Abstract

The bile acid (BA) nuclear receptor, farnesoid X receptor (FXR/NR1H4), maintains metabolic homeostasis by transcriptional control of numerous genes, including an intestinal hormone, fibroblast growth factor-19 (FGF19; FGF15 in mice). Besides activation by BAs, the gene-regulatory function of FXR is also modulated by hormone or nutrient signaling–induced post-translational modifications. Recently, phosphorylation at Tyr-67 by the FGF15/19 signaling–activated nonreceptor tyrosine kinase Src was shown to be important for FXR function in BA homeostasis. Here, we examined the role of this FXR phosphorylation in cholesterol regulation. In both hepatic FXR-knockout and FXR-knockdown mice, reconstitution of FXR expression up-regulated cholesterol transport genes for its biliary excretion, including scavenger receptor class B member 1 (Scarb1) and ABC subfamily G member 8 (Abcg5/8), decreased hepatic and plasma cholesterol levels, and increased biliary and fecal cholesterol levels. Of note, these sterol-lowering effects were blunted by substitution of Phe for Tyr-67 in FXR. Moreover, consistent with Src's role in phosphorylating FXR, Src knockdown impaired cholesterol regulation in mice. In hypercholesterolemic apolipoprotein E–deficient mice, expression of FXR, but not Y67F-FXR, ameliorated atherosclerosis, whereas Src down-regulation exacerbated it. Feeding or treatment with an FXR agonist induced Abcg5/8 and Scarb1 expression in WT, but not FGF15-knockout, mice. Furthermore, FGF19 treatment increased occupancy of FXR at Abcg5/8 and Scarb1, expression of these genes, and cholesterol efflux from hepatocytes. These FGF19-mediated effects were blunted by the Y67F-FXR substitution or Src down-regulation or inhibition. We conclude that phosphorylation of hepatic FXR by FGF15/19-induced Src maintains cholesterol homeostasis and protects against atherosclerosis.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, cholesterol regulation, bile acid, post-translational modification (PTM), nuclear receptor, ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 5 (Abcg5), Abcg8, hypercholesterolemia, reverse cholesterol transport, scavenger receptor class B member 1 (Scarb1), biliary excretion, metabolic homeostasis, FGF15

Introduction

The bile acid (BA)5-sensing nuclear receptor, farnesoid X receptor (FXR, NR1H4), plays an important role in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis by transcriptional control of numerous genes, including a gut hormone, fibroblast growth factor-19 (human FGF19, mouse FGF15), and an orphan nuclear receptor, small heterodimer partner (SHP, NR0B2) (1–3). After a meal, FXR is activated by transiently elevated BAs, inhibits hepatic BA synthesis, and promotes biliary excretion to maintain BA homeostasis and protect the liver from bile toxicity. FXR also has many other beneficial functions, including cholesterol-lowering effects. FXR-knockout (KO) mice have increased plasma cholesterol levels and pro-atherogenic lipoprotein profiles (4–7). Conversely, treatment with FXR agonists in mice was shown to decrease sterol levels, in part, by increasing expression of hepatic genes involved in reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), including Scarb1, Abcg5, and Acg8 (8–11). RCT is an anti-atherogenic pathway, in which high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol is transported to the liver, where it can be secreted into bile as free cholesterol or converted into BAs for biliary excretion (2, 11–13). Although a role for FXR in the sterol regulation has been shown from genetic mouse and pharmacological studies, the molecular signaling mechanisms, particularly in response to nutrient and hormonal cues, have not been demonstrated.

An intestinal hormone, FGF15/19, is induced by FXR and acts at the liver to maintain metabolic homeostasis during the transition from the fed to fasted states independent of insulin action (3, 14). FGF15/19 mediates postprandial hepatic responses, which include the inhibition of BA biosynthesis, activation of glycogen and protein synthesis, and repression of hepatic autophagy and one-carbon metabolism (3, 14–16). In addition to these functions, FGF15/19 has been implicated in the regulation of cholesterol metabolism. FGF15-KO mice had elevated cholesterol levels, and treatment of mice with FGF19 led to decreased plasma sterol levels (17–19). The mechanisms by which FGF15/19 decreases cholesterol levels are unclear, although recent studies have shown that SHP mediates FGF15/19 function to inhibit hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis and intestinal cholesterol absorption (20, 21).

The transcriptional function of FXR is primarily regulated by its physiological ligands, BAs, but can also be profoundly modulated by signaling-induced post-translational modifications (PTMs), sometimes in a gene-selective manner, and dysregulated PTMs are associated with metabolic disease (22–24). For example, acetylation of FXR is normally dynamically regulated during feeding/fasting cycles via p300 acetyltransferase and SIRT1 deacetylase, but constitutively elevated in obese mice (22). The elevated FXR acetylation in obesity blocks SUMOylation of FXR, which contributes to activation of proinflammatory transcriptional responses (22, 24). Further, FXR is O-GlcNAcylated in response to high glucose levels in the fed state, leading to increased FXR stability and transcriptional function (25). Recently, phosphorylation of FXR at Tyr-67 by a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, c-Src, in response to postprandial FGF15/19 signaling was shown to be important for FXR function in BA homeostasis (26).

In this study, we examined a role of Src-mediated phosphorylation of FXR in sterol regulation in mice. Utilizing Y67-FXR mutations and Src down-regulation, we show that phosphorylation of hepatic FXR at a single residue, Tyr-67, is important for the maintenance of cholesterol homeostasis and protection from atherosclerosis in mice. In mechanistic studies in mice and primary mouse hepatocytes, we further show that both the FXR phosphorylation at Tyr-67 and Src are important for FGF19-induced FXR binding and transcriptional induction of Scarb1 and Abcg5/8, direct FXR target genes involved in hepatic cholesterol transport for biliary secretion.

Results

FXR-mediated hepatic expression of cholesterol transport genes is blunted by substitution of Phe for Tyr-67 in FXR

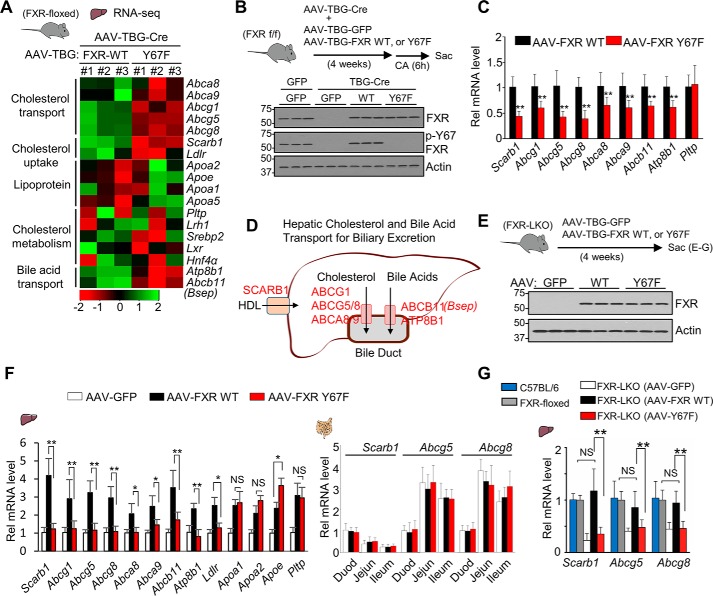

To examine the effect of the FXR phosphorylation on expression of FXR target genes, we examined the changes in gene expression after rescue of FXR expression with liver-specific expression of FXR-WT or phosphorylation-defective (p-defective) Y67F-FXR in mice in which FXR was specifically down-regulated in the liver by expression of hepatocyte-targeting AAV-TBG-Cre (27) in FXR-floxed mice (26) (Fig. 1, A and B). Analysis of previously published RNA-Seq data (16) from these mice revealed that expression of hepatic genes involved in the uptake and transport of cholesterol for hepatobiliary secretion, including an HDL uptake transporter, Scarb1 (8–11); key transporters for biliary cholesterol excretion, including Abcg5 and Abcg8 (8, 9); and BA transporters, Abcb11 (Bsep) and Atp8b1, are up-regulated by hepatic expression of WT-FXR compared with Y67F-FXR (Fig. 1A). To verify these RNA-Seq data, FXR-WT or Y67F-FXR was expressed in the hepatic FXR-down-regulated mice, and the mice were briefly fed cholic acid (CA) chow to activate FXR, which induces FGF15/19 and subsequently phosphorylation of FXR (26) (Fig. 1B, top). FXR-WT or Y67F-FXR was expressed at levels similar to FXR in control FXR-floxed mice, and WT-FXR, but not Y67F-FXR, was phosphorylated at Tyr-67 as reported previously (26) (Fig. 1B, bottom). The mRNA levels of nearly all of the genes involved in cholesterol transport were increased by expression of WT-FXR compared with expression by Y67F-FXR (Fig. 1C). In contrast, mRNA levels of Pltp, an HDL cholesterol metabolism gene, were not increased. These results, together with the role of Y67-FXR phosphorylation in up-regulating Abcb11 (Bsep) (26), a key BA excretion transporter, suggest a potential role for FXR phosphorylation in induction of genes involved in hepatic cholesterol and BA transport into the bile duct for biliary excretion, as illustrated in Fig. 1D.

Figure 1.

FXR-mediated increased expression of hepatic cholesterol transport genes is blocked by mutation of FXR at Tyr-67. A, heat maps of changes in hepatic gene expression in mice expressing Y67F-FXR compared with mice expressing WT-FXR from published RNA-Seq data (26) (n = 3 mice). B and C, FXR-floxed mice were co-infected with AAV-TBG-Cre and either AAV-TBG-GFP or AAV-TBG expressing WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR for 4 weeks (10 mice/group), and mice were fed a 0.5% CA chow for 6 h. B, levels of the indicated proteins were determined by IB. C, the mRNA levels of the indicated genes were measured by RT-qPCR (n = 10). D, diagram of hepatic genes involved in cholesterol transport and efflux for biliary excretion. E–G, FXR-LKO mouse studies. E, FXR-LKO mice were infected with AAV-TBG-GFP or AAV-TBG expressing WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR for 4 weeks (6–7 mice/group). Protein levels of hepatic FXR and p-Y67-FXR determined by IB are shown. F, the mRNA levels of the indicated genes were measured by RT-qPCR in the liver (left) or the duodenum (Duod), jejunum (Jejun), or ileum (right). G, the hepatic mRNA levels of Scarb1 and Abcg5/8 compared with their mRNA levels in control C57BL6 mice (set to 1) and FXR-floxed mice. All values are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars) Statistical significance was measured using the Mann–Whitney test (C) or one-way ANOVA with the Tukey post-test (F and G). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; NS, statistically not significant.

To further determine the role of the Y67-FXR phosphorylation in the regulation of expression of hepatic sterol transport genes, we utilized FXR liver-specific knockout (FXR-LKO) mice and examined the effects of in vivo rescue of FXR expression with WT-FXR or the p-defective Y67F-FXR mutant (Fig. 1E). Compared with control GFP, expression of WT-FXR increased hepatic expression of sterol transport genes, including Scarb1, Ldlr, Abcg5, and Abcg8, and lipoprotein-related genes, Pltp, Apoa1, Apoa2, and Apoe, in the liver (Fig. 1F, left) but did not affect expression of Scarb1, Abcg5, and Abcg8 in the intestine (Fig. 1F, right). Expression of Y67F-FXR, in contrast to FXR-WT, did not result in increased expression of hepatic transport genes, but expression of either FXR-WT or Y67F-FXR resulted in similar increases in expression of lipoprotein-related genes (Fig. 1F, left). Notably, in FXR-LKO mice, reconstitution of WT-FXR expression restored mRNA levels of Scarb1, Abcg5, and Abcg8 to levels similar to those in control C57BL6 mice and in FXR-floxed mice (Fig. 1G). These results demonstrate that phosphorylation of FXR at Tyr-67 is important for expression of hepatic genes involved in cholesterol transport.

Cholesterol-lowering effects of hepatic FXR are blocked by the p-defective Y67F mutation

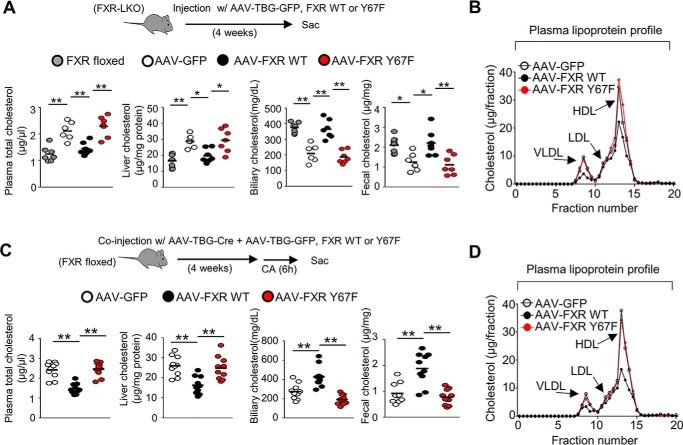

We next tested whether expression of cholesterol transport genes mediated by FXR phosphorylation leads to changes in cholesterol levels in mice. FXR expression was reconstituted with WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR in the liver of FXR-LKO mice, and plasma and tissue cholesterol levels were measured. In vivo rescue of WT-FXR expression mice decreased plasma/liver cholesterol levels and increased biliary/fecal cholesterol levels to levels similar to those in control FXR-floxed mice, and each of these effects was blunted by the p-defective FXR-Y67F mutation (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the decreased plasma cholesterol levels, levels of plasma lipoproteins, particularly very low-density lipoprotein and HDL, were decreased by expression of WT-FXR in FXR-down-regulated mice, but these decreases were attenuated by the Y67F mutation (Fig. 2B). Similar effects on the plasma, liver, biliary, and fecal cholesterol levels and plasma lipoprotein levels were also observed after in vivo rescue of hepatic FXR expression with WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR in the hepatic FXR-down-regulated mice (Fig. 2, C and D). Similar results in both the FXR-LKO mice and the virus-mediated hepatic FXR-down-regulated mice strongly suggest that phosphorylation at a single residue in FXR can impact cholesterol homeostasis in mice.

Figure 2.

Hepatic FXR-mediated cholesterol-lowering effects are blocked by the p-defective Y67F mutation in mice. A and B, FXR-LKO mice were infected with AAV-TBG-GFP or AAV-TBG expressing WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR for 4 weeks (6–7 mice/group). A, cholesterol levels in the plasma, liver, gallbladder, and feces compared with cholesterol levels of control FXR-floxed mice. A horizontal line indicates the mean. B, plasma was subjected to FPLC analysis, and plasma lipoprotein levels were measured in different fractions. C and D, FXR-floxed mice were co-infected with AAV-TBG-Cre and either AAV-TBG-GFP or AAV-TBG expressing WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR for 4 weeks (10 mice/group), and mice were fed a 0.5% CA chow for 6 h, and then plasma and tissue cholesterol levels (C) and plasma lipoprotein levels (D) were measured. Statistical significance was measured using the one-way ANOVA with the Tukey post-test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Down-regulation of Src increases systemic cholesterol levels in mice

Phosphorylation of FXR at Tyr-67 is mediated by FGF15/19-activated Src kinase (26), which suggests that Src may have a role in sterol regulation. To test this possibility, Src was down-regulated in mice by lentiviral expression of Src shRNA (Fig. 3A, top). Down-regulation of Src did not result in changes in protein levels of FXR but p-Y67-FXR levels were decreased (Fig. 3A, bottom), consistent with previous results (26). Down-regulation of Src decreased hepatic expression of all cholesterol transport and metabolism genes tested except for Pltp (Fig. 3B), increased plasma and liver cholesterol levels, and decreased biliary and fecal cholesterol levels (Fig. 3C). Further, plasma lipoprotein cholesterol levels were also increased by down-regulation of Src (Fig. 3D). These results demonstrate that Src has a previously unknown function in sterol regulation, in part by increasing hepatic expression of cholesterol transport genes.

Figure 3.

Down-regulation of Src increases systemic cholesterol levels and decreases hepatic expression of cholesterol transport genes in mice. C57BL/6 mice were infected with lentivirus expressing shRNA for Src for 4 weeks (8 mice/group). A, experimental outline (top). Src, p-Tyr-67 FXR, and FXR levels in the liver determined by IB (bottom, n = 3). B, the mRNA levels of the indicated hepatic genes measured by RT-qPCR (n = 8). C, cholesterol levels in the plasma, liver, gallbladder, and feces (n = 8). A horizontal line indicates the mean. D, plasma pooled from eight mice was subjected to FPLC analysis for lipoproteins as described under “Experimental procedures.” B, all values are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars). Statistical significance was measured using the Mann–Whitney test (B and C). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; NS, statistically not significant.

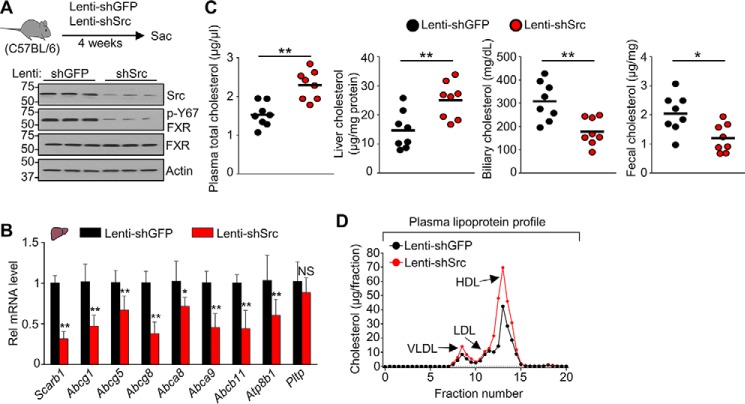

Y67-FXR phosphorylation is protective against atherosclerosis in ApoE-KO mice

Our findings that both Y67-FXR phosphorylation and Src are important for the regulation of cholesterol levels in mice (Figs. 2 and 3) suggested that Y67-FXR phosphorylation might be important for the known protective effects of FXR against atherosclerosis in atherosclerosis-prone mice (4, 5). To test this idea, the effects on atherosclerosis of liver-specific expression of WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR in atherosclerosis-prone ApoE-KO mice chronically fed a Western diet were examined (Fig. 4A). WT-FXR and Y67-FXR, were expressed at similar levels in the mice, and levels of p-Y67-FXR increased for WT-FXR, but not Y67F-FXR as expected (Fig. 4B). In these mice, mRNA levels of most hepatic sterol transport genes, including Scarb1 and Abcg1/5/8, were increased by expression of WT-FXR, and this increase was blocked by the Y67F mutation (Fig. 4C). Expression of WT-FXR resulted in decreased plasma/liver cholesterol levels and increased biliary/fecal cholesterol levels, and each of these changes was blocked by the Y67F mutation (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that phosphorylation of hepatic FXR at Tyr-67 is important for its beneficial effects in atherosclerosis-prone mice.

Figure 4.

Atheroprotective effects by hepatic FXR in ApoE-KO mice are diminished by the p-defective Y67F mutation. ApoE-KO mice that had been fed a Western diet for 24 weeks were infected with AAV-TBG-GFP or AAV-TBG expressing WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR (7 mice/group), and feeding of the Western diet continued until sacrifice 12 weeks later. A, experimental outline. B, protein levels of FXR, p-Y67-FXR, and actin in liver extracts were determined by IB. C, the mRNA levels of the indicated genes were measured by RT-qPCR (n = 7). D, cholesterol levels in the plasma, liver, gallbladder, and feces (n = 7). E and F, from the left image panel to the right image panel, representative cross-sections of Oil Red O staining for atherosclerotic lesions, H&E staining for necrotic core detection, Picrosirius red staining of collagen (red), and immunohistochemical staining with anti-macrophage (F4/80) antibody to detect macrophages (brown) for the aortic sinus (E) or the brachiocephalic artery (F). Right, quantification of plaques, necrotic core, collagen content, and macrophages for the aortic sinus (E) or brachiocephalic artery (F). C, all values are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars). D–F, a horizontal line indicates the mean in the graphs. C–F, statistical significance was measured using the one-way ANOVA with the Tukey post-test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; NS, statistically not significant.

We further examined the effects of FXR on atherosclerosis by examining the histology of the aortic sinus and brachiocephalic artery. The brachiocephalic artery is the first branch of the aortic arch that supplies blood to the head and neck, and atherosclerosis in this artery is the major risk factor for stroke (28). Because cholesterol accumulation in macrophages in the artery wall promotes inflammatory responses (12, 29), infiltration of macrophages was also examined. Expression of WT-FXR resulted in significant decreases in atherosclerotic plaques (Oil Red O staining), necrotic area (hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining), collagen content (Picrosirius red staining), and macrophages (F4/80 antibody) in the atherosclerotic lesions of both the aortic sinus (Fig. 4E) and the brachiocephalic artery (Fig. 4F). Strikingly, each of these FXR-mediated beneficial atheroprotective effects was lost when p-defective Y67F-FXR was expressed, and collagen content and necrotic area in brachiocephalic artery were substantially increased over the control. These findings indicate that phosphorylation of FXR at a single residue can have atheroprotective effects.

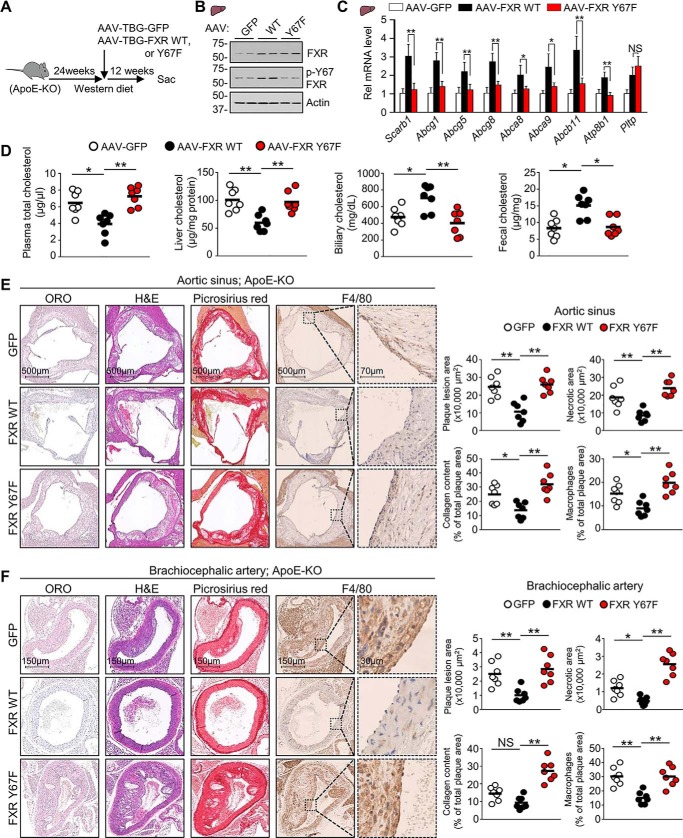

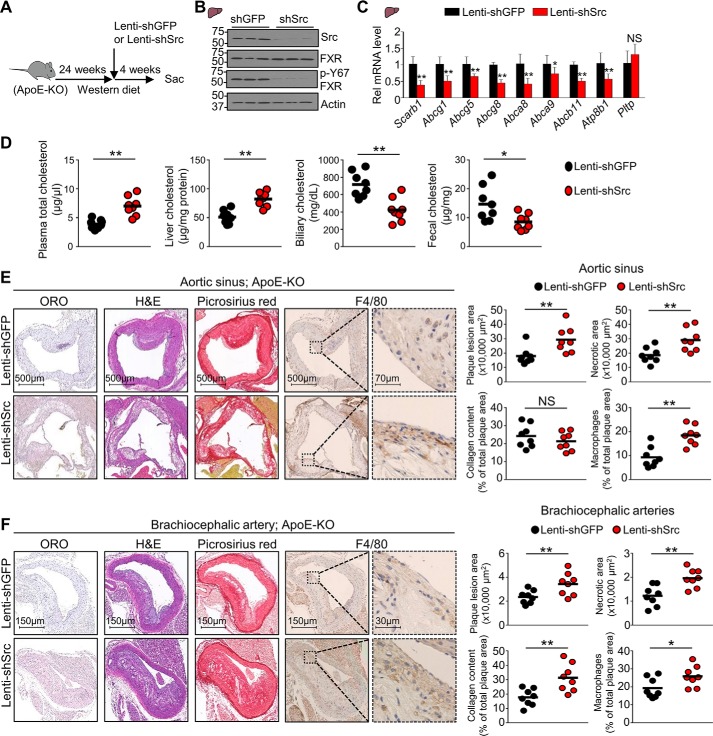

Atherosclerosis in ApoE-KO mice was exacerbated in Src-down-regulated mice

We further examined whether Src also has an atheroprotective role in these ApoE-KO mice fed a chronic Western diet (Fig. 5A). Hepatic expression of FXR was not altered by Src down-regulation, but p-Y67-FXR levels were substantially decreased as expected (Fig. 5B). All of the hepatic cholesterol transport genes examined, except for Pltp, were decreased in ApoE-KO mice by down-regulation of Src (Fig. 5C). Further, plasma and hepatic cholesterol levels were increased, and biliary and fecal cholesterol levels were decreased by Src down-regulation (Fig. 5D). Consistent with the changes in hepatic sterol transport gene expression and cholesterol levels, down-regulation of Src increased atherosclerotic plaques, necrotic areas, and macrophage infiltration in the aortic sinus (Fig. 5E) and brachiocephalic artery (Fig. 5F) and substantially increased collagen content of the plaques in the brachiocephalic artery. These results demonstrate that atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic ApoE-KO mice is exacerbated by down-regulation of Src.

Figure 5.

Atherosclerosis in ApoE-KO mice is exacerbated by down-regulation of Src. ApoE-KO mice that had been fed a Western diet for 24 weeks were infected with lentivirus expressing shRNA for Src, and feeding of the Western diet continued until sacrifice 4 weeks later (8 mice/group). A, experimental outline; B, levels of p-Tyr-67 FXR, FXR, and Src detected by IB in the liver (right, n = 3 mice). C, the mRNA levels of the indicated genes were measured by RT-qPCR (n = 8). D, cholesterol levels in the plasma, liver, gallbladder, and feces (n = 8). E and F, from the left image panel to the right image panel, representative cross-sections of Oil Red O staining for atherosclerotic lesions, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for necrotic core detection, Picrosirius red staining of collagen (in red), and immunohistochemical staining with anti-macrophage (F4/80) antibody to detect macrophages (brown) for the aortic sinus (E) or the brachiocephalic artery (F). Shown is quantification of plaques, necrotic core, collagen content, and macrophage for the aortic sinus (E, right) or the brachiocephalic artery (E, right). C, all values are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars). D–F, a horizontal line indicates the mean in the graphs. C–F, statistical significance was measured using the Mann–Whitney test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; NS, statistically not significant.

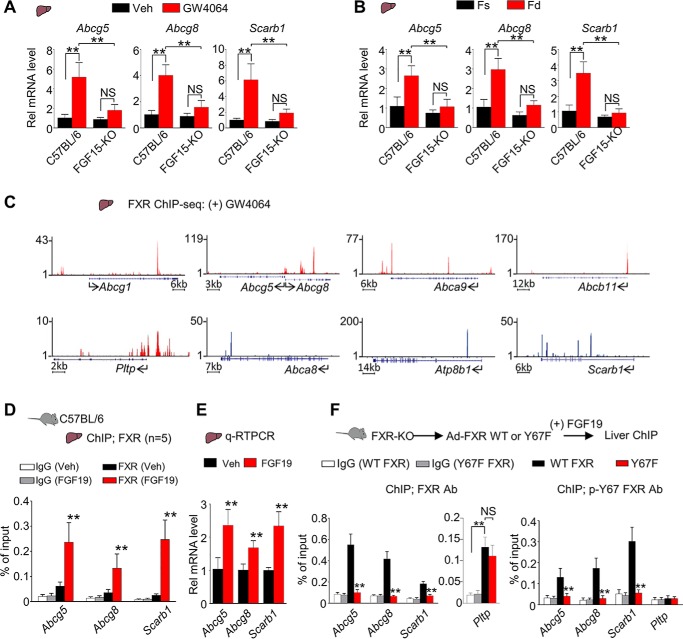

Endogenous FGF15 signaling is important for induction of Scarb1 and Abcg5/8, after feeding or FXR activation

Our findings indicated that both Y67-FXR phosphorylation and Src are important for lowering cholesterol levels in mice in part through transcriptional induction of hepatic cholesterol transport genes (Figs. 1–3). Because Y67-FXR phosphorylation is mediated by FGF15/19 (26), an intestinal hormone that is induced by the bile acid–activated FXR in the late fed state (3), we further examined the role of endogenous FGF15 signaling in the regulation of hepatic genes involved in sterol metabolism. FGF15-KO mice and control C57BL/6 mice were treated with an FXR agonist, GW4064, or refed after fasting, and expression of sterol transport genes was measured. Hepatic expression of Scarb1 and Abcg5/8 was increased after GW4064 treatment (Fig. 6A) or feeding (Fig. 6B) in control C57BL/6 mice, but these effects were severely blunted in FGF15-KO mice. These results suggest that increased expression of Scarb1 and Abcg5/8 after feeding or GW4064 treatment depends on physiologically induced endogenous FGF15 signaling in mice.

Figure 6.

Endogenous FGF15 signaling is required for induction of direct FXR targets, Scarb1 and Abcg5/8, after FXR activation or feeding in mice. A and B, the hepatic mRNA levels of the indicated genes measured by RT-qPCR of C57BL/6 or FGF15-KO mice that were either treated daily with vehicle or GW4064 (100 mg/kg) for 2 days (n = 4–5) (A) or fasted for 12 h (Fs) or fed for 6 h (Fd) after fasting (n = 5) (B). C, UCSC genome browser displays of binding of FXR to representative genes involved in sterol transport and metabolism in mice treated with GW4064 from published FXR liver ChIP-Seq data (30, 31). The y axis shows the numbers of mapped sequence tags. Gene positions are indicated at the bottom of each display with the arrows indicating the direction of transcription and the start site. D and E, C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) were fasted for 12 h and injected via the tail vein with FGF19 (1 mg/kg) or vehicle for 2 h. D, FXR occupancy in liver was detected by ChIP at the indicated genes. E, the mRNA levels were detected by RT-qPCR. F, FXR-KO mice were infected with adenovirus expressing WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR for 4 weeks and injected via the tail vein with FGF19 (1 mg/kg) for 2 h. Occupancy of FXR (left) and p-Tyr-67 FXR (right) in the liver was detected by ChIP analysis at the indicated genes (n = 5). A–B and D–F, all values are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars). Statistical significance was measured using the Mann–Whitney test (E) or two-way ANOVA with the Tukey post-test (A, B, D, and F). **, p < 0.01; NS, statistically not significant.

To understand the mechanisms by which the FGF19-induced phosphorylation of FXR up-regulates genes involved in sterol transport and metabolism, we first tested whether these genes are direct targets of FXR. In published hepatic FXR ChIP-Seq data from mice treated with GW4064 (30, 31), FXR binding peaks were detected at numerous cholesterol transport genes (Fig. 6C). Consistent with this observation, in mouse liver ChIP assays, occupancy of FXR at Abcg5, Abcg8, and Scarb1 (Fig. 6D) and the mRNA levels of these genes were increased by FGF19 treatment (Fig. 6E).

To determine whether occupancy of FXR at sterol transport genes depended on Y67-FXR phosphorylation, WT-FXR or Y67F-FXR was expressed in FXR-KO mice, and liver ChIP assays were performed. FXR occupancy at Abcg5/8 and Scarb1 was detected with antibodies to either FXR or specifically p-Y67-FXR in mice expressing WT-FXR treated with FGF19 (Fig. 6F). Occupancy of FXR at these genes was not detected in mice expressing Y67F-FXR (Fig. 6F), suggesting that Y67-FXR phosphorylation is required for binding to these genes. In contrast, at Pltp, similar occupancy of FXR in both groups of mice expressing WT or Y67F-FXR was detected (Fig. 6F, center), but occupancy of p-Y67-FXR was not detected (Fig. 6F, right), indicating that phosphorylation is not required for FXR binding to Pltp. This result is consistent with the increases in mRNA levels of Pltp, a direct FXR target (32), by expression of either Y67F-FXR or WT-FXR (Fig. 1, C and F). These results suggest that FXR binding at Scarb1 and Abcg5/8, but not at Pltp, requires the Tyr-67 phosphorylation and further suggest that the FXR phosphorylation contributes to gene-selective regulation of hepatic genes involved in cholesterol transport and metabolism.

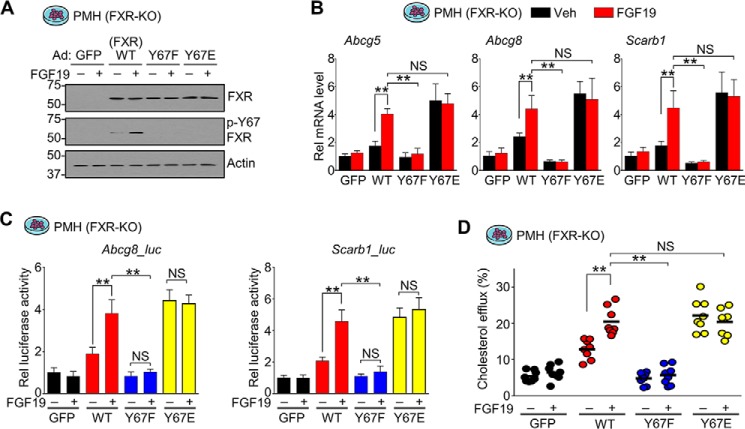

FGF19-induced sterol transport gene expression and cholesterol efflux from hepatocytes are dependent on Y67-FXR phosphorylation

To further understand the mechanism by which the FXR phosphorylation at Tyr-67 regulates hepatic sterol transport genes, we examined the effects of expression of p-mimic and p-defective Tyr-67 mutants on expression of Abcg5/8 and Scarb1 in primary mouse hepatocytes derived from FXR-KO mice to avoid confounding effects of endogenous FXR (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Y67-FXR phosphorylation is important for FGF19-induced cholesterol transport gene expression and cholesterol excretion/efflux from hepatocytes. Hepatocytes were isolated from FXR-KO mice and transfected with expression plasmids for FLAG-WT-FXR, FLAG-Y67F-FXR, FLAG-Y67E-FXR, or GFP. After 48 h, cells were treated with vehicle or 50 ng/ml FGF19 for 2 h (A and B), 12 h (C), or 6 h (D). A, FXR and p-Tyr-67 FXR levels in the cells detected by IB; B, mRNA levels of the indicated genes measured by RT-qPCR (n = 5). C, luciferase reporter assay. Luciferase activities were normalized to β-gal activity (n = 4). D, cholesterol excretion/efflux assay. Cholesterol efflux was measured as described under “Experimental procedures.” A, B, and D, all values are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars). D, a horizontal line indicates the mean. A, B, D, and E, statistical significance was measured using the two-way ANOVA with the Tukey post-test (B–D). **, p < 0.01; NS, statistically not significant.

Treatment with FGF19 increased mRNA levels of Abcg5/8 and Scarb1 in hepatocytes expressing WT-FXR, but these effects were blunted by the Y67F mutation (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the mRNA levels were increased even in untreated cells by expression of the p-mimic Y67E mutant, and FGF19 treatment did not further increase the levels (Fig. 7B). Consistent with the changes in mRNA levels, in luciferase reporter assays, expression of WT-FXR increased transactivation of Abcg8-Luc and Scarb1-Luc, which was further increased by FGF19 treatment, whereas expression of Y67F-FXR did not increase transactivation, and FGF19 had no effect (Fig. 7C). Notably, expression of the p-mimic mutant, Y67E-FXR, increased transactivation independently of FGF19 treatment, similarly to that of WT-FXR in FGF19-treated cells, and FGF19 did not further increase transactivation (Fig. 7C). These results indicate that the phosphorylation of FXR at Tyr-67 is required for induction of Abcg5/8 and Scarb1 in hepatocytes.

Because Y67-FXR phosphorylation is important for hepatic expression of Abcg5 and Abcg8, cholesterol transporters for biliary excretion (10, 11), we further examined the effect of the FXR phosphorylation on cholesterol efflux from primary hepatocytes. Consistent with the changes in expression of Abcg5 and Abcg8, expression of WT-FXR increased cholesterol efflux, and FGF19 treatment further increased the efflux (Fig. 7D). Expression of the p-defective Y67F-FXR did not increase cholesterol efflux with or without FGF19 treatment, whereas the p-mimic Y67E-FXR increased efflux independent of FGF19 treatment (Fig. 7D). These findings suggest that Y67-FXR phosphorylation is important for FGF19-mediated induction of Abcg5/8 and Scarb1 and increased cholesterol excretion from hepatocytes.

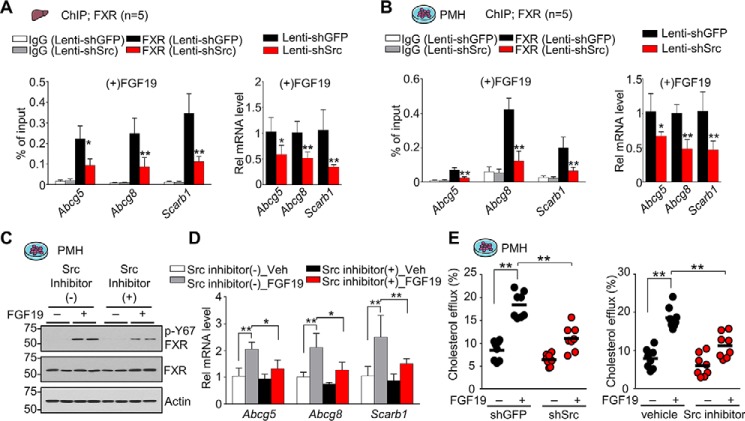

Src is important for FGF19-induced sterol transport gene expression and cholesterol efflux from hepatocytes

We further examined the effects of down-regulation or inhibition of Src on FXR occupancy at Abcg5, Abcg8, and Scarb1 genes and gene expression. In mice (Fig. 8A) or primary mouse hepatocytes (Fig. 8B) treated with FGF19, shRNA-mediated down-regulation of Src reduced occupancy of FXR at Abcg5/8 and Scarb1 genes and decreased expression of these genes. Similarly, in primary mouse hepatocytes, FGF19 treatment increased mRNA levels of these genes, and the FGF19-mediated increases were blocked by treatment with a Src inhibitor, dasatinib, which, as expected, decreased levels of p-Y67-FXR (Fig. 8, C and D). Consistent with these transcriptional changes, the FGF19-mediated increase in cholesterol efflux from hepatocytes was largely blocked by either down-regulation or inhibition of Src (Fig. 8E). These results from hepatocytes and mice, together, strongly suggest that Src is required for FGF19-mediated induction of direct FXR targets, Abcg5/8 and Scarb1, and increased cholesterol efflux transport for hepatobiliary excretion.

Figure 8.

Src important for FGF19-induced cholesterol transport gene expression and cholesterol excretion/efflux from hepatocytes. A, C57BL/6 mice were infected with lentivirus expressing shRNA for Src for 4 weeks and injected with FGF19 (1 mg/kg) for 2 h. FXR occupancy in liver was detected by ChIP at the indicated genes (left), and mRNA levels were detected by RT-qPCR (right) (n = 5). B, PMHs were infected with lentivirus expressing shRNA for Src for 72 h and treated with 50 ng/ml FGF19 for 2 h. FXR occupancy was detected by ChIP at the indicated genes (left), and mRNA levels were detected by RT-qPCR (right) (n = 5). C and D, PMHs were pretreated with vehicle or 1 nm dasatinib for 1 h and then treated with vehicle or 50 ng/ml FGF19 for 2 h. C, the p-Tyr-67 FXR and FXR levels were determined by IB. D, the mRNA levels of the indicated genes measured by RT-qPCR (n = 8). E, PMHs from C57BL/6 mice were infected with lentivirus expressing shRNA for Src for 72 h and treated with 50 ng/ml FGF19 for 6 h (left) or were pretreated with vehicle or 1 nm dasatinib for 2 h and then treated with vehicle or 50 ng/ml FGF19 for 6 h (right). Cholesterol efflux from hepatocytes was measured as described under “Experimental procedures.” A–D, all values are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars). E, a horizontal line indicates the mean. A–E, statistical significance was measured using the two-way ANOVA with the Tukey post-test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Discussion

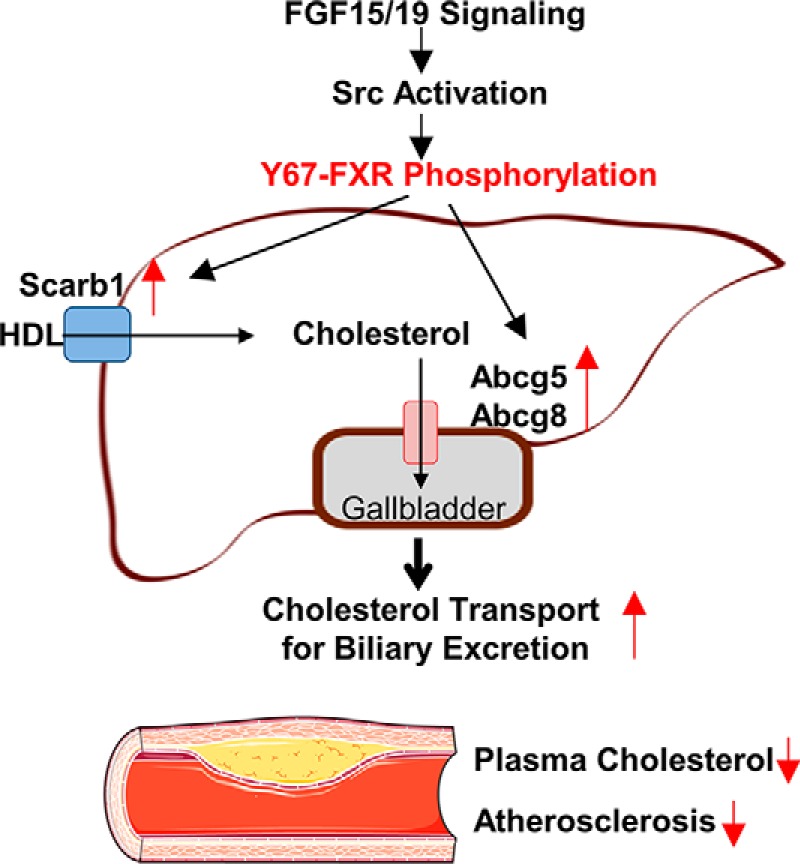

In this study, utilizing in vivo rescue of FXR expression with FXR-WT and a p-defective Y67F-FXR mutant in FXR-LKO and hepatic FXR-down-regulated mice and down-regulation of Src, we demonstrate that phosphorylation of hepatic FXR at a single residue by Src can impact cholesterol homeostasis in mice. FXR, phosphorylated at Tyr-67 by FGF15/19 signaling–activated Src, mediates the transcriptional induction of genes important for hepatic uptake and transport of cholesterol for hepatobiliary excretion, which contributes to decreases in plasma cholesterol levels and protection against atherosclerosis (model in Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Model. Phosphorylation of hepatic FXR at a single residue, Tyr-67, mediated by FGF15/19 signaling–activated c-Src is important for the transcriptional induction of hepatic sterol transport genes, including Scarb1, Abcg5, and Abcg8, as shown in this study, and the resultant increased cholesterol efflux from hepatocytes for biliary excretion. This hepatic FGF19-Src-FXR phosphorylation signaling cascade contributes to decreased cholesterol levels and protects against atherosclerosis in mice.

In vivo rescue of FXR-WT in the liver of FXR-LKO– or FXR–down-regulated mice resulted in decreased levels of plasma and liver cholesterol and increased cholesterol excretion in the feces, but these FXR-mediated sterol-lowering effects were not observed after rescue with of p-defective Y67F-FXR. The similar results in both the chronic FXR-LKO mice, in which developmental compensation could occur, and the acute AAV-TBG-Cre virus-mediated down-regulation of hepatic FXR in FXR-floxed mice, in which unwanted viral effects could occur, strongly support the conclusion that phosphorylation of hepatic FXR at a single residue, Tyr-67, plays an important role in the regulation of cholesterol levels in mice. Consistent with these effects on regulating sterol levels, expression of FXR decreased atherosclerosis in atherosclerosis-prone ApoE-KO mice, whereas expression of the p-defective Y67F-FXR had little beneficial effect.

Our studies provide an explanation for previous studies indicating that treatment with an FXR agonist, GW4064, increased hepatic expression of Abcg5, Abcg8, and Scarb1 in mice in vivo, but not in cultured hepatic cells (9). Our present studies show that phosphorylation of FXR by intestinal FGF15/19 is required for expression of these hepatic cholesterol transport genes. Thus, activation of FXR in mice, which induces intestinal FGF15/19, would be expected to induce the genes in vivo, but not in the cultured cells due to the absence of the intestinal FGF15/19.

FXR has been shown to regulate cholesterol levels via multiple pathways. FXR promotes hepatic cholesterol transport for biliary excretion, intestinal cholesterol absorption, and transintestinal cholesterol excretion via modulation of BA composition (6, 8, 33). In addition, FXR-induced SHP decreases cholesterol levels via inhibition of de novo sterol biosynthesis and intestinal absorption (20, 26). FXR also regulates plasma HDL levels through induction of microRNA-144 (34). In the present study, we identify a molecular signaling pathway for regulation of cholesterol levels via a hepatic FGF15/19-Src-FXR phosphorylation signaling cascade. Utilizing FGF15-KO mice, we further demonstrated that physiologically induced endogenous FGF15 signaling by feeding has a role in the regulation of expression of hepatic sterol transport genes. BA levels quickly increase after a meal, resulting in FXR induction of intestinal FGF19, and plasma FGF15/19 levels peak about 2–3 h after feeding, so that FGF15/19 is considered a late-fed state hormone (35, 36). Thus, FXR-induced intestinal FGF15/19 feeds back to activate hepatic FXR via Src-mediated phosphorylation, which contributes to sustained FXR function in the transcriptional regulation of cholesterol metabolism in the late fed state when the hepatic BA levels have declined.

Recently, we demonstrated that Y67-FXR phosphorylation is important for function of FXR in the regulation of hepatic BA levels, including transcriptional repression of BA synthetic genes, Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 (26). Inhibition of the conversion of cholesterol into BAs could potentially result in a detrimental increase in hepatic cholesterol levels. The present study, however, reveals that the FXR phosphorylation by FGF15/19-activated Src decreases hepatic cholesterol levels in part by induction of Scarb1 and Abcg5/8, genes involved in RCT. Although we did not directly examine the effect of Src-mediated FXR phosphorylation on RCT in vivo, our studies are consistent with a role for this phosphorylation in RCT. Both FXR and Src mediated increased biliary and fecal cholesterol levels, decreased plasma and liver cholesterol levels, and increased expression of cholesterol transport genes in mice and increased cholesterol excretion from primary mouse hepatocytes. These results support the conclusion that the FXR phosphorylation mediated by Src regulates sterol levels in part via promoting hepatic cholesterol transport for biliary excretion.

An intriguing finding in this study is the demonstration of a previously unknown function for c-Src in cholesterol regulation and protection against atherosclerosis. Src is a well-known proto-oncogene and a target for cancer treatment (37). During cancer therapy, treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, including dasatinib, an inhibitor of Src, increases the risk for cardiovascular disease and heart failure (38). Intriguingly, we observed that atherosclerosis in ApoE-KO mice was exacerbated in Src-down-regulated mice, which could underlie the increased risk in cancer patients treated with Src inhibitors. Thus, the decreased FXR functions as a result of Src inhibition would lead to increased sterol levels, as shown in the current study, which could also contribute to the cardiovascular risk of Src inhibitor therapy.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that phosphorylation of hepatic FXR at a single residue can impact whole-body cholesterol homeostasis and protect against atherosclerosis in mice and further show that Src has a previously unknown function in regulating cholesterol levels. FXR is the molecular target of obeticholic acid, a Food and Drug Administration–approved drug for liver fibrosis, and other FXR agonists and FGF19 analogues are under clinical trials for the treatment of metabolic disorders (1, 39, 40). Because PTMs of nuclear receptors like FXR have gene-selective effects (22, 24, 26), as is also suggested by the present studies, targeting the phosphorylation of FXR by FGF15/19 signaling–activated Src may provide more specific therapeutic options for hypercholesterolemia-related cardiovascular disease.

Experimental procedures

Materials and reagents

Antibodies for FXR (1:5,000, sc-13063) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., and antibodies for β-actin (1:10,000, sc-4970) and Src (1:3,000, sc-2108) were from Cell Signaling. M2 antibody (1:3,000, F3165) was purchased from Sigma. F4/80 (AP10243PU-M) was obtained from Acris Antibodies. Antibodies for p-Tyr-67–specific FXR were produced commercially (1:10,000, Abmart, Inc.) and validated in FXR-KO mice (26). ON-TARGETplus mouse siRNAs for Src (L-040877) were purchased from GE Healthcare Dharmacon, Inc. GW4064 was obtained from Tocris Bioscience. A Src inhibitor (dasatinib monohydrate) was obtained from Selleckchem. Purified FGF19 was provided by Dr. H. Eric Xu (Van Andel Research Institute, Grand Rapids, MI). In the present study, human FGF19 was used because mouse FGF15 is less stable, both FGF15 and FGF19 have similar metabolic effects, and FGF19 has been utilized in previous studies (20, 26, 41).

Animal experiments

FXR-floxed mice were provided by Drs. Kristina Schoonjans and Johan Auwerx (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland). For virus-mediated liver-specific down-regulation of FXR, AAV serotype 8 (AAV8) vectors containing a liver hepatocyte-specific TBG promoter were used. Eight-week-old FXR-floxed male mice were injected via the tail vein with 100 μl of a mixture of AAV-TBG-Cre and either AAV8-TBG-GFP, AAV8-TBG-FXR WT, or AAV8-TBG-Y67F-FXR at 5 × 1010 virus particles/mouse. Four weeks later, mice were briefly fed 0.5% CA-supplemented chow for 6 h to activate FXR signaling. FXR-LKO mice were generated by breeding of homozygous FXR-floxed mice with albumin-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory). Eight-week-old FXR-LKO male mice were injected via the tail vein with AAV8-TBG-GFP, AAV8-TBG-FXR WT, or AAV8-TBG-Y67F-FXR viruses, and 4 weeks later, mice were fasted for 4–6 h before sacrifice to avoid metabolic fluctuation. For Src down-regulation in mice, lentivirus expressing control shRNA or shRNA for Src (VectorBuilder, 0.5–1.0 × 109 IU/ml in 100 μl of saline) was injected into C57BL6 mice via the tail vein, and after 1 month, plasma and tissues were collected. ApoE-KO male mice (Jackson Laboratory) that had been fed a Western diet (40–45% fat and 0.2% cholesterol, Harlan Teklad, TD88137) for 6 months were injected with viruses, feeding with the Western diet was continued, and mice were sacrificed 1–3 months later. FGF15-KO mice have been described in previous studies (42). FGF15-KO mice and C57BL/6 mice were fasted for 12 h or refed for 6 h after fasting or treated daily with vehicle or GW4064 (100 mg/kg) for 2 days, and livers were collected.

Evaluation of atherosclerosis

Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and their hearts and brachiocephalic arteries were perfused with PBS. After fixation with 10% formaldehyde overnight, the hearts and brachiocephalic artery were embedded in OCT compound for frozen section preparation. The aortic sinus and brachiocephalic artery were sectioned at a thickness of 10 μm. For IHC studies, frozen sections were stained with either Oil Red O (Abcam, ab150678), H&E (Vector Laboratories, H-3502), or Picrosirius red (Abcam, ab150681) or were incubated with the F4/80 antibody overnight at 4 °C, which was detected with the rabbit-specific HRP/DAB Detection IHC Kit (Abcam). The sections were imaged with a NanoZoomer scanner (Hamamatsu).

Cholesterol measurement

Liver, biliary, fecal, and plasma cholesterol levels were determined using a cholesterol quantitation kit (MAK043, Sigma). For measuring plasma cholesterol levels, plasma was prepared by spinning freshly collected blood at 1,500 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and stored at −80 °C until use. For fractionation of plasma lipoproteins, plasma (100 μl) was subjected to FPLC in the Proteomics Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Primary mouse hepatocytes (PMHs)

PMHs were isolated from FXR-KO mice by collagenase (0.8 mg/ml; Sigma) perfusion through the portal vein of mice anesthetized with isoflurane. Hepatocytes were filtered through a cell strainer (100-μm nylon, BD Biosciences), washed with M199 medium, centrifuged through 45% Percoll (Sigma), and cultured in M199 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. PMHs from FXR-KO mice were infected with Ad-FXR WT or Y67F-FXR, and then the cells were incubated in serum-free medium overnight and treated with FGF19 for the indicated times.

ChIP assays

Minced muse livers or primary mouse hepatocytes were washed twice with PBS and then incubated with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at 37 °C. Glycine was added to 125 mm for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were resuspended in hypotonic buffer and lysed by homogenization. Nuclei were isolated by centrifugation and resuspended in sonication buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mm EDTA, and 1% SDS). The samples were sonicated four times with 10-s intervals using a QSonica XL-2000 instrument at power output setting 8. Then the chromatin sample was precleared by incubation with a Protein G–Sepharose slurry and immunoprecipitated using 1–1.5 μg of antibody or IgG as control. The immune complexes were collected by incubation with a Protein G–Sepharose slurry containing salmon sperm DNA for 1 h. The beads were washed with 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, three times, containing successively 150 mm NaCl, 500 mm NaCl, or 0.25 m LiCl, and then bound chromatin was eluted and incubated overnight at 65 °C to reverse the cross-linking. DNA was isolated for qPCR. Sequences of primers are given in Table S1.

Luciferase reporter assays

DNA fragments at Abcg8 and Scarb1 that contained FXR peaks detected by ChIP-Seq were amplified by PCR from mouse genomic DNA and cloned into the pGL3-basic-Luc vector (Promega). PMHs from FXR-KO mice were transfected with plasmids, and 72 h later, the cells were treated with vehicle or 50 ng/ml FGF19 for 12 h. Luciferase activities were normalized to β-gal activities.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen), RT-qPCR was performed, and the amount of mRNA for each gene was normalized to that of 36B4 mRNA. Sequences of primers are given in Table S2.

Cholesterol efflux assays

Cellular cholesterol excretion/efflux from isolated PMHs was measured using fluorescently labeled cholesterol according to the manufacturer's instructions (Abcam, ab196985). Fluorescence was measured in a fluorescent microplate reader equipped with a filter for excitation/emission = 482/515 nm 4 h after the addition of the fluorescently labeled cholesterol for the calculation of the efflux.

IB analysis

Liver tissues or cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and homogenized in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm DTT, and 0.1% SDS). Proteins in the cell lysates were separated and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, which were blocked and incubated with primary antibodies, followed by incubation with secondary HRP-linked antibody.

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined by Student's two-tailed t test, Mann–Whitney test, or one- or two-way ANOVA with the Tukey post-test for single or multiple comparisons as appropriate. Whenever relevant, the assumptions of normality were verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, or D'Agostino–Pearson omnibus test. p values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Study approval

All animal use and biosafety protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care and Biosafety Committees of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and were in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Author contributions

S. B., H. J., and J. K. designed research; S. B., H. J., J. C., Y. K., and D. K. performed experiments; S. B., H. J., J. C., Y. K., D. K., and B. Kemper analyzed data; Y. K. performed genomic analyses; B. Kong and G. G. provided key materials for the study; and S. B., H. J., B. Kemper, and J. K. wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Kristina Schoonjans and Johan Auwerx (Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland) for providing FXR-floxed mice. We also thank Dr. H. Eric Xu (Van Andel Research Institute, Grand Rapids, MI) for providing purified FGF19 protein.

This study was supported by American Heart Association (AHA) Postdoctoral Fellowship 17POST33410223 (to S. B.), American Diabetes Association (ADA) Postdoctoral Fellowship 1-19-PDF-117 (to J. C.), AHA Scientist Development Award 16SDG27570006 (to Y. K.), AHA Post-doctoral Fellowship 14POST20420006 (to D. K.), and National Institutes of Health Grants DK062777 and DK095842 and ADA Innovative Basic Science Grant 1-16-IBS-156 (to J. K. K.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Tables S1 and S2.

- BA

- bile acid

- Abcg5/8

- ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 5/8

- ApoE

- apolipoprotein E

- Bsep

- bile salt excretion pump

- FGF

- fibroblast growth factor

- FXR

- farnesoid X receptor

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- HDL

- high-density lipoprotein

- IB

- immunoblotting

- IHC

- immunohistochemistry

- LKO

- liver-specific knockout

- Pltp

- phospholipid transfer protein

- PMH

- primary mouse hepatocyte

- RCT

- reverse cholesterol transport

- Scarb1

- scavenger receptor class B member 1

- SHP

- small heterodimer partner

- KO

- knockout

- PTM

- post-translational modification

- p-defective

- phosphorylation-defective

- p-mimic

- phosphorylation mimic

- p-

- phosphorylated

- CA

- cholic acid

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

References

- 1. de Aguiar Vallim T. Q., Tarling E. J., and Edwards P. A. (2013) Pleiotropic roles of bile acids in metabolism. Cell Metab. 17, 657–669 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Calkin A. C., and Tontonoz P. (2012) Transcriptional integration of metabolism by the nuclear sterol-activated receptors LXR and FXR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 213–224 10.1038/nrm3312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kliewer S. A., and Mangelsdorf D. J. (2015) Bile acids as hormones: the FXR-FGF15/19 pathway. Dig. Dis. 33, 327–331 10.1159/000371670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lambert G., Amar M. J., Guo G., Brewer H. B. Jr., Gonzalez F. J., and Sinal C. J. (2003) The farnesoid X-receptor is an essential regulator of cholesterol homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2563–2570 10.1074/jbc.M209525200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hanniman E. A., Lambert G., McCarthy T. C., and Sinal C. J. (2005) Loss of functional farnesoid X receptor increases atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 46, 2595–2604 10.1194/jlr.M500390-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang Y., Yin L., Anderson J., Ma H., Gonzalez F. J., Willson T. M., and Edwards P. A. (2010) Identification of novel pathways that control farnesoid X receptor-mediated hypocholesterolemia. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3035–3043 10.1074/jbc.M109.083899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sinal C. J., Tohkin M., Miyata M., Ward J. M., Lambert G., and Gonzalez F. J. (2000) Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell 102, 731–744 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu Y., Li F., Zalzala M., Xu J., Gonzalez F. J., Adorini L., Lee Y. K., Yin L., and Zhang Y. (2016) Farnesoid X receptor activation increases reverse cholesterol transport by modulating bile acid composition and cholesterol absorption in mice. Hepatology 64, 1072–1085 10.1002/hep.28712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Repa J. J., Berge K. E., Pomajzl C., Richardson J. A., Hobbs H., and Mangelsdorf D. J. (2002) Regulation of ATP-binding cassette sterol transporters ABCG5 and ABCG8 by the liver X receptors α and β. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18793–18800 10.1074/jbc.M109927200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yu L., Gupta S., Xu F., Liverman A. D., Moschetta A., Mangelsdorf D. J., Repa J. J., Hobbs H. H., and Cohen J. C. (2005) Expression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 is required for regulation of biliary cholesterol secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8742–8747 10.1074/jbc.M411080200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Repa J. J., and Mangelsdorf D. J. (2002) The liver X receptor gene team: potential new players in atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 8, 1243–1248 10.1038/nm1102-1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tall A. R., Yvan-Charvet L., Terasaka N., Pagler T., and Wang N. (2008) HDL, ABC transporters, and cholesterol efflux: implications for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 7, 365–375 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosenson R. S., Brewer H. B. Jr., Davidson W. S., Fayad Z. A., Fuster V., Goldstein J., Hellerstein M., Jiang X. C., Phillips M. C., Rader D. J., Remaley A. T., Rothblat G. H., Tall A. R., and Yvan-Charvet L. (2012) Cholesterol efflux and atheroprotection: advancing the concept of reverse cholesterol transport. Circulation 125, 1905–1919 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kir S., Beddow S. A., Samuel V. T., Miller P., Previs S. F., Suino-Powell K., Xu H. E., Shulman G. I., Kliewer S. A., and Mangelsdorf D. J. (2011) FGF19 as a postprandial, insulin-independent activator of hepatic protein and glycogen synthesis. Science 331, 1621–1624 10.1126/science.1198363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Byun S., Kim Y. C., Zhang Y., Kong B., Guo G., Sadoshima J., Ma J., Kemper B., and Kemper J. K. (2017) A postprandial FGF19-SHP-LSD1 regulatory axis mediates epigenetic repression of hepatic autophagy. EMBO J. 36, 1755–1769 10.15252/embj.201695500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim Y. C., Seok S., Byun S., Kong B., Zhang Y., Guo G., Xie W., Ma J., Kemper B., and Kemper J. K. (2018) AhR and SHP regulate phosphatidylcholine and S-adenosylmethionine levels in the one-carbon cycle. Nat. Commun. 9, 540 10.1038/s41467-018-03060-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fu L., John L. M., Adams S. H., Yu X. X., Tomlinson E., Renz M., Williams P. M., Soriano R., Corpuz R., Moffat B., Vandlen R., Simmons L., Foster J., Stephan J. P., Tsai S. P., and Stewart T. A. (2004) Fibroblast growth factor 19 increases metabolic rate and reverses dietary and leptin-deficient diabetes. Endocrinology 145, 2594–2603 10.1210/en.2003-1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schumacher J. D., Kong B., Pan Y., Zhan L., Sun R., Aa J., Rizzolo D., Richardson J. R., Chen A., Goedken M., Aleksunes L. M., Laskin D. L., and Guo G. L. (2017) The effect of fibroblast growth factor 15 deficiency on the development of high fat diet induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 330, 1–8 10.1016/j.taap.2017.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luo J., Ko B., Elliott M., Zhou M., Lindhout D. A., Phung V., To C., Learned R. M., Tian H., DePaoli A. M., and Ling L. (2014) A nontumorigenic variant of FGF19 treats cholestatic liver diseases. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 247ra100 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim Y. C., Byun S., Zhang Y., Seok S., Kemper B., Ma J., and Kemper J. K. (2015) Liver ChIP-seq analysis in FGF19-treated mice reveals SHP as a global transcriptional partner of SREBP-2. Genome Biol. 16, 268 10.1186/s13059-015-0835-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim Y. C., Byun S., Seok S., Guo G., Xu H. E., Kemper B., and Kemper J. K. (2019) Small heterodimer partner and fibroblast growth factor 19 inhibit expression of NPC1L1 in mouse intestine and cholesterol absorption. Gastroenterology 156, 1052–1065 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kemper J. K., Xiao Z., Ponugoti B., Miao J., Fang S., Kanamaluru D., Tsang S., Wu S. Y., Chiang C. M., and Veenstra T. D. (2009) FXR acetylation is normally dynamically regulated by p300 and SIRT1 but constitutively elevated in metabolic disease states. Cell Metab. 10, 392–404 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim D. H., Kwon S., Byun S., Xiao Z., Park S., Wu S. Y., Chiang C. M., Kemper B., and Kemper J. K. (2016) Critical role of RanBP2-mediated SUMOylation of small heterodimer partner in maintaining bile acid homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 7, 12179 10.1038/ncomms12179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim D. H., Xiao Z., Kwon S., Sun X., Ryerson D., Tkac D., Ma P., Wu S. Y., Chiang C. M., Zhou E., Xu H. E., Palvimo J. J., Chen L. F., Kemper B., and Kemper J. K. (2015) A dysregulated acetyl/SUMO switch of FXR promotes hepatic inflammation in obesity. EMBO J. 34, 184–199 10.15252/embj.201489527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Berrabah W., Aumercier P., Gheeraert C., Dehondt H., Bouchaert E., Alexandre J., Ploton M., Mazuy C., Caron S., Tailleux A., Eeckhoute J., Lefebvre T., Staels B., and Lefebvre P. (2014) Glucose sensing O-GlcNAcylation pathway regulates the nuclear bile acid receptor farnesoid X receptor (FXR). Hepatology 59, 2022–2033 10.1002/hep.26710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Byun S., Kim D. H., Ryerson D., Kim Y. C., Sun H., Kong B., Yau P., Guo G., Xu H. E., Kemper B., and Kemper J. K. (2018) Postprandial FGF19-induced phosphorylation by Src is critical for FXR function in bile acid homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 9, 2590 10.1038/s41467-018-04697-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seok S., Kim Y. C., Byun S., Choi S., Xiao Z., Iwamori N., Zhang Y., Wang C., Ma J., Ge K., Kemper B., and Kemper J. K. (2018) Fasting-induced JMJD3 histone demethylase epigenetically activates mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 3144–3159 10.1172/JCI97736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weber C., and Noels H. (2011) Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat. Med. 17, 1410–1422 10.1038/nm.2538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tall A. R., and Yvan-Charvet L. (2015) Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 104–116 10.1038/nri3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas A. M., Hart S. N., Kong B., Fang J., Zhong X. B., and Guo G. L. (2010) Genome-wide tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor binding in mouse liver and intestine. Hepatology 51, 1410–1419 10.1002/hep.23450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee J., Seok S., Yu P., Kim K., Smith Z., Rivas-Astroza M., Zhong S., and Kemper J. K. (2012) Genomic analysis of hepatic farnesoid X receptor (FXR) binding sites reveals altered binding in obesity and direct gene repression by FXR. Hepatology 56, 108–117 10.1002/hep.25609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Urizar N. L., Dowhan D. H., and Moore D. D. (2000) The farnesoid X-activated receptor mediates bile acid activation of phospholipid transfer protein gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39313–39317 10.1074/jbc.M007998200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. de Boer J. F., Schonewille M., Boesjes M., Wolters H., Bloks V. W., Bos T., van Dijk T. H., Jurdzinski A., Boverhof R., Wolters J. C., Kuivenhoven J. A., van Deursen J. M., Oude Elferink R. P. J., Moschetta A., Kremoser C., et al. (2017) Intestinal farnesoid X receptor controls transintestinal cholesterol excretion in mice. Gastroenterology 152, 1126–1138.e6 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Aguiar Vallim T. Q., Tarling E. J., Kim T., Civelek M., Baldán Á., Esau C., and Edwards P. A. (2013) MicroRNA-144 regulates hepatic ATP binding cassette transporter A1 and plasma high-density lipoprotein after activation of the nuclear receptor farnesoid X receptor. Circ. Res. 112, 1602–1612 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lundåsen T., Gälman C., Angelin B., and Rudling M. (2006) Circulating intestinal fibroblast growth factor 19 has a pronounced diurnal variation and modulates hepatic bile acid synthesis in man. J. Intern. Med. 260, 530–536 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01731.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Katafuchi T., Esterházy D., Lemoff A., Ding X., Sondhi V., Kliewer S. A., Mirzaei H., and Mangelsdorf D. J. (2015) Detection of FGF15 in plasma by stable isotope standards and capture by anti-peptide antibodies and targeted mass spectrometry. Cell Metab. 21, 898–904 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parsons S. J., and Parsons J. T. (2004) Src family kinases, key regulators of signal transduction. Oncogene 23, 7906–7909 10.1038/sj.onc.1208160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lenihan D. J., and Kowey P. R. (2013) Overview and management of cardiac adverse events associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncologist 18, 900–908 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. De Magalhaes Filho C. D., Downes M., and Evans R. (2016) Bile acid analog intercepts liver fibrosis. Cell 166, 789 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Degirolamo C., Sabbà C., and Moschetta A. (2016) Therapeutic potential of the endocrine fibroblast growth factors FGF19, FGF21 and FGF23. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 15, 51–69 10.1038/nrd.2015.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fu T., Choi S. E., Kim D. H., Seok S., Suino-Powell K. M., Xu H. E., and Kemper J. K. (2012) Aberrantly elevated microRNA-34a in obesity attenuates hepatic responses to FGF19 by targeting a membrane coreceptor β-Klotho. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16137–16142 10.1073/pnas.1205951109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kong B., Huang J., Zhu Y., Li G., Williams J., Shen S., Aleksunes L. M., Richardson J. R., Apte U., Rudnick D. A., and Guo G. L. (2014) Fibroblast growth factor 15 deficiency impairs liver regeneration in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 306, G893–G902 10.1152/ajpgi.00337.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.