Abstract.

Strongyloides stercoralis, a worldwide-distributed soil-transmitted helminth, causes chronic infection which may be life threatening. Limitations of diagnostic tests and nonspecificity of symptoms have hampered the estimation of the global morbidity due to strongyloidiasis. This work aimed at assessing S. stercoralis–associated morbidity through a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available literature. MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, LILACS, and trial registries (WHO portal) were searched. The study quality was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Odds ratios (ORs) of the association between symptoms and infection status and frequency of infection-associated symptoms were calculated. Six articles from five countries, including 6,014 individuals, were included in the meta-analysis—three were of low quality, one of high quality, and two of very high quality. Abdominal pain (OR 1.74 [CI 1.07–2.94]), diarrhea (OR 1.66 [CI 1.09–2.55]), and urticaria (OR 1.73 [CI 1.22–2.44]) were associated with infection. In 17 eligible studies, these symptoms were reported by a large proportion of the individuals with strongyloidiasis—abdominal pain by 53.1% individuals, diarrhea by 41.6%, and urticaria by 27.8%. After removing the low-quality studies, urticaria remained the only symptom significantly associated with S. stercoralis infection (OR 1.42 [CI 1.24–1.61]). Limitations of evidence included the low number and quality of studies. Our findings especially highlight the appalling knowledge gap about clinical manifestations of this common yet neglected soil-transmitted helminthiasis. Further studies focusing on morbidity and risk factors for dissemination and mortality due to strongyloidiasis are absolutely needed to quantify the burden of S. stercoralis infection and inform public health policies.

INTRODUCTION

Strongyloides stercoralis is a soil-transmitted helminth (STH) affecting 100–370 million people worldwide, mostly in tropical and subtropical regions.1 After penetration of the intact skin of the human host, the infective larvae (L3) migrate through the body tissues and molt. This acute phase of the infection is often completely asymptomatic or goes unnoticed. The adult female nematode settles in the intestine and produces eggs that hatch in the last part of the bowel, so that the first-stage larvae of the parasite (L1) and not the eggs are shed with feces. Some larvae molt to L3 before excretion and can reinfect the host by penetrating through the perianal skin or the rectal mucosa. This peculiar “autoinfective” cycle allows the perpetuation of the infection through the years, in the absence of further exposure to contaminated soil, contrary to what happens with the other STH infections.2 Thus, strongyloidiasis is a chronic infection, which may persist lifelong even in the absence of reinfection. Another peculiarity of S. stercoralis is its capacity to cause a life-threatening syndrome, as a result of accelerated parasite replication and larval dissemination to organs where migration usually does not occur. This condition occurs in individuals with certain types of immunosuppression, such as due to corticosteroid intake, but other risk factors for dissemination are still poorly known.2 Although the treatment with ivermectin is highly effective in the chronic phase of infection, it often fails in the case of hyperinfection/dissemination.3 Clinically, chronic infection with S. stercoralis presents with nonspecific symptoms involving the skin (itching and urticaria), the gastrointestinal tract (diarrhea and abdominal pain/distention), and the respiratory tract (asthma-like symptoms and dyspnea).2 However, the strength of the association between the infection status and these nonspecific symptoms commonly presented by infected individuals has been poorly defined. From the public health perspective, the issues related to this nonspecificity and uncertain association with infection of clinical symptoms, with the possible exception of larva currens,2 together with the inaccuracy of the diagnostic tests for strongyloidiasis,4,5 have had important consequences, such as 1) underestimation of the global prevalence of strongyloidiasis with previous estimates having been questioned only in recent years1 and 2) difficulty in evaluating the impact of the infection in terms of morbidity and mortality on populations living in endemic areas. As a result, the burden of strongyloidiasis is still unclear, and this has hampered the appraisal and implementation of specific control strategies in endemic areas. Indeed, S. stercoralis has not yet been included in the WHO programs for the control of STHs, despite the potentially fatal syndrome it may cause.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the morbidity due to S. stercoralis infection, through identification of symptoms associated with the infection status (primary outcome) and by estimating the proportion of infected people reporting those symptoms. This was conceived as a first step toward estimating the clinical burden caused by strongyloidiasis to support public health stakeholders in evaluating the need of implementing specific control programs. Although the burden of disease estimates should also be based on severe morbidity and mortality caused by the disseminated infection, it is extremely difficult to quantify these conditions because of the impossibility of performing prospective controlled trials without intervention on infected people and the difficulty in obtaining good quality data with other study designs.3 For this reason, severe morbidity and mortality were not addressed in the present review.

METHODS

Search strategy.

The protocol of the review was published in the PROSPERO international prospective registry of systematic reviews6 (registration no. CRD42018088225). The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, CENTRAL (Cochrane Library), and LILACS (Bireme). In addition, we searched trial registries via the WHO portal. The search was performed, in all the database sources, on October 31, 2017. Databases were searched using the keywords: “strongyloidiasis”, “Strongyloides stercoralis”, “soil transmitted helminths”, “anguillulose”, and “anguillulosis”. The detailed strategy is available in Supplemental Table 1. The search results were combined and duplicates removed before screening for relevance. The reference lists of all included studies were searched for other potentially relevant articles. No restriction was applied regarding language, publication date, or publication status. The work is presented according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.7

Population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, study design, and outcomes.

Original studies reporting symptoms presented by individuals, of all ages and both sexes, infected with S. stercoralis were included in this review. No restriction was applied regarding publication type (e.g., research article or conference report) or setting (endemic or non-endemic area and field or clinical setting). We included cross-sectional, case–control, and interventional studies. Cross-sectional and case–control studies, including a control group not infected with S. stercoralis, were used for the meta-analysis to evaluate the association of infection with symptoms; interventional studies were also included to determine the proportion of S. stercoralis–infected individuals with symptoms. Case reports and case series, as well as review articles, were excluded. Among studies with eligible design, those focusing on a subset of infected patients (e.g., patients with S. stercoralis larval counts above a designated threshold) were excluded. Only studies where S. stercoralis infection was diagnosed by Baermann method or stool culture were included; other copromicroscopic methods (e.g., direct fecal smear examination, Kato–Katz, and formol–ether concentration) and serology were excluded because of low sensitivity and specificity, respectively, which would have implied the misclassification of a high proportion of individuals. In the reviewed studies, self-reported symptoms were assessed by questionnaires.

Study selection and data extraction.

Two authors (F. T. and E. M.) reviewed titles and abstracts of publications identified by the search to identify all studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria. After having obtained the full text of the potentially eligible articles, the two authors independently assessed whether or not each study met the inclusion criteria using an eligibility form. Potentially eligible studies were excluded if 1) the full text and abstract were both unavailable or only the abstract was available but did not convey the needed data, 2) symptoms were not described, 3) symptoms were indicated but the needed data were not extractable, 4) symptoms were described for a subgroup of infected individuals only, 5) the diagnostic method was not mentioned or not eligible, 6) S. stercoralis was not investigated, and 7) the study was duplicated. When F. T. and E. M. did not reach a consensus, a third review team member (D. B.) made the final decision. Two authors (F. T. and S. S.) independently performed the data extraction using a predesigned data extraction form (Excel file). Any disagreement regarding the data extraction was resolved by discussion between the two authors. When necessary, a third author (D. B.) facilitated the discussion until a consensus was reached. The following data were extracted: 1) study design, 2) study methodology (diagnostic method and recall time frame of symptoms), 3) study population (number of individuals examined and setting [village-based or selected data set]), and 4) target symptoms (symptoms investigated and number of individuals reporting symptoms). Among reported symptoms, the following were included in our analysis, based on the results of self-reported symptoms extracted by eligible articles: gastrointestinal (specifically abdominal pain and diarrhea), respiratory (specifically cough), and dermatological (specifically diffuse itching and pruritic rash/urticaria), as reported in each study.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis.

Odds ratios (ORs) of the association between symptoms and infection status for each study were calculated, together with their corresponding 95% CI. The Mantel–Haenszel method with fixed effect and random effects models was then used to obtain a pooled estimate of the effect of each symptom. The and the DerSimonian–Laird estimator for were also calculated as measures of heterogeneity. Forest plots were used to illustrate the point estimate with 95% CI. The frequency of symptoms significantly associated with the infection was calculated as the proportion of the total number of infected individuals with each self-reported symptom over the total number of infected individuals in all eligible studies; for interventional studies, the number of infected individuals with symptoms pretreatment was extracted. The meta-analysis was performed using R version 3.4.3,8 package “meta,” command “metabin.” A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Quality assessment.

The quality of each study included in the meta-analysis was assessed using an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale,9 which consisted of three main domains: selection of studies, comparability, and outcome. Supplemental Table 2 summarizes the items included in each domain and the characteristics for the attribution of the “stars” (scoring system). Quality was assessed at study level and was expressed as low (in case a single or two stars were assigned to the study), high (three or four stars), or very high (five to six stars).

RESULTS

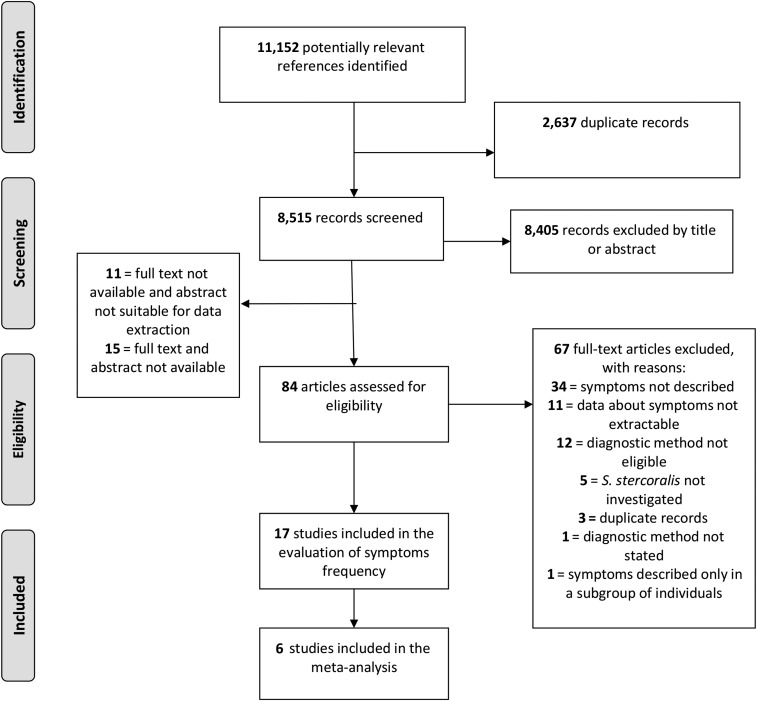

The search and selection of included studies is shown in Figure 1. The database search retrieved a total of 11,152 records. After duplicates were removed, 8,515 records were screened for potential eligibility by title and abstract, and 110 articles were selected for full text review. Of these, 93 were further excluded, leaving 17 articles for the evaluation of the frequency of S. stercoralis–associated symptoms in the infected population, and, among these, six10–15 were eligible for meta-analysis of the association between S. stercoralis infection and the selected symptoms (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for search and selection of included studies.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of included articles

| Study* | Design | Country | Age group | Diagnostic test | Ss infected individuals | Abdominal pain† | Diarrhea† | Cough | Itching | Urticaria† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forrer et al.11* | cs | Cambodia | All ages | Stool culture + Baerman | 853 | y | y | y | y | y |

| Khieu et al.13* | cs | Cambodia | All ages | Stool culture + Baerman | 601 | y | y | y | y | y |

| Suputtamongkol et al.25 | i | Thailand | Adults | Stool culture | 90 | y | y | n | n | n |

| Becker et al.10* | cc | Ivory Coast | All ages | Stool culture + Baerman | 37 | y | y | y | y | y |

| Herrera et al.12* | cc | Peru | All ages | Baermann | 50 | y | y | n | n | y |

| Marcos et al.19 | i | Peru | All ages | Baermann | 33 | n | n | n | n | y |

| Zaha et al.26 | i | Japan | Adults | Stool culture | 50 | y | y | n | y | y |

| Rodriguez Calabuig et al.15* | cc | Spain | Adults | Stool culture + Baerman | 47 | n | n | y | y | n |

| Cremades Romero et al.17 | i | Spain | Adults | Stool culture | 37 | n | y | y | y | y |

| Marti et al.20 | i | Tanzania | Children | Baermann | 333 | n | n | y | y | y |

| Shikiya et al.22 | i | Japan | Adults | Stool culture | 23 | n | y | n | n | n |

| Zaha et al.27 | i | Japan | Adults | Stool culture | 299 | y | y | n | y | y |

| Oyakawa et al.21 | i | Japan | Adults | Stool culture | 161 | y | y | n | y | y |

| Shikiya et al.24 | i | Japan | Adults | Stool culture | 54 | y | y | n | y | y |

| Shikiya et al.23 | i | Japan | Adults | Stool culture | 59 | y | y | n | y | y |

| Oliver et al.14* | cc | Tasmania | Adults | Stool culture | 18 | y | y | n | n | y |

| Grove18 | i | Australia | Adults | Stool culture | 42 | n | y | n | n | y |

cc = case–control; cs = cross-sectional; i = interventional; n = no-symptom not reported in the article; Ss = Strongyloides stercoralis; y = yes-symptom reported in the article.

* Included in the meta-analysis.

† Symptoms associated with Strongyloides stercoralis infection as assessed by meta-analysis.

Among described symptoms, gastrointestinal (specifically abdominal pain and diarrhea), respiratory (specifically cough), and dermatological (specifically diffuse itching and itching rash/urticarial) were consistently reported by three or more studies and were included in the meta-analysis. Other mentioned symptoms, such as asthma, loss of appetite/anorexia, tiredness, stunting, muscle pain, fever, constipation, and anemia, were not included.

Strongyloides stercoralis infection and association with gastrointestinal, respiratory, and cutaneous symptoms.

Six studies reported the frequency of at least one of the five target symptoms in S. stercoralis–infected individuals and uninfected controls. In particular, three studies reported the frequency of all target symptoms, two studies reported the frequency of three target symptoms, and one study reported only the frequency of two of the target symptoms (Table 1). Of the six studies included, three were considered to be of low quality, one of high quality, and two of very high quality (Supplemental Table 3). Heterogeneity among studies was high (I2 ranging from 67% to 85%); hence, the interpretation of these results should be based on the random effects model. However, we also present the results of the fixed effects models to provide a more complete picture of the summary effect.16

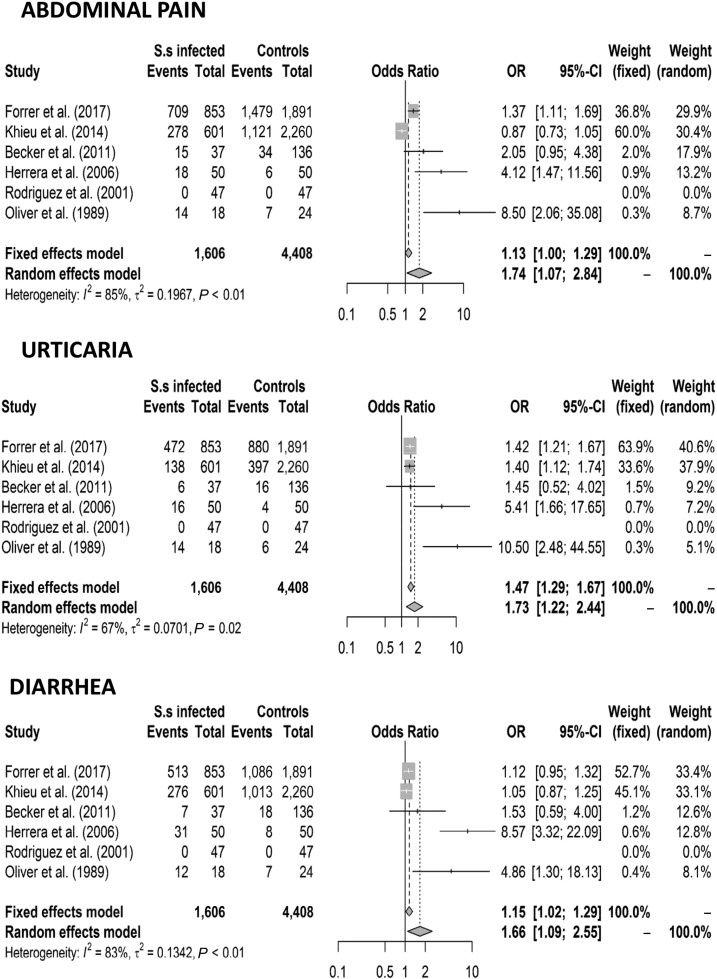

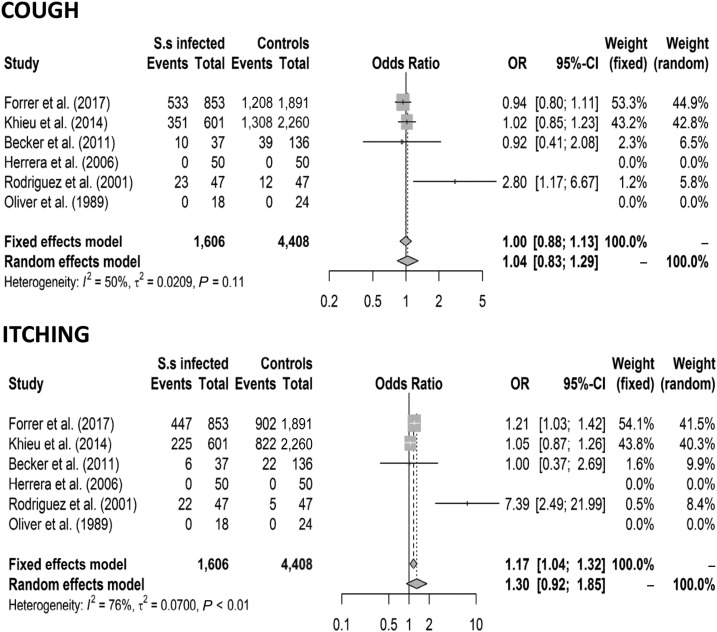

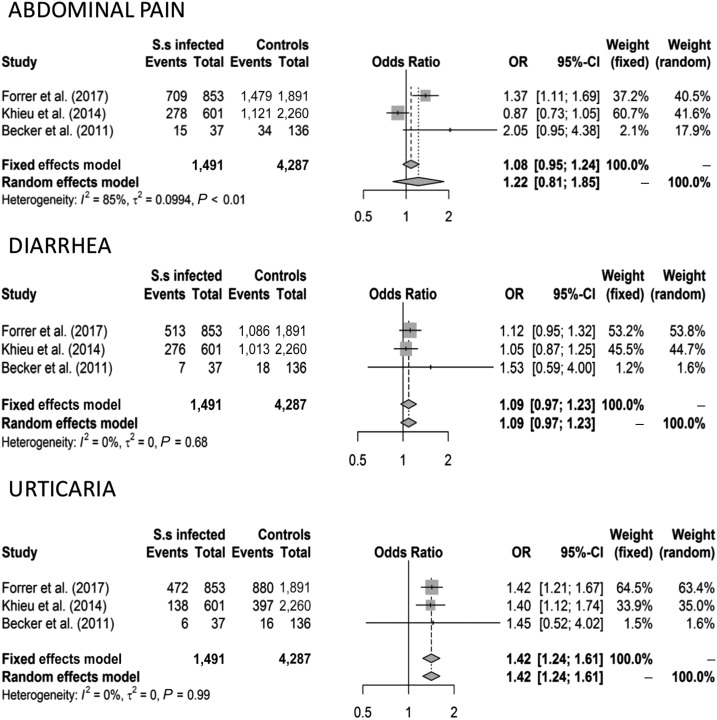

When all eligible studies were analyzed (including 1,606 patients and 4,408 controls), abdominal pain (OR 1.13 [CI 1.00–1.29] fixed effects model and OR 1.74 [CI 1.07–2.94] random effects model), diarrhea (OR 1.15 [CI 1.02–1.29] fixed effects model and OR 1.66 [CI 1.09–2.55] random effects model), and urticaria (OR 1.47 [CI 1.29–1.67] fixed effects model and 1.73 [CI 1.22–2.44] random effects model) were associated with S. stercoralis infection, whereas cough and itching were not. The results are shown in Figures 2 and 3. After removing the low-quality studies, the meta-analysis was repeated with a smaller number of individuals (1,491 patients and 4,287 controls); urticaria remained the only symptom significantly associated with S. stercoralis infection (OR 1.42 [CI 1.24–1.61] fixed and random effects models) (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Forest plots for the association between Strongyloides stercoralis infection and symptoms (abdominal pain, urticaria, and diarrhea).

Figure 3.

Forest plots for the association between Strongyloides stercoralis infection and symptoms (cough and itching).

Figure 4.

Forest plots for the association between Strongyloides stercoralis infection and symptoms after removal of the low-quality studies.

Of the included articles, only three reported coinfection with hookworms, two of which in a high percentage of S. stercoralis–infected people (38–47%),11,13 whereas this figure was not detailed in the third article.10

Frequency of S. stercoralis–associated symptoms in the infected population.

Seventeen studies10–15,17–27 presented the number of infected individuals who self-reported at least one of the five target symptoms (Table 1). When considering only studies reporting symptoms associated with S. stercoralis infection by meta-analysis, abdominal pain was reported by 1,206 individuals (53.08%) of 2,272 investigated by 11 studies, diarrhea by 987 individuals (41.57%) of 2,374 investigated by 14 studies, and urticaria/rash by 730 individuals (27.79%) of 2,627 investigated by 14 studies. Although we did not carry out a formal quality assessment of the studies used to evaluate the frequency of S. stercoralis–associated symptoms, it must be highlighted that in only three studies10,11,13 self-reported symptoms experienced in the 2–4 weeks were specifically investigated. In one case,25 symptoms were those reported at the time of therapy, and in all other cases, the recall time frame was not stated.

DISCUSSION

Strongyloides stercoralis infection is among the most neglected and elusive parasitic conditions worldwide. Our review attempted for the first time to explore rigorously the available published evidence of the morbidity due to this infection, to photograph the type of data available, and to assess completeness or knowledge gaps. We found the appalling result that there is a lack of studies exploring this condition. This, as is typically the case for neglected diseases, results in lack of evidence, which should not be interpreted as the absence of relevant morbidity due to chronic infection in the affected populations. Urticaria was the symptom with the strongest association with strongyloidiasis. This was confirmed when considering only studies of high quality. Diarrhea and abdominal pain had weaker associations with the parasitic infection, but this result was not confirmed when only studies with good quality scores were included in the meta-analysis. Cough and itching did not show any association with strongyloidiasis. These results were somehow surprising. Indeed, abdominal pain and diarrhea are commonly reported by infected people, as also confirmed by the results of our systematic review, which found that the proportion of infected individuals reporting these two symptoms was high. It also seems intuitively difficult to exclude itching from the symptoms characterizing affected individuals, when results demonstrated that urticaria is associated with strongyloidiasis.

In general, it should be taken into account that data collection with questionnaires might have been influenced by many factors, including the recall time for the symptoms (which can be intermittent and thus not present in the time frame considered) and the different meaning of the medical terminology used in the questionnaires compared with that meant by lay people. Therefore, these results cannot be considered conclusive and highlight the need for further, well-designed studies more accurately addressing the type and characteristics of symptoms generally considered as associated with strongyloidiasis.

It must also be stressed that, in our present work, it was not possible to evaluate other medically relevant symptoms that may affect infected individuals but that have been only recently addressed in studies focusing on strongyloidiasis (for instance, anemia28 and stunting in children11). Therefore, these should be evaluated in future work and included in the estimate of the clinical burden caused by strongyloidiasis, together with severe and fatal cases that are clearly underdiagnosed and underreported.3

Limitations.

Our work has several limitations. First, S. stercoralis has been receiving a relatively higher attention only in recent years, so we found few studies specifically concerning this parasite, and most of them were of low quality. The diagnostic methods used in these studies, although more sensitive than the widely used Kato–Katz, direct smear, and formol–ether concentration techniques, still miss a high proportion of infected people; hence, the control groups might have included many individuals misclassified as “uninfected.” Furthermore, symptoms associated with strongyloidiasis are not constantly present in all affected patients. These factors may contribute to an underestimation of the morbidity. Moreover, very few studies were eligible for the meta-analysis and were further reduced if stringent quality criteria were applied. The presence of coinfections causing similar symptoms is another confounding factor that could be partly overcome by statistical adjustments. However, information on coinfection was often missing or poorly detailed in the included articles, and hence, we could not further analyze this factor. Finally, the small number of studies did not allow the association and frequency of symptoms in subgroups of individuals, such as in children, to be evaluated.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our work highlights the appalling lack of studies addressing morbidity associated to chronic strongyloidiasis that makes it difficult to estimate the burden of infection, also in light of the known knowledge gap about the most severe disease manifestations, that is, disseminated strongyloidiasis and associated mortality. Considering that strongyloidiasis is a potentially fatal STH infection, the neglect of this parasitic infection is no longer justifiable, and high-quality studies focusing on this infection are much needed to inform public health policies.

Supplementary Files

Note: Supplemental tables appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bisoffi Z, et al. 2013. Strongyloides stercoralis: a plea for action. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nutman TB, 2017. Human infection with Strongyloides stercoralis and other related Strongyloides species. Parasitology 144: 263–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buonfrate D, Requena-Mendez A, Angheben A, Munoz J, Gobbi F, Van Den Ende J, Bisoffi Z, 2013. Severe strongyloidiasis: a systematic review of case reports. BMC Infect Dis 13: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buonfrate D, Requena-Mendez A, Angheben A, Cinquini M, Cruciani M, Fittipaldo A, Giorli G, Gobbi F, Piubelli C, Bisoffi Z, 2018. Accuracy of molecular biology techniques for the diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection—a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12: e0006229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Requena-Mendez A, Chiodini P, Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D, Gotuzzo E, Munoz J, 2013. The laboratory diagnosis and follow up of strongyloidiasis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination , 2018. Prospero International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. York, UK: University of York; Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero. Accessed June 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Equator Network Enhancing the Quality and Transparency Of Health Research. Available at: http://www.equator-network.org/?post_type=eq_guidelines&eq_guidelines_study_design=systematic-reviews-and-meta-analyses&eq_guidelines_clinical_specialty=0&eq_guidelines_report_section=0&s=+. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- 8.R Core Team , 2017. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed February 9, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aru RG, Chilcutt BM, Butt S, deShazo RD, 2017. Novel findings in HIV, immune reconstitution disease and Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Am J Med Sci 353: 593–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker SL, Sieto B, Silue KD, Adjossan L, Kone S, Hatz C, Kern WV, N’Goran EK, Utzinger J, 2011. Diagnosis, clinical features, and self-reported morbidity of Strongyloides stercoralis and hookworm infection in a co-endemic setting. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5: e1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrer A, Khieu V, Schar F, Hattendorf J, Marti H, Neumayr A, Char MC, Hatz C, Muth S, Odermatt P, 2017. Strongyloides stercoralis is associated with significant morbidity in rural Cambodia, including stunting in children. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0005685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrera J, Marcos L, Terashima A, Alvarez H, Samalvides F, Gotuzzo E, 2006. Factors associated with Strongyloides stercoralis infection in an endemic area in Peru [in Spanish]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru 26: 357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khieu V, Schar F, Marti H, Bless PJ, Char MC, Muth S, Odermatt P, 2014. Prevalence and risk factors of Strongyloides stercoralis in Takeo Province, Cambodia. Parasit Vectors 7: 221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliver NW, Rowbottom DJ, Sexton P, Goldsmid JM, Byard R, Tooth M, Thomson KS, 1989. Chronic strongyloidiasis in Tasmanian veterans–clinical diagnosis by the use of a screening index. Aust N Z J Med 19: 458–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez Calabuig D, Igual Adell R, Oltra Alcaraz C, Sanchez Sanchez P, Bustamante Balen M, Parra Godoy F, Nagore Enguidanos E, 2001. Agricultural occupation and strongyloidiasis. A case-control study [in Spanish]. Rev Clin Esp 201: 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Stephenson M, Aromataris E, 2015. Fixed or random effects meta-analysis? Common methodological issues in systematic reviews of effectiveness. Int J Evid Based Healthc 13: 196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cremades Romero MJ, Igual Adell R, Ricart Olmos C, Estelles Piera F, Pastor-Guzman A, Menendez Villanueva R, 1997. Infection by Strongyloides stercoralis in the county of Safor, Spain [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc) 109: 212–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grove DI, 1982. Treatment of strongyloidiasis with thiabendazole: an analysis of toxicity and effectiveness. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 76: 114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcos L, Terashima A, Samalvides F, Alvarez H, Lindo F, Tello R, Canales M, Demarini J, Gotuzzo E, 2005. Thiabendazole for the control of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a hyperendemic area in Peru [in Spanish]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru 25: 341–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marti H, Haji HJ, Savioli L, Chwaya HM, Mgeni AF, Ameir JS, Hatz C, 1996. A comparative trial of a single-dose ivermectin versus three days of albendazole for treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis and other soil-transmitted helminth infections in children. Am J Trop Med Hyg 55: 477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oyakawa T, et al. 1991. New trial with thiabendazole for treatment of human strongyloidiasis [in Japanese]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 65: 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shikiya K, Kinjo N, Uehara T, Uechi H, Ohshiro J, Arakaki T, Kinjo F, Saito A, Iju M, Kobari K, 1992. Efficacy of ivermectin against Strongyloides stercoralis in humans. Intern Med 31: 310–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shikiya K, Kuniyoshi T, Higashionna A, Arakkaki T, Oyakawa T, Kadena K, Kinjo F, Saito A, Asato R, 1990. Treatment of strongyloidiasis with mebendazole and its combination with thiabendazole [in Japanese]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 64: 1408–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shikiya K, Uehara T, Uechi H, Ohshiro J, Arakaki T, Oyakawa T, Sakugawa H, Kinjo F, Saito A, Asato R, 1991. Clinical study on ivermectin against Strongyloides stercoralis [in Japanese]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 65: 1085–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suputtamongkol Y, Premasathian N, Bhumimuang K, Waywa D, Nilganuwong S, Karuphong E, Anekthananon T, Wanachiwanawin D, Silpasakorn S, 2011. Efficacy and safety of single and double doses of ivermectin versus 7-day high dose albendazole for chronic strongyloidiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5: e1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaha O, Hirata T, Kinjo F, Saito A, Fukuhara H, 2002. Efficacy of ivermectin for chronic strongyloidiasis: two single doses given 2 weeks apart. J Infect Chemother 8: 94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaha O, et al. 1992. Clinical study on symptoms in patients with strongyloidiasis [in Japanese]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 66: 1378–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Echazu A, et al. 2017. Albendazole and ivermectin for the control of soil-transmitted helminths in an area with high prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis and hookworm in northwestern Argentina: a community-based pragmatic study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0006003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.