Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a degenerative brain disease that affects millions of people around the world. As populations in the United States and worldwide age, the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease will only increase. In turn, the social and financial costs of AD will create a difficult environment for many families and caregivers across the globe. By combining genetic information, brain scans, and clinical data, gathered over time through the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), we propose a new Joint High-Order Multi-Modal Multi-Task Feature Learning method to predict the cognitive performance and diagnosis of patients with and without AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Multi-modal, Longitudinal, Tensor

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by the progressive loss of memory and cognitive functions. The Alzheimer’s Association recently released a report [1] in which they described various societal costs of AD in the United States. They found that in 2017 the total spending of caring for individuals with AD surpassed $259 billion. In addition, they report that 1 in 10 people aged 65 or older suffer from some form of Alzheimer’s dementia. Given the widespread effects of AD on patients, their families, and caregivers, it is important that the scientific community investigates methods that can accurately predict the progression of AD.

Following the body of work done through the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), we present a new joint regression and classification model, inspired by our previous works [13,14], that has shown great performance in the identification of relevant genetic and phenotypic biomarkers in patients with AD. Our newly proposed method consists of three major components as follows. First, we use the ℓ2,1-norm regularization [5] to effectively associate input features overtime and generate a sparse solution. Second, we utilize a new group ℓ1-norm regularization proposed in our previous works [10–12,14] to globally associate the weights of the input imaging and genetic modalities, where a modality indicates a single data grouping (e.g. brain imaging data, genetic data, diagnostic data, etc.). The group ℓ1-norm regularization is able to determine which input modality is most effective at predicting a particular output. Third, we incorporate the trace norm regularization [2,4,15,16] to determine relationships that occur within modalities.

2. Joint Multi-modal Regression and Classification for Longitudinal Feature Learning

Joint multi-task learning (e.g. performing regression and classification at the same time) can help discover more robust patterns than those discovered when the tasks are performed using separate objectives [13,14]. These robust patterns can arise when the learned parameters for the regression task become outliers for the classification task.

In the ADNI data set, a collection of input modalities (e.g. VBM, FreeSurfer, SNP) have been collected from patients in every six months. The input imaging features are represented by a set of matrices . The stacked matrices in correspond to measurements recorded at T consecutive time points. Each matrix is composed of k input modalities where Xt = [X11, X12, … , X1k]. Each input modality Xtj consist of dj features such that . is a tensor with D imaging features, n samples, and T time points.

In addition to the input modalities, the ADNI also collected cognitive information from each patient. The output of our model, a prediction of cognitive diagnoses and scores, is represented by the tensor where at each time point t from (1 ≤ t ≤ T) a matrix Yt = [Ytr Ytc] represents the horizontal concatenation of the clinical diagnoses (classification tasks) and cognitive scores (regression tasks) of each patient who participated in the ADNI study.

In order to associate the longitudinal imaging markers and the genetic markers to predict cognitive scores and diagnoses over time, we introduce a tensor implementation of the widely used ℓ2,1-norm:

| (1) |

where denotes the i-th row of the coefficient matrix Wt at time t. Here we define as the unfolding operation of along the n-th mode. Given this definition, it follows that . The ℓ2,1-norm regularization in Eq. (1) will ensure that each feature will either have small, or large values, over the longitudinal dimension.

In heterogeneous feature fusion, the features of a specific input modality can be more discriminative than others for a given task. For example, the features associated with the brain imaging modality may be more useful in determining cognitive scores than the corresponding genetic modality. Conversely, the genetic modality may be more discriminative in predicting a disease diagnosis. To incorporate this global relationship between modalities we use the group ℓ1-norm (G1-norm) proposed in our previous works [10,11,14]:

| (2) |

where k is the number of input modalities.

The regularizations defined above in Eqs. (1–2) couple the learning tasks over time and learn the relative significance of each input modality for a given task. We know, as AD develops, that many cognitive measures are related to one another. This kind of correlation, when combined with a multivariate regression model and the hinge loss from a support vector machine (SVM) classifier, can be modeled by minimizing the rank of the unfolded coefficient matrix in the following objective:

| (3) |

where ∥M∥* = Tr(MMT)1/2 denotes the trace norm of the matrix , which has been shown as the best convex approximation of the rank-norm [2]. The rank minimization will develop joint correlations across each of the learning tasks at different time points. We call J2 in Eq. (3) the Joint High-Order Multi-Modal Multi-Task Feature Learning model. We will use this newly proposed model to effectively predict the cognitive scores and diagnoses of AD patients.

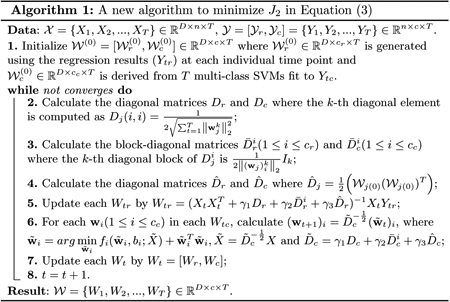

The algorithm to solve the proposed objective in Eq. (3) is summarized in Algorithm 1. Due to the space limit, the derivation of this algorithm and the rigorous proof of its global convergence will be supplied in an extended journal version of this paper.

3. Experiments

In this section, we will evaluate the proposed method on the data set provided by the ADNI. The goal of our experiments is to determine the relationships between the brain imaging data (FreeSurfer and VBM), genotypes encoded by SNPs, and the corresponding cognitive scores and AD diagnoses.

We downloaded 1.5 T MRI scans, SNP genotypes, and demographic information for 821 ADNI-1 participants. We performed voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and FreeSurfer automated parcellation on the MRI data by following [6], and extracted mean modulated gray matter (GM) measures for 90 target regions of interest (ROIs). We followed the SNP quality control steps discussed in [8]. We also downloaded the longitudinal scores of the participants’ Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) and their clinical diagnoses in three categories: healthy control (HC), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and AD. The details of these cognitive assessments can be found in the ADNI procedure manuals. The time points examined in this study for both imaging markers and cognitive assessments included baseline (BL), Month 6 (M6), Month 12 (M12) and Month 24 (M24). All the participants with no missing BL/M6/M12/M24 MRI measurements, SNP genotypes, and cognitive measures were included in this study; this resulted in a set of 412 subjects with 155 HC, 110 MCI, and 147 AD.

3.1. Joint Regression and Classification Performance

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of our new Joint High-Order Multi-Modal Multi-Task Feature Learning method, we tested its regression and classification performance against an array of popular machine learning models. In each experiment, we fine tune the parameters of our model (γ1, γ2 and γ3) by searching a grid of powers of 10 between 10−5 to 105. The experiments are performed using a classical 5-fold cross-validation strategy for each of the chosen algorithms.

Results.

In Table 1 we can see that our proposed algorithm performs significantly better than a collection of “out-of-the-box” machine learning methods. The significant performance improvements in both regression and classification are due to the fact that our algorithm is the only one capable of incorporating the important longitudinal information into its prediction. The various regularizations (ℓ2,1-, group ℓ1- and trace norms) that we apply to the unfolded matrix ensure that our proposed algorithm is able to incorporate the longitudinal patterns that are intrinsic to many clinical studies (including the ADNI).

Table 1.

Regression: Root mean squared error (RMSE) results of the proposed algorithm compared to linear regression, ridge regression, Lasso regression, K-nearest neighbors (KNN), and a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) classifier. Classification: F1 scores of classifying HC, MCI, and AD patients of the proposed algorithm compared to logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine (SVM) (with RBF kernel), K-nearest-neighbors (KNN), and a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) regressor.

| Regression Performance (RAVLT) | |||

| Linear | Ridge | Lasso | |

| RMSE | 1.41e+13±1.19e+12 | 0.333±0.016 | 0.333±0.016 |

| KNN | MLP | Ours | |

| RMSE | 0.344±0.009 | 0.318±0.026 | 0.284±0.011 |

| Classification Performance (Diagnosis) | |||

| Logistic | RandomForest | SVM | |

| F1 (HC) | 0.472±0.054 | 0.434±0.048 | 0.310±0.073 |

| F1 (MCI) | 0.420±0.065 | 0.448±0.045 | 0.460±0.071 |

| F1 (AD) | 0.456±0.044 | 0.494±0.098 | 0.450±0.088 |

| KNN | MLP | Ours | |

| F1 (HC) | 0.340±0.069 | 0.424±0.089 | 0.560±0.034 |

| F1 (MCI) | 0.396±0.054 | 0.386±0.092 | 0.508±0.039 |

| F1 (AD) | 0.354±0.093 | 0.444±0.039 | 0.644±0.120 |

3.2. Identification of Longitudinal Imaging Biomarkers

FreeSurfer.

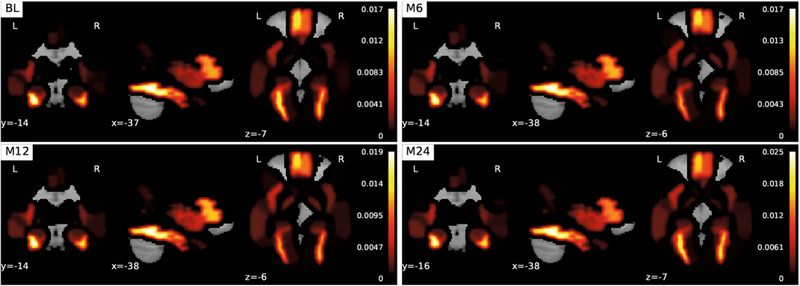

The coefficients associated with the FreeSurfer modality in are extracted from at each time point (BL, M6, M12, M24). Each corresponding coefficient is mapped onto Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) [9] regions of the brain (Fig. 1). When we look at the FreeSurfer brain heatmap we can draw a few interesting conclusions. First, the images show the same sparse image representation over time. This observation shows us that that the ℓ2,1-norm is working as expected and is successfully associating features across time, which illustrates the longitudinal predictive potential (a clinically important distinction) of our method. Second, we see that multiple parts of the brain related to the frontal gyrus have high weights compared to other parts of the brain not connected to AD, which is nicely consistent with existing clinical findings [3].

Fig. 1.

Visualization of the FreeSurfer modality coefficients derived from at various times (BL/M6/M12/M24). The top ten AAL regions are as follows (largest to smallest): Fusiform_L, Fusiform_R, Frontal_Med_Orb_L, Frontal_Inf_Tri_L, Frontal_Med_Orb_R, Frontal_Inf_Tri_R, ParaHippocampal_L, Insula_L, Pallidum_R, and Pallidum_L.

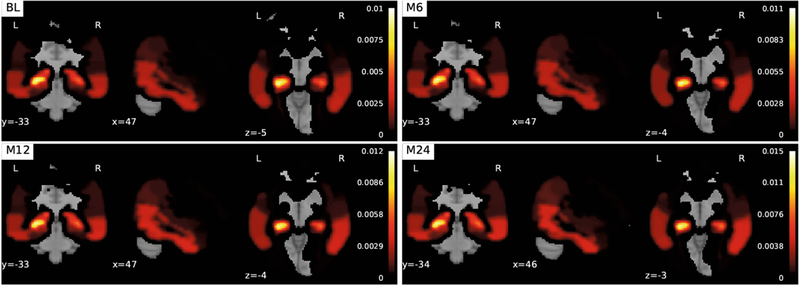

Voxel-Based Morphometry.

The coefficients associated with the VBM modality in are extracted from the coefficient matrix at each time point. Each coefficient weight is mapped onto AAL regions of the brain (Fig. 2). The images associated with the VBM modality share the same longitudinal sparsity that we observed in the FreeSurfer coefficient matrix. Although, in this case, a completely different set of brain imaging features was discovered: features associated with the hippocampus. Here we see the remarkable effect of the G1-norm regularization combined with the trace norm. Hippocampus atrophy has been shown to be highly predictive of AD.

Fig. 2.

Visualization of the voxel-based morphometry modality coefficients derived from at various times (BL/M6/M12/M24). The top ten AAL regions are as follows (largest to smallest): Hippocampus_L, Amygdala_L, Hippocampus_R Temporal_Inf_R Temporal_Mid_R, Temporal_Inf_L, ParaHippocampal_L, Amygdala_R, Temporal_Mid_L, ParaHippocampal_R, Angular_R, and Temporal_Pole_Sup_L.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism.

The coefficients associated with the SNP modality in are extracted from the coefficient matrix. . Similar to two previous modalities, there was little difference between the coefficient matrices at each time point. The only orange bar in Fig. 3 is the coefficient that is associated with the rs429358 SNP: the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) gene. Schuff et al. [7] and many others have discovered that the ApoE gene is related to increased rates of hippocampus atrophy. It is surprising that no other SNPs show up given that SNPs on the same gene are frequently associated with one another. One reason for this could be that the tuning coefficient on the ℓ2,1-norm is too large.

Fig. 3.

Heatmap visualization of the SNPs along the x-axis against the corresponding coefficients derived from . The single orange line on the right-hand side is the weight associated with rs429358.

4. Conclusion

Learning effective mappings between different input and output modalities is an important research task in AD research. In the proposed Joint High-Order Multi-Modal Multi-Task Feature Learning model, we use various regularizations to learn the relationships between modalities over time. Our proposed method shows superior performance compared to traditional machine learning models.

Acknowledgement.

This research was partially supported by NSF-IIS 1423591 and NSF-IIS 1652943; NSF-IIS 1302675, NSF-IIS 1344152, NSF-DBI 1356628, NSF-IIS 1619308, NSF-IIS 1633753, and NIH R01 AG049371; NIH R01 EB022574, NIH R01 LM011360, NIH R01 AG19771, NIH U19 AG024904, and NIH P30 AG10133.

Footnotes

ADNI—Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimers Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (ad-ni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: https://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

References

- 1.Alzheimer, Association, Sciencestaff, Alzorg: 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures (2017). 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Candès EJ, Recht B: Exact matrix completion via convex optimization. Found. Comput. Math 9(6), 717 (2009). 10.1007/s10208-009-9045-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galton CJ, et al. : Differing patterns of temporal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease and semantic dementia. Neurology 57(2), 216–225 (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu L, Wang H, Yao X, Risacher S, Saykin A, Shen L: Predicting progressions of cognitive outcomes via high-order multi-modal multi-task feature learning. In: IEEE ISBI 2018, pp. 545–548 (2018) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nie F, Huang H, Cai X, Ding CH: Efficient and robust feature selection via joint ℓ2,1-norms minimization. In: NIPS 2010, pp. 1813–1821 (2010) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Risacher SL, et al. : Longitudinal MRI atrophy biomarkers: relationship to conversion in the ADNI cohort. Neurobiol. Aging 31(8), 1401–1418 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuff N, et al. : MRI of hippocampal volume loss in early Alzheimers disease in relation to ApoE genotype and biomarkers. Brain 132(4), 1067–1077 (2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen L: Whole genome association study of brain-wide imaging phenotypes for identifying quantitative trait loci in MCI and AD: a study of the ADNI cohort. NeuroImage 53(3), 1051–1063 (2010). imaging Genetics [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, et al. : Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. NeuroImage 15(1), 273–289 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, Nie F, Huang H, Ding C: Heterogeneous visual features fusion via sparse multimodal machine. In: IEEE CVPR 2013, pp. 3097–3102 (2013) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Nie F, Huang H: Multi-view clustering and feature learning via structured sparsity. In: International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2013), pp. 352–360 (2013) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H: Identifying quantitative trait loci via group-sparse multitask regression and feature selection: an imaging genetics study of the ADNI cohort. Bioinformatics 28(2), 229–237 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, et al. : Identifying AD-sensitive and cognition-relevant imaging biomarkers via joint classification and regression In: Fichtinger G, Martel A, Peters T (eds.) MICCAI 2011. LNCS, vol. 6893, pp. 115–123. Springer, Heidelberg: (2011). 10.1007/978-3-642-23626-615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, et al. : Identifying disease sensitive and quantitative trait-relevant biomarkers from multidimensional heterogeneous imaging genetics data via sparse multimodal multitask learning. Bioinformatics 28(12), i127–i136 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, et al. : From phenotype to genotype: an association study of longitudinal phenotypic markers to alzheimer’s disease relevant SNPs. Bioinformatics 28(18), i619–i625 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, et al. : High-order multi-task feature learning to identify longitudinal phenotypic markers for alzheimer’s disease progression prediction. In: NIPS 2012, pp. 1277–1285 (2012) [Google Scholar]