Abstract

Background:

With the increase in the use of soft-tissue fillers worldwide, there has been a rise in the serious adverse events such as vascular compromise and blindness. This article aims to review the role of fillers in causing blindness and the association between hyaluronic acid (HA) filler and blindness.

Methods:

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines were used to report this review.

Results:

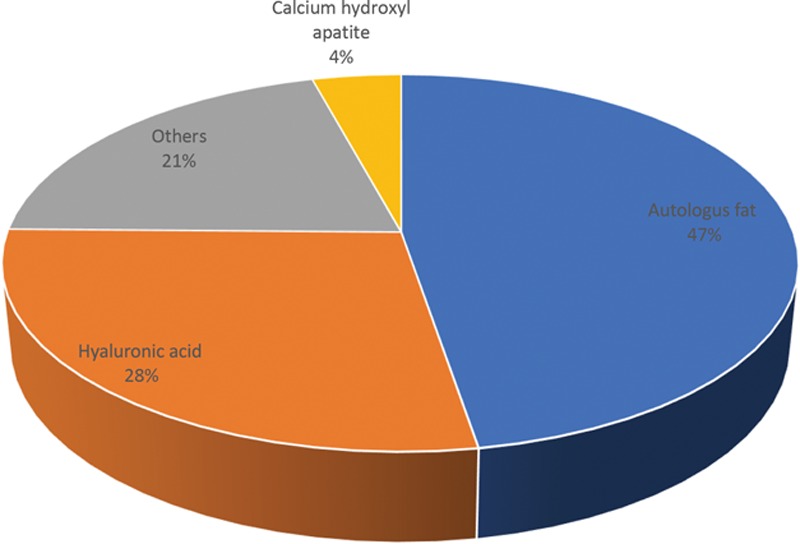

A total of 190 cases of blindness due to soft-tissue fillers were identified, of which 90 (47%) cases were attributed to autologous fat alone, and 53 (28%) cases were caused by HA. The rest of the cases were attributed to collagen, calcium hydroxylapatite, and other fillers.

Conclusions:

Autologous fat was the most common filler associated with blindness despite HA fillers being the most commonly used across the globe. However, the blindness caused by other soft-tissue fillers like collagen and calcium hydroxylapatite was represented. It was also evident through the review that the treatment of HA-related blindness was likely to have better outcomes compared with other fillers due to hyaluronidase use.

INTRODUCTION

“Beauty” is a universal phenomenon that transcends geographical boundaries and cultures. Its occurrence or attainment influences self-confidence, improves psychological standing, and elevates personal and professional capabilities.1 Minimally invasive cosmetic procedures have increased relative to other aspects of cosmetic surgery due to its advantages of achieving a subtle natural appearance, restoring natural contour, reducing morbidity, requiring less downtime posttreatment, and the easy availability of these procedures.2

A plethora of soft-tissue fillers for facial aesthetic correction ranging from autologous fat, polymethylmethacrylate, calcium hydroxylapatite, poly-L-Lactic acid, polycaprolactone, and hyaluronic acid (HA) are available. Of these, HA is the most widely used filler (over 2 million) with the longevity of approximately 6–24 months depending on the molecular size, a method of cross-linking, and the region of injection.3 Fillers have been traditionally associated with mild and transient adverse events such as bruising, swelling, infection, and surface irregularities. However, with the increased use of fillers worldwide, more serious and permanent adverse events such as vascular compromise and blindness are on the rise.4 Vision loss is a rare adverse event but catastrophic to both patient and the physician.5

With the increase in the availability of the soft-tissue fillers, number of aesthetic practitioners, and demand for aesthetic procedures globally, the usage of fillers is expected to rise. It is imperative that aesthetic physicians have a firm knowledge of the vascular anatomy and understand potential complications, critical prevention, and management strategies.6,7

The present systematic review has been conducted to elucidate the occurrence of blindness with various soft-tissue fillers, the association between HA filler and blindness, and to review factors influencing the development of blindness. We aim to fill in the gap between the existing practice and knowledge about the adverse effect of blindness in relation to the use of soft-tissue fillers, so that clinicians can make evidence-based decisions.

METHODS

A systematic review of the published literature was conducted to assess the association of blindness with the soft-tissue filler injections. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines were used to report this review.8

Criteria for Considering Studies for the Review

Inclusion Criteria

The relevant articles that met the following criteria were selected.

Original articles and expert’s opinions published between January 2000 and September 2018 that investigated or discussed the role of soft-tissue fillers (or HA fillers, autologous fat, calcium hydroxylapatite or collagen, and others) in causing blindness.

Articles published in English Language only.

Exclusion Criteria

We excluded the following articles:

in which patients underwent surgical correction,

where injections of nonfiller materials (corticosteroids) were given,

where vascular complications other than blindness were discussed, and

posters/abstracts and studies on animal models.

Literature Search

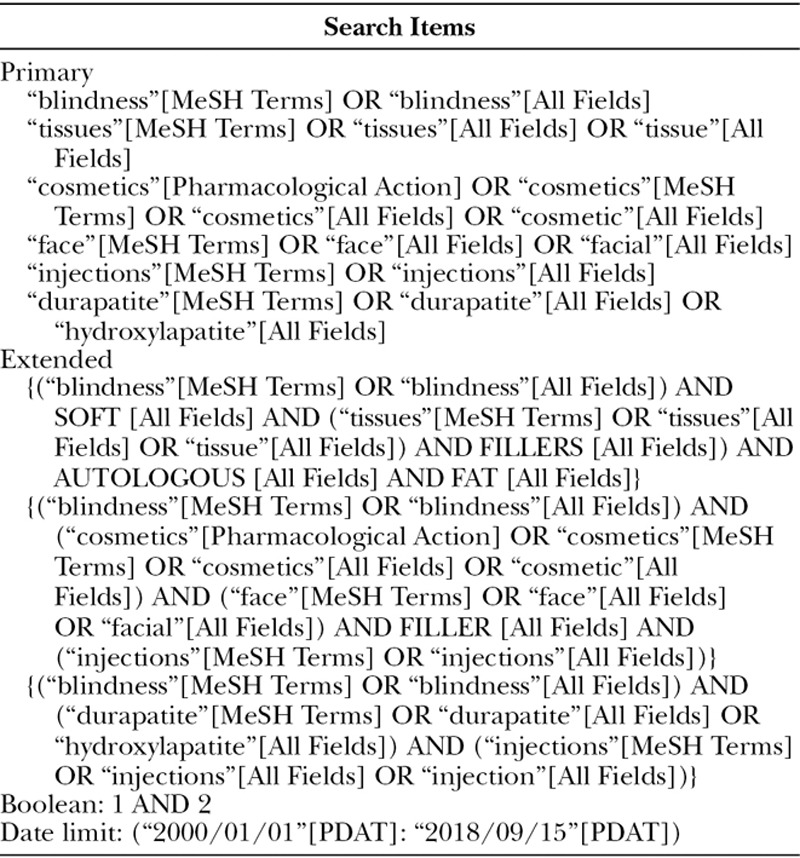

The goal was to analyze all the published literature comprising original research, clinical trials, case reports, retrospective and prospective case studies, systematic reviews and meta-analysis. A search of the computerized bibliographic database: Medline, Cochrane, PubMed, Google, and Google Scholar were performed. The MeSH terms used in the search were: tissues; blindness; injections; face; cosmetics; HA, including additional search terms like blindness; soft; filler; fat; hyaluronic; and autologous fat. The favorite key phrases used for search included cosmetic injections; facial aesthetics; soft-tissue fillers; hyaluronic acid; soft-tissue fillers; injectables; blindness; vision loss; acquired blindness; autologous fat; collagen; and calcium hydroxylapatite. In a backward chronological search, the bibliographies of all relevant articles were checked for citations that could not be identified in our primary search. The primary search strategy is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main Search Strategy for PubMed

Screening

Titles and abstracts from the electronic search were screened, and full-text manuscripts meeting the selection criteria were obtained. Crucial information from all the articles such as study design, number of cases, adverse effects, the filler used, mechanism, treatment, or any other pertinent data was extracted. Two investigators (V.C. and P.S.B.) independently extracted data from eligible studies, and any differences were resolved through discussion and consensus between the authors. When a consensus was not reached, arbitration was done by the third author (E.R.).

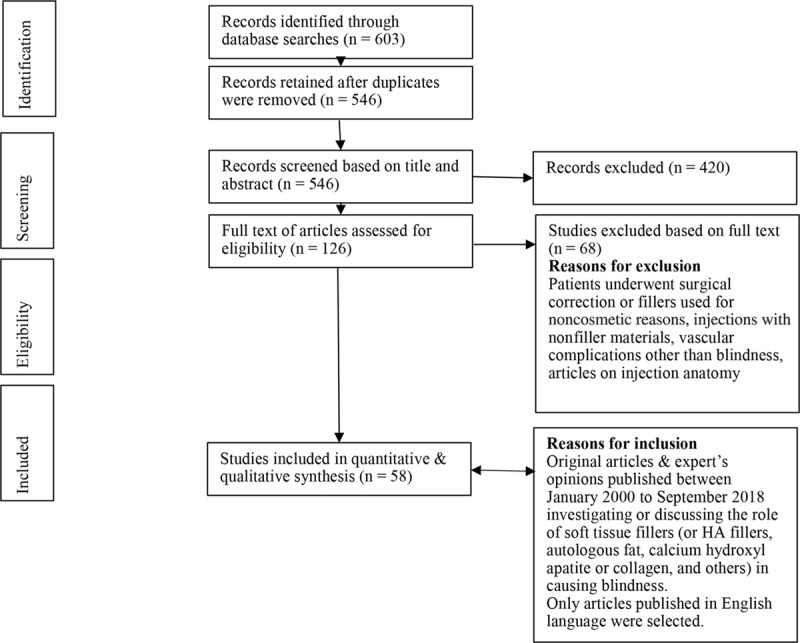

The selected articles were then qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed by the investigators. The process of screening, selection, and the inclusion of eligible articles and reasons for exclusion were displayed in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for study screening, selection, and inclusion.

Data Items, Extraction, and Synthesis

The data were retrieved by reading the entire article. Papers were reported in a table with the following fields: record number, the name of the author(s), publication year, article title, and journal. Relevant data from eligible full texts were extracted by 2 authors (V.C. and P.S.B.) using prestructured data abstraction sheets. Two data abstraction sheets were predesigned to extract available data on the author, year of case reporting with a number of cases, geographic region, type of soft-tissue filler used, the anatomical area of injection, and any ocular complication and recovery. The disagreements were resolved as detailed above.

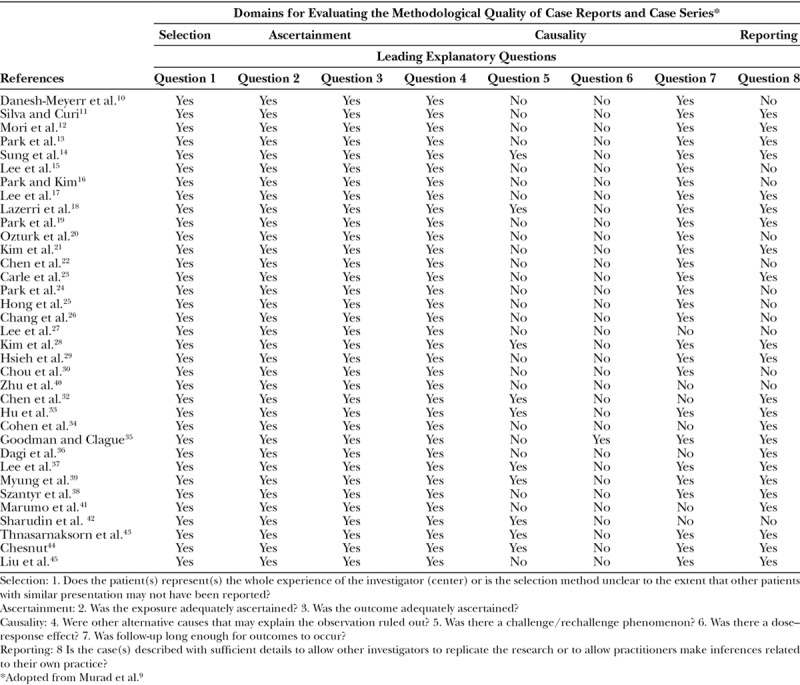

Assessment of Methodological Quality

A validated tool for the determination of the methodological quality of the case reports and case series proposed by Murad et al9 based on the previous criteria from Pierson, Bradford Hills, and Newcastle-Ottawa scale modifications was used. Each case study or series was evaluated under 4 domains (selection, ascertainment, causality, and reporting) that are summarized in Table 1. This resulted in 8 leading exploratory questions with a binary response (yes/no), whether the item was suggestive of bias or not. No disagreements were found between the reviewers.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Due to the small number and evident heterogeneity among the included studies reporting on a wide variety of risk factors associated with ocular complication, the findings herein were presented using tables and narrative summaries.

RESULTS

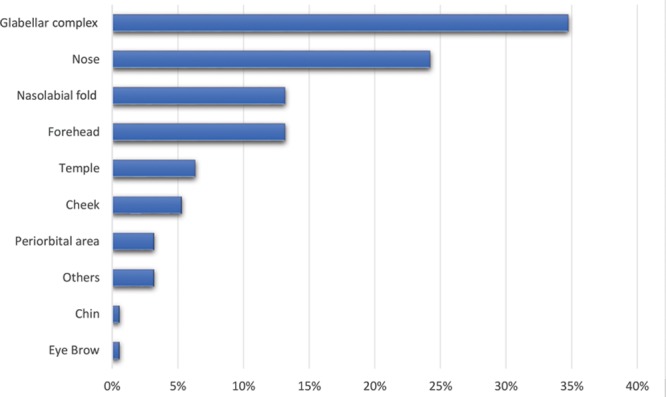

A total of 190 cases of filler-induced blindness were identified in the present study. The maximum cases of filler-induced blindness or other ocular disturbances were attributed to autologous fat injections (90 cases; 47%). The second most prominent cause of filler-induced blindness was due to HA (53 cases; 28%), whereas rest of the cases were attributed to collagen, calcium hydroxylapatite, and other fillers. However, it is interesting to note that 11 HA-related blindness cases had significant improvement in visual acuity and 6 cases of complete vision restoration when treated with hyaluronidase. The visual outcome was not good in any other filler-induced blindness. It is also notable that 8 cases of calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA)–induced blindness were reported between 2014 and 2018. Figures 2 and 3 depict the number of blindness cases caused by various soft-tissue fillers and the percentage of reported blindness according to the injection site.

Fig. 2.

Number of blindness cases due to various soft-tissue fillers.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of reported filler-associated blindness according to the injection site.

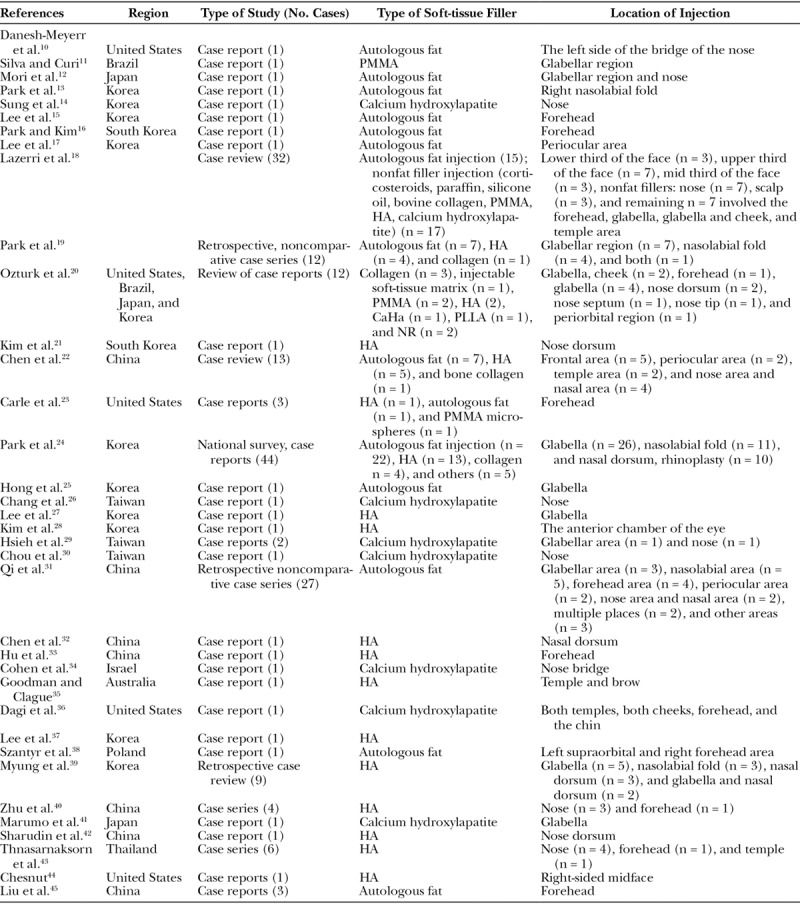

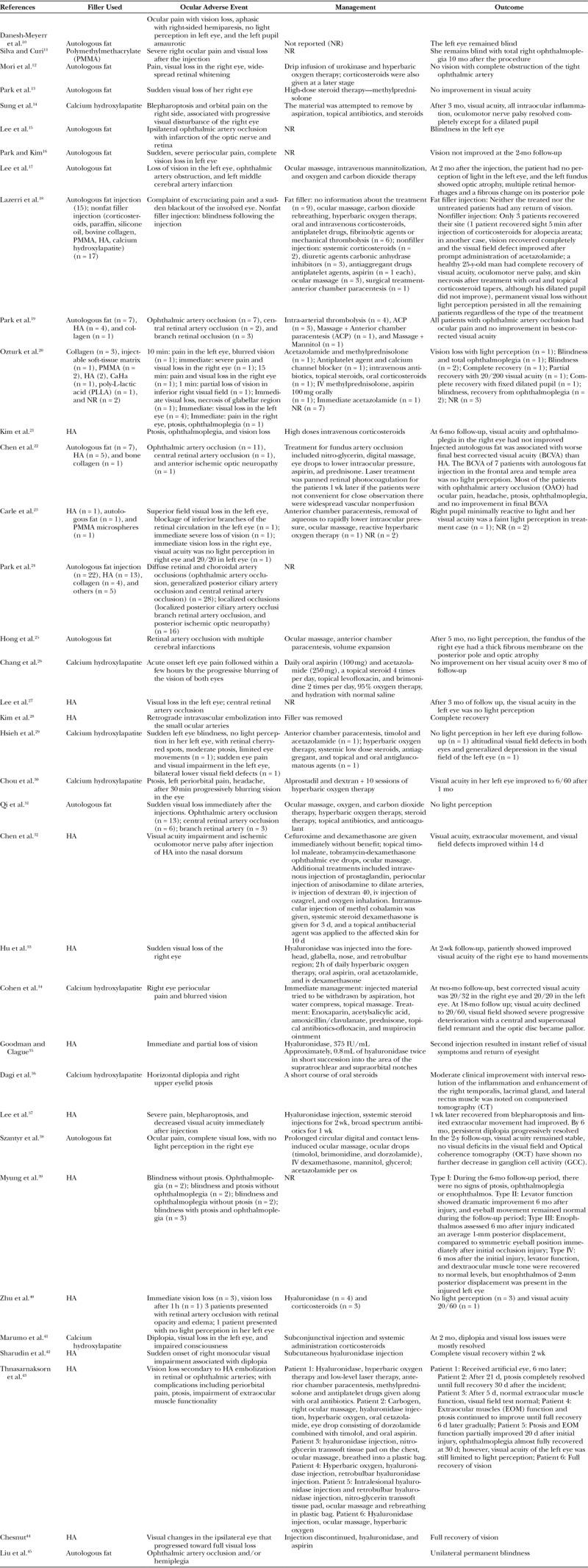

Characteristics of the studies included in the review (Table 3) and a summary of different cases of blindness between the January 2000 and September 2018 based on the type of filler used, ensuing adverse event, management, and its outcome is presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Studies Included

Table 4.

Brief Description of the Ocular Adverse Event, Management, and Outcome Associated with Soft-Tissue Fillers

Table 2.

Qualitative Assessment of the Included Studies

DISCUSSION

Blindness Associated with Soft-tissue Fillers

Vascular occlusion is a rare but severe and dreaded complication of soft-tissue fillers. It occurs because of inadvertent injection of the filler material in a blood vessel. This intravascular injection of fillers may lead to complications such as tissue ischemia and loss, blindness, pulmonary embolization,46 and even stroke.47 In a recent study published by Povolotskiy et al48 investigating the adverse events arising with various aesthetic fillers, vascular complications were cited to be among some of the commonly occurring complications. This study comprised 5,024 cases, out of which vascular complications were observed in 590 cases. Even though blindness caused by soft-tissue fillers is an infrequent event, it is a matter of great concern owing to its distressing consequences.49 The causative agents that may lead to blindness include autologous fat, HA, collagen, poly-L-Lactic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, and even corticosteroid suspensions.50 Vision loss manifests as an immediate complication of facial filler injection with other associated signs and symptoms depending on the location of vascular occlusion.51

Rzany and DeLorenzi52 reported in a small retrospective study that vascular occlusions, such as of ophthalmic and/or retinal artery resulting in blindness, are apparently more common and more severe in non-HA fillers. A review by Beleznay et al2 demonstrated that the incidence of vascular occlusion following an injection of a filler is estimated to be approximately 3–1,000 in case of calcium hydroxylapatite, whereas 3–9 per 10,000 for HA preparations. It was also suggested that vascular complications and sequelae were more severe with non-HA fillers such as calcium hydroxylapatite and polymethylmethacrylate.52

Beleznay et al2 showed that almost 47.9% of cases of blindness were caused by autologous fat, whereas HA fillers were responsible for 23.5% of the cases which are consistent with the present finding. Autologous fat, the most viscous soft-tissue filler had the highest risk of diffuse occlusion in the ophthalmic artery and was also associated with poor prognosis.50

In a retrospective study conducted between January 1, 2008 and August 31, 2014, Kim et al53 also observed that the prevalence of diffuse occlusion of ophthalmic artery and its branches is less in HA-injected patients compared with autologous fat–injected group. This could be attributed to the difference in the particle sizes of the 2 fillers. Autologous fat has a variable particle size, whereas HA particles are approximately 400 μm in size. Hyaluronic acid fillers are more likely to block the central retinal artery (approximately 160 μm in size) or its smaller branches and fat more likely the ophthalmic artery (2 mm in diameter) due to the particle size and the amount of filler injected per injection site.53 Chen et al22 while studying fundus artery occlusion also found that the prognosis was found to be much worser in autologous fat than in HA.

Previous studies have also reported that injections with autologous fat are associated with a higher diffuse occlusion rate, resulting in a much worse visual prognosis and more frequent cerebral infarctions compared with HA.24,53

The Mechanism for HA-induced Blindness versus Blindness Induced by Other Fillers

Currently, it is thought that an accidental injection of fillers into the blood vessel can lead to the formation of tissue filler emboli. Various authors have suggested that the mechanism of this is most likely through initially retrograde flow against the prevailing blood pressure to a point at or past the retinal branches. Consequent release of the syringe pressure allows the usual blood pressure to reestablish the antegrade blood flow carrying forward these emboli allowing them to enter the ophthalmic artery circulation. This embolus is responsible for retinal ischemic necrosis. The ophthalmic artery branches with cutaneous innervation (supplying the glabella, nose periorbital zone, and forehead) probably carry the greatest risk, but anastomoses between facial artery and branches of the ophthalmic artery have been shown in cadaveric studies.49

A cadaveric study published in June 2018 has suggested that retrograde HA filler emboli to the ophthalmic artery may be a result of the cannulation of the supratrochlear artery, primarily due to its superficial location surrounded by rich vasculature and a variable anatomy.54 Sufan et al55 published an article in 2017 which showed that in the glabellar region, the deep injection on the periosteum will be at a risk of entering the supratrochlear artery and supraorbital artery, whereas, in nasal dorsum and nasolabial folds, the subsuperficial musculoaponeurotic system layer injection has the possibility to enter the dorsal nasal artery, angular artery, and facial artery.

It has also been suggested that the volume of the filler injected, and the pressure of injection can impact the outcome of blindness by influencing the retrograde flow of the filler into the ophthalmic circulation. The amount of soft-tissue filler injected varies according to the type of filler used, for example, autologous fat is typically injected in larger volumes compared with HA fillers.56

Even though both fat and HA fillers may cause vision loss, the occlusion of the ophthalmic circulation vessels would vary due to the particle size and the amount of filler injected per injection site. This could explain why the case series by Park et al. showed that autologous fat was associated with a higher diffuse occlusion with worse visual prognosis and a higher incidence of concomitant cerebral infarction.13,23

The speed and pressure of injection have also been proposed to influence the flow of the filler after its inadvertent injection into the vessel. This has a direct impact on the speed and pressure of injection as the viscosity of the filler influences the extrusion force (injection pressure) used by the injector that will then determine the speed and pressure of injection finally affecting the flow of the filler within the vessel. A highly viscous filler (like fat) will require a higher extrusion force compared with a filler that is less viscous.

Another factor influencing the extrusion force is the size of the syringe and gauge of the needle/cannula which is determined by choice of the soft-tissue filler used. Typically, autologous fat is injected using large gauge needles and an increased force used to inject it would be easier to produce57 increasing the likelihood of a large bolus if intravascular penetration occurs.

Interestingly, the propensity of soft-tissue fillers in activating clotting mechanism also influences their effect. The noninflammatory fillers may purely cause a mechanical obstruction when placed within the blood vessel. However, others can activate an intravascular inflammatory reaction over and above the mechanical blockage accentuating the obstruction and consequently cause ischemia and blindness. In fact, it has been shown that HA may have heparin-like activity as opposed to collagens clot promoting action.58

Can Blindness due to HA Injection Be Prevented or Treated?

It has been seen that hyaluronidase, an enzyme that degrades HA, may improve outcomes following an accidental intravascular HA filler injection. A review conducted by Carruthers et al59 showed that when hyaluronidase was injected next to a blood vessel clogged with HA, it catabolized the HA without needing to canalize the affected artery. It is also suggested that in the case of retinal artery embolization with the HA product, retrobulbar injection of a large volume of hyaluronidase might well be the single most effective option to dissolve the intraorbital intravascular hyaluronan in a time-sensitive manner.59

In 2018, a case reported by Sharudin et al42 showed a complete visual recovery of posterior ischemic optic neuropathy with ophthalmoplegia caused by HA filler injection. It has been suggested that in the case of embolism caused by HA, hyaluronidase given within the window period of 60–90 min has a strong chance of dissolving HA embolism.42 Another series of 6 cases of vision loss caused by HA filler injection showed improved visual acuity or complete reversal in 4 of the cases. The authors suggested that early supratrochlear/supraorbital hyaluronidase injection, ocular massage, and rebreathing into a plastic bag can be safe, uncomplicated and effective methods to enable restoration of the retinal circulation, and reverse vision loss.43 Chesnut44 also reported a case of recovery of HA filler visual loss after using retrobulbar hyaluronidase injection, although Zhu et al40 reported no recovery of vision loss in all 4 reported cases despite the use of retrobulbar hyaluronidase; albeit, these cases were all injected after 4 hours of occlusion and did not fall in the window of 60–90 min of perceived best opportunity for visual slavage.

Although consensus recommendations for the avoidance and management of complications from HA fillers including blindness are available,60 there is no evidence that following the currently available guidelines would reverse the vision loss necessitating a need for a specific protocol that can be followed to universally reverse all cases of blindness secondary to HA fillers. However, it is worthy to note that this possibility of reversal of iatrogenic blindness is likely to be possible with HA fillers and not others like autologous fat, collagen, or calcium hydroxylapatite.

Inconsistencies in recommendations for safer injection technique and lack of evidence to correlate the impact of injection technique on the occurrence of blindness necessitate the need for exploratory research. Better reporting of cases of blindness through a registry with details of the injection technique provided, including type of filler, use of needle or cannula (with size), use of local anesthesia, etc., can help to better understand the mechanism for the causation of blindness retrospectively so that preventive measures can be put in place. Additionally, the effect of different fillers (including the various brands of HA fillers available worldwide) on the vessel wall can be studied in vitro to establish the safety profile of the differently available fillers.

LIMITATIONS

This systematic review has many limitations. First, there was no uniformity in presenting the cases, and many important parameters or variables were not reported. Second, as with any case reports, the information regarding the rate, ratios, incidences, or prevalence cannot be generated because they are not representative of the population. Last, as with descriptive studies, one cannot deduce the cause–effect relationship; hence, the findings cannot be generalized.

CONCLUSIONS

Even though rare, vision loss due to HA injection is a disastrous event. When vision loss occurs, with limited time for restoration, early recognition and prompt treatment are crucial. There is no gold standard for the treatment of vision loss, and even though there have been consensus recommendations, no specific guidelines are available which have been universally successful in reversing this complication.

HA-based fillers appear to be relatively safer soft-tissue fillers, although it will be prudent to say that profound medical, anatomical, and product knowledge are required to minimize the occurrence of grave adverse reactions such as blindness associated with their use.

Footnotes

Published online 2 April 2019.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patzer GL. Improving self-esteem by improving physical attractiveness. J Esthet Dent. 1997;9:44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beleznay K, Carruthers JD, Humphrey S, et al. Avoiding and treating blindness from fillers: a review of the world literature. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haneke E. Managing complications of fillers: rare and not-so-rare. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferneini EM, Ferneini AM. An overview of vascular adverse events associated with facial soft tissue fillers: recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74:1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humzah MD, Ataullah S, Chiang C, et al. The treatment of hyaluronic acid aesthetic interventional induced visual loss (AIIVL): a consensus on practical guidance. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar N, Rahman E. Effectiveness of teaching facial anatomy through cadaver dissection on aesthetic physicians’ knowledge. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar N, Swift A, Rahman E. Development of “core syllabus” for facial anatomy teaching to aesthetic physicians: a Delphi consensus. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6:e1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. ; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, et al. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danesh-Meyerr HV, Savino PJ, Sergott RC. Ocular and cerebral ischemia following facial injection of autologus fat. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2001;119:777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva MT, Curi AL. Blindness and total ophthalmoplegia after aesthetic polymethylmethacrylate injection: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62:873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori K, Ohta K, Nagano S, et al. A case of ophthalmic artery obstruction following autologous fat injection in the glabellar area. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;111:22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park SH, Sun HJ, Choi KS. Sudden unilateral visual loss after autologous fat injection into the nasolabial fold. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2:679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung MS, Kim HG, Woo KI, et al. Blindness ischemia and ischemic oculomotor nerve palsy after vascular embolization of injectable calcium hydroxylapatite filler. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee YJ, Kim HJ, Choi KD, et al. MRI restricted diffusion in optic nerve infarction after autologous fat transplantation. J Neuroophthalmol. 2010;30:216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park Y-H, Kim KS. Blindness after fat injections. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CM, Hong IH, Park SP. Ophthalmic artery obstruction and cerebral infarction following periocular injection of autologous fat. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011;25:358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Figus M, et al. Blindness following cosmetic injections of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SW, Woo SJ, Park KH, et al. Iatrogenic retinal artery occlusion caused by cosmetic facial filler injections. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozturk CN, Li Y, Tung R, et al. Complications following injection of soft-tissue fillers. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SN, Byun DS, Park JH, et al. Panophthalmoplegia and vision loss after cosmetic nasal dorsum injection. J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21:678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Wang W, Li J, et al. Fundus artery occlusion caused by cosmetic facial injections. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127:1434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carle MV, Roe R, Novack R, et al. Cosmetic facial fillers and severe vision loss. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park KH, Kim YK, Woo SJ, et al. ; Korean Retina Society. Iatrogenic occlusion of the ophthalmic artery after cosmetic facial filler injections: a national survey by the Korean Retina Society. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong DK, Seo YJ, Lee JH, et al. Sudden visual loss and multiple cerebral infarction after autologous fat injection into the glabella. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang TY, Pan SC, Huang YH, et al. Blindness after calcium hydroxylapatite injection at nose. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee WS, Yoon WT, Choi YJ, et al. Multiple cerebral infarctions with neurological symptoms and ophthalmic artery occlusion after filler injection. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2015;56:285. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DY, Eom JS, Kim JY. Temporary blindness after an anterior chamber cosmetic filler injection. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015;39:428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh YH, Lin CW, Huang JS, et al. Severe ocular complications following facial calcium hydroxylapatite injections: Two case reports. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2015;5:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chou CC, Chen HH, Tsai YY, et al. Choroid vascular occlusion and ischemic optic neuropathy after facial calcium hydroxyapatite injection—a case report. BMC Surg. 2015;15:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qi X, Zhou J, Ma L, et al. Analysis of artery occlusion caused by facial autologous fat injections. Dig Med. 2015;1:39. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen W, Wu L, Jian X-L, et al. Retinal branch artery embolization following hyaluronic acid injection: a case report. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:NP21924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu XZ, Hu JY, Wu PS, et al. Posterior ciliary artery occlusion caused by hyaluronic acid injections into the forehead: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen E, Yatziv Y, Leibovitch I, et al. A case report of ophthalmic artery emboli secondary to calcium hydroxylapatite filler injection for nose augmentation- long-term outcome. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodman GJ, Clague MD. A rethink on hyaluronidase injection, intraarterial injection, and blindness: is there another option for treatment of retinal artery embolism caused by intraarterial injection of hyaluronic acid? Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dagi Glass LR, Choi CJ, Lee NG. Orbital complication following calcium hydroxylapatite filler injection. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33: S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JI, Kang SJ, Sun H. Skin necrosis with oculomotor nerve palsy due to a hyaluronic acid filler injection. Arch Plast Surg. 2017;44:340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szantyr A, Orski M, Marchewka I, et al. Ocular complications following autologous fat injections into facial area: case report of a recovery from visual loss after ophthalmic artery occlusion and a review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myung Y, Yim S, Jeong JH, et al. The classification and prognosis of periocular complications related to blindness following cosmetic filler injection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu GZ, Sun ZS, Liao WX, et al. Efficacy of retrobulbar hyaluronidase injection for vision loss resulting from hyaluronic acid filler embolization. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;38:12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marumo Y, Hiraoka M, Hashimoto M, et al. Visual impairment by multiple vascular embolization with hydroxyapatite particles. Orbit. 2018;37:165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharudin SN, Ismail MF, Mohamad NF, et al. Complete recovery of filler-induced visual loss following subcutaneous hyaluronidase injection. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2018; doi:10.1080/01658107.2018.1482358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thanasarnaksorn W, Cotofana S, Rudolph C, et al. Severe vision loss caused by cosmetic filler augmentation: case series with review of cause and therapy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chesnut C. Restoration of visual loss with retrobulbar hyaluronidase injection after hyaluronic acid filler. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu H, Chen D, Zhang J. Ophthalmic artery occlusion after forehead autologous fat injection. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2018;doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jang JG, Hong KS, Choi EY. A case of nonthrombotic pulmonary embolism after facial injection of hyaluronic Acid in an illegal cosmetic procedure. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2014;77:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferneini EM, Hapelas S, Watras J, et al. Surgeon’s guide to facial soft tissue filler injections: relevant anatomy and safety considerations. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 75: e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Povolotskiy R, Oleck NC, Hatzis CM, et al. Adverse events associated with aesthetic dermal fillers: 10-year retrospective study of FDA data. Am J Cosmet Surg. 2018;35:143. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng H, Qiu L, Liu Z, et al. Exploring the possibility of a retrograde embolism pathway from the facial artery to the ophthalmic artery system in vivo. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prado G, Rodríguez-Feliz J. Ocular pain and impending blindness during facial cosmetic injections: is your office prepared? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li B, Allen LH, Sheidow TG. Vision loss and vascular compromise with facial and periocular injections. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015;50:e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rzany B, DeLorenzi C. Understanding, Avoiding, and managing severe filler complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5 Suppl):196S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim YK, Jung C, Woo SJ, et al. Cerebral angiographic findings of cosmetic facial filler-related ophthalmic and retinal artery occlusion. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cho KH, Pozza ED, Toth G, et al. Pathophysiology study of filler-induced blindness. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39:96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sufan W, Lei P, Hua W, et al. Anatomic study of ophthalmic artery embolism following cosmetic injection. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28:1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim A, Kim SH, Kim HJ, et al. Ophthalmoplegia as a complication of cosmetic facial filler injection. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:e377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pierre S, Liew S, Bernardin A. Basics of dermal filler rheology. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(Suppl 1):S120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sorensen EP, Urman C. Cosmetic complications: rare and serious events following botulinum toxin and soft tissue filler administration. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carruthers JD, Fagien S, Rohrich RJ, et al. Blindness caused by cosmetic filler injection: a review of cause and therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Signorini M, Liew S, Sundaram H, et al. ; Global Aesthetics Consensus Group. Global aesthetics consensus: avoidance and management of complications from hyaluronic acid fillers-evidence- and opinion-based review and consensus recommendations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:961e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]