Abstract

The managers of community-based organizations that are contracted to deliver publicly funded programs, such as in the child welfare sector, occupy a crucial role in the implementation and sustainment of evidence-based interventions to improve the effectiveness of services, as they exert influence across levels of stakeholders in multitiered systems. This study utilized qualitative interviews to examine the perspectives and experiences of managers in implementing Safe Care®, an evidence-based intervention to reduce child maltreatment. Factors influencing managers’ abilities to support SafeCare® included policy and ideological trends, characteristics of leadership in systems and organizations, public–private partnerships, procurement and contracting, collaboration and coopetition, and support for organizational staff.

Keywords: Child maltreatment, evidence-based practice, institutional theory, management, resource dependency theory

Introduction

In recent decades, evidence-based interventions (EBIs) have emerged as important strategies to improve the effectiveness of publicly funded services and the well-being of families at risk for child maltreatment (Novins, Green, Legha, & Aarons, 2013). However, the implementation of EBIs in the public sector is a complicated process that can be fraught with challenges, especially for the managers of community-based organizations (CBOs) that are contracted by government entities to deliver child welfare services (Birken et al., 2017; Raffel, Lee, Dougherty, & Greene, 2013; Wike et al., 2014). These challenges also affect the sustainment of EBIs, referring to the maintenance and continued benefits of an EBI over time (Moore, Mascarenhas, Bain, & Straus, 2017). Factors influencing the capacity of CBO staff to meet contract requirements regarding EBI implementation and sustainment are wide ranging, including but not limited to organizational readiness, funding availability, com- munity connections, intervention fit, training, and long-term financial and program planning (Cooper, Bumbarger, & Moore, 2015). Studies suggest that CBO managers (i.e., CEOs and program directors) have pivotal roles in navigating these challenges to usher in and support ongoing use of innovations as their positions enable them to exert influence and foster alignment of interests and goals across levels of stakeholders in multitiered public systems (Birken et al., 2016; Birken, Lee, & Weiner, 2012; Demby et al., 2014; Kegeles, Rebchook, Tebbetts, & Arnold, 2015; Palinkas & Aarons, 2009). The attitudes and behaviors of CBO managers can also affect the success of EBI implementa- tion and sustainment (Guerrero, Padwa, Fenwick, Harris, & Aarons, 2015; Rodriguez, Lau, Wright, Regan, & Brookman-Frazee, 2018).

This study examines the perspectives and experiences of CBO managers in supporting EBIs in the child welfare sector over time. Specifically, we consider the following research question: “What do CBO managers perceive to be the most important factors impacting implementation and sustainment of an EBI in nonprofit organizations that deliver child welfare services?” Their reflections on how they and other CBO managers enter, maintain, and negotiate relationships among government administrators, peers, and staff can elucidate factors influencing EBI outcomes, such as sustainment. Greater understanding of CBO manager perspectives is crucial, as these particular stakeholders often have power to guide implementation strategy and design (Rodriguez et al., 2018) and can assist in circumventing failures in EBI implementation and sustainment. Such failures minimize the positive effects of EBIs for clients and of public resources allocated for this purpose (Aarons, Hurlburt, & Horwitz, 2011; Moore et al., 2017).

Contracting for child welfare services

In the United States, provision of child welfare services—including EBIs—often involves service delivery networks made up of government entities, such as state and county child welfare agencies, that contract with private entities, like CBOs, to deliver publicly funded services. Since the 1980s, public-sector contracts that were once based on informal, predictable, and long-standing relation- ships (Johnston & Romzek, 2008; Smith, 2010) have been increasingly transformed by the “market- ization” of procurement processes, prompting greater emphasis on competition and the growth of for-profit options, cost containment and decreased expense for government agencies, the assumption of financial risk (e.g., responsibility for cost over-runs) by CBOs and providers, and performance incentivization and outcomes (Smith, 1996, 2010).

In terms of traditional principal–agent theory, relationships between “purchasers” or “principals” (e.g., government agencies) and “sellers” or “agents” (e.g., CBOs) in a service delivery network are hierarchically organized, with government agencies delegating responsibility to CBOs for specific services (Van Slyke, 2007). For their part, CBOs tend to be undercapitalized yet are entrusted to provide labor-intensive and costly services to diverse client bases (Bunger et al., 2014; Smith, 2010). Both parties agree to contract terms delineating how CBOs are to be compensated, and their performance is evaluated. Such contractual relationships implicitly assume the existence of goal conflict and opportunistic/self-seeking behavior among CBO managers competing for a contract (Van Slyke, 2007). However, participating parties may also function cooperatively and interdependently in a stewardship capacity to jointly produce services for vulnerable populations (Johnston & Romzek, 2008; Van Slyke, 2007). When CBO managers act in this capacity, their motives ideally align with those of the principals, whereas trust, reputation, collective goals, and relational reciprocity rather than individual or organizational self-interest come to characterize the contracting relationship (Van Slyke, 2007).

The relationships assembled through and around these types of service contracts make up a service delivery network. Network stability, or the extent to which these relationships remain consistent over time, is associated with efficient, high-quality service provision. Trust between stakeholders within the network contributes to its stability (Johnston & Romzek, 2008; Smith, 2010). Other inter-related factors affecting network stability include policies, funding arrangements, and contracting processes, as well as the characteristics of individual organizations within the network, such as workforce and fiscal viability (Aarons et al., 2011; Damschroder et al., 2009). Contractual arrangements can support principal-steward arrangements via partnerships between government administrators and CBO stakeholders to build support, leadership, and local capacity to deliver EBIs and create overall network stability (Amirkhanyan, Kim, & Lambright, 2012; Bunger, 2013; Willging, Green, Gunderson, Chaffin, & Aarons, 2015). Trust and participatory engagement for planning and problem solving in contract-based relationships may facilitate successful sustainment in networked systems (Aarons et al., 2014, 2016; Green et al., 2016; Willging et al., 2015).

Guiding concepts

In general, factors affecting EBI provision in large service systems can be categorized as belonging to the “outer context” and the “inner context.” Although the outer context refers to the system level and broader environment (e.g., state, county, community) in which service delivery organizations operate, the inner context includes CBO internal operations and levels, such as teams of service providers and individual practitioners (Aarons et al., 2011; Damschroder et al., 2009). Upper-level management personnel of CBOs can offer insight into the outer context, due to the professional relationships that they likely forge with government administrators and funders, and their involvement in competing for and procuring public-sector contracts. At the same time, CBO managers can illuminate factors within the inner context, owing to their role overseeing the work of midlevel and frontline service delivery staff.

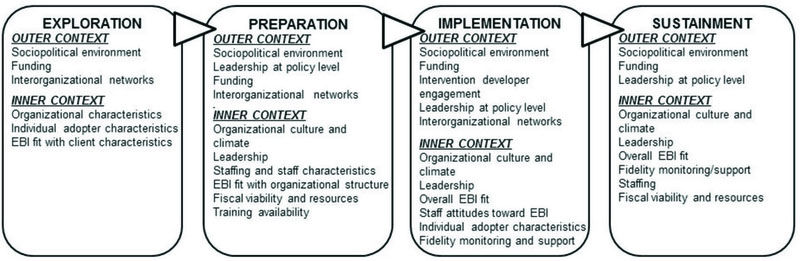

There are numerous published implementation frameworks employed across a variety of innovations and healthcare settings (Despard, 2016; Moullin, Sabater-Hernández, Fernandez-Llimos, & Benrimoj, 2015). Most approach implementation as a multiphasic process involving diverse stakeholders and influential factors at three levels: system, organization, and practitioner (Moullin et al., 2015). Core differences among frameworks relate to implementation context and type of innovation. One such framework developed for public mental health and social service settings (including child welfare) that illustrates the complexities of implementing service innovations, including the EBI discussed in this study, is the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) framework (Aarons et al., 2011). This framework separates implementation into four phases: Exploration (consideration of an innovation), Preparation (planning for implementation of the innovation), Implementation (training in and provision of the innovation), and Sustainment (maintaining the innovation with fidelity). This framework is relevant to this study because it calls attention to outer- and inner-context factors and relationships that are likely to affect public-sector EBI provision over time (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Exploration, preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment Framework

Many outer- and inner-context factors can affect implementation of EBIs in child welfare service systems. Through qualitative interviews with a combined sample of clinicians, advisors, and man- agers involved in child welfare service provision, Dufour and colleagues (2014) identified several such factors. Inner-context factors included characteristics of the implementing organization (e.g., an open and flexible organizational culture, strong EBI support from organizational leaders) and individual practitioners (e.g., openness to innovation, readiness for change). Outer-context factors centered on intervention content and training (e.g., modeling of content, intensity of intervention) and sociopolitical issues (e.g., consistency of EBI with government mandates, frequent changes in policy; Dufour et al., 2014).

Our own qualitative research on policy makers’ perspectives toward EBI implementation in the child welfare sector emphasizes the importance of building support and leadership for EBIs at the system level and within the inner context of implementing organizations (Willging et al., 2015).

Here, policy makers stressed bringing a combination of funding and contractual strategies to bear and tackling challenges affecting implementation via proactive planning and problem solving and through partnerships with CBO managers. At the same time, policy makers pointed to political, legal, and systemic pressures emanating from the outer context as key influences on EBI longevity. A second analysis of perspectives derived from policy makers, funders, and CBO managers also described the positive role of interagency collaboration among CBO leaders in supporting EBI instantiation within service systems (Hurlburt et al., 2014).

A recent mixed-method study of managers responsible for administrative or clinical oversight of EBI provision in 98 agencies directly operated or contracted by a large county-based department of mental health revealed that their positive attitudes toward an EBI resulted in a 526% increase in its sustainment (Rodriguez et al., 2018). In qualitative interviews, the managers pointed to the inter- section of inner- and outer-context factors, including intervention fit with client needs and with contract and funding requirements, workforce infrastructure at system and organization levels, and provision of ongoing training and support for practitioners, whose own attitudes also affected sustainment (Rodriguez et al., 2018). Owing to their knowledge and influence over EBI sustainment, greater understanding of how the managers of implementing organizations, such as CBOs, approach implementation and sustainment of EBIs can yield valuable insight into enhancing EBI provision in the child welfare sector.

Organizational theories, such as institutional theory and resource dependency theory, are useful for analyzing the interplay between inner- and outer-context factors affecting participation of CBO managers in networked systems and how this participation can shape decisions and actions during the EPIS phases of EBI provision. Institutional theory (Aldrich & Ruef, 2006; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Scott, 1992) posits that the actions of CBO managers (e.g., decisions to implement EBIs) are often influenced by pressures to align the norms, values, and expectations of partners from influential institutions, including government agencies and other funding organizations. Although institutional theory focuses on how organizational actors react to outer-context factors, resource dependency theory emphasizes control of resources as the driver of organizational action (Aldrich & Ruef, 2006). This theory suggests that CBO managers are likely to make decisions and form relationships to access needed resources while balancing their relative dependency on, and autonomy from, other entities in networked systems (Aldrich, 1979; Pfeffer, 1997). For example, a manager might balance the security of a subcontracting relationship with another CBO against the autonomy offered by operating independently of other CBOs. Taken together, institutional and resource dependency theories identify the range of ways in which managers may alter a CBO’s use of, or relationship with, networked resources to strategically respond to outer- and inner-context factors (Oliver, 1991, 1997). Such theories are presently under- utilized in implementation science research (Birken et al., 2017). This study draws particularly from Oliver’s (1991, 1997) fusion of institutional and resource dependency theories, which explores social pressures (i.e., institutional influences, such as legislation and funding priorities, internal organizational values, habits, and norms) and economic forces (i.e., contract arrangements, fiscal health of the organization) that jointly shape the actions of organizational decision makers throughout the phases encompassing the EPIS.

Methods

Study context

This study focuses on CBO managers involved in implementing SafeCare®, a widely studied, manualized, and highly structured home-based behavioral skills training and education EBI to reduce and prevent child maltreatment for parents of children age 0 to 5 years (Chaffin, Bard, Bigfoot, & Maher, 2012; Gershater-Molko, Lutzker, & Wesch, 2003; Lutzker, 1998). The EBI is delivered in home settings to improve parenting skills for caregivers identified as at risk, or who have been reported for child maltreatment. Implementation requires three types of professionals: (1) home visitors who deliver the EBI to caregivers, (2) coaches who conduct monthly monitoring of home visitor interactions with caregivers to ensure fidelity to the curriculum and to provide targeted mentorship in EBI practice, and (3) certified trainers who educate and coach new home visitors in the EBI model. Ideally, this three- part structure facilitates self-sustainment of SafeCare implementation by localizing training and quality control in the service system, thereby creating resilience to local workforce turnover at a relatively modest cost. The developers of SafeCare set training and certification standards. This increasingly popular EBI currently has been implemented in human service systems throughout the United States and in other countries (Birken et al., 2017; Gershater-Molko et al., 2003).

This study is part of a large-scale, prospective mixed-methods research initiative to examine SafeCare’s implementation and sustainment in 11 service systems in two U.S. states. Per the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau, the first state has approximately 3.7 million residents, 42% of whom live in rural areas. In this state, the EBI is implemented through a state-operated child welfare system with home-based services guided and contracted by the state government. In the second state, the EBI is implemented through county-operated systems with services guided and contracted by local governments. This second state features 10 urban and rural counties involved in implementing the EBI; eight of these employed the EBI in their child welfare systems, one in its social service system, and another as part of its mental health service system. The counties range in population from just over 150,000 residents to approximately 3.2 million.

During this study’s data collection timeframe, nine service systems across both states contracted with private, nonprofit CBOs to deliver the EBI. Of the remaining service systems, one contracted with a public health agency, and one did not engage in contracting but rather tried delivering the EBI as part of system activities, tasking government social workers with direct service provision. Both systems were excluded from the present study, as there were no CBO managers involved at the time of data collection. In collaboration with EBI model experts, the authors of this study classified the nine service systems by three types of sustainment status: “fully sustaining” (n = 6), “partially sustaining” (n = 1), and “not sustaining” (n = 2) according to recommendations from a systematic review of sustainment (Stirman et al., 2012).

In fully-sustaining systems, core elements of the EBI were maintained at a sufficient level of fidelity after initial implementation support had been withdrawn, and adequate capacity existed to maintain these core elements (Stirman et al., 2012). Fully-sustaining sites had trained and certified home visitors who received ongoing coaching in the EBI and were monitored for fidelity to the EBI. Partial sustainment describes a system where home visitors met only some core elements after withdrawal of initial implementation support. In the one such site, home visitors delivered the EBI to the client population but did not take part in ongoing coaching or fidelity monitoring required by intervention developers. In nonsustaining systems, the CBO staff no longer provided services in the EBI to their client population. Here, the intervention developers directed the previously trained providers to stop implementing the EBI.

Participants

We conducted 30 individual semistructured interviews and five small group interviews (five or fewer participants) with 25 CBO managers in the nine systems. These data were collected as part of the larger study of the 11 service systems, which also included interviews and focus groups with stakeholders at the system-level (i.e., state or county agency and funding organization personnel), and frontlines (i.e., home visitors, coaches, and supervisors). Data were collected at three points: Time 1 (T1; initial Implementation phase for one site; 2006–2008), Time 2 (T2; initial Implementation phase for eight sites, later Implementation/Sustainment phase for the single site referenced above; 2009–2011), and Time 3 (T3; Sustainment phase for all sites; 2012–2014). We collected data in at least one system each year across all three periods. Most data collection occurred in T3 when the nine service systems had been implementing or sustaining the EBI for a minimum of 2 years. Of the 25 participants, three participated in four interviews, two in three interviews, five in two interviews, and 15 in one interview across all three periods. Participants in this analysis were upper-level managers in the CBOs who held executive and program directorship titles. Lower- and midlevel administrative personnel and frontline service delivery staff were excluded from the data set for the present analysis, though we discuss their perspectives elsewhere (Willging et al., 2015b). The participants in this study were purposefully selected based on their positions and due to their engagements with multiple levels of stakeholders comprising the networked systems in which their CBO staff delivered the EBI.

We invited participants via phone and email. The participation rate was 96%. As illustrated in Table 1, participants were mostly women and non-Hispanic White. Most had a master’s degree, and all had some college education. All participants signed an official written informed consent document, which clearly specified that pertinent identifying features (e.g., names and locations of employment) would not be included in publications to protect their anonymity. Thus, names of states and service systems were withheld from the data reported below. The sampling method, research design, and consent procedures were approved by the Human Research Protections Program of the University of California, San Diego.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics (n=25)

| Female | 68% |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 92% |

| Asian | 4% |

| Other | 4% |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 20% |

| Education | |

| Some College | 8% |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 4% |

| Some Graduate | 8% |

| Master’s Degree | 72% |

| Doctorate | 4% |

| Unknown | 4% |

Data collection and analysis

Open-ended questions made up the semistructured interview and small-group discussion guides for T1 to T3. The interviews/discussions lasted approximately one hour and were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. Data collection during T1 focused on the Exploration, Preparation, and early Implementation phases, delving into participant perceptions about the EBI, development and adoption of implementation procedures, and reflections of inner- and outer-context factors affecting implementation, including system and organizational leadership, contracting processes, and funding.

Data collection in T2 examined how the EBI had fared within the various service systems during the Implementation phase, prompting participants to contemplate successes and challenges encountered during this period. For T3, we asked participants about the later Implementation/Sustainment phases, including inner- and outer-context factors influencing instantiation of the EBI and prospects for its sustainment. Topics broached with participants included CBO roles and partnerships in networked systems, stakeholder interactions, leadership, decision making, contracts, and policies. Although data were collected after the conclusion of the Exploration phase and at different stages of the EPIS, participants still had opportunities to discuss each phase, and their perspectives regarding each are included in the Results section where relevant.

Two research team members (Authors 2 and 4) collaborated using an iterative process to review and analyze transcripts in NVivo 10, a qualitative data analysis software (QSR International, 2012). Segments of text ranging from a phrase to several paragraphs were assigned codes based a priori on the topic areas and questions making up the interview guides (Patton, 2015). These codes centered on key sensitizing concepts from the EPIS framework (see Figure 1) and the broader implementation literature (e.g., implementation, sustainment, leadership support, and stakeholder interaction). The concepts provided “a general sense of reference” for our analysis and allowed us to analyze their salience and meaning for participants based on their own reflections on their perceptions and experiences (Patton, 2015, p. 545). Focused coding was then used to determine which concepts or themes emerged frequently and which represented unusual or particularly important issues to participants. The two team members independently coded sets of transcripts, created detailed memos that described and linked codes to each theme, and shared their work with the larger team for review. By comparing and contrasting codes with one another, we then grouped together those with similar content or meaning into broad themes linked to segments of text within the database (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Results

Several interconnected themes pertinent to our research question emerged that center on policy and ideological trends, leadership in systems and organizations, public–private partnerships, procurement and contracting processes, collaboration and co-opetition between CBOs, and support for CBO staff to implement the EBI. The first theme pertains to outer-context influences on EBI implementation, the next three themes illustrate ways that CBO managers acted to bridge outer- and inner- context factors, and the last theme attends primarily to the inner context. We include quotations representing the perceptions and experiences of participants for each theme. Some quotations were edited slightly to enhance readability. Table 2 features a timeline of EBI implementation and sustainment by EPIS phase and outer- and inner-context findings.

Table 2:

Upper-level CBO Management Perspectives by EPIS Phase

| System Type |

Exploration (Data from T1) |

Preparation (Data from T1) |

Implementation (Data from T2) |

Sustainment (Data from T2 and T3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fully

Sustaining |

Outer Context: The CBO managers act as leaders in innovating practices by participating in collaborative relationships in larger networked systems of stakeholders (e.g., government administrators, funders, colleagues at other CBOs). They take part in key committees and councils focused on child welfare and work cooperatively with other organizations to plan new initiatives. They attend presentations pertinent to EBI adoption and implementation, and they seek out funding opportunities for their CBOs. Inner Context: Upper-level management is proactive in cultivating a spirit of innovation in their CBOs by championing EBIs to staff. |

Outer Context: The CBO managers engage in frequent communication and productive working relationships with other network stakeholders, although they worry that lower-level CBO staff with useful insight into problem areas do not participate in these meetings. Managers characterize relationships with their peers at other CBOs as trusting and collaborative, and not necessarily competitive. Managers of different CBOs support one another when negotiating with other system stakeholders (e.g., government officials and funders). Co- opetition (e.g., deliberating over training capacity, competition for other funding streams, contractor-subcontractor relationships) arises but is not a continuous or dominant characteristic of relationships in the broader networked system. Inner Context: There are no major transitions in CBO leadership. Managers usher in organizational changes to support EBI (e.g., ensuring appropriate staffing, caseloads, and documentation). They help set up CBOs to deliver the EBI, but some are dismayed that preparing takes longer than anticipated. |

Outer Context: The EBI is largely implemented through established relationships between government officials and CBO managers. Contracting processes are characterized by limited competition among potential contractors. Managers remain involved with networks of other system stakeholders through frequent communication and attendance at meetings pertinent to the EBI. Managers are proactive in performing outreach to other system-level networks (e.g., government social workers) to ensure appropriateness and continuity of referrals to the EBI. Inner Context: Upper-level management of CBOs remains stable overall, despite one CBO experiencing a change in directors. Managers continue to proactively promote the EBI to cultivate buy- in among CBO staff. They remain attentive to making intra- organizational changes as related to staffing, caseloads, and documentation. |

Outer Context: The CBO managers continue networking with other system stakeholders, which helps them stay abreast of the policy changes or trends at the county, state, and national levels, and of funding opportunities. Managers collaborate with other system stakeholders to bolster support structures related to EBI provision. Managers continue to collaborate with peers at other CBOs to negotiate changing contracts. Managers are very aware that the future of provision depends on government administrators and funders who finance the EBI. Inner Context: Upper-level management in CBOs continues to be stable. However, managers now take a less active role in overseeing EBI provision, instead reporting strong support for mid-level CBO staff (e.g., trainer/coach, program manager/coordinator). They reportedly listen to and trust these staff to apprise them of issues that might affect EBI provision. There appears to be alignment in leadership across staffing levels to support EBI implementation. |

|

Partially- Sustaining |

Outer Context: The CBO manager interacts with individual “champions” at the system-level (e.g., government officials) who want to introduce the EBI locally. Inner Context: See entry for fully-sustaining system. |

Outer Context: While the CBO manager continues to interact with system-level stakeholders, government officials/funders are reportedly reticent to “fix” problem areas, such as communication gaps between the system level and frontline staff. Inner Context: The CBO manager expresses a willingness to initiate organizational changes to support EBI implementation (e.g., ensuring that appropriate staffing, caseloads, and documentation is in place). |

Outer Context: Support gaps not attended to previously undermine implementation. Failure to institute strong networks with referral agents at the system-level presents challenges. However, like her/his peers in fully-sustaining systems, the CBO manager engages in outreach to referral agencies and other system stakeholders. Inner Context: The CBO manager establishes minimal infrastructure for the EBI in the CBO. S/he receives complaints from CBO staff about small caseloads. |

Outer Context: There is a dearth of champions for the EBI at the system-level. Government officials reportedly do little to address implementation issues, i.e., lingering problems with referrals. The CBO manager shoulders the burden of finding funding and clients to support ongoing use of the EBI. The manager wants to serve more clients and is set up to receive more referrals. Rather than support changes to the referral process, government officials cut funding for the EBI. Inner Context: The CBO manager expresses the desire for the organization to continue the EBI, but is apprehensive about the degree to which other system stakeholders (e.g., government officials and funders) will support ongoing implementation. |

|

Non- Sustaining |

Outer Context: The CBO managers appear to be largely uninvolved at the system-level until invited by system stakeholders (e.g., government officials and funder) to participate in implementation of the EBI. Inner Context: The CBO managers do not accord value to the EBI over care as usual. The managers do not appear to be on the cusp of pursuing cutting-edge services, as in the fully- and partially-sustaining systems. |

Outer Context: System-level stakeholders engage in few efforts to prepare existing infrastructure for the new EBI. They do not adapt or reduce redundancy in documentation to support CBO staff in implementing the EBI. They also experience problems in determining how best to reimburse for provision of the EBI. Communication between CBO managers and other system-level stakeholders is lacking. Inner Context: The CBO staff are trained but EBI implementation is delayed when unforeseen administrative and infrastructural problems (e.g., inconsistent reimbursement processes, problems with caseload management and referrals) arise. |

Outer Context: There is system- level turnover among government officials, and with the EBI frontline leader, resulting in loss of confidence among those who remain in maintaining the EBI. Efforts to implement stop-gap solutions for infrastructural limitations (e.g. attempting to bill for EBI provision with funding streams administered outside of child welfare services) are largely unsuccessful. System-level stakeholders eventually withdraw initial support for the EBI. Inner Context: The CBO managers experience trouble staffing the EBI and are unable to retain a key EBI frontline leader on staff. They suggest that CBO staff resist implementing the EBI, arguing that it is not suited to the local service delivery context or clientele. The staff are also reportedly skeptical of EBIs in general. |

Outer Context: N/A Inner Context: N/A. |

Policy and ideological trends

In fully sustaining systems, CBO managers were confident about the ability of their organizations to implement the EBI effectively and with fidelity and were taking steps to ensure sustainment. Yet many voiced concerns about system-level challenges outside their control and that of their local government partners, which could jeopardize future provision of the EBI. For example, managers in multiple systems worried about the effects of legislation on state and federal funding levels and priorities. One manager in a sustaining system observed that the EBI exemplified a progressive program for unsympathetic politicians in a politically-conservative area, stating, “We’ll see how that works, culturally, in the long term.” In general, however, managers clarified that efforts to support EBI implementation at the CBOs were subject to political machinations, such as the transition from one gubernatorial administration to the next with different priorities for child welfare services.

For instance, managers in a sustaining system feared that use of market-driven contracting processes favored by a new gubernatorial administration would dislodge the EBI. One manager related this process to broader ideological trends at work, noting, “There is a lot of movement towards… even more privatization and… out of state companies. I kind of see it, at least currently, [as] our legislative atmosphere would make us more at-risk than less at-risk.” This person also described the CBOs being left to serve the highest risk clients, whereas some private service providers relied instead on a combination of cherry-picking clients and Medicaid reimbursements to serve the “lowest hanging fruit,” claiming that these providers engaged in unseemly practices, such as drop- ping by child care centers where they could “probably find an adjustment disorder or some diagnosis they can slap on that allows them to bill Medicaid.”

Funding instability was the most ubiquitous outer-context influence confronting CBO managers throughout T1 to T3. Managers in fully sustaining systems had started pursuing creative and diverse funding arrangements to buffer the EBI from outer-context changes in funding as early as T1. To this end, one manager collaborated with staff at another CBO “to look for additional funding sources to expand upon what we’re doing or emphasize a mutual need.” This was also the case in the partially sustaining system, where a manager described his or her efforts to leverage money from four separate contracts to maintain home visitation staff to deliver the EBI. Only one system that had sustained SafeCare had a reliable funding stream dedicated to the EBI, but CBO managers here widely acknowledged that policy makers could easily divert this stream to other services based on outer-context considerations over which they had little influence.

Leadership in systems and organizations

The CBO managers from fully sustaining systems repeatedly emphasized that visionary government leaders in the outer context enabled them to serve as more effective managers within their own organizations. Summing up a view shared by many, one manager described local government leaders in praiseworthy terms, calling them “cutting edge,” while claiming they “never leave the dust settled.” Similarly, in the partially sustaining system, a manager stated that implementation had been positively influenced by a government official who was “very invested” in SafeCare and “a major supporter” from the start. In all but one case, the Exploration phase that led to system-wide implementation of the EBI originated within the outer context, either because of government-led initiatives to improve services, or of government officials being exposed to the EBI in other service systems and then deciding to introduce it within their own. However, CBO managers nonetheless played an often significant, visionary role in bringing SafeCare to their systems. In fully sustaining systems, managers reportedly became involved in exploration initia- tives early on as part of the larger network of CBO leaders involved in vetting the EBI. These individuals championed the potential benefits that SafeCare could bring to their service systems to cultivate enthusiasm for it among their staff in the inner context. The EBI was commonly characterized as part of necessary innovation, with one manager stating, “If you’re not growing, you’re dying.”

Although government leaders championing innovation at the system level were valued, managers also commented that effective system-level leadership needed to respond to the inner-context needs of CBO staff, a topic discussed below. A few managers expressed concern that government leaders were out of touch with the realities of implementation, rendering them well intentioned but ineffective, and argued that lower-level CBO staff needed to take part in troubleshooting discussions. One manager shared:

People were more reticent about what needed to be said or what was going on and I think that if we had a regular meeting at the next level down discussing some of those things, [implementation] might have been more effective.

This manager stated that midlevel CBO staff were best positioned to remedy challenges, calling for greater consultation with these stakeholders during Preparation and early Implementation phases.

In nonsustaining systems, CBO directors had unfavorable views of the system-level leaders, with whom they reported having minimal engagement. In partially- and nonsustaining systems, CBO managers in the inner context were much less involved in visioning and exploring the EBI. In one such system, the CBO director commented on an official from the funding agency that introduced SafeCare during the Exploration phase, asserting that she or he “was very adamant and really wanted us to pursue it, so we decided that we would implement to the best of our ability.” This manager lamented that it fell upon the CBO to comply with the demands of the funding agency official. In the other nonsustaining system, the CBO director felt that, despite government officials’ insistence on SafeCare, the program was a bad fit for their organization’s clientele, who had more urgent needs for food and housing. Longer-term support for the EBI among government officials was also reportedly variable. One manager described her or his local government officials’ support in general as “patchy” and attributed the EBI support that had once existed to a single champion at the government agency who had since left.

By contrast, though managers in some sustaining systems described similar challenges, they reportedly bridged the gap between outer-context leadership and inner-context needs by regularly communicating with government officials and fellow CBO managers during presentations and through interactions at county- or state-wide committees and councils. It was reportedly common for the CBO managers and government officials involved in the EBI to know each other from various other committees, coalitions, workshops, and panels, in which many served as chairpersons and board members. Managers described these types of interactions and involvements in relation to their interest in making their CBOs’ services known to the greater community and advocating for child welfare as stewards. Illustrating this point, one manager commented on holding multiple leadership roles:

I’ll be helping to some degree with the outreach, although my staff also does that, trying to promote [the EBI]. I see that as one of my jobs, because… it is part of my role to be in the community.

Another manager described sitting on a committee with government and funding agency stake- holders to design a strategic plan for child welfare services in their region, affirming that, “Everyone collaborates.”

Public–private partnerships

As these results indicate, successful EBI implementation reportedly necessitated partnerships between outer-context stakeholders, including officials from government agencies and public and private funding organizations, and CBO personnel in the inner context. In the Exploration phase, such partnerships helped generate an enduring buy-in among stakeholders across tiers comprising networked systems. Echoing the sentiments of others, one manager commented, “Everybody I’ve interacted with from the county level, and from the other agencies, are all very strongly in favor of what [the EBI] has accomplished, so it definitely has gotten me on the bandwagon.” Partnerships also contributed planning and problem-solving expertise for successful implementation. A manager in what became a fully sustaining system recalled the variety of stakeholders in a meeting about funding for the EBI, “I had the head of [a private funding organization] at the table, I had the head of the [government agency] at the table, [an academic collaborator] came with me, [another CBO manager] and myself.” Together, the stakeholders planned how initial training and roll out of the EBI would be subsidized through a private foundation, with the government agency assuming responsibility for financing implementation. Managers reported that such partnerships were important to the introduction of the EBI in T1, effective implementation in T2, and sustainment in T3. When asked about factors affecting the ability to implement the EBI over time, one manager emphasized “the support we have received from [government agency] and the other partners.”

In addition, managers commonly described a shared vision and consistent communication across inner- and outer-context stakeholders as necessary for building partnerships into stable networks for implementation. They also described how partnerships could be jeopardized by perceptions of mis- aligned goals or strategies, power struggles, or gaps in communication between the government officials, CBO managers, and staff responsible for delivering the EBI. These issues contributed to either partial or nonsustainment in three service systems. A manager from a nonsustaining system suggested that she or he had been willing to continue SafeCare, but that “nobody [at the government agency] picked up the ball and ran with it to continue it or to continue to have the conversation.” Similarly, a manager from the partially sustaining system described a situation in which government officials were unwilling to work with him or her to increase low EBI referrals and instead cut financing for the CBO contract by half. This individual felt that though implementation began as a collaboration between CBO staff and government officials, the responsibility to sustain the EBI fell on the CBO alone.

In fully sustaining systems, struggles were overcome through past histories and deliberate efforts to cultivate stable and cooperative networks of CBOs, supported by contracts that appeared to be predicated on a high degree of trust between principals and agents and awareness of each party’s needs related to EBI implementation. Much of this trust and awareness derived from the prior working relationships that led some CBOs to be singled out for future partnerships by local government officials. A group of CBO managers in a sustaining system agreed they had a “strong relationship with the county” and said their “application process wasn’t competitive,” but rather that the county had picked them for the EBI contract.

Procurement and contracting

As these comments indicate, an important aspect of successful inner- and outer-context partnerships in fully sustaining systems was establishing clearly written contracts explicating the necessary staff, referral procedures, and administrative processes (e.g., billing and reporting) to facilitate successful implementation of the EBI in the inner context, while also allowing room for negotiation and compromise. In these systems, CBO managers worked with system-level administrators to establish workable contracts prior to implementation that could be relied on for renewal into the future. Resulting contracts functioned as de facto policies guiding EBI implementation. In partially- and nonsustaining systems, elements of such a contract were missing or minimally established after implementation of the EBI had begun. A manager from the nonsustaining system complained, “The cart was placed in front of the horse in our county… We trained our staff and clinicians first and the bureaucracy and support systems for implementation came after.” In some fully- and partially sustaining systems, managers reportedly had to draw on organizational resources to subsidize or search for additional revenue streams when contracts did not fully cover the costs of EBI implementation. However, even in fully sustaining systems, procurement could present challenges to sustainment and undermine network stability due to structural changes in government financing unrelated to the EBI. As indicated earlier, CBO managers in one such system perceived a new procurement process as a threat to their existing government contracts. They suggested that the new process, which they had no input into developing, disrupted their trusting relationships with government officials. The process was also time-consuming to undertake, leading to delays in contract finalization, and creating worry for CBO staff. A manager in this system commented, I do think we’ll remain concerned in the future, if they continue to do this [procurement] process, that it could result in a very negative outcome in terms of who they choose [to contract with]. Someone [could come] in and … go through the [procurement] stages… but not really be capable of providing the service. I think that could happen very easily.

Managers observed that the new procurement process resulted in job insecurity among inner- context staff. “Staff are becoming increasingly concerned: ‘How come we don’t have any contracts, are our jobs okay?’ There’s a lot of anxiety at all levels.” Another manager agreed, “I believe it [the new procurement process] impacted our turnover. I can’t really have a measurement for morale but I know people were becoming less and less certain about the future and looking at other opportu- nities.” A third manager commented, “I think we did lose staff.”

Collaboration and co-opetition between CBOs

In the inner context, CBO managers in fully sustaining systems commonly reported strong, long- term relationships with peers at other CBOs. In these systems, managers had histories of sharing contracts and funding opportunities and consulting with and advising one another. They described such relationships as vital to organizational operations in service contexts where other resources were lacking. For example, some EBI-specific resources, such as certified trainers and coaches, were shared across CBOs.

Although elements of competition existed (e.g., tensions over subcontracting terms, negotiations over EBI training capacity), none of the systems reportedly had enough CBOs to make up a truly competitive marketplace. One CBO manager observed that out-of-state companies represented the biggest threat because staff from their own organizations knew and respected each other’s expertise and were less likely to foment competitive contests:

We have a reputation of having done this [EBI provision] very well for a very long time, and so when I look at … another type of bidding process, in which somebody seems to be doing something really well in our community, I don’t bid against them just because I want it. There’s that kind of respect for our projects, particularly in [this locality], that we’re not going to have local bidders if we actually are doing a good job.

Another CBO director remarked, “We’re all friends… We don’t like it when we have to go head-to- head like that. It happens, it is business, but we prefer to work otherwise.”

Competition between CBOs primarily occurred when intentionally introduced at the system level. In one system, CBO managers in the network were required to bid for contracts separately, despite their preference to work together. In another system, a government-supported study to examine uptake of the EBI demanded that CBO directors consent to randomization in an experimental or control condition. This led to a more competitive and adversarial environment between CBO staff that were chosen to implement the EBI and those that were to implement services as usual. Illustrating the point, a CBO manager involved in the study commented:

Most of us have been here from the beginning, so we got to where we call each other when we’re having problems or misunderstandings about, “Is this how we’re supposed to do it?” or “How are you all handling it?” Now I’m doing a different model, so we don’t get to.

Support for CBO staff

Managers in the fully sustaining systems were less likely to vacate their positions while they keenly championed the home visitation EBI to their staff, working closely with them to monitor implementation and respond to on-the-ground challenges throughout T1 to T3. In each EPIS phase, managers of CBOs in which the EBI had been sustained remained focused on creating a supportive organizational structure within the inner context that facilitated training and certification for coaches and home visitors, conveyed expectations and chains of command, and spread knowledge about the EBI among all staff (not just those implementing the EBI) to cultivate a “holistic view” and “continuity of treatment and support” for families, and to ensure broader organizational support. Although some expressed concern with the length of time it took to make the EBI viable within their respective service systems, they all attended meetings in which staff participated, talked up the EBI, and proactively responded to concerns raised by supervisors, home visitors, and other organizational employees.

Pragmatically, managers in the sustaining systems initiated multiple changes within their organizations to build this support, and to align leadership across staffing levels to support EBI implementation. These changes were typically instituted after challenges were encountered in the early Implementation phase—challenges that they learned about during their meetings and conversations with staff, when they asked staff about their experiences with the EBI and then developed troubleshooting strategies. The most pervasive solutions focused on garnering referrals from government agencies. This generally entailed educating child welfare stakeholders about the EBI and the types of cases that met intervention criteria, developing outreach materials (e.g., brochures), and streamlining referral forms. Several managers also advocated for greater government support for training and coaching expertise, which in four separate instances made the hiring of in-house coaches possible, thus reducing their organizations’ dependency on other CBOs for this type of implementation support. Major changes to the workflow of home visitors also occurred with case- loads decreased to accommodate the time needed for quality implementation.

Frontline staff also benefited from opportunities to move into midlevel trainer/coach, program management/coordination, and supervisory roles, through which they attended to the day-to-day dynamics of implementation. Over time, most managers became more strategic in terms of hiring decisions, purposefully screening job candidates for their openness to and prior experience with EBIs, increasing staff wages, providing greater administrative support, and subsidizing the costs of EBI supplies not covered by contracts. Several managers commented on how these measures enhanced staff perceptions that they were supported, while also enabling them to practice the EBI with fidelity and to achieve better outcomes for children and families.

In partially- and nonsustaining systems, the managers admittedly struggled or were reluctant to take the time to fully prepare or to integrate the EBI into service portfolios or the culture of their CBOs, characterizing the EBI as overly rigid, paperwork intensive, or unlikely to meet the needs of the local clienteles. They and their staff often shared the same criticism of the EBI, arguing that it did not constitute a good fit for their clients, whom they characterized as suffering from acute problems in living requiring intensive social service interventions. A manager in one such system explained:

I work with such a high-risk population that [it] wasn’t a good match for me, and I was actually the one that did approach the department to say that we needed to pull out because it wasn’t working with the families that we were working with at the time, that had multiple needs to address.

Emblematic of statements by peers in similar systems, she or he reiterated that SafeCare “just really wasn’t a good match for the clients” to rationalize its discontinuation. This line of reasoning was commonly articulated in T2 and T3 interviews among managers in nonsustaining systems who appeared less prone to leveraging their roles as leaders to accommodate delivery of the EBI for either individual providers or their CBOs.

Discussion

This study adds to the limited but growing literature on sustainment of human service EBIs (Aarons et al., 2011; Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, & Kyriakidou, 2004; Raffel et al., 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2018; Stirman et al., 2012) by focusing on the perspectives of CBO managers responsible for delivering child welfare services. Managers in this study held roles that placed them in frequent contact with system-level stakeholders (i.e., public officials, other leaders within the broader service- system network) and internal organizational players (i.e., frontline EBI delivery staff, coaches, and supervisors, other CBO managers). Our findings reveal differences in the behaviors, attitudes, and experiences of managers depending on their systems’ (and hence organizations’) sustainment status of the parenting EBI SafeCare.

In this study, successful sustainment of the EBI correlated with the early involvement of CBO managers in working with government officials in the Exploration and Preparation phases and fostering buy-in for the EBI among inner-context staff. Although CBO managers in sustaining systems described looking out for innovative collaboration opportunities with government stake- holders, funders, and other CBO leaders, managers in nonsustaining systems had reportedly agreed to implement the EBI as a result of institutional pressure and were primarily concerned with maintaining organizational stability and “business as usual” (McCarthy & Kerman, 2010). In addition, though CBO managers in sustaining systems emphasized the importance of developing strong staff support and cultivating an organization-wide belief in the value of the EBI, managers in partially- and nonsustaining systems emphasized a negative perception among their staff that the EBI was not well suited for their clients. Although the capacity to serve the targeted population with an EBI is a known variable affecting sustainment outcomes (Proctor et al., 2007; Raffel et al., 2013), it is possible that insufficient staff support and buy-in diminished the ability of partially- and nonsustaining CBOs to adapt the EBI to clientele needs.

The human service sector, and specifically child welfare, has been found to lack sufficient leadership development in relation to external realities of government devolution, increased competition for resources, and general organizational changes (Aarons, Ehrhart, Farahnak, & Sklar, 2014; Bernotavicz, McDaniel, Brittain, & Dickinson, 2013; Gifford, Davies, Edwards, & Graham, 2006; Gifford, Graham, Ehrhart, & Aarons, 2017; Richter et al., 2016). In this study, however, respected visionary leaders at the system level who were accessible to CBO managers (particularly government officials in high-level positions) were cited as sources of support, facilitating an innovative environment in which the managers were eager to participate. Per institutional theory, adoption in fully sustaining systems was encouraged by the direction of visionary leaders to pursue child welfare EBIs, and contract and funding structures designating SafeCare. These institutional forces provided the impetus for and helped ensure the success of implementation (Aldrich & Ruef, 2006; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Scott, 1992).

However, CBO managers in sustaining systems did not passively acquiesce to institutional pressure but described having high levels of proactive engagement with system-level stakeholders and forging strong relationships with county- and state-level decision makers as well as their peers at other CBOs during the Exploration phase. They reportedly used these relationships from the outset to negotiate detailed contracts, influence decision makers to overcome challenges, and build collaborative partnerships with other CBOs to share resources and ideas. The CBO managers thus responded strategically to institutional processes by engaging directly with institutional stakeholders to thereby exert their own influence and support the internal interests of their respective organizations (Oliver, 1991). In the Oliver (1991) typology of strategic responses to institutional processes, the actions of fully sustaining CBO managers can be characterized as “compromise,” exemplified by the tactic of balancing the interests of their organizations with the competing demands of multiple stakeholders over time. At the same time, these managers also utilized the tactic that Oliver calls “influence,” as they took the opportunity of partnerships with outer-context stakeholders during the Preparation and early Implementation phases to carry out strategic changes, including revised hiring guidelines and case assignment procedures, reduced caseloads, and incorporation of new personnel (e.g., EBI trainers/coaches and program managers/coordinators), and development of outreach materials that would support EBI implementation across the latter EPIS phases. These individuals thus acted strategically as “key change agents” for implementing new practices (Proctor et al., 2007). In contrast, though CBO managers in nonsustaining systems experienced notable pressure from policy makers to implement SafeCare, they pointed to insufficient institutional support and struc- tures (e.g., a contract to secure funding and provide guidance in addressing unexpected problems and costs) as reasons SafeCare was not maintained. Moreover, these managers felt that SafeCare did not align with their own professional values and norms or those of their staff and was unable to meet the immediate needs of their clienteles. For these reasons, CBO managers in nonsustaining systems responded by taking little initiative to forge strong relationships related to SafeCare with system-level stakeholders during the Exploration phase. This may be likened to the strategic response that Oliver (1991) calls “dismissing,” where institutional pressures may conflict with organizational objectives or norms, and the risk to CBOs of nonconformity is perceived to be low. As a result, CBO managers may have ignored early opportunities to develop buy-in and negotiate detailed contracts that support successful implementation and sustainment in favor of maintaining organizational norms and practices that they valued more highly.

Managers widely characterized relationships based on collaboration, partnership, and cooperation as vital to implementation and sustainment of the EBI. Establishing clear contract procedures and working together to support the implementation was linked to sustainment, whereas in a nonsustaining system, managers admittedly had not established a sufficient support system at either inner- or outer-context levels prior to implementation. Bunger (2013) found that otherwise competitive leaders of nonprofit human service agencies who perceive one another to be trustworthy may enter shared administrative coordination for mutual benefit. The more trustworthiness perceived, the more likely the partners are to sustain the relationship, as trust moderates the influence of competition and facilitates cooperation in risky environments. In this study, for example, implementation of SafeCare in one fully sustaining system relied heavily on long-term relationships already established between CBO managers in the child welfare sector. Even when competition and risk were introduced to the system by outer-context stakeholders, the managers shared information and support to ensure mutual success. This finding keeps with resource dependency theory, which suggests that CBO managers may be likely to enter into and maintain these types of relationships to acquire resources contributing to the fiscal health of their organizations despite the potential for reduced autonomy that relying on other organizations entails (Birken et al., 2017). However, as Oliver (1997) predicts, the collaborating managers were willing to accept reduced autonomy because of an existing norm of trust and cooperation that characterized the relationships of their organizations prior to EBI implementation.

In fact, though contractual relationships were hierarchically organized in fully sustaining systems, they were less reflective of traditional principal–agent arrangements that assume goal conflict and opportunistic/self-seeking behavior from CBO managers (Van Slyke, 2007). Managers in this study portrayed themselves and local government officials as stewards, working together to nurture service delivery infrastructures in which all stakeholders (including frontline staff) supported SafeCare over the long term. Managers in these systems often played active roles in selecting this EBI at the system level and then nurturing its integration within the workplace (Raffel et al., 2013). They also expressed the view that shared vision among system stakeholders facilitated goal alignment and development of organizational capacity to implement the EBI and contributed to overall network stability. This, in turn, made sustainment of the EBI possible, even during significant leadership changes in one service system.

Several CBO managers claimed funding for the EBI was inadequate, forcing CBOs to subsidize aspects of service provision. Funding plays a pivotal role in whether and how human service EBIs are implemented and sustained (Raffel et al., 2013). Not surprisingly, though managers in this study generally counted on renewal of their contracts, they recognized that outer-context changes in procurement and financing practices could imperil the EBI and the CBOs. Thus, managers in fully sustaining systems were actively engaged in efforts to investigate and secure funding streams to ensure continuation of the EBI, with planning occurring throughout the EPIS phases (Aarons, Ehrhart, & Farahnak, 2014; Aarons et al., 2016). Having the ability to collaborate with other CBOs was a commonly cited reason why systems could sustain SafeCare amid funding shifts. Here, managers attempted to mitigate their dependency on traditional public funding streams, though as described above, they often did so via forming new relationships of dependency with other organizations. The CBO managers in the partially- and nonsustaining systems thus tended to be more invested in their organizations’ well-being, rather than moving in the same direction as the larger service system. They also encountered problems emanating from the outer context relating to insufficient support or responsiveness regarding matters that were likely to affect the success of the EBI. These problems may have been symptomatic of low network stability or of possible breakdowns in the existing network. Our future research will focus on how such networks are formed and how they shift over time to better understand their implications for child welfare EBI provision in public- sector systems.

This study underscores the pivotal role that CBO managers in child welfare organizations can play in implementation efforts through collaboration at the system level, promoting buy-in for an EBI among key stakeholders (e.g., frontline providers), and fostering an inner-context environment conducive to uptake and sustainment of EBIs (Aarons et al., 2014; Aarons & Sommerfeld, 2012). The CBO managers in the systems sustaining the EBI demonstrated specific characteristics that likely contributed to system support and continued use of the practice, including the capacity for shared vision, goal alignment, and effective communication. Nonetheless, it may be unreasonable to assume that those in leadership and management roles will naturally have or develop the knowledge, skills, abilities, and behaviors to nurture a positive climate for EBI implementation and sustainment on their own. There may be a need for leader development interventions centered on these issues that are evidence based and relevant for managers of child welfare CBOs, such as the Leadership and Organizational Change for Implementation (LOCI; pronounced lō-sī; Aarons, Ehrhart, Farahnak, & Hurlburt, 2015), Implementation Leadership (iLEAD; Richter et al., 2016), and the Ottawa Model of Implementation Leadership (O-MILe: Gifford et al., 2006, 2017).

Limitations

This qualitative work occurred in two states experienced with one child welfare EBI and concentrated on the perspectives of a single stakeholder group. The study sample also featured a preponderance of White participants, nearly one half of whom took part in more than one data collection activity across T1 to T3. These constraints limit generalizability. Because most sites achieved the goal of sustaining the EBI, the sample of partially- and nonsustaining systems was small. Thus, fewer data with which to examine implementation and sustainment issues in these settings were available. We also recognize that the CBO managers may have had vested interests in portraying themselves, their organizations, the systems in which they participate, and the home visitation EBI in a positive light. However, the descriptive results described here strongly complement and elaborate on those presented in our previous analyses of EBI implementation and sustainment in the service systems included in this study (Aarons, Fettes, et al., 2014; Green et al., 2016; Willging et al., 2015).

Conclusion

The views of CBOs managers help disentangle inner- and outer-context factors impinging on implementation of child welfare EBIs (Aarons et al., 2011; Palinkas & Aarons, 2009) and have practical application for human service organizations. Stakeholders in these organizations are situated at the confluence of system-level demands and frontline needs. They must respond strategically to institutional pressures to ensure the viability of their organizations and deliver services to a vulnerable population. Implementation research on how and why CBO managers respond to different kinds of institutional processes and relationships may shed light on how we can foster child welfare systems conducive to EBIs (Willging et al., 2016).

We encourage government officials/funders and implementation science researchers interested in large-scale uptake and sustainment of human service EBIs to recognize that CBOs are not interchangeable contractors operating independently in an open marketplace. This study instead points to the need for government officials/funders to constructively support CBOs to advance necessary intraorganizational changes and nurture midlevel and frontline staff involved in EBI provision, efforts that are likely to contribute to network stability. Consideration of key factors in the EPIS can inform such efforts. Our research also suggests that trust and cooperation among CBO managers and system stakeholders, and robust, strategic leadership at the system level may broadly promote shared vision, goal alignment, and resource investment in child welfare EBIs. This support was demonstrated in the sustaining systems through collaborative efforts among CBO managers and government officials/funders to develop and instantiate training and coaching capacity locally. Yet, however involved they may be in such networks and the collaborations that shape them, the CBO managers in this study emphasized the vulnerability of the network in general, and their organizations specifically, to outer-context changes that they cannot control. This vulnerability, in turn, can impact the inner context of service delivery and undermine EBI sustainment. Interventions that focus on building effective leadership in human service CBOs may nurture both knowledge and skills for addressing such challenges as they arise, while enabling an inner context that is supportive of EBI implementation and sustainment.

Practice points.

Successful implementation of interventions involved early and sustained involvement of organizational managers in fostering buy-in among staff, forging relationships with system-level decision-makers and peers at other agencies, and fostering an organizational environment conducive to implementing the intervention.

Characteristics of successful managers included the capacity for shared vision, goal alignment, and effective communication.

Policy makers and managers of human service agencies should consider nurturing effective leadership via evidence-based leader development interventions.

Funding

This study is supported by U.S. National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH072961 and R01MH092950 and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant R01CE001556 (Principal Investigator: Gregory A. Aarons). We thank our participants for their collaboration and involvement in this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, & Farahnak LR (2014). The implementation leadership scale (ILS): Development of a brief measure of unit level implementation leadership. Implementation Science, 9, 45 10.1186/1748-5908-9-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, & Hurlburt MS (2015). Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): A randomized mixed method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation. Implemention Science, 10, 11 10.1186/s13012-014-0192-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, & Sklar M (2014). Aligning leadership across systems and organiza tions to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 255–274. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Fettes DL, Hurlburt MS, Palinkas LA, Gunderson L, Willging CE, & Chaffin MJ (2014). Collaboration, negotiation, and coalescence for interagency-collaborative teams to scale-up evidence-based practice. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43(6), 915–928. 10.1080/15374416.2013.876642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Green AE, Trott E, Willging CE, Torres EM, Ehrhart MG, & Roesch SC (2016). The roles of system and organizational leadership in system-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: A mixed-method study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 991–1008. 10.1007/s10488-016-0751-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, & Sommerfeld DH (2012). Leadership, innovation climate, and attitudes toward evidence-based practice during a statewide implementation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51 (4), 423–431. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich HE (1979). Organizations and environments Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich HE, & Ruef M (2006). Organizations evolving (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press. [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhanyan AA, Kim HJ, & Lambright KT (2012). Closer than “Arms Length”: Understanding the factors associated with collaborative contracting. The American Review of Public Administration, 42(3), 341–366. 10.1177/0275074011402319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernotavicz F, McDaniel NC, Brittain C, & Dickinson NS (2013). Leadership in a changing environment: A leadership model for child welfare. Administration in Social Work, 37(4), 401–417. 10.1080/03643107.2012.724362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birken SA, Bunger AC, Powell BJ, Turner K, Clary AS, Klaman SL, … Weiner BJ(2017). Organizational theory for dissemination and implementation research. Implementation Science, 12, 62 10.1186/s13012-017-0592-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birken SA, DiMartino LD, Kirk MA, Lee SY, McClelland M, & Albert NM (2016). Elaborating on theory with middle managers’ experience implementing healthcare innovations in practice. Implementation Science, 11, 2 10.1186/s13012-015-0362-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birken SA, Lee SY, & Weiner BJ (2012). Uncovering middle managers’ role in healthcare innovation implementation. Implementation Science, 7, 28 10.1186/1748-5908-7-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunger AC (2013). Administrative coordination in non-profit human service delivery networks: The role of competition and trust. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(6), 1155–1175. 10.1177/0899764012451369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunger AC, Collins-Camargo C, McBeath B, Chuang E, Perez-Jolles M, & Wells R (2014). Collaboration, competition, and co-opetition: Interorganizational dynamics between private child welfare agencies and child serving sectors. Children and Youth Services Review, 38, 113–122. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Bard D, Bigfoot DS, & Maher EJ (2012). Is a structured, manualized, evidence-based treatment protocol culturally competent and equivalently effective among American Indian parents in child welfare? Child Maltreatment, 17(3), 242–252. 10.1177/1077559512457239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BR, Bumbarger BK, & Moore JE (2015). Sustaining evidence-based prevention programs: Correlates in a large-scale dissemination initiative. Prevention Science, 16(1), 145–157. 10.1007/s11121-013-0427-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, & Strauss A (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(50). 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demby H, Gregory A, Broussard M, Dickherber J, Atkins S, & Jenner LW (2014). Implementation lessons: The importance of assessing organizational “fit” and external factors when implementing evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(3 Suppl), S37–S44. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despard MR (2016). Challenges in implementing evidence-based practices and programs in nonprofit human service organizations. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 13(6), 505–522. 10.1080/23761407.2015.1086719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio PJ, & Powell WW (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. 10.2307/2095101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour S, Lessard D, & Chamberland C (2014). Facilitators and barriers to implementation of the AIDES initiative, a social innovation for participative assessment of children in need and for coordination of services. Evaluation & Program Planning, 47, 64–70. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershater-Molko RM, Lutzker JR, & Wesch D (2003). Project SAFECARE: Improving health, safety, and parenting skills in families reported for, and at-risk for child maltreatment. Journal of Family Violence, 18(6), 377–386. 10.1023/A:1026219920902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford W, Graham ID, Ehrhart MG, & Aarons GA (2017). Ottawa model of implementation leadership and implementation leadership scale: Mapping concepts for developing and evaluating theory-based leadership interventions. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 9, 15–23. 10.2147/JHL.S125558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford WA, Davies B, Edwards N, & Graham ID (2006). Leadership strategies to influence the use of clinical practice guidelines. Nursing Leadership, 19(4), 72–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Green AE, Trott E, Willging CE, Finn NK, Ehrhart MG, & Aarons GA (2016). The role of collaborations in sustaining an evidence-based intervention to reduce child neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 53, 4–16. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, & Kyriakidou O (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 581–629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EG, Padwa H, Fenwick K, Harris LM, & Aarons GA (2015). Identifying and ranking implicit leadership strategies to promote evidence-based practice implementation in addiction health services. Implementation Science, 11(1), 69 10.1186/s13012-016-0438-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]