Abstract

The Annual Review of Competence Progression is used to determine whether trainee doctors in the United Kingdom are safe and competent to progress to the next training stage.

In this article we provide evidence to inform recommendations to enhance the validity of the summative and formative elements of the Annual Review of Competency Progression. The work was commissioned as part of a Health Education England review.

We systematic searched the peer reviewed and grey literature, synthesising findings with information from national, local and specialty-specific Annual Review of Competence Progression guidance, critically evaluating the findings in the context of literature on assessing competence in medical education.

National guidance lacked detail resulting in variability across locations and specialties, threatening validity and reliability. Trainees and trainers were concerned that the Annual Review of Competence Progression only reliably identifies the most poorly performing trainees. Feedback is not routinely provided, which can leave those with performance difficulties unsupported and high performers demotivated. Variability in the provision and quality of feedback can negatively affect learning.

The Annual Review of Competence Progression functions as a high-stakes assessment, likely to have a significant impact on patient care. It should be subject to the same rigorous evaluation as other high-stakes assessments; there should be consistency in procedures across locations, specialties and grades; and all trainees should receive high-quality feedback.

Keywords: Assessment, competence, summative, formative, ARCP

Introduction

The Annual Review of Competence Progression is a yearly review of United Kingdom trainee doctors’ performance against curricular milestones.1 The Annual Review of Competence Progression is a competency-based review of whether a trainee doctor is suitable to progress to the next stage of, or to complete, their training. It aims to protect patients and the public by determining whether a trainee is safe to practice, thereby providing the mechanism by which trainees revalidate with the General Medical Council and maintain their license to practise.1 Thus, it is a high-stakes assessment for trainees, as an unsatisfactory Annual Review of Competence Progression can result in trainees undertaking more training, having their training time extended or being released from their training programme.1

Definitions and terms of reference

In this paper, we regard the Annual Review of Competence Progression process as including the systems and practices of collecting and presenting evidence about trainees’ progress during their training and the judgments made about that evidence by a panel of assessors (summative elements), and any feedback given to trainees before and after the panel (formative elements). Aspects of the Annual Review of Competence Progression, notably e-portfolios and workplace-based assessments, have been much researched,2–7 as has the competency-based model of medical training from which the Annual Review of Competence Progression arises.8–12 We did not set out to conduct a review of each of these constituent elements; rather, the main focus of this review is the Annual Review of Competence Progression itself. In doing so, our aim was to draw together evidence about the process and outputs in a manner that has not yet been done, despite the important role that the Annual Review of Competence Progression plays in trainee progression.

Rationale for the research

Dissatisfaction with the Annual Review of Competence Progression has been recorded in the literature (e.g. Viney et al.13), reflecting widespread unhappiness with the process that led to a review being undertaken by Health Education England in 2017.14 This article is drawn from the research underpinning that review, which was commissioned by Health Education England in order to support evidence-based recommendations for improving the validity of the summative and formative elements of the Annual Review of Competence Progression.15 Thus, we present a critical review of the validity of the summative and formative elements of the Annual Review of Competence Progression obtained by synthesising information from the Annual Review of Competence Progression literature, from policy and guidance documents and from the wider literature on assessing competence in medical education.

Methods

We performed a systematic search of Medline and PubMed databases using the search terms ‘ARCP’, ‘Annual Review of Competence Progression’ and ‘Annual Review of Competency Progression’ from January 2005 to August 2017. Backwards and forwards citation searches of relevant articles were conducted. As the Annual Review of Competence Progression’s implementation is guided by policy documents unlikely to be retrieved through database searches, we also conducted targeted searches of key policy-makers’ websites, including Health Education England, the General Medical Council and the United Kingdom Foundation Programme, for relevant reports and policy documents. The inclusion criteria were: articles or reports containing qualitative or quantitative information about Annual Review of Competence Progression process or outcomes; and articles published in English. Articles or reports mentioning the Annual Review of Competence Progression but not containing information about the Annual Review of Competence Progression process or outcomes were excluded.

In analysing the literature, we took validity to mean the purpose of the Annual Review of Competence Progression, whether in its current form it is fit-for-purpose and the extent to which it achieves its purpose.16 We reviewed and synthesised the information obtained from the search with information obtained from official Annual Review of Competence Progression policy and guidance documents, and a sample of policy and guidance documents which adapt national policy for use in a particular location, within a particular specialty or at a particular training grade. We critically reviewed the information obtained about the Annual Review of Competence Progression in light of evidence from the wider literature on assessing competence in medical education.

Results

Systematic search results

Searches of databases and journals plus backward- and forward-citation searching gave 297 hits in addition to 11 potentially relevant reports of which we were already aware as researchers in this field. After de-duplication, irrelevant reports were removed by screening titles and abstracts, and then by reading full-texts. This resulted in 30 reports for inclusion in the review, 17 of which were peer-reviewed. Included reports mostly related to summative aspects of the Annual Review of Competence Progression. See Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1 for details.

Policy information and guidance

We extracted policy information about the stated purposes of the Annual Review of Competence Progression and practical guidance on undertaking Annual Review of Competence Progressions from the official national guidance.1,17–20 We also reviewed a convenience sample of local and specialty-specific Annual Review of Competence Progression guidance obtained via online searches (see Supplementary Table 1).

Summative aspects of the Annual Review of Competence Progression

Criteria and evidence used by panels to make decisions

The national Annual Review of Competence Progression guidance lacks detailed information about which evidence should be assessed and how different types of evidence should be weighted. Qualitative research suggests this lack of clarity and the subsequent variability of evidence required by panels can undermine panels’ ability to make valid, reliable decisions; it can also affect trainers’ ability to guide trainees effectively through a changing curriculum while remembering the different requirements for trainees at different levels.13,21,22 To address issues of this sort, additional guidance has been issued by Medical Royal Colleges, Local Education and Training Boards, Deaneries and Trusts (see Supplementary Table 1); however, trainees believe that the resulting inconsistencies in requirements between different specialties, grades and regions are unfair.13

The Gold Guide1 implies that the Educational Supervisor Report should take precedence over other evidence. The Annual Review of Competence Progression literature suggests that, in practice, the Educational Supervisor Report and the number of workplace-based assessments a trainee has recorded are both important, although their relative weighting may vary.13,23–26 Different aspects of the same type of evidence may also be weighted differently – for example, two studies in General Practice suggested panels value the quality of individual workplace based assessments over the quantity recorded,27,28 whereas a small study of paediatric trainees found panels were satisfied when trainees achieved sufficient numbers of assessments and did not penalise trainees whose workplace based assessments contained poor quality reflections.29

There is evidence from the medical education literature that to make valid judgements, panels should consider a range of evidence reflecting different aspects of performance rated by a variety of assessors;30 both the number of assessments and the performance of the trainee are important.9 The literature is unclear about how any weighting should be applied; however, greater consistency between Annual Review of Competence Progression panels would provide equitability for trainees in different specialties.

Attendance of the supervisor and the trainee at the Annual Review of Competence Progression panel

The Gold Guide1 and the Guide to the Foundation Annual Review of Competence Progression17 take slightly different positions on the presence of the Educational Supervisor at panel meetings. The Gold Guide states the Educational Supervisor should remove themselves if it is anticipated that their trainee will get an unsatisfactory outcome (implying they can be present otherwise), whereas the Foundation Programme guidance states the Educational Supervisor should not take part in their trainee’s panel at all.

Attendance at the panel can present challenges for the Educational Supervisor: a supervisor in Rothwell’s study described it could cause problems for their educational relationship with the trainee, particularly if the Annual Review of Competence Progression outcome is negative;21 however, another study found trainers perceived this as more problematic than trainees did.31 This issue is much discussed by van der Vleuten and colleagues.11,30,32,33 While they believe supervisor input is important to increase the accuracy of panel judgements,33 they are concerned that the crucial trainee–supervisor relationship may be compromised when the supervisor makes high-stakes decisions about trainee progression. In this regard, the Foundation Programme Guidance is better aligned than the Gold Guide with the views of leading medical education researchers.

The Gold Guide and Foundation guidance state trainees may be present at Annual Review of Competence Progression panels and, in some circumstances, may even be expected to attend, such as when receiving notification of an unsatisfactory outcome. The guidance is clear, however, that a trainee’s attendance should not contribute to panel decision-making; however, the literature confirms that when trainees do attend panels, they can feel that their attendance affects the outcome they receive.13,21,25

Identifying poor performance and patient safety issues

The validity of the Annual Review of Competence Progression as a summative assessment hinges on its ability to reliably distinguish between satisfactory and unsatisfactory performance, between different levels of unsatisfactory performance and to identify patient safety issues.

The Annual Review of Competence Progression literature shows trainees and supervisors have concerns that the Annual Review of Competence Progression measures clerical rather than clinical ability; that it does not reliably identify anything other than extremely poor performance and that it cannot reliably identify patient safety concerns.13,21 We found no quantitative studies linking Annual Review of Competence Progression outcomes with patient safety or fitness to practise outcomes. Six studies found Annual Review of Competence Progression outcomes are correlated with performance in other assessments,27,34–38 which suggests it can distinguish between different levels of performance, although there is not currently sufficient data to know how sensitive it is. A recent review of workplace based assessments reached a similar conclusion2; however, a number of studies have found a link between examination performance and sanctions34,35,39 so it should be possible to establish whether Annual Review of Competence Progression outcomes also predict patient safety risks or other professional difficulties, particularly if the quality of Annual Review of Competence Progression data collection were to be improved.38

The Gold Guide states panels will require additional information about trainees anticipated to receive a poor outcome. This may enhance the accuracy of borderline judgements; however, the system relies on concerns being easy to detect, raise and investigate, and the ‘failure to fail’ phenomenon suggests trainers may be unwilling to identify trainees who are struggling.21,40 The new Generic Professional Capabilities Implementation Guidance,41 jointly produced by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the General Medical Council, goes some way to recognise and address the ‘failure to fail’ problem, stating supervisors should be given ‘time, training and support and be empowered to act if trainees are judged not to be making satisfactory progress’ (p. 13). A recent review on ‘failure to fail’40 supports training to overcome the problem and also emphasises the need for ‘strong assessment systems with established criteria’ (p. 1097) and ‘opportunities for trainees after failing’ (p. 1098). Reducing the weighting of the Educational Supervisor report in panel decision-making may also help,40 and it may be helpful to formally review trainees’ progress well before the Annual Review of Competence Progression, when the stakes are lower. This might take the form of an interim or pre-Annual Review of Competence Progression panel, which is considered in the formative section below.

Reliability of the Annual Review of Competence Progression

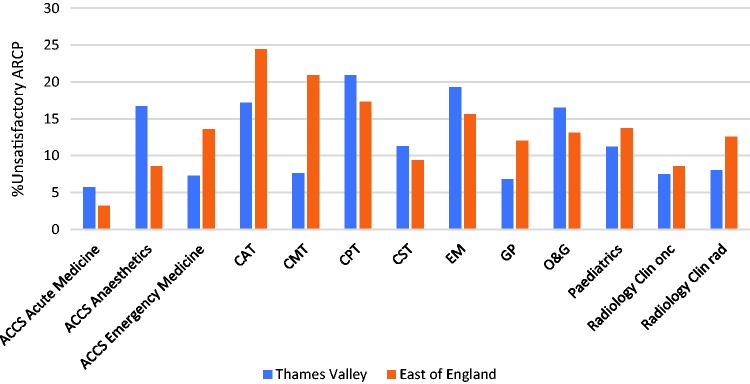

We found no published numeric estimates of the reliability of Annual Review of Competence Progression outcomes or about the number and success rates of appeals. Our own descriptive analysis of Annual Review of Competence Progression outcome data published by the General Medical Council showed that the proportion of unsatisfactory Annual Review of Competence Progression outcomes varies by specialty and region (Figure 1), reflecting qualitative reports from trainees that the requirements of Annual Review of Competence Progression panels vary ‘across specialties, regions and training grades’ (p. 113).13 Without a large-scale, longitudinal multilevel analysis, it is not clear how much these differences are due to variability in factors such as trainee ability, curricular requirements or panel decision-making approaches.

Figure 1.

Variability in the percentage of ‘unsatisfactory’ ARCP outcomes awarded to trainees from 2010 to 2016 across 13 specialties in two Health Education England Local Education and Training Boards: Thames Valley and East of England.

ACCS: acute care common stem; CAT: core anaesthetics training; CMT: core medical training; CPT: core psychiatry training; CST: core surgical training; EM: emergency medicine; GP: general practice; O&G: obstetrics & gynaecology; Clin onc: clinical oncology; Clin rad: clinical radiology. Data from http://www.gmc-uk.org/education/14105.asp

Much of the Annual Review of Competence Progression is based around workplace based assessments, which inform the Educational Supervisor Report and are presented to the panel in the e-portfolio. workplace based assessments typically have low reliability3 but reliable judgements about a trainee’s overall competence can be made using workplace based assessments6,11 so long as there are a large number of assessments and narrative reports sampled across curriculum areas and assessors.30,42 The literature suggests, however, that workplace based assessments are not always well sampled because trainees have difficulty collecting evidence, or because the high-stakes nature of the Annual Review of Competence Progression means trainees are incentivised to select assessors or cases that show them in a positive light.13

We found no evidence regarding the reliability of Educational Supervisor Reports; however, the Annual Review of Competence Progression literature indicated that a significant number may be poor quality.24,26,43 The Gold Guide refers to Educational Supervisor Reports as ‘structured’ and provides a general overview of the information that they should contain, although a template – which may improve the report’s reliability – is not provided. A non-systematic Google search revealed several templates in existence, and these varied considerably by medical specialty and region. It seems likely, therefore, that the quality and content of Educational Supervisor Reports – and therefore of the Annual Review of Competence Progression decisions based on them – vary considerably.

The way Annual Review of Competence Progression panels make decisions as a group can also affect reliability, as shown in the wider literature.44–46 A literature review on group decision-making45 included recommendations for improving how Clinical Competency Committees (similar to Annual Review of Competence Progression panels) in the United States make decisions. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has also produced an evidence-based guidebook47 containing detailed guidance on enhancing the Clinical Competence Committees judgements. No such evidence-based guidance exists for the Annual Review of Competence Progression.

Fairness of the Annual Review of Competence Progression

The Annual Review of Competence Progression literature shows that, on average, trainees who qualified outside the United Kingdom, who are male, older or from black and minority ethnic backgrounds are more likely to have an unsatisfactory Annual Review of Competence Progression outcome.21,27,35,48 The reason for these differences may be multifactorial, although it is likely that they reflect the additional risk to achievement some groups experience during training.21,49 There is also evidence that some trainees believe Annual Review of Competence Progression panels can be biased against minority ethnic and/or pregnant trainees.13,49,50

Equality and diversity training – a requirement for all panel members – does not guarantee that panel decision-making will be fair. Indeed, Ahmed51 warns that poor quality training can conceal rather than guard against discrimination. Explicit discussion of equality and diversity during decision-making may remind assessors of their commitment to fairness as they make decisions.

Formative elements of the Annual Review of Competence Progression

Feedback given to trainees by the panel

National guidance states that trainees anticipated to receive an unsatisfactory Annual Review of Competence Progression outcome are required to attend the panel to discuss previous performance and plans to improve future performance (‘feedforward’52), and that such discussions should be separate from panel decision-making. The Foundation Programme Guidance also states that trainees with an unanticipated unsatisfactory outcome should have a feedforward meeting that all trainees should have feedback about ‘targeted learning, areas for improvement and/or areas of demonstrated excellence’ (p. 18)17 and the implication is for written feedback.

We found no estimate of what proportion of trainees attend a meeting with the panel, although the literature suggests that only some do.13,53 For trainees who do attend, the research suggests that the separation of the Annual Review of Competence Progression decision-making process from feedback/feedforward may not always be clear.29,54 Where feedback is provided, trainees can perceive it as unhelpful, negative or even confrontational.13,24,55,56 Many trainees are also critical that the Annual Review of Competence Progression does not provide enough good quality feedback.21,26,52

The wider literature is clear that the benefits of feedback depend on the nature of the feedback, who it is delivered by, and how and when it is delivered.57 The provision of constructive feedback and goals for improvement by Annual Review of Competence Progression panels is likely to encourage a culture of learning and development in which trainees aspire to excellence, and may therefore enhance patient safety. In the United States, all trainees (residents/fellows) are required to receive feedback after the Clinical Competency Committee; guidance is issued on how feedback can be collated and delivered usefully.47

In terms of trainees who are released from training following an Annual Review of Competence Progression, the Gold Guide does not mandate support, stating only they ‘may wish to seek further advice […] about future career options’ (p. 56).1 By definition those required to leave training are likely to have performed very poorly. It makes sense educationally and for patient safety that ways be found to support them to develop their careers.

Preparing trainees for the Annual Review of Competence Progression

The literature suggests that when the Annual Review of Competence Progression was first introduced, many trainees did not feel prepared;25,29 it is not clear from the literature whether things have changed. Three studies reported on tools to support preparation by tracking achievement of competencies mapped to curricular requirements throughout the year.22,58,59 We also found an article describing how life coaching to address affective and attitudinal problems (rather than knowledge and skills problems) might help trainees with persistently poor Annual Review of Competence Progression performance.60

We found examples of several Local Education and Training Boards who have introduced interim reviews, designed to support trainees in preparing for the Annual Review of Competence Progression. We found no formal evaluations of interim reviews, although one study reported trainee and trainer experiences of attending a pilot Annual Planning Meeting three months before the Annual Review of Competence Progression, at which feedforward was provided.53 Trainees in the pilot found the Annual Planning Meeting encouraging, non-confrontational and supportive, and liked that it did not rely on paperwork. Interestingly, trainers felt that only trainees in difficulty should have the meetings, but trainees who were progressing satisfactorily felt they gained from it, which supports the value of constructive, stretching feedback for all.

Impact on trainee motivation

The Annual Review of Competence Progression literature shows that many trainees find the minimal competence aspect of the Annual Review of Competence Progression demotivating and discouraging of excellence.13,24–26 The existence of several different categories of unsatisfactory Annual Review of Competence Progression outcomes (cf. a single ‘satisfactory’ category), and the manner in which these categories have been used, has contributed to a perception of the Annual Review of Competence Progression as negative, bureaucratic and detrimental to learning.13,21,26

There is much discussion in the medical education literature about minimal competence8–10,12,61,62 and we cannot review it all here; however, Eva and colleagues63 argue compellingly that the concept is underpinned by the incorrect assumptions that a trainee who can perform a task well in one context can perform it equally well in all contexts, and that once competence at a task has been achieved and ‘ticked off’, a trainee no longer needs to work on it. This encourages trainees to learn just enough to achieve ‘sign-off’ and not to revisit a competence once it has been recorded as complete, which can hinder learning, result in poor performance and endanger patients. Educators can also find it difficult to help just-passing trainees since they are rated as equivalent to trainees performing at an extremely high level.

Discussion

Summary of findings

We found relatively little published research assessing the validity of the Annual Review of Competence Progression. National Annual Review of Competence Progression guidance lacks detail, resulting in variable practice across locations and specialties, and threatening the validity and reliability of outcomes. Trainees and trainers have concerns that Annual Review of Competence Progressions only identify very poorly performing trainees, which may arise partly from the ‘failure to fail’ phenomenon. The fact that feedback is not routinely provided to all trainees may leave those with specific or less serious performance issues unsupported and demotivate high performers. Variability in the provision and quality of feedback from Annual Review of Competence Progression panels and when helping trainees to prepare for panels can negatively affect learning.

Strengths and limitations of the study

To our knowledge this is the first review of the Annual Review of Competence Progression, which is a fundamental aspect of postgraduate medical training in the United Kingdom, and has parallels in postgraduate medical training globally. Our study is strengthened by the systematic and inclusive search of the peer-reviewed and grey literature on Annual Review of Competence Progressions, by including information from national and local policy documents and by comparing with the wider medical education literature on assessing competence. It was not possible to include all of the wider medical education literature on assessing competence; however, we referenced reviews and highly cited papers where possible.

Implications for policy and practice

We have highlighted that increasing the standardisation of how Annual Review of Competence Progression decisions are made, how feedback is provided and how trainees are prepared for the Annual Review of Competence Progression are crucial to combat threats to the reliability of the Annual Review of Competence Progression. While national guidance cannot provide detailed information about specific curricular requirements, it could include information on: how panels should weight different pieces of information (which would need to be supported by further research); the expectation that assessments submitted in the portfolio are sampled across the curriculum and assessors; the need for the Educational Supervisor to be absent when panels are making decisions; the need to ensure trainee presence at a panel does not influence decision-making; and evidence-based ways to guard against bias arising from panel group decision-making. In addition, the quality of locally generated tools for supporting decisions can be compared and standardised nationally.

Research is urgently needed to assess the predictive validity of the Annual Review of Competence Progression, in particular its ability to distinguish reliably between satisfactory and unsatisfactory performance and progress, to distinguish between the different levels of unsatisfactory performance and to identify patient safety issues. This will require the collection and provision of good quality data to researchers and the publication of findings. Initiatives such as the United Kingdom Medical Education Database64 provide a mechanism for linking Annual Review of Competence Progression data with other outcomes and providing linked data to researchers, although the quality of such research will depend on the quality of the Annual Review of Competence Progression data. Fairness should also be considered as part of research into the validity of the Annual Review of Competence Progression, as is the case for other high-stakes assessments.65,66 As Tiffin and colleagues35 point out, it is unlikely that the Annual Review of Competence Progression is ‘free from cultural influences and opportunities for assessor bias’.

The wider educational evidence suggests that ensuring all trainees receive constructive feedback to improve their learning and performance, including ‘stretching’ feedback for those performing well, will increase the educational value of the Annual Review of Competence Progression process and help motivate high performers. Providing all trainees with a pre-Annual Review of Competence Progression meeting with their Educational Supervisor and another person, possibly an Annual Review of Competence Progression panel member, to check progress and provide feedback can help ensure any problems are addressed early and will guard against ‘failure to fail’ by reducing the high-stakes nature of the final Annual Review of Competence Progression.

Conclusions

Assessment of trainees is necessary to ensure standards and protect patients. Epstein and Hundert62 state that assessment is ‘a statement of institutional values’ (p. 231), and thus investment in developing the Annual Review of Competence Progression to the highest educational standards demonstrates the value placed on developing excellent doctors, and will help combat the current impression of the Annual Review of Competence Progression as a relatively ineffective, bureaucratic, box-ticking process. We suggest that investment in undertaking high-quality and continual evaluation of the Annual Review of Competence Progression is essential to ensure the validity, reliability, robustness and defensibility of the Annual Review of Competence Progression and its role in postgraduate training.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Assessing professional competence: a critical review of the Annual Review of Competence Progression by Katherine Woolf, Michael Page and Rowena Viney in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Declarations

Competing Interests

Katherine Woolf is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Career Development Fellowship (Grant Reference Number CDF-2017-10-008). The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Funding

This research was funded by Health Education England.

Ethics approval

This was a review of the literature and no ethical approval was required.

Guarantor

KW

Contributorship

KW designed the study and conducted the literature review using search parameters and inclusion and exclusion criteria agreed by KW and MP in advance. KW analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the original research report. MP redrafted the research report in collaboration with KW and RV. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Gloria Wong, a UCL medical student, for helping with the search for guidance documents. Thank you also to Catherine O’Keeffe for comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by David Parry.

References

- 1.A Reference Guide for Postgraduate Specialty Training in the UK: The Gold Guide. 6th Edition ed.: Conference of Postgraduate Medical Deans of the United Kingdom, 2016.

- 2.Barrett A, Galvin R, Steinert Y, et al. A BEME (Best Evidence in Medical Education) systematic review of the use of workplace-based assessment in identifying and remediating poor performance among postgraduate medical trainees. Syst Rev 2015; 4: 65–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kogan JR, Holmboe ES, Hauer KE. Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: a systematic review. JAMA 2009; 302: 1316–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massie J, Ali JM. Workplace-based assessment: a review of user perceptions and strategies to address the identified shortcomings. Adv Health Sci Educ 2016; 21: 455–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller A, Archer J. Impact of workplace based assessment on doctors’ education and performance: a systematic review. BMJ 2010; 341: c5064–c5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moonen-van Loon JMW, Overeem K, Donkers HHLM, van der Vleuten CP, Driessen EW. Composite reliability of a workplace-based assessment toolbox for postgraduate medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ 2013; 18: 1087–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driessen E, Van Tartwijk J, Van Der Vleuten C, et al. Portfolios in medical education: why do they meet with mixed success? A systematic review. Med Educ 2007; 41: 1224–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, et al. The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach 2010; 32: 676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ten Cate O. The false dichotomy of quality and quantity in the discourse around assessment in competency-based education. Adv Health Sci Educ 2015; 20: 835–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT. Assessing professional competence: from methods to programmes. Med Educ 2005; 39: 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT, Scheele F, et al. The assessment of professional competence: building blocks for theory development. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2010; 24: 703–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach 2010; 32: 638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viney R, Rich A, Needleman S, et al. The validity of the Annual Review of Competence Progression: a qualitative interview study of the perceptions of junior doctors and their trainers. J R Soc Med 2017; 110: 110–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HEE to lead review to increase support for junior doctors career progression. See https://hee.nhs.uk/news-blogs-events/news/hee-lead-review-increase-support-junior-doctors-career-progression (2016, last checked 21 June 2018).

- 15.Woolf K and Page M. Academic support for the Assessment and Appraisal Workstream of Health Education England’s review of the ARCP. 2017. University College London.

- 16.Stobart G. Validity in formative assessment. In: Gardner J. (ed). Assessment and Learning, 2nd ed London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guide to the Foundation Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP) Process – 2017. 2017. Foundation Programme.

- 18.The Foundation Programme Reference Guide. 2016. Foundation Programme.

- 19.The GMC protocol for making revalidation recommendations: Guidance for Responsible Officers and Suitable Persons. Manchester: General Medical Council, 2015.

- 20.COPMeD guidance on making revalidation recommendations for doctors in postgraduate training. 2017. Conference of Postgraduate Medical Deans of the United Kingdom.

- 21.Rothwell C. A study to identify the factors that either facilitate or hinder medical specialty trainees in their Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP), with a focus on adverse ARCP outcomes. PhD Thesis, Durham University, 2017.

- 22.Ntatsaki E, Tugnet N, Nadesalingam K, et al. The pre-Annual Review of Competence Progression checklist: demystefying the annual review of competence preparation for rheumatology. Rheumatology 2015; 54: 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKee RF. The intercollegiate surgical curriculum programme (ISCP). Surgery 2008; 26: 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eynon-Lewis A, Price M. Reviewing the ARCP process: experiences of users in one English deanery. BMJ 2012; 345: e4978–e4978. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peiris L, Cresswell B. How to succeed in the Annual Reviews of Competency Progression (ARCP). Surgery 2012; 30: 455–458. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dormandy L, Laycock K. Triumph of process over practice: changes to assessment of physicians. BMJ 2015; 351: h3810–h3810. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bedward J, Davison I, Burke S, et al. Evaluation of the RCGP GP Training Curriculum. 2011. University of Birmingham, University of Warwick.

- 28.Bodgener S, Denney M, Howard J. Consistency and reliability of judgements by assessors of case based discussions in general practice specialty training programmes in the United Kingdom. Educ for Primary Care 2017; 28: 45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodyear H, Wall D, Bindal T. Annual review of competence: trainees' perspective. Clin Teach 2013; 10: 394–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Vleuten CPM. A programmatic approach to assessment. Med Sci Educ 2016; 26: 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho SP, Parry D, Wade W. Lessons learnt from a pilot of assessment for learning. Clin Med 2014; 14: 577–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT, Driessen EW, et al. A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Med Teach 2012; 34: 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT, Driessen EW, et al. Twelve tips for programmatic assessment. Med Teach 2015; 37: 641–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludka-Stempien K. Predictive validity of the examination for the Membership of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom. University College London, London, 2015.

- 35.Tiffin PA, Illing J, Kasim AS, et al. Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP) performance of doctors who passed Professional and Linguistic Assessments Board (PLAB) tests compared with UK medical graduates: national data linkage study. BMJ 2014; 348: g2622–g2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gale TCE, Roberts MJ, Sice PJ, et al. Predictive validity of a selection centre testing non-technical skills for recruitment to training in anaesthesia. BJA 2010; 105: 603–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pashayan N, Gray S, Duff C, et al. Evaluation of recruitment and selection for specialty training in public health: interim results of a prospective cohort study to measure the predictive validity of the selection process. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016; 38: e194–e200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davison I, McManus I and Taylor C. Evaluation of GP Specialty Selection. 2016. University of Birmingham, University College London, University of Warwick.

- 39.Wakeford R, Ludka K, Woolf K, McManus IC. Fitness to practise sanctions in UK doctors are predicted by poor performance at MRCGP and MRCP(UK) assessments: data linkage study. BMC Medicine 2018; 16: 230. 10.1186/s12916-018-1214-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Yepes-Rios M, Dudek N, Duboyce R, et al. The failure to fail underperforming trainees in health professions education: a BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 42. Med Teach 2016; 38: 1092–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Generic professional capabilities: guidance on implementation for colleges and faculties. 2017. Manchester: Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the General Medical Council.

- 42.Driessen E, Scheele F. What is wrong with assessment in postgraduate training? Lessons from clinical practice and educational research. Med Teach 2013; 35: 569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards J, Petra H. The effects of external quality management on workplace-based assessment. Educ Prim Care 2013; 24: 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hauer KE, Chesluk B, Iobst W, et al. Reviewing residents’ competence: a qualitative study of the role of clinical competency committees in performance assessment. Acad Med 2015; 90: 1084–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hauer KE, ten Cate O, Boscardin CK, et al. Ensuring resident competence: a narrative review of the literature on group decision making to inform the work of clinical competency committees. J Grad Med Educ 2016; 8: 8–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chahine S, Cristancho S, Padgett J, et al. How do small groups make decisions? Perspect Med Educ 2017; 6: 192–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andolsek K, Padmore J, Hauser KE, et al. Clinical Competency Committees A Guidebook for Programs. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), 2015.

- 48.Pyne Y, Ben-Shlomo Y. Older doctors and progression through specialty training in the UK: a cohort analysis of General Medical Council data. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e005658–e005658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woolf K, Rich A, Viney R, et al. Perceived causes of differential attainment in UK postgraduate medical training: a national qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e013429–e013429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rich A, Viney R, Needleman S, et al. ‘You can't be a person and a doctor’: the work–life balance of doctors in training—a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e013897–e013897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmed S. ‘You end up doing the document rather than doing the doing’: diversity, race equality and the politics of documentation. Ethn Racial Stud 2007; 30: 590–609. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rees CE, Cleland JA, Dennis A, et al. Supervised learning events in the foundation programme: a UK-wide narrative interview study. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e005980–e005980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bindal T, Wall D, Goodyear H. Annual planning meetings: views and perceptions. Clin Teach 2014; 11: 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vance G, Williamson A, Frearson R, et al. Evaluation of an established learning portfolio. Clin Teach 2013; 10: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vasudev A, Vasudev K, Thakkar P. Trainees' perception of the Annual Review Of Competence Progression: 2-year survey. Psychiatrist 2010; 34: 396–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vasudev A, Thakkar P, KV The 1st Annual Review of Competence Progression, a new way of assessing trainee doctors: trainees’ perception. Med Teach 2010; 32: 94–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brennan N, Bryce M, Pearson M, et al. Towards an understanding of how appraisal of doctors produces its effects: a realist review. Med Educ 2017; 51: 1002–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ap Dafydd D, Williamson R, Blunt P, et al. Development of training-related health care software by a team of clinical educators: their experience, from conception to piloting. Adv Med Educ Pract 2016; 7: 635–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wentworth L, Wardle K, Ruddlesdin J, et al. Members’ presentations abstract: competency mapping in quality management of geriatric medicine training – a survey of trainees in the North-Western Deanery. Med Educ 2011; 45: 1–85.21528500 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gale AC, Gilbert J, Watson A. Life coaching to manage trainee underperformance. Med Educ 2014; 48: 539–539– 539–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bok HG, Teunissen PW, Favier RP, et al. Programmatic assessment of competency-based workplace learning: when theory meets practice. BMC Med Educ 2013; 13: 123–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA 2002; 287: 226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eva KW, Bordage G, Campbell C, et al. Towards a program of assessment for health professionals: from training into practice. Adv Health Sci Educ 2016; 21: 897–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dowell J, Cleland J, Fitzpatrick S, et al. The UK medical education database (UKMED) what is it? Why and how might you use it? BMC Med Educ 2018; 18: 6–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Denney ML, Freeman A, Wakeford R. MRCGP CSA: are the examiners biased, favouring their own by sex, ethnicity, and degree source? Br J Gen Pract 2013; 63: e718–e725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McManus IC, Elder AT, Dacre J. Investigating possible ethnicity and sex bias in clinical examiners: an analysis of data from the MRCP(UK) PACES and nPACES examinations. BMC Med Educ 2013; 13: 103–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Assessing professional competence: a critical review of the Annual Review of Competence Progression by Katherine Woolf, Michael Page and Rowena Viney in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine