Abstract

Etioplasts developed in angiosperm cotyledon cells in darkness rapidly differentiate into chloroplasts with illumination. This process involves dynamic transformation of internal membrane structures from the prolamellar bodies (PLBs) and prothylakoids (PTs) in etioplasts to thylakoid membranes in chloroplasts. Although two galactolipids, monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), are predominant lipid constituents of membranes in both etioplasts and chloroplasts, their roles in the structural and functional transformation of internal membranes during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation are unknown. We previously reported that a 36% loss of MGDG by an artificial microRNA targeting major MGDG synthase (amiR-MGD1) only slightly affected PLB structures but strongly impaired PT formation and protochlorophyllide biosynthesis. Meanwhile, strong DGDG deficiency in a DGDG synthase mutant (dgd1) disordered the PLB lattice structure in addition to impaired PT development and protochlorophyllide biosynthesis. In this study, thylakoid biogenesis after PLB disassembly with illumination was strongly perturbed by amiR-MGD1. The amiR-MGD1 expression impaired the accumulation of Chl and the major light-harvesting complex II protein (LHCB1), which may inhibit rapid transformation from disassembled PLBs to the thylakoid membrane. As did amiR-MGD1 expression, dgd1 mutation impaired the accumulation of Chl and LHCB1 during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation. Furthermore, unlike in amiR-MGD1 seedlings, in dgd1 seedlings, disassembly of PLBs after illumination was retarded. Because DGDG but not MGDG prefers to form the bilayer lipid phase in membranes, the MGDG-to-DGDG ratio may strongly affect the transformation of PLBs to the thylakoid membrane during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation.

Keywords: Chloroplast, Digalactosyldiacylglycerol, Etioplast, Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol, Prolamellar body, Thylakoid membrane

Introduction

Biogenesis of the thylakoid membrane, the site of photochemical reactions, in chloroplasts requires coordinated assembly of proteins, cofactors and lipids. Glycerolipids function as building blocks of the thylakoid membrane and provide the lipid bilayer matrix for protein–pigment complexes and hydrophobic cofactors. In the thylakoid membrane, two uncharged galactolipids, monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), account for approximately 50% and 30%, respectively, of the total membrane lipids (Dorne et�al. 1990). Despite only one galactose difference in their polar head groups, MGDG and DGDG show different phase behaviors in aqueous media. DGDG can self-assemble into lamellar bilayers in mixtures with water, whereas MGDG is a nonbilayer-forming lipid and forms an inverse hexagonal phase in aqueous media (Shipley et�al. 1973). The ratio of bilayer-forming DGDG and nonbilayer-forming MGDG largely affects the phase behavior of lipid bilayers and may be involved in the organization of thylakoid membrane structures (Dem� et�al. 2014).

In plant cells, MGDG is synthesized from diacylglycerol (DAG) and UDP-galactose by MGDG synthase (Benning and Ohta 2005). A portion of MGDG is further galactosylated with UDP-galactose by DGDG synthase to yield DGDG. The Arabidopsis thaliana genome has three MGDG synthase genes (MGD1, MGD2 and MGD3) and two DGDG synthase genes (DGD1 and DGD2). MGD1 in the inner envelope and DGD1 in the outer envelope of plastids synthesize the bulk of MGDG and DGDG, respectively, in photosynthetic tissues. The alternative pathway by MGD2-MGD3 and DGD2, which are all localized to the outer envelope of plastids, particularly contributes to DGDG accumulation under phosphate starvation (Kobayashi et�al. 2009b). In addition, SENSITIVE TO FREEZING 2, which transfers a galactose residue from MGDG to a second galactolipid to yield oligogalactolipids, is involved in galactolipid biosynthesis specifically under freezing conditions (Moellering et�al. 2010).

DAGs used for galactolipid biosynthesis are derived from two different pathways (Browse and Somerville 1991, Ohlrogge and Browse 1995). The plastid pathway produces DAGs entirely within plastids, whereas the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) pathway first produces phospholipids in ER, then DAGs metabolized from the phospholipids are used in plastids. In both pathways, fatty acids (FAs) are synthesized in conjugation with acyl carrier protein (ACP) within plastids. In the plastid pathway, 16:0-ACP and 18:1-ACP, the latter made from 18:0-ACP by stearoyl-ACP desaturase (SAD) in plastids, are directly used for glycerolipid biosynthesis. Meanwhile, a portion of these acyl-ACPs is hydrolyzed by plastid thioesterases to free FAs, exported from plastids, then used for the ER pathway after conjugation with CoA (Li-Beisson et�al. 2013). DAGs from the plastid pathway contain C-18 FAs at the sn-1 position and C-16 FAs at the sn-2 position of the glycerol backbone. In contrast, DAGs from the ER pathway contain C-18 or C-16 FAs at the sn-1 position and C-18 FAs at the sn-2 position. C-18 FAs of galactolipids are mostly unsaturated to linolenic acids (18:3) in the plastid or ER pathway. Specifically in MGDG from the plastid pathway, C-16 FAs at the sn-2 position are unsaturated to 16:3. Molecular lipid species analyses indicate that in Arabidopsis, half of MGDG in chloroplasts is synthesized via the plastid pathway, whereas much of DGDG is derived from the ER pathway (Browse and Somerville 1991, Ohlrogge and Browse 1995).

The thylakoid membrane is characterized by its high protein density: 70–80% of the membrane area is occupied by proteins (Kirchhoff et�al. 2002). Thus, integration of protein complexes into the lipid bilayer matrix is a crucial process for thylakoid membrane biogenesis. The light-harvesting complex proteins (LHCPs), in particular the major light-harvesting complex II (LHCII), are highly abundant in the thylakoid membrane and concentrated in the grana region (Pribil et�al. 2014). In vitro analysis revealed that despite the nonbilayer-forming nature of MGDG, this lipid can form ordered lamellar structures in the presence of LHCII, which indicates the importance of the MGDG–LHCII interaction for lipid phase behavior in the thylakoid membrane (Simidjiev et�al. 2000). Mutant analysis of the ALBINO3 protein, which mediates insertion of LHCPs into the thylakoid membrane, in Arabidopsis suggests that integration of LHCPs into the membrane is essential for the development of the thylakoid membrane and grana formation (Sundberg et�al. 1997). PSI and PSII are also major protein–cofactor complexes in the thylakoid membrane. Disruption of PSI or PSII strongly affects the structure of the thylakoid membrane in plant chloroplasts. In particular, PSI is required for the formation of stroma lamellae, whereas PSII is more important for the organization of grana stacks (Pribil et�al. 2014).

In chloroplasts, the major portion of total Chl is bound to LHCPs and is required for the assembly of the complexes. Many mutants deficient in Chl biosynthesis showed severely impaired thylakoid biogenesis and grana stacking, with decreased or no accumulation of LHCPs (Frick et�al. 2003, Pontier et�al. 2007, Bang et�al. 2008, Apitz et�al. 2014). Moreover, a Chl b-deficient Arabidopsis mutant showed decreased LHCII accumulation and loss of LHCII trimers, which resulted in decreased grana stacking of the thylakoid membrane (Kim et�al. 2009). These data indicate that Chl is required for the accumulation of LHCPs and is involved in thylakoid membrane biogenesis. Chl biosynthesis is also essential for the accumulation of D1, the core protein of PSII, and the assembly of PSII (M�ller and Eichacker 1999).

During germination of angiosperms under light, undifferentiated plastids in cotyledon mesophyll cells differentiate into chloroplasts with the thylakoid membrane. However, in the absence of light, proplastids differentiate into etioplasts with unique lattice membrane structures called prolamellar bodies (PLBs) and lamellar prothylakoid (PTs) membranes (Solymosi and Schoefs 2010). PLBs accumulate a Chl precursor, protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) a, and light-dependent NADPH:Pchlide oxidoreductase (LPOR) in the lipid bilayer matrix. Although some photosynthesis-associated proteins, such as subunits of ATP synthase and the Cytb6f complex, already exist in etioplasts (Blomqvist et�al. 2008), LHCPs are almost absent and, if present, are not yet inserted in the membrane (Kuttkat et�al. 1997, M�ller and Eichacker 1999). PSI and PSII proteins also show minor abundance in etioplasts and are not assembled into mature complexes (M�ller and Eichacker 1999).

The lipid composition of PLBs is similar to that of the thylakoid membrane: in PLBs of wheat etioplasts, MGDG and DGDG account for approximately 50% and 30%, respectively, of total glycerolipids (Selstam and Sandelius 1984). Expression of a dexamethasone (DEX)-inducible artificial microRNA targeting MGD1 (amiR-MGD1) in dark-grown Arabidopsis seedlings reduced MGD1 mRNA level by 70% as compared with the control, which resulted in 36% loss of MGDG without affecting DGDG content (Fujii et�al. 2017). Although the loss of MGDG in etioplasts only slightly changed the lattice structure of PLBs, it strongly impaired the elongation of PTs and the formation and oligomerization of Pchlide–LPOR complexes in membranes. Moreover, in the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway, three sequential membrane-associated processes from the Mg-protoporphyrin IX formation to Pchlide synthesis, particularly the monomethyl esterification of Mg-protoporphyrin IX, were severely inhibited by loss of MGDG in etioplasts. We previously investigated the role of DGDG in etioplasts (Fujii et�al. 2018) by analyzing a knockout mutant of DGD1 (dgd1; D�rmann et�al. 1995). In the dark-grown dgd1 mutant, DGDG content was reduced by 80% as compared with the wild type and, as in amiR-MGD1 seedlings, membrane processes of Pchlide biosynthesis were impaired. Furthermore, the lattice structure of PLBs was strongly disordered and PTs were severely underdeveloped in mutant etioplasts. These data demonstrate the essential roles of galactolipids in the formation of internal membranes and membrane-associated processes in etioplasts.

Once the etiolated seedlings are exposed to light, most Pchlide molecules in PLBs are immediately converted to chlorophyllide by LPOR and then to Chl via some enzymatic processes (Schoefs and Bertrand 2000, Schoefs 2001). At the same time, light triggers de novo Chl biosynthesis and the expression of photosynthetic proteins to establish photosynthetic systems. In morphology, PLBs and PTs are directly transformed to the thylakoid membrane and etioplasts differentiate into chloroplasts (Kowalewska et�al. 2016). We previously reported that MGDG biosynthesis is essential for the initiation of chloroplast biogenesis in light-grown seedlings (Kobayashi et�al. 2007, Kobayashi et�al. 2013, Fujii et�al. 2014). However, the roles of these galactolipids during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation remain unclear. To reveal how the deficiency of galactolipid biosynthesis affects thylakoid biogenesis from PLBs during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation, we examined dark-grown amiR-MGD1 and dgd1 seedlings after illumination.

Results

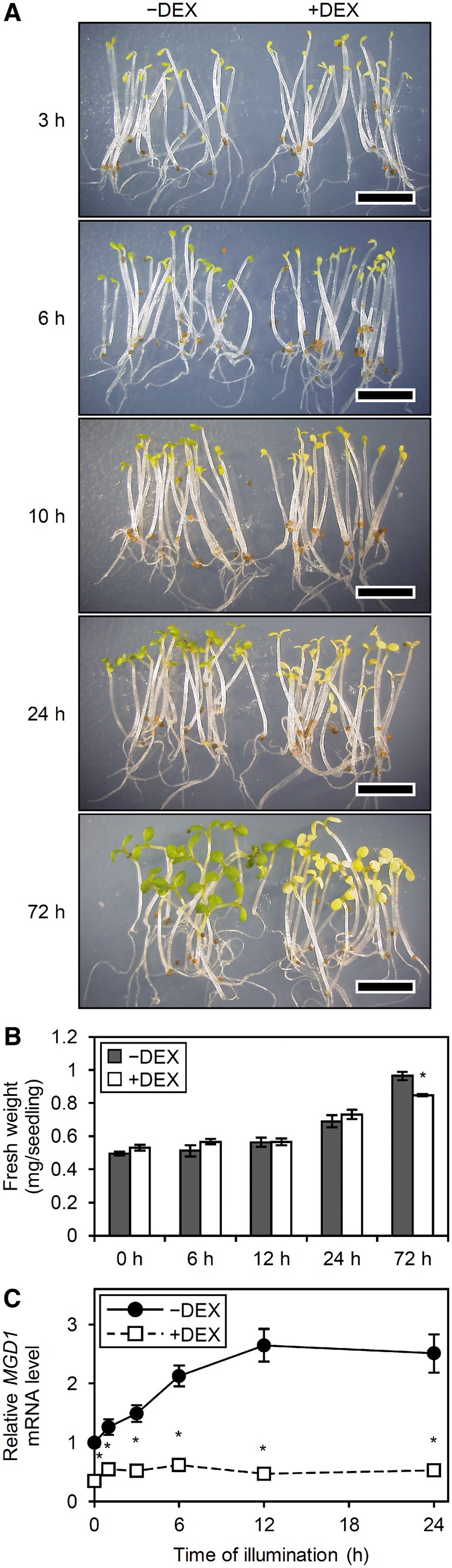

MGD1 suppression impairs greening after dark growth

To assess how MGD1 suppression affects conversion from etioplasts to chloroplasts on illumination, we grew a strong line (L4w) of amiR-MGD1 transgenic plants (Fujii et�al. 2017) in complete darkness for 4 d in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX and then illuminated them with continuous white light. In +DEX seedlings, the greening of cotyledons was strongly impaired compared with the –DEX control (Fig.�1A), although fresh weight was similar between +DEX and –DEX seedlings before and at 24 h of illumination (Fig.�1B). After 72-h illumination, +DEX seedlings had lower fresh weight than the –DEX control, with cotyledon greening remained strongly impaired.

Fig. 1.

Greening of dark-grown amiR-MGD1 seedlings after illumination. Plants were grown for 4 d in the dark and then illuminated for indicated hours in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX. (A) Phenotype and (B) fresh weight of amiR-MGD1 seedlings. Bars in (A) = 5.0 mm. Data in (B) are means � SE from three (0 h) or four (6, 12, 24, 72 h) independent experiments. (C) MGD1 mRNA levels presented as fold difference from the −DEX control at 0 h of illumination after normalization to the control gene ACTIN8. Data are means � SE from 13 (0 ) or three (1, 3, 6, 12, 24 h) independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant difference from the −DEX control (P < 0.05, Student’s t-test).

To ascertain whether MGD1 expression during illumination was suppressed by DEX treatment in the amiR-MGD1 line, we determined MGD1 mRNA levels by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis (Fig.�1C). As we previously reported (Fujii et�al. 2017), MGD1 mRNA level was approximately 30% of −DEX control levels before illumination. In −DEX seedlings, MGD1 level increased gradually with illumination and reached 2.5-fold of the initial level after 12 h of illumination. However, in +DEX seedlings, MGD1 mRNA level did not notably increase in response to illumination. Thus, MGD1 mRNA level in +DEX seedlings was only approximately 20% of the −DEX levels after 12 h of illumination. We also examined the mRNA levels of MGD2, MGD3, DGD1 and DGD2 during the greening process of amiR-MGD1 plants (see Supplementary Fig. S1). In +DEX seedlings, MGD2 mRNA level decreased compared with the −DEX control after 12-h illumination, whereas those of MGD3, DGD1 and DGD2 showed no remarkable difference between +DEX and –DEX seedlings.

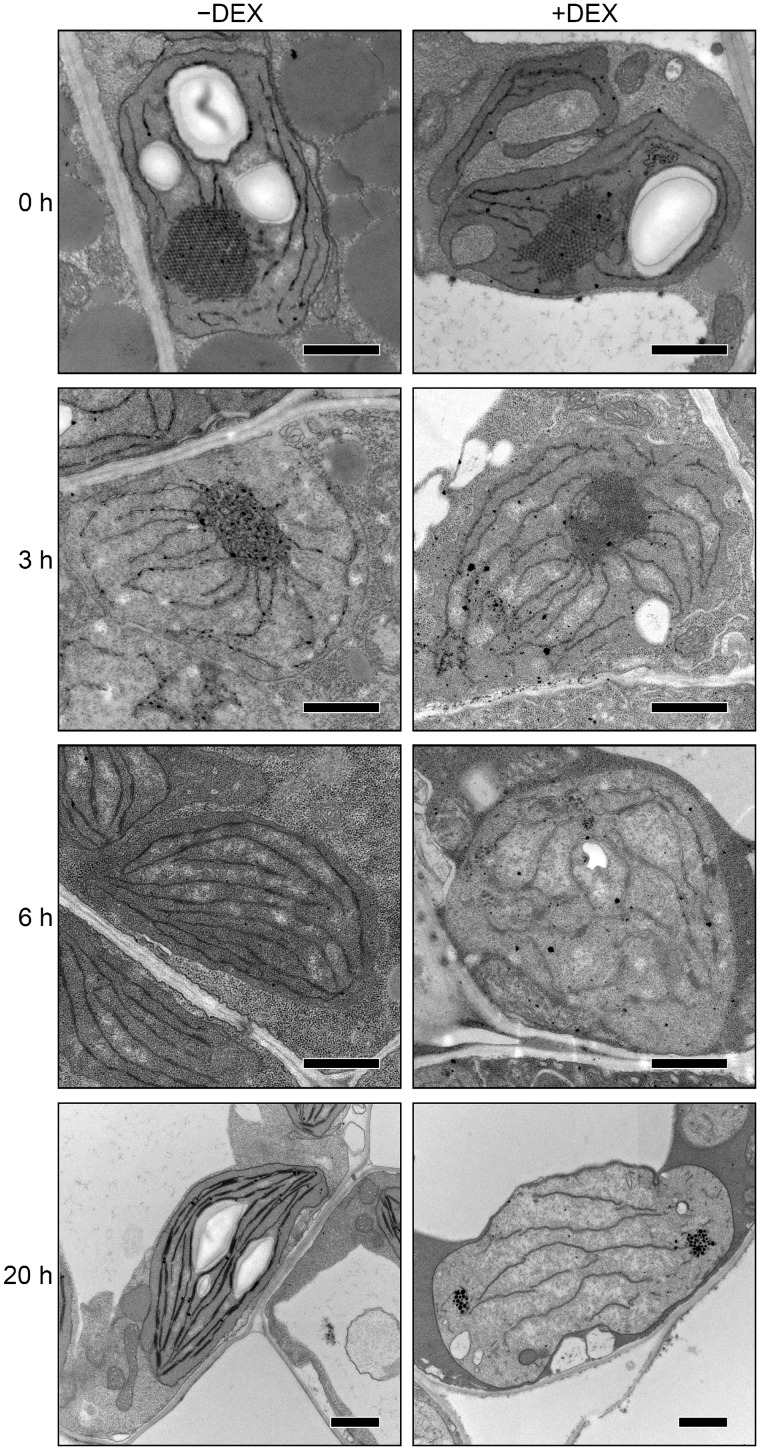

MGD1 suppression strongly impairs thylakoid membrane biogenesis with illumination

We next analyzed the ultrastructure of plastids in cotyledons after illumination for 0, 3, 6 and 20 h (Fig.�2 and Supplementary Fig S2). In etioplasts of −DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings grown in the dark (0 h), regular lattice PLB structures were observed with PTs connected to the PLBs. After 3-h illumination, the crystalline structure of PLBs was disrupted and transformed into aggregates of short membranes. Most plastids had round shapes. After 6-h illumination, PLB remnants were no longer detected in all plastids observed in −DEX seedlings. Instead, lamellar thylakoid membranes had developed and frequently formed short stacks of two or three membranes. The plastids had a spindle or lens-like shape, with thylakoid membranes oriented toward each apex. After 20-h illumination, the thylakoid membrane networks were extended and grana stacks were markedly developed in cotyledon plastids of −DEX seedlings. Starch granules were formed between thylakoid membranes in these plastids.

Fig. 2.

Changes in ultrastructure of cotyledon plastids during greening of dark-grown amiR-MGD1 seedlings. Plants were grown for 4 d in the dark and then illuminated for indicated hours in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX. Bars = 1.0 μm.

We previously reported that +DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings grown in the dark showed reduced PT development and slightly disordered PLB structures in etioplasts (Fujii et�al. 2017; Fig.�2). After 3-h illumination of +DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings, the PLB lattice membranes were transformed into irregular membrane aggregates as in the −DEX control. After 6-h illumination, PLB remnants were scarcely observed in plastids of +DEX cotyledons as in the −DEX control. However, unlike in −DEX plastids, thylakoid membranes were underdeveloped and did not align horizontally in many +DEX plastids, although some plastids showed thylakoid-like membrane structures with immature grana stacks (see Supplementary Fig. S2A). After 20-h illumination, the development of internal membranes was strongly perturbed and only a few fragmented stromal lamellae were observed. In addition, high electron-dense particles similar to plastoglobuli were often observed in the stromal region (Fig.�2 and Supplementary Fig. S2B). Plastids in +DEX cotyledons had a distorted circular outline and did not contain starch granules inside.

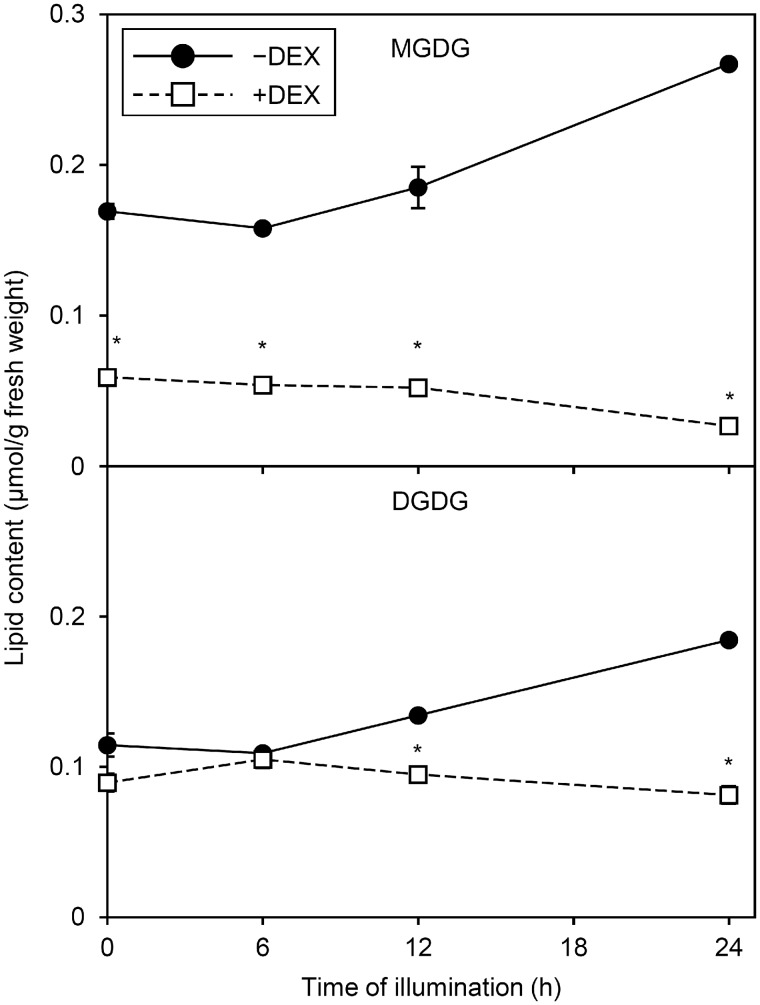

Galactolipid biosynthesis during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation is impaired by disruption of MGD1

To examine whether the morphological changes in internal membranes of plastids during the greening process were linked to changes in galactolipid content, we determined the amount of MGDG and DGDG in −DEX and +DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings before and after illumination. In −DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings, although the proportion of MGDG and DGDG in total membrane lipids slightly increased after 6-h illumination (Supplementary Fig. S3), absolute MGDG and DGDG content per fresh weight was not significantly increased (Fig.�3). Similar trends continued until 12-h illumination. At 24 h after illumination, −DEX seedlings showed a significant increase in MGDG and DGDG content. In +DEX seedlings grown in the dark (0 h), MGDG but not DGDG content substantially decreased as compared with the −DEX control, which agreed with a previous report (Fujii et�al. 2017). Moreover, under the +DEX condition, both MGDG and DGDG content decreased with illumination: after 24-h illumination, MGDG and DGDG content in +DEX seedlings was only 10% and 44%, respectively, of the −DEX control levels.

Fig. 3.

Changes in MGDG and DGDG content during greening of dark-grown amiR-MGD1 seedlings. Seedlings were illuminated for indicated hours after 4-d growth in the dark in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX. Data are means � SE from three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant difference from the −DEX control (P < 0.05, Student’s t-test).

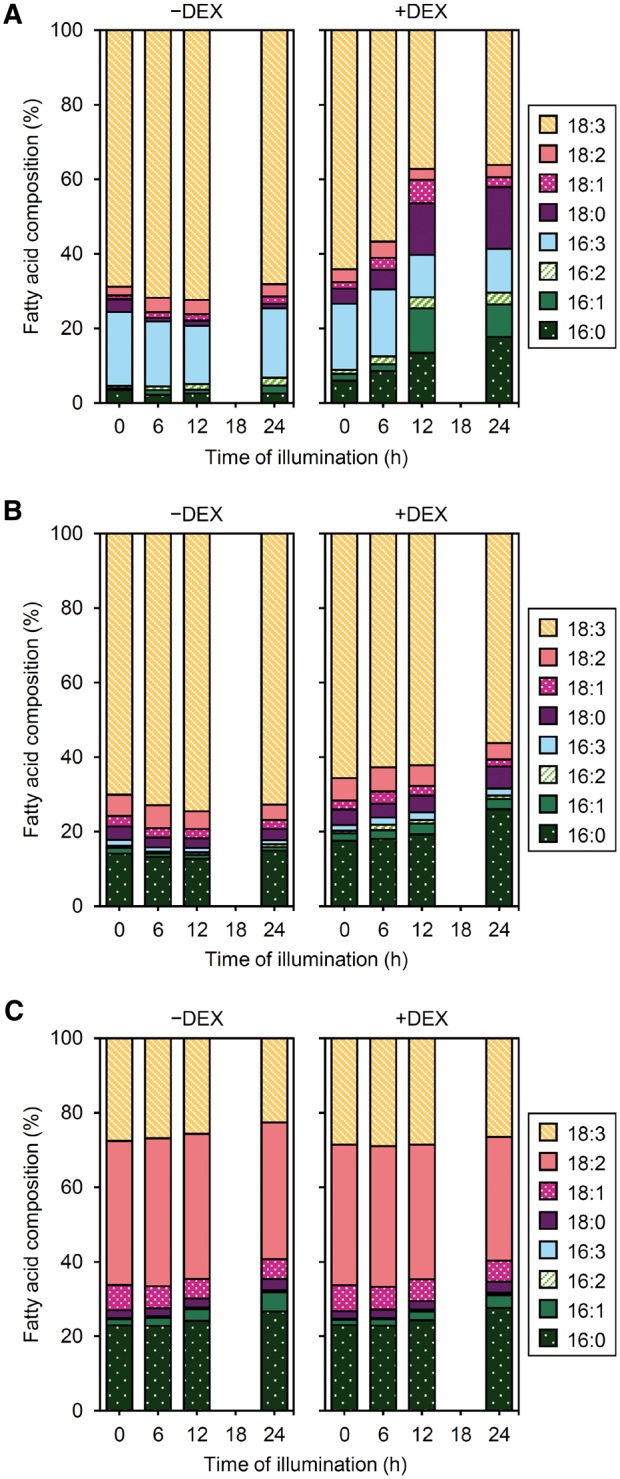

We then analyzed the FA composition of galactolipids before and after illumination. As we reported previously (Fujii et�al. 2017), before illumination, the FA composition of MGDG and DGDG did not notably differ between +DEX and −DEX seedlings (Fig.�4). After illumination, −DEX seedlings showed only small changes in FA composition of MGDG and DGDG: the proportion of 16:3 in MGDG was slightly decreased with illumination for 12 h but recovered after 24 h, and that of 18:3 in DGDG slightly increased, with decreased proportions of 18:2 and 16:0. In contrast, in +DEX seedlings, the proportions of 16:3 and 18:3 in MGDG remarkably decreased and those of 16:1 and 18: 0 increased during 6 to 12 h of illumination (Fig.�4A). In addition, the proportion of 16:0 in MGDG gradually increased during illumination. Also, the absolute amounts of 16:0, 16:1 and 18:0 in MGDG increased from 6 to 12 h of illumination but decreased later with a decrease in total MGDG content (see Supplementary Fig. S4A). In DGDG, the proportion of 18:3 decreased and that of 16:0 increased in +DEX seedlings during illumination (Fig.�4B). Similar patterns were observed for absolute amounts (see Supplementary Fig. S4B). Meanwhile, the composition of total FAs from other membrane lipids was not notably changed by DEX treatment before and after illumination (Fig.�4C). These results suggest that MGD1 suppression specifically affected FA metabolism of galactolipids during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation.

Fig. 4.

Changes in FA composition of galactolipids during greening of dark-grown amiR-MGD1 seedlings. FA composition of (A) MGDG, (B) DGDG and (C) other membrane lipids. Seedlings were illuminated for indicated hours after 4-d growth in the dark in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX. Data are means from three independent experiments.

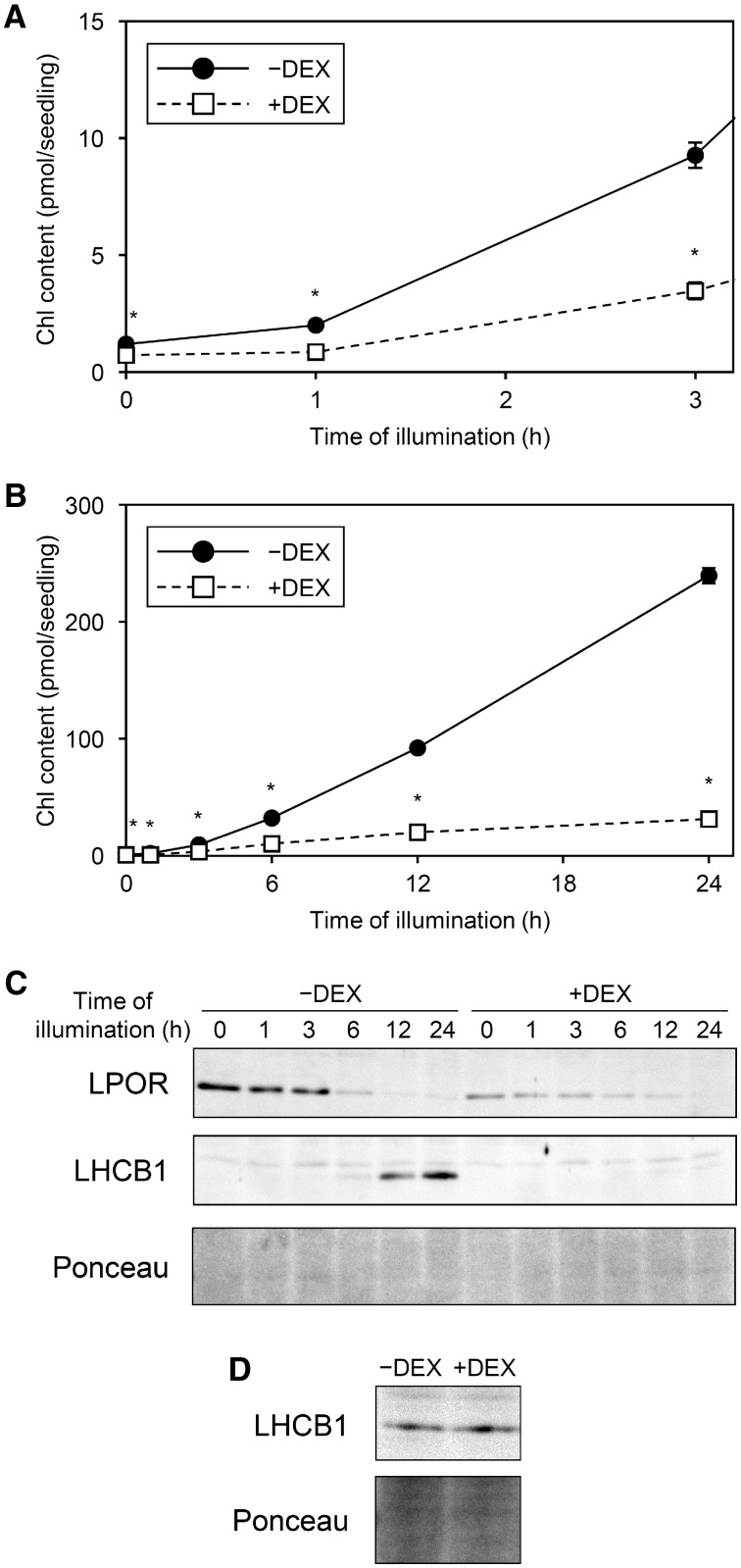

MGD1 suppression affects Chl and membrane protein levels during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation

MGD1 suppression by amiR-MGD1 impaired Pchlide accumulation in dark-grown seedlings (Fujii et�al. 2017). Reflecting the decreased Pchlide content by DEX treatment, the amount of Chl at 1 h after illumination, which would mainly originate from Pchlide accumulated in the dark, was lower in +DEX amiR-MGD1 than −DEX control seedlings (Fig.�5A). After 3-h illumination, Chl content rapidly increased in −DEX control plants but not much in +DEX seedlings. The accumulation of Chl was continuously impaired in +DEX seedlings during illumination; indeed, Chl level in +DEX plants was only 13% of the −DEX control at 24 h after illumination (Fig.�5B), consistent with the strong impairment of cotyledon greening in +DEX seedlings (Fig.�1). To confirm the relationship between the MGD1 suppression level and the impaired Chl accumulation, we also analyzed Chl content in a weak amiR-MGD1 line (L4g), where MGD1 mRNA level decreased to approximately 50% of the control levels (see Supplementary Fig. S5A). The accumulation rate of Chl in +DEX L4g seedlings was similar to that in the −DEX control until 12-h illumination, but diminished at 24 h (see Supplementary Fig. S5B). We also confirmed that DEX treatment itself had no effect on Chl accumulation in wild-type Arabidopsis seedlings (Landsberg erecta) illuminated for 24 h (see Supplementary Fig. S5C). Thus, the diminished Chl accumulation in +DEX L4g seedlings would result from the partial MGD1 suppression.

Fig. 5.

Changes in Chl and protein levels during greening of dark-grown amiR-MGD1 seedlings. Seedlings were illuminated for indicated hours after 4-d growth in the dark in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX. (A, B) Chl content per seedling. The amount of protochlorophyllide (Fujii et al. 2017, www.plantphysiol.org. Copyright American Society of Plant Biologists) is shown for 0 h instead of Chl amount. (A) is an enlarged view of (B) within 3 h of illumination. Data are mean � SE from 12 (0, 1, 3, 6, 12 h) or 6 (24 h) independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant difference from −DEX control (P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). (C) Time course immunoblot analysis of LPOR and LHCB1 proteins and (D) detection of LHCB1 proteins in seedlings illuminated for 3 h. In (D), 50 μg of total protein was used to detect faint LHCB1 signals from 3-h illuminated samples, whereas 10 μg of total protein was used for the time course analysis in (C). Unspecific bands were constantly observed above the LHCB1 bands. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Ponceau-stained proteins were shown as a loading control.

We previously reported that MGD1 suppression by amiR-MGD1 did not decrease the amount of LPOR protein, which determines the size of PLBs, in the dark (Fujii et�al. 2017). However, in this study, we continually found lower LPOR level in +DEX than −DEX control seedlings in the dark (Fig.�5C). Because the signal intensities of proteins in immunoblot analysis often include a large deviation, the small difference in LPOR levels between dark-grown +DEX and −DEX plants might have been masked in the previous study. In the −DEX control, LPOR level gradually decreased with illumination but remained detectable at 24 h after illumination. However, in +DEX seedlings, LPOR level decreased to almost undetectable after 24-h illumination.

LHCII plays a crucial role in thylakoid membrane biogenesis and maintenance (Pribil et�al. 2014). Consistent with a previous report (M�ller and Eichacker 1999), LHCB1 protein, the main subunit of LHCII, was undetectable before illumination in both +DEX and −DEX seedlings (Fig.�5C). At 3 h after illumination, LHCB1 became detectable with both treatments (Fig.�5D), although the protein signals, which were similar between +DEX and −DEX plants, were very faint (Fig.�5C). In −DEX seedlings, LHCB1 level further increased during illumination and showed an intense signal at 24 h after illumination. In contrast, in +DEX seedlings, LHCB1 protein accumulation was strongly impaired at 6 h after illumination and the signal remained minor even after 24 h.

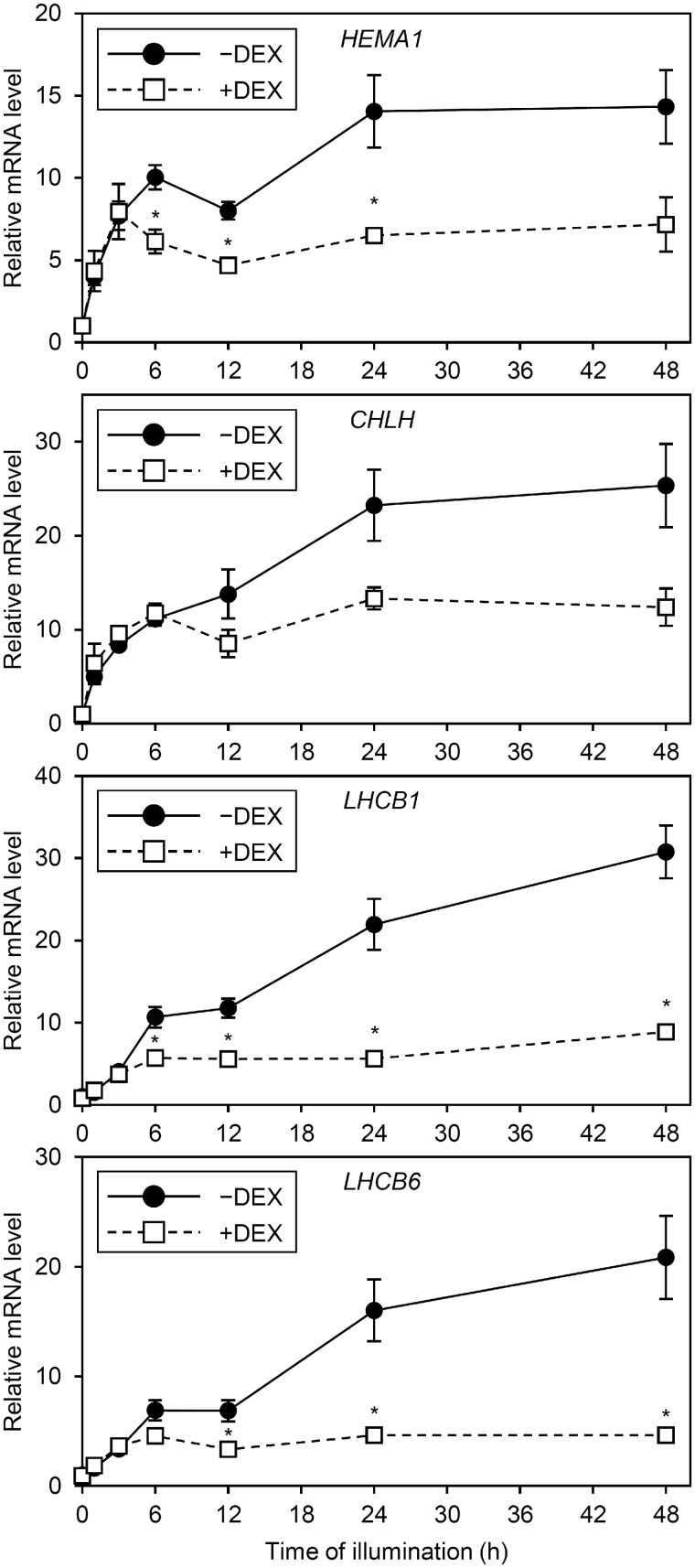

MGD1 suppression does not affect acute induction of genes for Chl biosynthesis and light-harvesting after illumination

To examine whether changes in gene expression are involved in impaired accumulation of Chl and LHCB1 protein in +DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings, we measured mRNA levels of genes for Chl biosynthesis and light-harvesting before and after illumination (Fig.�6). The mRNA levels of HEMA1 encoding glutamyl-tRNA reductase and CHLH encoding the H subunit of Mg-chelatase, key genes for Chl biosynthesis (Tanaka et�al. 2011), were not changed by MGD1 suppression in dark-grown seedlings (Fujii et�al. 2017). In addition, the mRNA levels of LHCB1 for the major LHCII protein and LHCB6 for the minor PSII antenna protein (CP24) were similar between −DEX and +DEX plants in the dark. After illumination, the mRNA levels of all genes examined increased, with no significant differences between −DEX and +DEX plants before and at 3 h. The mRNA levels of these genes further increased in −DEX but not +DEX seedlings with illumination for 6 h or more. As a result, +DEX seedlings showed much lower expression of these genes than the −DEX control after 24 to 48 h of illumination.

Fig. 6.

mRNA levels of photosynthesis-related genes during greening of dark-grown amiR-MGD1 seedlings. Seedlings were illuminated for 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h after 4-d growth in the dark (0 h) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of DEX. Fold difference from the −DEX control at 0 h after normalization to the control gene ACTIN8 is shown for each gene. Data are mean � SE from 10 (0 h) or 3 (1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 h) independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant difference from the −DEX control (P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). Data for HEMA1, CHLH and LHCB6 before illumination (0 h) were shown based on Fujii et al. (2017)www.plantphysiol.org. Copyright American Society of Plant Biologists.

MGD1 expression during dark growth is essential for greening after illumination

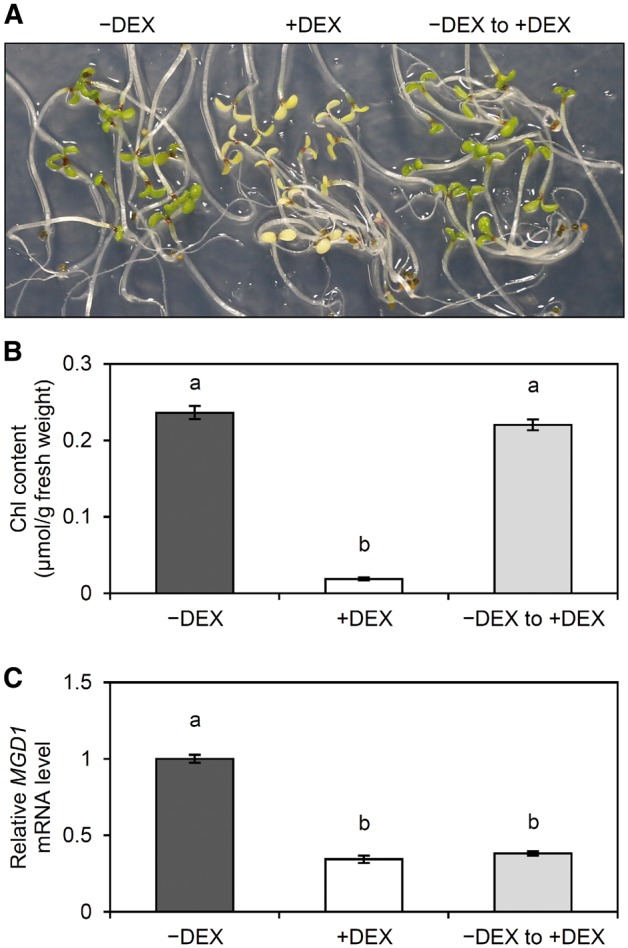

To examine whether the MGD1 expression during etioplast development is important for etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation after illumination, we grew amiR-MGD1 seedlings on DEX-free media in the dark for 3 d, then treated them with DEX for 24 h to fully downregulate the MGD1 expression before illumination. After illumination for 24 h in the presence of DEX, seedling phenotypes were compared with those continuously grown under −DEX or +DEX. Consistent with data in Figs.�1, 5, Chl accumulation was strongly impaired in +DEX seedlings (Fig.�7A, B). Meanwhile, seedlings treated with DEX before illumination showed a phenotype similar to the −DEX control and accumulated Chl to the control level, even though the short DEX treatment suppressed MGD1 mRNA accumulation to the minimal level (Fig.�7C). The data demonstrate that MGD1 expression during etioplast development in the dark is sufficient for chloroplast development after illumination.

Fig. 7.

Greening of dark-grown amiR-MGD1 seedlings treated with DEX after the development in darkness. (A) Phenotype, (B) Chl content and (C) mRNA abundance of MGD1 were analyzed in amiR-MGD1 seedlings illuminated for 24 h after grown in the dark for 4 d. Seedlings indicated as −DEX and +DEX were grown continuously under DEX-free or DEX-fed conditions, respectively, whereas those indicated as ‘−DEX to +DEX’ were treated with DEX 24 h before illumination. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05, Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test).

Loss of DGDG retards conversion of the PLB to the thylakoid membrane during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation

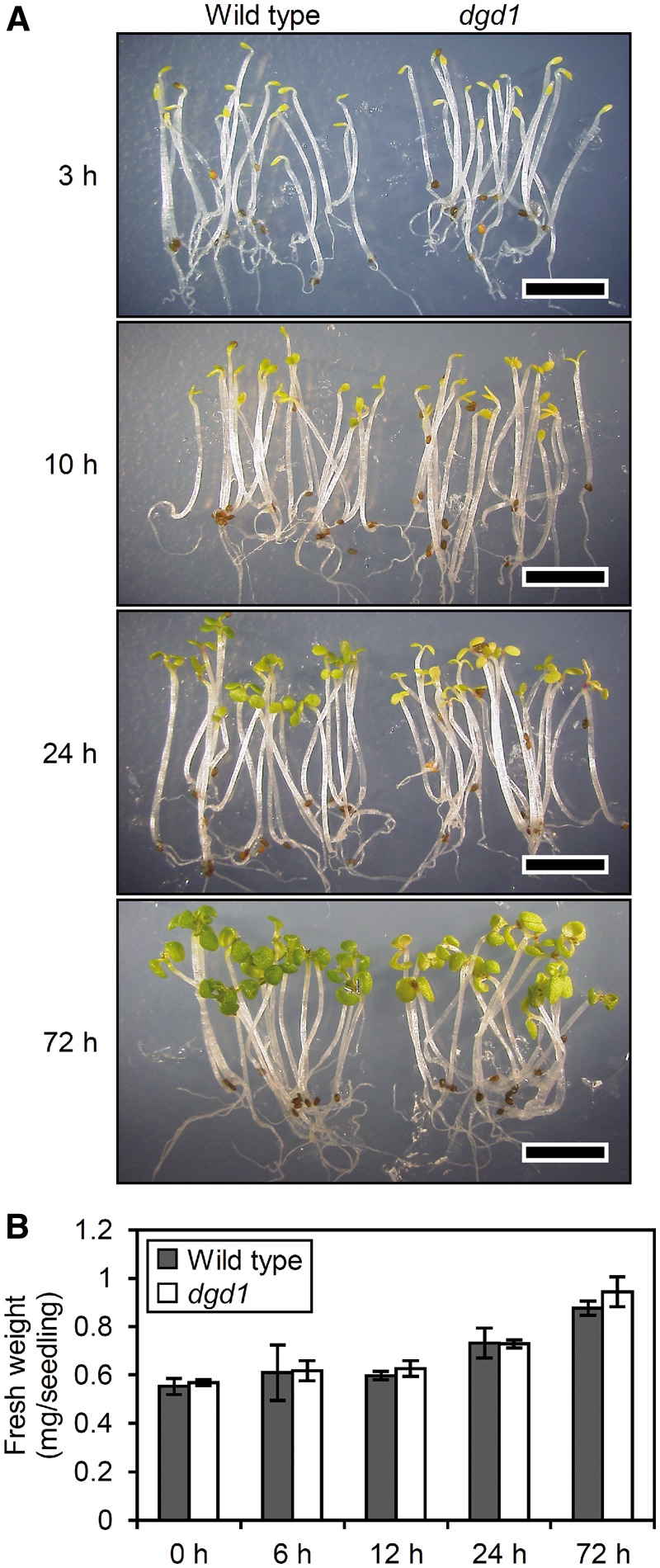

To assess the effect of DGDG deficiency on the etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation after illumination, we analyzed the greening process of dark-grown dgd1 seedlings, in which etioplast development is strongly affected (Fujii et�al. 2018). The cotyledon greening after illumination was delayed in dgd1 as compared with the wild-type Arabidopsis Columbia (Col) plants (Fig.�8A), although fresh weight of the dgd1 seedlings increased similar to the wild type (Fig.�8B). After 72-h illumination, dgd1 recovered from impaired greening to some extent, which was in contrast to the continuous impairment of greening in +DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings (Fig.�1A).

Fig. 8.

(A) Phenotype and (B) fresh weight of dark-grown wild-type and dgd1 seedlings after illumination. Plants were grown for 4 d in the dark and then illuminated for indicated hours. Bars in (A) = 5.0 mm. Data in (B) are mean � SE from three (0 h) or four (6, 12, 24, 72) independent experiments. No significant difference in fresh weight was observed between wild type and dgd1 (P > 0.05, Student’s t-test).

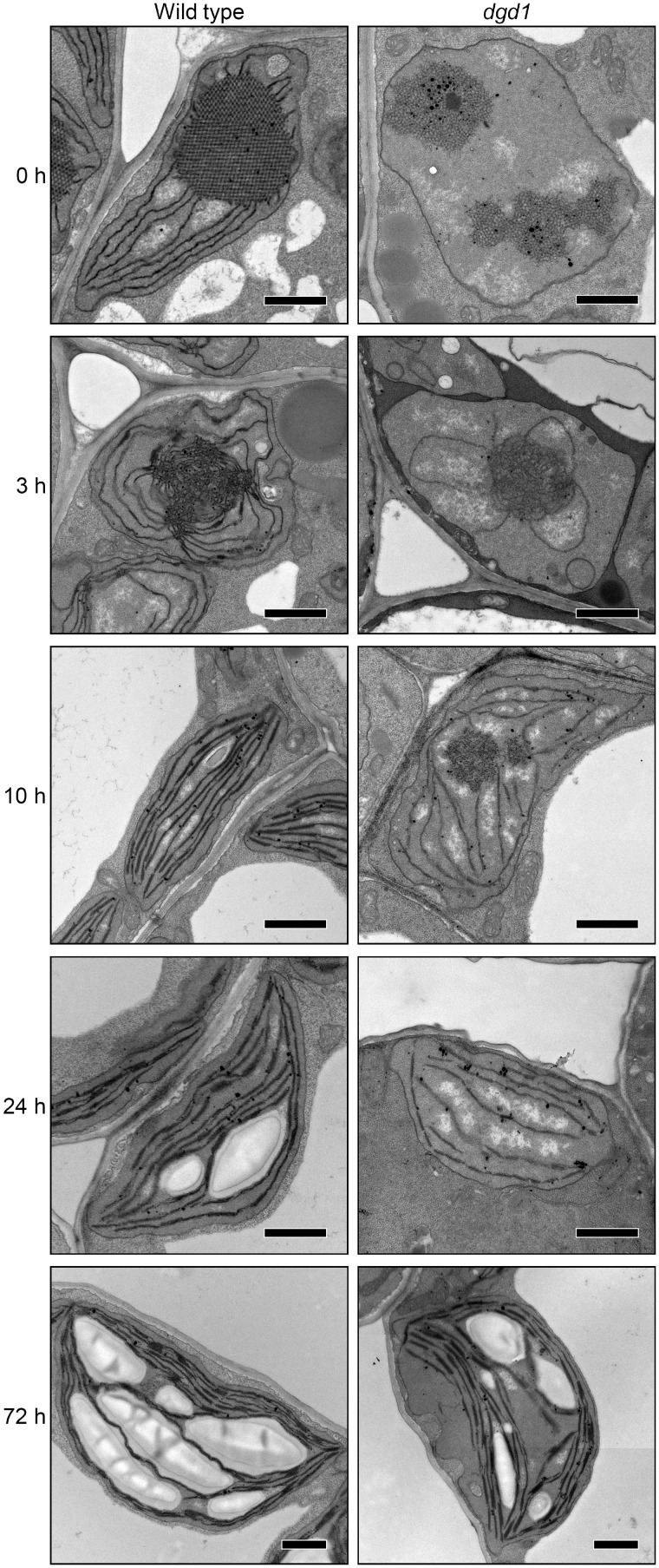

We then investigated plastid ultrastructure in cotyledon cells of dark-grown dgd1 seedlings illuminated for 0, 3, 10, 24 and 72 h with continuous white light (Fig.�9 and Supplementary Fig. S6). As in −DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings, in wild-type Arabidopsis Col plants, the crystalline structure of PLBs observed in etioplasts was disrupted and replaced by irregular membrane aggregates after 3-h illumination. In addition, PTs were further elongated from the PLB remnants, and short stacks of two or three membranes were observed. Most plastids had distorted circular shapes. After 10-h illumination, PLB remnants were no longer detected in all wild-type plastids, and instead, lamellar thylakoid membranes were extensively developed. In addition, long-stacked regions of two or three membranes were frequently observed, occasionally forming thick stacks of four to six membranes. The plastids had elliptical or spindle shapes with thylakoid membranes oriented toward each apex. After 24-h illumination, plastids in wild-type cotyledons contained large starch granules between thylakoid membranes, which were further enlarged after 72 h, and appeared as typical chloroplasts with a lens-like shape.

Fig. 9.

Changes in ultrastructure of cotyledon plastids during greening of dark-grown seedlings of the Arabidopsis Columbia wild type and the dgd1 mutant. Plants were grown for 4 d in the dark and then illuminated for indicated hours. Bars = 1.0 μm.

As we previously reported (Fujii et�al. 2018), in dark-grown dgd1 etioplasts, alignment of PLB lattices was strongly disturbed and the development of PTs was severely impaired. After 3-h illumination, the PLB lattice membranes were converted to aggregates of irregular membrane tubules as in the wild type, but the growth of PTs was still impaired and no stacks of lamellar membranes were observed. After 10-h illumination, large circular aggregates of membrane tubules, which would be remnants of PLBs, were frequently observed in dgd1 plastids. Development of thylakoid membranes was strongly impaired, and stacked membrane regions were rarely observed in the mutant. After 24-h illumination, the thylakoid membrane development was still strongly impaired and no grana stacks were formed. Some plastids still contained circular aggregates of membrane tubules, presumably PLB remnants (see Supplementary Fig. S6A). Of note, high electron-dense particles similar to plastoglobuli were often observed around the tubule aggregates. After 72-h illumination, circular aggregates of membrane tubules were not observed in dgd1 cotyledons. Some mutant plastids developed wild-type-like thylakoid membrane networks and accumulated starch granules, although thylakoid-free areas were often observed, as reported previously (D�rmann et�al. 1995). Plastids with underdeveloped thylakoid membranes were still observed in cotyledon cells of some dgd1 seedlings at 72 h after illumination (see Supplementary Fig. S6B).

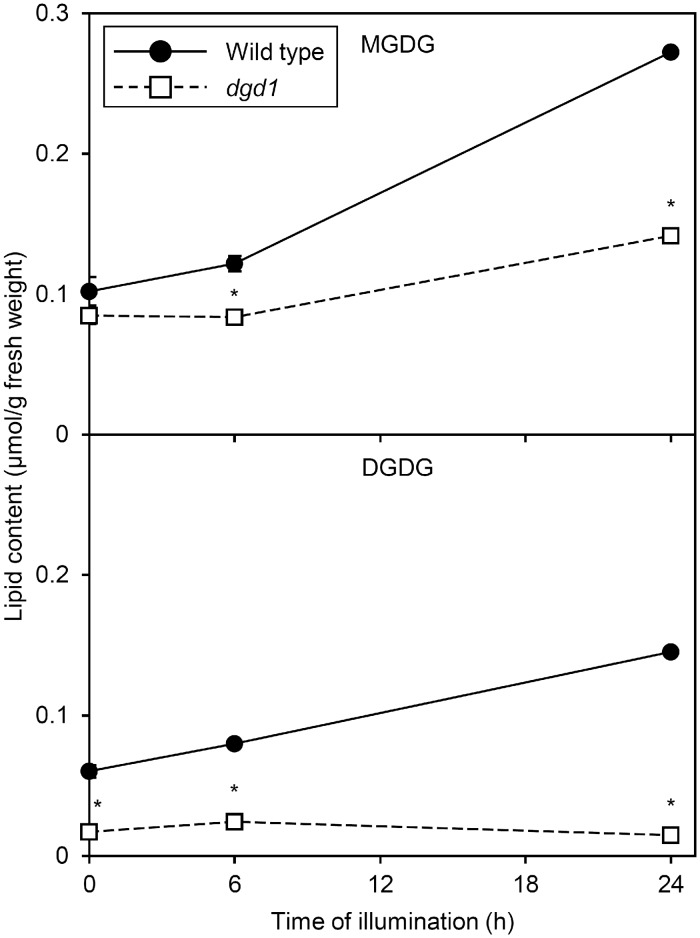

Galactolipid biosynthesis during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation is impaired by disruption of DGD1

In contrast to amiR-MGD1 lines, in dark-grown dgd1 seedlings, DGDG but not MGDG content was remarkably decreased (Fig.�10; Fujii et�al. 2018). In the wild type, but not dgd1, both MGDG and DGDG content slightly increased after 6 h of illumination. After 24-h illumination, MGDG content increased in dgd1 seedlings but to a lesser extent than in the wild type, so MGDG content in dgd1 was about half of the wild-type level. Moreover, unlike in the wild type, in dgd1, DGDG content did not increase in response to illumination. Thus, DGDG content in dgd1 seedlings was only 10% of the wild-type level after 24-h illumination. Similar results were observed in proportion of galactolipids in total membrane lipids (see Supplementary Fig. S7).

Fig. 10.

Galactolipid content during greening of dark-grown seedlings of the Arabidopsis Columbia wild type and the dgd1 mutant. Plants were grown for 4 d in the dark and then illuminated for indicated hours. Data are mean � SE from three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant difference from the wild type (P < 0.05, Student’s t-test).

Disruption of DGD1 changes FA composition of galactolipids during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation

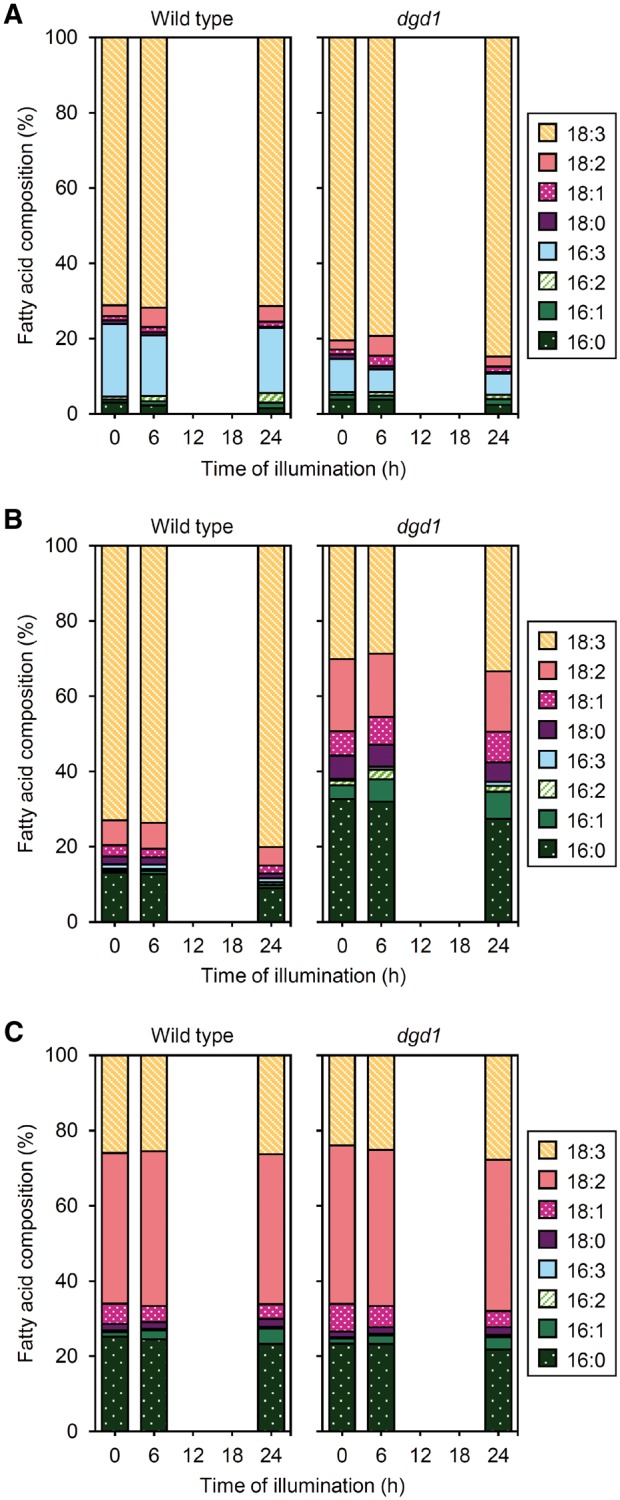

Similar to −DEX amiR-MGD1 plants with a Landsberg erecta background, wild-type Col seedlings showed only slight changes in FA composition of MGDG with illumination (Fig.�11A). In DGDG, the proportion of 18:3 was increased and those of 18:2 and 16:0 were slightly decreased in the illuminated wild type (Fig.�11B). We previously reported that FA composition of MGDG and DGDG in dark-grown dgd1 seedlings greatly differed from that in the wild type (Fujii et�al. 2018). The proportions of 16:3 and 18:3 in MGDG were lower and higher, respectively, in dark-grown dgd1 than the wild type (Fig.�11A). The proportion of 18:3 in DGDG was lower and those of other FAs were higher in the mutant than the wild type (Fig.�11B). Altered FA composition was also observed in dgd1 after illumination. In MGDG of the mutant, the proportions of 16:3 and 18:3 were further decreased and increased, respectively, after 24-h illumination. Moreover, the absolute amount of 18:3 was specifically increased in the mutant MGDG after 24-h illumination (see Supplementary Fig. S8A). In the mutant DGDG, the proportions of 18:3, 18:1 and 16:1 were increased and those of 16:0 and 18:2 were decreased with 24-h illumination (Fig.�11B). However, on a fresh weight basis, the amounts of 18:3, 18:1 and 16:1 in DGDG did not increase during this period (see Supplementary Fig. S8B), which agrees with the decreased total DGDG content after 24-h illumination (Fig.�10). Meanwhile, dgd1 mutation did not affect the composition of total FAs from other membrane lipids before and after illumination (Fig.�11C).

Fig. 11.

Changes in FA composition of galactolipids during greening of dark-grown seedlings of wild type and the dgd1 mutant. FA composition of (A) MGDG, (B) DGDG and (C) other membrane lipids in seedlings illuminated for indicated hours after 4-d growth in the dark. Data are means from three independent experiments.

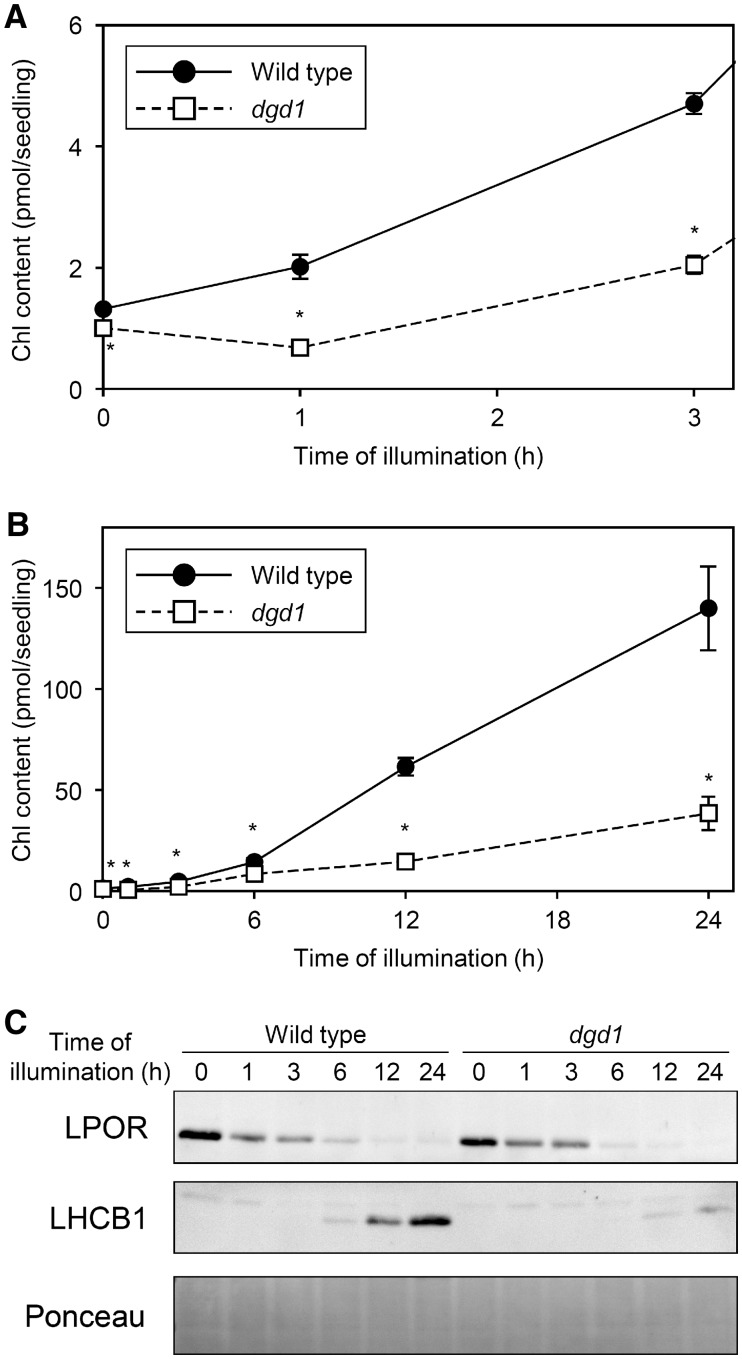

Disruption of DGD1 strongly impairs accumulation of Chl and LHCB1 during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation

Consistent with our previous study showing that dgd1 mutation impaired Pchlide accumulation in dark-grown seedlings (Fujii et�al. 2018), the amount of Chl after 1-h illumination was lower in dgd1 than wild-type seedlings (Fig.�12A). In dgd1, Chl content at 1 h after illumination was 0.68 pmol/seedling, which was lower than Pchlide content before illumination (1.00 pmol/seedling; Fujii et�al. 2018). Although Chl content increased in dgd1 afterward, the accumulation rate was remarkably slower than in wild-type seedlings (Fig.�10B), resulting in the delayed greening of the mutant cotyledons (Fig.�8).

Fig. 12.

Changes in Chl and protein contents during greening of dark-grown seedlings of the Arabidopsis Columbia wild type and dgd1 mutant. Seedlings were illuminated for indicated hours after 4-d growth in the dark. (A, B) Chl content per seedling. Amount of protochlorophyllide (Fujii et al. 2018, www.plantphysiol.org. Copyright American Society of Plant Biologists) is shown for 0 h instead of Chl amount. Data are mean � SE from 18 (0 h) or 3 (1, 3, 6, 12, 24 h) independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant difference from the wild-type control (P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). (A) is an enlarged view of (B) within 3 h of illumination. (C) Immunoblot analysis of LPOR and LHCB1 proteins. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Unspecific bands were constantly observed above the LHCB1 bands. Ponceau-stained proteins are shown as a loading control.

We next examined whether the dgd1 mutation affects protein accumulation during the greening process. LPOR protein level, which was slightly lower in dark-grown dgd1 than wild-type seedlings as observed previously (Fujii et�al. 2018), rapidly decreased both in dgd1 and the wild type with illumination (Fig.�12C). In contrast to LPOR protein level, LHCB1 level increased with illumination in wild-type seedlings. However, in dgd1, the accumulation of LHCB1 was very slow and the signals were faint even after 24-h illumination.

Discussion

Galactolipids deficiency impairs accumulation of Chl and Chl-binding proteins during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation

We previously reported that MGDG deficiency in amiR-MGD1 etioplasts impaired membrane-associated processes of the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway and thus decreased Pchlide accumulation in the dark (Fujii et�al. 2017). In +DEX seedlings, Chl content after 1-h illumination was comparable to the Pchlide level before illumination, which indicates strong inhibition of de novo Chl biosynthesis by MGD1 suppression (Fig.�5A). In contrast, the mRNA levels of HEMA1 and CHLH, which show strong coexpression with other Chl biosynthesis genes (Kobayashi and Masuda 2016), rapidly increased in +DEX seedlings as in the −DEX control until 3 or 6 h of illumination (Fig.�6). The data suggest that in +DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings, inhibited accumulation of Chl within the first several hours after illumination is not caused by transcriptional downregulation. As observed in dark-grown seedlings, MGDG deficiency likely impairs the membrane processes of the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway after illumination. Because dgd1 mutation also impaired membrane processes of the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in etioplasts (Fujii et�al. 2018), the inhibited Chl accumulation in dgd1 seedlings shortly after illumination may be explained by the same mechanism. Of note, in dgd1, Chl content at 1 h after illumination was even lower than Pchlide content before illumination (Fig.�12A;Fujii et�al. 2018). We previously reported that dgd1 mutation retarded the regeneration of photoactive Pchlide–LPOR complexes from nonphotoactive forms, which is required for subsequent steps of Chl biosynthesis (Fujii et�al. 2018). In the mutant, the decreased Chl formation at the beginning of greening may be explained in part by the retarded regeneration of photoactive Pchlide-LPOR complexes.

Accumulation of the LHCB1 protein was also impaired in +DEX amiR-MGD1 (Fig.�5C) and dgd1 seedlings (Fig.�12C). Because Chl is important for the accumulation of LHCPs in membranes, impaired Chl accumulation might result in decreased LHCB1 levels in these plants. However, we found no noticeable differences in LHCB1 levels between +DEX and −DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings at 3 h after illumination (Fig.�5D), although the Chl content was remarkably lower in +DEX than −DEX control seedlings (Fig.�5A). Because LHCB1 level was very low at this period, reduced Chl level in +DEX seedlings may be sufficient for the initial LHCB1 accumulation.

Although +DEX seedlings showed an acute induction of LHCB1 gene expression similar to the −DEX control during 3-h illumination, unlike the −DEX control, +DEX seedlings showed no enhancement of LHCB1 expression thereafter (Fig.�6). In addition to the impaired Chl biosynthesis, inhibited induction of the LHCB1 gene expression might decrease the accumulation of LHCB1 protein at later greening stages in +DEX seedlings. Similar transcriptional trends were observed in HEMA1, CHLH and LHCB6 genes, which is consistent with our previous report that decreased MGDG biosynthesis downregulated the expression of photosynthesis-associated genes in light-grown seedlings (Kobayashi et�al. 2013, Fujii et�al. 2014). In +DEX seedlings, some impairments in the process of chloroplast development, caused by MGD1 dysfunction within 6 h after illumination, might activate a regulatory system to suppress the expression of photosynthesis-associated genes. In addition, we do not exclude that galactolipid deficiency directly destabilizes LHCII proteins and impairs their accumulation in membranes. In fact, single-molecule force spectroscopy analysis of LHCII embedded in lipid bilayers revealed that MGDG with a conical shape increased the mechanical stability of LHCII (Seiwert et�al. 2017), which suggests a requirement of MGDG for stable accumulation of LHCII in the thylakoid membrane.

Mechanism of impaired PLB-to-thylakoid transformation by galactolipid deficiency during illumination

In −DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings, PLB remnants observed at 3 h after illumination were mostly transformed into thylakoid membranes after 6 h (Fig.�2). Previous studies showed that the lipid composition of PLBs is similar to that of the thylakoid membrane (Selstam and Sandelius 1984, Dorne et�al. 1990). Moreover, both MGDG and DGDG content did not largely increase during the early greening stages (Figs.�3, 10), which agrees with no increase in galactolipid content in dark-grown barley seedlings with illumination for several hours (Selld�n and Selstam 1976). These data suggest that most galactolipids in PLBs are used for constructing the thylakoid membrane. This assumption is consistent with the observation that tubular structures of PLBs are directly transformed into flat slats of the thylakoid membrane during the etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation (Kowalewska et�al. 2016). In addition, we observed that MGD1 suppression from 24 h before illumination did not inhibit greening of seedlings after illumination (Fig.�7). Thus, although MGD1 is light-inducible, the MGD1 protein or galactolipids already synthesized during the dark growth may be sufficient for the initial processes of the etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation. DGD1 is also weakly light-inducible (Kobayashi et�al. 2014). The light-induced expression of these genes may contribute to increased galactolipid content at the later stages of chloroplast development. In fact, +DEX seedlings of a weak amiR-MGD1 line (L4g) showed decreased Chl levels only after 24-h illumination (see Supplementary Fig. S5), which suggests that full expression of MGD1 is required for chloroplast development at the later greening stage when galactolipid content increases.

As in the −DEX control, in +DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings, PLB remnants were mostly disassembled after 6-h illumination (Fig.�2). However, in these seedlings, many plastids failed to develop stacked thylakoid membrane networks. Seiwert et�al. (2018) proposed that nonbilayer-forming MGDG promotes membrane stacking by easing the membrane curvature stress in the margin domains, which suggests a structural importance of MGDG for thylakoid membrane development. In addition to a direct effect of MGDG deficiency on membrane biogenesis, in +DEX seedlings, lack of LHCII and possibly other LHCPs may negatively affect thylakoid membrane formation after disassembly of PLBs. This assumption is consistent with the observation that grana stacking, with LHCII playing a crucial role (Pribil et�al. 2014), was severely underdeveloped in +DEX chloroplasts. Although some plastids in +DEX seedlings could form a thylakoid membrane at 6 h after illumination, all plastids observed after 20-h illumination showed poorly developed internal membrane networks. This observation is consistent with the decreased content of both galactolipids from 6- to 24-h illumination in +DEX seedlings (Fig.�3), which would further impair thylakoid biogenesis in chloroplasts. In +DEX seedlings, downregulation of photosynthesis-associated genes in response to decreased MGDG biosynthesis may secondarily suppress chloroplast biogenesis and result in stronger impairment of the thylakoid membrane development at later stages of greening.

In contrast to +DEX amiR-MGD1, the dgd1 mutant showed PLB remnants in plastids at 10 h after illumination and even after 24-h illumination in some cases (Fig.�9 and Supplementary Fig. S6). Because LPORs, which determine the size of PLBs as essential constituents (Sperling et�al. 1998, Franck et�al. 2000, Masuda et�al. 2003), were rapidly degraded in dgd1 as in the wild-type control (Fig.�12C), LPOR protein may not be involved in the retarded disassembly of PLBs in illuminated dgd1 seedlings. Moreover, inhibited accumulation of Chl and LHCB1 would not be a cause of retarded PLB disassembly in dgd1 because amiR-MGD1 having similar inhibition in these processes showed rapid PLB disassembly. Considering that the dgd1 mutant had a remarkably high MGDG-to-DGDG ratio (Fig.�10) and MGDG cannot form bilayer membranes by itself in vitro (Shipley et�al. 1973), the high proportion of MGDG in PLBs may inhibit disassembly of PLBs and subsequent formation of lamellar lipid bilayer membranes even after degradation of LPORs. After 24-illumination, development of the thylakoid membrane with grana stacks was still strongly arrested in dgd1 chloroplasts (Fig.�9). Because LHCII is required for thylakoid membrane stacking, lack of LHCII protein may perturb the development of multilamellar thylakoid membrane networks in this mutant. In addition to LHCII and MGDG, DGDG may be involved in stacking the thylakoid membranes, as Kanduč et�al. (2017) suggested with molecular dynamics simulations showing that saccharide headgroups of DGDG play an important role in tight cohesion of photosynthetic membranes with stable multilamellar structures. Of note, the dgd1 mutant showed cotyledon greening (Fig.�8A) and could form a thylakoid membrane (Fig.�9) after longer exposure to light. Because MGDG can form lamellar membranes with LHCII in vitro (Simidjiev et�al. 2000), the gradual increase in LHCII content in dgd1 during illumination may induce thylakoid membrane formation with a lipid pool rich in MGDG. This assumption is supported by the dgd1 mutant grown under light from the beginning of germination showing accumulated LHCII protein to the wild-type level and forming the highly developed thylakoid membrane as did wild-type chloroplasts (D�rmann et�al. 1995, H�rtel et�al. 1997).

In both +DEX amiR-MGD1 and dgd1 seedlings, clusters of high electron-dense particles similar to plastoglobuli were frequently observed along with underdeveloped thylakoid membranes in immature chloroplasts. Etioplasts contain a number of plastoglobuli in PLBs. However, during the etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation, the abundance of plastoglobuli decreases concomitant with the transformation of PLBs to the thylakoid membrane (Rottet et�al. 2015). This observation suggests that plastoglobuli, which include neutral lipids such as prenylquinones, carotenoids, phytylesters and triacylglycerols, contribute to thylakoid development presumably by supplying these hydrophobic compounds. However, in +DEX amiR-MGD1 and dgd1 seedlings, the thylakoid development was strongly impaired, so neutral lipids that cannot be distributed to the thylakoid membrane might accumulate in plastoglobule-like lipid droplets.

Galactolipid metabolism during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation

In addition to impaired MGDG accumulation, the light-induced increase in DGDG content was impaired in +DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings. Because DGDG is synthesized from MGDG, the impaired DGDG accumulation in +DEX seedlings can be explained by decreased MGDG biosynthesis. After illumination, MGDG content as well as DGDG content was lower in the dgd1 mutant than the wild type, although MGDG is the substrate for DGDG biosynthesis. Because the expression of both MGD1 and DGD1 is downregulated in response to chloroplast dysfunction (Kobayashi et�al. 2014), the decrease in one of the galactolipids and consequent impaired chloroplast development may downregulate the expression of galactolipid biosynthesis genes and decrease the biosynthesis of the other galactolipid. Moreover, MGD1 needs to be reduced by thioredoxin for activation (Yamaryo et�al. 2006), so photosynthetic perturbation may also decrease MGDG biosynthesis activity in these plants.

In −DEX amiR-MGD1 and wild-type Col seedlings, FA composition in galactolipids did not largely change before and after illumination (Figs.�4, 11). The data suggest that the galactolipid metabolic pathway is not largely altered during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation. In contrast to the −DEX control, +DEX amiR-MGD1 seedlings showed remarkable changes in FA composition of MGDG with illumination, particularly during 6 to 12 h (Fig.�4A). Because galactolipid content did not largely change during this period (Fig.�3), MGDG may be subject to active turnover. Considering that the 16:3-containing MGDG, which is exclusively produced via the plastid pathway, is scarcely used for DGDG biosynthesis as a substrate (Browse and Somerville 1991, Ohlrogge and Browse 1995), the decrease in 16:3 and 18:3 proportions in MGDG of +DEX seedlings implies active degradation of 18:3/16:3-MGDG molecular species. In contrast, the proportions of 16:1 and 18:0 were increased in +DEX seedlings. In Arabidopsis, 16:1 does not originate from the ER pathway because of lack of particular desaturases (Li-Beisson et�al. 2013), so the increase in 16:1 proportion in MGDG may reflect decreased activity of FA desaturase (FAD) 6, which desaturates 16:1 and 18:1 to 16:2 and 18:2 in plastids. This suggestion also implies that FAD5, which specifically desaturates 16:0 at the sn-2 of MGDG to 16:1 in plastids (Heilmann et�al. 2004), is functional in +DEX seedlings. In addition, the accumulation of 18:0 in MGDG under the +DEX condition may reflect decreased desaturation of 18:0-ACP to 18:1-ACP by SAD. Because the major function of MGD2 and MGD3 is to supply MGDG to DGDG biosynthesis at the outer envelope (Kobayashi et�al. 2009a), presumably via the ER pathway, most of the MGDG in +DEX seedlings may be derived from MGD1 activity leaked from the amiR-MGD1 suppression.

In +DEX seedlings, the FA composition of DGDG changed after illumination, with 16:0 and 18:3 proportions showing an increase and decrease, respectively (Fig.�4B). Considering that the alternative pathway by MGD2, MGD3 and DGD2 preferentially synthesizes 16:0-containing DGDG species (Kelly et�al. 2003, Kobayashi et�al. 2009a), the contribution of this pathway may be enhanced in +DEX seedlings vs. the −DEX control. In this context, the gradual increase in 16:0 proportion in MGDG of +DEX seedlings may also reflect increased contribution of MGD2 and MGD3 to MGDG biosynthesis. However, no compensatory increases in the mRNA levels of MGD2, MGD3, DGD1 and DGD2 in response to MGD1 suppression were observed in +DEX seedlings (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Thus, the increased contribution of the alternative pathway in +DEX seedlings may simply result from altered metabolic flow from the main MGD1 pathway to the MGD2-MGD3 pathway due to the MGD1 deficiency. Of note, unlike in MGDG, in DGDG of +DEX seedlings, the 18:0 proportion did not strongly increase after illumination. As discussed earlier, in +DEX seedlings, 18:0-ACP may be accumulated in addition to 18:1-ACP because of decreased SAD activity. One possibility is that 18:1-ACP is immediately hydrolyzed to free FAs after desaturation by SAD and used for the ER pathway, whereas 18:0-ACP, which is not a good substrate for plastid thioesterases (Ohlrogge and Browse 1995, Li-Beisson et�al. 2013), is retained within plastids and used for the plastid pathway. Therefore, in +DEX seedlings, MGDG produced via the plastid pathway may contain high levels of 18:0, whereas DGDG produced via the ER pathway may be devoid of 18:0. The reason why some desaturase activities appear to be specifically downregulated in +DEX seedlings after illumination remains elusive.

FA compositions of MGDG and DGDG greatly differed in the dark-grown dgd1 mutant from those in the wild type, and the difference continued even after 24 h of illumination (Fig.�11). In the Arabidopsis wild type, MGD1 synthesizes C18/C16-MGDG via the plastid pathway and C18/C18-MGDG via the ER pathway (Browse and Somerville 1991, Ohlrogge and Browse 1995). Among these MGDG species, DGD1 mainly consumes the C18/C18-MGDG to form 18:3/18:3-DGDG, and therefore, 18:3/16:3-MGDG remains at a high proportion. In the dgd1 mutant, many C18/C18-MGDG molecules remain unconverted to DGDG because of lack of DGD1, leading to an accumulation of 18:3/18:3-MGDG, so the proportion of 18:3 in MGDG might increase and that of 16:3 relatively decrease. In the mutant DGDG, the proportion of 18:3 substantially decreased and those of other FAs, particularly 16:0, increased. These changes would be due to the enzymatic property of DGD2 as reported previously (Kelly et�al. 2003).

Requirements of galactolipids for internal membrane transformation during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation

In summary, our data show that MGDG deficiency by MGD1 suppression during the etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation did not perturb degradation of LPORs and disassembly of PLBs but inhibited the development of thylakoid membrane networks after PLB disassembly. Chl accumulation shortly after illumination was impaired by the MGDG deficiency, presumably because of inhibited membrane-associated processes of the Chl biosynthesis pathway. The MGD1 suppression did not impair an initial increase in mRNA and protein levels of LHCB1 at the beginning of greening but abolished their accumulation as well as the light-induced increase in DGDG content at later stages. Downregulation of LHCB gene expression and destabilization of LHCII by Chl deficiency both decrease LHCII levels, which, in addition to the direct effect of galactolipid deficiency on membrane formation, may inhibit thylakoid membrane biogenesis after PLB disassembly.

DGDG deficiency by loss of DGD1 also impaired the accumulation of Chl and LHCB1 protein after illumination. Unlike MGDG deficiency, DGDG deficiency retarded disassembly of PLB remnants after illumination despite rapid degradation of LPORs. Because loss of DGD1 results in a high ratio of nonbilayer-forming MGDG to bilayer-forming DGDG, the high proportion of MGDG may impair transformation from PLB remnants to lamellar membranes. However, after long exposure to light, dgd1 seedlings developed thylakoid membrane networks with grana stacks, presumably with gradually accumulating LHCII, which can induce MGDG to form bilayer membranes.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The amiR-MGD1 transgenic lines (Fujii et�al. 2014, Fujii et�al. 2017) and dgd1 mutant (D�rmann et�al. 1995) were Landsberg erecta and Col ecotypes, respectively, of A. thaliana. Surface-sterilized seeds were incubated at 4�C for 3 or 4 d in the dark. Seeds were sown on 0.8% (w/v) agar-solidified Murashige and Skoog medium containing 1% (w/v) sucrose and illuminated for 3 h under room lights to synchronize germination. Then seeds were incubated at 23�C for 4 d in complete darkness. Etiolated seedlings were illuminated with continuous white light (50 μmol photons m−2 s−1) at 23�C. For DEX treatment, DEX (Wako) was added to a final concentration of 10 μM in the medium from a 50 mM stock in dimethyl sulfoxide.

Fresh weight measurement

Twenty dark-grown seedlings were collected from agar-solidified media before or after illumination and weighed immediately after quick removal of water attached to the sample surface.

Transmission electron microscopy

Ultrathin sections of fixed cotyledon samples were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed by transmission electron microscope as described (Fujii et�al. 2017).

Lipid analysis

Total lipids were extracted from seedlings and separated by thin-layer chromatography as described (Kobayashi et�al. 2006, Fujii et�al. 2017). The content of MGDG, DGDG and a mixture of other glycerolipids was quantified by gas chromatography (GC-17A; Shimadzu) as described (Fujii et�al. 2017).

Determination of Chl content

To extract Chl, intact seedlings were incubated in 80% (v/v) acetone at 4�C in darkness for 2 or 3 d. Chl content in extracts was determined by measuring the absorbance at 663 and 645 nm with a V-370 BIO (JASCO) spectrophotometer as described (Melis et�al. 1987) or measuring fluorescence emission at 666 nm under 440-nm excitation with a RT-5300PC spectrofluorometer (Shimadzu) by using the Chl standard sample of known concentration as described previously (Fujii et�al. 2014).

Immunoblot analysis

For the data in Figs.�5C, 12C, 10 μg total protein extracted from seedlings was separated by SDS-PAGE as described (Fujii et�al. 2017). For Fig.�5D, 50 μg total protein was used to detect faint LHCB1 signals from 3-h illuminated samples. Polyclonal antibodies that react with total LPOR protein (Masuda et�al. 2003) and LHCB1 (AgriSera) were used as primary antibodies to detect total LPOR (PORA, PORB and PORC) and LHCB1 protein, respectively. Protein signals were measured as described (Fujii et�al. 2017). Ponceau-stained proteins between 35 and 50 kDa blotted on nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Protran Premium 0.2 NC; GE Healthcare) were loading controls.

qRT-PCR analysis

Transcript abundance was quantified as described (Fujii et�al. 2017). Gene-specific primers shown in Supplementary Table S1 were used to amplify cDNA. To quantify LHCB1 mRNA levels, primers were designed to amplify LHCB1.2 (At1g29910), but might also amplify LHCB1.1 (At1g29920) and LHCB1.3 (At1g29930) with the nucleotide length (381 bp) being the same as that from LHCB1.2, because the forward primer perfectly binds to the LHCB1.1 and LHCB1.3 sequences and the reverse primer has only a single mismatch to the binding sites of LHCB1.1 and LHCB1.3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter D�rmann (Department of Molecular Biotechnology, Institute of Molecular Physiology and Biotechnology of Plants, University of Bonn) for supplying the dgd1 mutant and Megumi Kobayashi (Department of Chemical and Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Japan Women’s University) for technical assistance with transmission electron microscopy.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [KAKENHI No. 16J10176 to S.F., No. 26711016 to K.K. and No. 26440170 to N.N.].

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Apitz J., Schmied J., Lehmann M.J., Hedtke B., Grimm B. (2014) GluTR2 complements a hema1 mutant lacking glutamyl-tRNA reductase 1, but is differently regulated at the post-translational level. Plant Cell Physiol. 55: 645–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang W.Y., Jeong I.S., Kim D.W., Im C.H., Ji C., Hwang S.M., et al. (2008) Role of Arabidopsis CHL27 protein for photosynthesis, chloroplast development and gene expression profiling. Plant Cell Physiol. 49: 1350–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning C., Ohta H. (2005) Three enzyme systems for galactoglycerolipid biosynthesis are coordinately regulated in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 2397–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist L.A., Ryberg M., Sundqvist C. (2008) Proteomic analysis of highly purified prolamellar bodies reveals their significance in chloroplast development. Photosynth. Res. 96: 37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browse J., Somerville C. (1991) Glycerolipid synthesis: biochemistry and regulation. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 42: 467–506. [Google Scholar]

- Dem� B., Cataye C., Block M.A., Mar�chal E., Jouhet J. (2014) Contribution of galactoglycerolipids to the 3-dimensional architecture of thylakoids. FASEB J. 28: 3373–3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D�rmann P., Hoffmann-Benning S., Balbo I., Benning C. (1995) Isolation and characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant deficient in the thylakoid lipid digalactosyl diacylglycerol. Plant Cell 7: 1801–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorne A., Joyard J., Douce R. (1990) Do thylakoids really contain phosphatidylcholine? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87: 71–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck F., Sperling U., Frick G., Pochert B., van Cleve B., Apel K., et al. (2000) Regulation of etioplast pigment-protein complexes, inner membrane architecture, and protochlorophyllide a chemical heterogeneity by light-dependent NADPH: protochlorophyllide oxidoreductases A and B. Plant Physiol. 124: 1678–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick G., Su Q., Apel K., Armstrong G.A. (2003) An Arabidopsis porB porC double mutant lacking light-dependent NADPH: protochlorophyllide oxidoreductases B and C is highly chlorophyll-deficient and developmentally arrested. Plant J. 35: 141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii S., Kobayashi K., Nagata N., Masuda T., Wada H. (2017) Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol facilitates synthesis of photoactive protochlorophyllide in etioplasts. Plant Physiol. 174: 2183–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii S., Kobayashi K., Nagata N., Masuda T., Wada H. (2018) Digalactosyldiacylglycerol is essential for organization of the membrane structure in etioplasts. Plant Physiol. 177: 1487–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii S., Kobayashi K., Nakamura Y., Wada H. (2014) Inducible knockdown of MONOGALACTOSYLDIACYLGLYCEROL SYNTHASE1 reveals roles of galactolipids in organelle differentiation in Arabidopsis cotyledons. Plant Physiol. 166: 1436–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- H�rtel H., Lokstein H., D�rmann P., Grimm B., Benning C. (1997) Changes in the composition of the photosynthetic apparatus in the galactolipid-deficient dgd1 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 115: 1175–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann I., Mekhedov S., King B., Browse J., Shanklin J. (2004) Identification of the Arabidopsis palmitoyl-monogalactosyldiacylglycerol Δ7-desaturase gene FAD5, and effects of plastidial retargeting of Arabidopsis desaturases on the fad5 mutant phenotype. Plant Physiol. 136: 4237–4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanduč M., Schlaich A., De Vries A.H., Jouhet J., Mar�chal E., Dem� B., et al. (2017) Tight cohesion between glycolipid membranes results from balanced water-headgroup interactions. Nat. Commun. 8: 14899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A.A., Froehlich J.E., D�rmann P. (2003) Disruption of the two digalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase genes DGD1 and DGD2 in Arabidopsis reveals the existence of an additional enzyme of galactolipid synthesis. Plant Cell 15: 2694–2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.H., Li X.P., Razeghifard R., Anderson J.M., Niyogi K.K., Pogson B.J., et al. (2009) The multiple roles of light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-protein complexes define structure and optimize function of Arabidopsis chloroplasts: a study using two chlorophyll b-less mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787: 973–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff H., Mukherjee U., Galla H.J. (2002) Molecular architecture of the thylakoid membrane: lipid diffusion space for plastoquinone. Biochemistry 41: 4872–4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Awai K., Nakamura M., Nagatani A., Masuda T., Ohta H. (2009a) Type-B monogalactosyldiacylglycerol synthases are involved in phosphate starvation-induced lipid remodeling, and are crucial for low-phosphate adaptation. Plant J. 57: 322–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Fujii S., Sasaki D., Baba S., Ohta H., Masuda T., et al. (2014) Transcriptional regulation of thylakoid galactolipid biosynthesis coordinated with chlorophyll biosynthesis during the development of chloroplasts in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 5: 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Kondo M., Fukuda H., Nishimura M., Ohta H. (2007) Galactolipid synthesis in chloroplast inner envelope is essential for proper thylakoid biogenesis, photosynthesis, and embryogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 17216–17221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Masuda T. (2016) Transcriptional regulation of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 7: 1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Masuda T., Takamiya K., Ohta H. (2006) Membrane lipid alteration during phosphate starvation is regulated by phosphate signaling and auxin/cytokinin cross-talk. Plant J. 47: 238–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Nakamura Y., Ohta H. (2009b) Type A and type B monogalactosyldiacylglycerol synthases are spatially and functionally separated in the plastids of higher plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 47: 518–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Narise T., Sonoike K., Hashimoto H., Sato N., Kondo M., et al. (2013) Role of galactolipid biosynthesis in coordinated development of photosynthetic complexes and thylakoid membranes during chloroplast biogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 73: 250–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewska Ł.M., Mazur R., Suski S., Garstka M., Mostowska A. (2016) Three-dimensional visualization of the internal plastid membrane network during runner bean chloroplast biogenesis. Plant Cell 28: 875–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuttkat A., Edhofer I., Eichacker L.A., Paulsen H. (1997) Light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein stably inserts into etioplast membranes supplemented with Zn-pheophytin a/b. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 20451–20455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Beisson Y., Shorrosh B., Beisson F., Andersson M.X., Arondel V., Bates P.D., et al. (2013) Acyl-lipid metabolism. Arabidopsis Book 11: e0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T., Fusada N., Oosawa N., Takamatsu K., Yamamoto Y.Y., Ohto M., et al. (2003) Functional analysis of isoforms of NADPH: protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (POR), PORB and PORC, in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 44: 963–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis A., Spangfort M., Andersson B. (1987) Light-absorption and electron transport balance between photosystem II and photosystem I in spinach chloroplasts. Photochem. Photobiol. 45: 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Moellering E.R., Muthan B., Benning C. (2010) Freezing tolerance in plants requires lipid remodeling at the outer chloroplast membrane. Science 330: 226–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- M�ller B., Eichacker L.A. (1999) Assembly of the D1 precursor in monomeric photosystem II reaction center precomplexes precedes chlorophyll a—triggered accumulation of reaction center II in barley etioplasts. Plant Cell 11: 2365–2377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlrogge J., Browse J. (1995) Lipid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 7: 957–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontier D., Albrieux C., Joyard J., Lagrange T., Block M.A. (2007) Knock-out of the magnesium protoporphyrin IX methyltransferase gene in Arabidopsis. Effects on chloroplast development and on chloroplast-to-nucleus signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 2297–2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribil M., Labs M., Leister D. (2014) Structure and dynamics of thylakoids in land plants. J. Exp. Bot. 65: 1955–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottet S., Besagni C., Kessler F. (2015) The role of plastoglobules in thylakoid lipid remodeling during plant development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1847: 889–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoefs B. (2001) The protochlorophyllide-chlorophyllide cycle. Photosynth. Res. 70: 257–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoefs B., Bertrand M. (2000) The formation of chlorophyll from chlorophyllide in leaves containing proplastids is a four-step process. FEBS Lett. 486: 243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwert D., Witt H., Janshoff A., Paulsen H. (2017) The non-bilayer lipid MGDG stabilizes the major light-harvesting complex (LHCII) against unfolding. Sci. Rep. 7: 5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwert D., Witt H., Ritz S., Janshoff A., Paulsen H. (2018) The nonbilayer lipid MGDG and the major light-harvesting complex (LHCII) promote membrane stacking in supported lipid bilayers. Biochemistry 57: 2278–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selld�n G., Selstam E. (1976) Changes in chloroplast lipids during the development of photosynthetic activity in barley etio‐chloroplasts. Physiol. Plant. 37: 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Selstam E., Sandelius A.S. (1984) A comparison between prolamellar bodies and prothylakoid membranes of etioplasts of dark-grown wheat concerning lipid and polypeptide composition. Plant Physiol. 76: 1036–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley G.G., Green J.P., Nichols B.W. (1973) The phase behavior of monogalactosyl, digalactosyl, and sulphoquinovosyl diglycerides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 311: 531–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simidjiev I., Stoylova S., Amenitsch H., Javorfi T., Mustardy L., Laggner P., et al. (2000) Self-assembly of large, ordered lamellae from non-bilayer lipids and integral membrane proteins in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 1473–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solymosi K., Schoefs B. (2010) Etioplast and etio-chloroplast formation under natural conditions: The dark side of chlorophyll biosynthesis in angiosperms. Photosynth. Res. 105: 143–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling U., Franck F., van Cleve B., Frick G., Apel K., Armstrong G.A. (1998) Etioplast differentiation in arabidopsis: both PORA and PORB restore the prolamellar body and photoactive protochlorophyllide-F655 to the cop1 photomorphogenic mutant. Plant Cell 10: 283–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg E., Slagter J.G., Fridborg I., Cleary S.P., Robinson C., Coupland G. (1997) ALBINO3, an Arabidopsis nuclear gene essential for chloroplast differentiation, encodes a chloroplast protein that shows homology to proteins present in bacterial membranes and yeast mitochondria. Plant Cell 9: 717–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka R., Kobayashi K., Masuda T. (2011) Tetrapyrrole metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Arabidopsis Book 9: e0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaryo Y., Motohashi K., Takamiya K., Hisabori T., Ohta H. (2006) In vitro reconstitution of monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) synthase regulation by thioredoxin. FEBS Lett. 580: 4086–4090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.