Abstract

Hypothesis:

The vestibular aqueduct (VA) in Menière's disease (MD) exhibits different angular trajectories depending on the presenting endolymphatic sac (ES) pathology, i.e., 1) ES hypoplasia or 2) ES degeneration.

Background:

Hypoplasia or degeneration of the ES was consistently found in inner ears affected by MD. The two etiologically distinct ES pathologies presumably represent two disease “endotypes,” which may be associated with different clinical traits (“phenotypes”) of MD. Recognizing these endotypes in the clinical setting requires a diagnostic tool.

Methods:

1) Defining the angular trajectory of the VA (ATVA) in the axial plane. 2) Measuring age-dependent normative data for the ATVA in postmortem temporal bone histology material from normal adults and fetuses. 3) Validating ATVA measurements from normative CT imaging data. 4) Correlating the ATVA with different ES pathologies in histological materials and CT imaging data from MD patients.

Results:

1) The ATVA differed significantly between normal adults and MD cases with ES degeneration, as well as between fetuses and MD cases with ES hypoplasia; 2) a strong correlation between ATVA measurements in histological sections and CT imaging data was found; 3) a correlation between the ATVA, in particular its axial trajectory in the opercular region (angle αexit), with degenerative (αexit < 120°) and hypoplastic ES pathology (αexit > 140°) was demonstrated.

Conclusion:

We established the ATVA as a radiographic surrogate marker for ES pathologies. CT-imaging-based determination of the ATVA enables endotyping of MD patients according to ES pathology. Future studies will apply this method to investigate whether ES endotypes distinguish clinically meaningful subgroups of MD patients.

Keywords: Computed tomography, Endolymphatic sac, Endotype, Menière, Vestibular aqueduct

Patients with Menière's disease (MD) demonstrate a high degree of interindividual variability in the presentation of audiovestibular symptoms (1,2). This variability has previously raised the questions of whether distinct disease phenotypes exist among patients and whether those phenotypes are caused by different endotypes—i.e., different pathologies affecting the inner ear (2,3). A recent human pathology study (4) was the first to demonstrate two etiologically distinct inner ear pathologies (suspected endotypes) that both affect the endolymphatic sac (ES) (Fig. 1A) and are ubiquitously present among MD patients: 1) degenerative change in the ES (54.2% of cases) and 2) developmental hypoplasia of the ES (37.5% of cases). Correlations with clinical record data suggest that these ES pathologies (endotypes) are associated with different clinical traits (phenotypes). To further investigate the presence of discrete endotype–phenotype patterns based on ES pathologies in patients, clinically applicable methods are necessary to distinguish degenerative versus hypoplastic ES pathology.

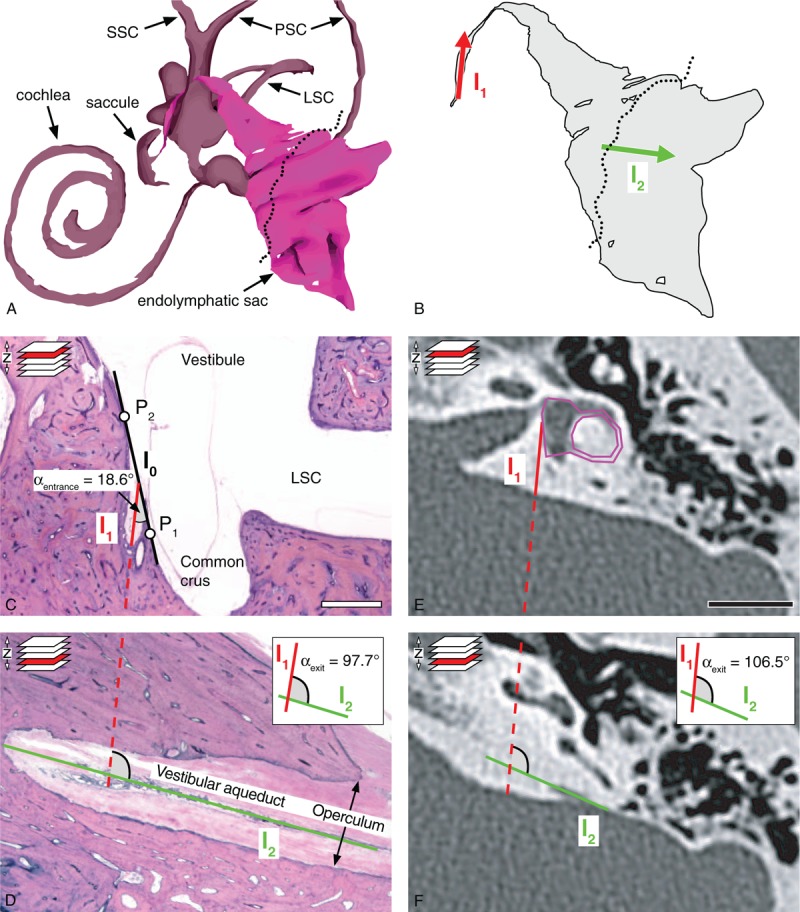

FIG. 1.

Methods to determine αentrance and αexit, i.e., the angular trajectory of the vestibular aqueduct (ATVA), in histological sections and CT images. A, 3D reconstruction of the endolymphatic space of a human (normal adult) inner ear. The dotted line indicates the opening of the opercular region. B, Endolymphatic duct and endolymphatic sac. Lines l1 (red) and l2 (green) used for assessing αexit are indicated. C and D, Histological assessment of αexit in a normal adult temporal bone. E and F, Software-based method to determine αexit from temporal bone CT images. See text for details. Scale bars: (D and E) 1 cm. CT indicates computed tomography; LSC, lateral semicircular canal; PSC, posterior semicircular canal; SCC, superior semicircular canal. Images of 3D models for A and B have been adapted from the 3D temporal bone model of the Eaton-Peabody Laboratory Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA (5).

Here, we used postmortem temporal bone sections from MD cases and CT imaging data from clinical MD patients to investigate whether different ES pathologies (degeneration versus hypoplasia) are associated with different angular trajectories of the vestibular aqueduct (ATVAs) in the temporal bone. The goal of this study was to establish the ATVA as a radiographic marker to distinguish degenerative from hypoplastic ES pathology in clinical MD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics

This study was approved by the institutional Review Board of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary (IRBNet-ID 880454-1; Boston, MA).

Archival Human Temporal Bone Specimens

From the human pathology collection at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, a total of 136 temporal bone specimens were included from cases with normal age-related audiometric threshold patterns and no history of otologic disease (n = 62), fetuses (abortion samples) with no histological signs of developmental defects (n = 42), and cases with a clinical diagnosis of definite MD (n = 32) (Table 1). All specimens were processed for light microscopy using previously described methods (6).

TABLE 1.

Groups of cases and patients

| Study Groups | Specimens (Cases) | Modality | Age in Years (Mean ± SD), Except for Fetuses | Sex Distribution (Males, Females) |

| Normal adults (pathology cases) | 46 (43) | Histology | 55.8 ± 22.3a | 25 (58.1%), 18 (41.9%) |

| Normal adults (pathology cases) with available CT scans | 16 (9) | Histology and CT | 74.6 ± 17.0a | 4 (44.4%), 5 (55.6%) |

| Normal adults (clinical patients) | 64 (35) | CT | 47.7 ± 16.5b; p = 0.18c | 16 (45.7%), 19 (54.3%); p = 0.27 |

| Fetuses (pathology cases) | 44 (22) | Histology | Range: 6–38 weeks | n.a. |

| MD, degenerated ES (pathology cases) | 18 (16) | Histology | 76.5 ± 20.1a | 4 (25.0%), 12 (75.0%) |

| MD, hypoplastic ES (pathology cases) | 14 (9) | Histology | 82.9 ± 11.2a | 6 (66.7%), 3 (33.3%) |

aAt time of death.

bAt time of CT scan.

cP-value of difference between normal adult pathology cases (histology) and normal adult clinical cases (CT).

ES indicates endolymphatic sac; MD, Menière's disease; n.a., data not available.

Temporal Bone CT Imaging Data From Archival Specimens and From Clinical Patients

CT scans of postmortem temporal bone specimens were obtained after tissue removal and fixation and before decalcification, using standard protocols for dedicated high-resolution temporal bone imaging. High-resolution or cone-beam CT imaging of the temporal bones from clinical patients (n = 35; Table 1), all of whom were scanned for suspected diseases not related to the inner ear, was performed without intravenous contrast. All data were reconstructed separately for each temporal bone in the axial plane by using a standard bone algorithm.

Endolymphatic Sac Histopathologies in MD

The histological criteria for degenerative and hypoplastic ES pathology have been described previously (4). Briefly, in degenerative ES pathology, the epithelium in the distal (extraosseous) ES portion exhibits degenerative changes, i.e., pycnotic nuclei, expelled/missing cells, and fibrotic replacement. In hypoplastic ES pathology, the ES is not properly developed and lacks an extraosseous portion.

All specimens with degenerative (n = 18) and hypoplastic ES pathology (n = 14) that were used in the present study have been previously characterized (4).

ATVA Measurements in Histological Sections

The ATVA was determined in horizontally sectioned temporal bone specimens by measuring 1) the entrance trajectory (red arrow, Fig. 1B) of the proximal VA portion into the temporal bone (angle “αentrance”) and 2) the trajectory along which the VA exits the temporal bone (green arrow, Fig. 1B) in the opercular region (angle “αexit”). To determine αentrance (Fig. 1C), we used two points (P1 and P2) on the medial wall of the vestibule, with a distance to the internal orifice of the VA of approximately 1 mm, to define a line l0. A second line l1 was set to run across the orifice, parallel to the most proximal part of the VA. αentrance is the acute angle enclosed by the lines l0 and l1. αexit was determined in a different, more caudally located section plane in the opercular region (Fig. 1D). Here, a line l2 was placed parallel to the most distal part of the VA. αexit is the angle enclosed by lines l1 from Figure 1C and l2, which were merged in a virtual plane (Fig. 1D, inset). αentrance was measured using the angle measurement tool of the software Fiji (7). αexit was determined using a custom-designed software (see next paragraph and PDF file, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

ATVA Measurements in CT Images

We modified the method used on histological sections (previous paragraph) for ATVA measurements, since, due to the limits of image resolution, CT did not provide reliable visualization of the VA at its origin from the vestibule. Hence, αentrance could not be determined in CT images. Instead, a predefined shape (magenta shape, Fig. 1E) was congruently fitted into the bony boundaries of the vestibule and the lateral semicircular canal in the appropriate image plane. The proportions of the shape were determined on an axial CT image from a normal adult temporal bone in which the entire vestibule and lateral semicircular canal were visible. Fitting this shape to more than 100 CT image data sets in this study required only very minor adjustments to the shape's side ratios, confirming its overall good fit to the normal adult temporal bone anatomy. The line l1 was attached to this shape at a fixed angle of 14.0 degrees, representing the average αexit, as determined from histological sections from normal adult controls (see Results section). Analogous to the method used on histological sections, a line l2 was set to run parallel to the most distal part of the VA in the opercular region in a more caudally located image plane (Fig. 1F). αexit is the angle between lines l1 and l2 (Fig. 1F, inset).

Software for ATVA Measurements

A custom-made open-source web application was developed for angle measurements from CT imaging data. The software is freely available for download at https://github.com/DanielZuerrer/CoolAngleCalcJS or as an online version at https://danielzuerrer.github.io/CoolAngleCalcJS. An illustrated step-by-step manual for angle measurements is provided as digital supplemental material (Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the software Prism (version 7.0a; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). For group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance was performed, along with post hoc multiple comparison testing by the Holm–Sidak method. For comparison of αexit (CT images and histological sections) from adult controls, Student's unpaired two-sample t test was used. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was determined to assess correlations between values for the αexit as determined from histological sections and CT images from adult controls. For all angles, mean values, and standard deviations are reported. The significance level was set to p < 0.05.

RESULTS

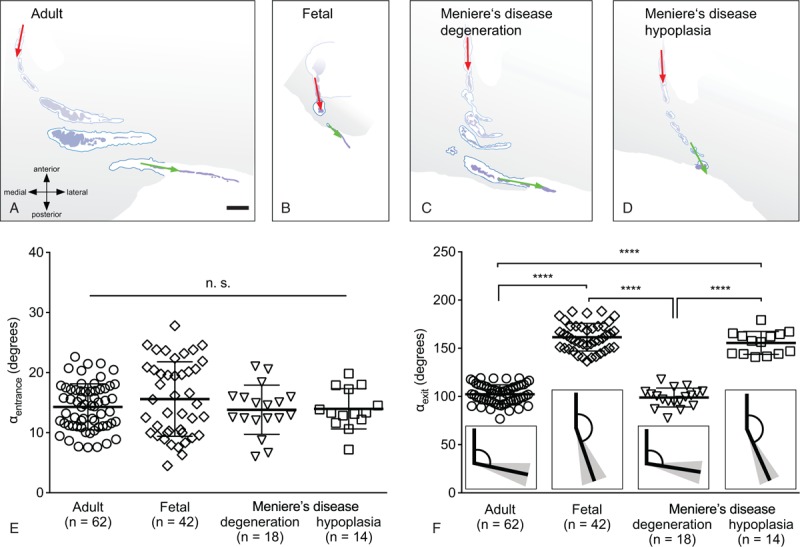

The ATVA in Temporal Bone Histology: Normal Adults and Fetuses

Normative data for the ATVA (αentrance and αexit) were determined from histological temporal bone sections. αentrance did not differ significantly between normal adults (2D-reconstructed course of a representative VA, Fig. 2A) and fetuses (Fig. 2B) (adults: 14.3 ± 3.8 degrees, range 7.6–22.6 degrees, n = 62; fetuses: 15.6 ± 6.2 degrees, range 4.5–27.8 degrees, n = 42; p = 0.67; Fig. 2E). In contrast, αexit was significantly narrower in normal adults than in fetuses (adults: 102.3 ± 9.8 degrees, range, 76.8–119.1 degrees, n = 62; fetuses: 161.5 ± 14.3 degrees, range, 136.6–188.3 degrees, n = 42; p < 0.0001; Fig. 2F). In fetuses, no significant correlation was found between αexit and gestational age (p = 0.10).

FIG. 2.

Angular trajectory of the vestibular aqueduct (ATVA, i.e., αentrance and αexit) measurement in normal adults, fetuses, and Menière's disease (MD) cases. (A–D) 2D-reconstructed course of the right vestibular aqueduct from multiple (3–6) histological sections in a normal adult case (79 years; A), a fetus (gestational week 8; B), an MD case with a degenerated endolymphatic sac (ES) (94 yr; C), and an MD case with a hypoplastic ES (97 yr; D). (E and F) Values of αentrance (E) and αexit (F) in normal adults, fetuses, and MD cases (degenerated ES, hypoplastic ES). Insets in (F) illustrate the mean angle (black lines) and the corresponding standard deviations (gray-shaded areas). Statistics: ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; CT indicates computed tomography; n.s., not significant. Scale bar: (A–D) 1 mm.

The ATVA in Temporal Bone Histology: Cases With Menière's Disease

In endotyped MD cases (representative VA morphologies shown in Fig. 2C and D) αentrance was determined from histological sections. αentrance was not significantly different between the two groups (degenerated ES: 13.8 ± 4.1 degrees, range, 6.0–21.1 degrees, n = 18; hypoplastic ES: 14.0 ± 3.4 degrees, range, 7.2–19.8 degrees, n = 14; p = 0.97), and neither group significantly differed from normal adults or fetuses (Fig. 2F). In contrast, αexit was significantly different between the two MD groups (degenerated ES: 98.9 ± 9.8 degrees, range, 77.5–117.7 degrees, n = 18; hypoplastic ES: 155.6 ± 11.9 degrees, range, 140.9–179.3 degrees, n = 14; p < 0.0001). Similar values for αexit (no statistical significance) were found between MD cases (degenerated ES) and normal adults, as well as between MD cases (hypoplastic ES) and fetuses (Fig. 2F).

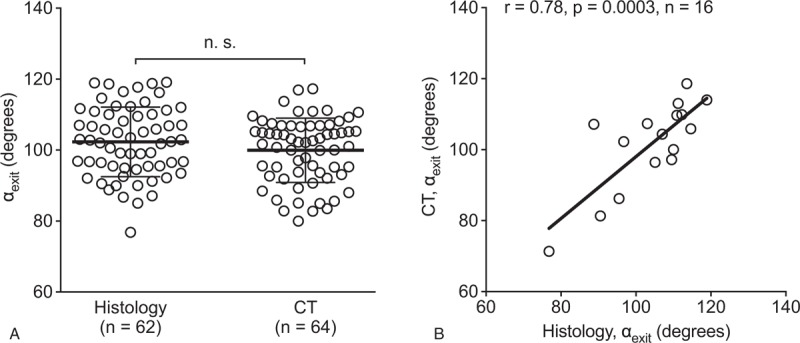

Correlating the ATVA Between Histology and CT: Normal Adults

To validate ATVA measurements in CT imaging data, we first compared values for αexit determined in temporal bone sections from a group of normal adult cases with values determined in CT images from an unrelated group (no significant age or sex differences, Table 1) and found no significant differences (histology: 102.3 ± 9.8, range, 76.8–119.1, n = 62, data shown in Fig. 2F; CT: 99.9 ± 9.1 degrees, range, 80.0–117.3 degrees, n = 64; p = 0.21; Fig. 3A). Next, we determined αexit from 16 temporal bone specimens that were scanned before histological processing. Values determined from CT images and the corresponding histological sections showed a strong correlation (r = 0.78, p = 0.0003; Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Normal αexit assessed in histology and CT imaging data. A, αexit as determined in two independent groups (first group: histology; second group: CT images). B, Correlation of angle values as determined from histological sections and CT images derived from the same temporal bone specimens. CT indicates computed tomography; n.s., not significant.

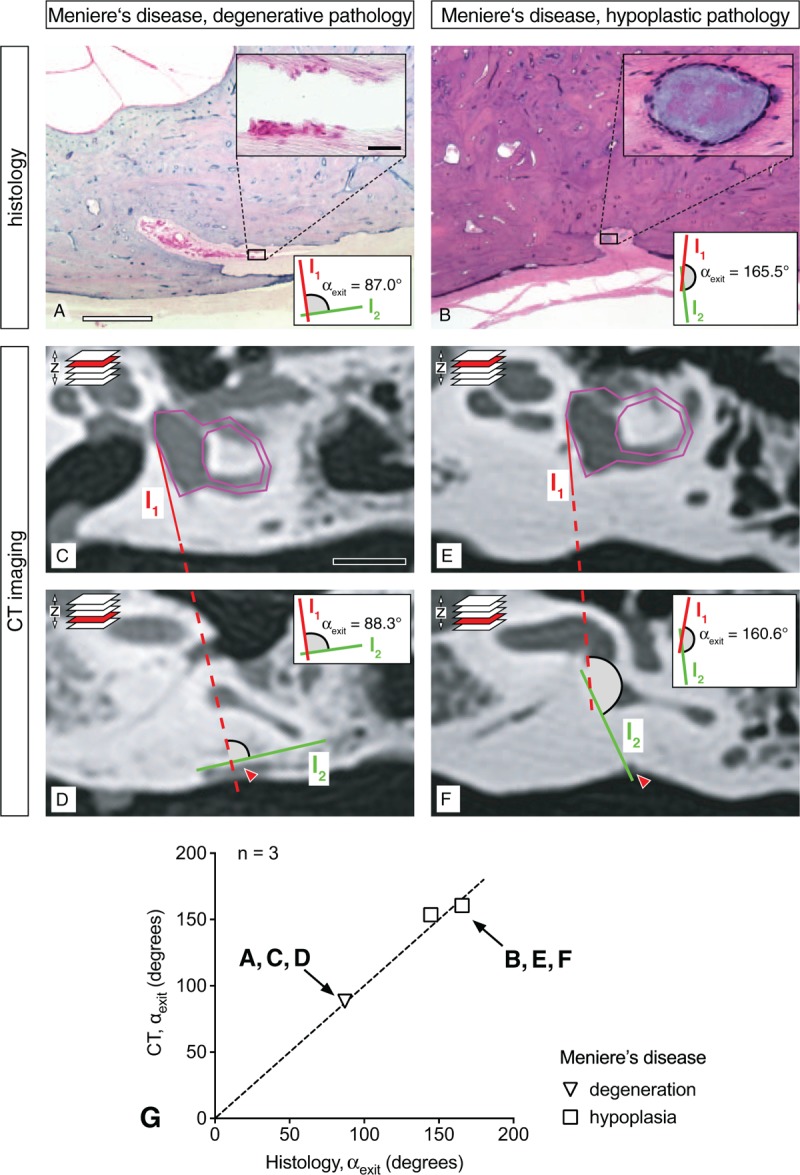

Correlating the ATVA Between Histology and CT: Cases With Menière's Disease

To investigate whether the ATVA can be determined in MD cases with degenerative versus hypoplastic ES pathology, we used three postmortem temporal bone specimens from two MD cases that underwent CT imaging before histological processing. Histology demonstrated unilateral degenerative pathology in the first case (Fig. 4A) and bilateral hypoplastic ES pathology in the second case (Fig. 4B). Measurements of αexit in both modalities (degenerated ES: Fig. 4C and D; hypoplastic ES: Fig. 4E and F) yielded very similar results with discrepancies of less than 10 degrees (histology – degenerated ES: 87.0 degrees; histology – hypoplastic ES: 165.5 degrees on the left side and 144.6 degrees on the right side; CT – degenerated ES: 88.3 degrees; CT – hypoplastic ES: 160.6 degrees on the left side and 153.6 degrees on the right side; Fig. 4G).

FIG. 4.

Correlation of endolymphatic sac (ES) pathology and αexit (histology and CT imaging) in Menière's disease (MD). A and B, Histological sections (opercular region) from a case of degenerative ES pathology (A; inset: degenerated ES epithelium) and a case of hypoplastic ES pathology (B; inset: cyst-like distal end of the ES). (C–F) CT images from the same specimens as in (A) and (B) in the axial focal plane of the opercular region. (E) Correlation of values for the αexit as determined in CT images and histological sections from the same specimens (n = 3, from two MD cases). Dashed line indicates 100% correlation (r = 1); scale bars: (A–B) 1 mm, inset in (A–B) 50 μm, (C–D) 10 mm. Red arrows in (C–F) indicate the opercular region. CT indicates computed tomography.

DISCUSSION

Numerous previous studies have attempted to identify disease-specific morphological alterations of the VA in MD based on intraoperative anatomy (8), postmortem histology (9–11), CT imaging (12–17), or MRI (18–21). However, those studies did not consider distinct etiologies (endotypes) of MD or their potentially different effects on VA morphology. Moreover, those previous studies that used clinical imaging (CT/MRI) required elaborate postprocessing methods (e.g., 3D reconstructions, (22)) to determine morphological parameters of the VA.

Here, we established the ATVA, in particular the angle αexit, as a surrogate marker of ES pathologies (histopathological endotypes) in MD (Table 2). By correlating ATVA measurements from histologically processed temporal bones and from CT imaging data, we demonstrated that the ATVA can be reliably determined using clinical imaging data. Our measurements indicated 1) no significant differences in the trajectory of the proximal VA portion (αentrance) among all investigated groups, 2) a significant change in the trajectory of the distal VA portion (αexit) between the fetal and adult stages of normal temporal bone development, 3) a similar (no significant difference) αexit between fetal cases and MD cases with hypoplastic ES pathology, and 4) a similar (no significant difference) αexit between normal adult cases and MD cases with degenerative ES pathology.

TABLE 2.

Proposed endolymphatic sac pathology-based endotyping

| Clinical Diagnosis | Disease Lateralitya | αexit (Affected/Non-Affected) | Endotype Diagnosis |

| Definite Menière's disease | Unilateral | >140 degrees/<120 degrees | Unilateral hypoplastic |

| <120 degrees/<120 degrees | Unilateral degenerative, bilateral degenerativeb | ||

| >140 degrees/>140 degrees | Bilateral hypoplasticb | ||

| Bilateral | <120 degrees/<120 degrees | Bilateral degenerative | |

| >140 degrees/>140 degrees | Bilateral hypoplastic |

aAt time of study.

bWith initial unilateral clinical presentation.

The observed changes in VA morphology (angle αexit) during ontogenesis (fetal versus adult VA; [(23), present study]) and between MD endotypes (degenerative versus hypoplastic ES pathology; present study) may be attributable to temporal and spatial differences in bone growth and development of the petrous bone. The definite size and shape of the bony labyrinth during ontogenesis is thought to be strongly influenced by a decline in the rate of bone metabolism (bone remodeling) in the otic capsule (24), which occurs around the 23rd fetal week (25). At that time point, cells of the membranous labyrinth are presumably starting to secret osteoprotegerin (OPG), an inhibitor of osteoclast activity, into the perilymphatic fluid spaces, from which the OPG diffuses into the surrounding bone (limited by the diffusion gradient) to inhibit bone matrix remodeling (24). Notably, the distal portion of the VA—which undergoes significant morphological changes between the 19th and 23rd fetal week ((23,25), present study)—extends beyond the otic capsule and passes through a layer of normally remodeling (lamellar) bone to the operculum. Prolonged bone growth and continuous bone remodeling in the opercular region during the postnatal period can explain the delayed morphological maturation of the distal VA (compared with the rest of the bony labyrinth), as well as its highly variable morphology in the adult stage (22,26–28).

In the present study, we found that different MD endotypes were associated with significantly different VA morphologies and that the latter resembled very different morphological stages during normal temporal bone development. Hypoplastic ES pathology was associated with an abnormally short, straight VA (αexit > 140°), as found in fetal (gestational weeks 6–38) developmental stages. This premature VA morphology, together with a hypoplastic ES, supports a genetic/developmental etiology in this endotype, as proposed by Eckhard et al. (4). With αexit consistently more than 140 degrees, we defined a specific imaging-based diagnostic criterion for this endotype. In contrast, the normal (mature) VA morphology in MD cases with degenerative ES pathology suggests an etiology that manifests in adult life and that causes progressive ES degeneration (but does not affect the VA) (4). The range for the angle αexit in this MD endotype was similar to the range observed in normal (adult) morphology. Hence, αexit does not provide a specific diagnostic criterion for this endotype.

In conclusion, determining the ATVA (αexit) from clinical imaging data enables endotyping of MD patients according to the underlying ES pathology. This approach will be applied in future studies to stratify MD patients according to their endotype and to elucidate whether those endotypes determine clinically meaningful, i.e., phenotypically different, patient subgroups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the exceptional technical expertise of Barbara Burgess, Diane Jones, Jennifer O’Malley, and MengYu Zhu in preparing the human temporal bone specimens. They also thank Reef Al-Asad for the technical assistance in angle measurements.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J.C.A. and A.H.E. conceived and designed the study. D.Z. and D.B. designed the software for angle measurements. D.B. and N.L. conducted the measurements. D.B., S.B., and A.H.E. prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. J.S.K., D.J.L., and H.D.C. provided CT imaging data from clinical cases. J.S.K., D.J.L., S.D.R., J.C.N., and J.C.A. provided critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the American Hearing Research Foundation and the GEERS Foundation (S030 – 10.051). The author AHE was supported by a Research fellowship grant (EC 472/1) from the German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft). The author DB was supported by a Graduate Campus Travel Grant from the University of Zurich, Switzerland. The author NL was supported by an Emerging Research Grant from the Hearing Health foundation.

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friberg U, Stahle J, Svedberg A. The natural course of Meniere's disease. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1984; 406:72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rauch S. Clinical hints and precipitating factors in patients suffering from Meniere's disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2010; 43:1011–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merchant SN, Adams JC, Nadol JB. Pathophysiology of Meniere's syndrome: are symptoms caused by endolymphatic hydrops? Otol Neurotol 2005; 26:74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckhard AH, Zhu M, O’Malley JT, et al. Inner ear pathologies impair sodium-regulated ion transport in Meniere's disease. Acta Neuropathol 2019; 137:343–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, Northrop C, Burgess B, Liberman MC, Merchant SN. Three-dimensional virtual model of the human temporal bone: a stand-alone, downloadable teaching tool. Otol Neurotol 2006; 27:452–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merchant SN, Nadol JB. Schuknecht's Pathology of the Ear. 3rd ed. USA: People's Medical Pub. House; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 2012; 9:676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitahara T, Yamanaka T. Identification of operculum and surgical results in endolymphatic sac drainage surgery. Auris Nasus Larynx 2017; 44:116–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sando I, Ikeda M. The vestibular aqueduct in patients with Meniere's disease: a temporal bone histopathological investigation. Acta Otolaryngol 1984; 97:558–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda M, Sando I. Endolymphatic duct and sac in patients with Meniere's disease: a temporal bone histopathological study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1984; 93:540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuen SS, Schuknecht HF. Vestibular aqueduct and endolymphatic duct in Meniere's disease. Arch Otolaryngol 1972; 96:553–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clemis JD, Valvassori GE. Recent radiographic and clinical observations on the vestibular aqueduct (a preliminary report). Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1968; 1968:339–346. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emery PJ, Gibson WR, Lloyd GA, Phelps PD. Polytomography of the vestibular aqueduct in patients with Meniere's disease. J Laryngol Otol 1983; 97:1007–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nidecker A, Pfaltzb CR, Matéfi L, Benz UF. Computed tomographic findings in Ménière's disease. ORL 1985; 47:66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazawa Y, Kitahara M. Computed tomographic findings around the vestibular aqueduct in Meniere’ disease. Acta Otolaryngol 1991; 111:88–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krombach GA, van den Boom M, Di Martino E, et al. Computed tomography of the inner ear: size of anatomical structures in the normal temporal bone and in the temporal bone of patients with Menière's disease. Eur Radiol 2005; 15:1505–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maiolo V, Savastio G, Modugno GC, Barozzi L. Relationship between multidetector CT imaging of the vestibular aqueduct and inner ear pathologies. Neuroradiol J 2013; 26:683–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xenellis J, Vlahos L, Papadopoulos A, Nomicos P, Papafragos K, Adamopoulos G. Role of the new imaging modalities in the investigation of Meniere's disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000; 123 (1 pt 1):114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inui H, Sakamoto T, Ito T, Kitahara T. Volumetric measurements of the inner ear in patients with Meniere's disease using three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Otolaryngol 2016; 136:888–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel VA, Oberman BS, Zacharia TT, Isildak H. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in Ménière's disease. J Laryngol Otol 2017; 131:602–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugihara EM, Marinica AL, Vandjelovic ND, et al. Mastoid and inner ear measurements in patients with Menière's disease. Otol Neurotol 2017; 38:1484–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujita S, Sando I. Three-dimensional course of the vestibular aqueduct. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1996; 253:122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watzke D, Bast TH. The development and structure of the otic (endolymphatic) sac. Anat Rec 1950; 106:361–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zehnder AF, Kristiansen AG, Adams JC, Merchant SN, McKenna MJ. Osteoprotegerin in the inner ear may inhibit bone remodeling in the otic capsule. Laryngoscope 2005; 115:172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donaldson J, Duckert L, Lambert P, Rubel E. Anson BJ, Donaldson JA. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Surgical Anatomy of the Temporal Bone. 4th ed. New York, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilbrand HF, Rask-Andersen H, Gilstring D. The vestibular aqueduct and the para-vestibular canal. An anatomic and roentgenologic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1974; 15:337–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arenberg IK, Rask-Andersen H, Wilbrand H, Stahle J. The surgical anatomy of the endolymphatic sac. Arch Otolaryngol 1977; 103:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordström CK, Laurell G, Rask-Andersen H. The human vestibular aqueduct: anatomical characteristics and enlargement criteria. Otol Neurotol 2016; 37:1637–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.