Abstract

Background

Fibromyalgia syndrome displays sympathetically maintained pain features such as frequent post-traumatic onset and stimuli-independent pain accompanied by allodynia and paresthesias. Heart rate variability studies showed that fibromyalgia patients have changes consistent with ongoing sympathetic hyperactivity. Norepinephrine-evoked pain test is used to assess sympathetically maintained pain syndromes. Our objective was to define if fibromyalgia patients have norepinephrine-evoked pain.

Methods

Prospective double blind controlled study. Participants: Twenty FM patients, and two age/sex matched control groups; 20 rheumatoid arthritis patients and 20 healthy controls. Ten micrograms of norepinephrine diluted in 0.1 ml of saline solution were injected in a forearm. The contrasting substance, 0.1 ml of saline solution alone, was injected in the opposite forearm. Maximum local pain elicited during the 5 minutes post-injection was graded on a visual analog scale (VAS). Norepinephrine-evoked pain was diagnosed when norepinephrine injection induced greater pain than placebo injection. Intensity of norepinephrine-evoked pain was calculated as the difference between norepinephrine minus placebo-induced VAS scores.

Results

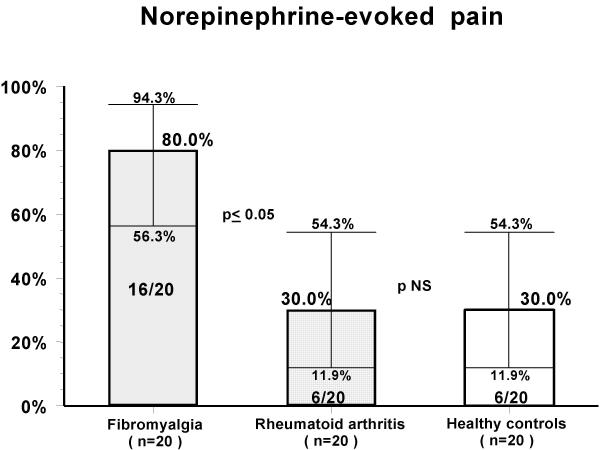

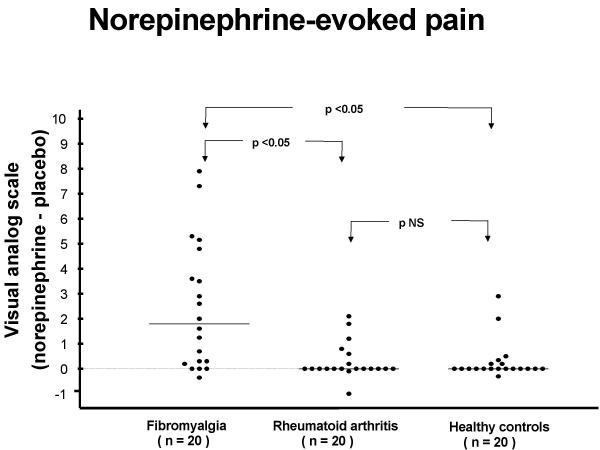

Norepinephrine-evoked pain was seen in 80 % of FM patients (95% confidence intervals 56.3 – 94.3%), in 30 % of rheumatoid arthritis patients and in 30 % of healthy controls (95% confidence intervals 11.9 – 54.3) (p < 0.05). Intensity of norepinephrine-evoked pain was greater in FM patients (mean ± SD 2.5 ± 2.5) when compared to rheumatoid arthritis patients (0.3 ± 0.7), and healthy controls (0.3 ± 0.8) p < 0.0001.

Conclusions

Fibromyalgia patients have norepinephrine-evoked pain. This finding supports the hypothesis that fibromyalgia may be a sympathetically maintained pain syndrome.

Background

Several groups of investigators, using heart rate variability analysis have shown that fibromyalgia (FM) patients have changes consistent with persistent sympathetic hyperactivity and concurrent hypo-reactivity to orthostatic stress [1-6]. This body of evidence led to the proposal that FM may be a sympathetically maintained pain syndrome [7]. This pathogenesis would explain the peculiar pain syndrome that FM patients display, as well as the remaining manifestations that this illness exhibits in different organs and systems of the body [8].

Norepinephrine (NE)-evoked pain is the most widely used clinical research test to define sympathetically maintained pain syndromes. Several studies have shown that different types of neuropathic pain previously submissive to sympatholytic therapy are rekindled by cutaneous application of NE. Ali et al described 12 patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy (complex regional pain syndrome type I) in whom NE application rekindled pain [9]. Torebjork et al. described that NE application can aggravate the pain in some, but not all sympathetically maintained pain patients [10]. Davis et al reported that the alpha 2-adrenergic agonist clonidine, delivered by transdermal patches relieves hyperalgesia in sympathetically maintained pain [11]. Clonidine activates pre-synaptic adrenergic autoreceptors resulting in a reduction of norepinephrine release. This effectively decreases activation of the post-synaptic alpha 1 receptors.

Methods

Participants

We studied 20 patients with FM and two age (+/- 5 years) and sex matched control groups, namely: 20 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and 20 apparently healthy persons. The eligibility criteria for the 3 different groups were as follows: for FM patients, to fulfill the 1990 ACR classification criteria for this syndrome [12] and absence of comorbidity. For RA; to fulfill the corresponding classification criteria [13] and to have an active disease. An exclusion clause for both control groups was the presence of widespread pain and/or more than 11 FM tender points.

Analgesic/anti-inflammatory medications were not allowed in the immediate 24 hr. before the study. All subjects signed an informed consent form. The Human Research Committee of our Institute approved the protocol.

Interventions

The day of the study, subjects filled out a 10 cm visual analog scale for pain, fatigue, sleep difficulties, morning stiffness and disability, as well as a structured questionnaire about the presence of the distinctive features of FM according to the ACR criteria [12] and of chronic fatigue syndrome according to the International Study Group criteria. [14]. Norepinephrine (NE) was administered under a double blind protocol. Using insulin syringes with 29 gauge needles, 10 micrograms of NE diluted in 0.1 ml of normal saline solution or 0.1 ml of normal saline solution alone were injected subcutaneously in the volar aspect of a forearm. The contrasting substance was injected in the opposite forearm.

Objective

To define if subcutaneous injections of NE induces pain in FM patients.

Outcome measures

Subjects graded on a 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS), the maximum local pain elicited during the 5 minutes post-injection. NE-evoked pain was diagnosed when NE injection induced greater pain than placebo injection. Intensity of NE-evoked pain was calculated as the difference between the VAS score in the NE-injected forearm minus VAS score in the placebo-injected forearm.

Associated adverse events were recorded.

Sample size

It was arbitrarily set at 20 participants per group. This is a pilot study, we had no pre-trial information on the expected response to NE for RA patients and FM patients.

Randomization, sequence generation

A coin flip was used to allocate the intervention sequence placebo-NE for each participant. Left forearms were injected first.

Allocation concealment and blinding

The physician who performed the injections was blinded as to the substance she was administering, she was not blinded as to patient's diagnosis. Injected substance identity was concealed until after outcomes were measured.

Statistical methods

Mean and standard deviation are used for descriptive values. Binomial distributed values are calculated as proportion with its 95% confidence intervals. Chi square analysis is used to compare qualitative variables. One-way analysis of variance to compare continuous variables. Bonferroni's multiple comparison test to define inter-group differences. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Baseline data

It is outlined in table 1. Ninety percent of FM patients were female. Their mean age was 43 years.

Table 1.

Baseline Data of Fibromyalgia Patients and Two Age/Sex Matched Control Groups

| Fibromyalgia | Rheumatoid arthritis | Healthy controls | |

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 43.0 ± 15.2 | 45.4 ± 13.1 | 42.1 ± 14.8 |

| Gender (F/M) | (18/2) | (18/2) | (18/2) |

| Total fibromyalgia points, (mean ± SD) | 16.8 ± 1.9* | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.7 ± 1.5 |

| VAS score, (mean ± SD) | |||

| Pain | 6.5 ± 2.5** | 4.3 ± 2.5 | 0 ± 0 |

| Fatigue | 7.2 ± 2.4* | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 0.5 ± 1.3 |

| Sleep disturbances | 5.9 ± 2.6* | 2.0 ± 2.5 | 0.2 ± 1.1 |

| Morning stiffness | 4.8 ± 3.7** | 2.4 ± 2.6 | 0.2 ± 0.7 |

| Disability | 7.1 ± 2.2* | 3.1 ± 3.2 | 0.2 ± 0.6 |

| Symptoms, % of patients (95% confidence interval) | |||

| Anxiety | 90 (68.3–98.8)* | 45 (23.0–68.5) | 40(19.1–63.9) |

| Headache | 90 (68.3–98.8)* | 35(15.4–59.2) | 25(8.7–49.1) |

| Weakness | 90 (68.3–98.8)* | 45 (23.0–68.5) | 10(1.2–31.7) |

| Forgetfulnes | 85(62.1–96.8)* | 50 (27.2–72.8) | 15 (3.2–37.9) |

| Paresthesias | 85(62.1–96.8)* | 35(15.4–59.2) | 30(11.9–54.3) |

| Irritable bowel | 65 (40.8–84.6)* | 10(1.2–31.7) | 20 (5.7–43.7) |

| Sicca syndrome | 53 (28.9–75.5)** | 45 (23.0–68.5) | 10(1.2–31.7) |

| Sore throat | 45 (23.0–68.5)** | 25(8.7–49.1) | 5(0.1–24.9) |

| Acute onset | 40(19.1–63.9)* | 5 (0.1–24.9) | 0(0–16.8) |

| Cold hands | 40(19.1–63.9)** | 15(3.2–37.9) | 0(0–16.8) |

| Low grade fever | 20 (5.7–43.7)** | 0(0–16.8) | 0(0–16.8) |

| Lymph gland enlargement | 5 (0.1–24.9) | 5 (0.1–24.9) | 0(0–16.8) |

| VAS = 10 cm visual analog scale | |||

| *=p < 0.05 vs both control groups | |||

| ** = p < 0.05 vs healthy controls only | |||

When compared to RA patients, FM subjects had similar VAS scores in pain perception and morning stiffness. Nevertheless they had higher scores in fatigue, sleep disturbances and disability perception.

Outcomes and estimation

Eighty percent of FM patients had NE-evoked pain according to our definition, in contrast 30% of RA patients and 30% of normal controls had such response (p < 0.05) (figure 1). Likewise NE-evoked pain intensity was greater in FM group (mean +/- SD 2.5 +/- 2.5) when compared to RA patients (0.3 +/- 0-7) and healthy controls (0.3 +/- 0.8) p < 0.0001. (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Norepinephrine-evoked pain

Figure 2.

Norepinephrine-evoked pain

Response to placebo in FM group (mean +/- SD 0.5 +/- 1.3) was not different when compared to RA group (0.1 +/- 0.2) p = 0.07.

Adverse events

Pain induction was severe in two FM patients injected with NE (figure 2). Other adverse events are outlined in table 2. Notable was a peculiar spreading of pain to other areas of the extremity seen in 8/20 of FM patients after NE injection.

Table 2.

Number of cases with adverse events after norepinephrine (NE) and placebo injections

| Fibromyalgia | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Healthy Controls | ||||

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | ||||

| placebo | NE | placebo | NE | placebo | NE | |

| Spreading of pain | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pale halo | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Paresthesias | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Palpitations | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sweating | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Distal swelling | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Discontinued medications

Table 3 shows prescribed non-steroidal analgesic/anti-inflammatory drugs and centrally acting medications with their corresponding plasma half-life. Analgesic/anti-inflammatory drugs were discontinued at least 24 hours before the study.

Table 3.

Prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and centrally acting agents. (*) means that the drug was discontinued at least 24 hrs before the study. Plasma half-life of each compound is also indicated.

| Fibromyalgia | Rheumatoid Arthritis | ||||

| Drug | Number of patients | Plasma half-life (hours) | Drug | Number of patients | Plasma half-life (hours) |

| clonazepam | 6 | 20–60 | acetaminophen* | 4 | 4–6 |

| acetaminophen* | 5 | 4–6 | celecoxib* | 3 | 10–12 |

| mianserin | 2 | 21–61 | diclofenac* | 3 | 3–7 |

| alprazolam | 2 | 12–15 | piroxicam* | 2 | 34–50 |

| bromazepam | 1 | 20 | clonazepam | 1 | 20–60 |

| triazolam | 1 | 1.5–5.5 | alprazolam | 1 | 12–15 |

| piroxicam* | 1 | 34–50 | indomethacin* | 1 | 4–5 |

| celecoxib* | 1 | 10–12 | aspirin* | 1 | 2–3 |

| ketoprofen* | 1 | 1.5–4 | rofecoxib* | 1 | 17 |

| fluoxetine | 1 | 96–144 | ibuprofen* | 1 | 2–3 |

| gabapentin* | 1 | 5–9 | gabapentin* | 1 | 5–9 |

Discussion

Interpretation

Our double blind study demonstrates that most FM patients have NE-evoked pain. This type of response was significantly different from the response observed in another chronic painful condition, rheumatoid arthritis, and also different from healthy controls. Furthermore, the intensity of NE-evoked pain was greater in FM subjects when compared to the other two control groups. These results give experimental support to the notion that FM is a sympathetically maintained pain syndrome.

Generalizability

We recognize limitations in our study; although we used a double blind protocol, nevertheless patient's diagnosis (FM, RA or healthy control) could not be blinded to the physician who performed the injections. We believe this fact did not bias the results since all participants were given the same information on what to expect from the injections. Such information was basically what was written in the consent form.

Our study did not explore the specificity of the hyperalgesic response to NE in the FM group. To test this possibility it would be necessary to first perform sympathetic blockade and latter attempt to rekindle pain with NE. Another possible approach would be an additional intervention injecting NE mixed with an adrenergic blocking agent. Nevertheless, such approach has theoretical shortcomings as some adrenergic blocking agents also have intrinsic anesthetic properties.

The 24 hours period of analgesic/anti-inflammatory drugs discontinuation may have been insufficient for the patients to be free of long acting medications effects. Likewise centrally acting drugs may have blunted the response to NE. Nevertheless we believe these circumstances did not impact the results as only 3 patients (2 with RA and 1 with FM) were taking long-acting compounds such as piroxicam (table 3). Of the ten FM patients that were on centrally acting drugs 7 had NE-evoked pain, similarly 9/10 FM subjects that were not taking such drugs had NE-evoked pain.

The injected dosages of 10 micrograms of NE were based on what was previously reported in the neuropathic pain literature and also on a pre-trial NE injections in ourselves that demonstrated no untoward effects and no pain elicitation with this dosage. Future studies may find more appropriate NE dosages as well as different routes of administration such as transdermal patches, and perhaps different dilutions to cover a wider area and thus possibly better discriminate the hyperalgesic response of patients from controls. We speculate about the possibility that once perfected, NE-evoked pain may evolve into a useful clinical test for FM.

Overall evidence

The first study of autonomic nervous system function in FM was a controlled therapeutic trial reported by Bengtsson and Bentgsson in 1988 [15]. They described that anesthetic blockade of the sympathetic stellate ganglion, markedly decreased regional pain and tender points in contrast to the lack of effect of sham placebo injection into the neck area. Subsequently Vaeroy et al. using Doppler probes showed that FM patients have diminished distal vasomotor response to acoustic or cold stimulation [16]. With the introduction in recent years of a new powerful technique, heart rate variability analysis, several groups of investigators demonstrated that FM subjects have changes consistent with relentless sympathetic hyperactivity with concurrent hypo-reactivity to stress. [1-6]. This accumulated evidence led to propose that FM may be a sympathetically maintained pain syndrome [7].

Sympathetically maintained pain is characterized by its frequent post-traumatic onset, by the presence of chronic stimuli-independent pain that is accompanied by allodynia, paresthesias and distal vasomotor changes. Typically, this type of pain is diminished by sympathetic blockade [17]. FM pain has such characteristics. It is well known that FM syndrome has frequent post-traumatic onset particularly when the trauma is directed to neck area [18], a site with unique superficial sympathetic ganglia network. Pain in FM is clearly stimuli-independent, as no underlying peripheral tissue damage has been identified. FM tender points reflect a state of generalized allodynia [19]. Paresthesias are more frequent in FM when compared to patients with other systemic rheumatic diseases [12]. In FM there are distal vasomotor changes manifested as pseudo-Raynaud phenomenon [16] and soft tissue swelling. Finally as mentioned before, FM pain appears to be submissive to sympatholytic maneuvers.

In addition to the pain syndrome, sympathetic hyperactivity may explain other typical manifestations of FM such as sleep problems, irritable bowel, sicca symptoms, and anxiety [8]. The concurrent sympathetic hyporeactivity that these patients display (probably due to a ceiling effect) provides a coherent explanation for their constant fatigue [8]

Conclusion

FM patients have NE-evoked pain. This finding supports the hypothesis that FM may be a sympathetically maintained pain syndrome.

Competing interests

None declared

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Manuel Martinez-Lavin, Email: mmlavin@infosel.net.mx.

Marcela Vidal, Email: Dr4u505@aol.com.

Rosa-Elda Barbosa, Email: rebcob@yahoo.com.

Carlos Pineda, Email: carpineda@yahoo.com.

Jose-Miguel Casanova, Email: casanova6951@terra.com.mx.

Arnulfo Nava, Email: navazava@hotmail.com.

References

- Martinez-Lavin M, Hermosillo AG, Mendoza C, Ortiz R, Cajigas JC, Pineda C, Nava A, Vallejo M. Orthostatic sympathetic derangement in subject with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:714–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Lavin M, Hermosillo AG, Rosas M, Soto ME. Circadian studies of autonomic nervous balance in patients with fibromyalgia. A heart rate variability analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1966–1971. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199811)41:11<1966::AID-ART11>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen J, Lang E, Balint G, Trocsanyi M, Muller W. Orthostatic sympathetic derangement of baroreflex in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:823–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj RR, Brouillard D, Simpsom CS, Hopman WM, Abdollah H. Dysautonomia among patients with fibromyalgia: A noninvasive assessment. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2660–2665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H, Neumann L, Shore M, Amir M, Cassuto Y, Buskila D. Autonomic dysfunction in patients with fibromyalgia: application of power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2000;29:217–227. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(00)80010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H, Neumann L, Alhosshle A, Kotler M, Abu-Shakra M, Buskila D. Abnormal sympathovagal balance in men with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:581–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Lavin M. Is fibromyalgia a generalised reflex sympathetic dystrophy?. clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Lavin M, Hermosillo AG. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction may explain the multisystem features of fibromyalgia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2000;29:197–199. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(00)80008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Z, Raja SN, Wesselmann U, Fuchs PN, Meyer RA, Campbell JN. Intradermal injection of norepinephrine evokes pain in patients with sympathetically maintained pain. Pain. 2000;88:161–68. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torebjork E, Wahren L, Wallin G, Hallin R, Koltzenburg M. Noradrenaline-evoked pain in neuralgia. Pain. 1995;63:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00140-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KD, Treede RD, Raja SN, Meyer RA, Campbell JN. Topical application of clonidine relieves hyperalgesia in patients with sympathetically maintained pain. Pain. 1991;47:309–17. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90221-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennet RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Tugwell P, Campbell SM, Abeles M, dark P, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–171. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healy LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Strauss SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson A, Bengtsson M. Regional sympathetic blockade in primary fibromyalgia. Pain. 1988;33:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaeroy H, Qiao Z, Morkrid L, Forre O. Altered sympathetic nervous system response in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:1460–1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg H, Hoffman U, Mohadjer M, Scheremet R. Sympathetic nervous system and pain: a clinical reappraisal. Behav Brain Sci. 1997;20:426–436. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X97271487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buskila D, Neumann L, Vaisberg G, Alkalay D, Wolfe F. Increased rates of fibromyalgia following cervical spine injury. A controlled study of 161 cases of traumatic injury. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:446–452. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. Advances in fibromyalgia: possible role for central neurochemicals. Am J Med Sci. 1998;315:377–384. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199806000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]