Abstract

Intraocular medulloepithelioma is a nonhereditary neoplasm of childhood arising from primitive medullary epithelium. It most often involves the ciliary body. Most patients present between 2 and 10 years of age with loss of vision, pain, leucocoria, or conjunctival congestion. The mass appears as a grey-white ciliary body lesion with intratumoral cysts. Presence of a neoplastic cyclitic membrane with extension to retrolental region is characteristic. Secondary manifestations like cataract and neovascular glaucoma may be present in up to 50% and 60% patients, respectively. These could be the first signs for which, unfortunately, about 50% patients undergo surgery before recognition of the hidden tumor. Systemic correlation with pleuropulmonary blastoma (DICER1 gene) has been documented in 5% cases. Histopathology shows primitive neuroepithelial cells arranged as cords closely resembling the primitive retina. Histopathologically, the tumor is classified as teratoid (containing heteroplastic elements) and nonteratoid (containing medullary epithelial elements), each of which are further subclassified as benign or malignant. Retinoblastoma-like and sarcoma-like areas may be seen within the tissue. The treatment modality depends on tumor size and extent of invasion. For small localized tumors (≤3-4 clock hours), conservative treatments with cryotherapy, plaque radiotherapy, or partial lamellar sclerouvectomy (PLSU) have been used. Plaque brachytherapy is generally preferred for best tumor control. Advanced and extensive tumors require enucleation. Rare use of intra-arterial and intravitreal chemotherapy has been employed. Systemic prognosis is favorable, but those with extraocular extension and orbital involvement show risk for local recurrence and metastatic disease, which can lead to death.

Keywords: Ciliary epithelium, ciliary body, diktyoma, medulloepithelioma, non-teratoid, teratoid, tumor

Intraocular medulloepithelioma is a unique embryonal tumor that arises from the primitive medullary epithelium along the inner stratum of the optic cup.[1,2,3] In an early report, it was termed “carcinome primitif” by Badel and Lagrange in 1892.[4] “Teratoneuroma” was a term coined by Verhoeff in 1904 due to the heteroplastic tissues discerned within the tumor.[5] Subsequently, Fuchs, in 1908, renamed the tumor as “diktyoma” (diktyon means net in Greek) because of the microscopic interlacing bands of neuroepithelial cells, and a network of medullary epithelial cords.[3] The term “medulloepithelioma” was introduced by Grinker[6] in 1931 owing to the histological resemblance of the tumor to the neuroepithelium of the embryonic neural tube. This was based on the pioneering work of Bailey and Cushing[7] on the medulloepithelioma of the central nervous system. This term is currently accepted by the World Health Organization. Table 1 shows the classification of epithelial tumors of nonpigmented ciliary body epithelium.

Table 1.

Classification of epithelial tumors of nonpigmented ciliary body epithelium

| Congenital |

|---|

| Glioneuroma |

| Medulloepithelioma |

| 1. Nonteratoid |

| Benign |

| Malignant |

| 2. Teratoid |

| Benign |

| Malignant |

| Acquired |

| Nonpigmented ciliary epithelium Hyperplasia (Fuchs adenoma) |

| Adenoma |

| Adenocarcinoma |

Adapted from[1] Saunders T, Margo CE. Intraocular medulloepithelioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:212-6

Origin

Medulloepithelioma is a congenital tumor of the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium. The human retina is derived from the optic cup, which is an outgrowth of medullary epithelium of medullary tube.[8] At 6 weeks of gestation, the inner and outer walls of the optic cup have identical appearance and is called the embryonal retina. This tissue appears similar to the medullary epithelium of brain. The anterior portion of the optic cup eventually goes on to form the epithelium of iris and ciliary body. Medulloepithelioma has an appearance very similar to this primitive retina and medullary epithelium of brain tissue seen before 6 weeks of gestation.[8]

Medulloepithelioma most often is detected in children and rarely in adults. Zimmerman[2] hypothesized that medulloepithelioma in children is derived from incompletely differentiated embryonic ciliary epithelium (congenital medulloepithelioma). In rare cases in adults, medulloepithelioma is thought to arise from fully differentiated ciliary epithelium after undergoing non-neoplastic reactive hyperplasia or pseudoadenomatous hyperplasia. Fuchs[3] believed that adult medulloepitheliomas represent neoplastic transformation of hyperplastic ciliary epithelium, triggered by inflammation or trauma. Medulloepithelioma diagnosed in adults could represent delayed transformation of a pre-existent retinal anlage.[9,10,11] Most cases in adults are histopathologically malignant, suggesting a delayed malignant transformation of a pre-existing lesion.[11,12,13] Benign medulloepithelioma in adults is detected following decades of gradual growth, eventually manifesting clinically. Medulloepithelioma can rarely arise from the optic disc, iris, and retinal stalk.[5,14,15,16]

Epidemiology

There is paucity of large-scale population-based studies on this tumor owing to its rarity, making it difficult to estimate its incidence. One of the largest series was by Broughton and Zimmerman,[9] who reported a series of 56 patients of medulloepithelioma from Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, USA. A recent relatively large study was published on 41 patients pooled from two dedicated oncology institutions in Hyderabad, India, and Philadelphia, USA.[17] Other smaller studies from Shields et al.[12] in Philadelphia, USA on 10 cases and Canning et al.[18] in London, England on 16 cases have been described.

Age of presentation is typically between 2 and 10 years,[9,12,17,18] with 75-90% of tumors manifesting in the first decade of life.[17] However, there are well documented cases of medulloepithelioma manifesting in adulthood.[2,19,20,21] Overall, the age of presentation has been known to vary between 6 months and 79 years.[9,12,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] There appears to be no gender or racial predilection.[9,12,17,18] It is typically unilateral, with no preference for either eye.[9,12,17,18] Coexistence of persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous has been reported in 20% of cases by Broughton and Zimmerman.[9]

Clinical Features

Patients are initially asymptomatic. Small tumors rarely cause functional changes significant enough to be noticed. Often patients do not present until the tumors are large enough to be seen through the pupil or cause symptomatic secondary effects. Quite frequently, patients are treated for secondary effects first even before the discovery of the mass.[9,12,17] Symptomatic patients present with loss of vision, leukocoria, pain, visible intraocular mass, or red eye. Vision loss may be due to lens subluxation, cataract, retrolental membrane, or neovascular glaucoma.

On examination, the mass appears irregular grey-white to pink, located at the region of the ciliary body [Fig. 1]. Multiple intratumoral cysts are evident in more than 50% of patients.[9,12,17] These cysts can break free from the main tumor and be found floating in the anterior chamber or vitreous cavity or settled in the anterior chamber angle. The tumor may contain chalky, grey-white areas representing the presence of cartilage.[12] In rare cases, the tumor is pigmented.[24] The tumor may also show vessels running across its surface or episcleral feeder vessels.

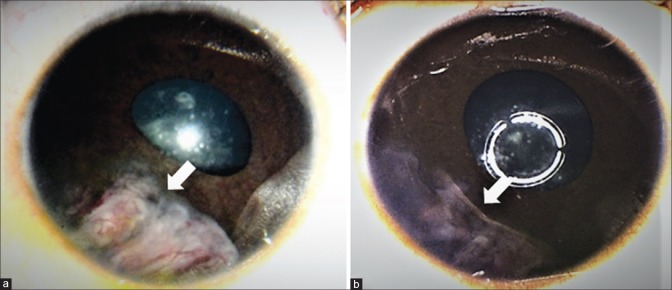

Figure 1.

Clinical features of medulloepithelioma in (a) 2-year-old girl who presented with translucent white mass (arrow) with intrinsic vascularity and iris neovascularisation. (b) In the ciliary body was a beige-white mass with loss of zonule, representing medulloepithelioma

The zonular fibers adjacent to the tumor are often sparse or are lost. This causes a notch or coloboma of the adjoining lens. It may also lead to lens subluxation with an accompanying sectoral or occasionally total cataract. The iris may show a localized bowing due to underlying tumor. Other features include corectopia, ectropion uveae or sectoral or diffuse neovascularisation of the iris.[17] The ciliary body adjacent to the tumor may show long ciliary processes and is often covered by a neoplastic cyclitic membrane.[9,12] It is speculated that this membrane represents migration of the neoplastic tissue over the anterior hyaloid. Medulloepithelioma has a tendency to grow along the scaffold of the posterior lens capsule and the anterior hyaloid forming a vascular retrolental membrane.[9,12,17,19,25] Retrolental membrane is found in 23-60% of patients.[12,17]

Typical secondary effects produced by the ciliary body medulloepithelioma include cataract with or without lens subluxation and unilateral neovascular glaucoma. A review of ciliary body medulloepithelioma by Broughton and Zimmerman[9] and Canning et al.[18] revealed glaucoma in 48-50% of cases and cataract in 26-50%. In a clinic-based review of 10 cases by Shields et al.,[12] neovascular glaucoma was present in 60% of cases and cataract in 50% of cases. In a review of 41 cases, glaucoma was present in 44% and cataract was present in 46%.[17] Shields et al. documented a strong tendency of this tumor to induce neovascular glaucoma. They indicated that a child presenting with unilateral neovascular glaucoma and normal fundus must be thoroughly evaluated for medulloepithelioma. Intraretinal involvement is uncommon.[26] Kivelä and Summanen termed this phenotype as “retinoinvasive medulloepithelioma.”[26] Retinoinvasive phenotype was believed to be associated with concurrent glaucoma, chronicity, and older age. Other rare secondary manifestations include uveitis, hyphema, retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, invasion of the optic nerve, and rarely extraocular extension of the tumor.[12] The typical clinical features with their relative frequency are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Intraocular Medulloepithelioma: Clinical features

| Symptoms |

| Leucocoria (20%) |

| Loss of vision (27%) |

| Painful red eye (20%) |

| Asymptomatic (17%) |

| Strabismus (12%) |

| Signs |

| Grey-white Ciliary body mass with cysts |

| Lens |

| Loss of zonules and Subluxation (27%) |

| Notch or coloboma (20%) |

| Cataract (46%) - Sectoral or Total |

| Iris |

| Localised bowing/bulge |

| Neovascularisation (51%) |

| Corectopia (29%) |

| Ectropion uveae (29%) |

| Retrolental Neoplastic cyclitic membrane (51%) |

| Secondary glaucoma (44%) |

| Neovascular glaucoma (83%) |

| Angle closure glaucoma (17%) |

| Vitreous haemorrhage (5%) |

| Retinal detachment (22%) |

| Extra ocular tumor extension (10%) |

Data adapted from[17] Kaliki S., Shields C.L., Eagle Jr. R.C et al. Ciliary body medulloepithelioma: Analysis of 41 cases. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, pp. 2552-2559

Systemic Associations

DICER-1 gene (OMIM 601200) is a member of the ribonuclease III family. This gene is an autosomal dominant trait located at 14q32.13.[27] It manifests as a familial cancer syndrome, known as Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Family Tumor and Dysplasia Syndrome (PPB-FTDS). The reported tumors with this mutation include pleuropulmonary blastoma (67% have DICER-1 germline mutation), cystic nephroma (73% have DICER-1 germline mutation), ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor (57% have DICER-1 germline mutation), and thyroid hyperplasia or goiter (32% women, 13% men).[28] Medulloepithelioma, medulloblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, colon cancer, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, thyroid cancer, and papillary Wilms’ tumor (nephroblastoma) are also known associations. Pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) is a rare malignant neoplasm of the lung that manifests with seemingly innocuous lung cysts that arise from embryonal cells. It presents typically prior to 6 years of age.[29] PPB is the pulmonary analogue of commoner childhood embryonal tumors such as retinoblastoma, medulloblastoma, Wilms tumor, and neuroblastoma among others.[29]

Specific association of ciliary body PPB and medulloepithelioma has been identified recently. Priest et al.[30] reviewed 299 cases enrolled in the International PPB Registry and 300 patients from outside the registry. They reported four patients with medulloepithelioma and PPB, possibly DICER1 syndrome. Ciliary body medulloepithelioma was identified in 3 patients with PPB and in a parent of a child with PPB. Since then, there have been several other reports of this association.[31,32] Two patients with a history of PPB who were referred with ocular symptoms were found to have ciliary body medulloepithelioma.[17] On the basis of these findings, it seems that <1% of patients with PPB manifest ciliary body medulloepithelioma, and 5% of patients with medulloepithelioma have a history of PPB.[17] More recently, somatic mutations of KMT2D along with DICER1 have been identified in intraocular medulloepitheliomas, although the mechanism of involvement of these genes in the pathogenesis of this disease have not been clearly outlined.[33]

There have been reports of ciliary body medulloepithelioma in the irradiated eye of a child with bilateral hereditary retinoblastoma[34] and in a child with pineoblastoma.[35] This finding indicates medulloepithelioma may rarely accompany the retinoblastoma spectrum of diseases. Whether any genetically determined mechanism is common to ciliary body medulloepithelioma and retinoblastoma remains to be investigated.

Imaging

Characteristic feature of medulloepithelioma consists of a ciliary body mass with intratumoral cysts. Ultrasound B-scan shows heterogeneous, highly echogenic mass localized to the ciliary body and specifically within the epithelium, demonstrating intratumoral, irregular cystic areas [Fig. 2].[36] This tumor may or may not demonstrate calcification, depending if there is cartilage within the tumor, and this further complicates differentiation of intraocular medulloepithelioma from retinoblastoma.[12,17] Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) and ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) [Figs. 2 and 3] delineate the exact radial and circumferential extent and the height of the ciliary body mass and demonstrate intratumoral cysts, neoplastic cyclitic membrane, anterior chamber cysts and sequelae, such as lens subluxation. UBM, due to its higher resolution, is a good modality to delineate the tumor and document the dimensions for serial follow-up of the patient.[37] Fluorescein angiography shows large, branching arteries and veins arising from the ciliary body tumor peripherally and haphazardly criss-crossing within the retrolenticular tissue [Fig. 3].[38] One study on fluorescein angiography demonstrated a vascular stalk extending to the tumor from an adjacent detached retina.[36]

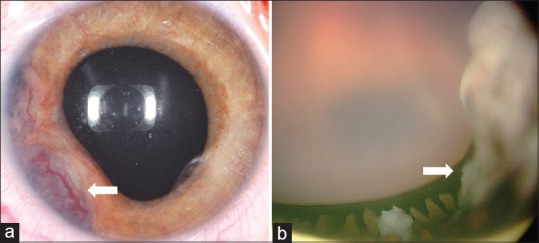

Figure 2.

Ultrasonography of medulloepithelioma demonstrates (a) B-scan showing a heterogenous echodense mass in ciliary body with intra-tumoral cyst (arrow). (b) Ultrasound biomicroscopy better delineates the solid mass, echodense foci of cartilage, and intra-tumoral cysts (arrow)

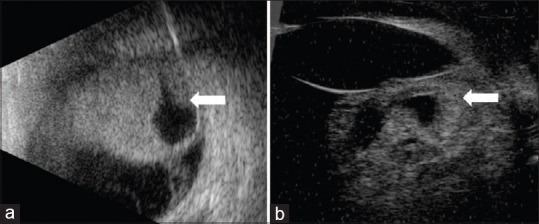

Figure 3.

A 5-year-old girl with (a) leukocoria was noted to have iris neovascularization and retrolental neoplastic cyclitic membrane with vessels (arrow) arising from the ciliary body. (b) Ultrasound biomicroscopy depicted the ciliary body mass with intratumoral cysts, lens subluxation and neoplastic cyclitic membrane (arrow). Fluorescein angiography in the (c) early and (d) late frames highlight the vessels in the retrolental membrane. Following enucleation, the (e) gross specimen reveals an amelanotic ciliary body tumour (arrow) with pigmented areas and with neoplastic cyclitic membrane (arrowhead). Histopathology (f) shows tubules and nests of basophilic neoplastic cells (black arrow) surrounded by loose mucopolysaccharide rich matrix. (Hematoxyline eosin stain; 2.5x magnification)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the standard preoperative investigative modality.[36] The tumor appears as a heterogeneous mass composed of both solid and cystic components arising from a lateral retrolental location. The tumor is usually isointense to mildly hyperintense to vitreous on T1-weighted images on MRI, with avid enhancement with contrast. Linear or irregular soft tissue that extends posteriorly along the ciliary body region with abnormal signal intensity of the vitreous body, and the presence of intratumoral cysts are all features that can be identified at MRI.[39] Scleral invasion, extraocular and optic nerve extension identifiable on MRI can help in the management and in predicting possibility of metastatic disease.[39]

Histopathology

Medulloepithelioma has a distinctive microstructural architecture.[1] It comprises of pseudostratified primitive neuroepithelial cells surrounded by hyaluronic acid-rich hypocellular stroma [Fig. 3].[1] This arrangement closely resembles medullary epithelium of the developing neurosensory retina or embryonic neural tube before the fourth month of gestation.[1,8] The stroma is akin to the vitreous.[1] The neuroepithelial surface facing the hypocellular stroma is lined by a thin basement membrane that corresponds to the internal limiting membrane of the neurosensory retina.[1] The opposite surface is lined by a series of terminal bars, which corresponds to the external limiting membrane.[1] When medullary epithelium folds so that the vitreous surface faces inwards, it creates cysts with stroma rich in hyaluronic acid.[1] There may be multiple such proliferating cysts some of which can detach from the main tumor and relocate into the anterior chamber or vitreous cavity.[1] Area between the anastomosing cords of neuroepithelial may be filled in with sheets of undifferentiated neuroblasts, indistinguishable by light microscopy from retinoblastoma cells.[1] Flexner-Wintersteiner and Homer Wright rosettes can be found among the undifferentiated neuroblasts but as compared with those in retinoblastoma, the rosettes in medulloepithelioma, are often larger and more cellular.[1] Features more specific to medulloepithelioma are neuroepithelial tubules and absence of calcification.[1] Although medulloepithelioma often is said to arise from the region of nonpigmented ciliary body epithelium, foci of intrinsically pigmented tumor cells are relatively common.[1,9,17]

Based on histopathological findings, intraocular medulloepithelioma is classified as nonteratoid or teratoid, and benign or malignant.[2,9] Nonteratoid medulloepithelioma comprises purely of primitive medullary epithelium. Teratoid medulloepithelioma exhibits heteroplastic elements, commonly mature hyaline cartilage. Sometimes neuroglial (brain-like) tissue or rhabdomyoblasts (striated muscle) may be seen in addition to the proliferation of the neuroepithelial elements.[1,2,9,17] Occasionally, the entire tissue may be comprised of heteroplastic elements making it nearly indistinguishable from teratoma, sarcoma, or choristoma. Malignant medulloepithelioma is diagnosed based on four features as described by Zimmerman et al.:[9]

Retinoblastoma-like elements (sheets of neuroblastic cells among the cords) with or without rosettes

Sarcoma-like elements

Pleomorphism and high mitotic index

Invasion into adjacent uvea, lens, sclera, cornea, optic nerve, or orbit.

Immunohistochemical markers have different patterns of reactivity depending on whether the tissue of interest is neuroepithelial or heteroplastic. The nonteratoid component is typically positive for vimentin and neuron-specific enolase.[14,40,41] Limited and conflicting results have been reported for chromogranin, synaptophysin, glial fibrillary acid protein, S100 protein, and HMB-45.[14,40,41,42] Immunohistochemistry for pancytokeratins and cytokeratin (CK) 18, with no reactivity for CK7, CK20, and epithelial membrane antigen has been described.[40]

In large case series of medulloepithelioma in the literature, 50-63% tumors were nonteratoid (10-31% benign and 19-40% malignant) and 38-50% were teratoid (0-31% benign and 19-50% malignant).[9,12,17,18] Most common malignant features were high mitotic activity (60%) and retinoblastoma-like differentiation (37%).[17] The distinction between benign and malignant tumors may be blurred and it is postulated to represent a spectrum rather than two distinct entities. The fact that adults are more likely to present with malignant tumor might represent a natural progression of the disease.[42] Intraocular medullpepithelioma shares many histopathologic features with medulloepithelioma of the central nervous system, but its overall prognosis for life is considerably better.[43]

Differential Diagnosis

Medulloepithelioma can be misdiagnoised as retinoblastoma.[44] Neovascular glaucoma, ciliary body invasion, anterior chamber seeds or presence of a total cataract may lead to misdiagnosis. The age of presentation must be taken into consideration. Most patients of retinoblastoma present before 6 years of age with predominantly posterior segment findings of grey-white to yellow intraocular retinal mass, which may be unilateral or bilateral and may be associated with tumor seeds.[45] Presence of calcification is characteristic of retinoblastoma but intratumoral cartilage in medulloepithelioma may show a similar picture. Coats disease is another differential diagnosis, which presents with unilateral retinal vascular telangiectasia with exudative retinal detachment. Lack of involvement of ciliary body serves as an important differentiating feature. Retrolental neoplastic cyclitic membrane serves as an important feature to distinguish medulloepithelioma from retinoblastoma and Coats disease. On fluorescein angiography, the neoplastic cyclitic membrane shows rapid filling of large, haphazard vessels emanating from the ciliary body across the hyaloid face, whereas in total retinal detachment from retinoblastoma or Coats disease, the vessels are regular, organized, and emanate from the closed central funnel of the detachment out toward the ciliary body region.[36,38]

Persistent fetal vasculature (PFV) or persistant hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV) has been reported to be associated with about 20% of cases of medulloepithelioma.[9] The retrolental membrane in medulloepithelioma can be confused with PHPV.[46] Unlike the retrolental fibrovascular plaque of PHPV, membrane in medulloepithelioma represents a sheet of neoplastic tissue that has migrated from the main tumor across the anterior vitreous face, using the hyaloid as a scaffold. The cells comprising this membrane multiply slowly and produce collagen, leading to opacification of the neoplastic cyclitic membrane which can then closely resemble PHPV.[12] The vessels on this membrane arise from the periphery and are not associated with a vascular stalk extending to the disc.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is also one of the tumors that may mimic medulloepithelioma. It presents as spontaneous hyphema and fleshy diffuse involvement of the iris. It most often is restricted to the iris and is occasionally associated with skin manifestations of the disease. Intraocular toxocariasis is a chronic granulomatous inflammatory response caused by Toxocara larvae. Patients are generally older than 5 years and often have a history of contact with dogs. Serological studies may support the diagnosis.[36] Acquired tumors of the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium such as adenomatous hyperplasia (Fuchs adenoma), adenoma, and carcinoma must be considered as differential diagnosis in adults. Metastatic carcinoma to the ciliary body and ciliochoroidal melanoma are also possibilities in adults.

Management

Treatment options for ciliary body medulloepithelioma include cryotherapy, plaque radiotherapy, external beam radiotherapy, local resection, and enucleation.[9,12,17,47,48,49,50,51] Enucleation is a standard treatment for advanced intraocular medulloepithelioma with large tumors and neovascular glaucoma.[9,12,17] Enucleation must be performed with minimal manipulation with due care taken to prevent accidental perforation and spillage of tumor cells into the orbit. Extended enucleation or orbital exenteration may be required for cases with orbital extension.

Smaller tumors (not exceeding 3-4 clock hours) may be treated with cryotherapy, radiotherapy, or local resection. Cryotherapy can be used for small or recurrent tumors. Triple freeze-thaw cryotherapy is recommended. Local resection by partial lamellar sclerouvectomy (PLSU) can be considered as an option for small circumscribed tumors (3-4 clock hours). It is, however, technically demanding and is associated with high tumor recurrence rate. Broughton and Zimmerman[9] reported 80% (8 of 10) of the patients exhibited tumor recurrence after iridocyclectomy, ultimately requiring enucleation. In a study of 10 patients by Shields et al.,[12] 6 were managed primarily by local resection, all with ultimate tumor recurrence requiring additional treatment. Four of these eyes had to be enucleated, one was exenterated and another treated with cryotherapy. Local tumor resection is reported to have up to 50% recurrence rate.[17]. Local tumor recurrence may be attributed to residual subclinical tumor that was not included in excision.

Plaque brachytherapy is a viable alternative for small to medium size tumors. There have been reports of successful treatment with I-125 and Ru-106 plaque radiotherapy.[49,50,51] The procedure is shorter, technically less demanding and produces better results than local resection. Ang et al.[50] reported on 6 cases of medulloepithelioma treated with plaque brachytherapy, as primary treatment in 5 cases and secondary treatment in 1 case. An apex dose of 44 Gy was delivered. At a mean follow-up of 59 months (range, 12–210 months), tumor control was achieved in 5 eyes (83%) with globe salvage in 4 eyes (67%), whereas 2 eyes were enucleated. Of the 2 enucleations, one eye had persistent hypotony, retinal detachment and neovascularization of the iris leading to enucleation and histopathology showed completely regressed tumor. The other patient with enucleation showed a noncontiguous tumor recurrence following Co-60 plaque brachytherapy. No patient had evidence of metastases or death at the last follow-up visit. Poon et al.[51] reported on the effectiveness of Ru 106 plaque brachytherapy in 5 patients. An apex dose of 40-50 Gy was delivered. All brachytherapy-treated tumors had a height of <5 mm, and 80% regressed. One patient showed minimal (0.2 mm) but stable reduction in height of the tumor. During 26 months follow-up, none of the eyes showed recurrence or required enucleation. Standard external beam radiotherapy is less effective for intraocular medulloepithelioma.[17] It has mainly been used at a dose of 45-50 Gy as an adjuvant therapy for the treatment of tumors extending into the orbit or metastatic tumors. Table 3 summarizes the modalities of treatment used in major studies on medulloepithelioma.[9,12,17,18]

Table 3.

Intraocular medulloepithelioma: Treatment modalities

| Broughton and Zimmerman[9] (1978) n=56 eyes n (%) | Canning et al.[18] (1988) n=16 eyes n (%) | Shields et al.[12] (1996) n=10 eyes n (%) | Kaliki et al.[17] (2013) n=35 eyes n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radical | ||||

| Primary Enucleation | 38 (68) | 12 (75) | 4 (40) | 21 (60) |

| Secondary Enucleation | 8 (14) | 4 (25) | 4 (40) | 5 (14) |

| Primary Exenteration | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Secondary Exenteration | 5 (9) | 1 (2) | 1 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Conservative | ||||

| Cryotherapy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Partial Lamellar sclerouvectomy | 10 (18) | 4 (25) | 6 (60) | 8 (23) |

| Primary Plaque Brachytherapy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) |

| Secondary Plaque brachytherapy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (20) | 2 (6) |

| External beam Radiotherapy (Adjuvant) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | 1 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Chemotherapy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

The role of systemic chemotherapy is not well established for medulloepithelioma. However, there have been reports of metastatic medulloepithelioma successfully treated with chemotherapy with vincristine, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and carboplatin in conjunction with radiotherapy and surgery.[52,53] These cases have documented decrease in size of tumor while on chemotherapy with ultimate stable disease control. The utility of chemotherapy as primary treatment of intraocular medulloepithelioma remains to be further explored. Fig. 4 shows one patient managed with systemic chemotherapy and plaque radiotherapy for local control.

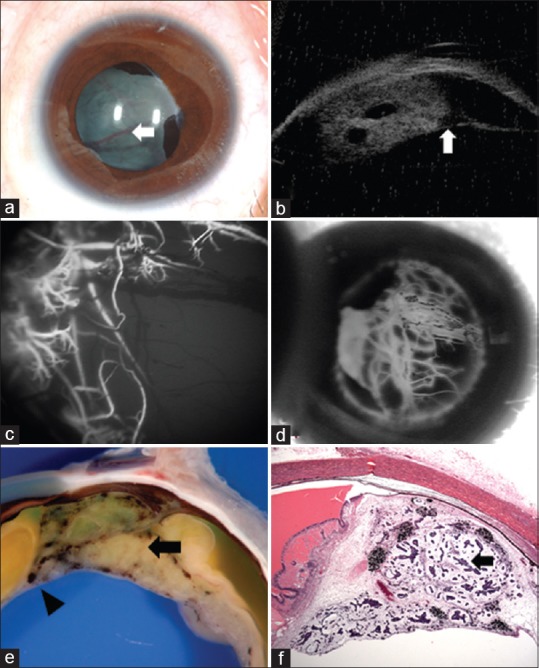

Figure 4.

A 2-year-old boy with (a) fleshy vascularised mass in his right eye, confirmed on fine needle aspiration biopsy to have ciliary body medulloepithelioma with angle involvement. He was treated with 6 cycles of systemic chemotherapy (vincristine, etoposide and carboplatin) followed by plaque brachytherapy and showed stable regression of tumour 6 months post treatment (b)

Prognosis

Patients very often present many months after the first appearance of symptoms. Medulloepithelioma is often misdiagnosed as cataract, glaucoma and uveitis, representing the secondary manifestations of the disease.[54,55] Often these patients are treated for these conditions for a long time, with some patients undergoing surgical intervention. These are the causes for significant delay in diagnosis and create possible routes for extraocular extension of tumor that drastically alters the prognosis of these patients.

Zimmerman[9] found that up to 20% of cases were misdiagnosed and surgically treated for other conditions with procedures such as lensectomy or glaucoma drainage procedures and the diagnosis delayed for up to 1 year. Shields[12] reported 6 patients in whom there was a delay in diagnosis. One patient had undergone penetrating diathermy because of a diagnosis of “vascular hamartoma” failing recognition of the tumor. The penetrating diathermy may have created a route for the subsequent transscleral migration of tumor into the orbit. In the remaining patients, there was a delay of 3-18 months from the initial ocular examination to the recognition of the tumor. Three of these patients underwent surgery for cataract, glaucoma, or suspected PHPV, and the tumor remained undetected. Prior treatment due to initial misdiagnosis was reported in 16 patients (39%) in a recent large multicentric series.[17]

Metastatic disease and tumour-related death from ciliary body medulloepithelioma is uncommon, unless there is extraocular extension or central nervous system involvement.[1,9,12,17] Tumors confined to the globe have excellent prognosis, with a 5-year survival of 90–95% after enucleation.[56,57] Extension of the tumor into the extrascleral orbital soft tissues dramatically increases the rate of metastatic disease and recurrence, resulting in poor overall prognosis. This is often treated with orbital exenteration and chemotherapy as opposed to enucleation alone. Follow-up data on the 56 patients reported by Broughton and Zimmerman[2,9] was present in 33 patients (23 were lost to follow-up) and this revealed tumor-related deaths in 4 (12%) patients. Of the original 56 tumors, 37 were histologically malignant and 10 had extraocular spread. All 4 tumor-related deaths occurred in patients with malignant tumors with extraocular extension detected on histopathologic examination. In 3 cases, death was preceded by orbital recurrence. Three patients died with intracranial extension and the fourth with distant metastasis.

Three cases with local regional metastasis were noted, all in patients with extraocular extension of tumor in the conjunctiva or orbit.[17] Two had delay in diagnosis of about 39 months and had undergone multiple surgical interventions before presentation and one of them presented with congenital medulloepithelioma with extraocular extension. Median time to metastasis from diagnosis of extraocular extension was 9 months. Tumor-related death occured mostly in cases with orbit involvement or intracranial extension. However, there have been cases of orbital extension with metastatic disease that have been successfully managed with neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy, aggressive surgery, and radiotherapy,[52,53]

Summary

In summary, medulloepithelioma is a rare intraocular tumor of childhood that arises from primitive medullary epithelium. This tumor hides for months to years in the ciliary body region and produces secondary features of glaucoma and cataract, leading to surgery and later discovery of the tumor. Ophthalmologists must exercise due caution in children presenting with unilateral secondary glaucoma, cataract and iris neovascularization and must advise imaging such as UBM to detect medulloepithelioma. Although smaller tumors can be conservatively managed with cryotherapy or plaque brachytherapy, larger tumors with neovascular glaucoma may be best treated with primary enucleation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Saunders T, Margo CE. Intraocular medulloepithelioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:212–6. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2010-0669-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmerman LE. Verhoeff's “terato-neuroma”. A critical reappraisal in light of new observations and current concepts of embryonic tumors. The Fourth Frederick H. Verhoeff Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;72:1039–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs E. Growths and tumors of the ciliary epithelium [in German] Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Ophthalmol. 1908;68:534–87. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badel AJ, Lagrange F. Carcinome primitif de procès et du corps ciliare. Arch Ophthalmol (Paris) 1892;12:143–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verhoeff FH. A rare tumor arising from the pars ciliaris retinae (terato-neuroma) of a nature hitherto unrecognized, and its relation to the so-called glioma-retinae. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1904;10:351–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grinker RR. Gliomas of the retina including results of studies with silver impregnations. Arch Ophthalmol. 1931;5:920–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey P, Cushing H. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1926. A Classification of Tumors of the Glioma Group on a Histogenetic Basis with a Correlated Study of Progress; pp. 54–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson SR. Medulloepithelioma of the retina. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1962;2:483–506. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broughton WL, Zimmerman LE. A clinicopathologic study of 56 cases of intraocular medulloepithelioma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;85:407–18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmerman LE, Broughton WL. A clinicopathologic and follow up study of fifty-six intraocular medulloepitheliomas. In: Jakobiec FA, editor. Ocular Adenxal Tumors. Birmingham, AL: Aesculapius Publishing; 1978. pp. 181–96. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husain SE, Husain N, Boniuk M, Font RL. Malignant nonteratoid medulloepithelioma of the ciliary body in an adult. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:596–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)94010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shields JA, Eagle RC, Jr, Shields CL, De Potter P. Congenital neoplasms of the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium (medulloepithelioma) Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1998–2006. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sosińska-Mielcarek K, Senkus-Konefka E, Jaskiewicz K, Kordek R, Jassem J. Intraocular malignant teratoid medulloepithelioma in an adult: Clinicopathological case report and review of the literature. Acata Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:259–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vadmal M, Kahn E, Finger P, Teichberg S. Nonteratoid medulloepithelioma of the retina with electron microscopic and immunohistochemical characterization. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1996;16:663–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takei H, Florez L, Moroz K, Bhattacharjee MB. Medulloepithelioma: Two unusual locations. Pathol Int. 2007;57:91–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris AT, Garner A. Medulloepithelioma involving the iris. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975;59:276–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.59.5.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaliki S, Shields CL, Eagle RC, Jr, Vemuganti GK, Almeida A, Manjandavida FP, et al. Ciliary body medulloepithelioma: Analysis of 41 cases. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2552–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canning CR, McCartney AC, Hungerford J. Medulloepithelioma (diktyoma) Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:764–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.10.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrillo R, Streeten BW. Malignant teratoid medulloepithelioma in an adult. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97:695–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020010347012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Floyd BB, Minckler DS, Valentin L. Intraocular medullo--epithelioma in a 79-year-old man. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1088–94. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litriĉin O, Latković Z. Malignant teratoid medulloepitheli--oma in an adult. Ophthalmologica. 1985;191:17–21. doi: 10.1159/000309533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahdjoubi A, Cassoux N, Levy-Gabriel C, Desjardins L, Klos J, Caly M, et al. Adult ocular medulloepithelioma diagnosed by transscleral fine needle aspiration: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:561–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.23694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali MJ, Honavar SG, Vemuganti GK. Ciliary body medulloepithelioma in an adult. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58:266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shields JA, Eagle RC, Shields CL, Singh AD, Robitaille J. Pigmented medulloepithelioma of the ciliary body. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:207–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Font RL, Rishi K. Diffuse retinal involvement in malignant nonteratoid medulloepithelioma of ciliary body in an adult. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1136–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.8.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kivelä T, Summanen P. Possible shared pathogenesis of the retinoinvasive phenotype of malignant medulloepithelioma and malignant melanoma of the ciliary body [letter] Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1066. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.7.1066. author reply 1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Online inheritance in man. DICER1. [Last accessed on 2019 May 03]. Available from: http://omim.org/entry/606241 .

- 28.Cai S, Zhao W, Nie X, Abbas A, Fu L, Bihi S, et al. Multimorbidity and Genetic characteristics of DICER1 Syndrome based on Systematic review. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:355–61. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dehner LP. Pleuropulmonary blastoma is THE pulmonary blastoma of childhood. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1994;11:144e51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Priest JR, Williams GM, Manera R, Jenkinson H, Bründler MA, Davis S, et al. Ciliary body medulloepithelioma: Four cases associated with pleuropulmonary blastoma—A report from the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:1001–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.189779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramasubramanian A, Correa ZM, Augsburger JJ, Sisk RA, Plager DA. Medulloepithelioma in DICER1 syndrome treated with resection. Eye (Lond) 2013;27:896–7. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durieux E, Descotes F, Nguyen AM, Grange JD, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M. Somatic DICER1 gene mutation in sporadic intraocular medulloepithelioma without pleuropulmonary blastoma syndrome. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:783–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahm F, Jakobiec FA, Meyer J, Schrimpf D, Eberhart CG, Hovestadt V, et al. Somatic mutations of DICER1 and KMT2D are frequent in intraocular medulloepitheliomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55:418–27. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minoda K, Hirose Y, Sugano I, Nagao K, Kitahara K. Occurrence of sequential intraocular tumors: Malignant medulloepithelioma subsequent to retinoblastoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1993;37:293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mamalis N, Font RL, Anderson CW, Monson MC, Williams AT. Concurrent benign teratoid medulloepithelioma and pineoblastoma. Ophthalmic Surg. 1992;23:403e8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sansgiri RK, Wilson M, McCarville MB, Helton KJ. Imaging features of medulloepithelioma: Report of four cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43:1344–56. doi: 10.1007/s00247-013-2718-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bianciotto C, Shields CL, Guzman JM, Romanelli-Gobbi M, Mazzuca D, Jr, Green WR, et al. Assessment of anterior segment tumors with ultrasound biomicroscopy versus anterior segment optical coherence tomography in 200 cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma P, Shields CL, Turaka K, Eagle RC, Shields JA. Ciliary body medulloepithelioma with neoplastic cyclitic membrane imaging with fluorescein angiography and ultrasound biomicroscopy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1259–61. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Potter PD, Shields CL, Shields JA, Flanders AE. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in children with intraocular tumors and simulating lesions. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1774–83. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Salam S, Algawi K, Alashari M. Malignant non-teratoid medulloepithelioma of the ciliary body with retinoblastic differentiation: A case report and review of literature. Neuropathology. 2008;28:551–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2008.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kivelä T, Tarkkanen A. Recurrent medulloepithelioma of the ciliary body: Immunohistochemical characteristics. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:1566–75. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)32972-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verdijk RM. On the classification and grading of medulloepithelioma of the eye. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2016;2:190–3. doi: 10.1159/000443963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molloy PT, Yachnis AT, Rorke LB, Dattilo JJ, Needle MN, Millar WS, et al. Central nervous system medulloepithelioma: A series of eight cases including two arising in the pons. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:430–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.3.0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shields CL, Schoenberg E, Kocher K, Shukla SY, Kaliki S, Shields JA. Lesions simulating retinoblastoma (pseudoretinoblastoma) in 604 cases: Results based on age at presentation. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:311–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Augsburger JJ, Oehlschlager U, Manzitti JE. Multinational clinical and pathologic registry of retinoblastoma: Retinoblatoma International Collaborative Study report 2. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995;233:469–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00183426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shields JA, Shields CL, Schwartz RL. Malignant teratoid medulloepithelioma of the ciliary body simulating persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous. AmJ Ophthalmol. 1989;107:296–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cassoux N, Charlotte F, Sastre X, Orbach D, Lehoang P, Desjardins L. Conservative surgical treatment of medulloepithelioma of the ciliary body. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:380–1. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramasubramanian A, Shields CL, Kytasty C, Mahmood Z, Shah SU, Shields JA. Resection of intraocular tumors (partial lamellar sclerouvectomy) in the pediatric age group. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2507–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davidorf FH, Craig E, Birnbaum L, Wakely P., Jr Management of medulloepithelioma of the ciliary body with brachytherapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:841–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ang SM, Dalvin LA, Shields CL, Emrich J, Komarnicky L, Shields JA. Plaque radiotherapy for medulloepithelioma in 6 cases from single centre. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2019;8:30–5. doi: 10.22608/APO.2018257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poon DS, Reich E, Smith VM, Kingston J, Reddy MA, Hungerford JL. Ruthenium-106 plaque brachytherapy in the primary management of ocular medulloepithelioma. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1949–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viswanathan, Mukul D, Qureshi S, Ramadwar M, Arora B, Kane SV. Orbital medulloepitheliomas-with extensive local invasion and metastasis: A series of three cases with review of literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:971–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hellman JB, Harocopos GJ, Lin KC. Successful treatment of metastatic congenital intraocular medulloepithelioma with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, enucleation and superficial parotidectomy. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 201811:124–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2018.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chua J, Muen WJ, Reddy A, Brookes J. The masquerades of a childhood ciliary body medulloepithelioma: A case of chronic uveitis, cataract, and secondary glaucoma. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2012;2012:493493. doi: 10.1155/2012/493493. doi: 10.1155/2012/493493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanavi MR, Soheilian M, Kamrava K, Peyman GA. Medulloepithelioma masquerading as chronic anterior granulomatous uveitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42:474–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chung EM, Smirniotopoulos JG, Specht CS, Schroeder JW, Cube R. From the archives of the AFIP: Pediatric orbit tumors and tumorlike lesions: Nonosseous lesions of the extraocular orbit. Radiographics. 2007;27:1777–99. doi: 10.1148/rg.276075138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vajaranant TS, Mafee MF, Kapur R, Rapoport M, Edward DP. Medulloepithelioma of the ciliary body and optic nerve: Clinicopathologic, CT, and MR imaging features. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2005;15:69–833. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]