Abstract

Background:

Little is known about whether growing awareness of the financial toxicity of cancer diagnosis and treatment has increased clinician engagement or changed current patients’ needs.

Methods:

We surveyed patients with early-stage breast cancer, identified through population-based sampling from two SEER regions, and their physicians. We describe responses from 73% of surgeons (n=370), 61% of medical oncologists (n=306), 67% of radiation oncologists (n=169), and 68% of patients (n=2502).

Results:

Half (50.9%) of responding medical oncologists reported that someone in their practice often or always discusses financial burden with patients, as did 15.6% of surgeons and 43.2% of radiation oncologists. Patients indicated that financial toxicity remains common: 21.5% of whites and 22.5% of Asians had to cut down spending on food, as did 45.2% of blacks and 35.8% of Latinas. Many patients desired to talk to providers about the financial impact of cancer: 15.2% of whites, 31.1% of blacks, 30.3% of Latinas, and 25.4% of Asians. Unmet patient needs for engagement with doctors about financial concerns were common. Of 945 women who worried about finances, 679 (72.8%) indicated that doctors and their staff did not help. Of 523 women who desired to talk to providers about the impact of breast cancer on employment or finances, 283 (55.4%) reported no relevant discussion.

Conclusion:

Many patients report inadequate clinician engagement in management of financial toxicity, even though many providers believe that they make services available. Clinician assessment and communication regarding financial toxicity must improve; cure at the cost of financial ruin is unacceptable.

Keywords: finances, breast cancer, cost, financial toxicity, patient-provider communication

Precis:

Unmet patient needs for engagement with doctors about financial concerns were common in this survey of breast cancer patients, with 73% of 945 women who worried about finances indicating that cancer doctors and their staff did not help. Even physicians who perceive that they are routinely offering necessary services may fail to meet patient needs.

Introduction

Financial toxicity is increasingly recognized as a serious concern for patients with cancer,1, 2 even if they have health insurance.3, 4 Patients with cancer can experience disruptions in employment that affect income5–11 as well as substantial out-of-pocket costs associated with their care, and studies have shown higher rates of bankruptcy filing among patients with cancer.12, 13 Financial burden has also been associated with overall distress, lower health-related quality of life,14, 15 and lower satisfaction with cancer care.16

Little is known about whether growing attention to these issues in the medical literature and popular press has motivated physicians to more routinely embrace practices that address and attempt to mitigate financial toxicity. Furthermore, we know virtually nothing about the level of cancer physicians’ engagement with patients about financial toxicity and patients’ perceptions about unmet need.

To address these issues, we sought to document the relevant self-reported practices of surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists engaged in delivering care to a cohort of patients with breast cancer, who were identified through population-based sampling from two large SEER catchment areas, along with the experiences of their patients. Specifically, we investigated the frequency of these specialists’ reporting that someone in their practice discusses the financial burden of cancer treatments with patients, their awareness of the out-of-pocket costs of the tests and treatments they recommend, how important they perceived it to be to save money for their patients. We further sought to evaluate the financial toxicity experiences of the patients in this modern population-based cohort, by race and ethnicity, including perceptions of the extent to which their oncologists, staff, and other professionals had assisted in addressing the impact of breast cancer on employment or finances, the characteristics of those who express a desire for clinician engagement, and the number who continue to have unmet needs.

Methods

Patient Sample and Data Collection

The iCanCare study identified women aged 20–79 years diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer between January 2013 and September 2015, as reported to the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County, using rapid case ascertainment methods.17 Exclusion criteria included prior breast cancer, stage III-IV disease, or tumors >5cm

After IRB approval, we surveyed patients (median time to survey response 7.7 months) and merged responses with SEER data. We provided a $20 incentive and used a modified Dillman approach to improve response rate. 18 Of 3672 patients surveyed, 2502 (68%) responded.

Physician Sample and Data Collection

Attending surgeons and oncologists were identified primarily through patient report, as well as from information in the SEER database. Most patients identified an attending surgeon (94%) and medical oncologist (81%); 53% identified a radiation oncologist (53%). From the 510 identified surgeons, 504 identified medical oncologists, and 251 identified radiation oncologists, we obtained survey responses from 370 surgeons (73%), 306 medical oncologists (61%), and 169 radiation oncologists (67%).

Measures

Questionnaires were developed using an iterative design process.19 We employed standard techniques to assess content validity. This included review by survey design experts and cognitive interviewing20 with patients and clinicians outside our target sample. Several domains relating to finances were evaluated.

Physician-reported communication and attitudes about financial issues:

Three physician survey measures related to communication and attitudes about patient financial challenges: 1) “How often does someone in your primary practice discuss the financial burden of cancer treatments with your patients?” (never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always); 2) “How aware are you of the out-of-pocket costs of the tests and treatments you recommend?” (not at all, a little, somewhat, quite, or very aware); 3) “When it comes to breast cancer treatment, how important to you is it to save your patients money?” (not at all, a little, somewhat, quite, or extremely).

Patient report of financial toxicity:

Patient survey measures related to financial burdens of the disease and treatment included several independent aspects of this complex construct: 1) lost income since breast cancer diagnosis, 2) out-of-pocket medical expenses related to breast cancer (including co-payments, hospital bills, and medication costs), and 3) out-of-pocket non-medical expenses over and above the normal budget related to breast cancer (e.g., supplies like wigs, bras, or bandages; travel; child/elder care; and complementary or alternative medicine). These were categorized as 0, $1-$500, $501-$2000, $2001-$5000, $5001-$10,000, and >$10,000. In addition, we calculated the proportion of respondents for whom ≥10% of household income was in each of these categories (lost income and out of pocket expenses).

We also asked whether respondents currently had debt (including unpaid bills, credit card balance, bank loans, or borrowing money from family/friends) from breast cancer treatment (yes or no). We inquired whether, due to the financial impact of breast cancer, respondents had to use savings, could not make payments on credit cards or other bills, cut down on spending for food, had utilities turned off because of unpaid bills, or had to move out of their house or apartment because they could not afford to stay there (yes or no).

We evaluated whether patients perceived themselves to be worse off since breast cancer diagnosis in terms of employment status and separately in terms of financial status, and we reported the proportion of these who attributed this at least partly to breast cancer and treatment. We further assessed how much patients worried about current or future financial problems as a result of breast cancer and treatments. Response options for these items were not at all, a little, somewhat, quite a bit, or a lot, and were dichotomized as at least somewhat versus not for analysis.

Patient report of desire for and experiences with clinician engagement:

We inquired how much patients wanted to talk to their health care providers about the impact of having breast cancer on their employment or finances. Response options for these items were not at all, a little, somewhat, quite a bit, or a lot, and were dichotomized as at least somewhat versus less (i.e. a little or not at all) for analysis. We also assessed patient report of engagement with clinicians about financial impact of the disease and treatment. Patients were asked, “During your breast cancer experience, how much did you discuss the impact of having breast cancer on your employment or finances with each of the following people?” Separate items specified “cancer doctors,” “social worker or other professional,” and “primary care doctor.” We further inquired: “How much did your cancer doctors and their staff help you in dealing with the impact of having breast cancer on your employment or finances?” Response options for these items were not at all, a little, somewhat, quite a bit, or a lot.

Patients’ unmet needs related to financial toxicity concerns:

Finally, we developed two measures of unmet need. First, we defined unmet need for communication as having expressed a desire to talk with health care providers about the impact of breast cancer on employment or finances at least somewhat, but having failed to discuss this at least somewhat. Second, we defined unmet need for help with finances as expressing worry about financial problems at least somewhat but indicating that cancer doctors and their staff did not help at least somewhat.

Covariates:

Surveys also ascertained age, race/ethnicity (white, black, Latina, Asian), education (high school or less, some college, ≥college graduate), household income (<$20K, $20 to <$40K, $40K to <$90K, ≥$90K), employment status before diagnosis (full-time, part-time, or not working before diagnosis), insurance status (none, Medicaid, Medicare, private), marital status (married/partnered versus not), and site (Los Angeles, Georgia). Physician characteristics included specialty (medical oncology, surgery, or radiation oncology), annual volume of new breast cancer patients, whether in a teaching practice, and years of experience.

Statistical Analysis

Results from the physician survey were weighted to account for differential nonresponse.21 Results are presented as unweighted number values, with weighted percentages to describe responses regarding physician-reported communication and attitudes.

Results from the patient survey were weighted to account for sampling design and differential nonresponse. To correct for potential bias due to missing data in the patient surveys, values for missing items were imputed using multiple imputation. Results are presented as unweighted, non-imputed number values, with weighted imputed percentages. For the patient-level analyses, we described patient reports of financial toxicity, patient report of clinician engagement, and unmet needs by race/ethnicity. We also constructed a multiple variable regression model to evaluate the correlates of desire for discussion about finances, using theoretically prespecified independent variables: age, race/ethnicity, education, household income, employment status before diagnosis, insurance status, marital status, and site.

Analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Physician Surveys

Of the responding surgeons, 92 (21.3%) were female; 98 (31.6%) of the responding medical oncologists were female; and 46 (26.8%) of the responding radiation oncologists were female. The mean numbers of years in practice were 21.6 (SE = 0.6) for surgeons, 15.7 (SE = 0.7) for medical oncologists, and 17.2 (SE = 0.9) for radiation oncologists. Of the responding surgeons, 110 (28.2%) were in teaching practices, as were 60 (21.0%) of the medical oncologists and 46 (27.1%) of the radiation oncologists. Of the responding surgeons, 109 (24.8%) saw >50 new breast cancer patients in the past year, as did 109 medical oncologists (34.4%) and 93 (53.5%) radiation oncologists (53.5%) [Supplementary Table 1].

As shown in Table 1, many physicians reported engagement and concern regarding costs and financial burden. Of responding medical oncologists, 50.9% reported that someone in their practice often or always discusses the financial burden of cancer with patients,

Table 1:

Self-reported physician practices, knowledge, and attitudes regarding financial toxicity

| Surgeon* | Medical oncologist* | Radiation oncologist* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of discussing financial burden of cancer treatments with patients | |||

| Never | 63 (18.2%) | 10 (3.5%) | 5 (2.8%) |

| Rarely | 133 (36.9%) | 40 (13.5%) | 36 (23.0%) |

| Sometimes | 110 (29.2%) | 94 (32.2%) | 49 (30.0%) |

| Often | 54 (13.8%) | 113 (40.3%) | 48 (31.0%) |

| Always | 7 (1.8%) | 33 (10.6%) | 23 (13.2%) |

| Awareness of out-of-pocket costs of tests and treaments they recommend | |||

| Not at all | 41 (10.5%) | 9 (3.1%) | 7 (3.6%) |

| A little | 100 (26.5%) | 50 (17.3%) | 39 (23.3%) |

| Somewhat | 123 (35.7%) | 111 (39.6%) | 62 (38.8%) |

| Quite | 76 (19.0%) | 89 (30.1%) | 39 (26.1%) |

| Very | 26 (8.3%) | 28 (9.9%) | 15 (8.2%) |

| Importance of saving patients money | |||

| Not at all | 45 (13.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 6 (3.5%) |

| A little | 68 (20.3%) | 35 (11.8%) | 15 (8.4%) |

| Somewhat | 115 (31.1%) | 86 (30.2%) | 53 (32.3%) |

| Quite | 121 (31.6%) | 120 (41.3%) | 63 (40.0%) |

| Extremely | 15 (3.7%) | 45 (15.7%) | 24 (15.8%) |

Unweighted n and weighted percentage

As did 15.6% of surgeons and 43.2% of radiation oncologists. Of the medical oncologists, 40.0% believed themselves to be quite or very aware of the out-of-pocket costs of tests and treatments they recommend, as did 27.3% of surgeons and 34.3% of radiation oncologists. Finally, 57.0% of medical oncologists viewed it to be quite or extremely important to save their patients money, as did 35.3% of surgeons and 55.8% of radiation oncologists.

Patient Surveys

Table 2 shows the diversity of the patient sample, which included 463 blacks, 516 Latinas, and 240 Asians. About a quarter (785, 28.9%) had a high school education or less, and 760 (37.2%) had household income below $40,000 per annum.

Table 2:

Characteristics of responding patients

| Number | Weighted % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <40 | 57 | 2.5 | |

| 40–49 | 305 | 14.2 | |

| 50–59 | 629 | 26.1 | |

| 60–69 | 843 | 36.0 | |

| 70+ | 667 | 21.2 | |

| Missing | 1 | ||

| Race | |||

| White | 1227 | 56.7 | |

| Black | 463 | 17.5 | |

| Latina | 516 | 14.9 | |

| Asian | 240 | 10.9 | |

| Other/unknown/missing | 56 | ||

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 785 | 28.9 | |

| Some college | 720 | 30.2 | |

| College graduate or greater | 922 | 40.9 | |

| Missing | 75 | ||

| Income | |||

| <$20K | 382 | 18.8 | |

| $20K-<$40K | 378 | 18.4 | |

| $40K-<$60K | 329 | 16.0 | |

| $60K-<$90K | 339 | 17.7 | |

| $90K or more | 578 | 29.1 | |

| Don’t know or not reported | 496 | ||

| Employed before diagnosis | |||

| Full time | 931 | 49.5 | |

| Part time | 256 | 11.0 | |

| Not employed | 1015 | 39.5 | |

| Missing | 300 | ||

| Insurance | |||

| None | 110 | 5.3 | |

| Medicaid | 242 | 10.9 | |

| Medicare | 630 | 29.2 | |

| Private | 1196 | 54.6 | |

| Missing | 324 | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Not married or partnered | 961 | 39.1 | |

| Married or partnered | 1496 | 60.9 | |

| Missing | 45 | ||

| Site | |||

| Georgia | 1261 | 49.0 | |

| Los Angeles | 1241 | 51.0 | |

| Surgery | |||

| BCS | 1566 | 65.9 | |

| Mastectomy | 883 | 34.1 | |

| Missing | 43 | ||

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Not initiated by time of survey | 1695 | 73.1 | |

| Yes | 732 | 26.9 | |

| Missing | 75 | ||

| Radiation | |||

| Not initiated by time of survey | 1158 | 46.3 | |

| Yes | 1284 | 53.8 | |

| Missing | 60 |

As shown in Table 3, all measures of patient-reported financial toxicity varied significantly by race/ethnicity (p<0.01). Many women reported debt from treatment, including 27.1% of whites, 58.9% of blacks, 33.5% of Latinas, and 28.8% of Asians. Many patients also had substantial lost income and out-of-pocket expenses that they attributed to breast cancer. Overall, 14% of patients reported lost income that was ≥10% of their household income, 17% of patients reported spending ≥10% of household income on out-of-pocket medical expenses, and 7% of patients reported spending ≥10% of household income on out-of-pocket nonmedical expenses (not shown in table).

Table 3:

Patient-reported financial toxicity and clinician engagement by race/ethnicity

| Characteristic | Weighted %* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n=1227) | Black (n=463) | Latina (n=516) | Asian (n=240) | ||

| Lost income | |||||

| 0 | 73.8 | 62.9 | 58.4 | 59.6 | |

| $1-$500 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 2.9 | |

| $501-$2000 | 6.1 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 9.3 | |

| $2001-$5000 | 5.4 | 10.9 | 10.2 | 10.8 | |

| $5001-$10,000 | 5.6 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 8.6 | |

| >$10,000 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 8.9 | 8.8 | |

| Out of pocket medical expenses | |||||

| 0 | 11.7 | 12.7 | 28.9 | 15.0 | |

| $1-$500 | 23.6 | 28.1 | 27.0 | 28.9 | |

| $501-$2000 | 19.4 | 26.3 | 18.3 | 21.7 | |

| $2001-$5000 | 23.9 | 17.8 | 15.7 | 18.1 | |

| $5001-$10,000 | 16.3 | 12.0 | 7.5 | 12.3 | |

| >$10,000 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 4.0 | |

| Out of pocket non-medical expenses | |||||

| 0 | 24.3 | 19.5 | 29.9 | 16.7 | |

| $1-$500 | 46.0 | 45.6 | 38.4 | 43.0 | |

| $501-$2000 | 19.1 | 21.7 | 21.2 | 23.1 | |

| $2001-$5000 | 7.6 | 8.9 | 7.4 | 10.3 | |

| $5001-$10,000 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 5.0 | |

| >$10,000 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 1.9 | |

| Current debt from treatment | 27.1 | 58.9 | 33.5 | 28.8 | |

| Had to use savings | 35.6 | 52.3 | 46.8 | 43.8 | |

| Could not make payments on bills | 11.6 | 32.1 | 19.3 | 9.0 | |

| Cut down spending on food | 21.5 | 45.2 | 35.8 | 22.5 | |

| Utilities turned off for unpaid bills | 1.7 | 5.9 | 3.2 | 0.5 | |

| Lost home | 1.4 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 1.0 | |

| Employment status worse off at least partly due to breast cancer | 13.2 | 23.5 | 28.5 | 15.2 | |

| Financial status worse off at least partly due to breast cancer | 37.3 | 54.7 | 48.8 | 34.8 | |

| Worry about finances | |||||

| Characteristic | Weighted %* | ||||

| White (n=1227) | Black (n=463) | Latina (n=516) | Asian (n=240) | ||

| Not at all | 41.4 | 29.2 | 26.2 | 34.6 | |

| A little | 26.7 | 21.9 | 24.1 | 30.2 | |

| Somewhat | 15.2 | 18.0 | 21.2 | 14.4 | |

| Quite a Bit | 9.7 | 17.0 | 15.2 | 8.1 | |

| A lot | 7.0 | 13.9 | 13.3 | 12.7 | |

| Desire to talk to healthcare providers about impact of breast cancer on employment or finances | |||||

| Not at all | 72.2 | 55.7 | 55.7 | 57.1 | |

| A little | 12.7 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 17.4 | |

| Somewhat | 8.0 | 13.9 | 12.6 | 13.0 | |

| Quite a Bit | 4.3 | 9.9 | 12.1 | 5.9 | |

| A lot | 2.8 | 7.3 | 5.6 | 6.5 | |

| Discussed impact of breast cancer on employment or finances with cancer doctors | |||||

| Not at all | 75.0 | 66.6 | 66.7 | 66.6 | |

| A little | 14.5 | 15.2 | 10.4 | 17.9 | |

| Somewhat | 6.0 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 9.1 | |

| Quite a Bit | 2.4 | 4.4 | 8.3 | 2.8 | |

| A lot | 2.1 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 3.6 | |

| Discussed impact of breast cancer on employment or finances with social worker or other professional | |||||

| Not at all | 84.9 | 70.8 | 73.9 | 77.3 | |

| A little | 7.4 | 9.6 | 8.6 | 7.9 | |

| Somewhat | 3.6 | 9.0 | 7.0 | 6.7 | |

| Quite a Bit | 2.5 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 3.8 | |

| A lot | 1.7 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 4.4 | |

| Discussed impact of breast cancer on employment or finances with primary care doctor | |||||

| Not at all | 89.2 | 78.6 | 74.8 | 77.4 | |

| A little | 5.3 | 9.4 | 7.2 | 12.0 | |

| Somewhat | 3.2 | 6.9 | 7.2 | 6.0 | |

| Quite a Bit | 1.1 | 2.2 | 5.5 | 1.9 | |

| A lot | 1.1 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 2.7 | |

All comparisons are significant (p<0.01) in Chi-square tests.

Privations attributed to breast cancer varied by race/ethnicity. Few whites (1.4%) or Asians (1.0%) lost their home, but 4.7% of blacks and 6.0% of Latinas did. Similarly, although only 1.7% of whites and 0.5% of Asians had utilities turned off for unpaid bills, 5.9% of blacks and 3.2% of Latinas did. One in five whites (21.5%) and Asians (22.5%) cut down spending on food, as did nearly half of blacks (45.2%), and over a third of Latinas (35.8%). Many women were at least somewhat worried about finances as a result of breast cancer or its treatment: 31.9% of whites, 48.9% of blacks, 49.7% of Latinas, and 35.2% of Asians.

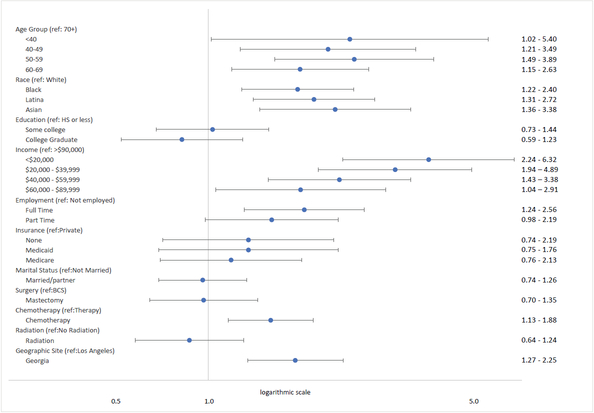

A substantial minority expressed desiring, at least somewhat, to talk to healthcare providers about the impact of breast cancer on their employment or finances, and this was more common among non-whites: 15.2% of whites, 31.1% of blacks, 30.3% of Latinas, and 25.4% of Asians. On multivariable analysis, as shown in Figure 1 (and detailed in Supplementary Table 2), the following characteristics were independently associated with desire for a discussion with healthcare providers about the impact of breast cancer on their employment or finances: younger age, non-white race, lower income, being employed (full time or part time), receiving chemotherapy, and Georgia residency.

Figure 1: Factors Associated with Need for Communication About the Financial Impact of Breast Cancer.

Odds Ratios and 95% confidence intervals from a multivariable logistic regression.

Estimates are from a multiple variable regression model that evaluated the correlates of patients’ self-reported desire to talk to health care providers about the impact of having breast cancer on employment or finances (model more fully detailed in data supplement, online-only). From 2502 patients diagnosed with breast cancer in the iCanCare study.

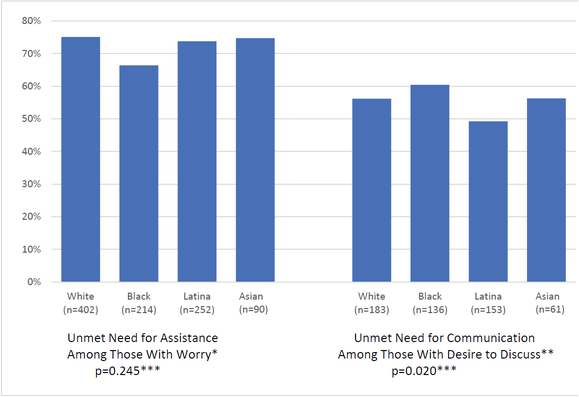

Unmet patient needs for engagement with doctors about financial concerns were common. Of the 945 women who expressed worrying at least somewhat, 679 (72.8%) indicated that cancer doctors and their staff did not help at least somewhat. Of the 523 women who expressed a desire to talk to healthcare providers about the impact of breast cancer on employment or finances, 283 (55.4%) reported that they had not had a relevant discussion with their cancer doctors, primary care providers, social workers, or other professionals. Figure 2 shows, by race/ethnicity, the proportion of patients with unmet needs for communication among those with desire to discuss and the proportion with unmet needs for assistance among those with worry.

Figure 2: Unmet Need For Assistance and Communication Regarding Finances.

* Percentage of patients who reported receiving little or no help from their doctors and staff in dealing with the financial impact of cancer, among those who expressed somewhat or greater worry about financial problems. P value from Pearson χ2 test.

** Percentage of patients who reported little or no discussion of the financial impact of cancer, among those who expressed somewhat or greater desire to talk with health care providers about financial issues.

*** P values from Pearson χ2 test.

Discussion:

In this recent, population-based sample of breast cancer patients diagnosed in two large SEER catchment areas of the United States and surveyed less than one year after diagnosis, financial toxicity and desire for clinician engagement were already substantial and varied by race/ethnicity, with vulnerable groups including the young and those who receive chemotherapy. Although many physicians, particularly medical oncologists, report attempting within their practices to help manage financial issues with their patients, marked unmet need remains. Over two-thirds of patients who were worried about finances as a result of breast cancer or its treatment reported that their cancer doctors and staff did not help substantially. Moreover, over half of those who expressed a desire to discuss the impact of breast cancer on employment or finances reported that they had not had such a discussion.

The privations observed in this study are sobering and consistent with studies prior to the widespread awareness of the potential for financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis and treatment. In a similar population-based sample of patients with breast cancer diagnosed a decade ago, our own group demonstrated concerning rates of serious privations during survivorship, such as economically motivated treatment non-adherence or loss of one’s home.22 However, with growing awareness of financial toxicity and attempts to mitigate it by providers, we had hoped that these experiences would be rare in a more modern sample surveyed relatively soon after diagnosis. Disappointingly, we observed that one in twenty black or Latina patients had already lost their home due to breast cancer diagnosis or treatment. Nearly one in five whites and Asians had to cut down spending on food, and nearly half of blacks and over a third of Latinas reported this privation.

This study also offers important insights about the extent to which the medical community has begun to attempt to address these major concerns. An intriguing analyses of videotaped interactions between African American patients and oncologists at two urban cancer hospitals suggested that cost discussions occur in 45% of clinical interactions.23 The current study builds on these findings and suggests that certain providers (medical oncologists) are more likely to have someone in their practice who routinely addresses these issues. Unfortunately, unmet needs for discussion persist, as does unresolved worry. The proportion of patients who perceive meaningful clinician engagement is low, with far fewer than a quarter of respondents reporting more than a little discussion of these issues—and this is strikingly lower than the proportion of providers (over half of medical oncologists) who perceive routinely making services available.

Given these findings, it is clear that thoughtfully designed, prospective interventions are necessary to address the remarkably common experiences of financial burden that patients report even in the modern era. These interventions might include training for physicians and their staff regarding how to have effective conversations in this context, in ways that are sensitive to cultural differences and needs. Other promising approaches might include the use of advanced technology to engage patients in interactive exercises that elicit their financial concerns and experiences and alert providers to their needs. Scholars have already developed useful tools for the rigorous evaluation of financial experiences that are ideally suited as endpoints in studies that seek improvement of financial burden.24

Although this study has considerable strengths, including its large, population-based sample, its evaluation of a number of both objective and subjective measures of financial burden, and its inclusion of both physicians and the patients they serve, it also has limitations. All data regarding finances derive from self-report, but measures were developed in accordance with principles of rigorous survey design and demonstrate strong face and internal validity. Not all sampled patients or physicians responded to our surveys, and this may introduce bias, but the rates of response were substantial and considerably higher than in most other patient and physician studies. Not all patients saw all types of providers (particularly radiation oncology), but the vast majority did see both surgeons and medical oncologists. We were unable to conduct linked multilevel analyses due to the biases that would be introduced by the different provider mix of each patient. Finally, the study was based in two regions; although these are large catchment areas, experiences in other regions of the United States might differ, and the results should not be extrapolated to other countries, where costs, healthcare systems and coverage of care, policies, and culture differ markedly in ways that likely affect financial experiences and outcomes.

Implications:

For many women, a breast cancer diagnosis no longer causes the physical devastation that it once did. Advances in early detection and less extensive surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy have transformed a disease that once left patients disfigured at best—and at worst took their lives after terrible morbidity. Although progress in breast cancer treatment is laudable, this study demonstrates that we have gone only part of the way to our goal. Efforts must now turn to confront the financial devastation that many patients face, particularly as they progress into survivorship. The first steps for clinical practice and policy are clear: all physicians must assess patients for financial toxicity and learn how to communicate effectively about it. To cure a patient’s disease at the cost of financial ruin falls short of the physician’s duty to serve – and failure to recognize and mitigate a patient’s financial distress is no longer acceptable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the work of our project staff (Mackenzie Crawford, M.P.H. and Kiyana Perrino, M.P.H. from the Georgia Cancer Registry; Jennifer Zelaya, Pamela Lee, Maria Gaeta, Virginia Parker, B.A. and Renee Bickerstaff-Magee from USC; Rebecca Morrison, M.P.H., Alexandra Jeanpierre, M.P.H., Stefanie Goodell, B.S., Irina Bondarenko, M.S., and Rose Juhasz, Ph.D. from the University of Michigan). We acknowledge with gratitude our survey respondents.

Funding:

Funded by grant P01CA163233 to the University of Michigan from the National Cancer Institute and supported by the University of Michigan Cancer Center Biostatistics, Analytics and Bioinformatics shared resource (P30CA46592). Cancer incidence data collection was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003862–04/DP003862; the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute. Cancer incidence data collection in Georgia was supported by contract HHSN261201300015I, Task Order HHSN26100006 from the NCI and cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003875–04-00 from the CDC.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

none

REFERENCES

- 1.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, Provenzale D. Population-Based Assessment of Cancer Survivors’ Financial Burden and Quality of Life: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Oncology Practice 2015;11(2): 145–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2017;109(2): djw205–djw05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC Jr GPG, et al. Financial Hardship Associated With Cancer in the United States: Findings From a Population-Based Sample of Adult Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(3): 259–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The Financial Toxicity of Cancer Treatment: A Pilot Study Assessing Out-of-Pocket Expenses and the Insured Cancer Patient’s Experience. The Oncologist 2013;18(4): 381–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in job loss for women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2011;5(1): 102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. The impact of sociodemographic, treatment, and work support on missed work after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010;119(1): 213–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jagsi R, Hawley ST, Abrahamse P, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on long-term employment of survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Cancer 2014;120(12): 1854–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley CJ, Oberst K, Schenk M. Absenteeism from work: the experience of employed breast and prostate cancer patients in the months following diagnosis. Psychooncology 2006;15(8): 739–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer AG, Taskila T, Ojajarvi A, van Dijk FJ, Verbeek JH. Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA 2009;301(7): 753–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassett MJ, O’Malley AJ, Keating NL. Factors influencing changes in employment among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer 2009;115(12): 2775–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blinder V, Patil S, Eberle C, Griggs J, Maly RC. Early predictors of not returning to work in low-income breast cancer survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;140(2): 407–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State Cancer Patients Found To Be At Greater Risk For Bankruptcy Than People Without A Cancer Diagnosis. Health Affairs 2013;32(6): 1143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meeker CR, Geynisman DM, Egleston BL, et al. Relationships Among Financial Distress, Emotional Distress, and Overall Distress in Insured Patients With Cancer. Journal of Oncology Practice 2016;12(7): e755–e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer 2016;122(8): 283–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of Financial Burden of Cancer on Survivors’ Quality of Life. Journal of Oncology Practice 2014;10(5): 332–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chino F, Peppercorn J, Taylor DH, et al. Self-Reported Financial Burden and Satisfaction With Care Among Patients With Cancer. The Oncologist 2014;19(4): 414–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearson ML, Ganz PA, McGuigan K, Malin JR, Adams J, Kahn KL. The Case Identification Challenge in Measuring Quality of Cancer Care. J Clin Oncol 2002;20(21): 4353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dillman D, Smyth J, Christian L. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method (3rd ed). Hoboken, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowler FJ Jr., Levin CA, Sepucha KR. Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(4): 699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM, Singer E, Tourangeau R. Survey Methodology. 2nd ed Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol 2014;32(12): 1269–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamel LM, Penner LA, Eggly S, et al. Do Patients and Oncologists Discuss the Cost of Cancer Treatment? An Observational Study of Clinical Interactions Between African American Patients and Their Oncologists. Journal of Oncology Practice 2017;13(3): e249–e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 2017;123(3): 476–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.