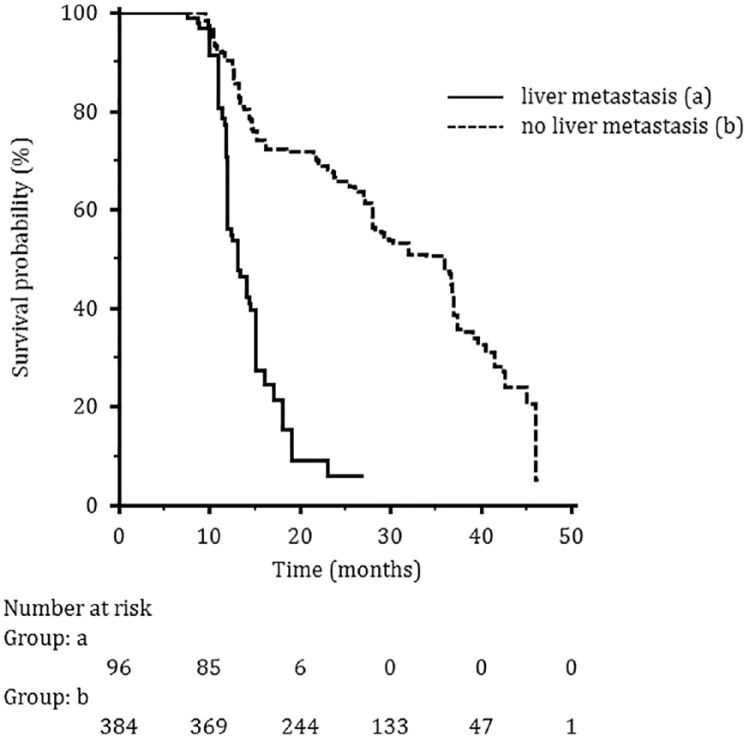

A subgroup analysis was performed in order to identify variables of potential predictive or prognostic value. Both the presence of liver metastasis and the treatment line were significantly associated with a worse PFS at the univariate analysis, and the difference was maintained in the multivariate analysis. For OS, the presence of liver metastasis, previous CT for metastatic disease and the F500 treatment line were negatively associated with a worse OS, but only the presence of liver metastasis maintained its negative predictive role also in multivariate analysis (Table 3 and Figure 5).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for progression-free survival and overall survival.

| Progression-free survival | Overall survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value |

| Age (>65 versus ⩽65 years) | 0.89 (0.68–1.15) | 0.371 | 0.98 (0.74–1.29) | 0.873 | 1.35 (0.83–2.2) | 0.229 | 2 (0.96–3.43) | 0.072 |

| Stage (IV versus ⩽ III) | 0.93 (0.64–1.34) | 0.695 | 1.26 (0.81–1.97) | 0.308 | 0.94 (0.48–1.83) | 0.851 | 0.79 (0.34–1.81) | 0.577 |

| Number of metastatic sites (>2 versus ⩽2) | 1.29 (0.95–1.76) | 0.102 | 1.01 (0.72–1.43) | 0.933 | 1.82 (1.09–3.02) | 0.021 | 1.03 (0.59–1.82) | 0.913 |

| Liver metastases (yes versus no) | 2.23 (1.65–3.01) | <0.001 | 2.16 (1.54–3.04) | <0.001 | 4.30 (2.70–6.84) | < 0.001 | 4.11 (2.36–7.14) | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy for metastatic disease (yes versus no) | 1.48 (1.14–1.93) | 0.004 | 0.93 (0.65–1.32) | 0.667 | 2.56 (1.47–4.47) | 0.001 | 1.28 (0.59–2.76) | 0.537 |

| F500 treatment line (⩾3 versus 1–2) | 2.11 (1.52–2.93) | < 0.001 | 2.04 (1.36–3.05) | 0.001 | 2.68 (1.54–4.68) | 0.001 | 2.04 (1–4.17) | 0.051 |

| F500 treatment setting (at PD versus maintenance) | 0.75 (0.54–1.21) | 0.503 | 0.87 (0.64–1.31) | 0.723 | 1.25 (0.73–2.24) | 0.462 | 1.51 (0.83–1.97) | 0.236 |

CI, confidence interval; F500, fulvestrant 500 mg; HR, hazard ratio; PD, progressive disease.

Figure 5.

Median overall survival according to visceral involvement: (a) patients with liver metastasis; (b) patients without liver metastasis.

Treatment safety

The median drug exposure was 14.6 months (range 5.6–26.1). Overall, treatment was well tolerated with good compliance in the outpatient setting. No severe drug-related adverse events were recorded; in no case was treatment delayed or interrupted and no death occurred because of toxicity. As expected, the most common adverse events were joint disorders, hot flushes, and myalgia. No substantial difference in incidence and severity of adverse events was seen between the two groups of women receiving the drug at progression of disease or as maintenance therapy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Treatment-related adverse events (480 evaluable patients).

| F500 at progression disease (n=306) | F500 as maintenance (n=174) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with any adverse event | 208 (67.9%) | 113 (64.9%) | ||||||

| NCI-CTCAE Toxicity | Grade 1 N (%) |

Grade 2 N (%) |

Grade 1 N (%) |

Grade 2 N (%) |

||||

| Non-hematological Joint disorders Hot flushes Myalgia Fatigue Nausea Back pain Dyspnoea Hypertension Injection site reactions Weight gain Peripheral oedema |

31 20 14 12 8 9 7 11 13 5 |

(10.1) (6.5) (4.5) (3.9) (2.6) (2.9) (2.2) (3.5) (4.2) (1.6) |

10 12 8 4 2 4 6 8 10 - |

(3.2) (3.9) (2.6) (6.2) (0.6) (1.3) (1.9) (2.6) (3.2) - |

19 10 9 10 6 2 3 8 5 2 |

(10.9) (5.7) (5.1) (5.7) (3.4) (1.1) (1.7) (4.5) (2.8) (1.1) |

4 8 2 - 3 3 1 5 6 - |

(2.2) (4.5) (1.1) - (1.7) (1.7) (0.5) (2.8) (3.4) - |

| Hematological | ||||||||

| Anemia | 3 | (0.9) | - | - | 2 | (1.1) | - | - |

| Leucopenia | 2 | (0.6) | 2 | (1.1) | - | |||

| Alanine aminotransferase increase | 5 | (1.6) | - | - | - | - | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase increase | 4 | (1.3) | - | - | 3 | (1.7) | - | - |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to verify the performance of F500 in a real-world setting, while analyzing the patterns of treatment and the physicians’ actual prescription attitude. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the experience reported here is the largest real-life series of unselected patients treated with F500 over a 5-year time span. In such a heterogeneous cohort we can identify at least three different clinical situations. The first scenario involves women receiving the drug at disease progression after prior adjuvant or first-line treatment (n = 205). In this population, a median PFS of 11.6 months and a CBR of 54% were observed. These results compare favorably with the values of 45.6% CBR and median PFS of 6.5 months reported by the phase III CONFIRM trial, in which the most represented subgroup consisted of patients relapsed on adjuvant ET or presenting with de novo advanced disease progressing on the first line.9,10 By contrast, in our population, 139 (68%) out of 205 patients received F500 beyond the third line and up to the seventh line of treatment; in addition, 64% of them had previously been treated with CT alone or in sequence with different endocrine agents.

A second picture emerges with regards to women receiving the drug as a first-line treatment option: our data mainly refer to patients with de novo metastatic disease, who are recognized as having relatively good prognosis when compared with those with recurring disease.19,20 The observed median PFS of 12.5 months with a CBR of 72.2% are in keeping with those of the FALCON trial, which reported a median PFS of 16.6 months in ET-naïve patients diagnosed with MBC from less than 1 year, and among which only one-third had previously received CT.14 Although the results of the FALCON study suggest a particular sensitivity to F500 in de novo stage IV disease, caution should be used when interpreting these results, because this study was not powered to assess this question. We agree with the hypothesis that metastatic disease with visceral involvement indicates not only a more aggressive behavior, but also a larger tumor burden and heterogeneous estrogen sensitivity.21 In this special population, a combination of F500 with other endocrine or target agents might be appropriate.16,22 On the other hand, a recently reported prespecified subgroup analysis across the PALOMA-3 population showed that the presence of visceral metastases maintained an independent negative prognostic value, also when F500 was combined with palbociclib.16

Of interest in our study, is the analysis of patients with liver metastasis: a poorer outcome in terms of both PFS and OS was observed at statistical analysis, with liver involvement resulting in the only one negative prognostic factor for disease outcome at multivariate analysis. These findings address the still open question on the potential higher benefit achievable with endocrine single agents in women without visceral metastases, for which ET is widely considered to be the best therapeutic strategy.23–26

An additional, an element of heterogeneity in our experience regards the third and last clinical situation, concerning the use of F500 as a maintenance strategy. In daily clinical practice, switching to ET during CT is a commonly employed strategy, aiming to reduce treatment side effects without compromising the disease outcome. Such an approach is based on the biological rationale of the control of the regrowth of hormone-dependent clones after maximum cytoreduction obtained by CT27 and is also supported by the European Consensus Guidelines with a level of evidence of 1C.2 In our series, 36% of enrolled women received the drug as a maintenance ET following first- or second-line CT (102 and 72 patients, respectively): the observed median PFS was similar to that of patients treated at PD (11.1 and 11.6 months, respectively), while a slight difference between patients treated following disease stabilization or documented response was observed in terms of both ORR (4.5% and 8.3%, respectively) and CBR (43.9% and 56.5%, respectively). Data on this topic are scarce in the literature, and only one prospective randomized study with maintenance medroxyprogesterone is available.28 The results of a large retrospective study on 934 MBC patients receiving ET after response or stabilization following first-line CT compare favorably with ours, because this strategy seemed related to a better PFS and OS. As in our population, the achieved benefit appeared of the same magnitude in patients achieving OR or SD.29 Such an approach reflects the modern continuum of MBC management, aiming towards stable and prolonged disease control instead of an objective and measurable response throughout an appropriate agent sequencing.

Our findings add information to interpreting patterns of treatment with F500 in a large unselected population of women with HR+/HER2− MBC, within the limits of an uncontrolled study of an observational nature, lacking in comparator and QoL data. As is known, the strength of real-life experiences is based on the possibility to verify the reproducibility of evidence-based data in daily clinical practice. The available real-world experiences, although not fully comparable for population heterogeneity, treatment line, and clinical context, globally confirm that F500 is an effective and well-tolerated therapy for postmenopausal HR+/HER2− MBC.30–34 The most recently reported study described a CBR of 61% on 160 patients treated with F500 in different lines, with a PFS of 7 months and an OS of 35 months; as in our experience, visceral involvement had a prognostic value for PFS, whereas endocrine sensitivity and upfront metastatic disease negatively correlated with OS. As expected, patients who had received previous first-line ET for advanced disease exhibited a worse outcome and a lower CBR, while patients with lower body mass index had a PFS advantage.35,36 In our experience, the use of F500 in early disease phases translated into a better PFS and OS, with a statistically significant impact on OS at multivariate analysis. Interestingly, a progressive shift of the physician’s attitude to prescribe F500 as an always earlier treatment line was observed across the study period, somehow preceding the subsequent evidence-based data.

The increasing number of options for ET and ET-based therapies is challenging the traditional approach to agent sequencing for HR+ MBC. In this complex scenario, the best agent prioritization as well as the patient selection, from both a biological and clinical point of view, remain at least partially undefined, because of the lack of ad hoc designed randomized clinical trials and reliable molecular biomarkers, particularly to effectively identify endocrine sensitivity.37,38

At present, the critical issue is: which patient can be treated with a single drug, and which one requires a combination treatment? The hard question remains unanswered, because an impact on OS is still unproven for the combination regimen, and the clinical criteria currently adopted to patient selection are clearly inadequate.39

In this view, strategies to overcome resistance are of increasing interest, as recently reported in the TREND study, suggesting the addition of a CDK inhibitor at progression on ET has the potential to reverse endocrine resistance in patients with a history of previous durable response to ET itself.40

Ultimately, additional determinants of choice of the best treatment strategy should be considered, such as pharmacoeconomic issues, regulatory drug availability, toxicity issues, patient compliance, and attitude to long-term treatment adherence.

Conclusion

Our real-life experience confirms that F500 can be safely offered to most women with HR+/HER2− MBC, producing clinical activity both in patients treated upon PD and in those receiving the drug as a maintenance strategy. In addition, the search for potential predictive or prognostic factors showed that neither tumor-related nor patient-related variables significantly affected the probability of response, thus suggesting a good performance of the drug in the various clinical situations. The statistically significant correlation found between an earlier administration of the drug and a better clinical outcome adds information for daily decision-making, aiming for a personalized approach to treatment selection.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Raffaella Palumbo, Medical Oncology Unit, IRCCS-ICS Maugeri, Pavia, Italy.

Federico Sottotetti, Medical Oncology Unit, IRCCS-ICS Maugeri, Via Maugeri 10, 27100 Pavia, Italy.

Erica Quaquarini, Medical Oncology Unit, IRCCS-ICS Maugeri, Pavia, Italy; Experimental Medicine, University of Pavia, Italy.

Anna Gambaro, Medical Oncology, Luigi Sacco Hospital, Milano, Italy.

Antonella Ferzi, Medical Oncology, Legnano Hospital, Legnano, Italy.

Barbara Tagliaferri, Medical Oncology Unit, IRCCS-ICS Maugeri, Pavia, Italy.

Cristina Teragni, Medical Oncology Unit, IRCCS-ICS Maugeri, Pavia, Italy.

Luca Licata, Medical Oncology Unit, IRCCS-ICS Maugeri, Pavia, Italy.

Francesco Serra, Medical Oncology Unit, IRCCS-ICS Maugeri, Pavia, Italy.

Pietro Lapidari, Medical Oncology Unit, IRCCS-ICS Maugeri, Pavia, Italy.

Antonio Bernardo, Medical Oncology Unit, IRCCS-ICS Maugeri, Pavia, Italy.

References

- 1. Stat Fact Sheets SE. Female breast cancer, https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html (2018, accessed 26 May 2018).

- 2. Cardoso F, Costa A, Senkus E, et al. 3rd ESO–ESMO international consensus guidelines for Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC 3). Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 16–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reinert T, Barrios H. Optimal management of hormone receptor positive metastatic breast cancer in 2016. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2015; 7: 304–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Augereau P, Patsouris A, Bourbouloux E, et al. Hormonoresistance in advanced breast cancer: a new revolution in endocrine therapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2017; 9: 335–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robertson JFR, Nicholson RI, Bundred NJ, et al. Comparison of the Short-Term Biological Effects of 7α-[9- (4, 4, 5, 5, 5-pentafluoropentylsulfinyl) - nonyl] estra- 1, 3, 5, (10) – triene - 3, 17β-diol (Faslodex) Tamoxifen in Postmenopausal Women with Primary Breast Cancer. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 6739–6746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Osborne CK, Wakeling A, Nicholson RI. Fulvestrant: an oestrogen receptor antagonist with a novel mechanism of action. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: S2–S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nagaraj G, Ma C. Revisiting the estrogen receptor pathway and its role in endocrine therapy for postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015; 150: 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robertson JFR. Fulvestrant (Faslodex) – how to make a good drug better. Oncologist 2007; 12: 774–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Leo A, Jerusalem G, Petruzelka L, et al. Results of the CONFIRM phase III trial comparing fulvestrant 250 mg with fulvestrant 500 mg in postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 4594–4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Di Leo A, Jerusalem G, Petruzelka L, et al. Final overall survival: fulvestrant 500 mg vs 250 mg in the randomized CONFIRM trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106: djt337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robertson JF, Llombart-Cussac A, Rolski J, et al. Activity of fulvestrant 500 mg versus anastrozole 1 mg as first-line treatment for advanced breast cancer: results from the FIRST study. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 4530–4535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robertson JFR, Lindemann JPO, Llombart-Cussac A, et al. Fulvestrant 500 mg versus anastrozole 1mg for the first-line treatment of advanced breast cancer: follow-up analysis from the randomized FIRST study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012; 136: 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ellis MJ, Llombart-Cussac A, Feltl D, et al. Fulvestrant 500 mg versus anastrozole 1 mg for the first-line treatment of advanced breast cancer: overall survival analysis from the phase II FIRST study. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 3781–3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robertson JFR, Bondarenko IM, Trishkina E, et al. Fulvestrant 500 mg versus anastrozole 1 mg for hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer (FALCON): an international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 2997–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turner NC, Ro J, André F, et al. Palbociclib in hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cristofanilli M, Turner NC, Bondarenko I, et al. Fulvestrant plus palbociclib versus fulvestrant plus placebo for treatment of hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer that progressed on previous endocrine therapy (PALOMA-3): final analysis of the multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 425–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 4.0. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute, https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_40 (2010, accessed 10 March 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dawood S, Broglio K, Ensor J, et al. Survival differences among women with de novo stage IV and relapsed breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2010; 21: 2169–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lobbezoo DJ, van Kampen RJ, Voogd AC, et al. Prognosis of metastatic breast cancer: are there differences between patients with de novo and recurrent metastatic breast cancer? Br J Cancer 2015; 112: 1445–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cristofanilli M. Metastatic breast cancer: focus on endocrine sensitivity. Lancet 2016; 388: 2961–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mehta RS, Barlow WE, Albain KS, et al. Combination anastrozole and Fulvestrant in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Turner NC, Finn RS, Martin M, et al. Clinical considerations of the role of palbociclib in the management of advanced breast cancer patients with and without visceral metastases. Ann Oncol 2018; 29: 669–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu SG, Li H, Tang LY, et al. The effect of distant metastases sites on survival in de novo stage-IV breast cancer: A SEER database analysis. Tumour Biol 2017; 39: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graham J, Pitz M, Gordon V, et al. Clinical predictors of benefit from fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer: A Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Treat Rev 2016; 45: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roberston JFR, Di Leo A, Fazal M, et al. Fulvestrant for hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer in patients with visceral vs non-visceral metastases: findings from FALCON, FIRST, and CONFIRM [abstract]. Cancer Res 2018; 78(4 Suppl.): abstract nr PD5-09. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sutherland S, Miles D, Makris A. Use of maintenance endocrine therapy after chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2016; 69: 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kloke O, Klaassen U, Oberhoff C, et al. Maintenance treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate in patients with advanced breast cancer responding to chemotherapy: results of a randomized trial. Essen Breast Cancer Study Group. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999; 55: 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dufresne A, Pivot X, Tournigand C, et al. Maintenance hormonal treatment improves progression free survival after a first line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Int J Med Sci 2008; 5: 100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Araki K, Ishida N, Horii R, et al. Efficacy of fulvestrant 500 mg in Japanese postmenopausal advanced/recurrent breast cancer patients and factors associated with prolonged time-to-treatment failure. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015; 16: 2561–2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ishida N, Araki K, Sakai T, et al. Fulvestrant 500 mg in postmenopausal patients with metastatic breast cancer: the initial clinical experience. Breast Cancer 2016; 23: 617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kawaguchi H, Masuda N, Nakayama T, et al. Outcomes of fulvestrant therapy among Japanese women with advanced breast cancer: a retrospective multicenter cohort study (JBCRG-C06; Safari). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017; 163: 545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blancas I, Fontanillas M, Conde V, et al. Efficacy of fulvestrant in the treatment of postmenopausal women with endocrine-resistant advanced breast cancer in routine clinical practice. Clin Transl Oncol 2018; 20: 862–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heo MH, Kim HK, Lee H, et al. Clinical activity of fulvestrant in metastatic breast cancer previously treated with endocrine therapy and/or chemotherapy. Korean J Intern Med 2018; 16: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moscetti L, Fabbri MA, Natoli C, et al. Fulvestrant 500 milligrams as endocrine therapy for endocrine sensitive advanced breast cancer patients in the real world: the Ful500 prospective observational trial. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 54528–54536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pizzuti L, Natoli C, Gamucci T, et al. Anthropometric, clinical and molecular determinants of treatment outcomes in postmenopausal, hormone receptor positive metastatic breast cancer patients treated with fulvestrant: Results from a real word setting. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 69025–69037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bonotto M, Gerratana L, Di Maio M, et al. Chemotherapy versus endocrine therapy as first-line treatment in patients with luminal-like HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: a propensity score analysis. Breast 2017; 31: 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Angus L, Beije N, Jager A, et al. ESR1 mutations: moving towards guiding treatment decision-making in metastatic breast cancer patients. Cancer Treat Rev 2017; 52: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rocca A, Schirone A, Maltoni R, et al. Progress with palbociclib in breast cancer: latest evidence and clinica considerations. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2017; 9: 83–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Malorni L, Curigliano G, Minisini AM, et al. Palbociclib as single agent or in combination with the endocrine therapy received before disease progression for estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: TREnd trial. Ann Oncol 2018; 29: 1748–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]