Abstract

Background.

The epidemiology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp) among US children (<18 years) hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is poorly understood.

Methods.

In the Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community study, we prospectively enrolled 2254 children hospitalized with radiographically confirmed pneumonia from January 2010-June 2012 and tested nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs for Mp using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Clinical and epidemiological features of Mp PCR–positive and –negative children were compared using logistic regression. Macrolide susceptibility was assessed by genotyping isolates.

Results.

One hundred and eighty two (8%) children were Mp PCR-positive (median age, 7 years); 12% required intensive care and 26% had pleural effusion. No in-hospital deaths occurred. Macrolide resistance was found in 4% (6/169) isolates. Of 178 (98%) Mp PCR–positive children tested for copathogens, 50 (28%) had ≥1 copathogen detected. Variables significantly associated with higher odds of Mp detection included age (10–17 years: adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 10.7 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 5.4–21.1] and 5–9 years: aOR, 6.4 [95% CI, 3.4–12.1] vs 2–4 years), outpatient antibiotics ≤5 days preadmission (aOR, 2.3 [95% CI, 1.5–3.5]), and copathogen detection (aOR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.3–3.3]). Clinical characteristics were non-specific.

Conclusions.

Usually considered as a mild respiratory infection, Mp was the most commonly detected bacteria among children aged ≥5 years hospitalized with CAP, one-quarter of whom had codetections. Although associated with clinically nonspecific symptoms, there was a need for intensive care in some cases. Mycoplasma pneumoniae should be included in the differential diagnosis for school-aged children hospitalized with CAP.

Keywords: community, pneumonia, mycoplasma, bacterial disease, children

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a common bacterial pathogen associated with a wide array of clinical manifestations, including upper respiratory infections, pneumonia, and extrapulmonary manifestations (eg, encephalitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome) [1–7]. Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp) is also often associated with community- and facility-based outbreaks, particularly among school-aged children and young adults [8–13]. However, the burden and epidemiology of hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) due to Mp is poorly understood, largely because diagnostic testing has generally employed serology or nonstandardized molecular approaches [14].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study was a prospective, multicenter, active population-based surveillance study of the incidence and etiology of CAP among hospitalized US patients. In the EPIC study, Mp was the most commonly detected bacterial pathogen (8%) among enrolled children (<18 years old), with an estimated annual incidence of 1.4 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–1.6) cases per 10 000 children using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [15]. Using this dataset, we describe the specific epidemiological and clinical features of Mp CAP among hospitalized children.

METHODS

Study Population

The details of the pediatric EPIC study have been published else where [15]. In brief, children (<18 years of age) admitted with clinical and radiographic pneumonia were enrolled from 1 January 2010 through 30 June 2012, at 3 children’s hospitals (Memphis, Tennessee; Nashville, Tennessee; and Salt Lake City, Utah). Final determination of inclusion in the study required independent confirmation by a dedicated board-certified pediatric study radiologist [15]. Radiographic evidence of pneumonia was defined as the presence of consolidation, other infiltrate, or pleural effusion [16].

Children with recent hospitalization, previous enrollment in the EPIC study, residence in an extended-care facility, an alternative respiratory disorder diagnosis, or newborns who never left the hospital were excluded, as were children with a tracheostomy, cystic fibrosis, neutropenia with cancer, recent solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplant, current graft-vs-host disease, or human immunodeficiency virus infection with a CD4 count <200 cells/μL. After written informed consent, patients and/or caregivers were interviewed, and medical charts were abstracted for clinical and epidemiological data. Institutional review boards at each institution and the CDC approved the study protocol.

Specimen Collection and Laboratory Testing

Blood and respiratory specimens were obtained for pathogen testing using multiple modalities as previously described (Supplementary Materials) [16]. In brief, real-time PCR assays were performed at the study sites on combined nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal (NP/OP) swabs [16]. Further Mp confirmatory testing using a multiplex real-time PCR assay was performed at CDC; cultures were performed on Mp PCR-positive specimens [17]. Macrolide susceptibility testing was performed on all corresponding isolates of Mp PCR-positive specimens and/ or extracted nucleic acid by genotyping of the 23S ribosomal RNA gene using a real-time PCR assay with high-resolution melt analysis [18–21]. The Mp research test results were not available to treating clinicians.

Case Definitions

A CAP patient with a positive Mp PCR NP/OP specimen was considered to have Mp CAP (Mp PCR-positive). If Mp was not detected by PCR on a NP/OP specimen, the patient was considered to have CAP without Mp (Mp PCR-negative). A CAP patient was considered to have macrolide-resistant Mp if they had an Mp isolate and/or extracted nucleic acid with positive genotyping for macrolide nonsusceptibility. Codetection was defined as detection of Mp with ≥1 other bacterial or viral pathogen.

We also perfomed a subanalysis comparing Mp PCR-positive pneumonia to typical bacterial CAP (ie, detection of Haemophilus influenzae or other gram-negative bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, or Streptococcus pyogenes in blood, endotracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage specimen, or pleural fluid using culture and/or PCR; Supplementary Materials). If viruses such as such as adenovirus (AdV); corona-viruses; human metapneumovirus (HMPV); human rhinovirus; influenza A/B viruses; parainfluenza virus (PIV) 1, 2, and 3; or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) were detected by PCR of NP/ OP swabs or if serology for AdV, HMPV, influenza A/B, PIV, or RSV showed a 4-fold increase in antibody titer, the patient was considered to have viral CAP (Supplementary Materials).

Antibiotics considered active against Mp included macrolides (eg, erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin), fluoroquinolones (eg, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin), and doxycycline. Any previous outpatient antibiotic exposure was defined as self-reported antibiotic use ≤5 calendar days before admission. Inpatient antibiotic exposure was defined as receipt of an antibiotic at any time after admission.

Statistical Analysis

We compared children hospitalized with CAP with and with-out PCR-positive Mp using descriptive statistics, including the Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests for comparison of categorical variables and median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous data using nonparametric tests, as appropriate. To assess the impact of whether including children without a detected pathogen (n = 395 [19%]) in the Mp PCR-negative group (n = 2072) would impact our findings, a sensitivity analysis was performed; no significant differences were identified and therefore children without a detected pathogen were included in the Mp PCR-negative group.

We performed bivariate analyses comparing children with and without PCR-positive Mp, and also stratified by age; we assessed demographics and clinical features, including illness severity as assessed by intensive care unit (ICU) admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, prolonged length of hospital stay (defined as >90th percentile, ie, ≥6 days), hypoxia, and death. Hypoxia was defined as oxygen saturation rate on admission <92% using pulse oximetry on room air, or use of supplemental oxygen at presentation. For children <5 years old, white blood cell (WBC) count >15 000 cells/μL or <5500 cells/μL, and for children ≥5 years old, WBC count >11 000 cells/μL or <3000 cells/μL, was considered abnormal. We also performed stratified analyses assessing Mp CAP by antibiotic status and type, and codetected pathogens; and made specific comparisons between Mp CAP and CAP due to typical bacterial and respiratory viral pathogens.

We used multivariable logistic regression to assess features independently associated with and without positive Mp PCR; only children who had specimens tested for both bacteria and viruses were included. Variables with a bivariate P value <.20 or with known or hypothesized biological and/or epidemiological plausibility were included in the models. We fitted models using all candidate variables and automated stepwise procedures, and then fitted alternate models using only selected variables. We used Akaike information criterion to help select among alternate models—this statistic simultaneously accounts for goodness of fit and complexity of the tentative models. To resolve collinearity between study site and race in the final model, we controlled for study site and not race. All statistical tests were interpreted in a 2-tailed fashion to estimate P values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Study Population

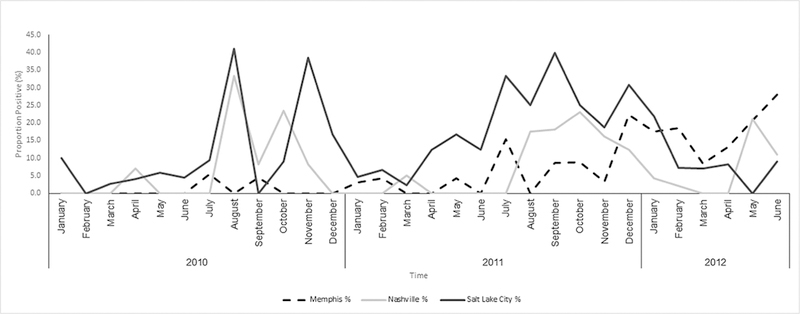

Among 3803 eligible children hospitalized with CAP, 2638 (69%) were enrolled; of these, 2358 (89%) met the criteria of radiographic pneumonia. Of the 2358 children with CAP, 2254 (96%) had Mp PCR tests performed and Mp was detected in 182 (8%). The median age of Mp PCR-positive children was 7 years (IQR, 4.0–11.0 years); 60% were male and 62% were white (Table 1). Mp was more prevalent among children aged 5–9 years (17%) and 10–17 years (24%) compared with children <5 years old (3%; P <.01). The highest prevalence of Mp was in Salt Lake City (11%), followed by Memphis (7%) and Nashville (6%) (Supplementary Table 1). At the Salt Lake City site, Mp was detected throughout the year in 2011, with no clear seasonality (Figure 1). At the other sites, peaks in summer and fall seasons were observed.

Table 1.

Epidemiologic Features Among Children Hospitalized for Community-acquired Pneumonia With and Without Mycoplasma pneumoniae (N = 2254)

| Characteristic |

Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR-Positivea (n = 182) |

Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR-Negativeb (n = 2072) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| <2 | 21 (12) | 988 (48) | Reference | |

| 2–4 | 30 (16) | 544 (26) | 2.6 (1.5–4.6) | <.01 |

| 5–9 | 67 (37) | 336 (16) | 9.4 (5.7–15.6) | <.01 |

| 10–17 | 64 (35) | 204 (10) | 14.8 (8.8–24.7) | <.01 |

| Sex, male | 109 (60) | 1125 (54) | 1.3 (.9–1.7) | .1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 113 (62) | 764 (37) | Reference | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 32 (18) | 744 (36) | 0.3 (.2–.4) | <.01 |

| Hispanic | 29 (16) | 399 (19) | 0.5 (.3–.8) | <.01 |

| Other | 5 (3) | 98 (5) | 0.3 (.1–.7) | <.01 |

| Study sitec | ||||

| Salt Lake City, Utah | 81 (45) | 677 (33) | Reference | |

| Memphis, Tennessee | 60 (43) | 783 (54) | 0.6 (.5–.9) | .01 |

| Nashville, Tennessee | 41 (34) | 612 (48) | 0.6 (.4–.8) | .003 |

| Household size >5 individuals | 61 (33) | 668 (33) | 1.1 (.8–1.4) | .08 |

| Daycare (children <6 y of age) | (n = 61) | (n = 1630) | ||

| Attends daycare | 12 (20) | 543 (33) | 0.5 (.3–.9) | .03 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Radiographically confirmed community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in a patient enrolled in Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study with a positive Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR result.

Radiographically confirmed CAP in a patient enrolled in EPIC with a negative Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR result.

At each study site, there was one children’s hospital.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Mycoplasma pneumoniae among children hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia who underwent real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, by time and study site, January 2010–June 2012. Prevalence = (number of M. pneumoniae PCR-positive nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal [NP/OP] specimens/ total number of NP/OP specimens that underwent PCR testing) × 100.

Bivariate and Stratified Analysis

Clinical Characteristics

The duration of symptoms before hospitalization was longer for Mp PCR-positive children compared with Mp PCR-negative children (median, 6.8 [IQR, 4.6–9.5] days vs 3.6 [IQR, 2.0–5.8] days; P <.01). The differences in clinical manifestations between Mp PCR-positive and Mp PCR-negative children are detailed in Table 2. On chest radiography, Mp PCR-positive children were as likely as Mp PCR-negative children to have consolidation (59% vs 59%; P =.9) and multilobar infiltrates (23% vs 28%; P =.2), but more likely to have pleural effusion (26% vs 12%; P <.01) and hilar lymphadenopathy (10% vs 6%; P =.02). Leukopenia was less common among Mp PCR-positive children than Mp PCR-negative children (1% vs 6%; P =.03).

Table 2.

Clinical Features Among Children Hospitalized for Community-acquired Pneumonia With and Without Mycoplasma pneumoniae (N = 2254)

| Characteristic |

Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR-Positivea (n = 182) |

Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR-Negativeb (n = 2072) |

Unadjusted OR |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentationc | ||||

| Fever/feverish | 174 (96) | 1885 (91) | 2.2 (1.01–4.5) | .03 |

| Cough | 174 (96) | 1960 (95) | 1.2 (.6–2.6) | .6 |

| Fatigue | 142 (78) | 1425 (63) | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | <.01 |

| Lack of appetite | 141 (77) | 1542 (68) | 1.2 (.8–1.7) | .4 |

| Dyspnea | 121 (67) | 1479 (71) | 0.8 (.6–1.1) | .2 |

| Chills | 102 (56) | 729 (35) | 2.3 (1.7–3.2) | <.01 |

| Headache | 87 (48) | 425 (21) | 3.5 (2.6–4.8) | <.01 |

| Sore throat | 86 (47) | 582 (28) | 2.3 (1.7–3.1) | <.01 |

| Wheezing | 82 (45) | 1303 (63) | 0.5 (.4–.7) | <.01 |

| Runny nose | 80 (44) | 1484 (72) | 0.3 (.2–.4) | <.01 |

| Abdominal pain | 76 (42) | 427 (21) | 2.7 (2.0–3.8) | <.01 |

| Diarrhea | 64 (35) | 626 (30) | 1.3 (.9–1.7) | .2 |

| Myalgia | 63 (35) | 366 (18) | 2.5 (1.8–3.4) | <.01 |

| Chest pain | 50 (27) | 436 (21) | 1.4 (1.01–2.0) | .04 |

| Chest retraction | 46 (25) | 953 (46) | 0.4 (.3–.6) | <.01 |

| Underlying condition | ||||

| Any condition (≥1 condition) | 83 (46) | 1066 (51) | 0.8 (.6–1.1) | .1 |

| Asthma/reactive airway disease | 55 (30) | 700 (34) | 0.9 (.6–1.2) | .3 |

| Preterm birthd | 6/21 (29) | 201/988 (20) | 1.6 (.6–4.1) | .4e |

| Congenital heart disease | 14 (8) | 147 (7) | 1.1 (.6–1.9) | .8 |

| Neurological disorder | 11 (6) | 180 (9) | 0.7 (.4–1.3) | .2 |

| Chromosomal disorder | 16 (9) | 112 (5) | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) | .06 |

| Examination findings at presentation | ||||

| Decreased breath sounds | 114 (63) | 842 (41) | 2.4 (1.8–3.3) | <.01 |

| Rales | 110 (60) | 814 (39) | 2.4 (1.7–3.2) | <.01 |

| Tachypneaf | 78 (43) | 740 (36) | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | .05 |

| Documented feverg | 67 (36) | 1003 (48) | 0.6 (.5–.8) | <.01 |

| Hypoxiah | 77 (42) | 768 (37) | 1.3 (.9–1.7) | .2 |

| Chest indrawing | 55 (30) | 1172 (57) | 0.3 (.2–.5) | <.01 |

| Rhonchi | 49 (27) | 855 (41) | 0.5 (.4–.7) | <.01 |

| Wheezing | 48 (26) | 875 (42) | 0.5 (.3–.7) | <.01 |

| Radiographic findingsi | ||||

| Consolidation | 108 (59)j | 1219 (59) | 1.0 (.8–1.4) | .9 |

| Single lobar infiltrate | 59 (32) | 534 (26) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | .05 |

| Multilobar infiltrates | 42 (23) | 573 (28) | 0.8 (.5–1.1) | .2 |

| Multilobar infiltrates (unilateral) | 20 (11) | 155 (7) | 1.5 (.9–2.5) | .09 |

| Multilobar infiltrates (bilateral) | 22 (12) | 420 (20) | 0.5 (.3–.9) | <.01 |

| Pleural effusion | 48 (26) | 244 (12) | 2.7 (1.9–3.8) | <.01 |

| Complicated bronchiolitis | 21 (12) | 610 (29) | 0.3 (.2–.5) | <.01 |

| Hilar lymphadenopathy | 18 (10) | 114 (6) | 1.9 (1.1–3.2) | .02 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| Abnormal WBC countk | ||||

| Leukopenia | 2/160 (1) | 98/1074 (6) | 0.2 (.05–.8) | .03 |

| Leukocytosis | 40/160 (25) | 463/1074 (27) | 0.9 (.6–1.3) | .6 |

| Abnormal platelet countl | ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 6/159 (4) | 73/1681 (4) | 0.9 (.4–2.0) | .7 |

| Thrombocytosis | 15/159 (9) | 182/1681 (11) | 0.9 (.5–1.5) | .6 |

| Hyponatremiam | 12/110 (11) | 125/1352 (9) | 1.2 (.6–2.3) | .6 |

| Severity of illness | ||||

| ICU admission | 21 (12) | 431 (21) | 0.5 (.3–.8) | <.01 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 3 (2) | 143 (7) | 0.2 (.07–.7) | <.01 |

| Length of stay, d, median (IQR) | 2 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | .1n | |

| Antibiotics | ||||

| Receipt of an outpatient antibiotic | 90 (50) | 482 (23) | 3.2 (2.4–4.4) | <.01 |

| Receipt of antibiotics prior to admission within 5 d | 64 (35) | 338 (16) | 2.8 (2.0–3.9) | <.01 |

| Penicillins | 44/64 (69) | 173/338 (51) | Reference | |

| Cephalosporins | 13/64 (20) | 101/338 (30) | 0.5 (.3–1.0) | .05 |

| Macrolides | 7/64 (11) | 56/338 (17) | 0.5 (.2–1.2) | .1 |

| Inpatient antibiotics | 175 (96) | 1794 (87) | 3.9 (1.8–8.3) | <.01 |

| Macrolideso | 75/175 (43) | 351/1794 (20) | 2.3 (1.6–3.3) | <.01 |

| Penicillins | 72/175 (41) | 776/1794 (43) | Reference | |

| Cephalosporin | 27/175 (15) | 639/1794 (36) | 0.5 (.3–.7) | <.01 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; WBC, white blood cell.

Radiographically confirmed community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in a patient enrolled in the Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community (EPIC) study with a positive Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR result.

Radiographically confirmed CAP in a patient enrolled in the EPIC study with a negative Mycoplasma pneumoniae PCR result.

Clinical presentation is based on patient history.

Only for those children <2 years of age.

Fisher exact test.

Tachypnea: For children <2 months: >60 breaths/minute; 2 months to <12 months: >50 breaths/minute; 12 months to 5 years: >40 breaths/minute; >5 years: >25 breaths/minute were considered as abnormal.

Temperature ≥38.0°C or ≥100.4°F.

Hypoxia: Oxygen saturation rate <92% on admission using pulse oximetry on room air or requirement of supplemental oxygen at the time of presentation.

The radiographic findings are not mutually exclusive and could overlap.

Thirty-two (30%) of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae CAP children with a consolidation had a codetection.

For children <5 years old, WBC count >15 000/μL or <5500/μL and for children ≥5 years old, WBC count >11 000/μL or <3000/μL was considered abnormal.

Platelet count of <150 000 cells/μL or >500 000 cells/μL was considered abnormal.

For children <1 year of age, serum sodium <130 U/L and for those >1 year of age, serum levels of <135 U/L were considered abnormal.

Wilcoxon 2-sample test.

Macrolides received as inpatient treatment: azithromycin 74 (99%); clarithromycin: 1 (1%).

Mp PCR-positive children were less likely to require ICU admission (12% vs 21%; P <.01) or invasive mechanical ventilation (2% vs 7%; P <.01) than Mp PCR-negative children (Table 2). Among the 21 (12%) Mp PCR-positive children admitted to the ICU, age ranged from 4 months to 17 years (median, 6 years). Of the 3 children who required invasive mechanical ventilation, the 2 younger children had underlying asthma, radiographic consolidation, and codetections (8-month-old with RSV and rhinovirus and a 3-year-old with rhinovirus); an older child (9 years) had congenital heart disease, a past history of leukemia, alveolar disease on chest radiography, and no codetections.

When comparing children with Mp PCR-positive CAP with CAP due to typical bacterial pathogens, children with typical bacterial pathogens were significantly more likely to be <5 years old (58% vs 20%; P <.01) and less likely to have rales (39% vs 63%; P <.01). Mp PCR-positive children were less likely to have consolidation (56% vs 81%; P < .01), pleural effusion (26% vs 56%; P <.01), or ICU admission (11% vs 36%; P <.01) and had a shorter hospital length of stay (median, 2 days vs 6 days; P <.01) than children with typical bacterial pneumonia (Supplementary Table 3). Compared with children with viral pneumonia, Mp PCR-positive children were significantly more likely to report a headache (48% vs 17%; P <.01) or sore throat (48% vs 26%; P <.01) but less likely to report dyspnea (61% vs 72%; P <.01) or rhinorrhea (3% vs 10%; P = .02). In addition, Mp PCR-positive children were less likely to have wheezing (25% vs 46%; P < .01) and to have ICU admission (11% vs 21%; P < .01) than children with viral pneumonia (Supplementary Table 3).

Antibiotic Treatment

A higher proportion of Mp PCR-positive children received an antibiotic within 5 days before admission compared with Mp PCR-negative children (35% vs 16%; P <.01) (Table 2). When stratified by age, Mp PCR-positive children were more likely to have received outpatient antibiotic treatment than Mp PCR-negative children in both the 5–9 years (39% vs 16%; P <.01) and 10–17 years (44% vs 20%; P <.01) age groups, but were as likely in those <5 years old (19% vs 16%). Among Mp PCR-positive children, there were no significant differences in outcomes (ie, ICU admission or invasive mechanical ventilation) between children who received outpatient antibiotics with and without Mp activity. During hospitalization, among Mp PCR-positive children, length of stay was similar between children who did (median, 3 [IQR, 2–5] days) and did not (median, 2 days [IQR, 1–3] days) receive an inpatient antibiotic with Mp activity (P = .6).

Codetections

Of the 178 (98%) Mp PCR-positive children who had specimens tested for both bacteria and viruses, 50 (28%) had a codetection; 46% of those with a codetection were <5 years old (Supplementary Table 2). Among Mp PCR-positive children, 48 (96%) had at least 1 viral codetection, 1 (2%) had a single bacterial codetection (S. pneumoniae), and 1 (2%) had both bacterial (S. pneumoniae) and viral (rhinovirus) codetections. When stratified by age, Mp PCR-positive children <5 years old were more likely than Mp PCR-negative children to have a codetection (65% vs 34%; P <.01), compared with children 5–9 years old (21% vs 67%; P <.01) and 10–17 years old (21% vs 56%; P <.01), Mp PCR-positive children were less likely than Mp PCR-negative children to have a codetection.

Multivariable Analyses

Variables independently associated with increased odds of Mp detection included age 10–17 years and 5–9 years; clinical signs and symptoms of hilar lymphadenopathy, rales, headache, sore throat, or decreased breath sounds; antibiotic receipt ≤5 days before admission; and any codetection (Table 3). Wheeze, rhinorrhea, and chest pain, in addition to study site and ICU admission, were significantly less likely to be associated with Mp detection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristicsa Associated With Mycoplasma pneumoniae Among US Children (<18 Years) Hospitalized for Community-acquired Pneumonia in Multivariate Analysis

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| 2–4 | Reference group | |

| 5–9 | 6.4 (3.4–12.1) | <.01 |

| 10–17 | 10.7 (5.4–21.1) | <.01 |

| Hilar lymphadenopathy | 3.1 (1.6–5.8) | <.01 |

| Receipt of antibiotics prior to admission within 5 d |

2.3 (1.5–3.5) | <.01 |

| Rales | 2.2 (1.5–3.2) | <0.01 |

| Codetected pathogens | 2.1 (1.4–3.3) | <.01 |

| Headache | 1.6 (1.04–2.5) | .03 |

| Sore throat | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | .03 |

| Decreased breath sounds | 1.5 (1.01–2.2) | .04 |

| Wheezing (symptom) | 0.6 (.4–.9) | <.01 |

| Runny nose | 0.6 (.4–.8) | <.01 |

| Study site (Salt Lake City) | 0.5 (.4–.8) | <.01 |

| Chest pain | 0.4 (.3–.7) | <.01 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

a For this analysis, only children who had specimens tested for both bacteria and viruses were included. Variables that were tested in the model but did not reach significance: sex, clinical presentation of fever/feverish, fatigue, chills, abdominal pain, myalgia, dyspnea, examination findings on presentation: hypoxia, rhonchi, wheezing, chest indrawing, tachypnea, chest retraction; radiographic findings: single and multiple lobar infiltrate, pleural effusion; comorbid condition: chromosomal disorder; household size; interaction between age and codetection.

Macrolide Susceptibility

Of the Mp PCR-positive specimens, 176 (97%) were positive upon repeat PCR testing at the CDC; Mp isolates were recovered from 169 (96%) specimens by culture, and 6 (4%) isolates were macrolide resistant. All 6 (100%) children with macrolide-resistant Mp isolates were non-Hispanic white; 5 (83%) were >5 years old, and 4 (67%) were male. Four (67%) patients with a macrolide-resistant isolate had received a macrolide before admission; 2 between 0 and 5 days before admission and 2 between 6 and 15 days before admission. Of the 6 macrolide-resistant isolates, 3 (50%) were from Memphis, 2 (33%) were from Nashville, and 1 (17%) was from Salt Lake City. There were no significant differences in symptoms and outcomes between children with and without macrolide-resistant Mp.

DISCUSSION

In this large US multicenter active surveillance study with prospective enrollment and systematic microbiological testing among children hospitalized with CAP, Mp was the most commonly detected bacteria and most prevalent in school-aged children ≥5 years old. Although there were no deaths and few patients required mechanical ventilation, 1 in 10 hospitalized children with Mp PCR-positive CAP were admitted to the ICU. Clinically, Mp CAP children had nonspecific symptoms that were not sufficiently distinctive to differentiate CAP due to Mp from other etiologies. The clinical symptoms associated with Mp CAP on multivariable analysis are similar to those observed with respiratory viral illnesses, including influenza infection [22, 23]. In addition, the clinical features independently associated with Mp detection, such as rales, have historically been associated with typical bacterial infections [22].

Respiratory viral PCR panels are increasingly being used for clinical purposes with US Food and Drug Administration-approved and validated assays for Mp. However, their use is not yet widespread [14, 24, 25]. PCR is the current gold standard for diagnosis of Mp, due to its superior specificity compared to serology [17–19, 26–28]. A 2004 US pediatric population-based study reported a Mp prevalence of 14% among 154 children hospitalized with CAP using serology (positive if enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay immunoglobulin M was ≥1:10, or ≥4-fold rise in immunoglobulin G titer) [29]. However, among the 21 children who were seropositive and who had a corresponding NP/OP swab collected within 24 hours of admission, only 12 (57%) had Mp detected by PCR [26]. While Mycoplasma detection in asymptomatic children has been previously reported (21.2% in the Netherlands) [30], Mp was infrequently detected among our convenience sample of asymptomatic controls (0.6%), suggesting that Mp is the likely cause of illness when detected by PCR (Supplementary Materials). The differences in the study results may be a result of differences in control definitions, temporal or geographical variation in Mp activity, or the length of the study (24 months vs 16 months, respectively).

Our results indicate that Mp was the most commonly detected bacteria among children hospitalized with pneumonia and those symptoms, signs, and radiographic findings would not help to distinguish Mp from viral pneumonia; therefore, clinicians may not have a reliable way to suspect Mp infection without diagnostic testing. In our study, results of assays done only for research purposes, including Mp tests, were not available to guide clinical decisions. We did not identify differences in length of stay between Mp patients who did and did not receive an antibiotic with activity against Mp. This finding is also consistent with another study that compared the effectiveness of empirical β-lactam monotherapy vs β-lactam plus macrolide combination therapy using data from the EPIC study; there were no differences in length of stay, rehospitalizations, or recovery at follow-up, including among the subgroup of children with Mp [31]. The EPIC study, however, was observational and limited to hospitalized children. Thus, there is a need for high-quality randomized trials to definitively address the impact of antibiotic therapy with Mp activity on CAP patient outcomes [32].

Macrolide-resistant Mp isolates have been described in the United States (3%−10%) and several other countries, particularly in Europe and Asia [33–35]. We identified very few (6 [4%]) macrolide-resistant Mp isolates and thus were not able to adequately assess factors or outcomes associated with resistance. However, continued vigilance is needed to better understand the extent and clinical implications of macrolide-resistant Mp infections.

Our study has several limitations. By including Mp with codetections, some of the symptoms, especially among those <5 years old, could be attributable to other pathogens. In addition, test sensitivity may be variable between detection assays for some pathogens, especially for bacteria. Another possible limitation is that some patients received antibiotics with Mp activity before NP/OP collection, which may have affected the detection of Mp. However, Mp was detected by PCR in 11% of the children hospitalized with CAP who received an antibiotic with Mp activity before admission [36]. Finally, our findings may not be representative of Mp CAP in the United States, because the 3 study sites were academic centers in urban areas, and 45% of Mp cases were identified at a single site (Salt Lake City, Utah).

In conclusion, Mp was the most commonly detected bacterial pathogen among hospitalized children <18 years old with CAP who underwent NP/OP PCR testing [15]. The prevalence was highest among children 10–17 years old, indicating the significant role of Mp among older children. Although Mp illness is often mild and self-limited [6], in this study 12% of hospitalized children with Mp were admitted to the ICU. Increasing access to Mp PCR could facilitate prompt diagnosis resulting in more targeted and appropriate treatment. In addition, there is a need to understand and define the burden of disease of Mp in the community that is not only causing pneumonia. This can be addressed by systematic surveillance for Mp infection as a cause of CAP and other clinical syndromes, which could further facilitate case and outbreak identification, better characterize the prevalence of macrolide resistance, and inform treatment and infection prevention guidance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the children and families who graciously consented to participate in the Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community study.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Influenza Division of the National Center for Immunizations and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC through cooperative agreements with each study site and was based on a competitive research funding opportunity.

Footnotes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC).

Potential conflicts of interest. K. A. received grant support through his institution from CDC, GlaxoSmithKline, Cubist Pharmaceuticals, and National Institutes of Health for enrollment of patients in other studies. A. T. P. received grant support through his institution from CDC, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Biofire; received royalties from Antimicrobial Therapy. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Bitnun A, Ford-Jones EL, Petric M, et al. Acute childhood encephalitis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32:1674–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daxboeck F, Blacky A, Seidl R, Krause R, Assadian O. Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae childhood encephalitis: systematic review of 58 cases. J Child Neurol 2004; 19:865–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer Sauteur PM, Streuli JC, Iff T, Goetschel P. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated encephalitis in childhood-nervous system disorder during or after a respiratory tract infection. Klin Padiatr 2011; 223:209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer Sauteur PM, Goetschel P, Lautenschlager S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and mucositis—part of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome spectrum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2012; 10:740–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson D, Watkins LK, Demirjian A, et al. Outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Pediatrics 2015; 136:e386–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waites KB, Talkington DF. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004; 17:697–728, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watkins LKF, Olson D, Diaz MH, et al. Epidemiology and molecular characteristics of Mycoplasma pneumoniae during an outbreak of M. pneumoniae-associated Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2017; 36:564–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foy HM, Grayston JT, Kenny GE, Alexander ER, McMahan R. Epidemiology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in families. JAMA 1966; 197:859–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foy HM, Alexander ER. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in childhood. Adv Pediatr 1969; 16:301–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernald GW, Clyde WA Jr. Epidemic pneumonia in university students. J Adolesc Health Care 1989; 10:520–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waites KB. New concepts of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 2003; 36:267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broome CV, LaVenture M, Kaye HS, et al. An explosive outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in a summer camp. Pediatrics 1980; 66:884–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterner G, de Hevesy G, Tunevall G, Wolontis S. Acute respiratory illness with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. An outbreak in a home for children. Acta Paediatr Scand 1966; 55:280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winchell JM. Mycoplasma pneumoniae—a national public health perspective. Curr Pediatr Rev 2013; 9:324–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. ; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community- acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherian T, Mulholland EK, Carlin JB, et al. Standardized interpretation of paediatric chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in epidemiological studies. Bull World Health Organ 2005; 83:353–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz MH, Benitez AJ, Cross KE, et al. Molecular detection and characterization of Mycoplasma pneumoniae among patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015; 2:ofv106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolff BJ, Thacker WL, Schwartz SB, Winchell JM. Detection of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae by real-time PCR and high-resolution melt analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52:3542–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz MH, Benitez AJ, Winchell JM. Investigations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in the United States: trends in molecular typing and macrolide resistance from 2006 to 2013. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53:124–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuoka M, Narita M, Okazaki N, et al. Characterization and molecular analysis of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical isolates obtained in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004; 48:4624–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bébéar C, Pereyre S, Peuchant O. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: susceptibility and resistance to antibiotics. Future Microbiol 2011; 6:423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musher DM, Thorner AR. Community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1619–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harper SA, Bradley JS, Englund JA, et al. ; Expert Panel of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Seasonal influenza in adults and children—diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:1003–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babady NE. The FilmArray respiratory panel: an automated, broadly multiplexed molecular test for the rapid and accurate detection of respiratory pathogens. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2013; 13:779–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratliff AE, Duffy LB, Waites KB. Comparison of the Illumigene Mycoplasma DNA amplification assay and culture for detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:1060–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michelow IC, Olsen K, Lozano J, Duffy LB, McCracken GH, Hardy RD. Diagnostic utility and clinical significance of naso- and oropharyngeal samples used in a PCR assay to diagnose Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42:3339–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beersma MF, Dirven K, van Dam AP, Templeton KE, Claas EC, Goossens H. Evaluation of 12 commercial tests and the complement fixation test for Mycoplasma pneumoniae-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM antibodies, with PCR used as the “gold standard”. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:2277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorigo-Zetsma JW, Zaat SA, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, et al. Comparison of PCR, culture, and serological tests for diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory tract infection in children. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37:14–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michelow IC, Olsen K, Lozano J, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Pediatrics 2004; 113:701–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spuesens EB, Fraaij PL, Visser EG, et al. Carriage of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the upper respiratory tract of symptomatic and asymptomatic children: an observational study. PLoS Med 2013; 10:e1001444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams DJ, Edwards KM, Self WH, et al. Effectiveness of ß-lactam monotherapy vs macrolide combination therapy for children hospitalized with pneumonia. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171:1184–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biondi E, McCulloh R, Alverson B, Klein A, Dixon A, Ralston S. Treatment of mycoplasma pneumonia: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2014; 133:1081–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Atkinson TP, Hagood J, Makris C, Duffy LB, Waites KB. Emerging macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children: detection and characterization of resistant isolates. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28:693–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamada M, Buller R, Bledsoe S, Storch GA. Rising rates of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the central United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012; 31:409–0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Critchley IA, Jones ME, Heinze PD, et al. In vitro activity of levofloxacin against contemporary clinical isolates of Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae from North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 2002; 8:214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris AM, Bramley AM, Jain S, et al. Influence of antibiotics on the detection of bacteria by culture-based and culture-independent diagnostic tests in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4:ofx014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.