Prognosis for many patients with cancer is improving as a result of advances in precision, molecularly targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, but the cost of these treatments continues to rise. One by-product of expensive therapy has been an increase in cost-sharing such that even patients with insurance face a rising and potentially devastating out-of-pocket financial burden.1 For example, a patient with metastatic renal cell cancer might consider treatment with nivolumab, a novel immunotherapy drug that improves median survival by almost 6 months; however, if the patient has Medicare without supplemental insurance or private insurance with 20% coinsurance, he or she could face up to $13,000 in direct costs for this therapy.2 Similarly, Medicare beneficiaries who are diagnosed with cancer have average out-of-pocket expenses that approximate 25% of household income.3 High drug costs threaten not only the sustainability of our health care system, but, more immediately, our patients’ access to care, financial well-being, quality of life, and disease outcomes.4-7

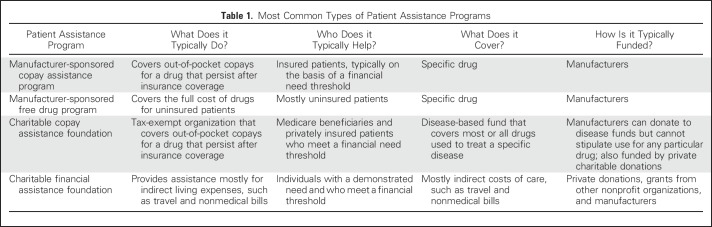

One potential solution to ease the financial burden of a cancer diagnosis is to reduce or eliminate a portion of patient bills through financial assistance programs. The term, patient assistance program, refers to a diverse collection of programs that vary in what they do, who they help, and how they obtain funding (Table 1). We will focus on copay assistance programs, which are sponsored by pharmaceutical manufacturers or charitable foundations to assist insured patients who face high out-of-pocket costs from copayments, coinsurance, or deductibles.

Table 1.

Most Common Types of Patient Assistance Programs

Manufacturer-based programs and charitable programs differ in what is supported and who is eligible. Manufacturer-sponsored copay assistance programs typically provide support for a specific drug; however, Medicare beneficiaries are not typically eligible for these programs. In contrast, both patients with private insurance and Medicare beneficiaries can be supported by charitable copay assistance foundations. These are funded by both private donations and, to a larger extent, manufacturers8; however, manufacturers cannot provide direct support for specific drugs through a charitable foundation but, instead, can donate to disease-specific funds that cover all drugs for that disease, including the company’s product(s).

On the surface, copay assistance programs provide a path to access and affordability for patients; however, some contend that by reducing cost sharing without addressing the problem of high drug costs, these programs not only fail to solve the problem of access to quality care, but perpetuate it. Shielding the patient from drug costs could minimize political pressure to address costs and facilitate greater use of drugs, which raise total health care expenditures while increasing company profits. Given the controversy over these programs in general, as well as the rapid evolution of cancer therapy and the well-documented financial hardship our patients face, we must better understand the impact of copay assistance programs in oncology and the role of oncologists and researchers in addressing these challenges.

Available data suggest that substantial numbers of patients use copay assistance programs. The lobbying arm of the pharmaceutical industry, PhRMA, states on its Web site that its Partnership for Prescription Assistance program has helped nearly 9.5 million people.9 One of the largest charitable copay assistance foundations, the Patient Access Network Foundation, reports that from 2011 to 2015 the foundation helped 834,819 patients by providing $2.1 billion in support for medication-related out-of-pocket costs.10 The Patient Advocate Foundation reports providing 25,330 patients with copayment assistance in 2015, with 64% of those being Medicare beneficiaries.11 The number of patients who receive assistance is often published by charitable foundations, but those data are not easily obtained from manufacturer-sponsored plans. In a recent study of 24 such plans, none provided usage data.12

Recent opinion pieces in both the lay and academic press have argued that these programs potentially encourage higher prices over time.8,13,14 The primary argument against copay assistance programs is that they support high drug prices by removing the patient’s financial disincentive for use. This is based on the concept of cost sharing by which insured patients remain financially liable for a portion of their health care costs. As demonstrated by the RAND Health Insurance Experiment of 1982, when patients pay out of pocket for a portion of their health care, they use fewer health services than patients who receive free care.15 Modern insurance design relies heavily on cost sharing, with rising premiums and deductibles, and a growing incidence of tiered formularies that charge higher copays for expensive, nongeneric drugs, including oral anticancer therapy.1 Cost sharing has become a prominent part of insurance design not only because of rising prices, but because, in theory, having a financial stake in their care could encourage greater patient engagement in treatment decisions and discourage the use of low-value health care.

Some argue that copay assistance programs remove that disincentive. For example, an oncologist may prescribe an expensive oral drug for a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer as the fifth line of therapy. That drug has questionable benefit and a risk of toxicity in this heavily treated patient. A high copay might trigger an otherwise difficult conversation about the value of the drug for that patient. Over time, high copays might also increase patient and provider concerns about pharmaceutical industry drug pricing and translate into support for political action to address drug costs.13 With financial assistance, however, patients are shielded from high out-of-pocket costs and have less incentive to protest drug prices. Without patient exposure to financial consequences of treatment decisions, both patients and physicians might pursue interventions that have marginal reported benefit, regardless of value. Subsequently, manufacturers have a free pass to charge more, have insurers cover the majority of costs, and provide assistance for whatever portion of costs insurers decline to cover.14 An infamous example outside of oncology is the pricing practices of Mylan, the manufacturer of EpiPen, which raised the epinephrine injector’s price by $500 since 2007. Rather than lowering its price when insurers were unwilling to cover the full price hike, Mylan now offers patients up to $300 in copay coupons.16 Such practices, some argue, allow manufacturers to circumvent insurance benefit design that is meant to keep costs low for the health care system by decreasing utilization.13

Copay assistance programs might also exacerbate disparities that result from unequal awareness of and access to financial assistance. Little is known about how the often complicated application process for manufacturer-sponsored programs hinders applicants, particularly those with lower literacy.17 This process can require a wide array of application materials, including pay stubs, tax returns, and verification of citizenship.12 Little is known about the degree to which these programs reach all eligible, low income, or underinsured patients. In short, copay assistance programs are viewed by some as facilitating low-value care, providing inconsistent assistance, and sustaining the high costs of care.

But to what extent are the above issues applicable to oncology? Nearly two thirds of copay assistance programs provide assistance for drugs that have less expensive, equally effective alternatives available, but what of the remaining one third of programs?18 This is where particular attention should be paid to anticancer drugs, most of which do not have a less expensive, equally effective alternative. If, as of today, patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia could no longer access copay assistance programs for imatinib, for example, they would immediately incur high out-of-pocket costs and be at risk for stopping treatment with a life-saving drug. Higher copays for imatinib were found to convey a 70% greater risk of nonadherence to the drug.19 In addition, patients who were prescribed imatinib who lacked subsidies for out-of-pocket costs were more likely to delay initiation of the drug.20 These findings, among others, suggest an association between higher cost sharing and nonadherence with anticancer therapy, even when cost sharing is relatively modest (< $100/mo).21-23 A generic form of imatinib has entered the market so that patients with high cost sharing for the branded pill could consider this alternative; however, initial data suggest that modest price reductions might not be enough to overcome cost-related nonadherence.24 In a setting where lower-cost alternatives do not exist, copay assistance programs may play an important role in promoting affordability and adherence.

Promoting cost sharing is likely to decrease use of both high-value and low-value care. For patients who are prescribed a high-value cancer drug, cost sharing arguably represents an unethical barrier to appropriate care. As oncologists, we often prescribe expensive treatment and expect our patients to receive it. Yet, evidence suggests that more patients than we realize are nonadherent because of cost.19-23 We have an obligation to be reasonable stewards of societal resources, but we have an overarching fiduciary responsibility to serve our patients’ interests. In many cases, high-cost therapy is medically indicated and we should help patients to avoid out-of-pocket costs that can lead to depleted retirement savings or personal bankruptcy.25,26 We cannot advocate for removal of assistance programs until alternative means to ensure access and prevent financial hardship are established.

Even if we agree that copay assistance programs might support higher prices in the long term, what can we do in the clinic until prices are lower? Recognizing the paradox that is posed by copay assistance programs, we recommend pursuing two paths that are not mutually exclusive: First, as individual clinicians, we have no choice but to identify financial assistance for patients whom we treat in clinic tomorrow, and second, as a profession, we must steadfastly pursue means to reduce dependence on copay assistance programs.

To reduce dependence on copay assistance programs, we must seek policy- and practice-level solutions. First, from a policy perspective, the pharmaceutical industry must price drugs more on the basis of true marginal value and less on the price of the last drug to enter the market.27 Innovation is needed and should be incentivized, but profiting over a system with few checks on price escalation should not. Second, similar to the practice in nearly all national health systems, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services should be allowed to negotiate lower drug prices with manufacturers.28 Third, we must advocate for payers to eliminate cost sharing for high-value interventions. Value-based insurance design might go a long way in decreasing financial burden on our patients.29 Oncologists should take the lead in helping to define high-value cancer care, where access for all who are in need should be the priority. Fourth, we must call for greater transparency from patient financial assistance programs, especially those that are manufacturer sponsored. These programs could be more effective by targeting patients who have the greatest financial need and by expanding coverage to broad-based disease funds rather than a particular drug.30,31

At the practice level, we can intervene to reduce dependence on copay assistance programs. First, we must have more effective and more frequent goals of care discussions with our patients. These discussions reduce aggressive care at the end of life, reduce costs, and, most importantly, serve to align care with patients’ preferences.32 Second, we should consistently identify patients who are experiencing financial strain. Validated patient-reported measures can screen for treatment-related financial strain,33 yet even such simple questions as, “Do you have trouble affording your care?” can trigger conversations to identify resources early in a patient’s treatment course, identify lower-cost alternatives when available, and, when appropriate, consider a trade-off between treatment and lower financial burden.34 Studies suggest that cost discussions between patients and physicians occur infrequently, but when they do occur, in the majority of cases, costs are reduced without changing treatment.35 Third, we must focus on care that delivers the greatest benefit at the lowest cost, and we need to do so with regard to therapy, diagnostics, and use of inpatient and emergency services.36,37

In summary, copay assistance programs are a Band-Aid solution for an imperfect system. Especially in oncology, little is known about who they help and how they might impact drug use and costs. At least three areas of research can help crystalize the role of these programs. First, research should determine whether eliminating cost sharing for high-value interventions decreases dependence on copay assistance programs, and, importantly, whether reducing cost sharing has a net impact on health care expenditures. Second, important questions related to access to assistance and health disparities remain unanswered. Research should describe patients who apply for and receive financial assistance and highlight patients who might be eligible but who never apply. Third, we should evaluate the impact of copay assistance programs on cost discussions, financial burden, and the patient–doctor relationship.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

S.Y.Z. is supported by National Cancer Institute Grant No. R42-1R42CA210699-01.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Patient Financial Assistance Programs: A Path to Affordability or a Barrier to Accessible Cancer Care?

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

S. Yousuf Zafar

Employment: Novartis (I)

Stock or Other Ownership: Novartis (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, Vivor, Family Reach Foundation, AIM Specialty Health, SamFund

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech

Jeffrey M. Peppercorn

Employment: GlaxoSmithKline (I)

Stock or Other Ownership: GlaxoSmithKline (I)

Research Funding: Pfizer

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation Employer health benefits survey. http://kff.org/health-costs/report/2016-employer-health-benefits-survey/

- 2.Bach PB. New math on drug cost-effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1797–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1512750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narang AK, Nicholas LH. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. JAMA Oncol. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4865. [epub ahead of print on November 23, 2016] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, et al. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: A population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1608–1614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1732–1740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:980–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perrone F, Jommi C, Di Maio M, et al. The association of financial difficulties with clinical outcomes in cancer patients: Secondary analysis of 16 academic prospective clinical trials conducted in Italy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:2224–2229. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elgin B, Langreth R. How big pharma uses charity programs to cover for drug price hikes: A billion-dollar system in which charitable giving is profitable. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-05-19/the-real-reason-big-pharma-wants-to-help-pay-for-your-prescription

- 9.PhRMA Access to medicines: Patient assistance. http://www.phrma.org/advocacy/access/patient-assistance

- 10.Resnick HE, Barth B, Klein D. Charitable assistance among economically vulnerable cancer patients: Patient access network foundation summary statistics 2011-2015. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22:SP450–SP457. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patient Advocate Foundation Patient data analysis report. http://www.patientadvocate.org/pdar/2015_PDAR.pdf

- 12.Zafar SY, Peppercorn J, Asabere A, et al. Transparency of industry-sponsored oncology patient financial assistance programs using a patient-centered approach. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e240–e248. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.017509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ubel PA, Bach PB. Copay assistance for expensive drugs: A helping hand that raises costs. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:878–879. doi: 10.7326/M16-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dafny LS, Ody CJ, Schmitt MA. Undermining value-based purchasing—Lessons from the pharmaceutical industry. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2013–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brook RH, Ware JEJ, Jr, Rogers WH, et al. Does free care improve adults’ health? Results from a randomized controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1426–1434. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312083092305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollack A. Mylan to offer some patients aid on cost of EpiPens, The New York Times, August 25, 2016:B4.

- 17.Choudhry NK, Lee JL, Agnew-Blais J, et al. Drug company-sponsored patient assistance programs: A viable safety net? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:827–834. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross JS, Kesselheim AS. Prescription-drug coupons—No such thing as a free lunch. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1188–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1301993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, et al. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:306–311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.9123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winn AN, Keating NL, Dusetzina SB. Factors associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor initiation and adherence among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4323–4328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hershman DL, Tsui J, Meyer J, et al. The change from brand-name to generic aromatase inhibitors and hormone therapy adherence for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju319. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2534–2542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zullig LL, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. Financial distress, use of cost-coping strategies, and adherence to prescription medication among patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:60s–63s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kodjak A. Modest price cut expected for generic version of cancer pill Gleevec. http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/02/01/465139901/generic-gleevec-imatinib-savings-will-be-modest

- 25.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143–1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard DH, Bach PB, Berndt ER, et al. Pricing in the market for anticancer drugs. J Econ Perspect. 2015;29:139–162. doi: 10.1257/jep.29.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan R, Peppercorn J, Sikora K, et al. Delivering affordable cancer care in high-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:933–980. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chernew ME, Rosen AB, Fendrick AM. Value-based insurance design. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:w195–w203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.w195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard DH. Drug companies’ patient-assistance programs—Helping patients or profits? N Engl J Med. 2014;371:97–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1401658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Office of Inspector General Department of Health and Human Services Supplemental special advisory bulletin: Independent charity patient assistance programs. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2014/05/30/2014-11769/supplemental-special-advisory-bulletin-independent-charity-patient-assistance-programs

- 32.Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2060–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1013826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120:3245–3253. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure—Out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1306826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zafar SY, Chino F, Ubel PA, et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ABIM Foundation Choosing wisely: Ten things physicians and patients should question. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-society-of-clinical-oncology/

- 37.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. American society of clinical oncology statement: A conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment options. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2563–2577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]