Abstract

Background

Femoral stems with bimodular (head-neck as well as neck-body) junctions were designed to help surgeons address patients’ hip anatomy individually. However, arthroplasty registers have reported higher revision rates in stems with bimodular junctions than in stems with modularity limited to the head-neck trunnion. However, to our knowledge, no epidemiologic study has identified patient-specific risk factors for modular femoral neck fractures, and some stems using these designs still are produced and marketed.

Questions/purposes

The purposes of this study were (1) to establish the survival rate free from aseptic loosening of one widely used bimodular THA design; (2) to define the proportion of patients who experienced a fracture of the stem’s modular femoral neck; and (3) to determine factors associated with neck fracture.

Methods

In this retrospective, nationwide, multicenter study, we reviewed 2767 bimodular Profemur® Z stems from four hospitals in Slovenia with a mean followup of 8 years (range, 3 days to 15 years). Between 2002 and 2015, the four participating hospitals performed 26,132 primary THAs; this implant was used in 2767 of them (11%). The general indications for using this implant were primary osteoarthritis (OA) in 2198 (79%) hips and other indications in 569 (21%) hips. We followed patients from the date of the index operation to the date of death, date of revision, or the end of followup on March 1, 2018. We believe that all revisions would be captured in our sample, except for patients who may have emigrated outside the country, but the proportion of people immigrating to Slovenia is higher than the proportion of those emigrating from it; however, no formal accounting for loss to followup is possible in a study of this design. There were 1438 (52%) stems implanted in female and 1329 (48%) in male patients, respectively. A titanium alloy neck was used in 2489 hips (90%) and a cobalt-chromium neck in 278 (10%) hips. The mean body mass index (BMI) at the time of operation was 29 kg/m2 (SD ± 5 kg/m2). We used Kaplan-Meier analysis to establish survival rates, and we performed a chart review to determine the proportion of patients who experienced femoral neck fractures. A binary logistic regression model that controlled for the potential confounding variables of age, sex, BMI, time since implantation, type of bearing, diagnosis, hospital, neck length, and neck material was used to analyze neck fractures.

Results

There were 55 (2%) aseptic stem revisions. Survival rate free from aseptic loosening at 12 years was 97% (95% confidence interval [CI] ± 1%). Fracture of the modular neck occurred in 23 patients (0.83%) with a mean BMI of 29 kg/m2 (SD ± 4 kg/m2.) Twenty patients with neck fractures were males and 19 of 23 fractured necks were long. Time since implantation (odds ratio [OR], 0.55; 95% CI 0.46-0.66; p < 0.001), a long neck (OR, 6.77; 95% CI, 2.1-22.2; p = 0.002), a cobalt-chromium alloy neck (OR, 5.7; 95% CI, 1.6-21.1; p = 0.008), younger age (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86-0.96; p < 0.001), and male sex (OR, 3.98; 95% CI, 1.04-14.55; p = 0.043) were factors associated with neck fracture.

Conclusions

The loosening and neck fracture rates of the Profemur® Z stem were lower than in some of previously published series. However, the use of modular femoral necks in primary THA increases the risk for neck fracture, particularly in young male patients with cobalt-chromium long femoral necks. The bimodular stem we analyzed fractured unacceptably often, especially in younger male patients. For most patients, the risks of using this device outweigh the benefits, and several dozen patients had revisions and complications they would not have had if a different stem had been used.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Femoral stems with multiple modular junctions were designed to help surgeons address the vast differences that are present among patients in terms of leg length, anteversion, and offset, and they have been reported to be especially useful in patients with excessive anteversion or retroversion and developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) [2, 20, 29]. Some studies have purported that these stems allow better hip ROM, muscular strength, and—at least theoretically—a lower dislocation risk [2, 19, 30]. However, two main concerns have been raised about these implants, which have overshadowed any potential benefits of dual modularity [3, 15, 21, 32, 33]. First, corrosion of the neck-stem interface can produce metallic debris, which results in reactions similar to pseudotumors seen with metal-on-metal (MoM) articulations [21]. The second observed adverse effect has been a high fracture risk of the stem’s modular neck [3, 15, 32, 33].

In 2010, three reports of fractures of titanium femoral necks were published, in which all patients were male, two of three had high body mass indices (BMIs), and all had long modular necks [3, 32, 33]; a case series published that year suggested the incidence of this problem was 1.4% [15]. There were also several midterm reports of bimodular femoral stem results [25, 26]. However, many of these stems involved MoM articulations, which can contribute to some of the problems we are concerned about here [4, 25, 26], confounding the analysis. In studies of registries or national cohorts, bimodular stems have higher revision probabilities than fixed neck stems [4, 5], but because not all prosthesis designs behave similarly, it is hard to extrapolate those results to individual designs.

The Profemur® Z bimodular stem (Wright Medical Technology, now MicroPort Orthopedics, Arlington, TN, USA) was introduced in 2002. The Italian Regional Register of the Orthopaedic Prosthetic Implants (RIPO) analysis of the 692 Profemur Z stem presented good 12-year survival results with a 0.3% rate of neck fractures, but the correlation among femoral neck fracture, neck length, and neck material was not presented because these data were missing [10]. Reports of fractures of the titanium alloy necks on Profemur Z long stems resulted in the deployment of a cobalt-chromium (CoCr) alloy neck. Nevertheless, this type of CoCr neck was recalled in 2015 as a result of higher fracture rates [9]. Several bimodular stems, usually manufactured by smaller orthopaedic companies, are still produced and marketed. However, little is known about the risk of stem fracture with these devices [6, 23, 31].

We therefore sought to analyze the Profemur Z stem in the context of a multicenter, nationwide sample, specifically to determine (1) its survivorship free from aseptic loosening; (2) the proportion of patients who received this stem and experienced a fracture of the stem’s modular femoral neck; and (3) the factors associated with neck fracture in THAs that used the Profemur Z stem.

Patients and Methods

The study was approved by the Republic of Slovenia National Medical Ethics Committee on April 25, 2017 (Number 020-231/2017/5).

The study population constituted of 2457 patients (2767 stems; 310 patients had bilateral stems) with primary Profemur Z femoral stems implanted in departments of four hospitals in Slovenia (1024 in Valdoltra Orthopaedic Hospital, 494 in University Medical Centre Ljubljana, 680 University Medical Centre Maribor, and 569 in General Hospital Celje) between 2002 and 2015. During this time, the Profemur Z stem was used as one of the standard stems for treatment of hip osteoarthritis (OA). Between 2002 and 2015, the four participating hospitals performed 26,132 primary THAs; this implant was the only bimodular device used, and it was used in 2767 of them (11%). During that period, the most common indication for using this implant was primary OA (78% of cases), although we believe it is used more commonly among patients with altered femoral anatomy, such as OA resulting from DDH or posttraumatic OA (Table 1). In the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Register (AOANJRR) 2018 report, primary OA accounted for 88% of THAs, DDH for 1%, avascular necrosis for 3%, and other reasons for 1% of THAs, respectively [4]. In our cohort, 10% of hips were operated on for OA resulting from DDH, 4% for posttraumatic OA, and 6% for avascular necrosis, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data and diagnosis at the time of primary THA

We followed patients from the date of the index operation to the date of revision surgery, date of death, or the end of followup on March 1, 2018. We believe that all revisions would be captured in our sample other than for patients who emigrated outside the country. We believe that loss to followup because of emigration is unlikely to have represented a substantial source of bias, because Slovenia has a proportion of immigration higher than emigration [27]; however, no formal accounting for loss to followup is possible in a study of this design.

Patients’ demographic data, primary implant characteristics, reasons for revision, and revised components were identified from the hospitals’ records and from the Valdoltra Arthroplasty Registry [18]. The data from all hospitals were crosschecked to identify revisions performed somewhere other than the primary surgery hospital. Because all Slovenian hospitals that performed revision operations of the Profemur Z stem were included, the data on all revisions performed to the end of followup were available.

Mean followup was 8 years (range, 3 days to 15 years). A total of 1329 (48%) stems were implanted in male patients and 1438 (52%) in female patients. The Profemur Z stem was implanted bilaterally in 310 patients (147 males and 163 females). Mean age of the male patients at the time of the surgery was 60 years (SD ± 10) and females 63 years (SD ± 11) (p < 0.001). The mean BMI at the time of operation was 29 kg/m2 (SD ± 4 kg/m2) in men and 28 kg/m2 (SD ± 5 kg/m2) in women, respectively (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Although BMI was not available for 492 patients, it was known for all revised hips.

The primary Profemur Z was used. It is a straight, uncemented stem with a rectangular cross-section and dual-taper geometry available in nine different sizes (Fig. 1). Its surface is corundum-blasted with a pore roughness of Ra 8 μm. The stem is bimodular with modularity between the head and the neck as well as between the neck and the body of the stem (Fig. 1).The modular neck has 12 different options. The straight neck has a 135° centrum-collum-diaphyseal (CCD) angle (short and long versions). The varus/valgus neck options alter CCD angle by 8° in either direction. Additionally, anteversion and retroversion of the neck can be altered by 8° or 15° in either direction. There are options with a combination of the anteversion/retroversion and a varus/valgus shift. With different lengths and orientations, a total of 22 unique neck combinations are available [26].

Fig. 1.

This figure shows a retrieved Profemur Z stem with a fractured modular neck in place. The insert in the upper left corner shows an oval trunnion after the neck fracture and an attempt to remove the neck piece from the stem.

After we excluded three hips with MoM bearings, five different bearing combinations were used. Ceramic-on-ceramic bearings were used in 682 (25%) hips, ceramic-on-polyethylene (PE) in 333 (12%), ceramic-on-crosslinked polyethylene (XLPE) in 846 (31%), metal-on-PE in 352 (13%), and metal on XLPE in 537 (19%) hips, respectively. The bearing type was unknown in 17 hips (1%). Three basic types of acetabular cups were used: press-fit in 2570 hips, threaded biconical cup in 70 hips, and cemented cup in 122 hips. In five hips, the type of cup was unknown. A total of 2489 (90%) necks were made of titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V). From the end of 2012 onward, the CoCr neck was used in 278 hips (10%). Data about the degree of modular neck anteversion or retroversion (8° or 15°) and varus/valgus orientation of implanted necks are not known.

A total 1037 of 2489 (42%) titanium alloy necks were long (all variants included); in the group of CoCr necks, 244 (88%) of 278 were long (p < 0.001). The direct lateral approach was used in 2486 (90%) and posterior in 281 hips (10%). We used the so-called impact-assembled technique for the assembly of the femoral stem, neck, and head [1]. The standard perioperative prophylactic antibiotic regime consisted of three doses of 1g, first-generation cephalosporin intravenously and standard postoperative antithrombotic prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin for 35 days was used.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated stem survival using the Kaplan-Meier method [16]. Stem failure (any reason/aseptic) was defined as the endpoint of the analysis. We used a log-rank test to analyze revision rates of different lengths of the neck [24].

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and comparisons between the two groups were done by unpaired t-tests. Categorical variables are presented as percentages and the comparisons were done by chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests.

We estimated the association of continuous and ordinal variables with survivorship for aseptic loosening of the stem using the Cox proportional hazards model [7]. We used a binary logistic regression model to analyze the modular neck fracture and the risk factors: patients’ age, sex, time from implantation, length and neck material, articulation, BMI, hospital, and preoperative diagnosis. For the purposes of Cox analysis and binary logistic regression, we distributed necks into two groups: long and short. Probability values < 0.05 were considered significant. For statistical analysis, we used IBM SPSS Statistics , version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) statistical software.

Results

Survivorship

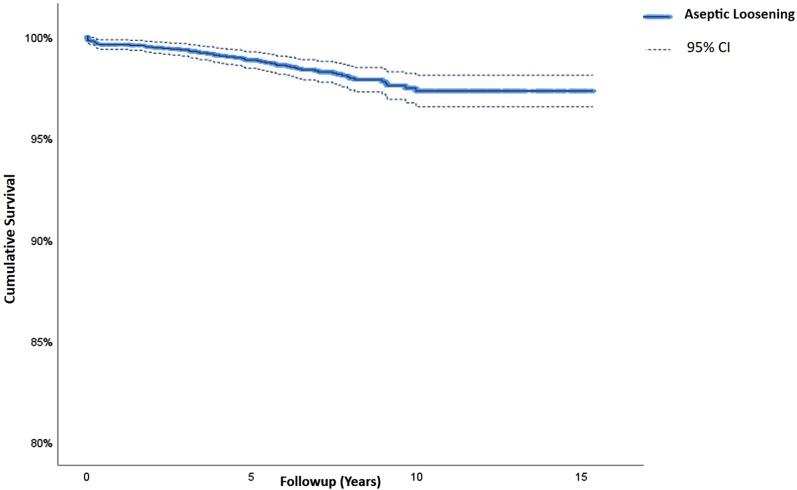

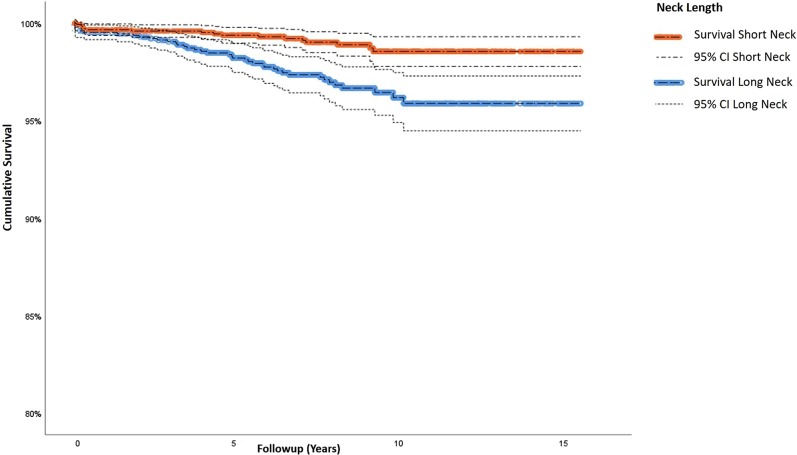

Survivorship free from aseptic loosening at 12 years of the Profemur Z stem in this series was 97% (95% confidence interval [CI], 96%-99%) (Fig. 2). Survival free from aseptic loosening of the stem combined with a long neck was 96% (95% CI, 95%-97%) and 99% (95% CI, 98%-99%) if a short neck was used (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Mean time to revision was 4 years (range, 3 days to 10 years). Main mode of stem failure was neck fracture (Table 2). With the numbers available, the only factor independently associated with aseptic loosening was use of a long modular neck (hazard ratio, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.32-4.48; p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

This Kaplan-Meier survivorship graph shows aseptic revision of the bimodular Profemur Z stem; CI = confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

This Kaplan-Meier survivorship graph shows aseptic revision of the bimodular Profemur Z stem combined with short or long neck; CI = confidence interval.

Table 2.

Data regarding stem failure

Modular Femoral Neck Fractures

There were 23 fractures of the modular femoral neck in the 2767 stems analyzed (0.83%). Nineteen (0.68%) fractured necks were long and four (0.14%) were short. Fractures occurred in 19 of 2489 titanium alloy necks (0.76%) and in four CoCr necks of 278 used (1.44%). Mean time of neck fracture (both alloys) was 4.7 years (SD ± 2.2 years) With the available numbers, we found no difference between CoCr necks and Ti necks in terms of time to fracture: 3.4 years (SD ± 1.4) versus 5 years (SD ± 2.3; p = 0.198). Twenty of 1329 (1.5%) patients with neck fracture were male and three of 1438 (0.2%) were female (p < 0.001). Mean BMI of the patients with fractured necks was 29 kg/m2 (SD ± 4 kg/m2).

Factors Associated With Modular Neck Fracture

Controlling for the potential confounding variables of age, sex, time since implantation, length and neck material, articulation, BMI, hospital, and preoperative diagnosis, we found time since implantation (odds ratio [OR], 0.55; 95% CI, 0.46-0.66; p < 0.001), younger age (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86-0.96; p < 0.001), long femoral necks (OR, 6.77; 95% CI, 2.1-22.2; p = 0.002), CoCr necks (OR, 5.7; 95% CI, 1.6-21.1; p = 0.008), and male sex (OR, 3.89; 95% CI, 1.04-14.55; p = 0.043) were associated with an increased risk of neck fracture.

Discussion

Bimodular stems saw wide use for awhile but have fallen into relative disuse because of serious clinical problems, including fractures and recalls of major stem designs [9, 12, 13, 15]. Still, they deserve our attention because some newer designs—the use of which is supported only with rare observational studies—are still marketed as superior to older ones [23]. Modular neck failure is a catastrophe for the patient. It may also become a serious problem for the healthcare system if the implanted bimodular necks would fail on a widespread basis over time. We therefore sought to arrive at more precise estimates of the frequency and risk factors of modular neck fractures in these THAs by looking at the experience across one country. We found that neck fracture occurred in 0.83% of hips and was asssociated with younger age, male sex, and CoCr alloy necks. Because this is a complication that is nearly unheard of in other stem designs, we conclude that modular necks are unnecessary for routine use in primary THA.

Our study has several limitations that are worth considering. First, we believe that the Profemur Z bimodular stem was commonly selected for more demanding hips (dysplasia, avascular necrosis, and posttraumatic OA) and/or in younger, more active patients. However, we do not know the actual postoperative activity level of these patients. Second, the data were obtained from four biggest primary and revision orthopaedic centers, but one smaller hospital was not included in the study and did approximately 200 Profemur Z stems during the observational period. Revisions of failed THAs are not performed in this hospital. We detected one femoral neck fracture among the THAs performed at this hospital, but we did not include this patient in our analysis. Apart from that one, we believe we accounted for all revisions that were performed on these implants in our country during the study period; we could not account for emigration, but for the reasons noted earlier, we do not believe this would have changed the results in any substantial way. Third, the symmetrically oval trunnion design of the Profemur Z allowed varus or valgus orientation of the modular femoral neck, but the exact orientation of the implanted neck as well as the degree of modular neck anteversion or retroversion could not be retrieved from the patients’ records, so we could not analyze the association of neck orientation on fracture risk. We do acknowledge that because of the aforementioned issues of selection and transfer bias, the results of the stem may look better than they are in reality.

Survival probability of the stem in our series at 12 years was 97% free from aseptic loosening. Although some smaller studies found satisfactory results [28], larger nationwide studies confirmed that modularity does not bring added value to primary THA (Table 3). One such study, involving 324,108 patients (8931 with bimodular stems), found that patients with modular femoral neck THA prostheses were more likely to undergo revision than those with fixed neck stems [5].

Table 3.

Clinical studies and registries reports published on bimodular stems

The overall femoral neck fracture rate in our series was 0.83% (23 of 2767 hips). It was higher for CoCr alloy stems (1.44%) than for titanium alloy necks (0.76%). It occurred in 19 long and four short necks. A Canadian single-center experience with 809 primary Profemur TL and Profemur Z stems at a mean followup of 5.7 years found four hips (0.5%) with titanium modular femoral neck fractures [14]. Silverton et al. [26] reported one fracture (0.7%) in a cohort of 152 hips. In the series published by Pour et al. [25] the main reason for revision of 107 Profemur Z stems was modular neck fracture, which occurred in 6% of the hips. To the best of our knowledge, the presented study is the largest published series on neck fractures of this particular bimodular stem design, which is still marketed (Table 3). Because fractures of the neck in our study are not limited only to long necks but occurred with short necks as well (0.14%), we believe that our results should caution the surgeon against using these stems in routine clinical practice.

CoCr material, time from implantation, longer neck length, male sex, and younger age were the factors independently associated with modular neck fracture in our series. In vitro testing have shown reduced abrasion, improved fretting resistance, and enhanced fatigue strength of more rigid CoCr alloy necks compared with titanium alloy ones [15]. Based on that, some manufacturers switched to CoCr-based alloys for modular neck production. Nevertheless, the first report of a CoCr modular femoral neck fracture was published in 2014 [22]. Recent studies have shown clear evidence of accelerated corrosion and fatigue behavior of the modular junction placed in an environment similar to the living tissue or mechanical conditions resembling functional biomechanics, calling for accurate test procedures to better predict in vivo implant failures [1, 8, 11, 17]. In a case series of modular CoCr neck corrosion failures with a titanium alloy stem, the authors recommended heightened awareness in all active female patients with modular neck stem junctions [21]. Contrary to these findings, male sex was found to be a risk factor for modular neck fracture in our study. Modular neck fractures were described in patients with higher weight or higher BMI in a number of reports [3, 15, 25, 33]. Contrary to these findings, BMI was not associated with neck fractures in our series. However, the average BMI in the patients in our series was relatively low (29 kg/m2).

Modular necks of the Profemur Z stem analyzed in our series fractured unacceptably often, especially in younger patients of male sex. Replacing the titanium alloy component with CoCr for the neck material actually worsened the problem. Because of different subtypes of femoral offset and CCD angles of modern fixed-neck stems, these present a better option for primary THA. We believe that stem-neck modularity has no role in routine primary hip arthroplasty until issues with corrosion-induced fractures are resolved. Further research of titanium-based alloys and design improvements for the manufacturing of bimodular stems are needed before these devices can be safely used, at least in patients with severely distorted anatomy. At present and for most patients, we believe, based on our findings, the risks outweigh the benefits, and we found several dozen patients who had revisions and complications that they would not have had if a different stem had been used in their hips.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrej Strahovnik MD, MSc, and Mrs Denia Savarin for providing statistical help.

Footnotes

One of the authors (SK) lists the following relevant financial activities outside of this work and/or any other relationships or activities that readers could perceive to have influenced, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, this manuscript: payment for lectures from DePuy Synthes (Raynham, MA, USA) and Zimmer Biomet (Warsaw, IN, USA) in an amount of less than USD 10,000.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at Valdoltra Orthopaedic Hospital, Ankaran, Slovenia; the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia; the Department of Orthopaedics, General Hospital Celje, Celje, Slovenia; and the Department of Orthopaedics, University Medical Centre Maribor, Maribor, Slovenia.

References

- 1.Aljenaei F, Catelas I, Louati H, Beaulé PE, Nganbe M. Effects of hip implant modular neck material and assembly method on fatigue life and distraction force: amterial and assembly effects on modular necks. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:2023–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibeck MJ, Cummins T, Carothers J, Junick DW, White RE. A Comparison of two implant systems in restoration of hip geometry in arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:443–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atwood SA, Patten EW, Bozic KJ, Pruitt LA, Ries MD. Corrosion-induced fracture of a double-modular hip prosthesis: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1522–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Orthopaedic Association. The Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR). 2018. Available at: https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- 5.Colas S, Allalou A, Poichotte A, Piriou P, Dray-Spira R, Zureik M. Exchangeable femoral neck (dual-modular) THA prostheses have poorer survivorship than other designs: a nationwide cohort of 324,108 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:2046–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collet T, Atanasiu J-P, de Cussac J-B, Oufroukhi K, Bothorel H, Saffarini M, Badatcheff F. Midterm outcomes of titanium modular femoral necks in total hip arthroplasty. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:395–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox D. Regression models in life-tables. J Roy Statist Soc Series. 1972;34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding HH, Fridrici V, Bouvard G, Geringer J, Kapsa P. Influence of calf serum on fretting behaviors of Ti–6Al–4V and diamond-like carbon coating for neck adapter–femoral stem contact. Tribol Lett. 2018;66 Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11249-018-1069-z. Accessed August 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA. Class 1 device recall Profemur Plus CoCr Modular Neck PHAC1254. Class 1 Device Recall. 2015. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfRES/res.cfm?id=139368. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- 10.Fitch DA, Ancarani C, Bordini B. Long-term survivorship and complication rate comparison of a cementless modular stem and cementless fixed neck stems for primary total hip replacement. Int Orthop. 2015;39:1827–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleck C, Eifler D. Corrosion, fatigue and corrosion fatigue behaviour of metal implant materials, especially titanium alloys. Int J Fatigue. 2010;32:929–935. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fokter SK, Levašič V, Kovač S. The innovation trap: modular neck in total hip arthroplasty. Zdrav Vestn. 2017;86:115–126. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fokter SK, Rudolf R, Moličnik A. Titanium alloy femoral neck fracture—clinical and metallurgical analysis in 6 cases. Acta Orthop. 2016;87:197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gofton WT, Illical EM, Feibel RJ, Kim PR, Beaulé PE. A single-center experience with a titanium modular neck total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2450–2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grupp TM, Weik T, Bloemer W, Knaebel H-P. Modular titanium alloy neck adapter failures in hip replacement-failure mode analysis and influence of implant material. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krawiec H, Vignal V, Schwarzenboeck E, Banas J. Role of plastic deformation and microstructure in the micro-electrochemical behaviour of Ti–6Al–4V in sodium chloride solution. Electrochim Acta. 2013;104:400–406. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levašič V, Pišot V, Milošev I. Arthroplasty register of the Valdoltra Orthopaedic Hospital and implant retrieval program. Zdrav Vestn. 2009;78:71–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massin P, Geais L, Astoin E, Simondi M, Lavaste F. The anatomic basis for the concept of lateralized femoral stems: a frontal plane radiographic study of the proximal femur. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsushita A, Nakashima Y, Fujii M, Sato T, Iwamoto Y. Modular necks improve the range of hip motion in cases with excessively anteverted or retroverted femurs in THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:3342–3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McTighe T, Brazil D. Modular necks and corrosion - review of five cases. Reconstr Rev. 2016;6:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mencière M-L, Amouyel T, Taviaux J, Bayle M, Laterza C, Mertl P. Fracture of the cobalt-chromium modular femoral neck component in total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100:565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelayo-de-Tomás JM, Rodrigo-Pérez JL, Novoa-Parra CD, Lizaur-Utrilla A, Morales-Suárez-Varela M, Blas-Dobón JA. Cementless modular neck stems: are they a safe option in primary total hip arthroplasty? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28:463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant test procedures. J R Statist Soc A. 1972;135:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pour AE, Borden R, Murayama T, Groll-Brown M, Blaha JD. High risk of failure with bimodular femoral components in THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:146–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverton CD, Jacobs JJ, Devitt JW, Cooper HJ. Midterm results of a femoral stem with a modular neck design: clinical outcomes and metal ion analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1768–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SURS. Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. 2018. Available at: https://www.stat.si/StatWeb/en/News/Index/6750. Accessed December 8, 2018.

- 28.Toni A, Giardina F, Guerra G, Sudanese A, Montalti M, Stea S, Bordini B. 3rd generation alumina-on-alumina in modular hip prosthesis: 13 to 18 years follow-up results. Hip Int. 2017;27:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traina F, Fine MD, Tassinari E, Sudanese A, Calderoni PP, Toni A. Modular neck prostheses in DDH patients: 11-year results. J Orthop Sci. 2011;16:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turley GA, Griffin DR, Williams MA. Effect of femoral neck modularity upon the prosthetic range of motion in total hip arthroplasty. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2014;52:685–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uchiyama K, Yamamoto T, Moriya M, Fukushima K, Minegishi Y, Takahira N, Takaso M. Early fracture of the modular neck of a MODULUS femoral stem. Arthroplast Today. 2017;3:93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson DA, Dunbar MJ, Amirault JD, Farhat Z. Early failure of a modular femoral neck total hip arthroplasty component: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1514–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright CG, Sporer S, Urban R, Jacobs J. Fracture of a modular femoral neck after total hip arthroplasty: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1518–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]