Abstract

The Tribbles family of pseudokinases recruits substrates to the ubiquitin ligase COP1 to facilitate ubiquitylation. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) family transcription factors are crucial Tribbles substrates in adipocyte and myeloid cell development. We found that the TRIB1 pseudokinase was able to recruit various C/EBP family members and that the binding of C/EBPβ was attenuated by phosphorylation. To explain the mechanism of C/EBP recruitment, we solved the crystal structure of TRIB1 in complex with C/EBPα, which revealed that TRIB1 underwent a substantial conformational change relative to its substrate-free structure and bound C/EBPα in a pseudosubstrate-like manner. Crystallographic analysis and molecular dynamics and subsequent biochemical assays showed that C/EBP binding triggered allosteric changes that link substrate recruitment to COP1 binding. These findings offer a view of pseudokinase regulation with striking parallels to bona fide kinase regulation—by means of the activation loop and αC helix—and raise the possibility of small molecules targeting either the activation “loop-in” or “loop-out” conformations of Tribbles pseudokinases.

INTRODUCTION

Protein kinases are a pervasive class of signaling protein that transduce all manner of biological signals. Kinase catalytic activity is controlled by a range of mechanisms, which converge on alignment of the catalytic and regulatory spines (1). Among the ~500 protein human protein kinase domains, around 10% are regarded as pseudokinases because they lack key catalytic features. Sequence variations that can turn a kinase into a pseudokinase include mutation of catalytic resides, substitutions that block adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) binding, or disruption of regulatory spine residues (2). Like their catalytically active counterparts, pseudokinases play roles in many signaling pathways but do so without phosphorylating substrates. These functions can be broadly categorized as allosteric regulation of active kinases, acting either as scaffolds for protein-protein interactions or as signaling switches (2, 3).

The Tribbles family of proteins occupies a dedicated branch of the kinome composed of four members—TRIB1, TRIB2, TRIB3, and the more distantly related STK40 (also known as SgK495) (4). The family derives its name from the Drosophila tribbles protein (5,6) and shares a common domain architecture: They have a variable N-terminal extension, a pseudokinase domain, and a C-terminal extension that binds to the ubiquitin E3 ligase COP1 (Fig. 1A). The pseudokinase and COP1-binding motif are key for the function of Tribbles proteins—by binding to substrates through their pseudokinase domain and to COP1 through their C terminus, they act as substrate adaptors to facilitate ubiquitylation by COP1.

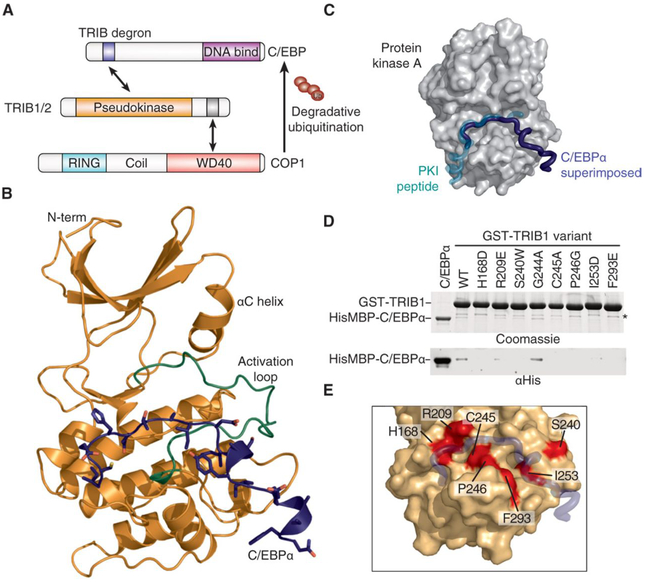

Fig. 1. The TRIB1-C/EBPα degron complex.

(A) Schematic illustrating degradation of C/EBPα by TRIB1-COP1. (B) Crystal structure of the TRIB1-C/EBPα degron complex, with TRIB1 shown predominantly in orange with a green activation loop and C/EBPα in blue. (C) Comparison of the C/EBPα binding mode (blue) with that of the prototypic substrate-like PKI (turquoise) in complex with PKA [gray surface; Protein Data Bank (PDB) 1ATP]. To generate the overlay, the TRIB1-C/EBPα complex structure was superimposed on the basis of the pseudokinase and kinase domains of TRIB1 and PKA, respectively. (D) Glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown of His6MBP-C/EBPα(53–75) by wild-type (WT) GST-TRIB1(84–372) and indicated mutants, separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and visualized by Coomassie blue staining (top) or anti-His6 immunoblotting (bottom). A nonspecific band that copurifies with GST-TRIB1 is indicated with an asterisk. (E) Structural representation of mutants that disrupt C/EBPα binding. TRIB1 is shown as an orange surface and C/EBPα in blue, with TRIB1 mutants that disrupt binding shown in red.

Human Tribbles proteins are implicated in wide-ranging signaling processes. TRIB3 is known to affect metabolism by binding and inhibiting the metabolic regulatory protein kinase AKT and by recruiting acetyl–coenzyme A carboxylase for degradation (7, 8). In contrast to inducing degradation, TRIB3 can stabilize the oncogenic PML-RARα fusion protein, preventing its sumoylation and ubiquitylation (9). In addition, TRIB1 to TRIB3 have all been reported to both promote and suppress mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling (10–13).

Perhaps the most well-established role of Tribbles proteins is regulating CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) family transcription factors (14–17). The C/EBP family is composed of six members in humans (α, β, γ, δ, ε, and ζ). Further diversity arises because most family members can be translated as splicing isoforms, and family members can form either homodimers or heterodimers (18). C/EBP transcription factors recognize a characteristic CCAAT DNA sequence to regulate proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism, particularly of hepatocytes, adipocytes, and hematopoietic cells (15,18–20). Among the Tribbles, TRIB3 appears to not influence C/EBPs, whereas TRIB1, TRIB2, and STK40 are all capable of triggering degradation of selected C/EBPs by recruiting them to COP1 for ubiquitination (14, 21). Through their ability to control C/EBP and myeloid development, overexpression of Trib1 and Trib2 in mice can cause development of acute myeloid leukemia with high penetrance (14, 22), and TRIB1 deficiency results in a loss of tissue- resident M2-like macrophages (15). Genome-wide association studies have also linked TRIB1 to circulating liver enzymes and plasma lipids (23, 24), which has subsequently been linked to posttranslational control of C/EBP-regulated transcription (25).

Crystal structures of the TRIB1 pseudokinase domain have revealed a deprecated N-terminal lobe and ATP-binding site, which is consistent with the inability of TRIB1 to bind ATP (17). Notably, the C-terminal COP1-binding motif of TRIB1 can bind to the pseudokinase domain in an autoinhibitory manner (17), which is mutually exclusive with the motif binding to the COP1 WD40 domain (26). Here, we used a combination of crystallography, molecular dynamics (MD), and biochemistry to investigate the mechanism that allows the release of TRIB1 autoinhibition. Solving the structure of TRIB1 bound to its prototypical substrate, C/EBPα, revealed that TRIB1 undergoes a marked conformational change upon substrate binding. Such conformational changes have important implications for assembly of an active complex with COP1 and potentially for susceptibility of Tribbles pseudokinases to small-molecule inhibitors.

RESULTS

Structure of the TRIB1-C/EBPα complex

To understand the basis for recruitment of C/EBP family transcription factors, we sought to solve the structure of the TRIB-C/EBPα complex. Crystals of the complex were successfully grown by fusing the TRIB1 recognition degron (the sequence mediating protein interactions that regulate degradation) of C/EBPα to the C terminus of TRIB1 (fig. S1). The structure was solved to a resolution of 2.8 Å (Table 1). There are two complexes in the asymmetric unit, which have the C/EBPα peptide defined for residues 55 to 74 and 57 to 67, respectively (the former complex is displayed in subsequent figures; both complexes and electron density maps are included in fig. S2). The activation loop of TRIB1 in both complexes was fully resolved (Fig. 1B), revealing that it adopts a position markedly different than the conformation seen in substrate-free TRIB1 (17). The activation loop folds toward the αC helix and generates a binding site for the C/EBPα degron. This binding mode is effectively pseudosubstrate-like, as demonstrated by comparison with that of the prototypical substrate-like protein kinase inhibitor (PKI) peptide in complex with protein kinase A (PKA) (Fig. 1C). All of the C/EBPα degron residues previously shown to be required for binding make direct contact with TRIB1 (17). Namely, Ile55, Glu59, Ser61, Ile62, and Ile64 are part of an extended peptide that spans TRIB1 and leads to a helical turn containing Tyr67 and Ile68, which lie in a cleft alongside the αG helix of TRIB1.

Table 1. Summary of crystallographic data and refinement.

Rmerge = Σhkl Σi ∣Ii – <I> ∣/–Σhkl ΣIi, where Ii is the intensity of the ith observation, <I> is the mean intensity of the reflection, and the summations extend over all unique reflections (hkl) and all equivalents (i), respectively. Rpim is a measure of the quality of the data after averaging the multiple measurements and Rpim = Σhkl [n/(n – 1)]1/2 Σi ∣Ii(hkl) – <I(hkl)>∣/Σhkl Σi Ii(hkl), where n is the multiplicity (other variables as defined for Rmerge).

| TRIB1-C/EBPα | |

|---|---|

| Beamline | AS-MX2 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9537 |

| Resolution (outer shell) (Å) | 48.7–2.8 (2.95–2.8) |

| Space group | P6122 |

| Unit cell parameters | a = 98.8 Å |

| b = 98.8 Å | |

| c = 332.7 Å | |

| α = 90° | |

| β = 90 ° | |

| γ = 120° | |

| Rmerge (outer shell) | 0.077 (1.992) |

| Rpim (outer shell) | 0.035 (0.879) |

| Mean I/σI (outer shell) | 19.8 (1.5) |

| Completeness (outer shell) | 99.8 (99.1) |

| Multiplicity (outer shell) | 10.4 (10.7) |

| Total no. of reflections | 258,141 (37,340) |

| No. of unique reflections | 24,777 (3,491) |

| Mean (I) half-set correlation CC(1/2) (outer shell) | 1.000 (0.609) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 82.1 |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Rcryst | 0.220 |

| Rfree | 0.276 |

| Average B factor overall (Å2) | 113 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics (%) | |

| Favored regions | 93.1% |

| Allowed regions | 6.5% |

| Outliers | 0.4% |

| PDB entry | 6dc0 |

To experimentally validate the TRIB1 residues involved in the interface, we generated a panel of mutants in a GST-TRIB1 fusion protein and tested their ability to bind His6MBP-C/EBPα (Fig. 1, D and E). Mutants were designed to include residues that directly contact C/EBPα or to test differences between binding capabilities of TRIB1 and TRIB3 (described further in the next paragraph). In pulldown analysis, critical residues spanned the C/EBPα binding site—either directly contacting C/EBPα (His168, Arg209, and Phe293) or partaking in both substrate binding and stabilization of the activation loop in a competent conformation (Cys245, Pro246, and Ile253). The six TRIB1 mutants with impeded C/EBPα binding were identical in TRIB2 consistent with the ability of TRIB1 and TRIB2 to bind C/EBPα with similar affinities (fig. S3) and subsequently induce its degradation in cells and drive development of acute myeloid leukemia in mice (14).

When considering why TRIB1, TRIB2, and STK40, but not TRIB3, have been reported to degrade C/EBP proteins (14, 21), the TRIB1-C/EBPα structure provides some insight. In brief, many residues that bind the C/EBP degron are conserved in TRIB3, but there are subtle differences across the degron binding site (fig. S4A). None of these differences obviously precludes binding, but the cumulative effect may decrease binding affinity to subfunctional levels. Although we have not exhaustively substituted residues between TRIB1 and TRIB3, an R209E TRIB1 mutant had decreased binding to C/EBPα (Fig. 1D)—the equivalent of Arg209 is a cysteine residue in TRIB3. Another possibility is an indirect effect through conformational dynamics of the activation loop. For instance, the residue equivalent to Ser240 in TRIB1 and TRIB2 is a tryptophan in human TRIB3 and conserved as a tryptophan in TRIB3 from humans to mice. The S240W mutant of TRIB1 has decreased C/EBPα binding (Fig. 1D), although Ser240 does not directly contact the substrate (Fig. 1E). TRIB1 G224A, which substitutes a TRIB3 residue directly contacting the substrate, had no apparent effect on binding (Fig. 1D and fig. S4A). One possible explanation is that a tryptophan in this position could stabilize the inactive state by binding the hydrophobic pocket occupied by either the N-terminal Ile55 of the C/EBPα degron in substrate-bound TRIB1 or Leu239 in substrate-free TRIB1 (fig. S4B). However, further studies specific to TRIB3 are required to test such a hypothesis.

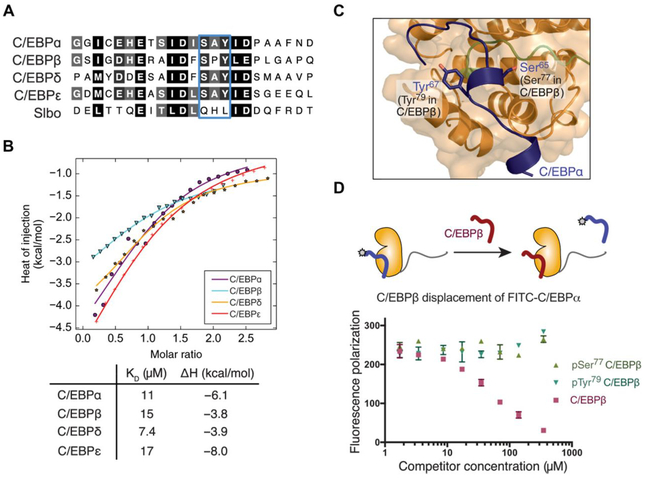

TRIB1 and C/EBP family members

Among their broad functions, C/EBP transcription factors coordinately regulate myeloid cell and adipocyte differentiation, with different family members predominating at specific phases of differentiation. However, there is some sequence variation in the Tribbles recognition degron of different C/EBP transcription factors (Fig. 2A)—C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and C/EBPε each contain a sequence similar to the C/EBPα degron. Although we are unable to rule out more cryptic degrons in C/EBPγ and C/EBPζ, their large truncations and divergent domain structures meant that we were unable to identify any contiguous degron-like sequences. We first sought to test whether C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and C/EBPε could also be bound by TRIB1 and subsequently whether sequence variations might alter the efficacy of TRIB1 binding. Using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), we observed that TRIB1 bound to C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and C/EBPε peptides fused to maltose-binding protein (MBP) with dissociation constants ranging from 7.4 to 17 μM (Fig. 2B). Such affinities suggest that C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and C/EBPε all contain functional TRIB1 degrons that bind TRIB1 with similar affinity.

Fig. 2. TRIB1 binds various C/EBPs and can be antagonized by phosphorylation.

(A) Alignment of the TRIB degron from various human C/EBP proteins, and the Drosophila C/EBP ortholog, Slbo. (B) ITC of indicated MBP-fused C/EBP degrons injected into TRIB1(84–372). Data points represent mean of duplicate titrations, following buffer titration subtraction. (C) Detailed view showing the integral role of Ser65 and Tyr67 in C/EBPα degron binding. Phosphorylation has been reported on the equivalent residues in C/EBPβ (Ser77 and Tyr69). (D) Fluorescence polarization displacement assay of FITC-C/EBPα degron from TRIB1 by unmodified, Ser77-phosphorylated, or Tyr79-phosphorylated C/EBPβ peptide. Data are means ± SEM of three independent replicates from one purified TRIB1 stock.

To investigate which residues within the C/EBP degron contribute most strongly to TRIB1 binding, we performed a 1-μs MD simulation based on the TRIB1-C/EBPα structure. Plotting the root mean square fluctuation of C/EBPα peptide reiterated that the stretch from Glu59 to Ala72 represented the most stable portion of the peptide and included the main binding determinants (fig. S5). This finding is consistent with several lines of evidence: Previous binding studies of mutant C/EBPα peptides revealed a concentration of important binding residues in this region (17); the second complex within the asymmetric unit of the crystal structure was well defined only for residues 57 to 67; and this segment contains the highest level of sequence identity between C/EBP family members.

Effect of C/EBPβ phosphorylation on TRIB1 binding

The observation that TRIB1 can bind various C/EBP family members with similar efficacy is interesting in light of previous observation that TRIB1 can affect C/EBPα, but not C/EBPβ, in certain cases (15) and other scenarios where C/EBPα and C/EBPβ are regulated equally by TRIB1 (27). These observations beg the question of whether further mechanisms control C/EBP degradation depending on cell type or developmental stage. To explore additional layers of regulation, we analyzed data from phosphosite.org and observed that C/EBPβ is phosphorylated at Ser77 and Tyr7 within its Tribbles degron. Tyr79 phosphorylation of C/EBPβ occurs via c-Abl and Arg nonreceptor tyrosine kinases, resulting in stabilization of C/EBPβ (28), while Ser77 is phosphorylated in a Ras-dependent manner (29). In the TRIB1-C/EBPα structure, the equivalent serine and tyrosine residues of C/EBPα were directly involved with binding TRIB1 (Fig. 2C). To test the effect of C/EBPβ degron phosphorylation, we developed a competition assay based on fluorescence polarization (Fig. 2D). In this assay, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled C/EBPα peptide was competitively displaced by an unmodified C/EBPβ degron peptide. In contrast, Ser77-phosphorylated or Tyr79-phosphorylated C/EBPβ degron peptide showed no ability to displace FITC-C/EBPα, even up to concentrations of 350 μM. Loss of TRIB1 binding after Tyr79 phosphorylation suggests a direct mechanism to explain posttranslational stabilization of C/EBPβ by c-Abl (28) based on protection from degradation by TRIB1-COP1. Similarly, phosphorylation of Tyr79 by proline-directed Ser/Thr kinases such as CDK2 or MAPKs could represent a further mechanism by which C/EBP protein abundance can be protected from degradation by COP1-Tribbles complexes under specific circumstances (29).

Conformational changes induced by substrate binding

Previous structures of TRIB1 have shown that the pseudokinase domain contains an unusual αC helix that forms a binding site for the C-terminal COP1-binding motif (17). TRIB1 and TRIB2 also contain a unique Ser-Leu-Glu (SLE) sequence at the N terminus of the activation loop—as opposed to Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG) that is seen in most active kinases—which can block the putative ATP-binding pocket. The structure of substrate-bound TRIB1 here revealed distinct conformational changes upon substrate binding (Fig. 3). Analysis of these conformational changes delineated a clear allosteric mechanism to link substrate binding on one side of TRIB1 to release of the COP1-binding motif from its binding site on the αC helix—in effect release of TRIB1 autoinhibition (Fig. 3 and movie S1).

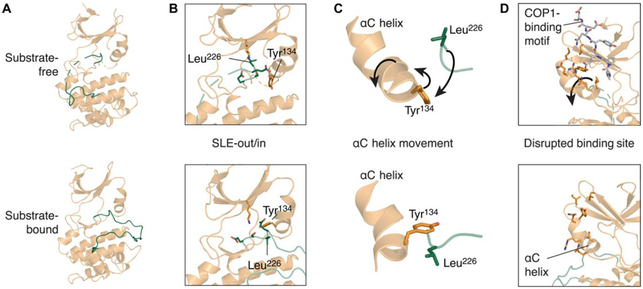

Fig. 3. TRIB1 conformational changes upon substrate binding.

(A to D) Comparison of structures of substrate-free (top; PDB ID 5CEM) and C/EBPα-bound TRIB1 (bottom; this work). (A) Overview from the substrate-binding side of the molecule. (B) SLE motif and surrounding residues within the active site from the same orientation as (A). (C) Simplified view showing the relative organization of the αC helix, Tyr134, and Leu226 from the opposite orientation to (A) and (B). (D) Position of the αC helix and residues that contact the C-terminal tail of TRIB1 in substrate-free TRIB1; orientation as described in (C). Movement of selected features upon C/EBPα binding are indicated with arrows (top), and residues are selectively depicted as sticks for clarity.

Upon binding to C/EBPα substrate, the activation loop became fully ordered, folding between the N- and C-terminal lobes to form the substrate-binding site (Fig. 3A and Fig. 1). With this, rearrangement was a conformational change in the SLE sequence at the N terminus of the activation loop (Fig. 3B). Leu226 moved toward the αC helix, packing into a location homologous to the DFG phenylalanine of conventional kinases when they adopt their “DFG-in” conformation (1). In TRIB1, rearrangement of Leu226 was facilitated by movement of Tyr134 within the αC helix, which subsequently packed atop Leu226 to complete the regulatory spine (Fig. 3C). In this manner, the substrate-bound conformation of the TRIB1 pseudokinase can be thought to adopt an “SLE-in” conformation that is comparable to the DFG-in conformation of conventional kinases.

The existence of states that resemble inactive (SLE-out) and active (SLE-in) protein kinase structures not only is intriguing but also has striking consequences for the function of TRIB1. For the coordinated rearrangement of Tyr134 and Leu226 upon substrate binding to occur, the αC helix of TRIB1 must rotate away from the active site of the kinase. For instance, the α carbon positions of Tyr134, Ile135, and Gln136 moved by 3.2, 4.8, and 4.4 Å, respectively, relative to their positions in the substrate-free structure. Further movement was propagated through the N-terminal portion of the αC helix, and more subtle rearrangements occurred within the β4 and β5 of the N-terminal lobe. Together, these changes disrupted the docking site for the C-terminal tail of TRIB1 (Fig. 3D), making it incompatible with sequestration of the C-terminal COP1-binding site and TRIB1 autoinhibition.

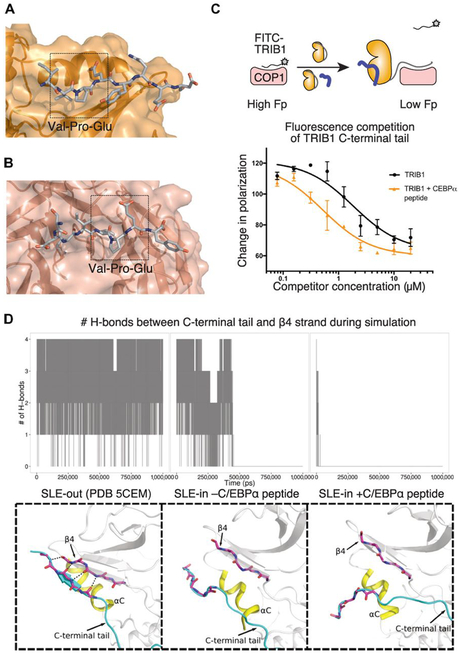

Allosteric regulation of TRIB1 autoinhibition by substrate binding

The C-terminal COP1-binding motif of TRIB1 binds to its own pseudokinase domain and the E3 ubiquitin ligase in a mutually exclusive manner (Fig. 4, A and B) (26), which necessitates the allosteric changes outlined in the previous section. To test the functional effects of the allosteric changes, we adopted an assay previously used to test COP1 binding by TRIB1 and STK40 (26, 30). Namely, TRIB1-COP1 association was inferred by displacement of a FITC-labeled TRIB1 C-terminal peptide from the WD40 domain of COP1, which was monitored by fluorescence polarization. Consistent with Uljon et al. (26) and the autoinhibited crystal structure, we observed that the C-terminal COP1-binding motif was less effective at binding COP1 when it is attached to the pseudokinase [TRIB1(84–372)] than it is as an isolated peptide (residues 349 to 367; fig. S6). Strikingly, inclusion of the C/EBPα degron peptide with TRIB1(84–372) allowed TRIB1 to more effectively displace the FITC-labeled peptide (Fig. 4C). The displacement curve for TRIB1 with C/EBPα was shifted to about 10-fold lower TRIB1 concentrations relative to TRIB1 in the absence of substrate, supporting a model where substrate binding releases autoinhibition and frees the tail to bind COP1.

Fig. 4. Allosteric release of the COP1-binding motif by substrate binding.

(A and B) Structure of the C-terminal COP1-binding motif bound to (A) the pseudokinase domain of TRIB1 (from PDB ID 5CEM) or (B) the WD40 domain of COP1 (from PDB ID 5IGO). (C) Fluorescence polarization (Fp) displacement assay of FITC-TRIB1(349–367) from the WD40 domain of COP1 by either TRIB1(84–372) alone at varying concentrations (above arrow in the diagram; black in the graph) or TRIB1 (84–372) in the presence of 10 μM C/EBPα degron peptide (below arrow in the diagram; yellow in the graph). Data are means ± SEM of three technical replicates using two independently prepared stocks of COP1. (D) Summary of MD simulations of SLE-out TRIB1 or SLE-in TRIB1 with and without substrate. The number of hydrogen bonds between the C-terminal tail and β4 strand is plotted over the time course of the simulation above, and an indicative state during the latter part of the simulation is shown below. Animated trajectories are shown in movie S2.

To further investigate the structural basis of TRIB1 allostery, we performed MD simulations comparing the dynamics of TRIB1 in its autoinhibited form, in its active conformation but without substrate, and in its active conformation in the presence of substrate. These analyses could be used to (i) visualize the effect of substrate binding on stability of the C-terminal tail of TRIB1 and (ii) infer key residues involved in the allosteric regulation of TRIB1.

First, to understand the propensity of the TRIB1 C-terminal tail to occupy its autoinhibited conformation, we analyzed the stability of the tail over the parallel simulations (movie S2). In the structure of autoinhibited TRIB1 (PDB ID 5CEM), the tail stably occupied its binding cleft atop the αC helix, maintaining multiple hydrogen bonds with the β4 strand. In contrast, initiating a simulation of TRIB1 (SLE-in) bound to C/EBPα with the C-terminal tail in an equivalent position alongside the β4 strand showed the tail rapidly dissociating from its binding site. Beginning a simulation with TRIB1 in its active (SLE-in) conformation, but without substrate present, resulted in the tail binding for an intermediate length of time but eventually dissociating. To quantify these observations, we plotted the number of hydrogen bonds between the TRIB1 C-terminal tail and the β4 strand over the course of the three simulations (Fig. 4D). This analysis highlights that the C-terminal tail is less effectively sequestered when TRIB1 occupies an active state and becomes fully destabilized when substrate binding completes the active complex.

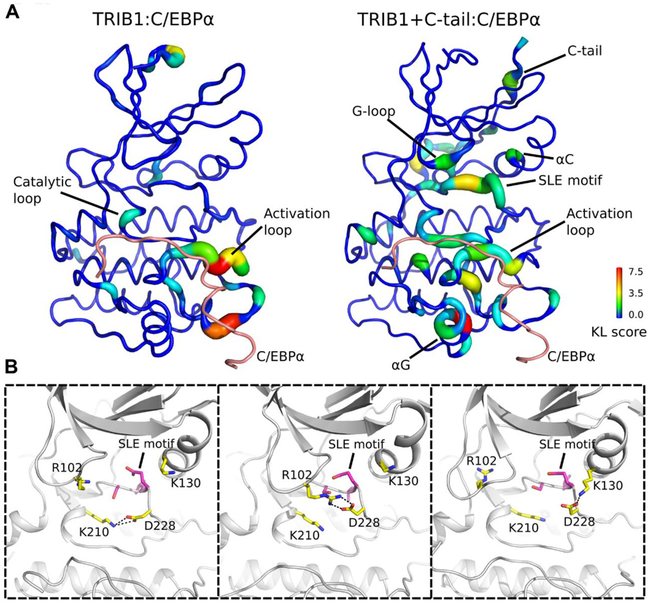

Second, to understand the key residues inherent to the allosteric mechanism, we compared the difference in torsion angle dynamics of each residue in TRIB1 using a Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence-based statistics (see Materials and Methods; Fig. 5). Quantification of KL divergence of TRIB1 without the C-terminal tail (Fig. 5A) indicated that structural regions (such as the catalytic loop and activation loop) in direct contact with C/EBPα show significant difference between substrate-bound and substrate-unbound simulations. Notably, the KL divergence profile of TRIB1 with the C-terminal tail revealed differences in torsion angle dynamics of residues not only in the substrate-binding site but also in distal regions of the pseudokinase domain, including the C-terminal tail, SLE motif, G-loop, and αC helix (Fig. 5A). In the presence of substrate, the SLE+1 aspartate (Asp228) displayed conformational flexibility in that it could make charge interactions with Lys220 from the catalytic loop, Arg102 from the glycine-rich loop, and Lys130 from the αC helix during the simulation (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the SLE motif seems to be the global hub in propagating the allosteric signals of C/EBPα substrate binding. Notably, Tyr134 in the αC helix was both intimately involved with conformational changes between the SLE-in and SLE-out states of TRIB1 (Fig. 3), and divergent in TRIB2, where it is a cysteine residue. We saw that stability of a TRIB1 Y134C mutant protein was markedly reduced to near that of TRIB2 (fig. S7). This suggests a key role for the Tyr134 position in conformational stability, which may differ between paralogs. Nonetheless, these data reinforce the key functional role of sequence features that are unique to Tribbles proteins, contributing to a mode of regulation reminiscent of active kinases.

Fig. 5. Comparative analysis of MD simulations of TRIB1 pseudokinase domain with and without C/EBPα peptide.

(A) The KL divergence of the torsion angle of each residue is shown. Motifs and residues that display differential distribution between the C/EBPα-unbound simulation and C/EBPα-bound simulation are labeled. Left: KL divergence of TRIB1 simulations without the C-terminal tail. Right: KL divergence of TRIB1 simulations with the C-terminal tail. (B) Representative snapshots from TRIB1+C-tail:C/EBPα simulation. SLE+1 aspartate (Asp228) mediates charge interaction with Lys210 from catalytic loop, Arg102 from glycine-rich loop, and Lys130 from αC helix.

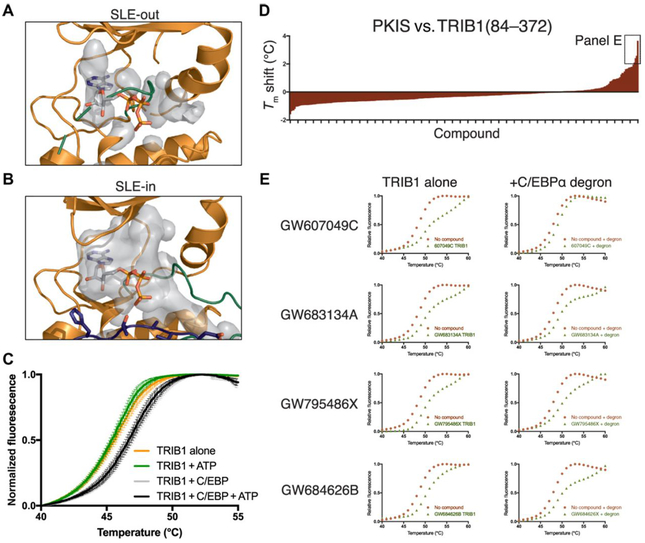

Potential for nucleotide or small-molecule binding by TRIB1

A clear consequence of conformational changes induced by C/EBPα binding is the opening of the TRIB1 active site, which, in the SLE-out state, was blocked by the activation loop (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the SLE-in state induced a large, open binding pocket (Fig. 6B). Such an open state would be consistent with reports that the closely related pseudokinase TRIB2 can bind to ATP and to small-molecule ligands (31, 32). We initially tested the effect of C/EBPα degron on the melting temperature of TRIB1(84–372) in a differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) assay (33). The addition of C/EBPα degron peptide stabilized TRIB1 (Fig. 6C, comparing orange to gray). However, further addition of 200 μM ATP did not shift the melting temperature of either TRIB1 alone (Fig. 6C, green) or the TRIB1-C/EBPα mixture (Fig. 6C, black) relative to their nucleotide-free equivalents. We also saw no change in TRIB1 stability in the presence or absence of adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) or magnesium, when C/EBPα peptide was present (fig. S8A), consistent with previous experimental studies of substrate-free TRIB1 (17). Thus, it appears that movement of the SLE motif to its SLE-in conformation is insufficient to confer the ability to bind nucleotides.

Fig. 6. TRIB1 can potentially bind small-molecule ligands but not ATP.

(A and B) Representation of the available binding cavity of TRIB1 (gray) in (A) the SLE-out conformation from PDB ID 5CEM and (B) the SLE-in conformation when bound to C/EBPα. (C) DSF melting analysis of TRIB1 or TRIB1 + C/EBPα degron peptide in the presence or absence of ATP. Points are the mean of independent triplicates from one purified TRIB1 stock, with error bars representing SEM. (D) Summary of DSF analyses of TRIB1(84–372) against the Published Kinase Inhibitor Set (PKIS) library. Tm is expressed as the difference between each compound and the mean of three dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)–only controls. The four compounds shown in more detail in (E) are indicated. (E) Individual DSF melting curves of four selected compounds (left), with additional titrations for each that include C/EBPα degron peptide (right).

Although TRIB1 does not appear capable of binding ATP in either conformation, there is no obvious steric hindrance of the rear (adenine binding) portion of the TRIB1 ATP-binding site, particularly in the SLE-in state. This is relevant because ATP-competitive inhibitors often occupy the adenine-binding portion of a kinase active site, rather than the phosphate-stabilizing regions that are defunct in TRIB1. To explore this possibility, we used DSF to screen TRIB1 against the publicly available PKI screen (34). We found several compounds that induced thermal stabilization of TRIB1 by greater than 2°C (Fig. 6D, fig. S8B, and table S1). The four hits were originally designed as inhibitors of either angiopoietin and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (TIE2 and VEGFR2) or epidermal growth factor receptor family members (EGFR and ErbB2, also known as HER2) and were built upon either the benzimidazolyl diaryl urea, furopyrimidine (both TIE2/VEGFR2-targeting), or anilino thienopyrimidine (EGFR/ErbB2-targeting) scaffold (35–37). Moreover, three of the four also induced similar stabilization of TRIB1 in the presence of C/EBPα degron peptide, whereas GW607049C induced a different melting profile in the presence and absence of degron (Fig. 6E, fig. S8B, and table S1), which could indicate binding to different conformations of TRIB1. Although further characterization is definitely required, these results offer the first suggestion that inhibitors could be developed to target TRIB1. On the basis of structural and mechanistic studies presented here, development of specific ligands that bind the SLE-out or SLE-in conformations of TRIB1 could have exciting potential to either block substrate binding or release autoinhibition of TRIB1 to promote recruitment of the COP1 ubiquitin ligase.

DISCUSSION

Tribbles pseudokinases function in concert with the COP1 ubiquitin ligase to degrade critical regulators of metabolism and transcription (4). Here, we showed that TRIB1 recognizes conserved degrons in C/EBP family members with similar efficacy and that binding of C/EBPβ was antagonized by C/EBPβ phosphorylation. We also reported the structure of TRIB1 in complex with the degron from its canonical substrate, C/EBPα. The mechanism of C/EBPα binding by TRIB1—a pseudosubstrate-like binding mode—couples substrate binding on one face of TRIB1 to release the C-terminal tail on the opposing face of the molecule. Such a mechanism not only seems likely to have important consequences for protecting TRIB1 from unproductive degradation by COP1 but also offers exciting potential when considering ligands designed to bind the TRIB1 active site.

Pseudokinases are not constrained by the need to perform catalysis and hence have evolved as diverse mediators of signal transduction via three major mechanisms: allosterically activating other enzymes, acting as signaling switches, or scaffolding protein-protein complexes (2, 3). There are few examples of pseudokinase structures captured in both inhibited and “active” states, but the mechanism described here for TRIB1 bears remarkable resemblance to regulation of conventional kinases. However, it is facilitated by unique structural features of TRIB1. For instance, the αC helix is commonly mobile in conventional kinases (1). In TRIB1, the C-terminal portion of the αC helix appears somewhat distorted—potentially by the presence of Pro133—relative to conventional kinases and undergoes a subtle unwinding between the substrate-free and substrate-bound structures (Fig. 3D). Moreover, in addition to having an SLE motif rather than a DFG motif, TRIB1 to TRIB3 all have a glutamate preceding the SLE, which is unique, stabilizes the autoinhibited state of TRIB1, and exhibits increased KL divergence in MD simulations of substrate-free and substrate-bound TRIB1-C/EBPα (Fig. 5). Overall, the mechanism described in this work offers an intriguing example of sequence features that are divergent between pseudokinases and kinases maintaining orthologous function as an allosteric switch. In conventional kinases, binding of regulators to the αC helix can stabilize the regulatory spine and promote the active conformation and substrate binding (1). In the case of TRIB1, it appears that the αC helix and substrate binding remain intimately linked—with substrate binding on one side of the molecule being coupled to interactions between the C-terminal tail and the αC helix. Whether similar mechanisms control protein-protein interactions in other pseudokinases, or active kinases, is an interesting proposition.

Foulkes et al. (32), published alongside this report, showed that TRIB2 also binds its own C-terminal tail and thus potentially also adopts an autoinhibited conformation that facilitates allosteric regulation. Although no structures are available for TRIB2 or TRIB3, the structure of the STK40 pseudokinase domain was recently reported (30). However, STK40 is the most divergent Tribbles family member and does not share the SLE-type motif or preceding glutamate residue. In this sense, it appears unlikely to share the same allosteric switch mechanism as TRIB1 and may be constitutively active with regard to substrate binding. The impact of such for STK40 stability and biological functions independent of canonical Tribbles family members will be an area of some interest.

C/EBP transcription factors play pleiotropic roles in development of adipocytes and myeloid cells. The importance of C/EBPs in myeloid development is illustrated by mutations in C/EBPα that occur in ~10% of acute myeloid leukemia patients (38) and the critical transcriptional role of C/EBPβ in multiple myeloma (39). Many of the biologically characterized roles of TRIB1 and TRIB2—for instance, regulation of lipid metabolism or macrophage development—can be traced to their ability to control the abundance of C/EBPα in particular. The identification of the Tribbles degron present in the p42, but not the dominant-negative p30 isoform of C/EBPα, suggested one mechanism by which Tribbles may selectively control a single transcription factor (17). Our findings reported here now show that the Tribbles degron is conserved in four of six C/EBP family members, of which all but C/EBPδ are similar to C/EBPα in that they also have short isoforms that lack a Tribbles degron. Because leucine zipper transcription factors can form either homodimers or heterodimers, which may contain no, one, or two Tribbles degrons, there appears to be ample opportunity for gradation of C/EBP ubiquitylation by COP1-TRIB1/2, where complexes containing two degrons are preferentially degraded by Tribbles, over complexes that might be recruited less avidly. In addition, because our C/EBP binding studies were performed with a recombinant degron sequence, we cannot rule out that additional sequences or posttranslational modifications may modify binding affinity and degradation in the context of full-length C/EBP proteins.

Our binding studies show the potential for C/EBPβ to be protected from TRIB1 binding by phosphorylation (Fig. 2D). Such protection may have clinical relevance when considering tumors with constitutively activated kinases upstream of C/EBPβ. Namely, given the role of EBPβ in Ras-induced transformation and myeloid cancers, it is tempting to speculate that pharmacologically preventing EBPβ phosphorylation could make it susceptible to Tribbles-mediated degradation and offer benefit in specific cancers (28, 29,40). Phosphorylation of EBPβ further adds to the complexity of COP1-based ubiquitination and phosphorylation, given modulation of ETS family transcription factor degradation by Src family kinases (41, 42), and to the fundamental role of degrons within key substrates in cancer development (43).

Although the capability of TRIB2 to bind ATP appears not to be realized in either the SLE-in form or the SLE-out form of TRIB1 (Fig. 6) (31), this work opens the intriguing possibility that small- molecule inhibitors targeted toward the active site of Tribbles could be used to block function. An exciting coincident report by Foulkes et al. suggests that small-molecule inhibitors that covalently target a cysteine-rich segment in the αC helix of TRIB2 can induce its degradation (32). The fact that these inhibitors were also originally designed against EGFR offers some overlap with the binding profile shown here for TRIB1. The chances of such overlap were likely increased by our having screened an identical library, which is enriched in EGFR-targeted ligands, to that screened by Foulkes et al. A more extensive search of chemical space is warranted to find more potent binders of TRIB1. The mechanism revealed in this work offers an exciting incentive for finding Tribbles-targeting small molecules—despite having poor ATP-binding propensity, the active-site pocket is intimately linked to regulation of TRIB1, and binding of inhibitors around the SLE sequence and αC helix may have drastic implications for the fate of TRIB1 or TRIB2. When further high-affinity binders can be identified, it will be especially important to understand possible stabilization or destabilization of SLE-in or SLE-out conformation, which could subsequently affect protein lifetime and function in cells. Such potential is well exemplified by Foulkes et al. in degradation of TRIB2 by EGFR-targeted ligands (32).

Targeting pseudokinases with small molecules is an exciting area of development. For instance, small molecules that stabilize the KSR pseudokinase antagonize RAF heterodimerization and subsequently Ras signaling (44), and molecules targeting the HER3 pseudokinase modulate its heterodimerization with kinase-active EGF family receptors and induce degradation of HER3 (45). The distinct sequence features within the active site of TRIB1 may offer several possibilities for developing specific inhibitors. It remains a tantalizing prospect that high-affinity small molecules could manipulate the allosteric mechanism described here to protect substrates, or promote Tribbles degradation, in cancers promoted by Tribbles pseudokinases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification by GST pulldown

All bacterial constructs (TRIB1 and C/EBP) were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells. COP1 was expressed in insect cells.

TRIB1(84–372), TRIB2(53–343), and TRIB1(84–343) linked by a -GSGSSGGPG-linker to C/EBPα(53–75) were cloned into modified pET-LIC vectors incorporating an N-terminal 6× His tag and a 3C protease cleavage site. C/EBPα(53–75), C/EBPβ(64–86), C/EBPδ(50–72), and C/EBPε(31–53) all fused to MBP were cloned into modified pET-LIC vectors incorporating an N-terminal 6× His tag followed by MBP and a 3C protease cleavage site.

Cell pellets were resuspended in purification buffer [50 mM tris (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 10% (w/v) sucrose] supplemented with lysozyme (0.2 mg/ml) and benzonase (80 U/ml). Cells were lysed by sonication (Sonifier, Heat Systems Ultrasonics). Protein was initially purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography (HIS-Select resin, Sigma-Aldrich). Proteins were eluted with purification buffer containing 300 mM imidazole. Protein-containing fractions were pooled and digested overnight with 3C protease and 2 mM dithiothreitol. The protein was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Increase column (GE Life Sciences) [10 mM Hepes (pH 7.6), 300 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM tris(2-(TCEP)] or anion exchange (RESOURCE Q). The core peak fractions were pooled and snap-frozen for storage at −80°C.

Mutations were generated in Trib1(84–372) in a modified pGEX-LIC vector incorporating an N-terminal GST tag using QuikChange mutagenesis. Cell pellets from expression of wild-type and mutant TRIB1 were resuspended in purification buffer and supplemented with lysozyme (0.2 mg/ml) and benzonase (80 U/ml), and cells were lysed by sonication. The soluble fraction was bound to GST Sepharose resin (Amersham Biosciences) and analyzed for purity by SDS-PAGE. GST-TRIB1 was incubated with 500 μM C/EBPα(53– 75) fused to MBP at 4°C for 20 min using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). After incubation, the resins were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and 0.02% (v/v) Tween 20. Samples were then resuspended in SDS sample buffer and visualized on 12 to 18% gradient SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie R250.

The COP1 WD40 domain (376–731) was expressed in the Trichoplusia ni (Tni) and Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cell lines using baculovirus produced in Sf9 cells. All cells were purchased from Expression Systems and cultured in ESF 921 medium at 27°C, shaken at 125 rpm. The Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system (Invitrogen) was used, as per the manufacturer’s instructions, to produce COP1 WD40 baculovirus stocks, except that FuGENE 6 (Promega) was used as the transfection reagent. Cells were plated at a density of 8.0 × 105 cells/ml and allowed to grow until logarithmic growth was achieved, as indicated by a density of 1.0 × 106 cells/ml. Subsequently, cells were inoculated with COP1 WD40 baculovirus with a multiplicity of infection of 1 and incubated at 28°C for 72 hours (Sf9) or 48 hours (Tni). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1000g for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10% (v/v) glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole supplemented with DNase I (AppliChem) and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (p8340, Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were lysed using an EmulsiFlex-C3, and the soluble fraction was purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography (HIS-Select resin, Sigma-Aldrich). COP1 WD40 protein was eluted from resin in lysis buffer including 500 mM imidazole. The protein was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Increase column (GE Life Sciences) [150 mM NaCl and 10 mM Hepes buffer (pH 7.6)].

Crystallization and structure determination

We initially attempted crystallization of both the TRIB1 pseudokinase and pseudokinase plus C-terminal tail with free C/EBPα(53–75) peptide and the C/EBPα peptide fused to other proteins. We were able to eventually crystallize TRIB1(84–343) in fusion with C/EBPα(53–75), linked by a GSGSSGGPG linker. Initial crystals were grown by vapor diffusion, mixing fusion protein (~12.2 mg/ml) with 2.8 M sodium acetate (salt) and 0.1 M bis-tris propane (pH 7). Initial hits were refined using additive screening and soaking experiments, and crystals for data collection were grown in 2.8 M sodium acetate and 0.1 M bis-tris propane (pH 7) with 5% sodium citrate mother liquor diluted to 75 and 80% and drop ratios of 2:1 and 3:1. The crystals were cryoprotected in mother liquor supplemented with 25% glycerol. In attempts to improve diffraction, the crystal that eventually yielded the best resolution included 1 mM ATP in the cryoprotectant, but there was no electron density attributable to nucleotide in the final structure. Data were collected at the MX2 beamline of the Australian Synchrotron (Table 1) and processed using XDS and AIMLESS (46, 47). The structure was solved by molecular replacement in Phaser using the pseudokinase portion of PDB ID 5CEM as a model (48). Rebuilding was performed in Coot (49), and the structure was refined against diffraction data to a final resolution of 2.8 Å using REFMAC (50).

MD simulations: Structural modelling, system preparation, and simulation

The SLE-out conformation of TRIB1 (residues 88 to 359) was modeled on the basis of the PDB structure 5CEM (17). Missing residues of the αC-β4 loop (residues 140 to 141), activation loop (residues 229 to 237), and part of the C-terminal tail (residues 343 to 356) were fixed using the automodel class in Modeller (51). The C-terminal tail (residues 341 to 364) was incorporated into the SLE-in-TRIB1:C/EPBα complex using PDB ID 5CEM as the template. The simulations were performed in the presence and absence of C/EPBα peptide.

All MD simulations were performed using GROMACS version 5.1.2 (52). Specifically, the protein was parameterized using amber99sb-ildn force field and solvated with TIP3P water model (53). The protein was centered in a dodecahedron box, with the distance between the solute and the box larger than 1 nm in all directions. Ions (Na+ and Cl−; 0.1 mM) were added to the system by randomly replacing solvent molecules to neutralize the charge of the system. Steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms were used in conjunction to minimize the potential energy of the system so that the maximum force (Fmax) is less than 100 kJ mol−1 nm−1. LINCS (linear constraint solver) algorithm was used to constraint bonded interactions. Verlet cutoff scheme is used to maintain neighbor list (54). Long-range electrostatic interactions are calculated on the basis of particle-mesh Ewald method (55). Temperature equilibration was done in canonical ensemble (NPT) for 200 ps using V-rescale thermostat (56). Isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) was then maintained through Berendsen barostat at 1.0 bar for 200 ps. The productive simulations were carried out at NPT ensemble for 1 μs. The torsion angle analysis of the trajectory was calculated using the gmx chi module of GROMACS.

KL divergence analysis

KL divergence is a statistical measure of how two probability distributions differ from each other. In this analysis, we focused on the distribution of the torsion angles (Φ, Ψ, and X) of each residue in TRIB1 during the MD simulations. We used the C/EBPα-unbound form as the reference state and C/EBPα-bound form as the target state. MutInf package was used to perform the KL calculation (57). Specifically, we split the 100 to 1000 ns of our MD data into four equal length blocks as the bootstrapping set and discretized the torsion angle (Φ, Ψ, or X) distribution of each residue with a bin width of 15°. The sum of the KL divergence of all angles of a given residue was reported as the KL score for that residue. The KL score was then mapped to the TRIB1 structure and visualized using the putty representation of PyMOL.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC experiments were performed at 30°C using a VP-ITC calorimeter (GE Healthcare). TRIB1(84–372) and MBP fusion proteins of C/EBPα(53–75), C/EBPβ(64–86), C/EBPδ(50–72), and C/EBPε(31–53) were initially purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography followed by size-exclusion chromatography using a matched buffer consisting of 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.6), 300 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM TCEP. C/EBP (200 mM) was injected into 20 mM TRIB1(84–372). Baseline corrections and integration were performed using NITPIC (58), isotherms were fit to a single site-binding model using SEDPHAT (59), and figures were generated using GUSSI (http://biophysics.swmed.edu/MBR/software.html).

Fluorescence polarization

Fluorescence polarization of synthetic TRIB1 and C/EBPα peptides bearing an N-terminal FITC fluorophore (Mimotopes) was measured as indicated in combination with purified COP1 WD40 domain (376 to 731), TRIB1 (84 to 372), TRIB2 (53 to 343), or C/EBPβ degron peptide. COP1-TRIB1 and TRIB½-C/EBPα KD (dissociation constant) determination was performed in black 384-well microplates (Greiner Bio-One) with a final reaction volume of 30 αl, whereas TRIB1-C/EBPα displacement by C/EBPβ was performed in 96-well format with a final reaction volume of 60 μl. For COP1 displacement measurements, the COP1 WD40 domain and TRIB1- FITC peptide (349 to 367) were kept at a constant concentration of 1.5 μM and 25 nM, respectively, diluted in a fluorescence polarization buffer [300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, 0.5 mM TCEP, and 0.02% (v/v) Tween 20]. The concentrations of competing ligand, either TRIB1 protein or TRIB1 peptide, were varied from 0 to 20 μM. Where necessary, the reactions were supplemented with C/EBPα peptide (53 to 75) at a concentration of 10 μM. Once all reactions were prepared, they were allowed to incubate at room temperature for 20 min and measured using the POLARStar (BMG Tech) plate reader. Following this method, the data from three independent experiments were obtained and plotted as the means ± SEM using Prism 7. For TRIB1-C/EBPα displacement by C/EBPβ, 1.5 μM TRIB1 and 25 nM C/EBPα-FITC peptides were incubated together, C/EBPβ was titrated at concentrations from 43 nM to 350 μM, and measurement was performed in an equivalent manner.

Differential scanning fluorimetry

The PKI screening library in 384-well format was received from Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC)–University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) at 10 mM stock concentration. The stock was prediluted to 2 mM before aliquoting into black 384-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) using the mosquito LCP (TTP LabTech) and screening against TRIB1 at a final compound concentration of 40 μM. TRIB1 (84 to 372) was diluted for use at 5 μM (with or without 25 μM C/EBPα peptide) with DSF buffer [10 mM Hepes (pH 7.6), 300 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM TCEP]. The protein was incubated in the plate at room temperature for 30 min. SYPRO Orange was then diluted with DSF buffer for use at 5× and was pipetted into each well. The plate was then covered with polymerase chain reaction film and centrifuged for 5 min before being measured on a Roche LightCycler 480 using the default SYPRO Orange protein programme. The data were initially condensed using R version 3.4.3. Data were then analyzed in Microsoft Excel using the CS example DSF Analysis v3.0 template provided by the SGC (60, 61) and Boltzmann fitting in GraphPad Prism 7.

Supplementary Material

Movie S1. Morph between substrate-free (SLE-out) and C/EBPα-bound (SLE-in) structures of TRIB1.

Movie S2. Simulations of the RIB1–C-terminal tail.

Fig. S1. Construct design for crystallization.

Fig. S2. C/EBPα degron electron density.

Fig. S3. Dissociation constant of TRIB1/2-binding C/EBPα.

Fig. S4. Differing C/EBPα-binding potential between TRIB1 and TRIB3.

Fig. S5. Stable regions of C/EBPα degron in complex with TRIB1.

Fig. S6. Displacement of the TRIB1 C-terminal tail from COP1.

Fig. S7. Destabilization of TRIB1 by Y134C mutation.

Fig. S8. PKI screening of TRIB1.

Table S1. DSF data for individual PKIS compounds.

Acknowledgments:

This research was undertaken in part using the MX2 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, part of Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation. We thank the New Zealand synchrotron group for facilitating access to the MX beamlines. This study was supported in part by resources and technical expertise from the Georgia Advanced Computing Resource Center, a partnership between the University of Georgia’s Office of the Vice President for Research and Office of the Vice President for Information Technology. We thank P. Eyers (University of Liverpool) for provision of template to create TRIB2 expression constructs.

Funding: This work was funded by a project grant from the Health Research Council of New Zealand, and P.D.M. received additional support from a Rutherford Discovery Fellowship from the New Zealand government administered by the Royal Society of New Zealand. J.R.C. and H.D.M. were supported by University of Otago Masters and PhD Scholarships, respectively. Funding for N.K. from the NIH (5RO1GM114409) is acknowledged. Z.R. is the recipient of 2017 Innovative and Interdisciplinary Research Grant for Doctoral Students (IIRG). The SGC is a registered charity (number 1097737) that receives funds from AbbVie, Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Eshelman Institute for Innovation, Genome Canada, Innovative Medicines Initiative (European Union/European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations) (ULTRA-DD grant no. 115766), Janssen, Merck & Co., Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), Novartis Pharma AG, Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation, Pfizer, São Paulo Research Foundation–FAPESP (2013/50724-5), Takeda, and Wellcome Trust (106169/ZZ14/Z).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencesignaling.org/cgi/content/full/11/549/eaau0597/DC1

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: The structure of the TRIB1-C/EBPα is deposited in the PDB with accession code 6dc0. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Taylor SS, Kornev AP, Protein kinases: Evolution of dynamic regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36, 65–77 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kung JE, Jura N, Structural basis for the non-catalytic functions of protein kinases. Structure 24, 7–24 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy JM, Mace PD, Eyers PA, Live and let die: Insights into pseudoenzyme mechanisms from structure. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 47, 95–104 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eyers PA, Keeshan K, Kannan N, Tribbles in the 21st century: The evolving roles of tribbles pseudokinases in biology and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 284–298 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mata J, Curado S, Ephrussi A, Rørth P, Tribbles coordinates mitosis and morphogenesis in Drosophila by regulating string/CDC25 proteolysis. Cell 101,511–522 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rørth P, Szabo K, Texido G, The level of C/EBP protein is critical for cell migration during Drosophila oogenesis and is tightly controlled by regulated degradation. Mol. Cell 6, 23–30 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du K, Herzig S, Kulkarni RN, Montminy M, TRB3: A tribbles homolog that inhibits Akt/PKB activation by insulin in liver. Science 300, 1574–1577 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qi L, Heredia JE, Altarejos JY, Screaton R, Goebel N, Niessen S, MacLeod IX, Liew CW, Kulkarni RN, Bain J, Newgard C, Nelson M, Evans RM, Yates J, Montminy M, TRB3 links the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1 to lipid metabolism. Science 312, 1763–1766 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li K, Wang F, Cao W.-b., Lv X.-x., Hua F, Cui B, Yu J.-j., Zhang X-W, Shang S, Liu S-S, Yu J-M, Han M-Z, Huang B, Zhang T.-t., Li X, Jiang J-D, Hu Z.-w., TRIB3 promotes APL progression through stabilization of the oncoprotein PML-RARα and inhibition of p53-mediated senescence. Cancer Cell 31, 697–710.e7 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izrailit J, Berman HK, Datti A, Wrana JL, Reedijk M, High throughput kinase inhibitor screens reveal TRB3 and MAPK-ERK/TGFα pathways as fundamental Notch regulators in breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1714–1719 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoyama T, Kanno Y, Yamazaki Y, Takahara T, Miyata S, Nakamura T, Trib1 links the MEK1/ERK pathway in myeloid leukemogenesis. Blood 116, 2768–2775 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan H, Shuaib A, De Leon DD, Angyal A, Salazar M, Velasco G, Holcombe M, Dower SK, Kiss-Toth E, Competition between members of the tribbles pseudokinase protein family shapes their interactions with mitogen activated protein kinase pathways. Sci. Rep. 6, 32667 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang KL, O’Connor C, Veiga JP, McCarthy TV, Keeshan K, TRIB2 regulates normal and stress-induced thymocyte proliferation. Cell Discov. 2, 15050 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dedhia PH, Keeshan K, Uljon S, Xu L, Vega ME, Shestova O, Zaks-Zilberman M, Romany C, Blacklow SC, Pear WS, Differential ability of Tribbles family members to promote degradation of C/EBPα and induce acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 116, 1321–1328 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satoh T, Kidoya H, Naito H, Yamamoto M, Takemura N, Nakagawa K, Yoshioka Y, Morii E, Takakura N, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Critical role of Trib1 in differentiation of tissue-resident M2-like macrophages. Nature 495, 524–528 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor C, Lohan F, Campos J, Ohlsson E, Salomè M, Forde C, Artschwager R, Liskamp RM, Cahill MR, Kiely PA, Porse B, Keeshan K, The presence of C/EBPα and its degradation are both required for TRIB2-mediated leukaemia. Oncogene 35, 5272–5281 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy JM, Nakatani Y, Jamieson SA, Dai W, Lucet IS, Mace PD, Molecular mechanism of CCAAT-enhancer binding protein recruitment by the TRIB1 pseudokinase. Structure 23, 2111–2121 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramji DP, Foka P, CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: Structure, function and regulation. Biochem. J. 365, 561–575 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Stefano B, Sardina JL, van Oevelen C, Collombet S, Kallin EM, Vicent GP, Lu J, Thieffry D, Beato M, Graf T, C/EBPα poises B cells for rapid reprogramming into induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 506, 235–239 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lourenço AR, Coffer PJ, A tumor suppressor role for C/EBPα in solid tumors: More than fat and blood. Oncogene 36, 5221–5230 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu H, He K, Wang L, Hu J, Gu J, Zhou C, Lu R, Jin Y, Stk40 represses adipogenesis through translational control of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins. J. Cell Sci. 128, 2881–2890 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida A, Kato J.-y., Nakamae I, Yoneda-Kato N, COP1 targets C/EBPα for degradation and induces acute myeloid leukemia via Trib1. Blood 122, 1750–1760 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers JC, Zhang W, Sehmi J, Li X, Wass MN, Van der Harst P, Holm H, Sanna S, Kavousi M, Baumeister SE, Coin LJ, Deng G, Gieger C, Heard-Costa NL, Hottenga J-J, Kühnel B, Kumar V, Lagou V, Liang L, Luan J, Vidal PM, Leach IM, O’Reilly PF, Peden JF, Rahmioglu N, Soininen P, Speliotes EK, Yuan X, Thorleifsson G, Alizadeh BZ, Atwood LD, Borecki IB, Brown MJ, Charoen P, Cucca F, Das D, de Geus EJC, Dixon AL, Döring A, Ehret G, Eyjolfsson GI, Farrall M, Forouhi NG, Friedrich N, Goessling W, Gudbjartsson DF, Harris TB, Hartikainen A-L, Heath S, Hirschfield GM, Hofman A, Homuth G, Hyppönen E, Janssen HLA, Johnson T, Kangas AJ, Kema IP, Kühn JP, Lai S, Lathrop M, Lerch MM, Li Y, Liang TJ, Lin J-P, Loos RJF, Martin NG, Moffatt MF, Montgomery GW, Munroe PB, Musunuru K, Nakamura Y, O’Donnell CJ, Olafsson I, Penninx BW, Pouta A, Prins BP, Prokopenko I, Puls R, Ruokonen A, Savolainen MJ, Schlessinger D, Schouten JNL, Seedorf U, Sen-Chowdhry S, Siminovitch KA, Smit JH, Spector TD, Tan W, Teslovich TM, Tukiainen T, Uitterlinden AG, Van der Klauw MM, Vasan RS, Wallace C, Wallaschofski H, Wichmann H-E, Willemsen G, Würtz P, Xu C, Yerges-Armstrong LM; Alcohol Genome-wide Association (AlcGen) Consortium; Diabetes Genetics Replication, Meta-analyses (DIAGRAM+) Study; Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium; Global Lipids Genetics Consortium; Genetics of Liver Disease (GOLD) Consortium; International Consortium for Blood Pressure (ICBP-GWAS); Meta-analyses of Glucose, Insulin-Related Traits Consortium (MAGIC), Abecasis GR, Ahmadi KR, Boomsma DI, Caulfield M, Cookson WO, van Duijn CM, Froguel P, Matsuda K, McCarthy MI, Meisinger C, Mooser V, Pietiläinen KH, Schumann G, Snieder H, Sternberg MJE, Stolk RP, Thomas HC, Thorsteinsdottir U, Uda M, Waeber G, Wareham NJ, Waterworth AM, Watkins H, Whitfield JB, Witteman JCM, Wolffenbuttel BHR, Fox CS, Ala-Korpela M, Stefansson K, Vollenweider P, Völzke H, Schadt EE, Scott J, Järvelin M-R, Elliott P, Kooner JS, Genome-wide association study identifies loci influencing concentrations of liver enzymes in plasma. Nat. Genet. 43, 1131–1138 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kathiresan S, Melander O, Guiducci C, Surti A, Burtt NP, Rieder MJ, Cooper GM, Roos C, Voight BF, Havulinna AS, Wahlstrand B, Hedner T, Corella D, Tai AS, Ordovas JM, Berglund G, Vartiainen E, Jousilahti P, Hedblad B, Taskinen M-R, Newton-Cheh C, Salomaa V, Peltonen L, Groop L, Altshuler DM, Orho-Melander MM, Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat. Genet. 40, 189–197 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauer RC, Sasaki M, Cohen DM, Cui J, Smith MA, Yenilmez BO, Steger DJ, Rader DJ, Tribbles-1 regulates hepatic lipogenesis through posttranscriptional regulation of C/EBPα. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 3809–3818 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uljon S, Xu X, Durzynska I, Stein S, Adelmant G, Marto JA, Pear WS, Blacklow SC, Structural basis for substrate selectivity of the E3 ligase COP1. Structure 24, 687–696 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishizuka Y, Nakayama K, Ogawa A, Makishima S, Boonvisut S, Hirao A, Iwasaki Y, Yada TT, Yanagisawa Y, Miyashita H, Takahashi M, Iwamoto S; Jichi Medical University Promotion Team of a Large-Scale Human Genome Bank for All over Japan, TRIB1 downregulates hepatic lipogenesis and glycogenesis via multiple molecular interactions. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 52, 145–158 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X, Liu X, Wang G, Zhu X, Qu X, Li X, Yang Y, Peng L, Li C, Li P, Huang W, Ma Q, Cao C, Non-receptor tyrosine kinases c-Abl and Arg regulate the activity of C/EBPβ. J. Mol. Biol. 391, 729–743 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shuman JD, Sebastian T, Kaldis P, Copeland TD, Zhu S, Smart RC, Johnson PF, Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of C/EBPβ mediates oncogenic cooperativity between C/EBPβ and H-RasV12. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 7380–7391 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durzynska I, Xu X, Adelmant G, Ficarro SB, Marto JA, Sliz P, Uljon S, Blacklow SC, STK40 is a pseudokinase that binds the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1. Structure 25, 287–294 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey FP, Byrne DP, Oruganty K, Eyers CE, Novotny CJ, Shokat KM, Kannan N, Eyers PA, The Tribbles 2 (TRB2) pseudokinase binds to ATP and autophosphorylates in a metal-independent manner. Biochem. J. 467, 47–62 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foulkes DM, Byrne DP, Yeung W, Shrestha S, Bailey FP, Ferries S, Eyers CE, Keeshan K, Wells C, Drewry DH, Zuercher WJ, Kannan N, Eyers PA, Covalent inhibitors of EGFR family protein kinases induce degradation of human Tribbles 2 (TRIB2) pseudokinase in cancer cells. Sci. Signal. 11, eaat7951 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy JM, Zhang Q, Young SN, Reese ML, Bailey FP, Eyers PA, Ungureanu D, Hammaren E, Silvennoinen O, Varghese LN, Chen K, Tripaydonis A, Jura N, Fukuda K, Qin J, Nimchuk Z, Mudgett MB, Elowe S, Gee CL, Liu L, Daly RJ, Manning G, Babon JJ, Lucet IS, A robust methodology to subclassify pseudokinases based on their nucleotide-binding properties. Biochem. J. 457, 323–334 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elkins JM, Fedele V, Szklarz M, Abdul Azeez KR, Salah E, Mikolajczyk J, Romanov S, Sepetov N, Huang X-P, Roth BL, Al Haj Zen A, Fourches D, Muratov E, Tropsha A, Morris J, Teicher BA, Kunkel M, Polley E, Lackey KE, Atkinson FL, Overington JP, Bamborough P, Müller S, Price DJ, Willson TM, Drewry DH, Knapp S, Zuercher WJ, Comprehensive characterization of the Published Kinase Inhibitor Set. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 95–103 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rheault TR, Caferro TR, Dickerson SH, Donaldson KH, Gaul MD, Goetz AS, Mullin RJ, McDonald OB, Petrov KG, Rusnak DW, Shewchuk LM, Spehar GM, Truesdale AT, Vanderwall DE, Wood ER, Uehling DE, Thienopyrimidine-based dual EGFR/ErbB-2 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 817–820 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyazaki Y, Tang J, Maeda Y, Nakano M, Wang L, Nolte RT, Sato H, Sugai M, Okamoto Y, Truesdale AT, Hassler DF, Nartey EN, Patrick DR, Ho ML, Ozawa K, Orally active 4-amino-5-diarylurea-furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives as anti-angiogenic agent inhibiting VEGFR2 and Tie-2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17, 1773–1778 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasegawa M, Nishigaki N, Washio Y, Kano K, Harris PA, Sato H, Mori I, West RI, Shibahara M, Toyoda H, Wang L, Nolte RT, Veal JM, Cheung M, Discovery of novel benzimidazoles as potent inhibitors of TIE-2 and VEGFR-2 tyrosine kinase receptors. J. Med. Chem. 50, 4453–4470 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nerlov C, C/EBPα mutations in acute myeloid leukaemias. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 394–400 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pal R, Janz M, Galson DL, Gries M, Li S, Jöhrens K, Anagnostopoulos I, Dörken B, Mapara MY, Borghesi L, Kardava L, Roodman GD, Milcarek C, Lentzsch S, C/EBPβ regulates transcription factors critical for proliferation and survival of multiple myeloma cells. Blood 114, 3890–3898 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guerzoni C, Bardini M, Mariani SA, Ferrari-Amorotti G, Neviani P, Panno ML, Zhang Y, Martinez R, Perrotti D, Calabretta B, Inducible activation of CEBPB, a gene negatively regulated by BCR/ABL, inhibits proliferation and promotes differentiation of BCR/ABL-expressing cells. Blood 107, 4080–4089 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu G, Zhang Q, Huang Y, Song J, Tomaino R, Ehrenberger T, Lim E, Liu W, Bronson RT, Bowden M, Brock J, Krop I, Dillon DA, Gygi SP, Mills GB, Richardson AL, Signoretti S, Yaffe MB, Kaelin WG Jr., Phosphorylation of ETS1 by Src family kinases prevents its recognition by the COP1 tumor suppressor. Cancer Cell 26, 222–234 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Filipčik P, Curry JR, Mace PD, When worlds collide—Mechanisms at the interface between phosphorylation and ubiquitination. J. Mol. Biol. 429, 1097–1113 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mùszáros B, Kumar M, Gibson TJ, Uyar B, Dosztányi Z, Degrons in cancer. Sci. Signal. 10, eaak9982 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dhawan NS, Scopton AP, Dar AC, Small molecule stabilization of the KSR inactive state antagonizes oncogenic Ras signalling. Nature 537, 112–116 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xie T, Lim SM, Westover KD, Dodge ME, Ercan D, Ficarro SB, Udayakumar D, Gurbani D, Tae HS, Riddle SM, Sim T, Marto JA, Jänne PA, Crews CM, Gray NS, Pharmacological targeting of the pseudokinase Her3. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 1006–1012 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kabsch W, XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Storoni LC, McCoy AJ, Read RJ, Likelihood-enhanced fast rotation functions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 432–438 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emsley P, Cowtan K, Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murshudov GN, Skubák P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA, REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 355–367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eswar N, Webb B, Marti-Renom MA, Madhusudhan MS, Eramian D, Shen M.-y., Pieper U, Sali A, Comparative protein structure modeling using Modeller. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 5, Unit-5.6 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, Lindahl E, GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1-2, 19–25 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Palmo K, Maragakis P, Klepeis JL, Dror RO, Shaw DE, Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins 78, 1950–1958 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Páll S, Hess B, A flexible algorithm for calculating pair interactions on SIMD architectures. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 2641–2650 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LG, A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bussi G, Donadio D, Parrinello M, Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McClendon CL, Hua L, Barreiro A, Jacobson MP, Comparing conformational ensembles using the Kullback-Leibler divergence expansion. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 2115–2126 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keller S, Vargas C, Zhao H, Piszczek G, Brautigam CA, Schuck P, High-precision isothermal titration calorimetry with automated peak-shape analysis. Anal. Chem. 84, 5066–5073 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Houtman JCD, Brown PH, Bowden B, Yamaguchi H, Appella E, Samelson LE, Schuck P, Studying multisite binary and ternary protein interactions by global analysis of isothermal titration calorimetry data in SEDPHAT: Application to adaptor protein complexes in cell signaling. Protein Sci. 16, 30–42 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vedadi M, Niesen FH, Allali-Hassani A, Fedorov OY, Finerty PJ Jr., Wasney GA, Yeung R, Arrowsmith C, Ball LJ, Berglund H, Hui R, Marsden BD, Nordlund P, Sundstrom M, Weigelt J, Edwards AM, Chemical screening methods to identify ligands that promote protein stability, protein crystallization, and structure determination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15835–15840 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M, The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2212–2221 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie S1. Morph between substrate-free (SLE-out) and C/EBPα-bound (SLE-in) structures of TRIB1.

Movie S2. Simulations of the RIB1–C-terminal tail.

Fig. S1. Construct design for crystallization.

Fig. S2. C/EBPα degron electron density.

Fig. S3. Dissociation constant of TRIB1/2-binding C/EBPα.

Fig. S4. Differing C/EBPα-binding potential between TRIB1 and TRIB3.

Fig. S5. Stable regions of C/EBPα degron in complex with TRIB1.

Fig. S6. Displacement of the TRIB1 C-terminal tail from COP1.

Fig. S7. Destabilization of TRIB1 by Y134C mutation.

Fig. S8. PKI screening of TRIB1.

Table S1. DSF data for individual PKIS compounds.