Letter to Editor:

We appreciate the letter by Zaman et al.16 in response to our recent article.11 The principal objective of our article11 was to evaluate whether psychological processes such as appraisal mediate the effects of temperature on autonomic responses, or whether autonomic arousal in response to noxious heat is purely reflexive, as proposed by the IASP definition7—a goal which we assert multiple times (eg, Introduction11). We feel that this question is more fundamental than the related, but secondary, question of directionality between pain and autonomic responses, on which Zaman et al.16 focus. The letter also highlights 2 important points that were discussed explicitly in our Discussion11: (1) caveats to correlational mediation and (2) the influence of psychological factors on pain and pain-evoked autonomic responses. Thus, although there are many points of agreement, Zaman et al. have unfortunately mischaracterized the central goal of our work.

We agree that mediation analysis is not sufficient to establish causality, as has been discussed extensively in statistics, experimental psychology, and related fields.4,8,9,13–15 In the dominant approach to mediation, researchers test the association of a manipulated or measured proposed causal variable with a putative effect variable and test whether a measured mediator variable statistically accounts for this association. Ideally, the mediator would then be experimentally manipulated to establish a causal mechanism.13 In our Discussion,11 we propose that future investigations use pharmacological interventions to modulate pain and test whether intensity effects on autonomic responses are abolished. This would supplement and extend our statistical mediation and indicate causality. A similar approach (ie, pharmacological modulation of pain vs sympathetic nervous system activity) could formally test the somatic marker hypothesis5 and questions of directionality between pain and autonomic responses raised by Zaman et al.16

When a mediator is measured and not manipulated, this approach is limited and can be prone to alternative explanations, as discussed by Zaman et al.16: (1) reversed or reciprocal relationships between the mediator and other variables in the mediation model8,9,14 and (2) confounding third variables that may account for correlations between variables in the mediation model.4,6,10 We agree with Zaman et al. that our research on the role of pain in heat effects on autonomic responses is limited in its ability to definitely reveal causal conclusions about pain as a mediator. This is why we extensively discussed limitations and offered experimental solutions in our Discussion.11

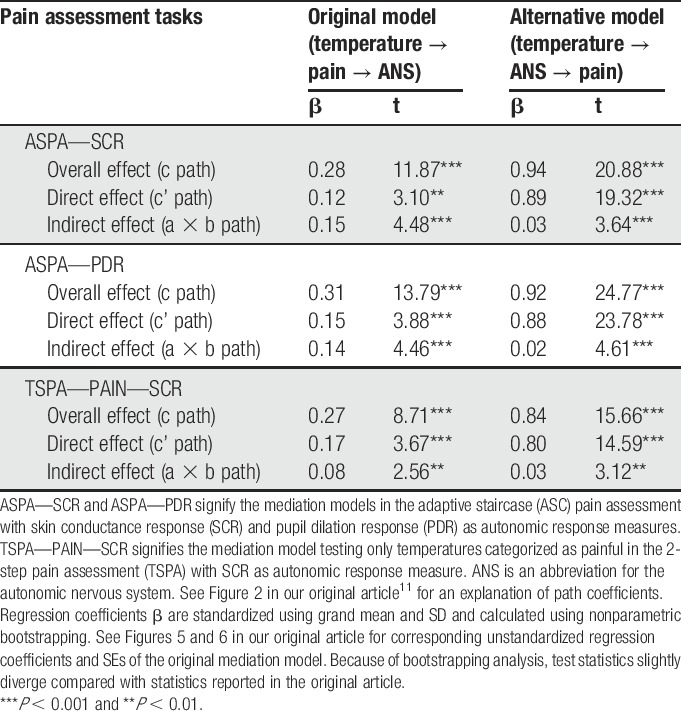

However, we disagree with Zaman et al.'s suggestion that we misuse the term “mediation.” Zaman et al. postulate that time precedence, ie, measuring the proposed mediator before the proposed dependent variable is a sine qua non condition for labeling a variable as mediator.8 Because we had to measure pain after the autonomic response, we supposedly violated this labeling standard. However, even time precedence in measuring the proposed cause (X) before the proposed effect (Y) does not rule out the possibility of a reversed causal relationship. Two pages after the quote that served as the core argument of Zaman et al.'s objection, Kline8 (p. 207) adds, “time precedence is no guarantee […] because X could have been affected by Y before either variable was actually measured in a longitudinal study.” In other words, measurement order in mediation analysis allows only limited conclusions about the direction of underlying causal relationships. We have previously dealt with this concern in another article that used multilevel mediation analysis to measure the neural mediators of cue-based expectations on subjective pain.1 Although we asked participants in that study about their pain after heat offset, participants might have reflected on ratings before they were explicitly asked, and introspection might have led to brain activation. We reversed mediator and effect variables and found no evidence of mediation, supporting our directional path analyses. Prompted by Zaman et al.'s letter, we now present the same analysis for our recent study.11 Testing both tasks and outcome measures, we compared our original path model (temperature → pain → autonomic nervous system response) with the alternative model (temperature → autonomic nervous system → pain). We find evidence for mediation in both models (Table 1). However, our original model accounts for larger reductions in direct effects than the alternative model. In our original model, pain mediates a substantial amount of the effect of temperature on skin conductance response. By contrast, in the alternative model, autonomic responses account for hardly any variance in the direct effect of temperature on pain, which suggests a direct and strong effect of temperature on pain that autonomic responses are not able to account for. However, we refrain taking too much stock in these findings because of the limitations of model comparison with alternative mediation models,9,14 as discussed by Zaman et al.

Table 1.

Original and alternative mediation models.

Finally, we concur wholeheartedly that expectation, attention, and anxiety1,3,12 can cause variations in pain and physiological arousal beyond the pure effects of temperature, as we discussed.11 In previous work, we directly manipulated and measured the influence of such factors on pain and skin conductance.1,2 However, we believe these processes simply serve as additional links in our proposed causal chain rather than as confounding third variables.

Most importantly, we believe that the directional model and our use of mediation analysis to test this model are defensible because we start with a theoretically strong, a priori, research question, specifically whether or not conscious pain appraisal contributes to the effects of noxious input on autonomic responses. Mediation analysis enables us to make judgments about these possibilities and suggests that pain appraisal does account for variance in this relationship. Although our study was not designed to isolate additional psychological processes that contribute to pain, and our results alone cannot preclude the possibility of reversed or reciprocal associations between pain and autonomic arousal, our work links arousal more closely with pain than nociception and isolates important candidates for targeted interventions in the future.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

L.Y. Atlas is supported by the Intramural Research program of NIH's National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

References

- [1].Atlas LY, Bolger N, Lindquist MA, Wager TD. Brain mediators of predictive cue effects on perceived pain. J Neurosci 2010;30:12964–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Atlas LY, Doll BB, Li J, Daw ND, Phelps EA. Instructed knowledge shapes feedback-driven aversive learning in striatum and orbitofrontal cortex, but not the amygdala. Elife 2016;5:e15192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bantick SJ, Wise RG, Ploghaus A, Clare S, Smith SM, Tracey I. Imaging how attention modulates pain in humans using functional MRI. Brain 2002;125:310–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bullock JG, Green DP, Ha SE. Yes, but what's the mechanism? (don't expect an easy answer). J Pers Soc Psychol 2010;98:550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Damasio AR. Descartes' error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Putnam, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fiedler K, Schott M, Meiser T. What mediation analysis can (not) do. J Exp Soc Psychol 2011;47:1231–6. [Google Scholar]

- [7].IASP. IASP Taxonomy. 2012. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy#Pain. Accessed 13 June, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kline RB. The mediation myth. Basic Appl Soc Psych 2015;37:202–13. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lemmer G, Gollwitzer M. The “true” indirect effect won't (always) stand up: when and why reverse mediation testing fails. J Exp Soc Psychol 2017;69:144–9. [Google Scholar]

- [10].MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci 2000;1:173–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mischkowski D, Palacios-Barrios EE, Banker L, Dildine TC, Atlas LY. Pain or nociception? Subjective experience mediates the effects of acute noxious heat on autonomic responses. PAIN 2018;159:699–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ploghaus A, Narain C, Beckmann CF, Clare S, Bantick S, Wise R, Matthews PM, Rawlins JNP, Tracey I. Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network. J Neurosci 2001;21:9896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Spencer SJ, Zanna MP, Fong GT. Establishing a causal chain: why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. J Pers Soc Psychol 2005;89:845–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Thoemmes F. Reversing arrows in mediation models does not distinguish plausible models. Basic Appl Soc Psych 2015;37:226–34. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vancouver JB, Carlson BW. All things in moderation, including tests of mediation (at least some of the time). Organ Res Methods 2015;18:70–91. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zaman J, Van Oudenhove L, Van Diest I. About the limits of mediation analyses in solving chicken-versus-egg-like type of questions. PAIN 2019:160;1484–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]