Abstract

PURPOSE

To identify potential gaps in attitudes, knowledge, and institutional practices toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) patients, a national survey of oncologists at National Cancer Institute–Designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers was conducted to measure these attributes related to LGBTQ patients and desire for future training and education.

METHODS

A random sample of 450 oncologists from 45 cancer centers was selected from the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile to complete a survey measuring attitudes and knowledge about LGBTQ health and institutional practices. Results were quantified using descriptive and stratified analyses and by a novel attitude summary measure.

RESULTS

Of the 149 respondents, there was high agreement (65.8%) regarding the importance of knowing the gender identity of patients, which was contrasted by low agreement (39.6%) regarding the importance of knowing sexual orientation. There was high interest in receiving education regarding the unique health needs of LGBTQ patients (70.4%), and knowledge questions yielded high percentages of “neutral” and “do not know or prefer not to answer” responses. After completing the survey, there was a significant decrease (P < .001) in confidence in knowledge of health needs for LGB (53.1% agreed they were confident during survey assessment v 38.9% postsurvey) and transgender patients (36.9% v 19.5% postsurvey). Stratified analyses revealed some but limited influence on attitudes and knowledge by having LGBTQ friends and/or family members, political affiliation, oncology specialty, years since graduation, and respondents’ region of the country.

CONCLUSION

This was the first nationwide study, to our knowledge, of oncologists assessing attitudes, knowledge, and institutional practices of LGBTQ patients with cancer. Overall, there was limited knowledge about LGBTQ health and cancer needs but a high interest in receiving education regarding this community.

INTRODUCTION

The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) community, also referred to as sexual and gender minorities (SGMs),1 is a diverse and medically underserved population2-5 that is often marginalized in a predominantly hetero- and cisgender-normative society. Despite the overwhelming evidence of cancer disparities related to age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, social class, disability, and geographic location,6,7 there have been limited efforts to address cancer disparities by sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). Although estimates for the size of LGBTQ communities vary, studies have reported that 3.4% to 12% of the adult population in the United States identifies as LGBTQ.8-10

The sparse but growing body of evidence demonstrates the LGBTQ population is associated with increased risk and poorer outcomes for certain cancers.1,10-12 Despite the increased risk, the LGBTQ population is less likely to engage in early detection and cancer screening10,13-15 and often engages in behaviors associated with increased cancer risk, including elevated rates of smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and nulliparity (among SGM assigned female at birth); anal receptive sex (among SGM assigned male at birth); and lower rates of exercise.1,16-20 With respect to health care experiences, LGBTQ populations have reported lower satisfaction with cancer care treatment21,22 and higher rates of psychological distress in survivorship,22 are less likely to have insurance coverage,23,24 and report higher rates of perceived discrimination in the health care setting.25-27 The cumulative evidence suggesting increased cancer risk and poorer outcomes among the LGBTQ community has direct translation implications. Specifically, providers with increased knowledge and understanding of the LGBTQ community will enable delivery of precision health care for primary, secondary, and tertiary preventions.

Because cancer disparity in the LGBTQ community is a largely ignored public health issue,12 there is a gap in LGBTQ-specific evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and best practice behaviors across the cancer care continuum from prevention to survivorship. In addition to having a welcoming and inclusive environment, providers should provide culturally sensitive and clinically knowledgeable care to LGBTQ patients. To generate relevant curriculum and guidelines addressing cancer disparities in LGBTQ patients, an assessment must be conducted to identify needs and gaps among providers. As such, we conducted a national survey of oncologists at National Cancer Institute (NCI)–Designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers to measure attitudes, knowledge, institutional practice behaviors, and interest in education on the care of LGBTQ patients with cancer.

METHODS

Study Population

Using random sampling from a third-party provider (Redi-Data, Fairfield, NJ), 450 oncologists from 45 NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers (as of January 2016) were selected from the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile. No stratification was conducted for the random sampling, but equal numbers of oncologists across the 45 cancer centers was requested. The AMA Physician Masterfile is the only national database of licensed practicing physicians in the United States. At the time of the random sampling, the AMA Physician Masterfile listed 15,443 health care providers, excluding residents, fellows, and oncologists whose primary position was listed as teaching, administrative, and locum tenens or unclassified, because these individuals are less likely to provide clinical care to patients on a regular basis or at all. We excluded the Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, FL), because we previously conducted a pilot study among these oncologists.28

The 450 oncologists were mailed a paper survey in January 2016 with a prepaid self-addressed return envelope. An optional link for a Web-based version of the survey was also provided. To encourage survey completion, a $20 bill was included in the envelope. The survey was anonymous, and no identifiers were collected. We used a three-wave mailing (ie, the Dillman method29), which included the initial mailing and two reminder postcards to complete the survey sent at 2 and 4 weeks after the initial mailing. The study was deemed exempt (category 2) by the institutional review board (Advarra, Columbia, MD).

Survey Measures

The details of the survey have been published elsewhere28,30 and are provided in the Appendix (online only). Briefly, the survey was developed based on previously published surveys on SGM health31-37 and was further vetted and revised by our group through a cognitive debriefing process with three oncologists and our team of researchers. The survey included 12 attitude items, six knowledge items, three items about institutional practices, 18 demographic items, and two postsurvey confidence items about providers’ knowledge regarding LGB health and transgender health. Some questions inquired separately about LGB patients versus transgender patients. The attitudes and knowledge measured responses on a five-level Likert scale: strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, or strongly agree. Respondents could also select don’t know or prefer not to answer. In addition, there were three open-ended questions eliciting additional comments to describe personal experiences treating LGBTQ patients, reservations about treating LGBTQ patients, and suggestions for improving cancer care for LGBTQ patients. Respondents were also provided with space for additional comments. Responses from the open-ended question are not included in the current analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and SDs, were used to quantify survey responses. Demographics were listed in tabular form (Table 1), and the attitudes, knowledge, and practice results are presented graphically (Figs 1-3) and in tabular form (Appendix Tables A1-A4, online only). A paired samples t test was conducted to determine whether confidence in knowledge of LGB and transgender health issues changed from the start to the end of the survey.

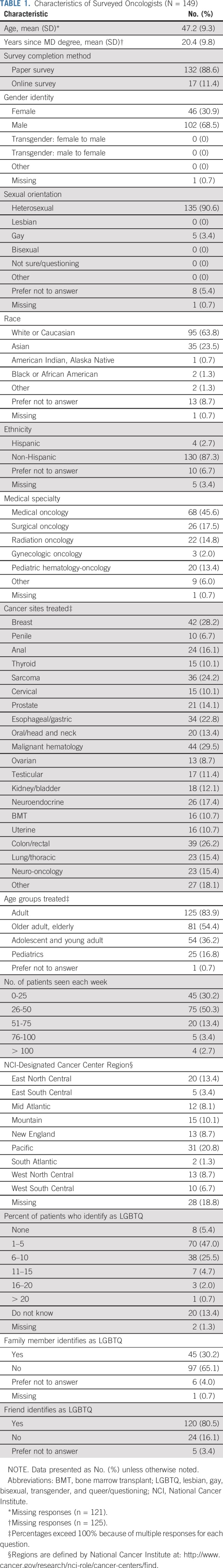

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Surveyed Oncologists (N = 149)

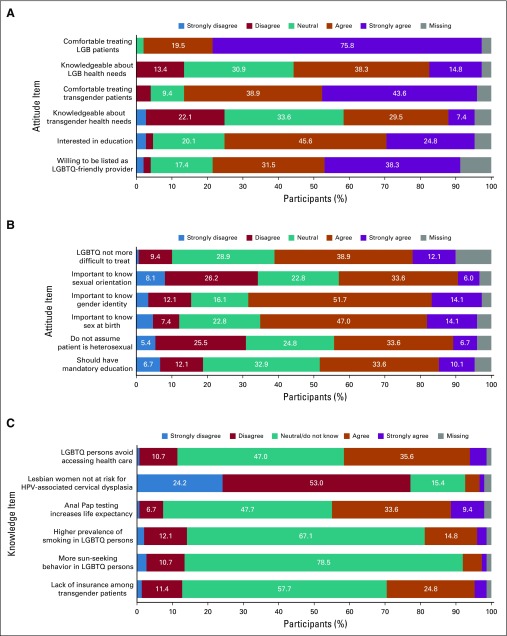

FIG 1.

Participant responses to (A, B) attitude items, and (C) knowledge items. Responses less than 5% are not labeled on the figure. All numbers and percentages are presented in Tables A1 and A2. HPV, human papillomavirus; LGBTQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning.

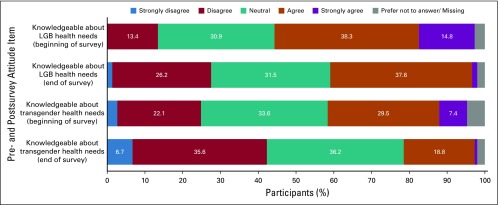

FIG 3.

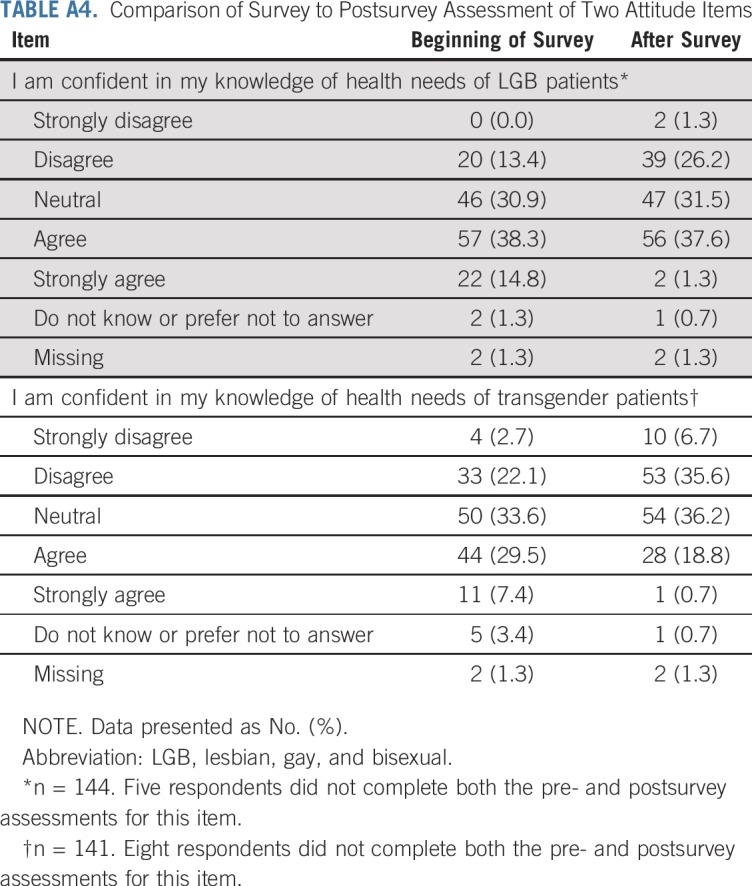

Attitude items beginning and end of survey. Responses less than 5% are not labeled on the figure. All numbers and percentages are presented in Table A4. LGB, lesbian, gay, bisexual.

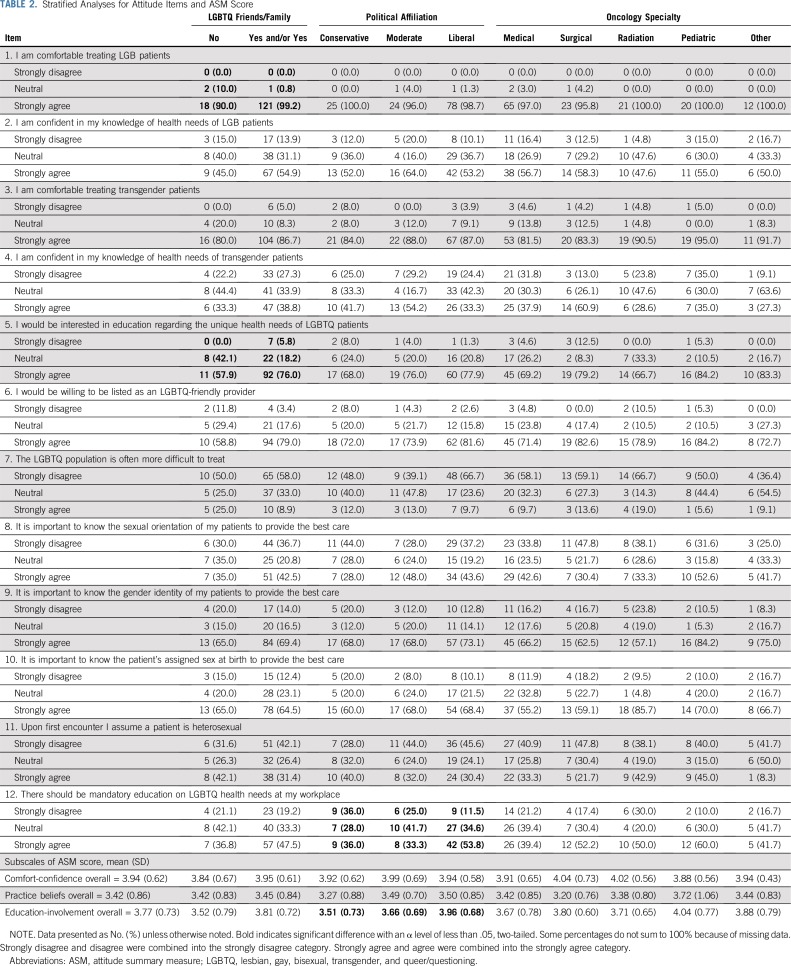

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to determine the validity and factor structure of the attitude items using principal axis factoring and varimax rotation. Two items that did not meet factor loading criteria of 0.40 or greater were removed (assume patient is heterosexual and LGBTQ patients are more difficult to treat). The final exploratory factor analysis indicated three factors (Eigenvalues > 1.62) representing comfort-confidence (items 1 to 4 in Table 2; factor loadings, 0.56 to 0.83; α = 0.76), practice beliefs (items 8 to 10 in Table 2; factor loadings, 0.61 to 0.94; α = 0.76), and education-involvement (items 5, 6, and 12 in Table 2; factor loadings, 0.51 to 0.78; α = 0.62). Within the identified factors we calculated an attitude summary measure (ASM) score, which is the average of the items within each factor.

TABLE 2.

Stratified Analyses for Attitude Items and ASM Score

Stratified analyses were performed to assess a priori differences in survey responses by demographic subgroups, including friends and/or family members identifying as LGBTQ, political affiliation, oncology specialty, number of years since graduation, and region of the country. For region of the country, we collapsed the surveyed nine regions defined by the NCI38 into Northwest, Midwest, South, and West, as defined by the US Census Bureau.39 For the stratified analyses, Pearson’s χ2 was used to determine differences in individual attitudes and knowledge across the demographic subgroups. Pairwise analyses were conducted when significant differences were found among three or more subgroups. Two factorial analyses of variances were conducted to assess main effects and interaction effects for education-involvement and practice beliefs by comfort-confidence and total knowledge.

RESULTS

Demographics

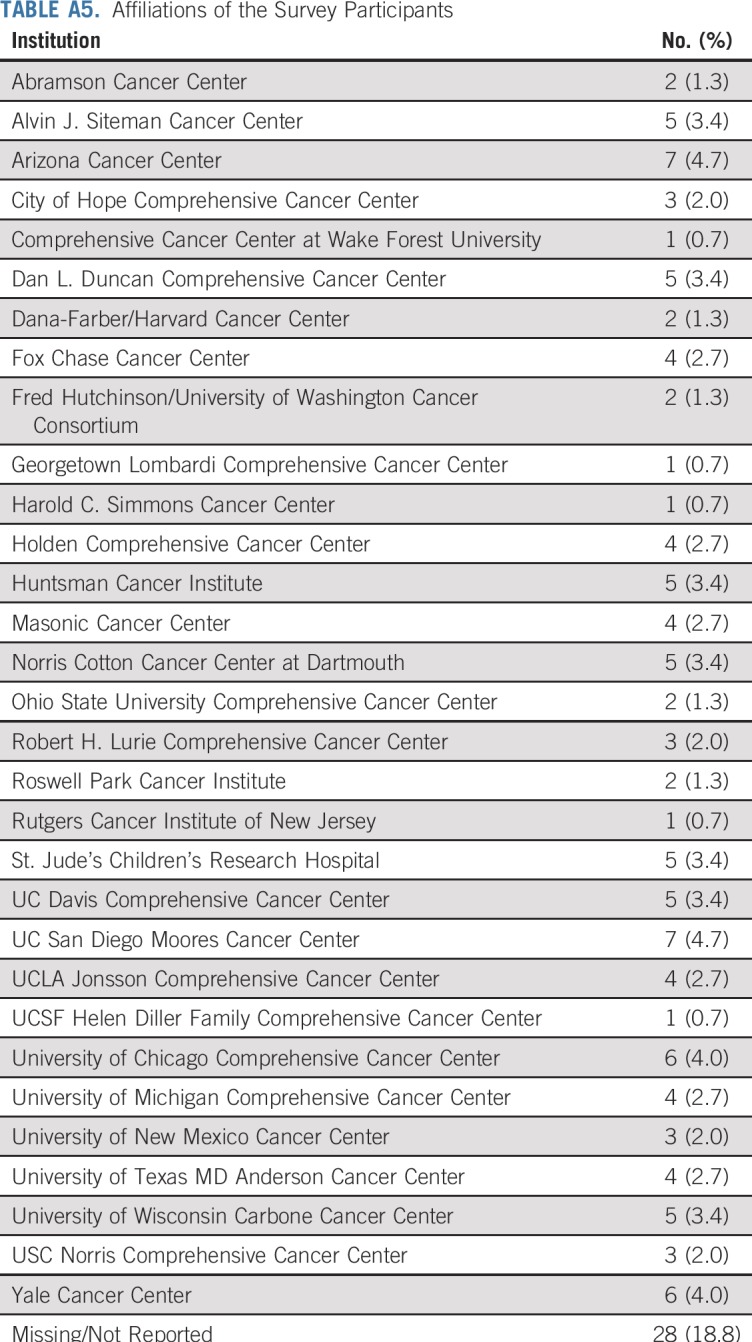

Of the 450 oncologists contacted, 149 participated, for a 33.1% response rate (Table 1). The majority of respondents identified as male (68.5%), white (63.8%), non-Hispanic (87.3%), and heterosexual (90.6%). Males and females were considered cisgender because they did not self-report as a transgender individual in the gender category. Medical oncologists represented 45.6% of the respondents, and 83.9% of respondents primarily treated adult patients (age 40 to 64 years). Using the regions defined by the NCI, the regions with the lowest percentage of respondents were South Atlantic (1.3%), East South Central (3.4%), and West South Central (6.7%). Forty-seven percent of respondents reported that 1% to 5% of their patients identified as LGBTQ, and 65.1% reported that they did not have a family member who identified as LGBTQ. The cancer center affiliations of the respondents are presented in Appendix Table A5.

Attitudes, Knowledge, and Institutional Practices

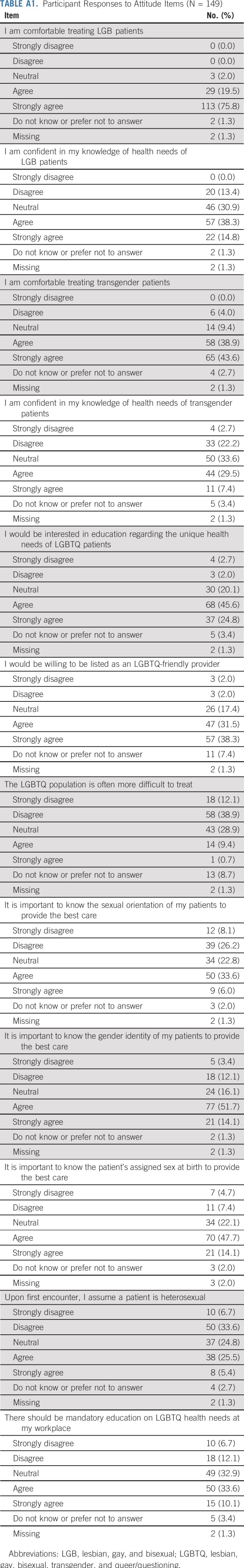

Among self-reported responses for attitudes, 95.3% reported they were comfortable (agree and strongly agree) treating LGB patients, yet only 53.1% reported they were confident in their knowledge of the health needs of LGB patients (Fig 1A). By comparison, the percentage of oncologists comfortable treating transgender patients dropped to 82.5%, and only 36.9% reported they were confident in their knowledge of the health needs of transgender patients. Among the attitudes related to disclosure, 34.3% reported it was not important (strongly disagree and disagree) to know the sexual orientation of their patients to provide the best care, and 15.5% reported it was not important to know the gender identity of patients. With respect to education, 70.4% were interested (agree and strongly agree) in education regarding the unique health needs of LGBTQ patients (Fig 1A), and 43.7% believed there should be mandatory education about LGBTQ health needs in their workplaces (Fig 1B).

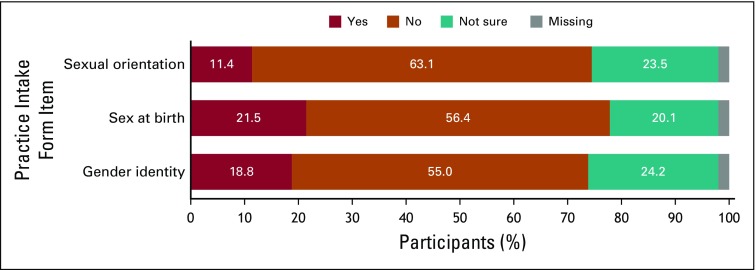

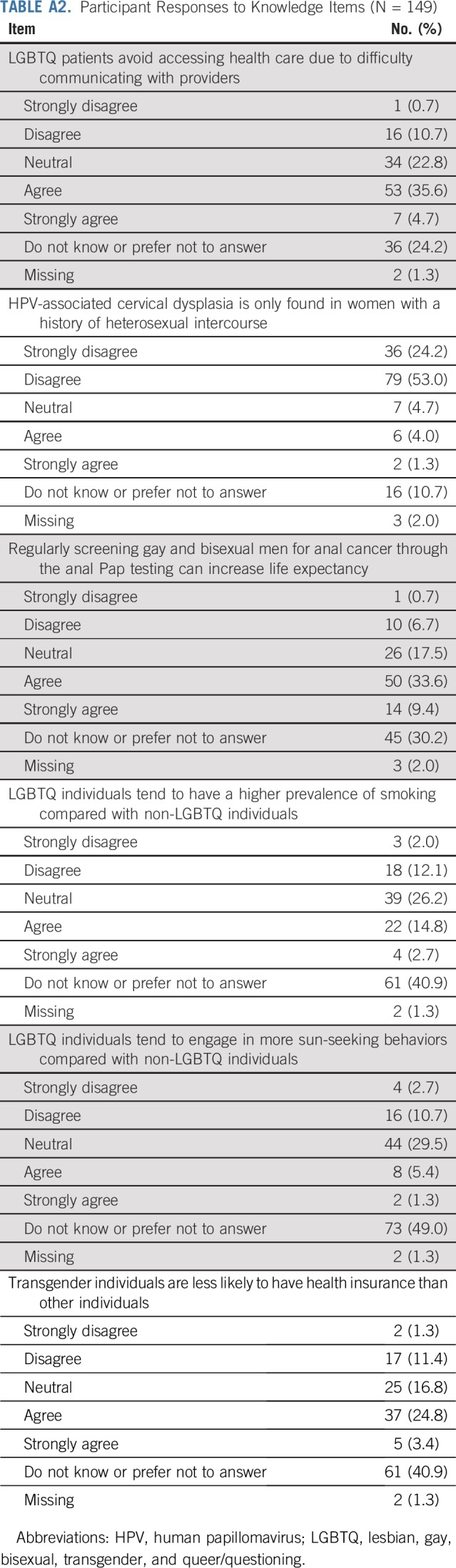

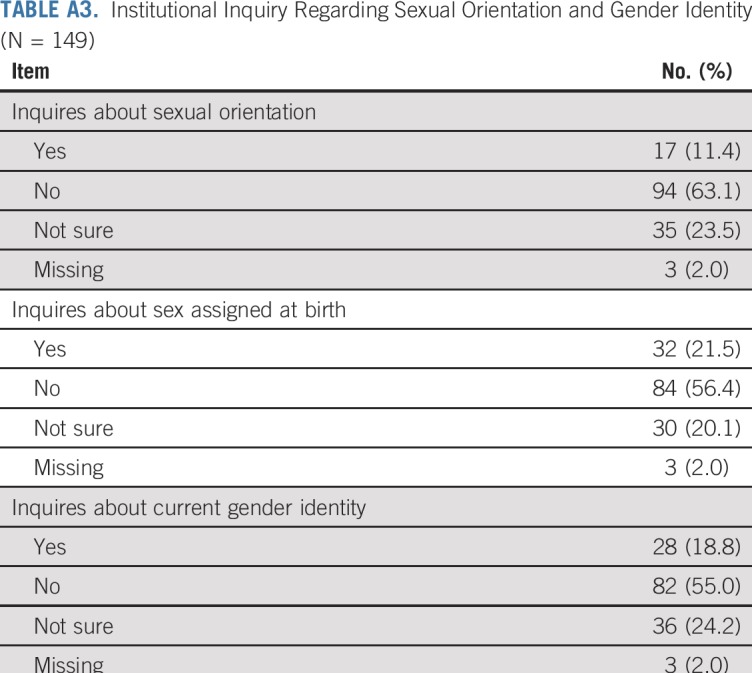

A subset of knowledge (Fig 1C) questions yielded high percentages of “neutral” and “do not know or prefer not to answer” responses. For example, the question asking whether regularly screening gay and bisexual men for anal cancer through anal Pap testing can increase life expectancy yielded a “neutral” and “do not know or prefer not to answer” response among 17.5% and 30.2% of respondents, respectively. Although studies have reported a higher prevalence of smoking among LGBTQ individuals17,18 compared with non-LGBTQ individuals, 26.2% and 40.9% of responses were “neutral” and “do not know or prefer not to answer,” respectively. Despite evidence that LGBTQ individuals tend to engage in more sun-seeking behaviors40 than heterosexual and cisgender individuals, 29.5% and 49.0% of responses were “neutral” and “do not know or prefer not to answer,” respectively. Among the practice items (Fig 2), 63.1% responded that institutional intake forms did not inquire about a patient’s sexual orientation, 54.4% did not inquire about a patient’s sex at birth, and 55% did not inquire about current gender identity.

FIG 2.

Institutional inquiry regarding sexual orientation and gender identity. Responses less than 5% are not labeled on the figure. All numbers and percentages are presented in Table A3.

Postsurvey Attitudes

In the survey assessment, 53.1% (mean, 3.12; SD, 0.87) were confident (strongly agree and agree) in their knowledge of health care needs among LGB patients (Fig 3), which decreased to 38.9% (mean, 3.56; SD, 0.91; P < .001 for paired differences). Similarly, 36.9% (mean, 3.18; SD, 0.97) were confident in their knowledge of health care needs among transgender patients in the survey assessment, which decreased to 19.5% (mean, 2.71; SD, 0.88; P < .001).

Subgroup Analyses

For the stratified analyses (Tables 2 and 3), having LGBTQ friends or family was associated with greater comfort with LGB individuals and interest in education on LGBTQ health needs (Table 2; P = .008 and P = .045, respectively). Political affiliation was associated with agreement that LGBTQ individuals have a higher prevalence of smoking (Table 3; P = .029). Political moderates were significantly more likely to agree LGBTQ individuals have a higher prevalence of smoking (28.0%) compared with liberals (17.7%; P = .007), but only marginally higher than conservatives (12.0%; P = .074). Political affiliation was also associated with agreement in mandatory education (Table 2; P = .047), with liberals reporting significantly higher agreement (53.8%) versus conservatives (36.9%; P = .019) but not significantly higher than moderates (33.3%). There were significant mean differences between provider political affiliation for the education-involvement subscale (P = .010), such that liberals had a higher average score (mean, 3.96; SD, 0.68) versus conservatives (mean, 3.51; SD, 0.73) and moderates (mean, 3.66; SD, 0.69). Additional subgroup analyses were performed by years since medical school graduation on the basis of the median value split (17.5 years) and NCI region (Tables A6 and A7).

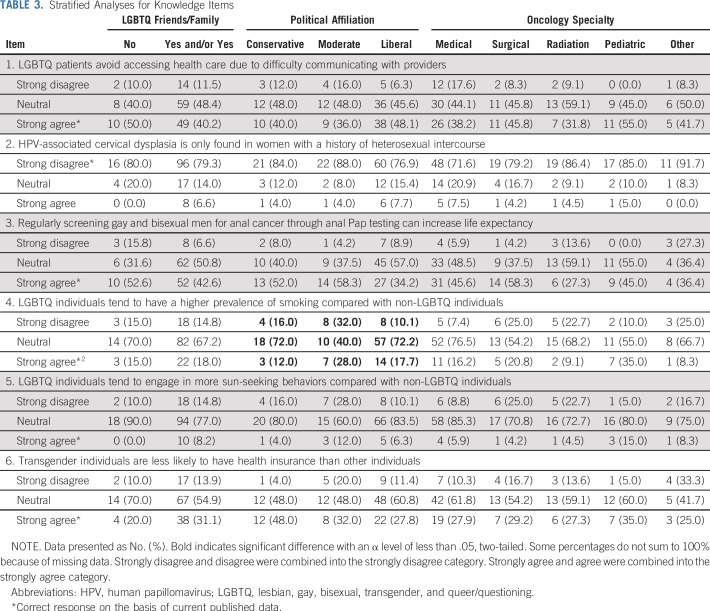

TABLE 3.

Stratified Analyses for Knowledge Items

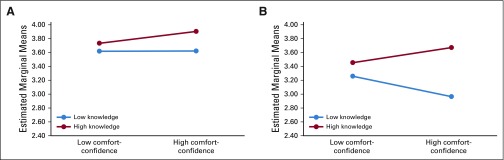

Factorial Analyses of Variance

Greater knowledge was associated with higher practice belief scores (P = .004), but comfort-confidence was not (P = .803). The interaction between higher comfort-confidence and knowledge was marginally associated with greater practice belief scores (P = .099; Fig A1). The model for education-involvement was not significant (P = .279).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used random sampling to identify oncologists from 45 NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers to assess attitude, knowledge, institutional practices, and desire for education/training regarding the care of LGBTQ patients with cancer. We found a high interest in receiving education regarding the unique health needs of LGBTQ patients and an overall limited knowledge about LGBTQ health and cancer needs. Our analyses also revealed a significant decrease from survey assessment to postsurvey assessment for confidence in knowledge for both LGB health needs and transgender health needs. We also noted a high agreement (65.8%) regarding the importance of knowing gender identity, which was contrasted with a low agreement (39.6%) regarding the importance of knowing sexual orientation. Stratified analyses by having LGBTQ friends and/or family members, political affiliation, oncology specialty, years since graduation, and region of the country of the respondents revealed some but limited influence for attitudes and knowledge regarding LGBTQ patients with cancer.

This study is an expansion of a prior published analysis conducted at a single NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center that also noted gaps in knowledge regarding the care of LGBTQ patients with cancer and found the majority of respondents were comfortable treating this population, were willing to be listed as an LGBTQ-friendly provider, were interested in receiving education about the LGBTQ care, and understood this group had unique health needs.28 Taken together, the cumulative evidence of 257 oncologists from 46 cancer centers provides the first nationwide assessment, to our knowledge, of physicians about their knowledge, attitudes, and institutional practice behaviors of LGBTQ patients with cancer. Such data provide crucial evidence to develop both culturally sensitive and clinically knowledgeable curriculum and guidelines addressing cancer disparities in LGBTQ patients across the cancer care continuum. Professional membership societies have published policy statements calling for provider education and training to address cancer disparities in the LGBTQ community.10,41 Providers with a general awareness and understanding of LGBTQ issues will provide improved quality of care for LGBTQ patients.42 As noted in this study, there was high interest in receiving education about LGBTQ health needs and a significant postsurvey decrease in confidence regarding providers’ ability to treat LGBTQ patients. This observed decrease suggests a developed awareness of lack of knowledge, and subsequent decreased confidence, perhaps attributed to exposure to survey items related to practice intake forms inquiring about SOGI information or the high number of “do not know or prefer not to answer” responses to knowledge items. As such, the results from this study can be leveraged toward future research to develop LGBTQ-centric training and resources for the development of evidence-based competency curriculum to prepare and train the oncology workforce for cancer disparities in the LGBTQ community.

Lack of accurate statistics for cancer in the LGBTQ community is directly attributed to the deficiency of collection of SOGI information at the national, state, and institutional levels. The inclusion of SOGI questions in national surveys, registries, and patient medical records is crucial to precisely identify the demography and track the disparities of this population. More than half of the respondents in this study indicated their practice intake forms did not inquire about a patient’s sexual orientation, sex at birth, or gender identity. Moreover, only a minority (39.6%) of respondents indicated it was important to know sexual orientation, despite the majority (65.8%) agreeing the importance of knowing gender identity. These findings parallel the American Association of Medical Colleges report that the majority of providers and medical students do not believe they need to know sexual orientation.43-45 Although only a minority agreed that LGBTQ patients were more difficult to treat (10.1%), more than one third were neutral or responded “do not know or prefer not to answer” to this statement (37.6%), which may point to implicit biases that may result in lower likelihood of collecting SOGI information and a lack of inclusion of LGBTQ patients more broadly for this subset of oncologists. An inclusive and inviting clinical environment that enables providers to capture SOGI information is vital to providing patient-centered care. Moreover, the National Institutes of Health and the Institute of Medicine recognize SOGI information as a vital aspect of medical care and health research and recommend collection of this information.46,47 Because knowledge among clinicians about the specific cancer health needs of LGBTQ is low, collecting SOGI data in a standardized fashion48,49 is imperative to competently and sensitively treat this population.

This study presents a novel scale—the ASM—that was used to assess three dimensions of LGBTQ-related attitudes, including feeling comfortable and confident with LGBTQ patients’ health, interest in education and being involved with LGBTQ patients, and recognizing the importance of SOGI information on quality of care. In the current study, ASM scores revealed differences for some of the factors by political ideology and region of the country but not for having LGBTQ friends/family, oncology specialty, and years since graduation. The ASM is a brief tool that can be used by researchers, within practice settings, or in the context of education intervention evaluation as a metric to assess providers’ LGBTQ-related attitudes.

We acknowledge some modest limitations of this study. We only surveyed oncologists at NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers, and, as such, these results may not be generalizable. Future studies are needed to assess these metrics in community settings and academic centers not affiliated with NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers. With a response rate of 33.1%, this study may not be representative of all oncologists at the cancer centers surveyed. However, assuming these respondents were highly motivated, we still identified substantial knowledge gaps among this subset of oncologists. We are unable to conduct subgroup analyses by SOGI status of the oncologists because there were too few LGBTQ respondents. Last, we are unable to compare demographic characteristics between responders and nonresponders because the survey was anonymous and metadata are not available from the AMA database.

This study is the first nationwide assessment, to our knowledge, of oncologists regarding attitudes, knowledge, and practice behaviors about LGBTQ patients with cancer. Although we noted overall limited knowledge about LGBTQ health and cancer needs and lack of institutional collection of SOGI information, oncologists who responded revealed a high interest in receiving education regarding the unique health needs of LGBTQ patients. Future research will be needed to assess these metrics among other health care providers, such as allied health professionals, nurses, and advanced practice providers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the following team members for their assistance and dedication to this study: Luisa Duarte Arevalo, Meghan L. Bowman, Janella Hudson, PhD, and Lauren E. Wilson.

Appendix

SUPPLEMENTARY METHODS FOR CONTENT OF SURVEY MEASURES

The attitude questions inquired about comfort treating lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) patients, confidence in knowledge of LGBTQ health needs, interest in education about LGBTQ health needs, willingness to be listed as LGBTQ-friendly provider, level of difficulty treating LGBTQ population, importance of knowing a patient’s sexual orientation and gender identity, importance of knowing a patient’s sex at birth for care, assumption a patient is heterosexual, and necessity of mandatory education on LGBTQ health needs. The knowledge questions inquired about LGBTQ patients’ avoidance of health care because of communication challenges, relationship between human papillomavirus–associated cervical dysplasia and heterosexual intercourse, life expectancy, and anal Pap screening for gay and bisexual men, prevalence of smoking in LGBTQ individuals, sun-seeking behaviors in LGBTQ individuals, and health insurance coverage among transgender individuals. The practice behaviors questions inquired whether their institution collected patient intake data regarding sexual orientation, sex at birth, and gender identity. The demographics section collected cancer center affiliation, age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious identity, role of religion in practice and treatment of patients, presence of LGBTQ family members, presence of LGBTQ friends, political identification, licensure, years since graduation, number of patients seen weekly, percent of LGBTQ patients, specialty/subspecialty, cancer sites treated, and age population treated. To gauge whether potential changes in attitudes occurred by the completion of the survey, two postsurvey attitude questions were reassessed at the end of the survey regarding confidence in knowledge of the health needs of LGB patients and confidence in knowledge of the health needs of transgender patients.

FIG A1.

Factorial analyses of variance for (A) education-involvement and (B) practice beliefs by comfort-confidence and total knowledge composite score. The total knowledge composite score was calculated by the summing the correct knowledge items.

TABLE A1.

Participant Responses to Attitude Items (N = 149)

TABLE A2.

Participant Responses to Knowledge Items (N = 149)

TABLE A3.

Institutional Inquiry Regarding Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (N = 149)

TABLE A4.

Comparison of Survey to Postsurvey Assessment of Two Attitude Items

TABLE A5.

Affiliations of the Survey Participants

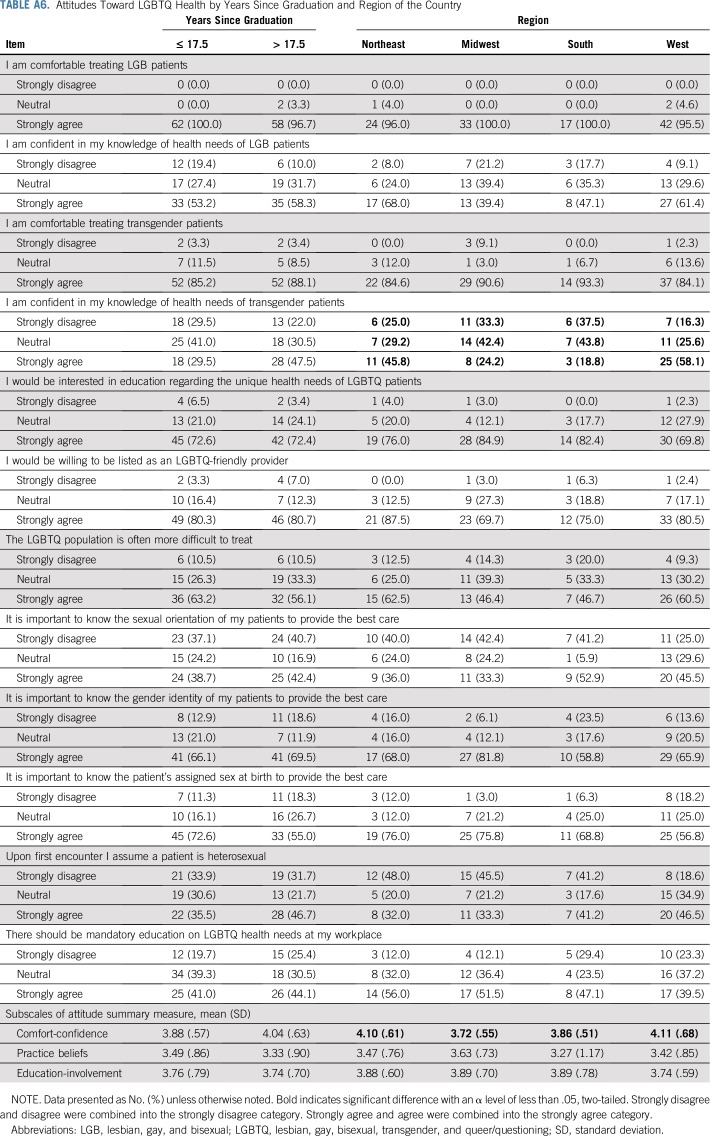

TABLE A6.

Attitudes Toward LGBTQ Health by Years Since Graduation and Region of the Country

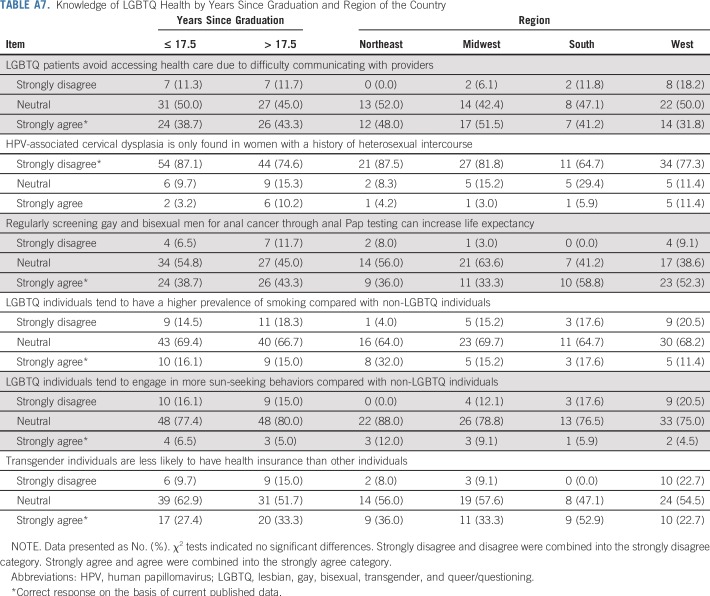

TABLE A7.

Knowledge of LGBTQ Health by Years Since Graduation and Region of the Country

Footnotes

Supported by a Miles for Moffitt Milestone Award (M.B.S., G.P.Q.) from the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer and Research Institute, and by an H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute Cancer Center Support Grant No. P30-CA76292. M.E.S. was supported by National Cancer Institute Training Grant No. R25-5R25CA090314-15.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Matthew B. Schabath, Peter A. Kanetsky, Susan T. Vadaparampil, Vani N. Simmons, Julian A. Sanchez, Steven K. Sutton, Gwendolyn P. Quinn

Provision of study material or patients: Matthew B. Schabath, Gwendolyn P. Quinn

Collection and assembly of data: Matthew B. Schabath, Steven K. Sutton, Gwendolyn P. Quinn

Data analysis and interpretation: Matthew B. Schabath, Catherine A. Blackburn, Megan E. Sutter, Peter A. Kanetsky, Steven K. Sutton, Gwendolyn P. Quinn

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

National Survey of Oncologists at National Cancer Institute–Designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers: Attitudes, Knowledge, and Practice Behaviors About LGBTQ Patients With Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Peter A. Kanetsky

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst)

Susan T. Vadaparampil

Speakers' Bureau: GlaxoSmithKline (I)

Gwendolyn P. Quinn

Research Funding: Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. : Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin 65:384-400, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, et al. : Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. Am J Public Health 103:1802-1809, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lisy K, Peters MDJ, Schofield P, et al. : Experiences and unmet needs of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people with cancer care: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Psychooncology 27:1480-1489, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthews AK, Breen E, Kittiteerasack P: Social determinants of LGBT cancer health inequities. Semin Oncol Nurs 34:12-20, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simoni JM, Smith L, Oost KM, et al. : Disparities in physical health conditions among lesbian and bisexual women: A systematic review of population-based studies. J Homosex 64:32-44, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mokdad AH, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Fitzmaurice C, et al. : Trends and patterns of disparities in cancer mortality among US counties, 1980-2014. JAMA 317:388-406, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler NE, Rehkopf DH: U.S. disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health 29:235-252, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gates GJ: How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf

- 9.Gates GJ, Newport F: Special Report: 3.4% of U.S. Adults Identify as LGBT. Gallup. http://news.gallup.com/poll/158066/special-report-adults-identify-lgbt.aspx

- 10.Graham R, Berkowitz B, Blum R, et al. : The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waterman L, Voss J: HPV, cervical cancer risks, and barriers to care for lesbian women. Nurse Pract 40:46-53, quiz 53-54, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0137. Boehmer U, Elk R: LGBT populations and cancer: Is it an ignored epidemic? LGBT Health 3:1-2, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seay J, Ranck A, Weiss R, et al. : Understanding transgender men’s experiences with and preferences for cervical cancer screening: A rapid assessment survey. LGBT Health 4:304-309, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ceres M, Quinn GP, Loscalzo M, et al. : Cancer screening considerations and cancer screening uptake for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. Semin Oncol Nurs 34:37-51, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.11.009. Tabaac AR, Sutter ME, Wall CSJ, et al: Gender identity disparities in cancer screening behaviors. Am J Prev Med 54:385-393, 2018 [Erratum: Am J Prev Med 55:943] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Althuis MD, Fergenbaum JH, Garcia-Closas M, et al. : Etiology of hormone receptor-defined breast cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13:1558-1568, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rath JM, Villanti AC, Rubenstein RA, et al. : Tobacco use by sexual identity among young adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 15:1822-1831, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamen C, Palesh O, Gerry AA, et al. : Disparities in health risk behavior and psychological distress among gay versus heterosexual male cancer survivors. LGBT Health 1:86-92, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaritsky E, Dibble SL: Risk factors for reproductive and breast cancers among older lesbians. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 19:125-131, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boehmer U, Bowen DJ, Bauer GR: Overweight and obesity in sexual-minority women: Evidence from population-based data. Am J Public Health 97:1134-1140, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hulbert-Williams NJ, Plumpton CO, Flowers P, et al. : The cancer care experiences of gay, lesbian and bisexual patients: A secondary analysis of data from the UK Cancer Patient Experience Survey. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 26:e12670, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jabson JM, Kamen CS: Sexual minority cancer survivors’ satisfaction with care. J Psychosoc Oncol 34:28-38, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchmueller T, Carpenter CS: Disparities in health insurance coverage, access, and outcomes for individuals in same-sex versus different-sex relationships, 2000-2007. Am J Public Health 100:489-495, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzales G, Blewett LA: National and state-specific health insurance disparities for adults in same-sex relationships. Am J Public Health 104:e95-e104, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Learmonth C, Viloria R, Lambert C, et al. : Barriers to insurance coverage for transgender patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 219:272.e1-272.e4, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glick JL, Theall KP, Andrinopoulos KM, et al. : The role of discrimination in care postponement among trans-feminine individuals in the U.S. National Transgender Discrimination Survey. LGBT Health 5:171-179, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reisner SL, Hughto JM, Dunham EE, et al. : Legal protections in public accommodations settings: A critical public health issue for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. Milbank Q 93:484-515, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shetty G, Sanchez JA, Lancaster JM, et al. : Oncology healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors regarding LGBT health. Patient Educ Couns 99:1676-1684, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM: Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method (ed 4). Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamargo CL, Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, et al. : Cancer and the LGBTQ population: Quantitative and qualitative results from an oncology providers’ survey on knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors. J Clin Med 6:E93, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim FA, Brown DV, Jr, Jones H: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: Fundamentals for nursing education. J Nurs Educ 52:198-203, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdessamad HM, Yudin MH, Tarasoff LA, et al. : Attitudes and knowledge among obstetrician-gynecologists regarding lesbian patients and their health. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 22:85-93, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitts RL: Barriers to optimal care between physicians and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescent patients. J Homosex 57:730-747, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed AC, Reiter PL, Smith JS, et al. : Gay and bisexual men’s willingness to receive anal Papanicolaou testing. Am J Public Health 100:1123-1129, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelley L, Chou CL, Dibble SL, et al. : A critical intervention in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: Knowledge and attitude outcomes among second-year medical students. Teach Learn Med 20:248-253, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia TC: Primary care of the lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgendered woman patient. Int J Fertil Womens Med 48:246-251, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonvicini KA, Perlin MJ: The same but different: Clinician-patient communication with gay and lesbian patients. Patient Educ Couns 51:115-122, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Cancer Institute : NCI-Designated Cancer Centers: Find an NCI-Designated Cancer Center. http://www.cancer.gov/research/nci-role/cancer-centers/find

- 39.United States Census Bureau : Geographic Terms and Concepts - Census Divisions and Census Regions. https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html

- 40.Mansh M, Katz KA, Linos E, et al. : Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA Dermatol 151:1308-1316, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griggs J, Maingi S, Blinder V, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement: Strategies for reducing cancer health disparities among sexual and gender minority populations. J Clin Oncol 35:2203-2208, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rounds KE, McGrath BB, Walsh E: Perspectives on provider behaviors: A qualitative study of sexual and gender minorities regarding quality of care. Contemp Nurse 44:99-110, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zelin NS, Hastings C, Beaulieu-Jones BR, et al. : Sexual and gender minority health in medical curricula in new England: A pilot study of medical student comfort, competence and perception of curricula. Med Educ Online 23:1461513, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuzzell L, Fedesco HN, Alexander SC, et al. : “I just think that doctors need to ask more questions”: Sexual minority and majority adolescents’ experiences talking about sexuality with healthcare providers. Patient Educ Couns 99:1467-1472, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rubin R: Minimizing health disparities among LGBT patients. JAMA 313:15-17, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cahill S, Makadon HJ: Sexual orientation and gender identity data collection update: U.S. Government takes steps to promote sexual orientation and gender identity data collection through meaningful use guidelines. LGBT Health 1:157-160, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cahill S, Makadon H: Sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in clinical settings and in electronic health records: A key to ending LGBT health disparities. LGBT Health 1:34-41, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Institute of Medicine (US) Board on the Health of Selected Populations: Collecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data in Electronic Health Records: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradford J, Cahill S, Grasso C, et al. : How to gather data on sexual orientation and gender identity in clinical settings. http://thefenwayinstitute.org/documents/Policy_Brief_HowtoGather..._v3_01.09.12.pdf