Abstract

Introduction

The positive/resected lymph node ratio (LNR) predicts survival in many cancers, but little information is available on its value for patients with N2 NSCLC who receive PORT after resection. We tested the applicability of prognostic scoring models and heat mapping to predict overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) in patients with resected N2 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and postoperative radiotherapy (PORT).

Methods

Our test cohort comprised patients identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database with N2 NSCLC who received resection and PORT in 2000–2014. Prognostic scoring models were developed to predict OS and CSS using Cox regression; heat maps were constructed with corresponding survival probabilities. Recursive partitioning analysis was applied to the SEER data to identify optimal LNR cutoff point. Models and cutoff points were further tested in 183 similar patients treated at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in 2000–2015.

Results

Multivariate analyses revealed that low LNR independently predicted better OS and CSS in patients with resected N2 NSCLC who received PORT.

Conclusions

LNR can be used to predict survival of patients with resected N2 NSCLC followed by PORT. This approach, to our knowledge the first application of heat mapping of positive and negative lymph nodes (LNs), was effective in estimating 3-year, 5-year, and 10-year OS probabilities.

Keywords: lymph node ratio, NSCLC, postoperative radiotherapy, heat map, survival

INTRODUCTION

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for nearly 85% of all cases of lung cancer.1 In patients with node-positive NSCLC, the risk of locoregional recurrence is as high as 20%−40%.2 Evidence is emerging that postoperative radiotherapy (PORT) has favorable effects for patients with N2+ disease,3 even though PORT was found to be detrimental to survival in a meta-analysis of studies conducted about three decades ago.4 However, the benefit of PORT remains controversial for patients with N2 NSCLC, because analyses of relevant randomized controlled trials are still ongoing.5 Further, few reports focused on how to identify patients with N2 NSCLC who might derive the greatest (or least) benefit from PORT in terms of overall survival (OS) or cancer-specific survival (CSS).3

Nodal assessment is one way to evaluate the survival outcome of patients who received PORT.6 The lymph node ratio (LNR), defined as the ratio of positive lymph nodes divided by the total number of lymph nodes examined, has been shown in a few studies to be related to survival outcomes in patients with NSCLC receiving PORT. 3 However, most such studies of LNR were single-institution analyses with small numbers of patients with a variety of cutoff points.3

To fill this gap, we sought to identify the potential significance of LNR in assessing survival outcomes in patients with resected N2 NSCLC who underwent PORT. To do so, we constructed heat maps to provide evaluate detailed linkages of different combinations of numbers of positive and negative LNs. We further sought to develop and externally validate a prognostic scoring model for such patients.

METHODS

Database and Cohort Definition

For the database and cohort definition, see Supplementary Data 1.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were compared by using the χ2 test. Recursive partitioning analysis was used to identify optimal cutoff points for the LNR (see Supplementary Data 2 for further details ).7 A cutoff value of 10 for total number of resected LNs was chosen based on previous publications.8 Simple prognostic scoring systems were developed on the basis of significant factors acquired from the multivariate analysis. The scores were the weighted sums of the factors, in which the weights were defined as the quotient of the corresponding estimated coefficient divided by the smallest χ2 coefficient.9 Heat maps were created to visualize the distribution of numbers of positive and negative LNs with the corresponding survival probabilities obtained from the regression models.10 All statistical tests were two sided.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Clinicopathologic information on the patients in the SEER and validation cohorts is provided in Table 1. In the SEER group, the median patient age was 64 years (range 19–90). Of the total 2,329 patients in the SEER group, 51.4% (1,182) were younger than 65 years and 49.2% (1,147) were ≥65 years. In the validation group, the median patient age was 64 years, and 44.3% (81) were men. The median number of resected positive nodes was 3 (range 1–61) in the SEER group and 3 (range 1–25) in the validation group. Compared with the SEER group, fewer patients in the validation group had poorly differentiated tumors. No differences were observed among any of the other clinicopathologic variables (age, sex, type of surgery, chemotherapy, laterality, histology and tumor stage) between the two groups.

Table 1.

Clinical and tumor characteristics in the training and validation cohorts

| Characteristics | SEER Cohort, No. of Patients (%) | MD Anderson Cohort, No. of Patients (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| <65 | 1,182 (50.8) | 94 (51.4) | 0.873 |

| ≥65 | 1,147 (49.2) | 89 (48.6) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1,164 (50.0) | 81 (44.3) | 0.136 |

| Female | 1,165 (50.0) | 102 (55.7) | |

| Type of surgery | |||

| Lobectomy | 2,086 (89.6) | 162 (88.5) | 0.658 |

| Pneumonectomy | 243 (10.4) | 21 (11.5) | |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | 1,864 (80.0) | 139 (76.0) | 0.186 |

| No | 465 (20.0) | 44 (24.0) | |

| Laterality† | |||

| Left | 1,027 (44.1) | 81 (44.3) | 0.969 |

| Right | 1,301 (55.9) | 102 (55.7) | |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1,661 (71.3) | 127 (69.4) | 0.581 |

| Nonadenocarcinoma | 127 (28.7) | 56 (30.6) | |

| Tumor category†† | |||

| T1–2 | 1,793 (77.0) | 150 (82.0) | 0.390 |

| T3–4 | 468 (20.1) | 33 (18.0) | |

| Grade | |||

| Well/moderately differentiated | 1,062 (45.6) | 103 (56.3) | 0.010 |

| Poorly differentiated | 1,069 (45.9) | 63 (34.4) | |

| Other/unknown | 198 (8.5) | 17 (9.3) | |

| No. of total LNs resected | |||

| <10 | 1,244 (53.4) | 30 (16.4) | <0.001 |

| ≥10 | 1,085 (46.6) | 153 (83.6) | |

Laterality data were available for 2,328 patients in the SEER cohort

Tumor stage data were available for 2,261 patients in the SEER cohort.

Abbreviation: LN, lymph node

LNR Cutoff and Kaplan-Meier Survival Estimates

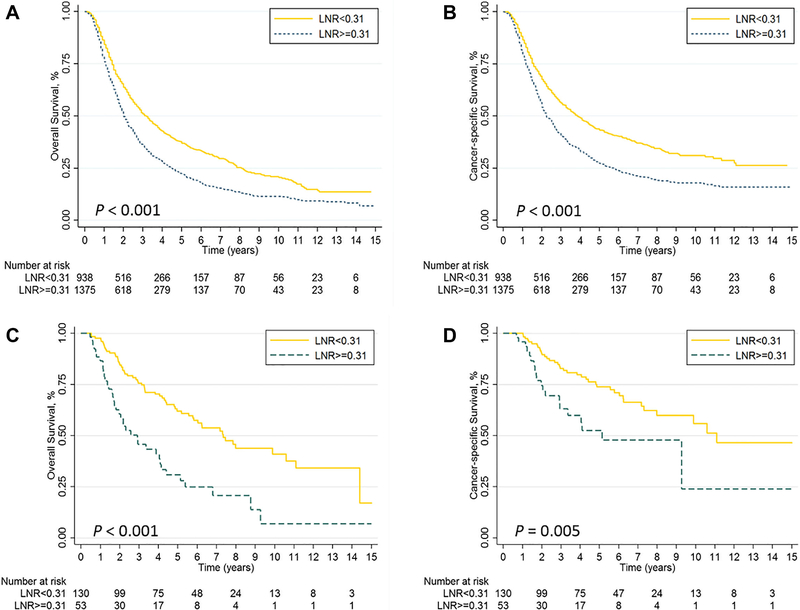

In the training group, the median follow-up time was 23 months and the OS rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 58%, 34%, and 24%. In the validation group, the median follow-up time was 48 months, and the 1, 3, and 5-year OS rates were 78%, 62%, and 48%, respectively. Recursive partitioning analysis identified 0.31 as being the optimal cutoff point for LNR for assessing survival in the training group; patients with LNR <0.31 had better OS and CSS rates than did patients with LNR ≥0.31 in both the training and validation groups (all log-rank P < 0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of (A) overall survival (OS) and (B) cancer-specific survival (CSS) stratified by lymph node ratio (LNR) in the training cohort; (C) OS and (D) CSS stratified by LNR in the validation cohort.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis in the Training Cohort

For OS, all of these factors except for type of surgery and total number of resected LNs retained independent associations with OS in multivariate analysis in the SEER group (Table 2). For CSS, univariate analysis showed age, sex, type of surgery, receipt of chemotherapy, tumor histology and grade, total number of LNs resected, and LNR to be correlated with CSS (Table 3). Age, receipt of chemotherapy, tumor category, tumor grade, and LNR retained independent associations with CSS in multivariate analysis (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors potentially associated with overall survival in SEER patients with N2 NSCLC with nodal resection and postoperative radiation therapy

| Univariate | Chi-square | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | Score | ||

| Age (>65 vs. <65) | <0.001 | 39.549 | 1.38 (1.25–1.53) | <0.001 | 5.1 vs. 0 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.005 | 7.801 | 1.11 (1.00–1.23) | 0.042 | 1.0 vs. 0 |

| Type of surgery | 0.006 | — | |||

| (pneumonectomy vs. lobectomy) | |||||

| Chemotherapy (no vs. yes) | <0.001 | 29.850 | 1.27 (1.13–1.43) | <0.001 | 3.8 vs. 0 |

| Laterality (left vs. right) | 0.836 | — | |||

| Histology (ACC vs. non-ACC) | <0.001 | 14.155 | 1.15 (1.02–1.29) | 0.005 | 1.8 vs. 0 |

| Tumor category (T3–4 vs. T1–2) | <0.001 | 46.467 | 1.49 (1.32–1.68) | <0.001 | 6.0 vs. 0 |

| Grade (poorly vs. well/moderate/other) | 0.005 | 8.005 | 1.16 (1.05–1.29) | 0.004 | 1.0 vs. 0 |

| No. of total LNs resected (≥10 vs. <10) | 0.003 | — | |||

| LNR (≥0.31 vs <0.31) | <0.001 | 55.196 | 1.46 (1.31–1.63) | <0.001 | 7.1 vs. 0 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ACC, adenocarcinoma; LN, lymph node; LNR, lymph node ratio.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors potentially associated with cancer-specific survival for SEER patients with N2 NSCLC who had nodal resection and postoperative radiation therapy

| Univariate | Chi-square | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | Score | ||

| Age (≥65 vs. <65) | <0.001 | 24.102 | 1.33 (1.19–1.49) | <0.001 | 3.9 vs. 0 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 0.025 | - | |||

| Type of surgery (pneumonectomy vs. lobectomy) | 0.012 | - | |||

| Chemotherapy (no vs. yes) | <0.001 | 16.771 | 1.22 (1.07–1.40) | 0.003 | 2.7 vs. 0 |

| Laterality (left vs. right) | 0.270 | - | |||

| Histology (ACC vs. non-ACC) | 0.032 | - | |||

| Tumor category (T3–4 vs. T1–2) | <0.001 | 39.780 | 1.49 (1.30–1.70) | <0.001 | 6.4 vs. 0 |

| Grade (poorly vs. well/moderate/other) | 0.013 | 6.202 | 1.16 (1.04–1.29) | 0.010 | 1.0 vs. 0 |

| No. of total LNs resected (≥10 vs. <10) | 0.022 | - | |||

| LNR (≥0.31 vs <0.31) | <0.001 | 53.220 | 1.51 (1.34–1.71) | <0.001 | 8.6 vs. 0 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ACC, adenocarcinoma; LN, lymph node; LNR, lymph node ratio.

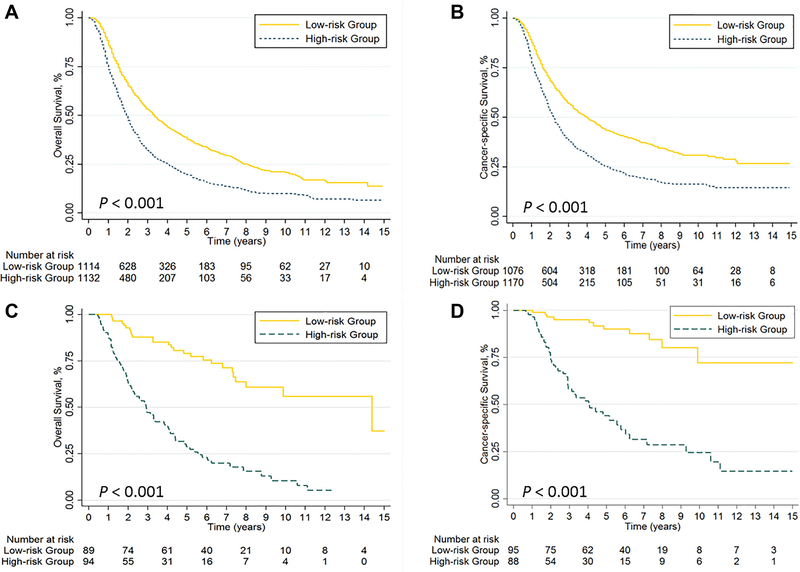

Prognostic Scoring Model

Next, the relative contributions of the variables to the risk scores in the Cox regression models were assessed in terms of their χ2 scores (Tables 2 and 3). For the SEER dataset, using the median value of 9.8 as a cutoff point distinguished two risk groups in terms of OS: low-risk (< 9.8) and high-risk (≥ 9.8). The 1,114 low-risk patients had significantly better OS than did the 1,132 high-risk patients (P < 0.001) (Figure 2A). Use of the same cutoff point for OS in the validation dataset also distinguished the low-risk patients from the high-risk patients (Figure 2C). As for CSS, using a cutoff point of 9.6 (the median χ2 score) led to the whole patient group being classified as either low-risk (< 9.6) or high-risk (≥ 9.6). The CSS was also significantly better in the low-risk group than in the high-risk group (P < 0.001) (Figure 2B). These prognostic scoring models also were able to distinguish the low-risk subgroup from the high-risk subgroup in the validation dataset (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of (A) overall survival (OS) and (B) cancer-specific survival (CSS) in the high-risk vs. low-risk subsets of the training cohort; (C) OS and (D) CSS in the high-risk vs. low-risk subsets of the validation cohort.

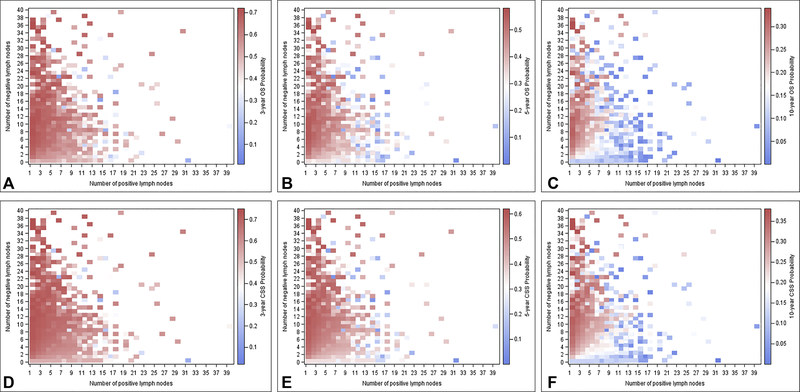

Heat Maps Based on the Survival Models

Heat maps were created to observe the association of combination of positive and negative LNs with survival based on the survival models (Figure 3). Survival probabilities were obtained from the multivariate models. The maps visualize how differences in the positive LN and negative LN counts correlated with 3-year, 5-year, and 10-year survival. Regions in red indicate relatively better survival outcomes compared with regions in blue.

Figure 3.

Heat maps of positive (x axis) and negative (y axis) lymph nodes corresponding to (A) 3-year overall survival (OS), (B) 5-year OS, (C) 10-year OS; and (D) 3-year cancer-specific survival (CSS), (E) 5-year CSS, and (F) 10-year CSS. Red indicates relatively better outcomes than blue.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed prognostic scoring models and corresponding heat maps to predict survival outcomes for patients with resected pN2 NSCLC who also received PORT. In both the training and validation cohorts, patients with low LNR values were more likely to have better survival outcomes. Major American professional societies have published guidelines regarding surveillance for patients after curative surgery for lung cancer.11 Given the acknowledged costs and risks from radiation exposure, our prognostic scoring model has potential clinical implications, in that the model is feasible, easy-to-apply, and may help to identify patients at high risk of poor outcomes.

The LNR is well known for its ability to predict survival in many types of cancer; however, few reports have explored the use of LNR in patients with resected pN2 NSCLC who also received PORT.3 Moreover, until now no easy-to-apply prognostic scoring model had been available to help guide the prognosis. Several clinical scoring systems have been developed that include clinical and laboratory variables for use in predicting cancer survival. Wong et al.12 developed a simple clinical prognostic scoring model for use in predicting the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B carriers; the test set of 1,005 patients and the validation set of 424 patients both showed the feasibility of this approach. Another similar approach was used by Xi et al. to identify patients with esophageal cancer who are likely to benefit from induction chemotherapy before neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; the risk scores derived successfully distinguished patients as low-risk or high-risk.9 In the current study, we created prognostic scoring models with the goal of determining which subgroup of patients would have better survival outcomes among those with resected N2 NSCLC after PORT. For patients with LNR ≥0.31 in clinical practice after surgery, they might have poor outcomes and would need close follow-up while taking into consideration with other clinical significant factors in the prognostic scoring model.

Strengths of this study include the following. First, by using a detailed heat-mapping method, we were able to identify how the number of positive and negative LNs correlated with survival. As Figure 3 illustrates, the segregation in distribution of number positive and negative LNs and survival is easily visualized with this method. Heat maps and the associated analytical methods offer a new way of understanding how LN status correlates with outcomes in patients with NSCLC. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use a heat-map approach to investigate LNs and survival outcomes. Second, this is the first study to explore the efficacy of LNR for predicting survival in patients with NSCLC in which the optimal cutoff point was identified by recursive partitioning. Third, we used an external validation dataset.

The major limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. Also, the SEER database contains no information about chemoradiotherapy, metastatic LN stations, and some other factors that can influence the results from PORT.13,14

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, a low LNR was associated with improved OS and CSS for patients with resected N2 NSCLC who also received PORT. Our innovative use of heat mapping to visualize prognosis based on the number of resected LNs and application of simple prognostic scoring models could facilitate their implementation in routine clinical use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding support: Supported in part by Cancer Center Support (Core) Grant CA016672 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Pechoux C Role of postoperative radiotherapy in resected non-small cell lung cancer: a reassessment based on new data. The oncologist. 2011;16(5):672–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urban D, Bar J, Solomon B, Ball D. Lymph node ratio may predict the benefit of postoperative radiotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2013;8(7):940–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Postoperative radiotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from nine randomised controlled trials. PORT Meta-analysis Trialists Group. Lancet (London, England). 1998;352(9124):257–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdett S, Rydzewska L, Tierney J, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016;10:Cd002142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billiet C, Peeters S, Decaluwe H, Vansteenkiste J, Mebis J, Ruysscher D. Postoperative radiotherapy for lung cancer: Is it worth the controversy? Cancer treatment reviews. 2016;51:10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keles S, Segal MR. Residual-based tree-structured survival analysis. Statistics in medicine. 2002;21(2):313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samayoa AX, Pezzi TA, Pezzi CM, et al. Rationale for a Minimum Number of Lymph Nodes Removed with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Resection: Correlating the Number of Nodes Removed with Survival in 98,970 Patients. Annals of surgical oncology. 2016;23(Suppl 5):1005–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xi M, Liao Z, Deng W, et al. A Prognostic Scoring Model for the Utility of Induction Chemotherapy Prior to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Esophageal Cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2017;12(6):1001–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saraiya P, North C, Duca K. An evaluation of microarray visualization tools for biological insight. Paper presented at: Information Visualization, 2004. INFOVIS 2004. IEEE Symposium on2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang CF, Gould M. Playing the odds: lung cancer surveillance after curative surgery. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2017;23(4):298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong VW, Chan SL, Mo F, et al. Clinical scoring system to predict hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B carriers. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(10):1660–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei S, Xie M, Tian J, Song X, Wu B, Liu L. Propensity score-matching analysis of postoperative radiotherapy for stage IIIA-N2 non-small cell lung cancer using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Radiation oncology (London, England). 2017;12(1):96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billiet C, Decaluwe H, Peeters S, et al. Modern post-operative radiotherapy for stage III nonsmall cell lung cancer may improve local control and survival: a meta-analysis. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2014;110(1):3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.